8

Switching our minds to kindness and compassion

This chapter explores some ways in which we can direct our thinking and attention to activate a soothing part of our brain. We’re going to be looking at developing kindness for ourselves and for others. Both these can really help our minds become more settled and cope better with life difficulties. However, some depressed people are actually resistant or frightened of the idea of being kind to themselves, even when this can help with depression. If this idea of self-kindness seems strange or threatening to you, just stay with it for a while and later we will explore your fears of becoming kind, understanding and compassionate to yourself. But it is always just a step at a time.

In this chapter we are going to use our imagination. Some of you might think, ‘Oh, I am not very good at imagining things, I have no imagination.’ Well, don’t give up on the idea yet, let’s have a go and see how far we can get. In fact, you don’t have to be good at imagining things; it’s the act of trying that is important. The key is trying to direct your attention and create things in your mind that are good for your brain.

What imagery isn’t

It is important to recognize that when we ‘imagine things’ we usually don’t see detailed pictures in our minds. Generally, images are fleeting and we get fragments and glimpses of things. For example, if I ask you to imagine your favourite meal, or the house you might like to live in, or what you will be doing tomorrow, you probably will not get a clear picture in your mind; more like fleeting impressions and feelings. When we talk about imagery we are really trying to create ‘a sense of’ as opposed to a ‘clear picture of’. It is about how we direct our attention, the focus of our minds. For all of the exercises below it’s really the effort to create things in your mind, in a certain way, that matters rather than the results, or having clear pictures in your mind.

Mindful imagery

When we do these exercises we do them mindfully (see Chapter 7), aware that our attention will wander. You might be able to focus for a few seconds and then your mind wanders off to various things you have done, think you should do, or want to do and so on. It does not matter if your mind wanders a hundred times, gently bring your attention back on to the task. The act of noticing and redirecting your attention is the important bit. If you find thoughts like ‘I can’t do this’, ‘I am not doing this right, I cannot feel anything’, notice these thoughts, and then gently and with kindness bring your mind back to what you’re trying to do. You will also notice that some days you will find it easier than others. In all these exercises there is no forcing or pushing oneself to do things. We simply put time aside to do the exercise, without judgement of whether it goes well or badly, because there is no well or badly (unless you make that judgement) – rather there is just ‘the doing’. Practice on a regular basis helps, of course, as it does for any skill we want to learn, be it playing golf, the piano, or painting – practice will help us improve.

Safe place imagery

The first imagery exercise we’ll do is about creating a place in our minds that we feel comfortable in. Let’s deliberately practise creating in our minds places that we find soothing, calming and where we want to be. To begin with, it is useful to start by sitting or lying down comfortably and going through your soothing breathing rhythm and a short relaxation exercise (see pages 123–5). If you don’t like the breathing exercise then sit quietly for a few moments. Then allow your mind to focus on and create a place that gives you the feeling of safeness, calm and contentment. The place may be a beautiful wood where the leaves of the trees dance gently in the breeze. Powerful shafts of light caress the ground with brightness. Imagine a wind gently on your face and a sense of the light dancing in front of you. Hear the rustle of the trees; imagine a smell of woodiness or sweetness in the air. Or your place may be a beautiful beach with a crystal blue sea stretching to the horizon where it meets the blue sky. Underfoot is soft, white fine sand that is silky to the touch. You can hear the gentle hushing of the waves on the sand. Imagine the sun on your face, sense the light dancing in diamond sparks on the water, imagine the soft sand under your feet as your toes dig into it and feel a light breeze gently touch your face. Or your safe place may be by a log fire and you can hear the crackle of the logs and the smell of wood smoke. These are examples of possible pleasant places that will bring a sense of pleasure to you, which is good – but the key focus is on feelings of safeness for you. They are only suggestions, and your safe place might be different.

When you bring your safe place to mind, allow your body to relax. Think about your facial expression; allow yourself to have a soft smile of pleasure at being here. It helps your attention if you practise focusing on each of your senses; what you can imagine seeing, feeling, hearing and any other sensory aspect.

It is also useful to imagine that as this is your own unique safe place, the place itself feels joy in you being here. Allow yourself to feel how your safe place has pleasure in your being here. Explore your feelings when you imagine this place is happy with you here.

When you become stressed or upset you can practise your soothing breathing rhythm for a few minutes and then imagine yourself in this place in your mind and allowing yourself to settle down, to give you some chill-out time. Keep in mind that we are using our imagery not to escape or avoid, but to help us practise bringing soothing to our minds. Keep in mind too that these are all what we call behavioral experiments for you to try out and see what happens inside you. You get your own evidence for what is helpful to you, and build on that.

