The Civil War was accompanied by frightful pogroms in the Right-Bank Ukraine, the worst violence the Jews had suffered since the Cossack Hetman Bohdan Chmielnicki had ruled this region nearly three centuries earlier.

At the outbreak of World War I, almost two-thirds of the world’s Jews lived in the Russian Empire. Their status was exceedingly precarious. Tsarist legislation compelled all but a handful of rich or educated Jews to reside in the Pale of Settlement, an area carved out of the western Ukraine, Belorussia, Lithuania, and Poland, where they had lived when Russia acquired those areas during the partitions of Poland. In this territory, as members of the burgher estate, they had to reside in the towns and make a living by trade and artisanship. There were quotas on Jewish admissions to secondary schools and universities. Jews were entirely excluded—the only ethnic group subject to this disability—from the civil service and officer ranks in the armed forces. They were treated as a pariah caste, a status that was increasingly anachronistic and contrary to the general trend of late Imperial Russia toward equal citizenship. Most seriously affected by these disabilities were secular Jews, who no longer fitted into traditional Jewish society and yet found most avenues of advancement in the dominant Christian society blocked.

In the early twentieth century, enlightened Russian bureaucrats urged that Jews be granted at least partial if not full equality.222 They argued that Russia’s medieval laws embarrassed her abroad and made it more difficult to secure loans from international banks, in which Jews played an important role. Furthermore, the artificial obstacles to their education and career opportunities drove Jewish youths into revolutionary activity. But this advice was not acted upon, in part because of the opposition of the Ministry of the Interior, which feared Jewish economic and political penetration into the villages, and in part because of the anti-Semitism of Nicholas II and his entourage.

The Pale of Settlement died a natural death during World War I, when several hundred thousand Jews moved into the interior of Russia, some expelled from their homes, others escaped from the front zone. Half a million Jews served in the Imperial army during World War I, but only as rank-and-file soldiers—the first Jewish officers, no more than a few dozen, were commissioned by the Provisional Government,223 which formally abolished the Pale and eliminated the remaining Jewish disabilities. Jews kept on dispersing in the interior during and after the Civil War. In 1923, the Jewish population inhabiting Great Russia had grown to 533,000, from 153,000 in 1897. At the same time, in what had been the Pale, Jews moved from the small towns, where two-thirds of them had resided before the Revolution, to the larger cities.224 After 1917, Jews, for the first time in Russian history, made an appearance as government officials. Thus it happened that with the Revolution Jews suddenly showed up in parts of the country where they had never been seen before, and in capacities they had never previously exercised.

It was a fatal conjunction: for most Russians the appearance of Jews coincided with the miseries of Communism and so was identified with them. In the words of a Jewish contemporary:

Previously, Russians have never seen a Jew in a position of authority: neither as governor, nor as policeman, nor even as postal employee. Even then, there were, of course, better times and worse times, but the Russian people had lived, worked, and disposed of the fruits of their labor, the Russian nation grew and enriched itself, the Russian name was grand and awe-inspiring. Now the Jew is on every corner and on all rungs of power. The Russian sees him as head of the ancient capital, Moscow, and in charge of the capital on the Neva, and in command of the Red Army, that most perfect mechanism of [national] self-destruction. He sees the Prospect of St. Vladimir bear the glorious name of Nakhimson, the historic Liteinyi Prospect renamed the Prospect of Volodarskii, and Pavlovsk become Slutsk. The Russian now sees the Jew as judge and executioner. He meets Jews at every step—not Communists, but people as hapless as himself, yet issuing orders, working for the Soviet regime; and this regime, after all, is everywhere, one cannot escape it. And this regime, had it emerged from the lowest depths of hell, could not be more malevolent or brazen. Is it any wonder, then, that the Russian, comparing the past with the present, concludes that the present regime is Jewish and therefore so diabolical?225

The consequence was the eruption of a virulent anti-Semitism, first in Russia, then abroad. Just as socialism was the ideology of the intelligentsia, and nationalism that of the old civil and military Establishment, so Judeophobia became the ideology of the masses. At the conclusion of the Civil War, a Russian publicist observed that “Hatred of Jews is one of the most prominent features of contemporary Russian life; possibly even the most prominent. Jews are hated everywhere, in the north, in the south, in the east and in the west. They are detested by all social orders, by all political parties, by all nationalities and by persons of all ages.”* By late 1919, even the liberal Kadets were afflicted with the poison.226

The immediate cause of this psychotic hatred, symptomatic of a society in moral and psychic crisis, was the sense that whereas everybody else had lost from the Revolution, the Jews, and they alone, had benefited from it. This perception led to the conclusion that they had masterminded the Revolution. The view received spurious theoretical justification from the so-called Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a forgery fostered, and perhaps partly created, by the tsarist police; having attracted scant attention on publication in 1902, the Protocols now gained worldwide notoriety. Its argument that Jews were secretly conspiring to conquer and subjugate mankind appeared prophetic in the light of events in Russia. The connection between Jewry and Communism, drawn in the aftermath of the Revolution and exported from Russia to Weimar Germany, was instantly assimilated by Hitler and made into a cardinal tenet of the Nazi movement.

The Bolsheviks did not tolerate on their territory overt manifestations of anti-Semitism, least of all pogroms, for they well realized that anti-Semitism had become a cover for anti-Communism.227 But for the same reason they did not go out of their way to publicize anti-Semitic excesses on the White side, so as not to play into the hands of those who accused their government of serving “Jewish” interests. During the 1919 pogroms in the Ukraine, apart from a few perfunctory protests, Moscow maintained a prudent silence, apparently afraid to encourage pro-White sentiments among its population.*

The paradox inherent in this situation was that although they were widely perceived as working for the benefit of their own people, Bolsheviks of Jewish origin not only did not think of themselves as Jews but resented being regarded as such. When, under tsarism, for conspiratorial reasons they adopted aliases, they invariably chose Russian names, never Jewish ones. They subscribed to Marx’s view that the Jews were not a nation but a social caste of a very pernicious and exploitative kind. They desired that Jews assimilate as rapidly as possible, and believed that this would happen as soon as they were compelled to engage in “productive” work. In the 1920s the Soviet regime would use Jewish Bolsheviks and members of the Jewish Socialist Bund to destroy organized Jewish life in Russia.

The reason for this apostasy lay in the fact that a Jew who, for whatever reason, wished to be rid of his Jewishness had only two choices open to him. One was to convert. But for a secular Jew, exchanging one religion for another was no solution. The alternative was to join the nation of the nationless, the radical intelligentsia, who constituted a cosmopolitan community indifferent to ethnic and religious origins and committed to the ideas of freedom and equality:

Bolshevism attracted marginal Jews, poised between two worlds—the Jewish and the Gentile—who created a new homeland for themselves, a community of ideologists bent on remaking the world in their own image. These Jews quite deliberately and consciously broke with the restrictive social, religious, and cultural life of the Jews in the Pale of Settlement and attacked the secular culture of Jewish socialists and Zionists. Having abandoned their own origins and identity, yet not finding, or sharing, or being fully admitted to Russian life (except in the world of the party) the Jewish Bolsheviks found their ideological home in revolutionary universalism.228

Jews active in the ranks of Bolshevism and the other radical parties were for the major part semi-intellectuals who thanks to various “diplomas” won the right to live outside the Pale of Settlement: they broke with their own society without gaining acceptance to the Russian one,229 except that segment of it made up of people like themselves.

