Thermidor” was the month of July in the French revolutionary calendar when Jacobin rule came to an abrupt end, yielding to a more moderate regime. To Marxists the term symbolized the triumph of the counterrevolution, which ultimately led to the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy. It was a development they were determined at all costs to prevent. When, in March 1921, confronting economic collapse and massive rebellions, Lenin felt compelled to make a radical turnabout in economic policy resulting in significant concessions to private enterprise, a course that came to be known as the New Economic Policy (NEP), it was widely believed in the country and abroad that the Russian Revolution, too, had run its course and entered its Thermidorian phase.1

The historical analogy turned out to be inapplicable. The most conspicuous difference between 1794 and 1921 lay in the fact that whereas in France the Jacobins had been overthrown in the Thermidor and their leaders executed, in Russia it was the Soviet equivalent of the Jacobins who initiated and carried out the new, moderate course. They did so on the understanding that the shift was temporary: “I ask you, comrades, to be clear,” said Zinoviev in December 1921, “that the New Economic Policy is only a temporary deviation, a tactical retreat, a clearing of the land for a new and decisive attack of labor against the front of international capitalism.”2 Lenin liked to compare NEP to the Brest-Litovsk treaty, which in its day had also been mistakenly seen as a surrender to German “imperialism” but was only a step backward: however long it would last, it would not be “forever.”3

Secondly, unlike the French Thermidor, the NEP limited liberalization to economics: “As the ruling party,” Trotsky said in 1922, “we can allow the speculator in the economy, but we do not allow him in the political realm.”4 Indeed, in a deliberate effort to prevent the limited capitalism tolerated under the NEP from sliding into a full-scale capitalist restoration, the regime accompanied it with intensified political repression. It was in 1921–23 that Moscow crushed what remained of rival socialist parties, systematized censorship, extended the competence of the secret police, launched a campaign against the church, and tightened controls over domestic and foreign Communists.

The tactical nature of the retreat was not generally understood at the time. Communist purists were outraged by what they saw as the betrayal of the October Revolution, while opponents of the regime sighed with relief that the dreadful experiment was over. During the last two years of his conscious life, Lenin repeatedly had to defend the NEP and insist that the revolution was on course. Deep in his heart, however, he was haunted by a sense of defeat. The attempt to build Communism in a country as backward as Russia, he realized, had been premature, and had to be postponed until the requisite economic and cultural foundations were in place. Nothing went as planned: “The car is out of control,” he let slip once, “a man drives and the car does not go where he steers it, but where it is steered by something illegal, something unlawful, something that comes from God knows where.”5 The internal “enemy,” acting in an environment of economic collapse, confronted his regime with a graver danger than the combined armies of the Whites: “On the economic front, with the attempt of transition to Communism, we have suffered by the spring of 1921 a defeat that was more serious than any inflicted on us by Kolchak, Denikin, or Pilsudski, far more serious, far more basic and dangerous.”6 It was an admission that he had been mistaken in insisting as early as the 1890s that Russia was fully capitalist and ready for socialism.7

Until March 1921, the Communists tried and in some measure succeeded in placing the national economy under state control. Later this policy came to be known as “War Communism”—Lenin himself first used this term in April 1921 as he was abandoning it.8 It was a misnomer coined to justify the disastrous consequences of economic experimentation by the alleged exigencies of the Civil War and foreign intervention. Scrutiny of contemporary records, however, leaves no doubt that these policies were, in fact, not so much emergency responses to war conditions as an attempt as rapidly as possible to construct a Communist society.9 War Communism involved the nationalization of the means of production and most other economic assets, the abolition of private trade, the elimination of money, the subjection of the national economy to a comprehensive plan, and the introduction of forced labor.10

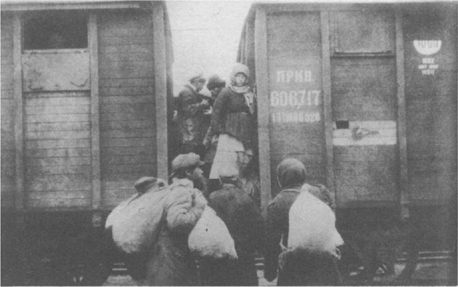

51. Peasant “bag men” peddling grain.

These experiments left Russia’s economy in shambles. In 1920–21, compared to 1913, large-scale industrial production fell by 82 percent, worker productivity by 74 percent, and the production of cereals by 40 percent.11 The cities emptied as their inhabitants fled to the countryside in search of food: Petrograd lost 70 percent of its population, Moscow over 50 percent; the other urban and industrial centers also suffered depletions.12 The nonagricultural labor force dropped to less than half of what it had been when the Bolsheviks took power: from 3.6 to 1.5 million. Workers’ real wages declined to one-third of the level of 1913–14.* A hydralike black market, ineradicable because indispensable, supplied the population with the bulk of consumer goods. Communist policies had succeeded in ruining the world’s fifth-largest economy and depleting the wealth accumulated over centuries of “feudalism” and “capitalism.” A contemporary Communist economist called the economic collapse a calamity “unparalleled in the history of mankind.”13

The Civil War ended, for all practical purposes, in the winter of 1919–20, and if war needs had been the driving force behind these policies, now would have been the time to give them up. Instead, the year that followed the crushing of the White armies saw the wildest economic experiments, such as the “militarization” of labor and the elimination of money. The government persevered with forcible confiscations of peasant food “surplus.” The peasants responded by hoarding, reducing the sown acreage, and selling produce on the black market in defiance of government prohibitions. Since the weather in 1920 happened to be unfavorable, the meager supply of bread dwindled still further. It was now that the Russian countryside, until then relatively well off compared to the cities in terms of food supplies, began to experience the first symptoms of famine.

The repercussions of such mismanagement were not only economic but also social: they eroded still further the thin base of Bolshevik support, turning followers into enemies and enemies into rebels. The “masses,” whom Bolshevik propaganda had been telling that the hardships they had endured in 1918–19 were the fault of the “White Guards” and their foreign backers, expected the end of hostilities to bring back normal conditions. The Civil War had to some extent shielded the Communists from the unpopularity of their policies by making it possible to justify them as militarily necessary. This explanation could no longer be invoked once the Civil War was over:

The people now confidently looked forward to the mitigation of the severe Bolshevik regime. It was expected that with the end of the Civil War the Communists would lighten the burdens, abolish wartime restrictions, introduce some fundamental liberties, and begin the organization of a more normal life.… Most unfortunately, these expectations were doomed to disappointment. The Communist state showed no intention of loosening the yoke.14

It now began to dawn even on those willing to give the Bolsheviks the benefit of the doubt, that they had been had, that the true objective of the new regime was not improving their lot but holding on to power, and that to this end it was prepared to sacrifice their well-being and even their very lives. This realization produced a national rebellion unprecedented in its dimensions and ferocity. The end of one Civil War led immediately to the outbreak of another: having defeated the White armies, the Red Army now had to battle partisan bands, popularly known as “Greens” but labeled by the authorities “bandits,” made up of peasants, deserters, and demobilized soldiers.15

In 1920 and 1921, the Russian countryside from the Black Sea to the Pacific was the scene of uprisings that in numbers involved and territory affected greatly eclipsed the famous peasant rebellions of Stenka Razin and Pugachev under tsarism.16 Its true dimensions cannot even now be established, because the relevant materials have not yet been properly studied. The Communist authorities have assiduously minimized its scope: thus, according to the Cheka, in February 1921, there occurred 118 peasant risings.17 In fact, there were hundreds of such uprisings, involving hundreds of thousands of partisans. Lenin was in receipt of regular reports from this front of the Civil War, which included detailed maps covering the entire country, indicating that vast territories were in rebellion.18 Occasionally, Communist historians give us a glimpse of the dimensions of this other Civil War, conceding that some “bands” of “kulaks” numbered 50,000 and more rebels.19 An idea of the extent and savagery of the fighting can be obtained from official figures of the losses suffered by the Red Army units engaged against the rebels. According to recent information, the number of Red Army casualties in the campaign of 1921–22, which were waged almost exclusively against peasants and other domestic rebels, came to 237,908.20 The losses among the rebels were almost certainly as high and probably much higher.

