THE THERAPEUTIC UTILITY OF SHOPPING: RETAIL THERAPY, EMOTION REGULATION, AND WELL-BEING

1NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE (NUS) BUSINESS SCHOOL, NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE, SINGAPORE

2UNIVERSITY OF ST. GALLEN, ST. GALLEN, SWITZERLAND

Introduction

Driven by the goal of promoting individual well-being in the country, the Ministry of Health and Welfare of the Taiwanese government has been administering an annual Nutrition and Health Survey in Taiwan (NAHSIT) since 1993 to understand the contemporaneous state of health and nutrition of its people. A few years ago, a team of researchers decided to put the survey to novel use (Chang, Chen, Wahlqvist, & Lee, 2011). Creatively, they took the answers of the representative 1,841 elderly respondents (aged 65 and above) from the 1999–2000 surveys and linked them to the country’s National Death Registration records from the following decade (1999–2008). The results were astounding. The researchers found that elderly respondents who shopped daily had a 27% lower risk of death than the least frequent shoppers, with the effect being stronger for males (28%) than for females (23%).

The publication of these surprising findings created a small stir as it quickly led to a flurry of follow-up coverage and commentaries in the popular media (Adams, 2011; Gregory, 2011; NBCNews, 2011), with academics and non-academics alike placing the findings under their microscope of suspicion and scrutiny. Could the results be in fact a case of reverse causality, such that healthier and physically more able senior citizens are also more likely to shop regularly? Or might the results be explained by the presence of a third factor such as financial status or cognitive ability that accounts for both regular shopping and longevity simultaneously? To the authors’ credit, they had meticulously controlled for a plethora of individual differences (including demographics, socioeconomic status, physical functioning, physical mobility, and health conditions) in their data analysis, while fitting a variety of models to their data to validate the robustness of their empirical findings.

Regardless of the veracity of the causal relationship, one could reasonably make two general observations about this research. First, there appears to be a positive correspondence between shopping and well-being, irrespective of the reason(s) for this positive relationship. Second, a closer examination of the published results suggests that, for the elderly, buying may not be the sole or primary purpose of shopping. In other words, if shopping indeed affords consumers positive therapeutic utility, this utility may be derived from other aspects of shopping beyond buying.

The Therapeutic Powers of Shopping

The fact that people shop for myriad reasons has been well documented in the marketing and consumer psychology literature. In his seminal work, Tauber (1972) describes a variety of shopping motivations, classifying each motivation as either a personal shopping goal (e.g., diversion, self-gratification, and learning about new trends) or a social shopping goal (e.g., communication with others having a similar interest, pleasure of bargaining, and status and authority). Recognizing that consumers do not only shop when they have something specific they want to purchase, Arnold and Reynolds (2003) further define a number of different hedonic motivations (e.g., adventure shopping, social shopping, and gratification shopping) that draw people to retail stores, based on the results of a series of in-depth interviews they conducted. Although these are not the only classifications of shopping motivations in the extant literature (Babin, Darden, & Griffin, 1994; Ganesh, Reynolds, Luckett, & Pomirleanu, 2010; Stone, 1954; Westbrook & Black, 1985; see Lee, 2015 for a recent review), the various taxonomies share a common thread: shopping is driven not only by utilitarian goals but also by hedonic goals, and that shopping could serve important therapeutic functions.

Consumers seem well aware of the hedonic and potentially therapeutic effects of shopping. In a recent study conducted by Ebates.com (Cooper, 2013), 51.8% of the 1,000 American adults surveyed reported to have engaged in retail therapy to improve their mood, be it after experiencing an unpleasant day at work, receiving some bad news, or engaging in an altercation with a significant other. (Interestingly, more than 500 people every month apparently tweeted wishing that retail therapy were covered by their health insurance! [eHealth, 2015]) In another survey commissioned by the Huffington Post (Gregoire, 2013), nearly one in three Americans shops to alleviate stress. Similar figures have also been reported in academic investigations (Atalay & Meloy, 2011). On the other hand, it has been found that, besides work and sleep, shopping is a daily activity on which people around the world spend the most amount of their time (Hutton, 2002). If shopping indeed brings about mood repair and other therapeutic benefits (Isen, 1984), what exactly about shopping contributes toward retail therapy? In other words, what are the potential mechanisms by which shopping brings about therapeutic benefits?

In this research, we attempt to address this question by adopting a needs perspective. Specifically, we draw upon a breadth of prior work in shopping and retailing, needs and motivation, the role of emotions in judgments and decisions, and more recently, compensatory consumption to propose an integrative conceptual framework that could guide the systematic study of retail therapy. We discuss how this framework serves to capture the varied positive therapeutic effects that shopping may provide. In addition, based on the framework, we also derive and discuss a number of potential questions and directions for future research. We hope that our humble efforts at integrating work from several separate streams of research that are relevant to retail therapy would spur more future work in this important but hitherto understudied domain.

Defining Retail Therapy and Therapeutic Utility

Before introducing and elaborating on our proposed conceptual framework, it is essential to first clarify our definition of retail therapy. Put simply, retail therapy refers to the use of shopping and buying as a means to repair or alleviate negative feelings (Atalay & Meloy, 2011; Babin, Darden, & Griffin, 1994; Faber & Christenson, 1996; Isen, 1984; Lee, 2015; Rick, Pereira, & Burson, 2014). Hence, in order to distinguish retail therapy from shopping in general, we shall limit our discussion to shopping with the goal of repairing one’s negative feelings as opposed to amplifying one’s already positive feelings or purely utilitarian shopping. For example, neither a celebratory trip to the shopping mall after a positive life event nor a routine trip to the neighborhood supermarket would fall under our consideration, except when the latter was motivated by a need to feel better.

Importantly, consumers can engage in retail therapy without pursuing any concrete purchase goals or making any actual purchases. Whether it is the ability to distance oneself from one’s negative feelings and worldly concerns, or the experience of immersing oneself within the sights, sounds, and scents in the scintillating retail environment, window-shopping or browsing without buying (Bloch & Richins, 1983; Moe, 2003) may be just as effective as purchasing in “mending the broken soul” and helping consumers achieve retail therapy.

Furthermore, rather than being part of a general negative mood state, the negative feelings that motivate the quest for retail therapy may be symptoms of a perceived psychosocial deficiency. In this vein, some research has defined retail therapy, perhaps more specifically, as the consumption of goods to compensate for perceived psychosocial deficiencies such as low self-esteem and the loss of control (Gronmo, 1988; Kang & Johnson, 2011; Sivanathan & Pettit, 2010; Woodruffe-Burton, Eccles, & Elliott, 2002; Woodruffe-Burton & Elliott, 2005). Notably, the two flavors of retail therapy are not mutually exclusive, since perceived psychosocial deficiencies often engender negative feelings and trigger the desire to consume (Mandel, Rucker, Levav, & Galinsky, 2016). Moreover, consumers who shop with a retail-therapy goal may not always be consciously aware of the source of their negative feelings (Cohen, Pham, & Andrade, 2008); for example, while people may be feeling down due to a perceived loss of control, they may not always be thinking specifically about this loss, let alone their (latent) desire to restore their sense of psychological control.

To represent the multi-faceted therapeutic benefits of shopping, for brevity, we shall use the term therapeutic utility in the rest of our discussion. We build upon prior work (Arnold & Reynolds, 2003; Babin, Darden, & Griffin, 1994; Tauber, 1972) that has shown that shopping serves myriad functions, and more importantly, that shopping affords both hedonic and utilitarian value. We argue that despite negative feelings being the dominant driver for consumers to seek retail therapy, both hedonic and utilitarian benefits of shopping potentially contribute toward the therapeutic utility of shopping.

An Integrative Framework for Retail Therapy

Overview of Proposed Framework

While considerable research has discussed the subject of retail therapy in general and the compensatory benefits of product purchases specifically (e.g., Mandel et al., 2016), there has been little work that examines the sources of therapeutic utility in the shopping process itself. Other research (e.g., Tauber, 1972; Arnold & Reynolds, 2003) describes various shopping motivations without linking them directly to retail therapy. Therefore, we aim to provide an integrated framework that assembles the various drivers of therapeutic utility in shopping.