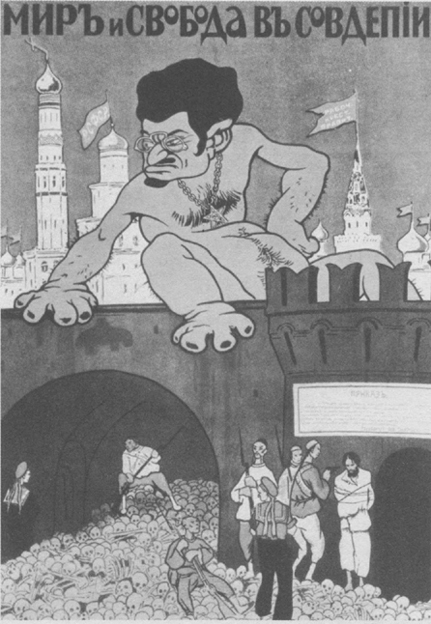

12. Anti-Trotsky White propaganda poster.

Trotsky—the satanic “Bronstein” of Russian anti-Semites—was deeply offended whenever anyone presumed to call him a Jew. When a visiting Jewish delegation appealed to him to help fellow Jews, he flew into a rage: “I am not a Jew but an internationalist.”230 He reacted similarly when requested by Rabbi Eisenstadt of Petrograd to allow special flour for Passover matzos, adding on this occasion that “he wanted to know no Jews.”231 At another time he said that the Jews interested him no more than the Bulgarians.232 According to one of his biographers, after 1917 Trotsky “shied away from Jewish matters” and “made light of the whole Jewish question.”233 Indeed, he made so light of it that when Jews were perishing by the thousands in pogroms, he seemed not to notice. He was in the Ukraine in August 1919, when it was the scene of some of the bloodiest massacres. A British scholar with access to the Soviet archives found that Trotsky had “received hundreds of reports about his own soldiers’ violence and looting of Jewish-Ukrainian settlements.”234 And yet neither in his public pronouncements nor in his confidential dispatches to Moscow did he refer to these atrocities: in the collection of his speeches and directives for the year 1919, the word “pogrom” does not even figure in the index.235 Indeed, at a meeting of the Politburo on April 18, 1919, he complained that there were too many Jews and Latvians in frontline Cheka units and in various office jobs, and recommended that they be more evenly distributed between the combat zone and the rear.236 In sum, during that year of slaughters he never once intervened by either word or deed for the people on whose behalf he was said to have acted. Nor does one find greater concern among Lenin’s other Jewish associates, or even among democratic socialists like Martov. In this respect the White generals, some of whom openly confessed to a dislike of Jews, have a better record than the Jewish Bolsheviks, in that, while they did next to nothing to prevent them, at least they condemned the pogroms and later expressed regrets over them.237

The desire of Jewish Bolsheviks to shed their Jewishness and disassociate themselves from their people sometimes attained grotesque dimensions, as in the case of Karl Radek, who, misquoting Heine to the effect that Jewishness was a “disease,” told a German friend that he wanted to “exterminate” (ausrotten) the Jews.*

The White movement in the first year of its existence was free of anti-Semitism, at any rate, in its overt manifestations. Jews served in the Volunteer Army and took part in its Ice March.238 In September 1918 Alekseev declared that anti-Semitism would not be tolerated in the Volunteer Army; the Jewish Kadet M. M. Vinaver affirmed in November 1918 that he had not encountered it in White ranks.239

All this changed in the winter of 1918–19. The hostility toward Jews that emerged in the Southern White Army at that time had three causes. One was the Red Terror, which it became customary to blame on Jews not only because of the conspicuous role they played in the Cheka, especially its provincial branches, but also because they were less victimized by it.† The second had to do with the consequence of the evacuation by German forces of Russia, following the Armistice in the West. In 1917–18 Russian anti-Bolsheviks persuaded themselves that Lenin’s regime was a German creation, without native roots, destined to fall the instant the Germans lost the war and withdrew from Russia. But the Germans withdrew and the Bolsheviks stayed on. This required a new scapegoat for the country’s misfortunes, which role the Jews filled eminently well for the reasons stated above. Finally, there was the murder of the Imperial family, particulars of which emerged during the winter of 1918–19. The killing was immediately blamed on Jews, who in fact played a secondary role in it; the fate of the ex-tsar was identified with the martyrdom of Christ and interpreted in the light of the Protocols as yet another step in the Jewish march to world mastery.

According to Denikin, when the White army entered the Ukraine, the region was in the grip of rabid anti-Semitism that affected all groups of the population, the intelligentsia included. The Southern Army, he concedes, did not “escape the general disease” and “besmirched” itself with Jewish pogroms as it advanced westward.240 Denikin now found himself under enormous pressure to purge the military and civil services of “traitorous” Jews. (This was not a problem for Kolchak, because few Jews lived in Siberia.) He tried but failed to stop the dismissals of Jewish officers demanded by Russians who refused to serve alongside them. His orders were ignored and he had to place Jews in reserve units. For the same reason Jews who either volunteered or were conscripted into the White Southern Army were formed into separate units.241 In 1919 it became common practice in areas occupied by the White army to require the removal of “Jews and Communists” from all positions of authority. In August 1919 in occupied Kiev, the Whites installed a municipal government from which the single Jew was dismissed on orders of the White general Dragomirov.242 Fearful of earning the reputation of a “Jew-lover,” Denikin rejected every appeal (including one from Vassili Maklakov, the Russian ambassador in Paris) to appoint a token Jew to his civil administration.243

As it neared Moscow, Denikin’s army became increasingly infected with hatred of Jews and lust for vengeance for the miseries they had allegedly inflicted on Russia. While it is absurd to depict the White movement as proto-Nazi, with anti-Semitism “a focal point of [its] world-view”244—that was provided by nationalism—it is indisputable that the White officer corps, not to speak of the Cossacks, was increasingly contaminated by it. Even so, it would be a mistake to draw any direct link between this emotional virulence and the anti-Jewish excesses during the Civil War. For one thing, as we shall note, most of the massacres were perpetrated not by Russian White troops but by Ukrainian irregulars and Cossacks. For another, the pogroms were inspired far less by religious and national passions than by ordinary greed: the worst atrocities on the White side were committed by the Terek Cossacks, who had never known Jews and regarded them merely as objects of extortion. Although the anti-Jewish pogroms had certain unique features, in a broader perspective they were part and parcel of the pogroms perpetrated at the time throughout Russia:

Freedom was understood as liberation from restrictions imposed on people by the very fact of common existence and interdependence. For that reason the first to be destroyed were those who in every given locality embodied the idea of statehood, society, system, order. In the cities they were the policemen, administrators, judges; in the factories, the owner or manager, the very presence of whom served as a reminder that one must work to receive pay.… In the villages, it was the neighboring, nearest estate, the symbol of lordship, that is, simultaneously of authority and wealth.245

And in the small towns of the Pale, it was the Jews. Once pogroms and razgromy (destruction of property) became the order of the day, it was inevitable that Jews would be the principal victims: they were seen as aliens, they were defenseless, and were believed rich. The same instincts that led to the destruction of country estates and raids on kulaks led to violence against Jews and their properties. The Bolshevik slogan “grab’ nagrablennoe”—“loot the loot”—made Jews particularly vulnerable to violence because, having been compelled by tsarist legislation to engage in trade and artisanship, they handled money and thus automatically qualified as burzhui.

Anti-Jewish excesses began in 1918 under Hetman Skoropadski during the German occupation of the Ukraine.246 They intensified after the German withdrawal in late 1918, when southern and southwestern Russia fell prey to anarchy. The worst year was 1919, with two peak periods of pogroms, the first in May and the second in August–October. The White Army was involved only in the last phase: until it made its appearance in the central Ukraine in August, the pogroms were perpetrated by the Cossack bands of Petlura, and by outlaws headed by various “fathers” or bat’ko, of whom Grigorev was the most notorious.

The pogroms followed a pattern.

As a rule, they were perpetrated not by the local population, which lived reasonably peacefully alongside the Jews, but by outsiders, either gangs of brigands and deserters formed to engage in plunder, or by Cossack units for whom looting was a diversion from fighting.* The local peasantry participated in the capacity of camp followers, scavengers of spoils that the robbers left behind because they were too bulky to carry.

The primary purpose of pogroms everywhere was plunder: physical violence against Jews was applied mainly to extort money, although mindless sadism was not unknown: “In the overwhelming majority of cases, murder and torture took place only as instruments of plundering.”247 On breaking into a Jewish household, the bandits would demand money and valuables. If these were not forthcoming, they would resort to violence. Most killings were the result of the refusal or inability of the victims to pay up.248 Furniture and other household goods were usually loaded onto military trains for shipment to the Don, Kuban, or Terek territories; sometimes they were smashed, or else distributed to the peasants who stood by with carts and bags. This process, carried out by armed men who moved back and forth with the fortunes of war across areas inhabited by Jews, entailed a methodical extraction from Jews of all their belongings: the first victims were the well-to-do; when they had nothing left, it was the turn of the poor.

Nearly everywhere, pogroms were accompanied by rape. The victims were often killed afterward.

Sometimes, the pogroms had a religious character, resulting in the desecration of Jewish houses of worship, the destruction of Torah scrolls and other religious articles; but on the whole religion played a much smaller role than economic and sexual motives.

The first major incident occurred in January 1919, in the Volhynian town of Ovruch, where an ataman by the name of Kozyr-Zyrka, affiliated with Petlura, flogged and killed Jews to extort money.249 Next came pogroms at Proskurov (February 15) and Felshtin.250 They were followed by massacres at Berdichev and Zhitomir.

