Learning to write about your thoughts and feelings, especially to begin with, can be helpful. Here are some of the reasons why.

Thoughts forms offer ways of helping us to organize our thoughts and to distinguish between situations that trigger our feelings and moods, the kinds of thoughts and feelings that pour through our minds (often in a chaotic way), and then how we can re -focus our attention on generating helpful alternatives. Thought forms are just useful guides to help our practice and develop our minds: see Appendix 1 for some ideas.

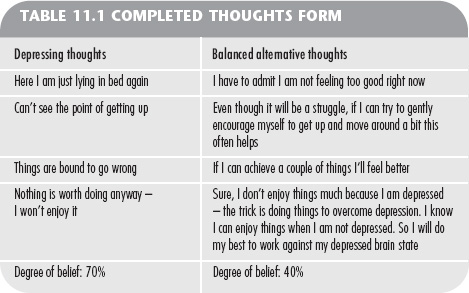

My advice here is: keep it simple. Use whatever kind of form suits you, rather than struggling with something that you find too complex – provided it does the job, of course. The most basic thought-alternative form is simply a page divided into two columns. You write your unhelpful, threat-focused thoughts in the left-hand column, and helpful, compassionate alternatives in the right-hand column. These depressive thoughts might be triggered by an event, or might come on as your mood dips. The key point is catching what these thoughts are and offering a balanced and compassionate alternative to them.

Table 11.1 shows an example of a completed form.

You will see that at the bottom of each column in this example there is a figure for ‘degree of belief’– that is, how much do you believe what you have written down? Some people find that if they rate how much they believe something this can be helpful for seeing that beliefs are not black and white, all-or-nothing. As time passes and you start to feel better you’ll be able to look back and see how the strength of your beliefs has changed with your recovery. Other people don’t find this particularly helpful, because they feel it is artificial in some way. Once again, find what works for you.

You can make up your own column headings for different tasks. For example, sometimes it can be useful to write down in two columns (1) the reason why you believe and then (2) in the other column the reasons to change that view, or consider the advantages and disadvantages of a particular belief. You might prefer to label the two columns ‘what my threat- or loss-focused and/or self-attacking mind says’ and ‘what my rational and compassionate mind says’. For all these variations you can use the two-column format and simply change the headings to suit.

In the thought forms given in Appendix 1 you will see other columns. In addition to the two noted above, we also have a column for writing down any critical events that might have triggered your distressing thoughts and a column for describing distressing feelings. This helps to give you a more complete picture; it will help your progress if you can be clear on what kinds of things tend to trigger your change of mood, arouse negative thoughts and feelings, or what those emotions and feelings actually are.

It can sometimes be useful to rate the change in the strength of your beliefs and in your emotions after you have been through the exercise. For that, we might add a third column to the simple two-column form. Table 11.2 shows the same examples we used above, with the third column added on.

Try as best you can, with an encouraging, supportive (not bullying) tone in your mind to carry out your plan to get up and out of bed, move about and do something active, no matter how small. You might rate how you feel having done this, compared to how you were feeling before you started. Note the difference. You could even compare how you feel now with how you might feel if you had not done anything at all but stayed in bed. The point here is that the more you yourself see the value in these kinds of exercises the more you are likely to have a go.

Once you have got the basic idea of the importance of writing things down and slowing your thinking down, you are prepared to start working on your thoughts, feelings, and moods. However, the exact framework you choose to do this should be something you decide for yourself: it’s important that you are happy with the form you use.

Different forms will be useful for working on different things. I have started us off here with a fairly basic thought-recording form; but please tailor it to suit you. Experiment with these forms and try out designs of your own. However, always keep in mind the basic point of all this: that is, to help you stop hitting your brain with lots of negatives, to get a better perspective on things and start giving your brain a boost and some warmth.

Ideas for generating alternatives are given in Chapters 9–11 and throughout this book. In Appendix 1 there are also various worked-out examples to offer you some more ideas – but these are only ideas. Sometimes it is helpful to take a few soothing rhythm breaths and focus on your compassionate self or image. You are trying to shift the position in your mind to where your thinking comes from – stepping into the compassionate frame of mind, as it were – and then from that position (or mind) starting to think about alternatives. You can also imagine compassionately trying to help someone, such as a friend you care for, to think in a different, more balanced way. How might you focus on strengths and courage, on coping and getting through? What would your voice tone be like? The key is to shift position. You will be very familiar with what your threat, loss and critical mind says, because that part of you will be active a lot of the time, but can you tune in to your compassionate mind, attend to it and develop it? Writing things down can give you the space and distance to start to do this.