Compassion-focused imagery

Compassionate colour

Sometimes depressed people like to start off with imagining a compassionate colour. Usually these colours are pastel rather than dark. Engage in your soothing breathing rhythm and imagine a colour that you associate with compassion, or a colour that conveys some sense of warmth and kindness. Spend a few moments on that. Imagine this colour surrounding you. Then imagine this entering through your heart area and slowly through your body. As this happens, focus on this colour as having wisdom, strength and warmth/kindness, with a key quality of kindness. It would help if you can create a facial expression of kindness as you do this exercise.

One patient noted when he used compassion to help him face up to difficult decisions, the colour he associated with it became stronger. He was good at experimenting and seeing what worked for him; listening to his own intuitive wisdom. He began to think about his compassionate colours as helping him with different things.

Compassion qualities

Compassion is ‘being sensitive to distress with a desire and commitment to try to relieve it’. It is also an openness to the desires to see self and others flourish, and taking joy in that flourishing. Compassion and warmth are not just distress-focused – but a commitment for creating ‘contented joyfulness’ too. We can see compassion in lots of different ways, for example as simple and basic kindness, openness and generosity. We can add to these the idea that compassion is also related to wisdom (it can’t be unwise), strength (it is not weak and indeed often helps us develop courage), warmth (linked to the feelings of kindness) and non-judgemental attitudes. In the next chapter we will look at these qualities and skills in more detail.

The flow of compassion

Compassion-focused exercises and imagery are designed to try and create feelings of openness, kindness, warmth and gentleness in you. You are trying to stimulate a particular kind of brain system through your imagery. We can do this in a number of ways, such as using our memory and also our imagination.

Compassion-focused exercises can be orientated in three main ways:

Now we are going to explore experiences for each of these three aspects. In all these exercises below it is your intentions and efforts that really matter. You may need to practise your feelings before they come naturally. So we can learn how to become compassionate because we try to practise thinking and acting compassionately, whereas the feelings may be harder to generate.

Becoming the compassionate self

The first set of exercises is focused on you practising generating feelings of compassion within yourself. Here we are going to work on your inner kindness and how to focus it, build on it, learn how to direct it and practise it. In a way we are going to use exercises that good actors use to create states of mind in themselves. For example, if actors want to convey anger or anxiety or sorrow, they try to create these feelings in themselves. Indeed when they ‘get into role’ it can actually change their bodies and physiology. If you get into an anger or anxiety role, your heart rate may go up. Imagining ourselves in a role, or as having certain feelings and thoughts, changes our physiology. We can use this well-known fact to create compassionate healing patterns in our bodies.

First, find a place where you can be alone and quiet. Now, gently, with your soothing rhythm breathing, if you can, imagine that you are a wise and compassionate person. Think about all the ideal qualities you would love to have as such a person. Imagine that you have them. It does not matter if you have these qualities or not in reality because we are simply imagining them. Research has shown that just imaging doing certain things changes our brains – and might actually make us better at that thing. Imagine that you have those qualities right now, in this moment. Imagine having great wisdom and understanding. Spend time imagining what that feels like.

Imagine having strength and fortitude. Spend time imagining what that feels like. Next imagine having great warmth and kindness and never being judgemental and again spend time imagining what that feels like. Think about what other qualities you’d like to have in your compassionate self. Imagine that you have them. Imagine your inner sense of calmness in your compassionate self that is based on wisdom. Try imagining each quality, noticing how that feels. Adopt a kind and gentle facial expression and spend time exploring that. Assume a body posture that feels compassionate to you, and spend some time exploring that too. You can also bring to mind ‘you at your best’, recalling a time you have felt calm, kind and wise. Breathe your soothing rhythm and focus on these memories and qualities.

Imagine the sound of your voice, your tone, pace and rhythm when you speak from this compassionate self. Imagine the emotion and feelings that are in you and are expressed in what and how you speak. You might imagine yourself as younger or older than you are now. Imagine yourself dressed in a certain way. I don’t know why, but for me I imagine having longer hair – it’s somehow associated with my image of a compassionate self. Maybe I am being kind to the fact that I am going bald!

Each day, put some time aside to ‘play with’ this role of being a ‘calm compassionate self’. Sometimes depressed people tell me that they’re like this already because they are kind to others. Indeed that might be so, but they can also be a bit submissive and do things they don’t really want to do because they want to be polite or they want to see themselves as a nice person and worthy of being loved (people pleasers). And that is perfectly understandable. However, the compassionate self we are thinking about here is not worried about what other people think. We have to distinguish true compassion and kindness from submissiveness.