Petlura, whose forces carried out most of these pogroms, did not himself encourage violence against Jews—indeed, in an order of July 1919 he prohibited anti-Semitic agitation.251 But he had no control over his troops, which were loosely linked by an anti-Bolshevism that readily shaded into anti-Semitism. When the Red Army occupied the Ukraine following the German evacuation, its policies in no time turned the Ukrainian population against the Bolsheviks; and since among Bolsheviks active in the Ukraine were not a few Jews, the distinction between the two became blurred. Antonov-Ovseenko, who served as Lenin’s proconsul in the Ukraine, in a confidential dispatch to Moscow identified among the various causes of Ukrainian hostility to the Soviet regime, “the complete disregard of the prejudices of the population in the matter of the attitude toward the Jews,” by which he could only have meant the use of Jews as agents of the Soviet government.252

In early 1919 there appeared in the Ukraine gangs headed by Grigorev that laid waste the region of the lower Dnieper between Ekaterinoslav and the Black Sea. Grigorev, an army officer who had served in World War I, at first supported Petlura, but in February 1919 he switched to the Bolsheviks, who appointed him commander of a Red Army division. Heading a troop of up to 15,000 men, mostly peasants from the southern Ukraine, equipped with field guns and armored cars, he represented a considerable force: sufficiently strong, as we have seen, to defeat the French-led contingent in Kherson in March 1919. In early April, he captured Odessa.

Later that month, however, he began to turn against Communist commissars and Jews. He broke openly with the Communists on May 9, after refusing to obey an order to move into Bessarabia to reinforce the Communist government of Hungary: his rebellion frustrated Moscow’s plans to link up with Communist Hungary and caused that government’s fall.253 After mutinying, Grigorev seized Elizavetgrad, where he issued a “Universal,” appealing to peasants to march on Kiev and Kharkov to expel the Soviet government. It was in Elizavetgrad that his men carried out the worst Jewish pogrom up to that time, an orgy of looting, killing, and raping that went on for three days (May 15–17).254 He denounced “hooknosed commissars” and encouraged his followers to rob Odessa, which had a sizable Jewish population, until it was “pulled to pieces.”255 Until their destruction later that month by the Red Army, Grigorev’s bands carried out 148 pogroms. Grigorev lost his life in July at the hands of Makhno, who invited him for talks and then had him murdered.256 Grigorev’s followers, “impressed by this display of gangster technique, mostly joined Makhno.”257

The wave of pogroms receded briefly after Grigorev’s fall but rose again to attain unprecedented ferocity in August, when Denikin’s Cossacks and Petlura’s Ukrainians converged on Kiev, leaving behind a trail of devastation.258

In August and September, as the Volunteer Army was marching from victory to victory and the capture of Moscow seemed imminent, White troops threw caution to the winds: they no longer cared for the opinion of Europe. Moving into the western Ukraine and capturing Kiev, Poltava, and Chernigov, the Cossacks serving in White ranks carried out one vicious pogrom after another. The experience of these summer months, in the words of one historian, demonstrated that where Jews were concerned it was permissible to give free rein to bestial instincts with total impunity.259 Little attempt was made to justify these atrocities: if justification was called for, Jews were accused of favoring Communists and treacherously sniping at White troops.

In Kiev a pogrom carried out by Terek Cossacks between October 17 and 20 claimed close to 300 lives. Night after night, gangs of armed men would break into Jewish apartments, stealing, beating, killing, and raping. V. V. Shulgin, the monarchist editor of the anti-Semitic daily Kievlianin, thus describes the scenes he had witnessed:

At night, the streets of Kiev are in the grip of medieval terror. In the midst of deadly silence and deserted streets suddenly there begins a wail that breaks the heart. It is the “Yids” who cry. They cry from fear. In the darkness of the streets somewhere appear bands of “men with bayonets” who force their way, and, at their sight, huge multistoried houses begin to wail from top to bottom. Whole streets, seized with terrifying dread, howl with an inhuman voice, trembling for their lives. It is terrible to hear these voices of the postrevolutionary night.… This is genuine fear, a true “torture by fear,” to which the whole Jewish population is subjected.260

Shulgin felt that the Jews had brought these horrors upon themselves and worried lest the pogroms arouse sympathy for them.

The worst pogrom of all occurred in Fastov, a small and prosperous trading center southwest of Kiev, inhabited by 10,000 Jews, where on September 23–26 a Terek Cossack brigade commanded by a Colonel Belogortsev engaged in a Nazi-type Aktion: missing were only the vans with carbon monoxide outlets. An eyewitness described what happened:

The Cossacks divided into numerous separate groups, each of three or four men, no more. They acted not casually … but according to a common plan.… A group of Cossacks would break into a Jewish home, and their first word would be “Money!” If it turned out that Cossacks had been there before and had taken all there was, they would immediately demand the head of the household.… They would place a rope around his neck. One Cossack took one end, another the other, and they would begin to choke him. If there was a beam on the ceiling, they might hang him. If one of those present burst into tears or begged for mercy, then—even if he were a child—they beat him to death. Of course, the family surrendered the last kopeck, wanting only to save their relative from torture and death. But if there was no money, the Cossacks choked their victim until he lost consciousness, whereupon they loosened the rope. The unfortunate would fall unconscious to the floor, after which, with blows of the rifle butt or even cold water, they brought him back to his senses. “Will you give money?” the tormentors demanded. The unfortunate swore that he had nothing left, that other visitors had taken everything away. “Never mind,” the scoundrels told him, “you will give.” Once again they would put the rope around his neck and again choke or hang him. This was repeated five or six times.…

I know of many homeowners whom the Cossacks forced to set their houses on fire, and then compelled, with sabers or bayonets, along with those who ran out of the burning houses, to turn back into the fire, in this manner causing them to burn alive.261

In Fastov, the victims were mainly older people, women, and children, apparently because the able-bodied men had managed to flee. They were ordered stripped naked, sometimes tortured, required to shout, “Beat Yids, save Russia,” and cut down with cavalry sabers; the corpses were left to be devoured by pigs and dogs. Sexual assaults were frequent, and second in frequency to looting: everywhere women were raped, sometimes in public. The Fastov massacre is said to have claimed 1,300–1,500 lives.*

While the Cossack detachments of the Southern Army committed numerous atrocities (none can be attributed to the Volunteer Army), a careful reckoning of the pogroms by Jewish organizations indicates that the worst crimes were the work of independent gangs of Ukrainians.* According to these analyses, during the Civil War there occurred 1,236 incidents of anti-Jewish violence, of which 887 are classified as pogroms and the rest as “excesses,” that is, violence that did not assume mass proportions.262 Of this total number, 493, or 40 percent, were committed by the Ukrainians of Petlura, 307 (25 percent) by independent warlords or atamans, notably Grigorev, Zelenyi, and Makhno, 213 (17 percent) by the troops of Denikin, and 106 (81/2 percent) by Red Army units (on the last, historical studies are strangely silent).† The main element responsible for the atrocities committed by the Whites, the Cossacks, had been lured away from their settlements not by the vision of a restored and unified Russia but by the prospect of loot and rape: one Cossack commander said that after hard fighting his boys deserved four or five days of “rest” to inspire them for the next battle.263

While it is, therefore, incorrect to lay wholesale blame for the massacres of the Jews on the White Army, it is true that Denikin remained passive in the face of these atrocities, which not only stained the reputation of his army but also demoralized it. Denikin’s propaganda bureau, Osvag, bore much responsibility for spreading anti-Semitic propaganda, and the harm was compounded by the tolerance shown to the anti-Semitic publications of Shulgin and others.

Personally, Denikin was not a typical anti-Semite of the time: at any rate, in his five-volume chronicle of the Civil War he does not blame Jews either for Communism or for his defeat. On the contrary: he expresses shame at their treatment in his army as well as the pogroms and shows awareness of the debilitating effect these had on the army’s morale. But he was a weak, politically inexperienced man who had little control over the behavior of his troops. He yielded to the pressures of anti-Semites in his officer corps from fear of appearing pro-Jewish and from a sense of the futility of fighting against prevailing passions. In June 1919 he told a Jewish delegation that urged him to issue a declaration condemning the pogroms, that “words here were powerless, that any unnecessary clamor in regard to this question will only make the situation of Jews harder, irritating the masses and bringing out the customary accusations of ‘selling out to the Yids.’ ”‡ Whatever the justice of such excuses for passivity in the face of civilian massacres, they must have impressed the army as well as the population at large that the White Army command viewed Jews with suspicion and if it did not actively encourage pogroms, neither was it exercised about them.