Russia had known nothing like it, because in the past peasants had traditionally taken up arms against landowners, not against the government. Just as the tsarist authorities had labeled peasant disorders kramola (sedition), so the new authorities called them “banditry.” But resistance was not confined to peasants. More dangerous still, even if less violent, was the hostility of industrial labor. The Bolsheviks had already lost most of the support they had enjoyed among industrial labor in October 1917 by the spring of 1918.21 While fighting the Whites they had managed, with the active help of the Mensheviks and SRs, to rally the workers by playing on the fear of a monarchist restoration. Once the Whites had been defeated, however, and the danger of a restoration no longer existed, the workers abandoned the Bolsheviks in droves, shifting to every conceivable alternative, from the extreme left to the extreme right. In March 1921, Zinoviev told the delegates to the Tenth Party Congress that the mass of workers and peasants belonged to no party, and a good portion of those who were politically active favored the Mensheviks or the Black Hundreds.22 Trotsky was so shocked by the suggestion that, as he interpreted it, “one part of the working class muzzles the remaining 99 percent,” that he asked that Zinoviev’s remarks be struck from the record.23 But the facts were irrefutable: in 1920–21, except for its own cadres, the Bolshevik regime had the whole country against it, and even the cadres were rebelling. Had not Lenin himself described the Bolsheviks as but a drop of water in the nation’s sea?24 And the sea was raging.

They survived this national revolt by a combination of repression, enforced with unrestrained brutality, and concessions embodied in the New Economic Policy. But they also benefited from two objective factors. One was the disunity of the enemy: the second Civil War consisted of a multitude of individual uprisings without a common leadership or program. Flaring up spontaneously, now here, now there, they were no match for the professionally directed and well-equipped Red Army. The other factor was the rebels’ inability to conceive of political alternatives, for neither the striking workers nor the mutinous peasants thought in political terms. The same applied to the numerous “Green” movements.25 A characteristic trait of the peasant mind—an incapacity to conceive government as something capable of being changed—survived the Revolution and all its revolutionary changes.26 The workers and peasants were very unhappy with what the Soviet government did; that there was a connection between what it did and what it was eluded them, exactly as it had under tsarism, when they had turned a deaf ear to radical and liberal agitation. For this reason, now, as then, they could be appeased by having their immediate grievances satisfied while everything else remained in place. This was the essence of the NEP: to purchase political survival with economic handouts that could be taken back once the population had been pacified. Bukharin put it bluntly: “We are making economic concessions to avoid political concessions.”27 It was a practice learned from the tsarist regime, which had protected its autocratic prerogatives by buying off its main potential challenger, the gentry, with economic favors.28

Communism affected the rural population in contradictory ways.29 The distribution to the communes of private land enlarged allotments, and reduced the number of both rich and poor in favor of “middle” peasants, which satisfied the egalitarian propensities of the muzhik. Much of what the peasant had gained, however, he lost to runaway inflation, which robbed him of his savings. He was also subjected to merciless exactions of food “surpluses” and forced to bear numerous labor burdens, of which the duty to cut and cart lumber was the most onerous. Throughout the Civil War, the Bolsheviks waged intermittent warfare on the village, which passively and actively resisted food requisitions.

Culturally, Bolshevism had no influence on the village. The peasants, for whom severity was the hallmark of a true government, respected Communist authority and adapted to it: centuries of serfdom had taught them how to appease and, at the same time, outwit their masters. Angelica Balabanoff noted with surprise “how quickly they had picked up Bolshevik terminology and newly coined phrases and how well they understood the various articles of the new legislation. They seemed to have lived with it all their lives.”30 They adjusted to the new authority as they would to a foreign invader, as their forebears had done under the Tatars. The meaning of the Bolshevik Revolution, the slogans the Bolsheviks propagated, however, remained for them a mystery not worth solving. Investigations by Communist scholars in 1920s found the postrevolutionary village self-contained and closed to outsiders, living, as it always had done, according to its own unwritten rules. Communist presence was hardly visible: such party cells as managed to establish themselves in the countryside were staffed principally with people from the cities. Antonov-Ovseenko, whom Moscow sent in early 1921 to pacify the rebellious Tambov province, in a confidential report to Lenin wrote that the peasants identified Soviet authority with “flying visits by commissars or plenipotentiaries” and food-requisitioning units: they “have become accustomed to viewing the Soviet government as something extraneous, something that does nothing but issue commands, that administers with great zeal but little economic sense.”31

Literate peasants ignored Communist publications, preferring to read religious and escapist literature.32 Only the faintest echoes of foreign events reached the village, and those that did were twisted and misunderstood. The muzhiks showed little interest in who governed Russia, although by 1919 observers noted signs of nostalgia for the old regime.33 Hence it is not surprising that the peasant revolts against the Communists had negative objectives: “[The rebels] aimed not to march on Moscow so much as to cut themselves off from its influence.”*

Rural unrest sputtered throughout 1918 and 1919, forcing Moscow to commit major military forces to contain it. At the height of the Civil War, vast areas of the country were under the control of Green bands, which blended anti-Communist, anti-Jewish, and anti-White sentiments with ordinary brigandage. In 1920 these smoldering fires exploded in a conflagration.

The most violent of the anti-Communist jacqueries broke out in Tambov, a relatively prosperous agricultural province with little industry, 350 kilometers southeast of Moscow.34 Before the Bolshevik coup it had produced up to 60 million puds (one million tons) of grains annually, close to one-third of which was normally shipped abroad. In 1918–1920, Tambov experienced the full brunt of forcible food exactions. This is how Antonov-Ovseenko described the causes behind the outbreak of “banditry” there:

The requisition assessment for 1920–1921, though reduced by half as against that of the year before, proved to be entirely excessive. With huge areas unsown and an exceedingly poor harvest, a considerable part of the province lacked enough bread to feed itself. According to the data of the commissions of experts of the Guberniia Supply Committee there were 4.2 puds of grain per head (after the deduction of seed grain but with no deduction for fodder). In 1909–1913, consumption had averaged … 17.9 puds and, in addition, 7.4 puds of fodder. In other words, in the Tambov province last year the local harvest hardly met one-quarter of the requirements. Under the assessment, the province was to deliver 11 million puds of grain and 11 million puds of potatoes. Had the peasants fulfilled the assessment one hundred percent, they would have been left with 1 pud of grain and 1.6 puds of potatoes per person. Even so, the assessment was fulfilled almost fifty percent. Already by January [1921], half the peasantry was starving.35

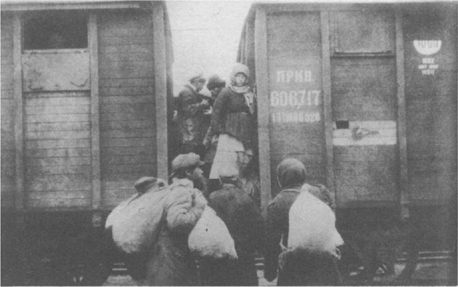

52. Alexander Antonov.

The rebellion broke out spontaneously in August 1920 in a village near the city of Tambov that refused to surrender grain to a requisition team, killed several of its members, and fought off reinforcements.36 In anticipation of a punitive detachment, the village armed itself with such weapons as it had on hand: some guns, but mainly pitchforks and clubs. Villages nearby joined. The rebels emerged victorious from ensuing encounters with the Red Army. Encouraged by their success, the peasants marched on Tambov, their mass swelling as they neared the provincial capital. The Bolsheviks brought in reinforcements, and in September counterattacked, burning rebellious villages and executing captured partisans. The insurrection might have ended then and there had it not been for the appearance of a charismatic leader in the person of Alexander Antonov.

Antonov was a Socialist-Revolutionary, the son of either an artisan or a metal worker, who in 1905–07 had participated in robberies (“expropriations”) organized by his party to replenish its coffers. Caught and convicted, he was sentenced to hard labor in Siberia.37 In 1917 he returned home and joined the Left SRs. Subsequently he collaborated with the Bolsheviks, but broke with them in the summer of 1918 in protest against their agrarian policies. For the next two years, he staged terrorist acts against Bolshevik functionaries, for which he was sentenced to death in absentia. He managed to elude the authorities and soon became a popular hero. He acted on his own with a small band of followers, under SR slogans, although he no longer maintained a connection with that party.