Our proposed framework is based on a model of human motivation proposed by William J. McGuire (1974), considered by many to be the “father of social cognition” (Jost & Banaji, 2008). McGuire first proposed the model to delineate the different general paradigms of human motivation, and how the different specific needs and motives that people have could help explain the possible gratifications that people may obtain from mass communication. Subsequently, he used the framework to propose that various internal psychological factors could influence consumer choice more broadly, although how each motive in his model affects consumer choice specifically received limited discussion (McGuire, 1976). Nonetheless, compared to other models of human motivation (e.g., Maslow, 1943, Murray, 1938), McGuire’s model seems particularly apt for our purpose of examining retail therapy and the sources of therapeutic utility, given the model’s focus on illuminating the types of gratification that people derive from mass communication. In the same vein, we believe that an adapted framework based on this model could systematically direct our thinking to the different ways in which consumers could derive therapeutic utility from shopping.

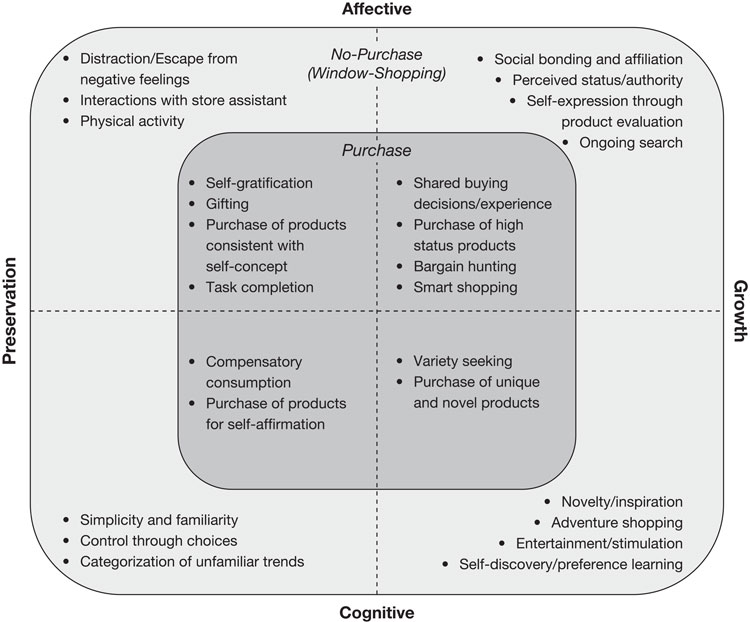

Figure 4.1 A conceptual framework for retail therapy – shopper motives and sources of therapeutic utility in shopping

For our proposed framework, we adopt the two main dichotomies in McGuire’s model (affective vs. cognitive, and preservation vs. growth)1 while adding a third (purchase vs. no-purchase) to customize it for our specific examination of retail therapy (see Figure 4.1). These three dichotomies are briefly described as follows:

1 Affective versus cognitive – Affective motives are those that stress a consumer’s need to attain satisfying emotional states or achieve certain emotional goals, while cognitive motives focus on the consumer’s need to be “adaptively oriented toward the environment” or achieve “a sense of meaning” (McGuire, 1976, p. 315). In short, affective motives pertain to consumers’ feelings whereas cognitive motives pertain to consumers’ information processing and internal belief systems. Although this affective-cognitive distinction may seem at first glance to map conceptually to mood repair and compensatory consumption, respectively, compensatory consumption could in fact be driven by both affective and cognitive responses (Mandel et al., 2016).

2 Preservation versus growth – As the names imply, preservation and growth relate to the object of human endeavor. Whereas preservation focuses on the consumer’s goal to “maintain equilibrium,” growth centers on the consumer’s “need for further growth” (McGuire, 1976, p. 315) and self-enhancement. In the shopping context, an example of a preservation motive is to buy a particular brand or product that is consistent with the consumer’s image of himself or herself. In contrast, a growth motive would involve actively seeking variety in one’s purchase in order to explore new consumption experiences and possibilities.

3 Purchase versus no-purchase – From browsing and deciding, to paying and acquiring, shopping may involve a gamut of activities that may not always follow one another sequentially (Lee, 2015). While retail therapy has traditionally been associated with product purchase, theoretical work on shopping motivations (Arnold & Reynolds, 2003; Tauber, 1972) as well as accumulating empirical evidence (Rick et al., 2014) has shown that consumers do not have to buy in order to reap the benefits of shopping. Indeed, mere window-shopping or browsing without any purchase (Bloch & Richins, 1983; Bloch, Ridgway, & Sherrell, 1989) could bring about therapeutic utility as well.

Together, these three dimensions in our framework produce four main types of shopper motives and eight different categorical sources of therapeutic utility. We shall next elaborate each of the four types of motives in this framework, discussing in detail how considering each type of motive in the context of both window-shopping and purchasing illuminates the therapeutic utility of shopping.

Achieving Affective-Preservation Motives…

Shopping may help consumers to alleviate their negative moods by satisfying their need to restore their feelings back to an equilibrium state. This mood-repair goal is akin to McGuire’s (1974; 1976) notion of the “need for tension reduction,” particularly when retail therapy is motivated by high-arousal negative feelings such as anger and stress. Broadly, this goal relates to emotion regulation, or the motivation to shape “which emotions one has, when one has them, and how one experiences or expresses these emotions” (Gross, 2014, p. 6; see also Gross 1998). In the context of retail therapy, shopping is often regarded as a means to alleviate negative feelings, and sometimes, to increase arousal so as to counter the negative and depressive state of sadness.

The role of shopping as a hedonic activity that generates positive feelings and elevates one’s mood (thus helping one to regulate one’s affective state and maintain emotional equilibrium) is well documented in most of the existing taxonomies of shopper types and motivations (Lee, 2015). Labels such as gratification shopping (Arnold & Reynolds, 2003; Tauber, 1972; Wagner & Rudolph, 2010), hedonic shopping (Babin, Darden, & Griffin, 1994; Babin & Darden, 1995; Childers, Carr, Peck, & Carson, 2001), recreational shopping (Bellenger, Robertson, & Greenberg, 1977; Brown, Pope, & Voges, 2003; Rintamäki et al., 2006; Williams, Slama, & Rogers, 1985), leisurely-motivated shopping (Jin & Kim, 2003), experience-oriented shopping (Wolfinbarger & Gilly, 2001) and mood shopping (Geuens, Vantomme, & Brengman, 2004) are just a few of the terms that have been used to describe this role of shopping. However, as we shall discuss next, several seemingly pure utilitarian aspects of shopping, such as task completion and shopping as a mere physical activity could also carry invaluable affective-preservation benefits and therapeutic utility.

…Through Window-Shopping

The hedonic value in shopping may be derived from several aspects of the activity. First, shopping can be a source of positive distraction, allowing one to escape from and, albeit momentarily, forget about one’s negative feelings (Luomala, 2002; Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1993). This attentional diversion is bolstered by the fact that shopping environments tend to be intensely arousing and stimulating to the five senses, as one is exposed to an avalanche of brands and often-massive assortment of products on display in stores, blindingly colorful billboards, window displays, and sale signs, and throngs of spirited shoppers, many of whom may also be seeking a boost of retail therapy. Marketers and retailers seem to be well aware of the influence of atmospherics and environmental factors on consumer behavior as they continue to seek a firmer understanding of sensory marketing in order to strategically influence how consumers think, feel, and behave (Arnold & Reynolds, 2003; De Nisco & Warnaby, 2014; Kotler, 1973; Krishna, 2009; 2012; Tauber, 1972; Turley & Milliman, 2000; Underhill, 2000; Zhao, Lee, & Soman, 2012; Zwebner, Lee, & Goldenberg, 2014).2

Second, perhaps a more active approach to releasing tensions involves expressing or discharging one’s negative feelings (Luomala, 2002; McGuire 1974). Some consumers may alleviate their negative feelings by venting their anger or frustration onto sales associates or other service agents. Due to the implicit power hierarchy between customers and sales associates, the latter may have no choice but to tolerate the “difficult” customer and employ coping strategies such as emotion management to deal with this situation (Grandey, 2003). These coping strategies that service agents adopt may in turn influence the customer’s satisfaction with the interaction (Groth, Hennig-Thurau, & Walsh, 2009). Shoppers may also express their negative feelings in less aggressive ways by confiding in service agents while interacting with them. For example, it is conceivable that consumers may talk with store clerks or their personal shoppers about their feelings, thus assigning the latter the role of ad-hoc therapists.