Compassion under the duvet

Many meditation guides will advise you to spend time on your practice, perhaps sitting for 10 or 20 minutes a day. Tibetan monks may spend hours each day on their meditations. When we are depressed, that’s a bit tough! So let’s begin with what I call ‘compassion under the duvet’. When you wake up in the morning, or before you go to sleep, spend a moment or so with your soothing rhythm breathing, wearing a kindly expression and making a commitment to try as best you can, without judgement, to become a compassionate person. Focus on your kind facial expression. Imagine that you are a compassionate person and run through the exercise above.

Any time you have, such as waiting for a bus, or sitting on a train, or in a waiting room, or lying in the bath or walking – concentrate on your breathing and focus your attention on being a compassionate person inside yourself. These are times when our mind is often just idling along thinking all kinds of things, so why not use this time more productively to practise your exercises? You may find that if you practise every day, even if it’s only for a minute or two, the sense of compassion will actually stay with you more and more and you will want to practise more. Little and often can be very helpful.

Using your compassionate self

Different people find that they prefer to do things in a different order to that which is given here. Try for yourself and see what works for you. Perhaps focusing on compassion for others or developing your compassionate image (see below) is best for you as a starting place.

Wanting to be free of depression

When you feel you have the basic idea of imagining yourself as a compassionate being, and can notice but don’t engage (in fact smile at) all those thoughts that whisper in your mind, ‘No you’re not; you can’t do this; it’s not going to work you know,’ you can focus on a few key statements such as:

Focus on the desires in the words and your kindly facial expression. Feelings may come slowly with practice.

If you feel this is a bit overwhelming, pull back to focusing on just being a compassionate person; focus on your breathing, your facial expression and the tone of your voice. If you feel uncomfortable – say you feel you do not deserve compassion or for some other reason – then stay with the exercise for as long as you are able. You are slowly desensitizing yourself to fears and concerns about being kind to yourself. Try not to engage with arguments for or against in your mind – just do the exercise as best you can. If you feel very little, do not worry as the practice itself can be helpful – simply give some time to the exercise. Again, go at your own pace and explore how these ideas work for you. If this is still tough for you then you might want to start your practice with compassion for others (see below). If this is still difficult then there are other exercises throughout this book that you might get on with. The point is to try not to force anything – just be as mindful and open to possibilities as you can. It’s like sleeping – we can’t force ourselves to go to sleep, and if we keep checking ‘Am I nearly asleep now?’ it doesn’t help. We can only create the conditions where sleep may occur.

Developing self-compassion for the difficult parts of ourselves

We are now going to use this compassionate self and focus it on others and on ourselves. When you feel you have practised becoming the compassionate self a few times, and are beginning to get the hang of it, you can use this exercise to help you cope with difficult feelings or setbacks in your life. For example, imagine that you are angry but are also fighting with yourself about it. Sit comfortably for a moment and create your compassionate self. Remember to adopt suitable facial expressions. If you have been engaged in your soothing breathing, just have a sense of your body calming. Now imagine your angry self; see it a few metres in front of you. Look at the angry expression and note the feelings inside this angry part of you – the frustration or sense of injustice – feelings that are not very pleasant. Now feel compassion for the angry part of you that you can see in front of you. You are not trying to change anything, because you realize that anger is part of our human brain that can be powerful and unpleasant. To the best of your ability, send compassion to that anger you see in front of you. It can have as much compassion as it needs. Notice what happens if you just sit compassionately with your anger.

If you find your mind wandering, refocus it on your powerful compassionate qualities. If you feel you are getting pulled into the anger and starting to feel angry again, then break off, pull back and re focus on your breathing and becoming the compassionate self. See your compassionate self as the wiser, older, more rooted part of yourself – you at your best. When you feel back in that role then re-engage. Your sense of yourself should also stay in the compassionate position, so pull back and refocus if that slips. If you feel yourself become critical of yourself, then again pull back and refocus on being the compassionate self.

Notice how if you hold your compassionate position, somehow that can feel quite powerful because it comes from a position of wisdom, fortitude and strength. Explore that sense of powerfulness from this position. I chose anger as the emotion to focus on here because anger and frustration are often emotions depressed people struggle with. Another emotion you might wish to work with might be anxiety.

When you feel ready you can engage with ‘the depressed self’. Once again see this (depressed) self in front of you, and in your wisdom recognize our brains have been designed to allow depression, and that is not our fault. Life can be very hard and painful. The depressed self is only one of many selves and brain patterns. The most important thing is to practise having compassionate kindness towards this self rather than anger, contempt or fear. And this is not self-pity or feeling sorry for yourself, because compassion asks you to develop wisdom, strength and courage as well as warmth and kindness.