Antonov reappeared in September 1920 and took charge of the peasants, who had lost heart after failing to capture the city of Tambov. An able organizer, he formed partisan units that carried out hit-and-run attacks on collective farms and railway junctions. The authorities proved unable to cope with such tactics not only because the attacks came at the most unexpected places (sometimes Antonov’s men disguised themselves in Red Army uniforms), but because after each such operation the guerrillas returned home and melted into the mass of peasants. Antonov’s followers had no formal program: their purpose was to “smoke out” the Communists from the countryside as they once used to “smoke out” landlords. Here and there, as in all opposition movements of the time, anti-Semitic slogans were heard. The Tambov SRs at this time formed a Union of Toiling Peasants, which produced a platform calling for political equality for all citizens, personal economic liberty, and the denationalization of industry. But it is doubtful that this platform meant anything to the peasants, who really wanted two things only: an end to food requisitions and the freedom to dispose of their surplus. Suspicions have been voiced that the platform was tacked on by SR intellectuals who could not conceive of acting without a formal ideology: “Words came as an afterthought” to deeds.38 Even so, the Union helped the rebels by organizing village committees, which recruited for the partisans.

By the end of 1920, Antonov had up to 8,000 followers, most of them mounted. In early 1921, he went over to conscription, by which means he increased his force to somewhere between 20,000 and 50,000—the number is in dispute. Even at the more modest estimate, it was comparable to the force raised by Russian history’s most famous peasant rebels, Razin and Pugachev. Patterned on the Red Army, it was divided into 18 or 20 “regiments.”39 Antonov organized good intelligence and communications networks, assigned political commissars to combat units, and enforced strict discipline. He continued to avoid direct encounters, preferring quick surprise raids. The center of his rebellion was the southeastern part of Tambov province, but it spilled over, without igniting comparable risings, into the adjoining provinces of Voronezh, Saratov, and Penza.40 Antonov succeeded in cutting the railroad line that carried the confiscated grain to the center; such grain as he did not need, he distributed to peasants.41 In areas under his control, he abolished Communist institutions and killed captured Communists, often after brutal tortures: the number of his victims is said to have exceeded one thousand. By such methods he managed to sweep from large areas of Tambov province all traces of Communist authority. His ambitions were grander, however, for he issued appeals to the Russian people to join him and march on Moscow to liberate the country from its oppressors.42

53. Captured Antonov partisans.

Moscow’s initial reaction (August 1920) was to place the province under a state of siege. In public pronouncements, the government described the rebels as “bandits” acting at the behest of the SR Party. It knew better: in internal communications, Communist officials conceded that the uprising was of spontaneous origin and ignited by resistance to requisition teams. Although many local SRs did offer support, the central organs of the party repudiated any connection with the rebellion: the SR Organization Bureau described it as a “semi-bandit movement,” and the party’s Central Committee forbade its members to have any dealings with it.43 The Cheka, however, used the Tambov uprising as a pretext for arresting every SR activist it could lay its hands on.

When it became apparent that the regular army could not cope, Moscow delegated Antonov-Ovseenko to Tambov in late February 1921 to head a plenipotentiary commission. Endowed with broad discretionary powers, he was instructed to report directly to Lenin. But success eluded him as well, in good measure because many Red Army soldiers under his command, mostly peasant conscripts, sympathized with the rebels. It became apparent that the only way to quell the disorders was to strike at the rebels’ civilian supporters in order to isolate them, and this required resort to unrestricted terror: concentration camps, executions of hostages, mass deportations. Antonov-Ovseenko requested and obtained Moscow’s authorization to employ such measures.44

During the winter of 1920–21, the food and fuel supply situation in the cities of European Russia recalled that on the eve of the February Revolution. The breakdown of transport and peasant hoarding caused a precipitous fall in deliveries; Petrograd, due to its remoteness from the producing areas, once again suffered the most. Factories closed for lack of fuel; more inhabitants fled the city. Those who stayed headed for the countryside to barter for food manufactured goods issued them gratis by the government or stolen from places of work, only to be stopped on their way back by “barring detachments” (zagraditel’nye otriady) that confiscated the produce.

It was against this background that in February 1921 the sailors of Kronshtadt, Trotsky’s “beauty and pride of the Revolution,” raised the banner of revolt.

The spark that ignited the naval mutiny was a government order of January 22 reducing by one-third the bread ration in a number of cities, including Moscow and Petrograd, for a period of ten days.45 The measure was necessitated by shortages of fuel, which had shut down several railroad lines.46 The first protests erupted in Moscow. A conference of partyless metallurgical workers of the Moscow region at the beginning of February heard sweeping denunciations of the economic policy of the regime, demands for the abolition of “privileged” rations for all, including members of the Sovnarkom, and for the replacement of random food exactions with a regular tax in kind. Some speakers called for the convocation of a Constituent Assembly. On February 23–25 many Moscow workers went on strike, demanding that they be allowed to obtain food on their own, outside the official rationing system.47 These protests were quelled by force.

Disaffection spread to Petrograd, where food rations for industrial workers, the most privileged caste, had been reduced to 1,000 calories a day. In early February 1921, some of the largest enterprises there were forced to shut down for lack of fuel.48 From February 9, sporadic strikes broke out: the Petrograd Cheka determined that their cause was exclusively economic, there being no evidence of “counterrevolutionary” involvement.49 From February 23 on, workers held meetings, some of which ended in walkouts. Initially, the Petrograd workers demanded only the right to scour the countryside for food, but before long, probably under Menshevik and SR influence, they added political demands calling for honest elections to the soviets, freedom of speech, and an end to police terror. Here, too, anti-Communist sentiments were occasionally accompanied by anti-Semitic slogans. At the end of February, Petrograd faced the prospect of a general strike. To avert it, the Cheka proceeded to arrest all leading Mensheviks and SRs in the city, a total of 300. Zinoviev’s attempt to calm the rebellious workers was unsuccessful: his audiences were hostile and prevented him from speaking.50

Confronted with worker defiance, Lenin reacted exactly as had Nicholas II four years earlier: he turned to the military. But whereas the last tsar, weary and unwilling to fight, soon caved in, Lenin was prepared to go to any length to stay in power. On February 24, the Petrograd Committee of the Communist Party formed a “Defense Committee”—“defense” from whom was not specified—that in words reminiscent of General S.S. Khabalov’s orders of February 25–26, 1917, proclaimed a state of emergency and prohibited all street gatherings. The committee was chaired by Zinoviev, whom the anarchist Alexander Berkman called “the most hated man in Petrograd.” Berkman heard a speech by a member of this group, the Bolshevik M. M. Lashevich, looking “fat, greasy and offensively sensuous,” who dismissed the protesting workers as “leeches attempting extortion.”51 The striking workers were locked out, which had the effect of depriving them of food rations. The authorities kept on arresting Mensheviks, SRs, and anarchists in Petrograd and in other parts of the country to keep them away from the rebellious “masses.” Whereas in February 1917, the main source of disaffection had been the garrison, now it was the factory. Even so, the Red Army units stationed in Petrograd gave cause for concern, since some of them declared they would not take part in suppressing worker demonstrators. These units were disarmed.

News of labor unrest in Petrograd reached the naval base of Kronshtadt. The 10,000 sailors stationed there had traditionally shown a preference for anarchism of no particular ideological orientation, dominated by hatred of the “bourgeoisie.” In 1917, these sentiments had served the Bolsheviks; now they turned against them. Bolshevik support at the naval base began to erode soon after October, and although in 1919 the sailors had fought valiantly for the Reds in the defense of Petrograd, they were far from enthusiastic about the regime, especially after the Civil War was over.52 In the fall and winter of 1920–21, half the members of the Kronshtadt Party organization, numbering 4,000, turned in their cards.53 When rumors spread that striking workers in Petrograd had been fired upon, a delegation of sailors was sent to investigate: on its return it reported that workers on the mainland were treated as they once were in tsarist prisons. On February 28, the crew of the battleship Petropavlovsk, previously a Bolshevik stronghold, passed an anti-Communist resolution. It called for the reelection of soviets by secret vote, freedom of speech and press (but only “for workers and peasants, anarchists, and left socialist parties”), freedom of assembly and trade unions, and the right of peasants to cultivate their land as they saw fit provided they did not employ hired labor.54 The following day the resolution was adopted with near-unanimity by an assembly of sailors and soldiers in the presence of Kalinin, who had been sent to pacify the mutineers. Many Communists present at the rally voted for the resolution. On March 2, the sailors formed a Provisional Revolutionary Committee to take charge of the island and organize its defense against the anticipated assault from the mainland. The rebels had no illusions about their ability to withstand for long the might of the Red Army, but they counted on rallying the nation and the armed forces to their cause.