The claim has been made that among “the thousands of documents in the White Army archives there is not one denunciation of pogroms.”264 The claim is demonstrably wrong. Denikin says, and the evidence supports him, that he and his generals issued orders condemning the pogroms and calling for the perpetrators to be severely punished.265 On July 31, 1919, General Mai-Maevskii demanded that equal treatment be accorded all citizens: persons violating this principle were to be punished. He dismissed a Terek general implicated in pogroms.266 On September 25, when the pogroms were at their height, Denikin instructed General Dragomirov to discipline severely military personnel guilty of them.267 But anti-Jewish hysteria made it impossible to enforce such orders.* For instance, in obedience to Denikin’s instructions, Dragomirov ordered court-martials for officers involved in the Kiev pogrom and had three of them sentenced to death, but he was forced to rescind the sentence after fellow officers threatened to avenge their execution by a pogrom against Kievan Jews in which hundreds would perish.268

The anti-Semitism of the Southern Army has been well documented and publicized. Little attention has been paid to Soviet reactions. The Sovnarkom is said on July 27, 1918, to have issued an appeal against anti-Semitism, threatening penalties for pogroms.269 But the following year, when the wave of pogroms was rising, Moscow was conspicuously silent. Lenin issued on April 2, 1919, a condemnation of anti-Semitism in which he argued that not every Jew was a class enemy—the implication being that some were, but just how to distinguish between those who were and those who were not, he did not say.270 In June, the Soviet government assigned funds to help certain victims of pogroms.271 But Lenin no more condemned the Ukrainian pogroms than did Denikin, and probably for the same reasons. The Soviet press ignored the subject.272 “Playing up” these atrocities, it turns out, was for the Communists “not good propaganda.”273 By the same token, neither was it good propaganda for the Whites.

The only prominent public figure to condemn the pogroms openly and unequivocally was the head of the Orthodox Church, Patriarch Tikhon. In an Epistle issued on July 21, 1919, he called violence against Jews “dishonor for the perpetrators, dishonor for the Holy Church.”274

The number of fatalities suffered in the pogroms of 1918–21 cannot be ascertained with any precision, but it was high. Evidence exists that 31,071 victims were given a burial.275 This figure does not include those whose remains were burned or left unburied. Hence, it is commonly doubled and even tripled, to anywhere between 50,000 and 200,000.* Accompanying these massacres were immense losses of property: Ukrainian Jews were left impoverished, many of them destitute and homeless.

In every respect except for the absence of a central organization to direct the slaughter, the pogroms of 1919 were a prelude to and rehearsal for the Holocaust. The spontaneous lootings and killings left a legacy that two decades later was to lead to the systematic mass murder of Jews at the hands of the Nazis: the deadly identification of Communism with Jewry.

In view of the role this accusation had in paving the way for the mass destruction of European Jewry, the question of Jewish involvement in Bolshevism is of more than academic interest. For it was the allegation that “international Jewry” invented Communism as an instrument to destroy Christian (or “Aryan”) civilization that provided the ideological and psychological foundation of the Nazi “final solution.” In the 1920s the notion came to be widely accepted in the West and the Protocols became an international best-seller. Fantastic disinformation spread by Russian extremists alleged that all the leaders of the Soviet state were Jews.276 Many foreigners involved in Russian affairs came to share this belief. Thus, Major General H. C. Holman, head of the British military mission to Denikin, told a Jewish delegation that of 36 Moscow “commissars” only Lenin was a Russian, the rest being Jews. An American general serving in Russia was convinced that the notorious Chekists M. I. Latsis and Ia. Kh. Peters, who happened to be Latvians, were Jewish as well.277 Sir Eyre Crowe, a senior official in the British Foreign Office, responding to Chaim Weizmann’s memorandum protesting the pogroms, observed “that what may appear to Mr. Weizmann to be outrages against Jews, may in the eyes of the Ukrainians be retaliation against the horrors committed by the Bolsheviks who are all organized and directed by the Jews.”† For some Russian Whites, anyone who did not wholeheartedly support their cause, whether Russian or Western, including President Wilson and Lloyd George, was automatically presumed to be a Jew.

What are the facts? Jews undeniably played in the Bolshevik Party and the early Soviet apparatus a role disproportionate to their share of the population. The number of Jews active in Communism in Russia and abroad was striking: in Hungary, for example, they furnished 95 percent of the leading figures in Bela Kun’s dictatorship.278 They also were disproportionately represented among Communists in Germany and Austria during the revolutionary upheavals there in 1918–23, and in the apparatus of the Communist International. But then Jews are a very active people, prominent in many fields of endeavor. If they were conspicuous in Communist circles, they were no less so in capitalist ones (according to Werner Sombart, they invented capitalism), not to speak of the performing arts, literature, and science. Although they constitute less than 0.3 percent of the world’s population, in the first seventy years of the Nobel Prizes (1901–70), Jews won 24 percent of the awards in physiology and medicine, and 20 percent of those in physics. According to Mussolini, four of the seven founders of the Fascist Party were Jews;* Hitler said that they were among the early financial supporters of the Nazi movement.279

Nor must it be deduced from the prominence of Jews in the Communist government that Russian Jewry was pro-Communist. The Jews in Communist ranks—the Trotskys, Zinovievs, Kamenevs, Sverdlovs, Radeks—did not speak for the Jews, because they had broken with them long before the Revolution. They represented no one but themselves. It must never be forgotten that during the Revolution and Civil War, the Bolshevik Party was very much a minority party, a self-selected body whose membership did not reflect the politics of the population: Lenin admitted that the Communists were a drop of water in the nation’s sea.280 In other words, while not a few Communists were Jews, few Jews were Communists. When Russian Jewry had the opportunity to express its political preferences, as it did in 1917, it voted not for the Bolsheviks, but either for the Zionists or for parties of democratic socialism.† The results of the elections to the Constituent Assembly indicate that Bolshevik support came not from the region of Jewish concentration, the old Pale of Settlement, but from the armed forces and the cities of Great Russia, which had hardly any Jews.‡ The census of the Communist Party conducted in 1922 showed that only 959 Jewish members had joined before 1917.§ It was only half in jest that the Chief Rabbi of Moscow, Jacob Mazeh, on hearing Trotsky deny he was a Jew and refuse to help his people, commented that it was the Trotskys who made the revolutions and the Bronsteins who paid the bills.281

In the course of the Civil War, the Jewish community, caught in the Red-White conflict, increasingly sided with the Communist regime: this, however, it did not from preference but from the instinct of self-preservation. When the White armies entered the Ukraine in the summer of 1919, Jews welcomed them, for they had suffered grievously under the Bolshevik rule—if not as Jews then as “bourgeois.”282 They quickly became disenchanted with White policies that tolerated pogroms and excluded Jews from the administration. After experiencing White rule, Ukrainian Jewry turned anti-White and looked to the Red Army for protection. Thus a vicious circle was set in motion: Jews were accused of being pro-Bolshevik and persecuted, which had the effect of turning them pro-Bolshevik for the sake of survival; this shift of allegiance served to justify further persecutions.

For all practical purposes, Admiral Kolchak’s army ceased to exist in November 1919, when it turned into a rabble guided by the principle sauve qui peut. Thousands of officers with their families and mistresses, as well as hordes of soldiers and civilians, rushed headlong eastward: those who could afford it, by train, the rest by horse and cart or on foot. The wounded and the ill were abandoned. In the no-man’s-land between the advancing and retreating armies, marauders, mostly Cossacks, robbed, killed, and raped. All semblance of authority disappeared. Russians were accustomed to being told what to do: traditionally, political initiative took for them the form of defiance. But now when there was no one to give orders and therefore no one to defy, they foundered. Foreign observers were struck by the fatalism of Russians in face of disaster: one of them remarked that when in distress, the women would cry and the men take to drink.