When you first focus on the depressed self you might feel pulled into the depressed self, and tearful. Pull back, and refocus on the compassionate self so that compassion grows in you – feel yourself expanding and becoming stronger based on wisdom and understanding. This may take time.

People’s experiences with this can be very different. One woman felt tearful and cried, but felt this connected her with important feelings. She felt better because she was able to end her sitting with a compassionate focus. Another woman started out okay, but then felt overwhelmed and could not hold the compassionate self position. She needed more practice. Another person become agitated and had to work slowly on the compassionate self. The key thing is not to be overwhelmed but to work at your own pace and explore what is helpful for you. Your goal is to become kind to yourself and understanding of your depression. In these exercises we are not trying to change the depressed self but take a compassionate stance towards it.

Happy self

Recall a time when you were happy. Looking through the eyes of your compassionate self, see yourself smiling, happy and feeling content. Let your compassionate self feel joy for the happy self. Notice what feelings come up when you focus on being ‘happy’ – strangely it might make you feel sad because happiness might seem a long way away! Or you might notice other resistances. If so, stay with these feelings as best you’re able and always pull back to just being the compassionate self if it feels overwhelming. The important practice here is creating in your mind the potential for happiness and self and support from the compassionate self. We can learn to imagine ourselves as ‘well’, ‘happy’ and free of suffering. You can extend to any other positive aspects of yourself that you wish.

Compassionate practice is not just with threat-based feelings but with positive ones too!

Compassion and kindness for others

In our next exercise we are going to imagine kindness flowing out. Some of you might find this an easier exercise than the one above, so might prefer to start here. There is now increasing evidence that if we practise trying to focus on compassion for others this stimulates key brain areas which are helpful in combating depression and anxiety.2

Recall a time when you felt very kind and caring towards someone (or if you prefer, an animal). Don’t choose a time when that person was very distressed, because then you are likely to focus on that distress. As in the experience of remembering somebody being kind to you, ensure that you have space to practise without distraction, sit comfortably and engage in your soothing rhythm breathing. Remember to create a kindly facial expression with (say) a slight smile. Notice your feelings in your body and the sense of yourself that emerges from such memories.

Next, bring to mind a person or people whom you want to feel you can help to be free of suffering. This may be a partner, a friend or a child. The idea is to practise filling your mind with compassion for another – you can choose who the other will be. Proceed with the following steps.

If you want to take this practice further, you can gradually expand the circle of people to whom you send your compassion – to friends and acquaintances, then to strangers and even to people you don’t like. They too have all found themselves here with a brain they did not choose and passions, desires and feelings they did not design, and are ignorant of the forces that operate within them. However, this is more advanced practice and if you are depressed you might want to start slowly and build up. The basis of the practice is to fill your mind with desires and feelings for all living things to be free from suffering and to flourish. If you can expand your practice time to, say, five and then ten minutes. Longer would be helpful, but any time you can give to practice is useful.

Being joyful in other people’s flourishing

In this exercise we are going to focus on creating what is called sympathetic joy, which is joyfulness in the flourishing and well-being of others.

Find a place where you won’t be distracted and can sit comfortably and engage in your soothing rhythm breathing. Do that for about one minute until you feel ready to engage in the imagery. Now try and remember a time when you were very pleased for someone else’s success or happiness. Perhaps it’s someone close to you in your family; seeing them do well made you very happy. Recall their facial expressions in your mind. Feel the joy and well-being in them. As you do this, focus on your own facial expressions and feel yourself expanding as you remember the joyfulness of that event.

Notice how this joyfulness feels in your body. Allow yourself to smile. Spend two or three minutes sitting with that memory. Then, when you’re ready, let the image fade and maybe write some notes.

In the next stage you can focus on your feelings of joy for the successes or relief from suffering of others, eventually expanding this to all living things.

Compassion flowing in

Imagining your ideal compassionate image

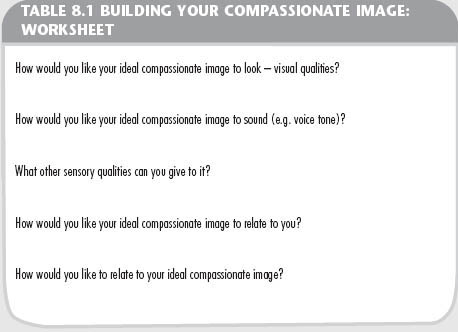

We are going to change the flow a bit. So far we have focused on your internal feelings of the compassionate self and being compassionate to different parts of you. Then we directed this to others and tried to fill our minds with kindness and wisdom. In the next exercises we are going to practise exploring our feelings as a recipient of compassion, by imagining another mind – wiser, stronger and warmer than our own – wanting us to be free of suffering and to flourish. I call this ‘imagining your ideal compassionate image’. Let’s now focus specifically on the ideal compassionate image that brings compassion for you. You can work on this using the worksheet on page 174.