Furthermore, even the mere physical activity of shopping might foster tension reduction and help return consumers to their equilibrium emotional state. Tauber (1972) points out that shopping may provide consumers an opportunity to exercise at a leisurely pace in the urban environment. The link between physical exercise and anxiety reduction is well established in the literature (e.g., Petruzzello, Landers, Hatfield, Kubitz, & Salazar, 2012). The effort of walking from one shop to the next or wandering within a store or a mall might release mood-lifting endorphins and reduce negative feelings similar to more traditional ways of physical exercise.

…Through Purchasing

Beyond mere window-shopping, shopping that involves actual purchases may afford consumers other sources of hedonic value and therapeutic utility. Perhaps the most obvious and direct source of hedonic value is the purchase of specific products that shoppers actually enjoy consuming. Although these products clearly vary from consumer to consumer depending on their idiosyncratic preferences, a common characteristic of these products is that they provide immediate reward or instant gratification (Arnold & Reynolds, 2003; Tauber, 1972). Indeed, consumers seem to prefer immediate rewards over delayed rewards especially when experiencing negative affect (Seeman & Schwarz, 1974), and thus may choose to indulge in temporarily gratifying consumption to improve their mood. Similarly, consumers may practice self-gifting and reward themselves with self-treats when experiencing negative moods; these self-treats are typically not accompanied by feelings of guilt or regret, and could have sustained reparative benefits even if the purchases were unplanned (Atalay & Meloy, 2011). Furthermore, particularly when the purchases are unplanned, feelings of “consummatory indulgence” or the perceived freedom to buy as the heart pleases could release retail-therapy seekers from the psychological encumbrance of their negative emotions (Falk & Campbell, 1993; Wolfinbarger & Gilly, 2001).3

Rather than buying hedonic products that carry immediate rewards, consumers may also purchase products that allow them to express their negative feelings, thus allowing these feelings an outlet for psychological release. For example, some fashion brands seem to embrace negative feelings by displaying deliberately provocative or aggressive slogans and messages. By purchasing these brands, consumers might signal or express their sadness or anger at the world and, thus, alleviate their tension rather than turning it against themselves.

Besides buying products for themselves, consumers may also improve their mood by buying products for others. For example, consumers may purchase products as gifts or for shared consumption within a household. Despite providing less immediate gratification for themselves, consumers can still derive intrinsic pleasure from finding the perfect gift for a friend or a relative (Arnold & Reynolds, 2003). Furthermore, shopping for others may be part of a social role that gives consumers a sense of purpose and identity (Tauber, 1972). Due to their more altruistic nature, these types of purchases may induce less guilt than self-serving purchases. Accordingly, some research has suggested that spending money on others could generate greater happiness than spending money on oneself (Dunn, Aknin, & Norton, 2008).

At a more metacognitive level, purchasing also affords consumers positive therapeutic utility through task completion. For example, related to the aforementioned discussion on role shopping, the comfort in completing a routine grocery-shopping chore, successfully accomplishing a planned shopping task, or simply checking things off one’s shopping list could give rise to a sense of relief or even a feeling of accomplishment, generating positive feelings of competency and self-efficacy (Carver & Scheier, 1990; Falk & Campbell, 1993).

Achieving Affective-Growth Motives…

While shopping may help repair consumers’ negative feelings by restoring their emotions to an equilibrium state, it also allows consumers to achieve retail therapy by satisfying needs that are associated with the motivation to achieve elevated affective states. Whereas affective-preservation motives are more conservative in essence, affective-growth motives are associated with self-improvement and greater promotion orientation (Higgins, 1997).

Two specific needs in line with affective-growth motives are of particular relevance to retail therapy. First, people generally have a need for social affiliation and to develop camaraderie and mutually satisfying relationships with others. This need, for instance, is arguably a key driver of many altruistic acts and pro-social behaviors. Conversely, loneliness and social exclusion have been linked to numerous adverse effects (Cacioppo & Patrick, 2008; Pieters, 2013). In the retail therapy context, shopping, being a highly social activity by nature, can provide ample opportunities for consumers to bond and affiliate with other consumers.

Second, people may also have an intrinsic need to boost their self-esteem, a need for achievement, success, and power, and the need to be admired and respected by others. Such needs relate closely with Maslow’s (1943) “need for esteem,” and to some extent, also with his “need for self-actualization.” Be it directly or indirectly, shopping can also serve as an important conduit for consumers to attain these affective-growth needs in their daily lives.

Interestingly, recent research suggests that these two seemingly disparate needs may be related to each other. In particular, Lee and Shrum (2012) examine the impact of two distinct antecedents of perceived social exclusion and their differing consequences. On the one hand, perceived social exclusion arising from the feeling of being rejected by others enhances relational needs and the need to enhance one’s self-esteem, which could in turn lead to greater pro-social behavior. On the other hand, perceived social exclusion arising from the feeling of being ignored leads to greater efficacy needs, as well as the need for power and the perception of a meaningful existence; such needs could in turn increase conspicuous consumption instead.

To the extent that the various aspects of window-shopping and purchasing that we discussed in the preceding section on affective-preservation motives contribute to producing an elevated affective state, they could arguably also satisfy consumers’ affective-growth motives. Conversely, the additional aspects of window-shopping and purchasing that we shall discuss next are potentially mood-lifting and would certainly help to restore one’s emotional equilibrium state. However, we discuss these additional aspects in the present section because they pertain specifically to people’s affective-growth motives: the need for social affiliation and the need for esteem and achievement.

… Through Window-Shopping

To many consumers, shopping is essentially a social activity. Shopping is often viewed as a convenient yet valuable opportunity for people to bond and to spend quality time with their friends and family, regardless of whether the shopping trip arises from any concrete spending goals (Bellenger, Robertson, & Hirschman, 1978). Shopping is also a shared experience that provides people with a common ground to communicate and exchange information and opinions about products, brands, and retail experiences with their shopping companions. These people-oriented goals for shopping are underscored in Tauber’s (1972) seminal work on shopping in which he emphasizes two main types of shopping motives – personal and social. Importantly, pertinent to our present study of retail therapy, people’s desire for social connectedness is especially amplified when they experience sadness, evident in their greater attention toward non-verbal information (e.g., others’ vocal tone) and their greater propensity to engage in social activities (Gray, Ishii, & Ambady, 2011). These results implicate the social elements of shopping as a principal factor that generates positive feelings and therapeutic utility.

The social benefits of shopping may not only stem from shopping with familiar others. Even when shopping alone, being with like-minded consumers with similar interests in the same retail environment can enhance one’s shopping experience by bolstering the perception that one is surrounded by empathetic others, and allowing one to interact and build social connections with similar others (Borges, Chebat & Babin, 2010). Moreover, some shoppers may enjoy the attention that they receive from members of the sales staff, perceiving a sense of psychological power from being served and waited on by others (Tauber, 1972). Some research even suggests that the mere presence of crowds in a store can increase shopping satisfaction (Eroglu, Machleit, & Barr, 2005).

Apart from the potential social benefits of window-shopping, browsing without buying can elevate one’s positive feelings through satisfying one’s need for achievement and self-improvement. For example, consumers often derive pleasure simply from evaluating whether they like or dislike target objects (He, Melumad, & Pham, 2013). Such evaluation-derived pleasure (without buying) is perhaps exemplified in people’s willingness to express their liking or disliking for particular media content on YouTube, Facebook, and other social media platforms. Empirical findings suggest that people may derive joy from the ability to express themselves through assessing and externalizing their personal preferences.

Another source of self-improvement pleasure that consumers often derive from window-shopping is their actual (or perceived) gain in knowledge about products, brands, and trends about the retail landscape. Bloch and his collaborators (Bloch, Ridgway, & Sherrell, 1989; Bloch, Sherrell, & Ridgway, 1986) describe such pleasure as the pleasure from information seeking or ongoing search. Given that ongoing search satisfies both affective-growth and cognitive-growth motives, we shall defer our discussion of this important source of therapeutic utility to a later section when we examine how shopping may satisfy consumers’ cognitive-growth motives.