All streamed to Omsk in the hope that it would be defended: the influx of refugees swelled the city from a population of 120,000 to over 500,000:

When the main body of [Kolchak’s] troops arrived at Omsk they found unspeakable conditions. Refugees overflowed the streets, the railroad station, the public buildings. The roads were hub-deep in mud. Soldiers and their families begged from house to house for bread. Officers’ wives turned into prostitutes to stave off hunger. Thousands who had money spent it in drunken debauches in the cafés. Mothers and their babies froze to death upon the sidewalks. Children were separated from their parents and orphans died by the score in the vain search for food and warmth. Many of the stores were robbed and others closed through fear. Military bands attempted a sorry semblance of gaiety in the public houses but to no avail. Omsk was inundated in a sea of misery.… The condition of the wounded was beyond description. Suffering men often lay two in a bed and in some hospitals and public buildings they were placed on the floor. Bandages were improvised out of sheeting, tablecloths, and women’s underclothing. Antiseptics and opiates were almost nonexistent.283

Kolchak wanted to defend Omsk, but he was dissuaded by General M. K. Diterikhs, whom he had appointed in place of Lebedev as Chief of Staff. Omsk was evacuated on November 14. The Reds took the city without a fight: by this time they enjoyed a twofold numerical preponderance, fielding 100,000 men against Kolchak’s 55,000.284 They captured a great deal of booty that was supposed to have been blown up but was not because they had arrived sooner than expected: three million rounds of ammunition and 4,000 railway cars; 45,000 recruits about to be inducted were taken prisoner, along with 10 generals.285

After the fall of Omsk, the flow of refugees streaming eastward turned into a flood. An English officer who had witnessed the rout recalled it as a nightmare:

Tens of thousands of peaceful people had fled into Siberia during that space of time, rushing away from that Red Terror with nothing but the clothes they stood in, as people rush in their nightdresses out of a house on fire, as the farmer on the slopes of Vesuvius rushes away from the flaming river of lava. Peasants had deserted their fields, students their books, doctors their hospitals, scientists their laboratories, workmen their workshops, authors their completed manuscripts.… We were being swept along in the wreckage of a demoralized army.286

The misery was compounded by typhus, a disease communicated by body lice, which thrive in unsanitary conditions, especially in the winter. Infected Russians showed no concern for others, with the result that typhus spread unchecked among the troops and civilian refugees, claiming countless victims: “When I passed Novonikolaevsk on February 3, [1920],” writes the same eyewitness,

there were 37,000 typhus cases in that town, and the rate of mortality, which had never been more than 8 percent, had risen to 25 percent. Fifty doctors had died in that town alone during the space of one month and a half and more than 20,000 corpses lay unburied outside the town.… Conditions in the hospitals were indescribable. In one … the head doctor had been fined for drunkenness, the other doctor only paid the place a short visit once a day, and the nurses only put in an appearance while the doctor was there. The linen and the clothes of the patients were never changed, and most of them lay in a most filthy condition in their everyday clothes on the floor. They were never washed, and the male attendants waited for the periodical attacks of unconsciousness which are characteristic of typhus in order to steal from the patients their rings, jewelry, watches and even their food.287

Entire trains, filled with the sick, dying, and dead, littered the Transsiberian Railroad. These ravages could have been avoided or at least contained by the observance of minimal sanitary precautions. Czechoslovak troops living in the midst of the epidemic managed to escape it, and so did U.S. soldiers in Siberia.

Kolchak left Omsk for Irkutsk, his new capital, on November 13, just ahead of the Red Army. He traveled in six trains, one of which, made up of 29 cars, carried the gold and other valuables which the Czechs had captured in Kazan and turned over to him. Accompanying him were 60 officers and 500 men. The Transsiberian between Omsk and Irkutsk was guarded by the Czechoslovak Legion. Billeted in tidy trains, the Czechs lived in relative luxury: exchanging the French francs they received in pay from Paris by way of Tokyo into rapidly depreciating rubles, they bought up (when they did not steal) everything of value.288 On orders of their general, Jan Syrovy, who worked closely with General Janin, they delayed Russian trains moving east, sidetracking Kolchak for over a month between Omsk and Irkutsk, to let through their own.289 At the end of December, seven weeks after he had left Omsk, Kolchak was stranded at Nizhneudinsk, 500 kilometers west of Irkutsk, forsaken by virtually everyone and kept incommunicado by his Czech guards.

On Christmas Eve 1919, a coalition of left-wing groups, dominated by Socialists-Revolutionaries but including Mensheviks, leaders of local self-government boards, and trade unionists, formed in Irkutsk a “Political Center.” After two weeks of alternate fighting and negotiating with the pro-Kolchak elements, the Center took over the city. Declaring Kolchak deposed, it proclaimed itself the government of Siberia. Kolchak, “an enemy of the people,” and other participants in his “reactionary policies” were to be brought to trial. Some of Kolchak’s ministers took refuge in the trains of the Allied missions: most fled, disguised, in the direction of Vladivostok. On learning of these events on January 4, 1920, Kolchak announced his resignation in favor of Denikin and the appointment of Ataman Semenov as Commander in Chief of all the military forces and civilians in Irkutsk province and areas to the east of Lake Baikal. He then placed himself and the gold hoard under the protection of the Czechs and, at their request, dismissed his retinue. Having decked Kolchak’s trains with the flags of England, the United States, France, Japan, and Czechoslovakia, the Czechs undertook to escort him to Irkutsk and there to turn him over to the Allied missions.290 While this was happening, Semenov proceeded to massacre socialists and liberals in eastern Siberia, including the hostages whom pro-Kolchak elements had imprisoned following the Irkutsk coup.*

What happened subsequently has never been satisfactorily explained. As best as can be determined, Kolchak was betrayed by Generals Janin and Syrovy, with the result that instead of receiving Allied protection he was handed over to the Bolsheviks.† Janin, who from the moment of his arrival in Siberia had treated Kolchak as a British stooge whom he wished to be rid of, now had his chance. The Czechs wanted home. The French general, formally their commander, struck a deal with the Political Center on their behalf, arranging safe passage to Vladivostok for them and their loot in exchange for Kolchak and his gold. Having made these arrangements, he left Irkutsk.

On reaching Irkutsk in the evening of January 14, the Czechs informed Kolchak that on orders of General Janin he was to be turned over to the local authorities. The next morning, Kolchak, along with his mistress, the 26-year-old A. V. Kniper, and his Prime Minister, V. Pepelaev, were taken off the train and put in prison.

On January 20, Irkutsk learned that General Kappel, one of Kolchak’s bravest and most loyal officers, was approaching at the head of an armed force to free Kolchak. On hearing this news, the Political Center, which had never exercised effective power anyway, dissolved and transferred authority to the Bolshevik Military-Revolutionary Committee. The Milrevkom agreed to allow the Czechs to proceed east, whereupon the Czechs turned over to it Kolchak’s treasure.*

The new authority in Irkutsk formed a commission chaired by a Bolshevik and composed of another Bolshevik, two SRs, and a single Menshevik to “investigate” Kolchak and his rule. The commission sat from January 21 to February 6, 1920, interrogating Kolchak about his past and his activities as Supreme Ruler. Kolchak behaved with great dignity: the minutes of the testimony reveal a man in complete command of himself, aware that he was doomed but confident that he had nothing to hide and that history would vindicate him.291

The investigation, a cross between an inquest and a trial, was abruptly terminated on February 6, when the Irkutsk Revkom sentenced Kolchak to death. The official explanation given for the execution, when the news was made public several weeks later, was that Irkutsk had learned that General Voitsekhovskii, who had succeeded Kappel after the latter’s death on January 20, was drawing near and there was danger of Kolchak being abducted.292 But a document found in the Trotsky Archive at Harvard University raises serious doubts about this explanation and suggests that, as in the case of the murder of the Imperial family, it was an excuse to conceal that the execution had been ordered by Lenin. The order—scribbled by Lenin on the back of an envelope and addressed to I. N. Smirnov, Chairman of the Siberian Military-Revolutionary Council—reads as follows:

Cypher. Sklianskii: send to Smirnov

(Military-Revolutionary Council of the Fifth Army) the cypher text:

Do not put out any information about Kolchak; print absolutely nothing but, after our occupation of Irkutsk, send a strictly official telegram explaining that the local authorities, before our arrival, acted in such and such a way under the influence of the threat from Kappel and the danger of White Guard plots in Irkutsk. Lenin

[Signature also in cypher.]

1. Do you undertake to do this with utmost reliability? … January 1920293

The editors of the Trotsky Papers, normally very cautious, who had first made this document public, assumed that the date “January 1920” was in error and that the document was actually written after February 7, the day of Kolchak’s execution.294 There are no grounds for such an assumption. The whole procedure ordered by Lenin closely recalls that employed to camouflage the murder of the Imperial family—the killing allegedly done on the initiative of local authorities from fear that the prisoner would be abducted and the Center learning of it only after the fact. The explanations offered were meant to remove from Lenin the onus for executing a defeated military commander, and one, moreover, who was highly regarded in England, with which Soviet Russia was then initiating trade talks. Lenin’s instructions were almost certainly sent before Kolchak’s execution, and probably before Kappel’s death on January 20.* The message must have been received in Irkutsk on February 6, when the interrogation of Kolchak was abruptly terminated.