54. A typical street scene under War Communism.

55. Muscovites destroying houses for fuel.

In this expectation they were disappointed, for the Bolsheviks took prompt and effective countermeasures to prevent the mutiny’s spread: in this respect, the new totalitarian regime proved far more competent than tsarism. The sailors found themselves isolated, and locked in a military struggle they could not possibly win.

It is interesting to observe how quickly the Bolsheviks assimilated the habit of the old regime of attributing any challenge to their authority to dark, foreign forces. Then they had been the Jews; now they were “White Guardists.” On March 2, Lenin and Trotsky declared the mutiny to be a plot of “White Guard” generals, behind whom stood the SRs and “French counterintelligence.”* To keep the Kronshtadt mutiny from contaminating Petrograd, the Defense Committee ordered troops to disperse crowds and to fire if disobeyed. The repressive measures were coupled with concessions: Zinoviev withdrew the “barring detachments” and dropped hints that the government was about to abandon food requisitioning. The combination of force and concessions mollified the workers, depriving the sailors of vital support.

One week after the outbreak of the Kronshtadt mutiny, the Bolshevik leadership gathered in Moscow for the Tenth Party Congress. Although it was on everyone’s mind, the mutiny was not on the agenda. In his address, Lenin made light of it, dismissing it as a counterrevolutionary plot: the involvement of “White generals” had been “fully proven,” he declared, and the whole conspiracy had been hatched in Paris.55 In reality, the leadership took this challenge very seriously.

Trotsky arrived in Petrograd on March 5. He ordered the mutineers to surrender at once and to throw themselves on the mercy of the government; the alternative was military retribution.56 With minor changes, his ultimatum could have been issued by a tsarist governor-general. One appeal to the rebels threatened that if they continued resistance they would be “shot like partridges.”57 Trotsky ordered the mutineers’ wives and children residing in Petrograd to be taken hostage.58 Annoyed with the insistence of the head of the Petrograd Cheka that the Kronshtadt rebellion was “spontaneous,” he asked Moscow to have him dismissed.59

Upon learning of Trotsky’s actions, the defiant Kronshtadt mutineers recalled the order to the security forces on Bloody Sunday in 1905, attributed to the governor of St. Petersburg, Dmitrii Trepov—“Don’t spare bullets.” The “toilers’ revolution,” the rebels vowed, will “sweep from the face of Soviet Russia, stained by their actions, the vile slanderers and aggressors.”60

Kronshtadt is an island, which at any other season than winter would have been very difficult to capture by force: but in March, the waters surrounding it were still solidly frozen. This fact facilitated the onslaught, the more so that the rebellious sailors ignored the advice of their officers to break up the ice with artillery. On March 7, Trotsky ordered the assault to begin. The Red forces were under the command of Tukhachevskii. In view of the undependability of the regular troops,61 Tukhachevskii interspersed in their midst units from special elite divisions formed to combat internal resistance.*

The attack, launched from a base northwest of Petrograd, began in the morning of March 7 with an artillery barrage from mainland batteries. That night, Red troops wrapped in white sheets stepped onto the ice and ran toward the naval base. In their rear were deployed Cheka machine-gun detachments with orders to shoot any soldiers who retreated. The assault turned into a rout as the attackers were cut down by machine-gun fire from the naval base. Some Red soldiers refused to charge; about one thousand went over to the rebels. Trotsky ordered the execution of every fifth soldier who disobeyed orders.

The day after the first shots had been fired, the Izvestiia of the Provisional Revolutionary Committee of Kronshtadt published a programmatic statement, “What we are fighting for,” calling for a “Third Revolution.” The document, anarchist in spirit, bears all the hallmarks of having been written by an intellectual, but that it expressed the sentiments of the defendants is proven by their willingness to fight and die for it.

In carrying out the October Revolution, the working class hoped to achieve its liberation. The outcome has been even greater enslavement of human beings.

Power has passed from a monarchy based on the police and gendarmerie into the hands of usurpers—Communists—who have given the toilers not freedom but the daily dread of ending up in the torture chambers of the Cheka, the horrors of which exceed many times the rule of tsarism’s gendarmerie.

The bayonets, the bullets, the coarse shouts of the oprichniki† from the Cheka—this is the fruit of the long struggles and sufferings of Soviet Russia’s toilers. The glorious emblem of the toilers’ state—the hammer and sickle—Communist authority has in truth replaced with the bayonet and the iron bar, created to protect the tranquil and careless life of the new bureaucracy, the Communist commissars and functionaries.

56. Red Army troops assaulting Kronshtadt.

But basest and most criminal of all is the moral slavery introduced by the Communists: they have also laid their hands on the inner world of the working people, compelling them to think only as they do.

By means of state-run trade unions, the workers have been chained to their machines, so that labor is not a source of joy but a new serfdom. To the protests of peasants, expressed in spontaneous uprisings, and those of the workers, whom the very conditions of life compel to strike, they have responded with mass executions and an appetite for blood that by far exceeds that of tsarist generals.

Toiling Russia, the first to raise the red banner of the liberation of labor, is thoroughly drenched with the blood of the victims of Communist rule. In this sea of blood, the Communists drown all the great and bright pledges and slogans of the toilers’ revolution.

It has become ever more clear, and by now it is self-evident, that the Russian Communist Party is not the protector of the working people that it claims to be, that the interests of the working people are foreign to it, and that, having gained power, its only fear is of losing it, and hence that all means [to that end] are permissible: slander, violence, deception, murder, revenge on the families of those who have revolted.

The long suffering of the toilers has drawn to an end.

Here and there the red glow of revolt against oppression and coercion is lighting up the country’s sky.…

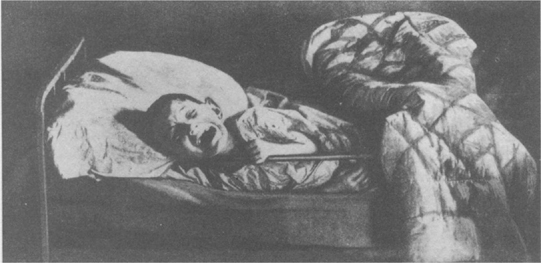

57. After the assault.

The current revolt finally offers the toilers a chance to have their freely elected, functioning soviets, free of violent party pressures, to refashion the state-run trade unions into free associations of workers, peasants, and the working intelligentsia. At last, the police baton of Communist autocracy is smashed.62

During the week that followed, Tukhachevskii assembled reinforcements, all the while keeping the defenders off balance with nightly raids. The morale on the island declined from the lack of mainland support and the depletion of food supplies. The Red command was apprised of this fact by Kronshtadt Communists, whom the rebels allowed freedom of movement and access to telephones. To keep up the spirit of their own troops, reluctant to attack their comrades, the Communists initiated an intense propaganda effort that depicted the rebels as witless tools of the counterrevolution.

The final assault by 50,000 Red troops began during the night of March 16–17: this time, the main Red force charged from the south, from Oranienbaum and Peterhof. The defenders numbered 12,000–14,000, of whom 10,000 were sailors, and the rest infantry. The attackers managed to creep up close to the island before being noticed. Ferocious fighting ensued, much of it hand to hand. By the morning of March 18, the island was under Communist control. Several hundred prisoners were slaughtered. Some of the defeated rebels, leaders included, managed to save themselves by fleeing across the ice to Finland, where they were interned. It was the intention of the Cheka to distribute the surviving prisoners in the Crimea and the Caucasus, but Lenin told Dzerzhinskii that “it would be more convenient” to have them concentrated “somewhere in the north.”63 This meant isolation in the most savage concentration camps on the White Sea, from which few ever emerged alive.

The crushing of the Kronshtadt uprising was not well received by the population. It did not enhance the reputation of Trotsky: although he loved to dwell on his military and political triumphs, in his memoirs he omitted any mention of his role in this tragic event.