There is now increasing evidence that writing about our feelings, expressing and exploring our feelings in writing (so-called expressive writing)1 can be very helpful for some people. Indeed, we can put into words on paper things we might struggle to think about in our heads or express to other people. We will explore some types of writing here so that you can see which one helps you.

Choose what you want to write about: your life in general, or a particularly difficult time in your life that you had trouble coming to terms with, or problems that you are experiencing right now. The idea here is to express your thoughts and feelings on paper, writing about what has happened or is happening to you. Imagine that you’re writing to a very compassionate person who completely understands what you feel.

Sometimes writing like this may stimulate different feelings in us. Again the key here is to go step by step and explore what is helpful to you. If you feel that there are things that you really don’t want to face on your own, be honest about that and think about whether you want to obtain professional help to guide and support you, or talk to a friend. Remember all these exercises are intended to be helps and guides for you, and you’ll need to judge just how helpful they are for you.

Another approach to writing is to begin to think about yourself and your feelings from different perspectives. Because we use different aspects of our minds when we write, we can sometimes find that in the process of writing, new insights and meanings emerge in our minds that help us clarify things. Practising doing this can help you access aspects of yourself that may help you understand your feelings better, learn how to tolerate them without fear or worry of acting them out, and perhaps tone down more depression-focused feelings and thoughts. But keep in mind what I have said many times before – this is an invitation, a ‘try it and see’.

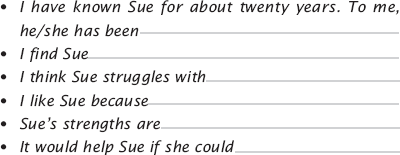

Sometimes it is useful to try shifting perspective on how we see ourselves. One way of doing this is to write a short letter about yourself, from the point of view of someone close to you who cares about you. I’m going to use the example of a fictitious person we will call Sue, but when you write your letter substitute your own name, of course. Such a letter might include:

This exercise is designed to help you develop the habit of considering other perspectives on yourself. If you like, show what you have written to someone you are close to and trust, and see what they think.

Some people find this very helpful, others do not. One person noted that ‘I actually don’t know anybody that well who would be able to write in detail about me.’ So here you might want to imagine a friend, and what you would like them to say about you. If you find it is too easy to dismiss positives then you might want to try practising some of the imagery exercises we talked about in Chapter 8, or the behavioral work in Chapter 12.

In this exercise we are going to write about difficulties, but from the perspective of the compassionate part of ourselves. There are different ways you can write this letter. One way is to get your pen and paper and then spend a moment engaged with your soothing breathing rhythm. Feel your compassionate self. As you focus on it, feel yourself expanding slightly and feel stronger. Imagine you are a compassionate person who is wise, kind, warm and understanding. Consider your general manner, voice tone and the feelings that come with your ‘caring compassionate self’. Adopt a kindly facial expression. Feel the kindness in your face before moving on. Think about the qualities you would like your compassionate self to have. Spend time feeling and gently exploring what they are like when you focus on them. Remember it does not matter if you actually feel you are like this – but focus on the ideal you would like to be. Spend at least one minute – longer if possible – thinking about this and trying to feel in contact with those parts of yourself. Don’t worry if this is difficult, just do the best you can – have a go.

When we are in a compassionate frame of mind (even slightly), or in the frame of trying to help a friend or someone we care for, we try to use our personal experiences of life wisely. We know that life can be hard; we offer our strength and support; we try to be warm and not judgemental or condemning. Take a few breaths then sense that wise, understanding, compassionate part of you arise. This is the part of you that will write the letter. So we write this kind of letter from a compassionate point of view. If thoughts of ‘Am I doing it right?’ or ‘I can’t get much feeling here’ arise, note or observe these thoughts as normal comments our minds like to make, but refocus your attention and simply observe what happens as you write, as best you can. There is no right or wrong, only the effort of trying – it is the practice that helps. As you write, create as much emotional warmth and understanding as you can. You are practising writing these letters from your compassionate mind.