The incoherent verdict of the Irkutsk Revolutionary Committee read:

The ex-Supreme Ruler, Admiral Kolchak, and the ex-Chairman of the Council of Ministers, Pepelaev, are to be shot. It is better to execute two criminals, who have long deserved death, than hundreds of innocent victims.295

When informed in the middle of the night, Kolchak asked: “This means that there will be no trial?” For he had not been charged. A poison pill concealed in a handkerchief was taken from him. He was denied a farewell meeting with Kniper. As he was being led to his execution in the early hours of the morning, Kolchak requested the Chekist commander to convey to his wife in Paris a blessing for their son. “I will if I don’t forget,” the executioner replied.296 Kolchak was shot at four a.m. on February 7, along with Pepelaev and a Chinese criminal. He refused to have his eyes bound. The bodies were pushed under the ice in the Ushakovka River, a branch of the Angara.

One month later (March 7), the Red Army took Irkutsk. Although the foreign press had already carried reports to this effect, it was only now that Smirnov, following Lenin’s orders, informed Moscow of Kolchak’s execution the previous month, allegedly on orders of the local authorities to prevent his capture by the Whites or Czechs(!).297

At Irkutsk the Red Army halted its advance, because it could not afford to become involved in hostilities with Japan and the Russian warlords under her protection.298 For the time being, Siberia east of Lake Baikal was left to the Japanese. On April 6, 1920, the Soviet government created in eastern Siberia a fictitious “Far Eastern Republic” with a capital in Chita. When the Japanese withdrew from eastern Siberia two and a half years later (October 1922), Moscow incorporated this territory into Soviet Russia.

Astonishing as it seems, the Cheka was entirely oblivious of the pro-White underground organization the National Center and its intelligence activities until the summer of 1919, when a series of fortuitous accidents put it on the Center’s trail.

The Cheka’s suspicions were first aroused by the betrayal of Krasnaia Gorka, a strategic fortress protecting access to Petrograd, during Iudenich’s May 1919 offensive.299 At that time, documents were found on a man who was attempting to cross into Finland, containing passwords and codes by means of which Iudenich was to communicate with supporters in Petrograd.300 Investigation revealed the existence of a National Center engaged in espionage and other intelligence activities.

In the third week of July a Soviet border patrol arrested two other men attempting to cross into Finland. During the interrogation, one of them tried to dispose of a packet that turned out to contain coded documents with information on deployments of the Red Army in the Petrograd region provided by a clandestine organization in that city.301 Apparently the two prisoners cooperated, because a few days later the Cheka raided the apartment of the engineer Vilgelm Shteininger. The papers found in his possession indicated that he was the central figure of the Petrograd National Center.302 On the Cheka’s orders, Shteininger prepared memoranda on the National Center, the Union for the Regeneration of Russia, and other underground organizations. Although he was careful not to betray names, the Cheka succeeded in identifying and arresting several of his accomplices. They were brought to Moscow for interrogation by the “Special Department” of the Cheka, which revealed a clandestine organization far more extensive than the Soviet authorities had suspected. In view of Denikin’s advance on Moscow, it was essential to uncover it fully: another Krasnaia Gorka could have fatal consequences. But the interrogations provided few specific clues.

Another stroke of good luck helped the Cheka solve the riddle. On July 27, a Soviet patrol in Viatka province in northern Russia detained a man who could not produce proper identity papers: on his person were found nearly one million rubles and two revolvers. He identified himself as Nikolai Pavlovich Krashennininkov; the money which he carried he said was given him by Kolchak’s government and was to be turned over to a man, unknown to him, who would meet him at the Nikolaevskii railroad station in Moscow. Krashennininkov was sent to the Lubianka, but divulged nothing more. The Cheka then placed in his prison cell an agent provocateur, an officer who pretended to belong to the National Center. The latter offered, with the help of his wife, to convey messages to Krashennininkov’s friends. Krashennininkov fell for the ruse. On August 20 and 28 he sent two messages, in the second of which, addressed to N. N. Shchepkin, he requested poison.303

The 65-year-old Shchepkin was the son of an emancipated serf who had acquired fame as a Gogolian actor. A Kadet and an attorney, he had served in the Third Duma. In 1918 he had joined both the Right Center and the Union for Regeneration, which made him one of the few persons to belong to both organizations. After most of his associates had fled Soviet Russia to escape the terror, he remained at his post, maintaining communications with Kolchak, Denikin, and Iudenich. A typical message from him sent to Omsk in May or June 1919 and signed “Diadia Koka” (Uncle Coca) described the mood of the population under Communist rule, criticized the socialist intelligentsia as well as Denikin, and urged Kolchak to release an unambiguous programmatic statement.304 Shchepkin knew of the arrests in Petrograd and the danger he faced. At the end of August he told a friend: “I feel that the circle is progressively tightening. I feel we shall all die, but this is not important: I have long been prepared for death. Life holds no value for me: all that matters is that our cause not fail.”305

At ten p.m. on August 28, following the lead provided by Krashennininkov’s second letter, the Cheka arrested Shchepkin in his wooden lodge on the corner of Neopalimovskii and Trubnyi lanes, and took him to the Lubianka, leaving behind agents. Shchepkin and his fellow conspirators had foreseen such a contingency and taken precautions to limit the damage: if the house was safe, a pot with white flowers would stand in the window; if it was not there, the house was to be avoided. After Shchepkin’s arrest, with Cheka agents inside, the pot could not be removed, and as a result many of the conspirators walked into a trap.306 During his interrogation, Shchepkin, resisting threats, withheld information that could incriminate others.307 But in a box found in his garden were secret messages with military and political intelligence, among them suggested texts of slogans for Denikin’s use on approaching Moscow (“Down with the Civil War, Down with the Communists, Free trade and private property. On the soviets, maintain silence”).308

On September 23, the Communist press published the names of 67 members of a “counterrevolutionary and espionage” organization who had been executed. The list was headed by Shchepkin and included Shteininger and Krashennininkov: the majority were officers, members of the military branch of the Center. An editorial in Izvestiia labeled the victims “bloodthirsty leeches” responsible for the death of countless workers.* They had been interrogated around the clock. The executions were carried out to the sound of running truck engines in the Lubianka courtyard to muffle the shots. The corpses were driven to the Kalitnikov Cemetery and dumped into a common grave.

13. Shchepkin.

On September 12, 1919, Denikin ordered his troops “from the Volga to the Romanian border” to advance on Moscow.309 On September 20 the Volunteer Army seized Kursk.

Alarmed by his progress, the Soviet leaders on September 24 designated a “final defense line” running from Moscow to Vitebsk, the Dnieper River, Chernigov, Voronezh, Tambov, Shatsk, and back to Moscow. This entire area, the capital city included, came under martial law.310 In greatest secrecy, plans were laid for the evacuation of the Soviet government to Perm: lists of personnel and offices to be moved were drawn up; Dzerzhinskii instructed the Cheka to divide its 12,000 hostages into categories in order to determine which to execute first to prevent their falling into White hands.311

The Whites soon pierced this defensive perimeter, capturing Voronezh on October 6 and Chernigov on October 12. On October 13–14, just as Iudenich’s troops were fighting in Gatchina, not far from Petrograd, the Volunteer Army took Orel. It was the high-water mark of the Whites’ advance: at this point, their forces stood 300 kilometers from Moscow and within sight of Petrograd. Their advance seemed unstoppable, the more so as masses of Red troops were deserting to them. The next objective of the Volunteers was Tula, the last major city on the road to the capital, and for the Reds a critical asset because it housed its most important defense industries.312 The Red command was determined to prevent its fall at any price.

The Red Army kept on transferring to the south troops from the Eastern front, where the fighting was, for all practical purposes, over. But it also stripped the Western front: it was now that Pilsudski’s pledge not to threaten the Red Army proved so valuable. In all, between September and November, the Southern front received an additional 270,000 men, which gave it an insuperable numerical advantage in the impending battles.313

On October 11, while the fighting in the south was reaching a climax, Iudenich launched his second offensive against Petrograd. The old capital had little strategic value, although it was a major center of war industry: but its capture was expected to have an incalculable effect on Communist morale. At the start of the campaign, Iudenich’s force consisted of 17,800 infantry, 700 cavalry, 57 guns, 4 armored trains, 2 armored cars, and 6 tanks manned by Englishmen. Opposing it stood the Red Seventh Army with 22,500 infantry, 1,100 cavalry, 60 guns, 3 armored trains, and 4 armored cars. By the time the Whites drew near to Petrograd, however, the Red force had tripled in size.314 The British military mission promised Iudenich to blockade Petrograd and to give naval support against Kronshtadt, the naval base located on an island in the Gulf of Finland, and against the batteries defending Petrograd.