Lenin and Trotsky received regular reports from the field staff of the Revolutionary-Military Council about combat operations against the “bands” operating in Tambov, as if it were a regular war front.64 Although the staff reported one victory after another, now scattering, now pulverizing the rebels, it was evident that this enemy, waging highly unconventional warfare, could not be defeated by conventional military means. Lenin, therefore, decided to call on Tukhachevskii to mount a decisive campaign.65 Arriving in Tambov at the beginning of May, Tukhachevskii assembled a force which at the height of the operation numbered over 100,000 men.66 Assisting the Red Army were “International Units” of Hungarian and Chinese volunteers. Tukhachevskii realized that he confronted not only a military force—thousands of guerrillas—but also a hostile population of millions. Reporting to Lenin after he had broken the back of the insurrection, he explained that the struggle “had to be regarded not as some kind of more or less protracted operation but as an entire campaign and even war.”67 “Our supreme command decided not to be captivated by punitive measures but to conduct a regular campaign,” explained another Bolshevik. “It was decided to conduct all operations in a cruel manner so that the very nature of the actions [taken] would command respect.”68 Tukhachevskii’s strategy was to conquer the territory methodically, so as to separate the partisans from the civilian population that supplied them with recruits and provided other forms of assistance.69 Since conquering and occupying a whole province exceeded the capabilities of the force assigned to the mission, Tukhachevskii relied on “cruelty,” that is, exemplary terror.

Essential to this strategy was good intelligence. Using paid informers, the Cheka obtained lists of the partisans: a special directive (No. 130), issued by Antonov-Ovseenko’s commission, ordered their families to be held as hostages. Using these lists, to which it added the names of peasants designated “kulaks,” the Cheka herded thousands of hostages into concentration camps especially built for the purpose. Areas of particularly intensive partisan activity were singled out for what official documents referred to as “massive terror.” According to Antonov-Ovseenko’s report to Lenin, to break the silence of the inhabitants, Red commanders used the following procedures:

A special “sentence” is pronounced on these villages which enumerates their crimes against the laboring people. The entire male population is placed under the jurisdiction of the Revolutionary Military Tribunal; all the families of bandits are removed to a concentration camp to serve as hostages for the relative belonging to a band; a term of two weeks is given the bandit to give himself up, at the end of which the family is deported from the province and its property (until then sequestered conditionally) is confiscated for good.70

Savage as they were, these measures still did not produce the desired results, because the partisans retaliated by taking hostage and executing families of Red Army soldiers and Communist officials, often in a very sadistic manner.71 Antonov-Ovseenko’s commission therefore issued another directive on June 11 (No. 171), which raised still higher the level of terror by ordering the execution without legal formalities of numerous categories of offenders:

As a result of these orders, hundreds, if not thousands, of peasants were killed: liable to execution, as later under Nazi rule, were persons whose only crime was giving refuge to the abandoned children of “bandits.”73 In many villages, hostages were executed in batches. According to Antonov-Ovseenko, in “the second most pro-bandit uezd,” 154 “bandit hostages” were shot, 227 families of “bandits” taken hostage, 17 houses burned, 24 pulled down, and 22 turned over to the “village poor” (a euphemism for collaborators).74 In instances of particularly stubborn resistance, entire villages were “relocated” to neighboring provinces. Lenin not only approved of these measures but instructed Trotsky to make certain that they were accurately implemented.75

Tukhachevskii’s campaign got underway in late May 1921. He had been authorized to resort to poison gas against the rebels and lost no time warning them that he meant to use it:

Members of White Guard bands, partisans, bandits, surrender! Otherwise, you will be mercilessly exterminated. Your families and your belongings have been taken hostage for you. Hide in the village—you will be turned over by your neighbors. If anyone gives shelter to your family, he will be shot and his family arrested. If you hide in the woods—we will smoke you out. The Plenipotentiary Commission has decided to use asphyxiating gas to smoke the bands out of the forests.…76

Ten days later Antonov’s army was surrounded and destroyed, but Antonov himself managed to escape. Another guerrilla army loyal to him held out for a couple of weeks. Eventually, all that remained of his once formidable force were small partisan detachments that carried out desultory raids. The population, terrorized, but also mollified by the abandonment of food exactions in March 1921, withdrew support of the rebels. The next year, 1922, was a good one for Russian peasants: the crops were abundant and the taxes reasonable.

Forsaken by all, Antonov became a hunted quarry. The end came on June 24, 1922: betrayed by his onetime supporters, he was tracked down and killed by the GPU. It is said that the peasants welcomed his death, cursing his body as it was borne through their villages to Tambov and cheering his killers.77 But then, the entire incident may well have been staged.

The remarkable success of guerrilla leaders like Antonov in standing up to the regular army made a deep impression on the Soviet High Command. M. V. Frunze, the Red Army’s Chief of Staff and later Trotsky’s successor as Commissar of War, ordered studies to be undertaken of unconventional warfare for future use against a technically superior enemy.78 On the basis of these investigations, the Red Army would resort to partisan warfare on a large scale against the invading Nazis. And the Nazi command, in turn, would replicate the methods of terror against the civilian population which the Red Army had developed in 1921–22 in its campaign against peasant guerrillas.

The need to pacify the peasantry became apparent to Lenin even before Kronshtadt: the matter was discussed in the Politburo in February 1921. The event that may have prompted these deliberations was the peasant uprising in western Siberia that broke out on February 9.79 The partisans, numbering in the tens of thousands, occupied several major towns, including Tobolsk, and cut the railroad line linking central Russia with eastern Siberia. With local forces unable to cope, the Center mobilized 50,000 troops in the area.80 In intense battles, the regular army eventually succeeded in suppressing the guerrillas. But the two-week disruption of food shipments from Siberia was a calamity that compelled the Soviet leaders, while the uprising was still in progress, to rethink their whole agrarian policy.81

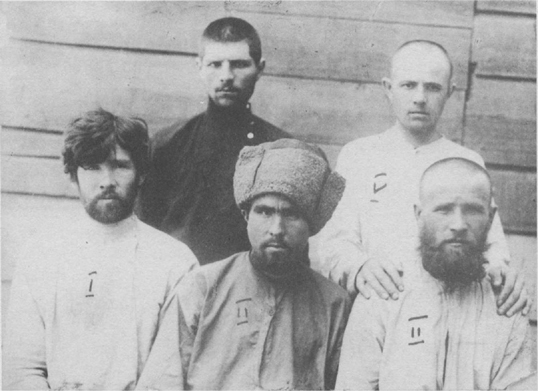

58. A “food detachment” about to depart for the village.

The sailors’ mutiny finally forced their hand: it was on March 15, as the Red Army stood poised to launch the final assault on the naval base, that Lenin announced what was to become the linchpin of the New Economic Policy, the abandonment of arbitrary food confiscation known as prodrazvërstka in favor of a tax in kind. Prodrazvërstka had been the most universally despised feature of “War Communism”—despised by peasants, whom it robbed of their produce, but also by the urban population, whom it deprived of food.

Requisitioning had been enforced in an appallingly arbitrary manner. The Commissariat of Supply determined the quantity of foodstuffs it required—a quantity determined by what was needed to feed the consumers in the cities and the armed forces, without regard to what the producers could provide. This figure it broke down, on the basis of inadequate and often outdated information, into quotas for each province, district, and village. The system was as inefficient as it was brutal: in 1920, for example, Moscow set the prodrazvërstka at 583 million puds (9.5 million tons) but managed to collect only half that amount.82

Collectors acted on the premise that peasants lied when they claimed that the grain they were forced to surrender was not surplus but essential to provide food for their families and seed, and that they could compensate for the loss by digging up their hoard. This the peasants may have been able to do in 1918 and 1919. But by 1920 they had little if anything left to hoard: as a result, as we have seen in the case of Tambov province, prodrazvërstka, even if incompletely realized, left them with next to nothing. Nor was this all. Zealous collectors impounded not only “surplus” and food needed for sustenance, but grain set aside for the next season’s sowing: one high Communist official admitted that in many areas the authorities appropriated one hundred percent of the harvest.* Refusal to pay resulted in the confiscation of livestock and beatings. In addition, collecting agents and local officials, empowered to label resistance to their demands as “kulak”-inspired or “counterrevolutionary,” felt at liberty to appropriate food, cattle, even clothing for their personal use.83 The peasants resisted fiercely: in the Ukraine alone, they were reported to have killed 1,700 requisition officials.84

A more self-defeating policy would be hard to conceive. The system operated on the absurd principle that the more the peasant produced the more would be taken from him; from which it followed with inexorable logic that he would produce little if anything beyond his own needs. The richer a region, the more it was subjected to government plunder, and the more prone it was to curtail production: between 1916–17 and 1920–21, the decline in the sown acreage in the center of the country, an area of grain deficits, was 18 percent, whereas in the main region of grain surpluses it was 33 percent.† And since yields per acre declined from shortage of fertilizer and draft animals as well, grain production, which in 1913 had been 80.1 million tons, dropped in 1920 to 46.1 million-tons.85 If in 1918 and 1919 it had still been possible to extract a “surplus,” by 1920 the peasant had learned his lesson and made sure there was nothing to surrender. It apparently never occurred to him that the regime would take what it wanted even if it meant that he went breadless and seedless.