…Through Purchasing

Some social aspects of shopping may also generate positive affect and therapeutic utility through actual purchases. For example, making joint buying decisions or having a shared buying experience with familiar others can foster closer interpersonal ties and enhance overall buying satisfaction (Corfman & Lehmann, 1987; Filiatrault & Ritchie, 1980; Van Raaij & Francken, 1984).4

Moreover, some shoppers derive considerable hedonic pleasure through taking advantage of price discounts and other forms of sales promotions (Blattberg & Neslin, 1990; Chandon, Wansink, & Laurent, 2000; Lee & Tsai, 2014; Lichtenstein, Netemeyer, & Burton, 1990). Besides economic savings (whether real or perceived), discounts and promotions satisfy many shoppers’ hunter-gatherer motive in shopping (Arnold & Reynolds, 2003) such that shoppers derive deep satisfaction from being able to discover hard-to-find deals or having invested effort in locating or qualifying oneself for these deals. The perception that one has got a good deal also feeds consumers’ smart-shopper mindset, especially among deal-prone consumers (Lichtenstein, Burton, & Netemeyer, 1997); such a mindset boost is not only mood-elevating for the shopper but may also lead to positive downstream consequences for the retailer, such as increased brand loyalty and positive word-of-mouth (Schindler, 1989; 1998). Furthermore, certain types of promotions (e.g., conditional promotions such as “Buy $10 and get $1 off”) may also serve as external cues to guide shoppers in deciding how much to spend and what to buy in a store (Lee & Ariely, 2006). In summary, the explicit transaction utility (or the perception of having received a good deal; Thaler, 1985) that consumers derive from discounts and promotions, as well as the more implicit decision assistance that shoppers may receive from promotions in setting concrete spending goals, could promote a sense of achievement in many respects and, in turn, contribute substantially to the therapeutic utility in shopping.

While bargain hunting can be regarded as a form of competition that shoppers engage in with their fellow shoppers, particularly when the number of units under promotion is limited, some shoppers also derive satisfaction and a sense of achievement through negotiating and bargaining with sellers, particularly in retail environments where price haggling is a norm (Ganesh et al., 2010; Tauber, 1972). Likewise, Arnold and Reynolds (2003) report that consumers feel like “winning a game” when they obtain the best value for their money. Through expending effort in price negotiations, shoppers may perceive the prices they have paid to be lower than the average selling price, thus fueling the smart-shopper mindset. Furthermore, this phenomenon may not be limited to finding the lowest prices, but can also relate to minimizing the amount of time and energy that one expends for a shopping trip (Atkins & Kim, 2012). The advent of omni-channel retailing and new shopper-marketing technologies may afford consumers increasing convenience and flexibility in bolstering such a mindset (Neslin et al., 2014; Shankar et al., 2011). More recently, some retailers have also started using gamification to appeal to this desire for competition and need for achievement (Insley & Nunan, 2014). Finally, the success of having shaved off some proportion of the original selling price may also engender a sense of power in shoppers over the seller or the retailer.

Further, beyond receiving ego-boosting customer service from sales associates, taking advantage of scarce deals, and successfully bargaining for a lower price, consumers’ psychological sense of power in the retailing environment can also be derived from buying specific types of products in a store. The symbolic association with social power that these products possess could generate positive feelings and contribute to a sense of personal achievement. Such products include high-status brands, exclusive or limited-edition items, and highly innovative products (Rucker & Galinsky, 2008; Vandecasteele & Geuens, 2010).

Achieving Cognitive-Preservation Motives…

Besides affective motives, consumers may also be driven by cognitive motives in their behavior. By cognitive motives, we refer to people’s information processing proclivities, in particular, their desire to adapt to their extant environments and seek meaning in these environments (McGuire, 1974). These motives are anchored in the view that humans are implicit theorists that maintain an inner model to make sense of the world around them and their role(s) in it. The understanding of the rules and actors in the world is complemented by a system of values and goals that guide human behavior (Kruglanski et al., 2002).

One set of cognitive motives, which we examine in the present section, is essentially conservative and directed toward maintaining achieved orientations (McGuire, 1974). This set of motives comprises several conceptually distinct yet highly correlated needs. First, humans have a need for consistency between their internal belief systems and influences from external sources as well as their own behavior (Festinger, 1957). In its most basic form, consumers might therefore strive for reassurance that their world-view is accurate and their actions make sense. Second, when faced with new information, humans have a need to integrate the information into their existing cognitive systems (Anderson, 1995). That is, a cognitive-preservation motive would drive consumers to make sense of new trends and phenomena in accordance with their existing mental categories. Third, humans also need to maintain a consistent view about themselves, their identity, and their role(s) in this world (Cialdini, Trost, & Newsom, 1995). Therefore, consumers are also looking for external cues that confirm their self-concept, including the level of their perceived status and their own preferences. Finally, humans have a need to know the extent to which their actions can actively shape the environment. Hence, consumers have a need for control and a need to understand other forces that shape their environment (Averill, 1973; Kay et al., 2009; Landau, Kay, & Whitson, 2015).

As we shall discuss next, various aspects of shopping may help to preserve one’s cognitive views of the world and of oneself. By giving consumers the assurance that their views are not threatened, these aspects of shopping may carry therapeutic utility. While the focus of retail therapy has traditionally been on regulating negative emotions, these cognitive-preservation effects of shopping present a more holistic view of retail therapy by illuminating the ability of shopping to meet specific cognitive needs of consumers, which may in turn generate positive feelings. Importantly, affective and cognitive needs may be related such that a threat to one’s belief system (e.g., a perceived lack of control) may induce negative feelings (e.g., Rick et al., 2014). Hence, cognitive needs may often be seen as the underlying cause and negative feelings as the more ostensible symptoms that lead to the quest for retail therapy.

…Through Window-Shopping

When consumers’ cognitive belief systems about the world and themselves are threatened, they may go shopping to regain a sense of consistency. Compared with the complexities of the world at large, most shopping environments present relatively simple and ordered surroundings: There is a steady stream of familiar shops, clear roles, such as the customer and the seller, and well-defined rules that govern social interactions, such as the exchange of money for goods. Even the products that are displayed on the shelves and at the store windows are, in general, neatly and logically ordered by category, brand, color, and size. This simplicity and familiarity of the shopping environment can be soothing and therapeutic for consumers who may feel overwhelmed or challenged by the complexities of the world. Similar to the notion of escapism discussed earlier, shoppers may immerse themselves in the fantasy of a simpler familiar world.

The shopping environment may also address the need to categorize and make sense of new and unfamiliar trends in accordance with existing mental categories. Familiar retailers and their brands provide an easily accessible framework via which consumption-related trends can be categorized. For example, shoppers can observe which stores promote a certain new-product trend (i.e., the trendsetters) and which fellow shoppers tend to follow the trend; they can then easily infer that a particular trend pertains to a certain group of consumers based on their observations. In this way, new trends can be subsumed under the existing mental categories that consumers have acquired over time.

Finally, consumers may regain a feeling of control via shopping. Prior research suggests that a lack of control induces people to search for simple, clear, and consistent structures (Landau et al., 2015). Furthermore, almost everything is available for sale in a shopping environment and could be acquired and owned, at least theoretically, for a given price. The decision of whether to buy or not to buy lies almost exclusively with the shopper. Even if shoppers were to decide against making a purchase, they may gain a sense of psychological control from making this decision. In fact, prior research suggests that this feeling of control can alleviate feelings of sadness and is one of the main drivers of retail therapy (Rick et al., 2014).

…Through Purchasing

While the activity of shopping can help consumers achieve cognitive-preservation motives to some extent, the actual purchasing of items can carry additional therapeutic utility. From an early age, humans begin to develop a sense of the “extended self” that includes not only their physical self, but also their material possessions and even immaterial goods (Belk, 1988; 2013). Furthermore, consumers tend to ascribe the qualities of their possessions to themselves. For example, in a thought-provoking experiment conducted by Weiss and Johar (2016), consumers who owned a tall (vs. small) mug were inclined to perceive themselves as taller (see also Weiss & Johar, 2013). Thus, our possessions not only reflect who we are, but also influence our own concept of ourselves. If consumers’ views about their role in the world come under threat, they may therefore turn to their possessions to look for reassurance and self-affirmation.