The usual way we experience compassion is, of course, through the kindness of others. This usually flows in and through relationships. We can practise stimulating our soothing system by imagining relating to ‘compassionate others’. Just as we can imagine ideal meals or ideal sexual partners, that can stimulate our bodies and physiologies in specific ways (see page 28), so we can create inner images that can stimulate the soothing system. The idea here is to play with, create, discover, build and develop your compassionate imagery; experimenting with what works for you. In fact the idea of imagining a compassionate other, and practising and focusing our minds on that image, as a way to help ourselves develop emotionally and heal, is thousands of years old.3

Let’s think about how we might create a compassionate image that we can relate to using fantasy images. When you think of compassion, what kinds of images come to mind? Close your eyes for a moment and allow the word compassion or kindness to sit gently in your mind. What colours are associated with it for you? What sounds and textures? There is no rush. Maybe a mixture of colours and sounds come to mind.

In the next step we are going to focus on creating a specific image that you can feel has great compassion for you – that is ‘is sensitive to your suffering and has a deep wish to help you with it.’ The image that might arise could be of a person, but some people prefer animals, or even a tree or a mountain. Remember you might only get a fleeting sense of something (see pages 145–146). What are the qualities that you see as central to compassion? Spend a moment and think about that. It might be kindness, patience, wisdom, and caring. The act of thinking about compassion and its qualities helps you start to focus your attention on it. When you have had some thoughts of your own you can consider giving your image four basic qualities. We met them earlier, but let’s look at them in a bit more detail now. These qualities are:

1 Wisdom. Imagine that your compassionate image understands completely what it means to be a human being, to struggle, to suffer, to have rage, feel depressed, but also to have desires, to feel joy. It understands the evolved creation of our human minds with all their complex feelings, lusts, desires, happy and distressing thoughts, that can conflict inside us. It knows these are part of being human. Some people like the idea that their compassionate image has been through similar things to themselves but is now older and wiser; it understands you perfectly because it has been there itself. The image has a wise mind because it knows from experience, but has reached the point of inner peacefulness. This sense that it will have had the same feelings, conflicts, fantasies and emotions as you can be important as a source of kinship, and points (and can inspire us) to the ability to move on and develop.

In Buddhism certain images of compassionate others (called Bodhisattvas) are indeed like this. They have been fully human and subject to the same passions and desires, mistakes, aggressions, depressions and regrets as all of us, but through their training, study and practice have gained insight and developed compassion that has emerged from personal struggle and suffering.

2 Strength and fortitude. Give your image the ability to endure and tolerate painful things, but also the strength to defend and protect you if necessary. Imagine it as strong and courageous. As we will see later, sometimes compassion requires us to have courage. Sometimes, too, it requires us to be able to tolerate and not act on our more destructive thoughts and feelings, or learn to be assertive, or acknowledge we need to face things that we are perhaps frightened of facing.

3 Warmth and kindness. Imagine your compassionate image has warmth and kindness that radiates from and around it. This key quality is specifically there for you because this is your own unique image that you are creating and building.

4 A non-judgemental/non-condemnatory approach. Our compassionate image is never condemning, judging or critical. This does not mean it doesn’t have desires or preferences. Indeed, its main desire is for your well-being and flourishing. Nor does being non-judgemental mean it is happy to go along with whatever feeling or action you decide; but it won’t condemn you for it but rather invite you to understand your feelings and thoughts and choose a compassionate path – which at times can mean learning to be assertive.

So these are our key qualities that we are going to build into our compassionate image. The idea here is to create an image that is unique and special for you. The image is yours and yours alone. Keep in mind that it is your ideal and in that sense suffers from no human failings but is fully and completely compassionate every time because it embodies these qualities exactly. Note that the idea of it being ‘an ideal’ is that it is ideal to you (it may not be ideal to anyone else). You give it every quality that is important to you, just as if you thought about your ideal house, meal or car you would give it everything that you wanted and wouldn’t hold back. So it is with your ideal image; you imagine it to have every aspect of compassion that is important to you. Deborah Lee has referred to this aspect as your ‘perfect nurturer’ – somewhat parental-like and protective – and some people really like that idea. Others see compassion in different ways, say as a friend or mentor – so you can decide exactly what qualities it has. Again, these kinds of exercises are used by various therapists to help people.4

Some people like to use religious images, for example of Buddha or Christ. If these images are helpful then by all means use them, of course, but for the exercises we are doing here, create a new one just for you, because it also represents a creation of your mind; it is your inner sense of compassion that you are learning to give a voice to. Sometimes religious images can have associations that are not helpful – such as the concern that Christ might disapprove of sin – whereas the compassionate image we are developing here is never judgemental or punitive in any way.