On the eve of his offensive, Iudenich released a declaration stating that his government represented all the strata and classes of the population, that it rejected tsarism and would guarantee the rights of peasants to the land and workers to an eight-hour day.315

Iudenich’s force made rapid progress against a demoralized Seventh Red Army. On October 16 it stood at Tsarskoe Selo, the old Imperial residence, a mere 25 kilometers from Petrograd. The Whites, among whom were many officers serving as ordinary soldiers, fought brilliantly, using night as a cover to disorient and frighten the enemy, creating the impression that he was greatly outnumbered. The appearance of tanks invariably threw the Reds into headlong flight. Iudenich was aided by Colonel V. A. Liundekvist, Chief of Staff of the Seventh Red Army, who conveyed to the Whites his army’s dispositions and operational plans.316 Participating were units of the RAF and the British navy, which provided artillery cover and bombed Kronshtadt, sinking, capturing, or severely damaging eleven Soviet ships, including two battleships.*

Critical Battles

OCTOBER–NOVEMBER 1919

To Lenin, the situation in Petrograd seemed hopeless and he was prepared to sacrifice the former capital to hold the line against Denikin. But Trotsky thought otherwise; he managed to change Lenin’s mind and persuaded him to issue orders to defend Petrograd “to the last drop of blood.” At the same time, secret preparations were set in motion to evacuate the city.317 Because Zinoviev had suffered something close to a nervous collapse, Trotsky was dispatched to Petrograd to take charge of the defense. Arriving on October 17, he found the army demoralized, retreating without giving battle in “shameful panic” followed by “senseless flight.”318 His first task was to boost morale and this he accomplished brilliantly. He replaced the commander of the Seventh Army with a general enjoying greater confidence among the troops. In addresses to the soldiers, he made light of their fears, assuring them that the enemy was outnumbered and attacked at night to conceal his weakness. He mocked the tank as “nothing but a metal wagon of special construction.”319 On his orders, the Putilov plant hastily modified a few vehicles to resemble tanks. It was the only engagement in the Civil War in which Trotsky’s presence decisively affected the outcome. He did this largely on his own. Lenin’s advice was useless: on October 22 he urged Trotsky to mobilize “10 thousand or so of the bourgeoisie, post machine guns in their rear, [have] a few hundred shot and assure a real mass assault on Iudenich.”320

Once the Red force stopped panicking, the outcome could not be in doubt, because of its numerical superiority. The Whites with 14,400 men and 44 guns confronted a Seventh Red Army that now numbered 73,000 men supported by 581 guns.321 To make matters worse for Iudenich, to the south stood another Red Army, the Fifteenth.

Iudenich’s soldiers came nearest to Petrograd on October 20, when they occupied Pulkovo. Trotsky, mounted on a horse, rallied the fleeing troops and led them back into battle.322 A critical factor in Iudenich’s defeat was the failure of one of his officers, eager to be the first to enter liberated Petrograd, to obey orders to cut the railroad line to Moscow. This permitted the Red command to dispatch reinforcements, including 7,000 highly motivated Communists and military cadets who stiffened morale and turned the tide of battle.

On October 21, the Seventh Army counterattacked. It quickly pierced the White lines, behind which stood no reserves. Iudenich’s men held out for a while at Gatchina, but then the Fifteenth Red Army began to advance, capturing Luga (October 31) and threatening their rear. Iudenich’s army had no choice but to retreat to Estonia, where it was disarmed.

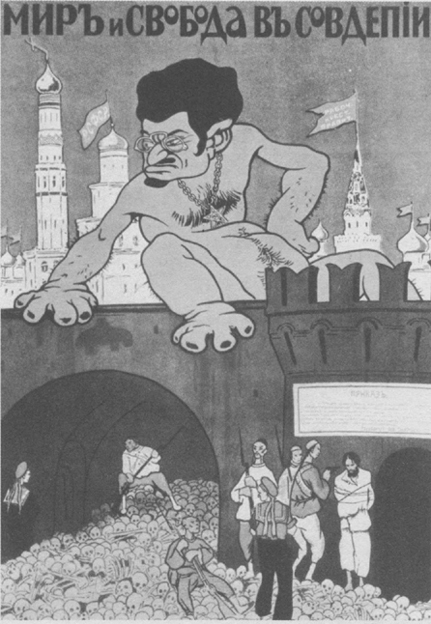

14. Barricades in Petrograd, October 1919.

On December 13, Estonia and Soviet Russia signed an armistice, which was followed on February 2, 1920, by a peace treaty. Lithuania, Latvia, and Finland made peace with Soviet Russia later that year.

To honor his role in the defense of the city, Gatchina was in 1923 renamed Trotsk, the first Soviet city to be named after a living Communist leader.

Toward the end of September 1919, the Red High Command assembled in great secrecy between Briansk and Orel a “Striking Group” (Udarnaia Gruppa) of shock troops. Its nucleus was the Latvian Rifle Division, dressed in its familiar leather jackets, which had been transferred from the Western front and was about, once again, to render the Communist regime an invaluable service.323 Attached was a brigade of Red Cossacks, and several smaller units; it was later reinforced by an Estonian Rifle Brigade.324 The group’s overall strength was 10,000 infantry, 1,500 cavalry, and 80 guns.325 Its command was entrusted to A. A. Martusevich, the head of the Latvian Rifle Division.

The order of battle on the eve of the decisive engagements is not easy to determine. According to Denikin, at the beginning of October the Red Army had on the Southern and Southeastern fronts 140,000 men. His own forces numbered 98,000.326 According to the Red Army commander of the Southern front, the Reds had 186,000 troops.327

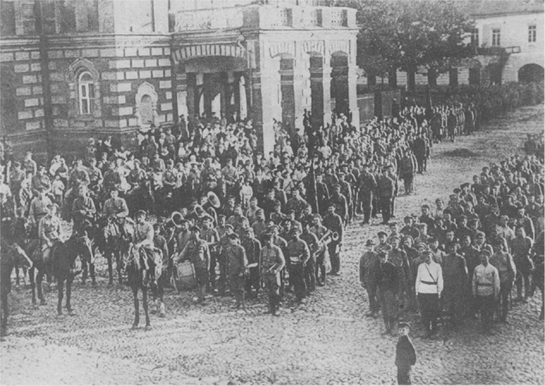

15. Latvian troops about to be dispatched to the Southern front, 1919.

On the very eve of the Red Army’s decisive victories over the Southern Army, Trotsky addressed to the Central Committee a characteristically long and cantankerous letter. The entire planning of the campaign against Denikin, he wrote, had been faulty from the start in that instead of striking at Kharkov to cut him off from his Cossack supporters, the Red Army attacked the Cossacks, pushing them into Denikin’s arms and enabling him to occupy the Ukraine. As a result, the situation in the south had deteriorated and Tula itself was endangered. Lenin jotted down on Trotsky’s letter: “Received October 1. (Nothing but bad nerves.) This was not raised at the Plenum. It is strange to do so now.”328

On October 11, A. I. Egorov was appointed commander of the Southern front. A career officer, he had in his youth belonged to the Socialists-Revolutionaries; wounded several times during World War I, he rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel. In July 1918 he joined the Communist Party. Together with the Commander in Chief, Kamenev, he was the architect of the Red victory.* Egorov reinforced the Striking Group by massing east of Voronezh a newly formed cavalry corps under Semen Budennyi, an “outlander” from the Don who passionately hated the Cossacks.*

16. Budennyi and Egorov.

The Soviet High Command worked out a strategic plan whose main objective was to separate the Volunteer Army from the Don Cossacks, and pour into the breach Budennyi’s cavalry. The Volunteers would then either have to retreat or find themselves in a trap.329† The Red counteroffensive was launched ahead of schedule because Egorov feared further retreats would demoralize his troops and cause their “complete disintegration.”330

On October 18–19, as the Volunteer Army pushed toward Tula, the Second and Third Latvian Brigades launched a surprise attack against the left flank of the Drozdovskii and Kornilov divisions. In pitched battles, the Latvians defeated the exhausted Volunteers and on October 20 forced them to evacuate Orel by threatening to cut off their communications to the rear. In this decisive engagement of the Civil War the main force on the Communist side, the Latvians, lost in killed and wounded over 50 percent of the officers and up to 40 percent of the soldiers.331

17. Budennyi’s Red Cavalry.

The situation of the Volunteer Army was perilous, but far from catastrophic, when suddenly from the east appeared another threat, Budennyi’s Cavalry Corps, reinforced by 12,000–15,000 infantry. On October 19, Budennyi’s horsemen defeated the Don Cossacks under Generals Mamontov and A. G. Shkuro, destroying the flower of the Don cavalry, following which, on October 24, they took Voronezh. According to Denikin, this disaster was brought about by the unwillingness of the Don Cossacks—who were more interested in defending their home territory than in defeating the Red Army—to deploy adequate forces at Voronezh.332 From Voronezh, Budennyi continued westward, and on October 29 crossed the Don River. His orders were to seize Kastornoe, an important railroad junction linking Kursk with Voronezh, and Moscow with the Donbass. The assault on Kastornoe began on October 31. The fighting was fierce. The Red Cavalry finally captured the town on November 15, sealing the fate of the White advance on Moscow. Threatened with being cut off from the Don region, the three divisions of the Volunteer Army had to retreat. They did so in good order, falling back on Kursk. But their commander, General Mai-Maevskii, went completely to pieces, drinking, womanizing, and attending to his loot.333 He was dismissed and replaced by Wrangel.