Indeed, research suggests that consumers might see their material possessions as more representative of who they are when they are uncertain about their self-concept (Berger & Heath, 2007; Chatterjee, Irmak, & Rose, 2013; Morrison & Johnson, 2011; Sivanathan & Pettit, 2010). Moreover, consumers may also add new symbolically meaningful possessions to their extended selves if they perceive a discrepancy between their current selves and the ideal selves they are striving to achieve. This important aspect of consumer behavior has been termed compensatory consumption and may be responsible for a large part of retail therapy (Chen, Lee, & Yap, 2017; Mandel et al., 2016; Rucker & Galinsky, 2008; Woodruffe, 1997).

In general, the type of purchase that will yield the highest therapeutic utility depends on the specific domain of the perceived threat to one’s self-concept. In a recent review of the compensatory consumption literature, Mandel and her colleagues (2016) document a comprehensive list of self-discrepancy domains that range from academic ability and physical appearance to social factors and gender identity. For example, consumers whose self-views about their intelligence were shaken were more likely to favor products that are commonly associated with intelligence (e.g., a Rubik’s cube) over neutral products (e.g., a Magic 8 Ball) to bolster their self-views (Gao, Wheeler, & Shiv, 2009). Likewise, men whose masculine self-view was threatened by false feedback were more interested in buying a product associated with masculinity (e.g., an SUV) than a more gender-neutral product (e.g., a sedan; Willer, Rogalin, Conlon, & Wojnowicz, 2013). More recently, it has been found that consumers who experience a momentary loss of psychological control over outcomes in their environment demonstrate a stronger preference for utilitarian products (e.g., a pair of sneakers featuring its functionality) than hedonic products (e.g., a pair of sneakers featuring its style); this effect arises because of utilitarian products’ general association with problem-solving, a quality that promotes a sense of control (Chen et al., 2017).

Importantly, research suggests that such efforts to repair the shaken self through compensatory consumption might indeed be successful. For example, Rucker, Dubois, and Galinsky (2011) first induced feelings of high or low power in participants and then offered them a pen that was either associated with status or simply with quality. Their results suggest that participants in the low-power condition felt more powerful when the pen they received was associated with status than with quality. Likewise, Chen et al. (2017) find that the opportunity to choose between utilitarian products instead of hedonic products following the recall of a control-depriving episode restores one’s sense of control to baseline levels. Therefore, it appears that the purchase of particular products with symbolic significance during shopping can indeed alleviate perceived threats to one’s cognitive self-views.

Achieving Cognitive-Growth Motives…

In addition to preserving one’s existing cognitive belief system, one may also seek to develop and elevate one’s cognitive status quo (McGuire, 1974). Arguably, such cognitive-growth motives are just as important as preservation motives since they allow people to adapt to changes in their environment and bolster self-actualization, which Maslow (1943) describes as the highest form of human motivation.

One such cognitive-growth motive is the need for stimulation, novelty, and knowledge, based on the view that humans are naturally curious and therefore need a variety of stimuli for their mental well-being. On the one hand, moments of inspiration, which are characterized by the sudden realization of a new and better insight, are highly motivating and lead to positive affect (Thrash & Elliot, 2003; 2004). On the other hand, the lack of inspiration has been described as leading to depression, anxiety, alienation, and obsession (Hart, 1998).

Cognitive growth also involves a need for autonomy and a sense of freedom, independence, or self-governance (McGuire, 1974). These needs are closely related to the need for control and focus on humans’ desire to influence their own destiny. They also involve an appetite for power at least over oneself. However, the notion of growth implies that humans are in general not completely autonomous. At any moment in time, consumers are faced with multiple financial, societal, and sometimes even physical constraints that limit the actions they can take. Therefore, consumers are generally striving for higher levels of autonomy.

Finally, cognitive growth also includes the desire to achieve one’s goals and to excel. These motives are related to what McGuire (1974) describes as teleological and utilitarian theories. Accordingly, people carry within their heads patterns of end states that they strive for. In its most abstract form, these patterns may take the form of broad values with varying importance (e.g., Schwartz, 1992). At a more concrete level, the patterns can be described as a network of goals, sub-goals, and associated means to achieve these goals (Kruglanski et al., 2002). The cognitive-growth motives described here stem from the view that consumers regularly assess their current status quo and compare it to desired end states (Higgins, 1987). Consumers desire locomotion such that they approach their goals progressively over time rather than moving away from them.

Of course, life can be turbulent and often does not resemble the smooth linear progression toward one’s goals that consumers may wish for. When consumers feel trapped in their pursuit of cognitive growth, they may turn to shopping as an alternate way to regain a sense of cognitive development, autonomy, and achievement, acquiring therapeutic utility through either the shopping activity itself or the act of purchasing.

…Through Window-Shopping

Shops and shopping malls present a rich and ever-changing environment that can stimulate consumers’ minds and give consumers new ideas. Hence, there are multiple ways in which window-shopping may contribute toward therapeutic utility through promoting cognitive growth.

First, shoppers may search for pure stimulation as a cure against boredom. Tauber (1972, p. 47) points out that shopping “can provide free family entertainment without the necessity of formal dress or preplanning.” Arnold and Reynolds (2003) further describe the search for adventure, thrills, stimulation, and excitement as a prevalent hedonic shopping motive. This entertainment aspect of the shopping environment is also visible in popular media. For example, the travel website TripAdvisor ranks both New York’s most popular shopping street, Fifth Avenue, and one of London’s most well-known department stores, Harrods, within the top 100 attractions in their respective cities. Likewise, no travel guide for most other cities would be complete without an extensive section on shopping. Based on their survey of shoppers in a mall, Bloch, Ridgway, and Dawson (1994) estimate that approximately 20% of shoppers belong to a cluster labeled “Grazers” that is motivated by the desire to alleviate boredom. Thus, shopping may provide therapeutic utility through a stimulating retail environment.

In addition to providing stimulation and entertainment, shopping can also provide opportunities to learn and expand one’s mental horizon. Prior research suggests that the shopping motive to learn about new products and trends is distinct from the mere desire for stimulation (Arnold & Reynolds, 2003; Bloch et al., 1986; Tauber, 1972). This therapeutic utility is related more to consumers’ need for novelty (McGuire, 1974) and their search for inspiration (Wagner & Rudolph, 2010). Thus, consumers may go shopping to alleviate a perceived lack of inspiration in their lives. Research by Bloch and colleagues (1994) suggests that around 24% of shoppers might belong to a cluster labeled “Mall enthusiasts” and benefit from this epistemic value of shopping. The novelty provided by new products, changing assortments, and combinations of products in a shopping environment can, thus, create therapeutic utility for consumers looking for new ideas and inspiration in their lives.

Finally, consumers may also turn to shopping to learn about themselves and their own preferences. Research suggests that consumers may often have inconsistent or incomplete preferences, and tend to construct, rather than reveal, their preferences in response to judgment or decision tasks (Payne, Bettman, & Johnson, 1993). As discussed earlier, He et al. (2013) found that consumers derive pleasure from simply evaluating whether they like or dislike products. In addition to the joy consumers derive from the self-expressive aspects of “liking,” consumers may also enjoy the self-discovery aspects of evaluating their preferences. In other words, consumers may learn about their own preferences when deciding whether they like or dislike products. Window-shopping and browsing in a store can thus provide consumers many opportunities to assess the desirability of brands and items, promote self-discovery, and in turn, satisfy a latent need for novelty.

… Through Purchasing

Purchasing, besides mere browsing, can also generate therapeutic utility through promoting cognitive growth. For example, consumers often buy new or unfamiliar products to experience novelty or seek variety. Variety seeking often arises from the intrinsic motivation for stimulation and a feeling of satiation with one’s usual choice (McAlister & Pessemier, 1982). This need for exploration and novelty may lead consumers to choose variety even when it means forgoing a more desirable known alternative (Ratner, Kahn, & Kahneman, 1999). Interestingly, however, variety seeking may also benefit consumers in the long run, since it provides them with a portfolio of options to hedge against future uncertainties (Kahn, 1995). Consequently, when consumers who feel a general lack of novelty in their lives turn to variety seeking as a remedy, they may build a bank of knowledge from which they could benefit in the future.

Furthermore, existing research suggests that consumers may regain a sense of autonomy from purchasing varied and unique products. In a series of experiments (Levav & Zhu, 2009), participants who had to walk down a narrow aisle chose a greater variety of products and lesser-known, more unique brands than participants who walked down a wider aisle. This relationship between spatial confinement and variety seeking was especially strong for participants high in reactance tendency, indicating that the choice of varied products was driven by a perceived threat to participants’ personal freedom and the desire to regain autonomy. Therefore, consumers who perceive low autonomy in their lives may gain therapeutic utility in shopping for varied or unique products; they may be especially keen to purchase products that they perceive as scarce, such as limited-edition or rare products.