Prodrazvërstka had to be abandoned for both economic and political reasons. There was nothing left to take from the peasant, who faced starvation; and it fueled nationwide rebellions. The Politburo finally decided to drop prodrazvërstka on March 15.* The new policy was made public on March 23.86 Henceforth, the peasants were required to turn over to government agencies a fixed amount of grain; arbitrary confiscations of “surplus” were terminated.

In announcing the new policy, Lenin emphasized its political significance: in Russia, where the peasantry constituted the vast majority of the population, one could not govern effectively without its support. In an internal communication, Kamenev listed “introducing political tranquillity to the peasantry” as the policy’s first objective (followed by encouraging increases in the sown acreage).87 Previously viewed as a class enemy, the peasant was henceforth to be treated as an ally. Lenin now acknowledged a fact that had eluded him earlier, namely that in Russia, in contrast to much of Western Europe, the majority of rural inhabitants were neither hired hands nor tenants but independent small producers.88 To be sure, the latter were a “petty bourgeoisie,” and concessions to them were a regrettable retreat, but it was temporary: Lenin justified it as an “economic breathing spell,” while Bukharin and D. B. Riazanov spoke of a “peasant Brest [-Litovsk].”89 How long the “breathing spell” would last was left unsaid, but at one point Lenin conceded that “transforming” the peasant could take generations.90 These and other remarks of Lenin’s on the subject suggest that although collectivization remained his ultimate objective, he would not have launched it as early as did Stalin.

As spelled out in April 1921, the new policy imposed on peasant households a standard tax in grain, potatoes, and oil-yielding seeds. Later that year, other agricultural products were added to the list: eggs and dairy products, wool, tobacco, hay, fruits, honey, meat, and raw leather.91 The size of the grain tax was determined by the minimal requirements of the Red Army, industrial workers, and other nonagricultural groups. Its allocation, left to the discretion of village soviets, was to be commensurate with the ability of a given household to pay, as determined by its size, the quantity of arable land at its disposal, and local grain yields. To encourage the peasants to increase their output, the decree based the amount of land subject to the tax not on that actually under cultivation but on that capable of being cultivated, that is, the total arable. The principle of “collective responsibility” (krugovaia otvetstvennost’) for meeting state obligations was abandoned.92

The first tax in kind was set at 240 million puds, 60 million less than obtained in 1920 and only 41 percent of the prodrazvërstka quota previously set for 1921. The government hoped to make up for the shortfall by offering the peasant, on a barter basis, manufactured goods for his surplus grain: this was to bring in an additional 160 million puds.93 None of these expectations was met because of the severe drought that struck the principal grain-producing areas in the spring of 1921: since the afflicted areas provided next to nothing, instead of 240 million puds, the tax brought in only 128 million.94 Nor did the proposed exchange bring in any grain, because there were no manufactured goods to barter.

Although the new policy resulted in no immediate improvement—indeed, initially it yielded less food than prodrazvërstka—it marked a significant advance in Communist thinking that in the longer run was to prove highly beneficial. For in contrast to past practices that treated peasants as mere objects of exploitation, the tax in kind, or prodnalog, also took their interests into account.

While the economic benefits of the new agrarian policy were not immediately apparent, the political rewards were reaped at once. The abandonment of food requisitioning took the wind out of the sails of rebellion. The following year, Lenin could boast that peasant uprisings, which previously had “determined the general picture of Russia,” had virtually ceased.*

When they introduced the tax in kind, the Bolsheviks had no idea of its ramifications, for they meant to keep intact the centralized management of the national economy: the last thing they wanted was to abandon the state monopoly on trade and manufacture. They fully expected to absorb the grain surplus by giving the peasant manufactured goods in exchange. It soon became evident, however, that the expectation was unrealistic, in consequence of which, they were compelled, step by step, to carry out ever more ambitious reforms that in the end produced the unique hybrid of socialism and capitalism known as the New Economic Policy. (The term first became current in the winter of 1921–22.)95 The tax in kind

necessarily implied the restoration for the peasantry of the right to trade in that part of the surplus produce which remained at their disposal (otherwise the leaving of this surplus at their disposal would have been no more than a nominal concession, possessing very little influence as an incentive to increase peasant production). This in turn implied the revival of a market in agricultural produce, the recreation of market relations as an essential link between agriculture and industry, and a restored sphere of circulation for money.96

Prodnalog thus unavoidably led, in the first place, to the restoration of private trade in grain and other foodstuffs—this barely fifteen months after Lenin had sworn that he would rather have everyone die than relinquish the state monopoly on the grain trade.97 It further meant a return to conventional monetary practices, with a stable currency backed by objects of acknowledged value. It also implied the abandonment of the state monopoly on industry, since the peasant was likely to part with his surplus only if he could obtain for it manufactured goods: this, in turn, required privatizing a good part of the consumer industry. In this manner, an emergency measure designed to quell a nationwide uprising against them led the Communists into uncharted waters that could end in the restoration of capitalism and its corollary, “bourgeois democracy.”*

Between 1922 and 1924, Moscow abandoned the ideal of a moneyless economy and adopted orthodox fiscal practices. The transition to fiscal responsibility was difficult because the government required mountains of paper money to cover budgetary deficits. In the first three years of the NEP, the Soviet Union had, in effect, two currencies circulating side by side: one, the virtually worthless “tokens” known as denznaki or sovznaki; the other, a new gold-based ruble called a chervonets.

Paper rubles were produced as rapidly as the printing presses would allow. In 1921, the issuance was 16 trillion; in 1922, it rose to nearly two quadrillion: “An amount that has sixteen places and that under brighter economic skies is associated with astronomy rather than with finance.”98 The peasants refused paper tokens and used commodities, mainly grain, as a medium of exchange.

While continuing to flood the country with worthless paper, the government took steps to create a new, stable currency. Fiscal reform was entrusted to Nicholas Kutler, a banker and a minister in Sergei Witte’s cabinet, and, following his retirement from government service, a Kadet Duma deputy. Kutler was appointed to the board of the State Bank (Gosbank), which was brought into being in October 1921 on his recommendation. It was also on his advice that the regime issued the new currency, and denominated the state budget in tsarist rubles.99 (Two years later, a similar reform would be carried out in Germany under the aegis of Hjalmar Schacht.) In November 1922, the State Bank was authorized to issue chervontsy, banknotes in five denominations, backed 25 percent by bullion and foreign reserves, and the rest by commodities and short-term obligations: each new ruble represented 7.7 grams of pure gold, the gold equivalent of 10 tsarist rubles.† Chervontsy, intended for large-scale transactions and settlements between state enterprises rather than as legal tender, nevertheless circulated alongside the old tokens, which despite their astronomical denominations were needed for small retail transactions. (Lenin, embarrassed by having to restore gold to its traditional place in monetary policy, promised that as soon as Communism triumphed globally its use would be confined to the building of lavatories.100) By February 1924, nine-tenths of all accounts were denominated in chervontsy.101 In February 1924, token rubles were withdrawn from circulation and replaced with “State Treasury Notes” with the gold content of one tsarist ruble. At this time, peasants were permitted to meet their state obligations partly or wholly in money rather than produce.