As you write your letter, allow yourself to understand and accept your distress. For example, your letter might start with

I am sad. I feel distressed; my distress is understandable because . . .

Note the reasons, realizing your distress makes sense. Then perhaps you could continue with

I would like me to know that . . .

For example, your letter might point out that as we become depressed, our depression or a distress state can come with a powerful set of thoughts and feelings – so how you see things right now may be the depression view on things. Given this, we can try and step to the side of the distress and write and focus on how best to cope. We can write

It might be helpful to consider . . .

A second way of doing this is to imagine your compassionate image writing to you, and imagining a dialogue with them and what they will say to you. For example, my compassionate image might say something like

Gosh, the last few days have been tough. Isn’t it typical of life that problems arrive in groups rather than individually. It’s understandable why you’re feeling a bit down because . . . Hang in there because you are good at seeing these as the ups and downs of life, and that all things change, and you often say at least we are not in Iraq. So you have developed abilities for getting through this and tolerating the painful things.

You will note that the letter points to my strengths and my abilities. It doesn’t issue instructions such as, ‘You must see these things as the ups and downs of life.’ This is important in compassionate writing. You don’t want your compassionate letters to seem as if they are written by some smart bod who is giving you lots of advice. There has to be a real appreciation for your suffering, a real appreciation for your struggle and a real appreciation for your efforts at getting through. The compassion is a kind of arm round your shoulders, as well as refocusing your attention on what is helpful for you.

Here’s a letter from someone we’ll call Sally, about lying in bed feeling depressed. Before looking at this letter, let’s note an important point. In this letter we are going to refer to ‘you’ rather than ‘I’. Some people like to write their letters like that, as if writing to someone else. See what works for you but, over time, use ‘I’. You could read this letter and substitute ‘I’ for ‘you’.

Good morning Sally

Last few days have been tough for you so no wonder you want to hide away in bed. Sometimes we get to the point of shutdown, don’t we, and the thought of taking on things is overwhelming. You know you have been trying real hard, I mean you haven’t put your feet up with a gin and tonic and the daily paper. Understandably you feel exhausted. I guess the thing now is to work out what helps you. You’ve shown a lot of courage in the past in pushing yourself to do things that you find difficult. Lie in bed if you think that it can help you, of course, but watch out for critical Sally who could be critical about this. Also you often feel better if you get up, tough as it is. What about a cup of tea? You often like that first cup of tea. Okay, so let’s get up, move around a bit and get going and then see how we feel. Tough, but let’s try.

So you see the point here: it’s about understanding being helpful, having a really caring focus but at the same time working on what we need to do to help ourselves.

Another way to write these letters is to imagine the part of yourself you like, the self you would like to aspire to more of the time (as long it’s not the aggressive kick myself past of course!). Then try to bring that ‘you’ to mind – recall ‘you at your best’, ‘you as you would like to be’ and then write from that part of you.

When you have written your first few compassionate letters, go through them with an open mind and think whether they actually capture compassion for you. If they do, then see if you can spot the following qualities in your letter.

Depressed people can struggle with this to begin with, and are not very good at writing compassionate letters. Their letters tend to be rather full of finger-wagging advice. So we have to work and practise being compassionate. The point of these letters is not just to focus on difficult feelings but to help you reflect on your feelings and thoughts, be open with them, and develop a compassionate and balanced way of working with them. The letters should not offer advice or tell you what you should or should not do. It is not the advice you need, but the support to act on it.

Another way we can use letters is to express to ourselves our feelings about people. Usually these letters are not sent. If you feel you want to send them, it’s best to keep them for a week or two and think carefully before you do anything about it.

The purpose of this letter is again to articulate your feelings. You can write about your needs or sadness, disappointment or anger, or how you want to be loved or things you find it difficult to express. The point about writing these things down is that we think in a different way when we write.