Find somewhere to sit comfortably where you will not be disturbed, and decide if you want to use a CD of chants or music, or have (say) a water fountain on, or a candle or some other sensory aspect in the room. Later you may not want these additions, but they can be helpful to start with to create the mood. I know some pieces of music help me, but the choice of music can be very personal. Thinking about listening to and finding music that helps you and stimulates feelings of kindness and gentleness can itself be interesting and helpful.

Sit with eyes looking down or closed, and engage in your soothing rhythm breathing. When you feel that your body is now into the rhythm of breathing, start to imagine your ideal of compassion. Bring a slight, gentle smile to your face and consider the following questions.

On page 174 there is a worksheet you can use. If you want to do this exercise then go to the worksheet now, read through the instructions, then engage your soothing rhythm breathing for 30 seconds and see what (if any) image comes to you. The idea is to do it mindfully so that if your mind wanders off task, you just bring it back.

When you are doing this exercise, go into as much sensory detail as you can. For example, think about how old the image is (if it’s a human one), the gender, type of eyes. Can you see it smiling? Do you have a sense of the hair style and colour? Do you have a sense of its clothes and postures? Next, focus on the sounds, the tone of the voice. If it communicates with you, what would it sound like to you? If there are any other sensory qualities that you would like your compassionate image to have, bring them into your exercise. One person I worked with saw a tall and bushy tree. It had been there for a long time and she felt she could snuggle into its branches and feel protected.

Think about how you would like your image to relate to you. Some people would like the image to seem older and wiser and very protective. For example, the person who thought of the tree for her compassionate image focused on its protective aspects, feeling surrounded by its branches. Other people like the idea of imagining being cared for, or cared about. One person wanted their image to truly understand how painful and difficult certain aspects of her life had been and still were. Sometimes our image may be parent-like – it can have all the qualities of the parent we always wanted, completely loving, forgiving and admiring; taking pleasure in our being. It is interesting to imagine that your compassionate image has ‘pleasure in your being’. Notice those intrusive ‘Yes, but.’ thoughts when you do this. They are common and understandable but, in this exercise, bring your attention back on task.

Your image might be not so much parent-like but more mentor-like or friend-like. It might give you the feeling that you are a valued member of a team or part of a community. This can be useful to help you think about feelings of belonging, and the idea of being in some relationship to others pursuing similar goals. This is central in Buddhist practice – feeling on the same journey with all others, with some being ahead of you ready to help. Your compassionate image can help you feel that we are all part of the human race. Even if you are depressed, remember there are many millions of people who suffer depression. If you see yourself as inferior or bad in some way, or are filled with anger or worry, remember there are many millions of people who feel as you do because we all have the same kind of brain. It is so easy to feel isolated. When we feel depressed we can make an effort to open our hearts up to the fact that depression is sadly part of the human condition. Our depression puts us right at the heart of being human.

Relating to your image

You might also think about how you would like to relate to your image, how you would like to speak to it, the kinds of things you would want to communicate to it. Spend some time imagining talking to your image. After all, think how much time you spend imagining talking to other people, what you might like to say to them. Sometimes people can find it useful to talk out loud, explaining their feelings but, when you do this, imagine that you’re not talking to thin air but to a very compassionate, understanding other.

Keep in mind that we are using imagery, and the only source of these qualities is your own mind, so we are tapping your own inner wisdom about the nature of compassion. Keep in mind that you are using this exercise to put you in contact with com petencies and strengths within yourself. It is a way of contacting your own inner compassionate side; no one else can imagine it or create it like you can. This is for you – only you. Remember also that the images we have in our minds are not complete pictures; they are fleeting, impressionistic glimmers and glimpses. Do not worry if nothing clear comes to mind; just be aware that you are practising stimulating different systems.

Meeting your image

In some traditions of meditation imagery, such as Buddhist practices, there are a number of imagery exercises such as imagining a clear blue sky, and the emergence of a landscape with trees. One then imagines the Buddha under the tree and compassionately linking to the Buddha; imagining the Buddha sending compassion from his heart to your heart. At the end of the exercise the Buddha dissolves back into the landscape and the landscape dissolves back into a clear blue sky. This is to symbolize the emergence and dissolving of all things.2,3

A variation of this which can be helpful is to imagine meeting your image in your safe place (see pages 146–7). Occa sion ally people feel they don’t want anyone else in their safe place, compassionate or otherwise. Others, however, like the idea of meeting their compassionate image in this way. For example, if your safe place is by the sea you could imagine your image coming along the beach to meet you, smiling and being delighted to see you. Sometimes seeing the image moving towards you, or the face breaking into a smile, is helpful. Sometimes people like to imagine sitting next to their compassionate image and the image having a very concerned, thoughtful and understanding expression; or, if it is a nonhuman image, to have a sense of concern, kindness and wisdom emanating from the image to the self. These are things to experiment with and see what helps you.