The tax system, too, was reformed along traditional lines. The state budget, calculated in gold rubles, was regularized. The deficit, which in 1922 amounted to more than half of the outlays, gradually narrowed. Laws issued in 1924 prohibited the issuance of banknotes as a device for covering deficits.102

Despite resistance from managers of the nationalized enterprises, decrees were passed encouraging small-scale private and cooperative industries, which were accorded the status of juridical persons and allowed to employ a limited number of salaried workers. Large enterprises remained in the state’s hands and continued to benefit from government subsidies. Well aware that the NEP risked eroding the socialist foundations of the state, and, with it, his power base, Lenin made certain that the government retained control over the “commanding heights” of the economy: banking, heavy industry, and foreign trade,103 as well as transport. Middle-sized enterprises were ordered to follow sound accounting practices and to become self-supporting, a practice known as khozrazchët. Those that were either idle or unproductive were designated as primary candidates for leasing:104 over 4,000 such enterprises, a high proportion of them flour mills, were leased either to their previous owners or to cooperatives.105 These concessions were mainly significant in the principles they established, especially in allowing hired labor, a practice socialists regarded with utmost repugnance. Their effect on production was limited. In 1922, state enterprises accounted for 92.4 percent of the nation’s industrial output as measured by value.106

The transition to khozrazchët forced the abandonment of the elaborate structure of free services and goods, by virtue of which in the winter of 1920–21 the basic needs of some 38 million citizens had been provided at government expense.107 Postal services and transportation were to be paid for. Workers received money wages and had to purchase whatever they needed on the open market. Rationing, too, was gradually eliminated. Step by step, retail trade was privatized. Citizens were permitted to deal in urban real estate, to own publishing firms, to manufacture pharmaceuticals and agricultural implements. The right of inheritance, abolished in 1918, was partially restored.108

The NEP bred an unattractive type of entrepreneur, very unlike the classic “bourgeois.”109 The environment for private enterprise in the Soviet Union was basically so unfriendly, and its future so uncertain, that those who took advantage of economic liberalization spent their profits without thought for tomorrow. Treated as pariahs by government and society alike, the “nepmen” repaid them in kind. Living lavishly and conspicuously in the midst of poverty, they crowded expensive restaurants and nightclubs, flaunting their fur-wrapped mistresses.

59. The Sukharevka Market in Moscow, center of the black market under War Communism and retail trade—under the NEP.

The aggregate results of the measures subsumed under the fully developed New Economic Policy were undoubtedly beneficial, although unevenly so. Just how beneficial it is difficult to determine, for Soviet economic statistics are notoriously unreliable, differing, depending on the source one employs, by as much as several hundred percent.*

The benefits appeared first and foremost in agriculture. In 1922, thanks to donations and purchases of seed grain abroad as well as favorable weather, Russia enjoyed a bumper crop. Encouraged by the new tax policy to increase the cultivated acreage, peasants expanded production: the acreage sown in 1925 equaled that of 1913.110 Yields, however, remained lower than before the Revolution, and the harvest proportionately smaller: as late as 1928, on the eve of collectivization, it was 10 percent below the 1913 figure.

Industrial production grew more slowly due to shortages of capital, obsolescence of equipment, and similar causes that defied quick remedies. The foreign concessions on which Lenin had counted to boost production amounted to little because foreigners hesitated to invest in a country that had defaulted on loans and nationalized assets. The Soviet bureaucracy, hostile to foreign capital, did all in its power to obstruct concessions by resort to red tape and other forms of chicanery. And the Cheka, and later the GPU, did their part by treating all foreign economic involvement in Russia as a pretext for espionage. In the final year of NEP (1928) there were only 31 functioning foreign enterprises in the Soviet Union, with a capital (in 1925) of a mere 32 million rubles (16 million dollars). The majority of these enterprises engaged not in manufacturing but the exploitation of Russia’s natural resources, especially timber: the latter accounted for 85 percent of the foreign capital invested in concessions.111

60. A Moscow produce market under the NEP.

The NEP precluded comprehensive economic planning, which the Bolsheviks regarded as essential to socialism. The Supreme Council of the National Economy gave up any idea of organizing the economy and concentrated on managing, as best it could, Russia’s virtually inoperative industries by means of “trusts.” The trusts received from the state financial as well as material subsidies; other materials they were free to purchase on the open market. After their costs were covered, their entire production was turned over to the government. For purposes of economic planning Lenin created in February 1921 a new agency, popularly known as Gosplan, whose immediate task was to carry out a gigantic program of electrification that would provide the basis for future industrial and socialist development. Even before the NEP, in 1920, Lenin had created a State Commission for the Electrification of Russia (GOELRO), which he expected over the next 10 to 15 years vastly to expand the electric power capacity of the country, mainly by developing hydroelectric energy. He entertained fantastic expectations of this project’s ability to solve problems that had defied other solutions. The hope found expression in his celebrated slogan, whose precise meaning remains elusive to this day, “The soviets plus electrification equal Communism.”112 In the resolutions of the Twelfth Party Congress (1923), electrification was described as the central focus of economic planning and the “keystone” of the country’s economic future. For Lenin its implications were grander still. He genuinely believed that the spread of electric power would destroy the capitalist spirit in its last surviving bastion, the peasant household, and undermine religious belief: Simon Liberman heard him say that for the peasant, electricity will replace God and that he will pray to it.113

The entire program was but another Utopian scheme that ignored costs and came to naught for lack of money: for it soon became apparent that it required annual outlays of one billion gold rubles (500 million dollars) over a period of 10 to 15 years. “Given the fact that the nation’s industry was virtually at a standstill,” writes a Russian historian, “and that there were no exports of grain for the purchase abroad of the necessary equipment and technical specifications, the program of electrification in reality resembled ‘electro-fiction.’ ”114

In their totality, the economic measures introduced after March 1921 marked a severe setback for the hopes once entertained of introducing Communism into Russia. Triumphant wherever sheer force decided the issue, the Bolsheviks were defeated by the inexorable laws of economic reality. In October 1921 Lenin admitted as much:

We had counted—or, perhaps it will be more correct to say, we had assumed without adequate calculation—on the [ability] of the proletarian state to organize by direct command state production and state distribution of goods in a Communist manner in a country of small peasants. Life has demonstrated our mistake.115

To the Bolsheviks, the loosening of economic controls, which allowed, however conditionally, the reemergence of private enterprise, spelled political danger. They made certain, therefore, to accompany liberalization of the economy with a further tightening of political controls. At the Eleventh Party Congress Lenin explained the reasoning behind these seemingly contradictory policies as follows:

It is very difficult to retreat after a victorious grand advance. Now the conditions are entirely different. Before, even if you did not enforce discipline, all pushed and rushed forward on their own. Now, discipline has to be more deliberate. It is also a hundred times more necessary, because when the entire army is in retreat, it does not know, it does not see where to stop: all it sees is the retreat. Here a few panicky voices are enough to produce general flight. Now the danger is immense. When such a retreat occurs in a real army, they deploy machine-guns, and when an orderly retreat turns into rout, they order: “Tire.” And rightly so.*

The period 1921–28 thus combined economic liberalization with intensified political repression. The latter took the form of persecution of such independent institutions as still survived in Soviet Russia, namely the Orthodox Church and the rival socialist parties; increased repression of the intelligentsia and the universities, accompanied by mass expulsions from the country of intellectuals considered especially dangerous; intensified censorship; and harsher criminal laws. To those who objected that these measures would create a bad impression abroad at the very time when the Soviet state was gaining favor for its economic liberalization, Lenin responded that there was no need to please Europe: Soviet Russia should “move further in strengthening the interference of the state in ‘private relations’ and civil affairs.”116

The main instrument of such interference was the political police, which under NEP was transformed from an agency of blind terror into an all-pervasive branch of the bureaucracy. According to an internal instruction, its new tasks were to keep close watch on economic conditions, prevent “sabotage” by anti-Soviet parties and foreign capital, and ensure that goods destined for the state were of good quality and delivered on time.117 The extent to which the security police penetrated every facet of Soviet life is indicated by the positions held by its head, Felix Dzerzhinskii, who served, at one time or another, as Commissar of the Interior, Commissar of Transport, and Chairman of the Supreme Council of the National Economy.