Writing can help in ways that allow us to make sense of things and come to terms with them in a different way. For example, Kim felt very angry with her mother who was a career woman. As a child, Kim had been looked after by a number of different nannies. For some years Kim felt under pressure to tell her mother what she felt. She also felt she couldn’t have a genuine relationship with her mother until she cleared the air, and that she was being weak in not speaking honestly. However, we talked about this and the importance of taking the pressure off herself ‘to prove herself’ and confront her mother. She wrote some moving letters that were never sent, and at the end of the process felt that a lot of the pressure to confront her mother had gone. In a strange way this actually made it easier for her to think about having a conversation with her mother about the key issues. Kim came to see that the degree of anger she felt blocked her in many ways, because it was less about anger and more about wanting recognition from her mother that was important. The writing helped with the anger and then Kim was able to think about how to have a quieter conversation about the sadness in Kim’s life because of the effects of her mother’s career.

Sometimes if we are grieving it can help if we write letters to the dead person, saying goodbye or whatever else we want to say. Goodbye letters can sometimes be quite emotional but also helpful in articulating and expressing our feelings.

As with all these exercises, take one step at a time and only do things that are helpful for you, or that you can see will be helpful if you stick with them. If you feel you grief is overwhelming then this might be a time to think about professional help from a counsellor or psychotherapist. Or simply take very small steps, but do it reasonably often, and build up.

The last 10 years have seen a lot of research on forgiveness.2 However, there is a lot of misunderstanding about it. Forgiveness is about letting go of our anger. The person we forgive we may never like, never want to see. We might never condone their actions. Forgiveness is simply putting down our weapons and our desire for vengeance, and walking away. We say, ‘It ends here.’ Of course there may be a lot of thoughts such as, ‘I must not let them get away with it,’ ‘It is too unfair’, ‘I am weak if I do not pursue this,’ ‘If I were a proper person I would do something about this.’ The problem is that living with anger often isn’t going anywhere and that is very depressing. The only person we are hurting is ourselves and our brain, because we are constantly stimulating threat systems in our brain. Anger that is unhelpful like this simply makes us feel powerless.

Forgiveness is a way in which you can bring peace to your mind. We could fill a whole book looking at how to work on forgiveness.2 If you go on to the Internet you will be able to explore lots of sites on forgiveness. Check them out and see what works for you; some are interesting and helpful, and some not. But at a straightforward level, forgiveness letters are simply ways to help you acknowledge your anger and upset and forgive, let go, move on, walk away. As one patient told me:

I realized I had spent a lot of my life hating my mother and yet also wanting her to love me. She just wasn’t up to it. When I realized that actually she was quite a damaged person and simply wasn’t up to being as I wanted her to be, I felt more sorry for her and able to forgive her. To be honest I pulled back quite a bit and I think she would like me to have seen her more, but I found a comfortable distance for me. Recognizing this and letting go of my anger and my need set me free. And you know, wherever she is now (she died a few years ago), I genuinely hope she’s happy.

Importantly, keep in mind that the point of these letters is not to stir up difficult emotions but to be compassionate about them and learn how to think about them in compassionate and balanced ways.

So far we have rather focused on writing about difficult things. However research has also shown that it’s very helpful if we can spend some time thinking about things we appreciate, like and feel gratitude for.3 When we are depressed it can be quite difficult to have feelings of gratitude. Nonetheless if we focus on those feelings it will stimulate parts of the brain that are associated with positive antidepressant feelings. You can start by thinking of a person or key phase in your life, or someone who is showing you some kindness no matter how small, and think about gratitude. The feeling of gratitude is not a grudging or a belittling feeling at all, but a feeling of pleasure and joy that the other person was there and helped you in some way.

Gratitude is not associated with a feeling of obligation. The moment we feel obligated by somebody else’s kindness it is difficult to feel gratitude. Focus on the behavior. One patient noted that although there were things that angered her about her husband, just focusing on her gratitude for him helped her feel more balanced and happier.

The same goes for appreciation. Take your pen and a fresh sheet of paper, and write about the things you appreciate and like in your life. They might be quite small things like the first cup of tea of the day; the blue of a summer sky; certain tele vision programs; the warmth of your bed; a relationship; or part of your job – absolutely anything that gives you feelings of appreciation and liking. Notice how we often let these pass. Bear in mind why you are doing this as an exercise – it is to balance up your systems and to stimulate part of your brain that will help you counteract the feelings of depression. Recall that depression will force you into a corner of your mind so that you always have to walk on the shadowy side of the street, so we have to practise refocusing.