In the midst of these ordeals another heavy blow fell on the Whites. On November 8, Lloyd George in a speech at the Lord Mayor’s Banquet in Guildhall, London, declared that Bolshevism could not be defeated by force of arms, that Denikin’s drive against Moscow had stalled, and “other methods must be found” to restore peace. “We cannot … afford to continue so costly an intervention in an interminable civil war.”334 The speech had not been cleared with the cabinet and startled many Britons.335 The Prime Minister explained the rationale for this turnabout in an address on November 17 to the House of Commons, from which it transpired that behind it lay fear not of White defeat but of White victory. Disraeli, the Prime Minister recalled, had warned against “a great, gigantic, colossal, growing Russia rolling onwards like a glacier towards Persia and the borders of Afghanistan and India as the greatest menace the British Empire could be confronted with.” Kolchak’s and Denikin’s struggle for “a reunited Russia,” therefore, was not in Britain’s interest.

According to Denikin, these remarks had a devastating impact on his army, which felt abandoned at a critical time.336 This assessment is confirmed by a British eyewitness:

The effect of Mr. George’s speeches was electrical. Until that moment, the Volunteers and their supporters had comforted themselves with the idea that they were fighting one of the final phases of the Great War, with England still the first of their Allies. Now they suddenly realized with horror that England considered the War as over and the fighting in Russia as merely a civil conflict. In a couple of days the whole atmosphere in South Russia was changed. Whatever firmness of purposes there had previously been, was now so undermined that the worst became possible. Mr. George’s opinion that the Volunteer cause was doomed helped to make that doom almost certain. I read the Russian newspapers carefully every day, and saw how even the most pro-British of them shook at Mr. George’s blows.337

On November 17 the Whites pulled out of Kursk. At this time they learned that three days earlier Kolchak had abandoned Omsk. In mid-December, after Kharkov and Kiev had fallen, their retreat turned into a rout. Territories that had taken months of hard struggle to conquer were given up without a fight. On December 9, in a letter in which he recalled how his warnings had been vindicated, Wrangel wrote Denikin that the “army has ceased to exist as a fighting force.”338

In a reenactment of events in Siberia, mobs of soldiers and civilians, with the Red Cavalry in close pursuit, fled southward toward the Black Sea.

Thousands upon thousands of unhappy people, some of whom had been fleeing for weeks before the advancing Bolshevists, set out again, without friends, without provisions or clothing. It would be senseless to brand these people as rich “bourgeois,” fleeing from a revengeful populace; most of them had no longer a penny in the world, whatever their former fortunes had been, and many of them were working men and peasants who had sampled Bolshevist rule and wished only to escape its second coming.

At one big town in South Russia terrible scenes took place when the town was evacuated. As the last Russian hospital train was preparing to leave one evening, in the dim light of the station lamps some strange figures were seen crawling along the platform. They were gray and shapeless, like big wolves. They came nearer, and with horror it was recognized that they were eight Russian officers ill with typhus, dressed in their grey hospital dressing-gowns, who, rather than be left behind to be tortured and murdered by the Bolshevists, as was likely to be their fate, had crawled along on all fours through the snow from the hospital to the station, hoping to be taken away on a train. Inquiries were made, and it was found (so I was told) that, as usually happened, several hundred officers had been abandoned in the typhus hospitals. The moment the Volunteer Army doctors had left the hospitals, the orderlies had amused themselves by refusing the unhappy officers all attention. What would have happened to them when the mob discovered them is too horrible to be thought of.339

The fleeing masses converged on Novorossiisk, the principal Allied port on the Black Sea, hoping to evacuate on Allied ships. Here, in the midst of a raging typhus epidemic, with the Bolshevik cavalry waiting in the suburbs ready to enter the instant the Allies set sail, terrible scenes were enacted:

The full weight of the human avalanche reached Novorossiisk at the end of March 1920. A non-descript mass of soldiers, deserters, and refugees flooded the city, engulfing the terror-stricken population in a common sea of misery. Typhus reaped a dreadful harvest among the hordes crowding the port. Every one knew that only escape to the Crimea or elsewhere could save this heap of humanity from bloody vengeance when Budenny and his horsemen should take the town; but the amount of shipping available was limited. For several days people fought for a place on the transports. It was a life-and-death struggle.…

On the morning of March 27, Denikin stood on the bridge of the French war vessel, Capitaine Saken, lying in the harbor of Novorossiisk. About him were the vague outlines of transports which were carrying the Russian soldiery to the Crimea. He could see men and women kneeling on the quay, praying to Allied naval officers to take them aboard. Some threw themselves into the sea. The British warship, Empress of India, and the French cruiser, Waldeck-Rousseau, bombarded the roads on which Red cavalry were waiting. Amid horses, camels, wagons, and supplies cluttering the dock were his soldiers and their families with hands raised toward the ships, their voices floating over the waters to nervous commanders, who knew that once their decks were full those who remained on shore must face death or flee where they could. Some fifty thousand were embarked. During the panic and confusion, criminals slunk abroad to prey like ghouls upon the defenseless. Refugees who could not secure passage were compelled to await the grim judgment of Red columns which were already raising dust along roads into the city.

18. Evacuation of White troops on British ships in Novorossiisk, early 1920.

19. Denikin in the Crimea on the day of his resignation.

The same day on which the evacuation occurred, Novorossiisk was occupied by the Bolsheviks and hundreds of White Russians, both civil and military, paid with their lives for resistance to the sickle and hammer of the new regime.340

On arriving at the Crimean port of Sebastopol on April 2, Denikin came under great pressure from disaffected officers to resign. He did so that very day. A poll of senior commanders unanimously elected Wrangel his successor. Wrangel, who had left the army and was living in Constantinople, immediately boarded a British ship bound for the Crimea.

By this time, the Red Army had swept into the Cossack regions, wreaking vengeance. Some Communists called for the wholesale “liquidation” of the Cossacks by “fire and sword.” In anticipation, the Cossacks fled en masse, abandoning their settlements and ill-gotten loot to the outlanders: in some areas their population declined by one-half.341 Ten years later, during collectivization, Cossackdom was abolished.

20. Wrangel.

Wrangel not only had a keen strategic sense, but understood the importance of politics: unlike his predecessors, he realized that in a civil war the combatants were not only armies but also governments, and that in order to win they had to mobilize the civilian population. He surrounded himself with able advisers, among them Peter Struve, whom he entrusted with the conduct of foreign relations, and A. V. Krivoshein, a onetime Minister of Agriculture, whom he placed in charge of domestic affairs, both conservative-liberals. Wrangel devoted much attention to civilian administration and to establishing friendly relations with the non-Russian minorities.342 Even so, his task was hopeless. If he managed to maintain himself in the Crimea for five months it was only because shortly after he had assumed command, the Red Army was distracted by the Polish invasion. In his dual capacity as commander of 100,000–150,000 troops, and the civilian chief of 400,000 refugees who had crowded into the Crimean peninsula, he faced insurmountable difficulties whatever course he chose, evacuation or resumption of the armed struggle.

He could do neither without British help, and this help was denied him. On April 2, as he was leaving Constantinople, the British High Commissioner there handed him a note that called on the Whites to cease forthwith the “unequal struggle”: in return, the British government offered to intercede with Moscow with the view of obtaining for them general amnesty. Their commanding officers were promised asylum in Great Britain. Should the Whites reject the offer, the note warned, the British government would “cease to furnish [them] … with any help or subvention of any kind from that time on.”343