Finally, variety seeking may give consumers an opportunity to portray themselves as interesting, open-minded, and creative. Some research suggests that consumers may choose more variety in public than in private to signal such favorable cognitive-growth attributes to their peers (Ratner & Kahn, 2002). Furthermore, this behavior was stronger for individuals who had the desire to fit in with a social situation, alluding to a strong affective-growth motive as well. When there was a social cue of approval to stick with one’s favorite choice, the preference for variety was attenuated. These findings suggest that variety seeking can also generate therapeutic utility by addressing one’s need for affiliation.

General Discussion

When the going gets tough, the tough go shopping.

Marshall (1991)

Shopping is a common activity in our everyday lives. The present research is mooted by the goal of understanding the various ways in which shopping can contribute toward emotion regulation and engender what we call therapeutic utility. Given the dominance of shopping in our daily lives (Hutton, 2002) and the prevalence of retail therapy as a motivation for shopping (Arnold & Reynolds, 2003; Babin, Darden, & Griffin, 1994; Isen, 1984; Tauber, 1972), it seems somewhat surprising that little work has been devoted of late to this highly relevant topic in marketing and the study of consumer psychology (see Atalay & Meloy, 2011; Lee, 2015; Rick et al., 2014 for recent exceptions). Despite the seeming dearth of investigation into the subject of retail therapy, much attention and energy has been devoted to the study of related topics such as emotion regulation, the role of affect and emotions in decision-making, and compensatory consumption, all of which have the strong potential to contribute significant critical pieces to solving the puzzle of retail therapy. Given our burgeoning knowledge in these related domains, the time seems ripe to assemble relevant findings from these otherwise largely disjointed domains to produce an integrative, holistic understanding of retail therapy.

In this work, we take a modest step in improving our understanding of the underlying drivers of therapeutic utility in shopping. Specifically, adopting a needs perspective while building on and synthesizing prior research on motivation theory, emotion regulation, and compensatory consumption, we propose a conceptual framework that illuminates the different sources of therapeutic utility in shopping based on four primary motives in consumption—affective-preservation, affective-growth, cognitive-preservation, and cognitive-growth. Importantly, our framework takes the view that therapeutic utility encompasses both hedonic utility and functional utility (even though the desire for retail therapy is typically motivated by the desire to repair one’s negative feelings), and that for retail therapy to be effective, consumers do not have to make any actual purchases.

Nonetheless, the framework that we have presented might raise a few important conceptual questions. First, is our framework complete? Second, is the categorization in this framework fluid? And third, does retail therapy always work?

With regard to the first question, at the outset, we have attempted to be as comprehensive as we could in conceptualizing the notion of retail therapy and consolidating the various sources of therapeutic utility in shopping. To achieve this, we have deliberately examined prior research that goes beyond the literature on shopping and retailing, and instead, build our framework upon motivation theories (e.g., McGuire 1974) in psychology to guide us in mapping out the various needs and motives that people may have in engaging in any activity, while looking at more specific empirical findings from several other literatures that are relevant to the subject of retail therapy. While striving to be comprehensive in our treatment of retail therapy, we are also guided by our goals to be concise and constructive in our conceptualization. Given that many aspects of shopping potentially satisfy both affective and cognitive needs, some amount of overlap and repetitiveness in our discussion of the various sources of therapeutic utility in shopping no doubt exists. Nonetheless, we believe that our framework presents a concise yet comprehensive depiction of the various mechanisms by which shopping affords positive therapeutic benefits.

The second question concerns the temporal sequence or co-occurrence of the different sources of therapeutic utility in our framework.5 We believe that the various sources of therapeutic utility are not mutually exclusive from a process perspective. First, it is indeed conceivable that a consumer’s needs and goals might change over the course of a shopping trip. Accordingly, the desired source of therapeutic utility might also change. For example, a consumer may initially engage in retail therapy to repair a general negative mood (affective-preservation) but, over the course of the shopping trip, realizes the psychosocial deficiency that drives this negative mood (cognitive-preservation). Second, consumers may also seek different types of therapeutic utility at the same time. For instance, a consumer might actively pursue the need to socialize (affective-growth) and the need to find inspiration (cognitive growth) during a trip to her favorite bookstore.

Finally, does retail therapy always work? Notably, our goal in this work is more descriptive than prescriptive or normative. We do not claim that shopping—whether buying or just mere window-shopping—is the panacea or always the most effective solution for mood repair. Rather, in this research, we aim to understand why retail therapy might work. Moreover, research has suggested a number of important boundary conditions that could limit the therapeutic effectiveness of shopping, a theme that we have noted throughout our discussion of the different sources of therapeutic utility (particularly in the Notes). Thus, in the service of consumer welfare, it seems prudent to pay attention to the conditions under which retail therapy would work and the conditions under which it would not.

Directions and Questions for Future Research

The present conceptual framework points toward several research questions that may be worthwhile for further exploration and examination. These questions can be broadly classified into three research directions, in order of increasing generality. In the remainder of this chapter, we discuss each direction and its related questions in detail.

1. Understanding the mechanisms of specific sources of therapeutic utility in shopping

Along with the various motives depicted in our proposed framework, we highlight and discuss numerous sources of therapeutic utility in shopping. Nevertheless, many of them can be examined more deeply with respect to their psychological underpinnings.

For example, one such source of therapeutic utility is the mere presence of other (unfamiliar) shoppers. Past research has demonstrated that people seek social affiliation when feeling down (Gray et al., 2011) and that the mere presence of others can influence preferences and consumer spending (Argo, Dahl, & Manchanda, 2005; Hui & Bateson, 1991; Maeng, Tanner, & Soman, 2013). At least two reasons implicate the potential therapeutic effects of being in the same physical space with unknown shoppers. First, similar to the dazzling display of brands, products, and sales signs in retail stores, the presence of other shoppers may act as a further source of distraction, distancing consumers from their negative emotions. Second, to the extent that spending unnecessarily (even in service of retail therapy) is deemed wasteful, seeing other shoppers browse and buy could provide the justification for consumers to shop and purchase as well while ameliorating feelings of guilt in spending. Future research could look into these mechanisms, among others.

Further, rather than merely discarding or forgetting about one’s negative emotions, could distraction also produce positive therapeutic benefits by giving consumers the space to construe their negative feelings or circumstances at a higher, possibly more positive level of construal (Chang & Pham, 2013; Trope & Liberman, 2003)? It seems plausible that stepping away from one’s negative feelings may allow one to put these feelings into perspective and “see the broader picture.” Similarly, it is conceivable that distractions and distancing may compel one to adopt an observer’s (vs. actor’s) perspective in treating one’s negative feelings, hence dissociating oneself from these emotions and leading one to focus on their cognitive drivers instead. The relationship between environmental distractions in retail and cognitive appraisal of one’s emotions could be further examined.

2. Comparing between different sources of therapeutic utility in shopping

Instead of viewing each source of therapeutic utility in shopping in isolation, future research could also juxtapose and compare different sources of therapeutic utility. In particular, studies could be conducted to assess their relative effectiveness and the conditions under which a particular source of therapeutic utility is more or less likely to drive shopping and spending decisions compared to other sources of therapeutic utility.

As an example, one of the foundational dichotomies of our proposed framework is the distinction between window-shopping and purchasing. Despite the general association of retail therapy with buying, this dichotomy highlights that even browsing without buying could generate therapeutic utility. However, it also raises a number of interesting questions. First, what are consumers’ perceptions of the relative effectiveness of browsing and buying in retail therapy? And what might account for these perceptions? Second, to what extent might shoppers still enjoy the therapeutic utility of window-shopping if their intention in seeking retail therapy is to make a purchase? Third, does the fact that both browsing and buying carry therapeutic utility imply that shoppers who buy would enjoy overall higher therapeutic utility from shopping, since they presumably would derive utility from both browsing and buying? In other words, are the various sources of therapeutic utility additive in nature?