Difficulties with an image?

If, over a period of time, you are struggling to create any sense of a visual image then it may be that sounds would be an easier focus for you. You might think about the sound of a compassionate voice: is it male or female, softly spoken or powerful? One person I worked with had an image of a Buddha dressed as an earth goddess. She never saw this image clearly but she just had a sense of nurturing and great warmth. She could focus on this image or sense when she was distressed.

Another thing you can try, if you are struggling to generate an image or sound or sense, is to look through magazines or on the Internet for pictures of compassionate faces or people, and then use them as a template to get started on your imagery. Research has shown that if people practise focusing on looking for suitable pictures they are gradually training their brain to pick up on these cues, and this can have an impact on their self-esteem.5

Some people are not so keen on creating their own ideal, rather than of there being someone who wants to be compassionate to them. One person I worked with noted that, ‘I guess in a thousand years we may be able to build robots that look, feel and sound like humans and can be extremely compassionate. However, I am not sure that would work for me.’ This person wanted to experience compassion but from someone who wanted to relate to him, rather than someone whom he had created. However, we built into the imagery that his compassionate image wanted to relate to him but needed to be ‘tuned into’. We can’t communicate by e-mail unless we first turn on the computer and set it up to receive messages. Imagery practice means beginning to open up to hear these messages from within us. The point is that we want to stimulate our minds in certain ways. Clearly, if you feel that because these images are not real they are not helpful, then this may not be the exercise for you – at least, not yet. As with all these exercises, you have to find what works best for you.

Some people (often those who have been abused or have had difficult childhoods) can find human images too threatening. Sometimes they prefer to have a compassionate image such as a horse, an eagle, a mountain or a tree. These are fine, provided they are imagined as having human-like minds. The only slight problem with them is that it can be difficult to imagine a gently smiling or concerned compassionate face. Imagining this kind of expression on the face of another individual can be helpful, because there are areas in our brain that pick up on those signals and respond to facial expressions.

The exact relationship you have to your image can vary. For example, as I have noted, some people like to imagine their image as almost parental and they obtain a sense of being cared about and nurtured in a parental way. Other people like to think of their image more as a guide or a guru that is not nurturing them like a parent but guiding them. Yet others like to imagine their image as a companion. A variation on this imagery work can be to imagine that there are many individuals who are trying to bring compassion to our difficult feelings and relationships. It is hard, but imagine being part of such a community who are seeking compassion and healing. You imagine yourself linked into (a part of) the community of individuals who are seeking to bring kindness to the harshness of the flow of life.

Sometimes it can be very interesting to change the gender of our image. This is perhaps a more advanced approach that you might want to explore when you feel okay with earlier ideas. Keep in mind that you can have different images if you wish.

Some people like to imagine the kindness and warmth of the compassionate image being focused as a kind of energy. People who use this approach have developed a form of working with images that they call HeartMath.6 This group of researchers has been studying various ways we can train ourselves to improve a physiological process called heart rate variability, and reduce our unpleasant emotions, by imaging compassion flowing into our heart region. You can find out more through the HeartMath website.

Grounding

We can use our compassionate imagery to stimulate certain patterns in our brain. As we will see in later chapters, we then want to use these patterns to help us. Sometimes this is to help us think things through in a kind and supportive way, or help us to engage in things that we find difficult. For example, supposing you have a difficult phone call to make. You can engage in the soothing rhythm breathing, spend a few moments imagining your safe place or compassionate image and it offering support for you. Then, from that state of mind, make your phone call. It’s not magic, but it might give you a little helping hand to create these states of mind before the phone call.

If you do find this kind of imagery helpful then it can be useful to ground your imagery. This means that you practise your imagery while at the same time holding maybe a smooth stone or crystal or some other object in your hand. Then you can carry this object in your pocket so that when you hold it, it links you to the image and the feelings that you have been practising. You might like to find or buy a smooth stone or object that feels soothing in the hand and hold it while doing your imagination exercise. We call this grounding. Ideally, use something that can be replaced if lost, especially if you often have holes in your pockets!