The Cheka was thoroughly hated, and the disrepute it was held in for shedding innocent blood was brought still lower by its venality. In late 1921, Lenin decided to reform it along the lines of the tsarist secret police. The Cheka was now divested of authority over ordinary (other than state) crimes, which were henceforth to be dealt with by the Commissariat of Justice. In December 1921, while acclaiming the Cheka for its accomplishments, Lenin explained that under NEP new security methods were required and that “revolutionary legality” was the order of the day: the stabilization of the country made it possible to “narrow” the functions of the political police.118

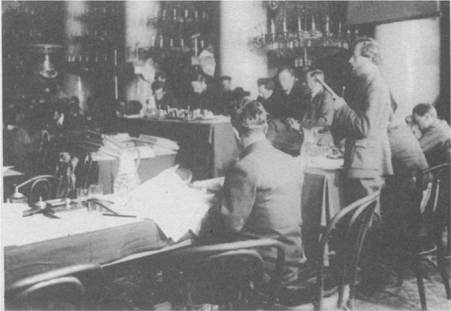

61. In the middle, Dzerzhinskii; on his right, Demian Bednyi, 1920.

The Cheka was abolished on February 6, 1922, and immediately replaced by an organization innocuously named State Political Administration, or GPU (Gosudarstvennoe politicheskoe upravlenie). (In 1924, following the creation of the Soviet Union, it was renamed OGPU or “United State Political Administration.”) The management remained unchanged, with Dzerzhinskii as head, Ia. Kh. Peters as Deputy, and everyone else in place so that “hardly a Chekist stirred from the Lubianka.”119 Like the tsarist Department of Police, the GPU was made part of the Ministry (Commissariat) of the Interior. It was to suppress “open counterrevolutionary actions, including banditry,” combat espionage, protect railroads and waterways, guard Soviet borders, and “carry out special assignments … for the defense of the revolutionary order.”120 Other crimes fell within the purview of the courts and Revolutionary Tribunals.

On the face of it, the GPU enjoyed fewer arbitrary powers than the Cheka. But the reality was different. Lenin and his associates believed that problems were caused by people, and that one solved them by getting rid of troublemakers. In March 1922, barely one month after he had brought it into existence, Lenin advised Peters that the GPU “can and must fight bribery” and other economic crimes by shooting the offenders: a directive to this effect was to be sent to the Commissariat of Justice through the Politburo.121 A decree of August 10 authorized the Commissariat of the Interior by the device of administrative procedure to exile citizens accused of “counterrevolutionary activity” either abroad or to designated localities in Russia for up to three years.122 An appendix to this decree, issued in November, licensed the GPU to deal with “banditry” as it saw fit, without resort to legal procedures, “up to execution by shooting”; it was further empowered to combine exile with forced labor.123 In January 1923, the judiciary prerogatives of the GPU were expanded still further, with the authority to exile “persons whose presence in a given locality (and within the borders of the [Russian Republic]) appears, from their activity, their past, [or] their connection with criminal circles, dangerous from the point of view of safeguarding the revolutionary order.”124 As under tsarism, exiles reached their destination guarded by an armed convoy, partly on foot, under harsh conditions. In theory, exile was imposed by the Commissariat of the Interior on the GPU’s recommendation, but in practice, a recommendation from the GPU was tantamount to a sentence. On October 16, 1922, the GPU received the power to punish without trial, and even to execute, persons guilty of armed robbery or banditry and caught in the act.125 Thus, within less than a year of its creation as an organ of “revolutionary legality,” the GPU reacquired the arbitrary powers of the Cheka over the lives of Soviet citizens.

The GPU/OGPU evolved a complex structure, with specialized departments responsible for matters not strictly within the purview of the political police, such as economic crimes and sedition in the armed forces. It was compelled to reduce its staff—from 143,000 in December 1921 to 105,000 in May 1922126—but even so, it remained a formidable organization. For in addition to its civilian personnel, it disposed of a sizeable military force in the form of an army that in late 1921 numbered in the hundreds of thousands, as well as a separate corps of border guards of 50,000 men.127 Deployed across the country, these troops performed functions analogous to those of the tsarist Corps of Gendarmes. The GPU established “agencies” (agentury) abroad with the twin mission of surveillance and disruption of Russian emigration, and supervision of Comintern personnel. GPU also helped Glavlit implement censorship laws and administered most prisons. There was hardly a sphere of public activity in which it was not involved.

Under the NEP, the network of concentration camps expanded: from 84 in late 1920 to 315 in October 1923.128 Some were run by the Commissariat of the Interior, others by the GPU. The most notorious of these camps were located in the far north (the “Northern Camps of Special Designation,” or SLON), where escape was virtually impossible. Here, along with ordinary criminals, were confined captured officers of the White armies, rebellious peasants from Tambov and other provinces, and Kronshtadt sailors. The death toll among the inmates was high: in one year (1925) SLON recorded 18,350 deaths.129 When, in the summer of 1923, these camps became overcrowded, the authorities converted into a concentration camp the ancient monastery on Solovetsk Island, which had been used to confine persons accused of antistate or antichurch crimes since the reign of Ivan the Terrible. In 1923, the Solovetskii Monastery camp, the largest operated by the GPU, held 4,000 inmates, including 252 socialists.130

The principle of “revolutionary legality” was routinely violated under the NEP, as before, not only because of the extensive extra-judiciary powers given the GPU but also because Lenin regarded law as an arm of politics and courts as agencies of the government. His conception of law became clear in 1922 during the drafting of Soviet Russia’s first criminal code. Dissatisfied with the draft submitted by the Commissar of Justice, D. I. Kurskii, Lenin gave precise instructions on how to deal with political crimes. These he defined as “the propaganda and agitation or participation in organizations or assistance to organizations that help (by means of propaganda and agitation)” the international bourgeoisie. Such “crimes” were to be punished by death, or, in the event of extenuating circumstances, by imprisonment or expulsion abroad.131 Lenin’s formulation resembled the equally vague criteria of political crimes given in 1845 in the criminal code of Nicholas I, which mandated severe punishment for persons “guilty of writing or spreading written or printed works or representations intended to arouse disrespect for Sovereign Authority, or for the personal qualities of the Sovereign, or for his government.” Under tsarism, however, such actions were not punishable by death.132 Implementing Lenin’s instructions, jurists drew up Articles 57 and 58, omnibus clauses that gave courts arbitrary powers to sentence undesirables for alleged counterrevolutionary activity, which Stalin would later use to give the appearance of legality to his terror. That Lenin realized the implications of his instructions is evident from the guidance he gave Kurskii: the task of the judiciary, he wrote, was to provide “a principled and politically correct (and not merely narrowly juridical) … essence and justification of terror.… The court is not to eliminate terror … but to substantiate it and legitimize it in principle.”133 For the first time in legal history, the function of legal proceedings was defined to be not dispensing justice but terrorizing the population.

Communist legal historians, discussing the legal practices of the 1920s, defined law as “a disciplining principle that helps strengthen the Soviet state and develop the socialist economy.”* This definition justified the repression of any individual or group that, in the judgment of the authorities, harmed the interests of the state or inhibited the development of a new economic order. Thus the “liquidation” of “kulaks,” carried out by Stalin in 1928–31, in which millions of peasants were dispossessed and deported, mostly to death camps, was carried out strictly within the terms of Leninist jurisprudence.134 According to Article No. 1 of the first Soviet Civil Code (1923), the civil rights of citizens were protected by law only to the extent that these rights did not “contradict their socioeconomic purpose (naznachenie).”135

To make it easier forjudges to carry out their new responsibilities, Lenin freed them from customary courtroom procedures. Several innovations were introduced. Crime was determined not by formal criteria—the infraction of a law—but by its perceived potential consequences, that is, by a “material” or “sociological” standard, which defined it as “any action or inaction dangerous to society, which threatens the foundations of the Soviet regime.”136 Guilt could also be established by proving “intent,” the object of punishment being “subjective criminal intention.”* In 1923, in an appendix to Article 57 of the Criminal Code, “counterrevolutionary” activity was defined in so broad a fashion as to cover any deed of which the authorities disapproved. It stated that in addition to actions committed for the express purpose of overthrowing or weakening the government or rendering assistance to “the international bourgeoisie,” “counterrevolutionary” qualified also actions that

without being directly intended to attain [these] objectives, nevertheless, as far as the person committing the act was concerned, represented a deliberate assault (pokushenie) on the fundamental political and economic conquests of the proletarian revolution.137