Future research could also further analyze the personality traits and temporary psychological states of individuals who engage in different types of retail therapy. For example, regulatory focus theory (Higgins, 1997) distinguishes between two types of goal orientations: prevention focus and promotion focus; whereas prevention-focused individuals value safety and responsibilities, promotion-focused individuals value accomplishments and aspirations. These orientations seem to relate to the preservation motives and growth motives, respectively, in our proposed framework (McGuire, 1974). Would these conceptual mappings then imply that prevention-focused consumers would favor aspects of shopping that satisfy preservation motives, while promotion-focused consumers would favor aspects of shopping that satisfy growth motives? In particular, are promotion-focused consumers who aim to repair their negative feelings more inclined to seek variety, a behavior that is associated with greater cognitive-growth motivation than cognitive-preservation motivation (see Wu & Kao, 2011)?

Furthermore, past research has shown that the reliance on affect is more pronounced among people with a greater promotion focus than those with a greater prevention focus (Pham & Avnet, 2004; 2009). In one experiment (Pham & Avnet, 2009, Study 1), for instance, participants were more likely to base their evaluations of the contestants of the popular reality-television show, Survivor, on their affective qualities (e.g., friendliness, physical attractiveness) than their cognitive attributes (e.g., intelligence, hard work) when they were more promotion-focused. Extrapolating from these results, would affective (vs. cognitive) motives be stronger for promotion-focused (vs. prevention-focused) consumers in seeking retail therapy? Combining with the aforementioned discussion of preservation and growth motives (vis-à-vis regulatory focus theory), would affective-growth and cognitive-preservation motives be more dominant than affective-preservation and cognitive-growth motives in driving retail therapy? Understanding the chronic and situational factors that drive the preference for (and effectiveness of) different sources of therapeutic utility could help managers better understand their target market and design the most appropriate “customer journey” to encourage browsing and buying.

3. Examining retail therapy and therapeutic utility from a temporal perspective

Perhaps a somewhat conspicuous omission from the proposed conceptual framework for retail therapy is a time-related dimension. Adopting a temporal perspective in the study of retail therapy and therapeutic utility produces at least three questions that seem theoretically important for future research.

First, while retail therapy is typically assumed to be something that one seeks after one has experienced negative feelings, to what extent might consumers preemptively seek retail therapy in anticipation of future negative feelings and psychosocial deficiencies?

Some recent research suggests that retail therapy in service of future reparative needs is plausible. Kim and Rucker (2012), in particular, compare between the actions that consumers would take in proactive versus reactive compensatory consumption. They find that consumers who engage in consumption reactively (e.g., responding to a self-threat due to lower perceived intelligence) tend to increase consumption of both threat-related products (e.g., a dictionary set) and threat-unrelated products (e.g., a box of chocolate) for the purpose of distraction; in contrast, consumers who have the chance to engage in consumption proactivity tend to consume more when a product is threat-related rather than threat-unrelated, since the former product is more symbolically associated with the potential threat.

More pertinent to the subject of emotion regulation, some recent work in affect and decision-making (Faraji-Rad & Lee, 2016) demonstrates that people strategically “bank happiness,” such that they proactively choose to consume a positive-valence product option (e.g., listen to a happy song vs. a sad song) when they anticipate feeling sad later; this strategic choice arises from a lay belief that happiness is “bankable,” that it can be stored and consumed later in order to help one to better cope with the anticipated future negative feelings.

On the one hand, these recent findings suggest that strategic preemptive retail therapy is highly plausible. On the other hand, given that people are generally bad affective forecasters (Gilbert et al., 1998; Wilson & Gilbert, 2003), might people “overcompensate” and engage in too much retail therapy, possibly resulting in subsequent regret and buyer’s remorse? Thus, whether and how much preemptive retail therapy consumers may engage in seem to be worthwhile questions for future research.

Second, one way to think about the two previously discussed flavors of retail therapy (i.e., affect regulation and compensatory consumption) is that, in some cases, whereas negative affect can be likened to the symptoms that drive the desire for retail therapy, the cognitive reasons that prompt compensatory consumption can be likened to the underlying causes of these symptoms. Building on this distinction between symptoms and underlying causes, and our proposition that different aspects of shopping may satisfy different motives (affective vs. cognitive) in generating therapeutic utility, might some aspects of shopping (e.g., injecting positive feelings vs. shift in mindset) be more effective in the long run (i.e., “nipping the problem in the bud”)? Certainly, our ability to address these questions hinges on the more fundamental question of how the effectiveness of retail therapy can be measured (see Lee, 2015, Table 2.1, for a review of some measurement scales for retail therapy).

Finally, given that multi-channel shopping (i.e., consumers switching between different channels when shopping) is becoming increasingly prevalent (Neslin et al., 2014), future research could examine the implications of this market trend on retail therapy. In particular, online retailing and mobile retailing differ from traditional brick-and-mortar retailing in several important aspects. For example, digital channels generally provide access to a much wider variety of products than traditional, space-constrained retailing. Moreover, with more online/mobile shopping, while the amount of social interactions may increase due to the integration of social-networking sites, the quality of these interactions may deteriorate. Future research is needed to analyze how the types of therapeutic utility that these different channels offer differ, and whether consumers might choose particular channels strategically to maximize their therapeutic utility.

Conclusion

In this research, we propose an integrative conceptual framework that begins with the main classes of needs and motives that people have, and illuminates how different aspects of shopping—whether buying or mere window-shopping (without any purchase)—could satisfy these needs in achieving effective retail therapy. Based on the framework, it does seem that the potential sources of therapeutic utility in shopping are aplenty. Although we cannot claim to have found any answers to the curious question of whether shopping indeed leads to greater longevity, we are confident that we have taken a small but important step toward understanding the drivers of retail therapy, and sincerely hope that our work will spur more future research in this essential and relevant area within the study of consumer behavior.

Notes

1 McGuire’s original model includes a total of four dichotomies. However, this four-dimensional model is somewhat complex, and some of the dimensions (e.g., internal vs. external) in the model seem too detailed for our purpose and would generate unnecessary overlap among categories. Therefore, we focus only on the two main dimensions.

2 As discussed under “cognitive-growth motives” later, the excitement and sensory stimulation in retail environments may also satisfy consumers’ need for inspiration and to kill cognitive boredom.

3 While such behavior may be relatively harmless in isolation, repeated use of product purchases to reduce negative feelings, however, can lead to a deleterious habit that may result in compulsive buying disorder (Faber & Christenson, 1996; Faber & O’Guinn, 1992).

4 However, it is noteworthy that shopping with familiar others may lead a shopper to spend more as a result of social influence (Cheng et al., 2013; Mangleburg, Doney, & Bristol, 2004), especially when the shopper is agency-oriented (vs. communion-oriented) and high in self-monitoring (Kurt, Inman, & Argo, 2011), or perceives himself or herself to have been socially excluded, in which case the shopper may spend strategically in service of social well-being by, for example, tailoring his or her spending to the preferences of others (Mead et al., 2011). Even the mere presence of other shoppers can increase the incidence of impulse purchase because of social mimicry (Luo, 2005).

5 We thank an anonymous reviewer for proposing this question.

References

Adams, S. (2011, April 7). Daily trip to the shops “helps you live longer.” The Telegraph. Retrieved from www.telegraph.co.uk/news/health/news/8431898/Daily-trip-to-the-shops-helps-you-live-longer.html.

Anderson, J. R. (1995). The Architecture of Cognition. Psychology Press.

Argo, J. J., Dahl, D. W., and Manchanda, R. V. (2005). The influence of a mere social presence in a retail context. Journal of Consumer Research, 32(2), 207–212.

57Arnold, M. J. and Reynolds, K. E. (2003). Hedonic shopping motivations. Journal of Retailing, 79(2), 77–95.

Atalay, A. S. and Meloy, M. G. (2011). Retail therapy: A strategic effort to improve mood. Psychology and Marketing, 28(6), 638–659.

Atkins, K. G. and Kim, Y. (2012). Smart shopping: Conceptualization and measurement. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 40(5), 360–375.

Averill, J. R. (1973). Personal control over aversive stimuli and its relationship to stress. Psychological Bulletin, 80(4), 286–303.

Babin, B. J., Darden, W. R., and Griffin, M. (1994). Work and/or fun: Measuring hedonic and utilitarian shopping value. Journal of Consumer Research, 20(4), 644–656.