In various spiritual traditions, imagery and invocation exercises are associated with other sensory triggers and processes called mudras and mantras. Mudras are gestures, body postures and hand movements that are associated with particular processes. For example, if you practise your compassionate imagery sitting in a traditional meditative style, i.e. sitting cross-legged or (what is more comfortable for many people) sitting in a chair, then you may want to rest your hands in your lap with index finger and thumb touching. This gesture can be used when doing the compassion imagery so that by breathing and holding the index finger and thumb together you can recreate the feelings generated in the imagery session. For example, you might have been practising your compassionate image at home in the morning. You then set off to work and are waiting for a train. What you do is engage your soothing rhythm breathing, hold your fingers in the same way and bring to mind your compassionate image or create within yourself the sense of being a compassionate self. Don’t forget that relaxed posture, slight smile and facial expressions, of course. You can imagine radiating compassion to everyone around you on the station – those who are also caught up in the flow of life and the hustle and bustle even though they may not want to be there either. Which finger the thumb touches can have different meanings in Eastern traditions. You can look these up on the Internet and read all about them if you are interested. Have some fun!

Overview

In many ways these imagery exercises are doing what all authors and writers of fiction do – which is to create scenes and characters in our minds. The only difference here is that you are doing this mindfully and exploring the impact on you from a soothing, connecting, compassionate point of view. If you come across images that don’t work for you, then drop them. If you know that your images change, for example with (say) your menstrual cycle or some other cycle, go with the flow, provided it seems to connect with your soothing system.

Ultimately some people may find that they are attracted into the more traditional spiritual traditions and want their images to be traditional. The point about all of this really is not to get lost in complexity but to recognize the spirit and the purpose of your work. It is to help you stimulate patterns of activity in your mind that give you access to and help to develop a compassionate mind and a soothing mind. This takes practice; it takes time to recognize and work with a mind that is like a grasshopper, but if you stick with it you may find it is useful to you; you may find that you do indeed train your mind for compassion.

Fear of compassion

Some people recognize that they are simply not used to this way of thinking and it seems odd to them, but they can understand its value and the importance of practice. However, other people can be much more resistant. For example, they may feel they do not deserve to be kind to themselves, they may see it as a weakness, or a self-indulgence or even selfishness. If these beliefs are strongly held they can get in the way of practice. One way around this is to simply note these beliefs as common, but to practise anyway. Think about it like physiotherapy. If you had a weak muscle in your leg, perhaps as a result of injury, you wouldn’t tell yourself you don’t deserve to have a stronger muscle. Let’s build these qualities, and then if you decide you don’t want to use them, that’s up to you.

For some people kindness begins to touch them in a deep way and can make them sad and even tearful. This is because it touches an inner wisdom, a ‘knowing’ – which is that many of us wish to be cared for, cared about and feel connected to others, and depression is such an isolating experience that there is a yearning inside us for reconnection. Some people are unsure about kindness because their parents could be kind one day but horrible the next. For them feelings of kindness and horribleness are somehow mixed up together. As they begin to feel kindness, the feelings of horribleness come back as well. If you feel like this, keep your focus on the feelings of kindness, notice other feelings creeping in, smile gently and bring the attention back to exactly what it is you want to focus on. Only go with things you feel comfortable with.

Another major block to compassion can be anger. Depressed people can struggle with anger or even admitting they have anger (see Chapter 20). Others may have thoughts that it’s not kindness they want to develop, but to find a way to fight back, to stand up for themselves or even get their own back on people who have hurt them! For people who feel like this, doing compassion exercises can actually make them feel a bit ashamed of their anger because they feel if they are compassionate they shouldn’t feel angry. This is a misunderstanding of compassion. As we’ll see in our chapters on anger, being able to be honest, and to acknowledge and express assertiveness are actually skills, but denying our anger or rage, sulking or telling ourselves we are wrong to feel it, or blindly acting it out – is not compassionate. Recognizing how painful rage is, is compassionate. Coming to terms with the fact that angry rumination is harmful to us is compassionate; learning how to work with anger is compassionate.

So there are many and various reasons why people can be wary of compassion and we will address these concerns as we go.

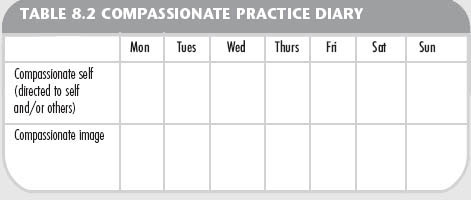

Overview and compassion practice

As in all things, practice will help you. To give you a plan and direction, try filling in the practice forms at the end of this chapter. These are really to focus you and give you an opportunity to reflect on your practice. Spend time with them if you can so that by the end of each week you can look back on what you’ve written on your practice imagery sheet.

As we go through this book we will be looking at your thoughts and behaviors. However, we will be doing this compassionately and you will often find that I suggest you create a gentle and kind position in your mind as you come to look at your thoughts and behaviors.