Babin, B. J. and Darden, W. R. (1995). Consumer self-regulation in a retail environment. Journal of Retailing, 71(1), 47–70.

Belk, R. W. (1988). Possessions and the extended self. Journal of Consumer Research, 15(2), 139–168.

Belk, R. W. (2013). Extended self in a digital world. Journal of Consumer Research, 40(3), 477–500.

Bellenger, D. N., Robertson, D. H., and Greenberg, B. A. (1977). Shopping center patronage motives. Journal of Retailing, 53(2), 29–38.

Bellenger, D. N., Robertson, D. H., and E. C. Hirschman. (1978). Impulse buying varies by product. Journal of Advertising Research, 18(6), 15–18.

Berger, J. and Heath, C. (2007). Where consumers diverge from others: Identity signaling and product domains. Journal of Consumer Research, 34(2), 121–134.

Blattberg, R. C. and Neslin, S. A. (1990). Sales Promotion: Concepts, Methods, and Strategies. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bloch, P. H., Ridgway, N. M., and Dawson, S. A. (1994). The shopping mall as consumer habitat. Journal of Retailing, 70(1), 23–42.

Bloch, P. H., Sherrell, D. L., and Ridgway, N. M. (1986). Consumer search: An extended framework. Journal of Consumer Research, 13(1), 119–126.

Bloch, P. H. and Richins, M. L. (1983). Shopping without purchase: An investigation of consumer browsing behavior. Advances in Consumer Research, 10, 389–393.

Bloch, P. H., Ridgway, N. M., and Sherrell, D.L. (1989). Extending the concept of shopping: An investigation of browsing activity. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 17(1), 13–21.

Borges, A., Chebat J. C., and Babin, B. J. (2010). Does a companion always enhance the shopping experience? Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 17(4), 294–299.

Brown, M., Pope, N., and Voges, K. (2003). Buying or browsing? European Journal of Marketing, 37(11/12), 1666–1684.

Cacioppo, J. T. and Patrick, W. (2008). Loneliness: Human Nature and the Need for Social Connection. WW Norton & Company.

Carver, C. S. and Scheier, M. F. (1990). Origins and functions of positive and negative affect: A control-process view. Psychological Review, 97(1), 19–35.

Chandon, P., Wansink, B., and Laurent, G. (2000). A benefit congruency framework of sales promotion effectiveness. Journal of Marketing, 64(4), 65–81.

Chang, H. H. and Pham, M. T. (2013). Affect as a decision-making system of the present. Journal of Consumer Research, 40(1), 42–63.

Chang, Y., Chen, R. C., Wahlqvist, M. L., and Lee, M. (2011). Frequent shopping by men and women increases survival in the older Taiwanese population. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 66(7). doi:10.1136/jech.2010.126698.

Chatterjee, P., Irmak, C., and Rose, R. L. (2013). The endowment effect as self-enhancement in response to threat. Journal of Consumer Research, 40(3), 460–476.

Chen, C., Lee, L., and Yap, A. (2017). Control deprivation motivates acquisition of utilitarian products. Journal of Consumer Research, 43(6), 1031–1047.

Cheng, Y. H., Chuang, S. C., Wang, S. M., and Kuo, S. Y. (2013). The effect of companion's gender on impulsive purchasing: The moderating factor of cohesiveness and susceptibility to interpersonal influence. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 43(1), 227–236.

Childers, T. L., Carr, C. L., Peck, J., and Carson, S. (2001). Hedonic and utilitarian motivations for online retail shopping behavior. Journal of Retailing, 77(4), 511–535.

Cialdini, R. B., Trost, M. R., and Newsom, J. T. (1995). Preference for consistency: The development of a valid measure and the discovery of surprising behavioral implications. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(2), 318–328.

58Cohen, J.B., Pham, M.T., and Andrade, E.B. (2008). The nature and role of affect in consumer behavior. In C. P. Haugtvedt, P. M. Herr, and F. R. Kardes, editors, Handbook of Consumer Psychology, pages 297–348. Psychology Press: New York, NY.

Cooper, J. (2013, April 2). Ebates survey: More than half (51.8%) of Americans engage in retail therapy—63.9% of women and 39.8% of men shop to improve their mood. Retrieved from www.businesswire.com/news/home/20130402005600/en/Ebates-Survey-51.8-Americans-Engage-Retail-Therapy%E2%80%94.

Corfman, K. P. and Lehmann, D. R. (1987). Models of cooperative group decision-making and relative influence: An experimental investigation of family purchase decisions. Journal of Consumer Research, 14(1), 1–13.

De Nisco, A. and Warnaby, G. (2014). Urban design and tenant variety influences on consumers' emotions and approach behavior. Journal of Business Research, 67(2), 211–217.

Dunn, E. W., Aknin, L. B., and Norton, M. I. (2008). Spending money on others promotes happiness. Science, 319(5870), 1687–1688.

eHealth. (2015, February 5). Health insurance & retail therapy: An Infographic. Retrieved from https://resources.ehealthinsurance.com/affordable-care-act/wish-retail-therapy-covered-health-insurance-infographic.

Eroglu, S. A., Machleit, K., and Barr, T. F. (2005). Perceived retail crowding and shopping satisfaction: The role of shopping values. Journal of Business Research, 58(8), 1146–1153.

Faber, R. J. and Christenson, G. A. (1996). In the mood to buy: Differences in the mood states experienced by compulsive buyers and other consumers. Psychology & Marketing, 13(8), 803–819.

Faber, R. J. and O’Guinn, T. C. (1992). A clinical screener for compulsive buying. Journal of Consumer Research, 19(3), 459–469.

Faraji-Rad, A. and Lee, L. (2016). Banking Happiness. SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2728061

Falk, P. and Campbell, C. (1993). The Shopping Experience. Sage Publications: London.

Festinger, L. (1957). A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Stanford University Press.

Filiatrault, P. and Ritchie, J. B. (1980). Joint purchasing decisions: A comparison of influence structure in family and couple decision-making units. Journal of Consumer Research, 7(2), 131–140.

Ganesh, J., Reynolds, K. E., Luckett, M., and Pomirleanu, N. (2010). Online shopper motivations, and e-store attributes: An examination of online patronage behavior and shopper typologies. Journal of Retailing, 86(1), 106–115.

Gao, L., Wheeler, S. C., and Shiv, B. (2009). The “shaken self”: Product choices as a means of restoring self-view confidence. Journal of Consumer Research, 36(1), 29–38.

Geuens, M., Vantomme, D., and Brengman M. (2004). Developing a typology of airport shoppers. Tourism Management, 25(5), 615–622.

Gilbert, D. T., Pinel, E. C., Wilson, T. D., Blumberg, S. J., and Wheatley, T. P. (1998). Immune neglect: A source of durability bias in affective forecasting. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(3), 617–638.

Grandey, A. A. (2003). When “the show must go on”: Surface acting and deep acting as determinants of emotional exhaustion and peer-rated service delivery. Academy of Management Journal, 46(1), 86–96.

Gray, H. M., Ishii, K., and Ambady, N. (2011). Misery loves company: When sadness increases the desire for social connectedness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37(11), 1438–1448.

Gregoire, C. (2013, May 24). Retail therapy: One in three recently stressed Americans shops to deal with anxiety. The Huffington Post. Retrieved from www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/05/23/retail-therapy-shopping_n_3324972.html.

Gregory, S. (2011, April 11). To live longer, granny, get your fanny to the mall. Time. Retrieved from http://healthland.time.com/2011/04/11/to-live-longer-granny-get-your-fanny-to-the-mall/.

Gronmo, S. (1988). Compensatory consumer behaviour: Elements of a critical sociology of consumption. In P. Otnes, editor, The Sociology of Consumption, pages 65–85. Solum Forlag: Norway.

Gross, J. J. (1998). The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Review of General Psychology, 2(3), 271–299.

Gross, J. J. (2014). Emotional regulation: Conceptual and empirical foundations. In J. J. Gross, editor, Handbook of Emotion Regulation, pages 3–22. Guilford Press: New York, NY, 2nd edition.

Groth, M., Hennig-Thurau, T., and Walsh, G. (2009). Customer reactions to emotional labor: The roles of employee acting strategies and customer detection accuracy. Academy of Management Journal, 52(5), 958–974.

59Hart, T. (1998). Inspiration: Exploring the experience and its meaning. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 38(3), 7–35.