We now need to think about what we can do when we feel angry given that, in depression, anger is often related to hurt, vulnerability or feeling blocked. What are compassionate ways to express and deal with the things that are linked to our anger? One way is to develop assertiveness.

Research has suggested that assertiveness is related to many types of behavior. Willem Arrindell and his colleagues in the Netherlands suggest there are at least four components to it:1

1 Display of negative feelings. The ability, for example, to ask someone to change a behavior that annoys you, show your annoyance or upset, stand up for your rights, and refuse requests. This is what most people are thinking of when they talk about ‘being assertive’.

2 Expressing and coping with personal limitations. The ability to admit to not knowing or uncertainty about something rather than feeling ashamed to admit to it. Assertiveness also links to the confidence to acknowledge making mistakes, and to accept appropriate criticism. This aspect of assertiveness also covers the ability to ask others for help without seeing this as a personal weakness.

3 Initiating assertiveness. The ability to express opinions and views that may differ from those of others, and to accept a difference of opinion between oneself and others.

4 Positive assertion. The ability to recognize the talents and achievements of others and to praise them, and the ability to accept praise oneself.

Assertiveness is practising how to be open and honest as well as able to offer personal views and values and reach out to others. Assertiveness takes practice, and we can feel more confident in some situations and with some people than with others.

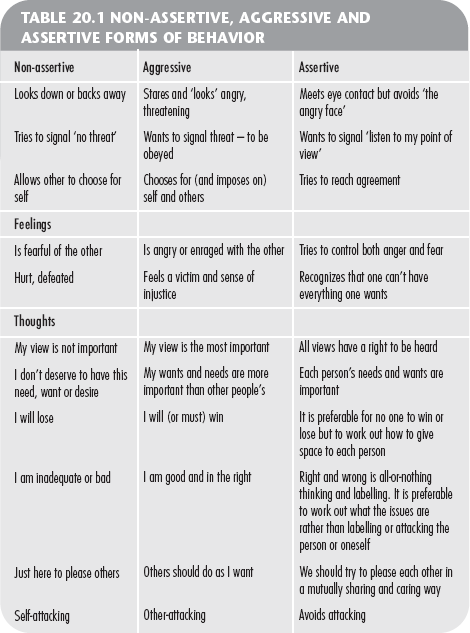

When people have problems in acting assertively, they are either highly submissive, fearful and prone to back down when faced with conflicts, or may become overly dominant and aggressive. Table 20.1 outlines some differences between non-assertive, aggressive and assertive forms of behavior, showing the contrasts in non-verbal behavior, feelings and thoughts.

Interestingly, non-assertive (submissive) and aggressive people can share similar beliefs. For example, both can think in terms of winners and losers. Aggressive people are determined not to lose or be placed in subordinate positions – ‘I’m not going to let them win this one’. Depressed people can feel that they have already lost and are in a subordinate position – ‘I can’t win’, or ‘I always lose’. Sometimes this seems like a replay of how they experienced their childhoods. Parents were seen as powerful and dominant and they (as children) felt small and subordinate. Depressed people can, however, be aggressive to those they see as subordinate to themselves (e.g., children). The important thing is to remind yourself that while it might have been true that, as a child, you were in the subordinate position, you don’t have to be now. You can look after yourself and treat others as your equals. You are an adult now. You might use the motto, ‘That was then. This is now’.

One way to feel more equal to others is to notice the ‘all or nothing’ of your thinking (powerful/powerless, strong/weak, winner/loser) and by considering that, ‘It is not me against them. Rather, we each have our own needs and views’. To be assertive, then, is to not see things in terms of a battle, with winners and losers. This may mean that you have to be persistent but not aggressive. The angry-aggressive person wants to win by force and threat; the assertive person wants to achieve a particular end or outcome and is less interested in coercing others or frightening them into submission – and will often accept a fair compromise.

A second aspect of assertiveness is that it focuses on the issue, not the person. To use a sporting metaphor, it involves learning to ‘play the ball, not the player’. In this case we speak of our wants or hurts without alarming others or employing condemning styles of thinking. For example, these are typical responses of someone who is angry and aggressive towards someone else:

Of course we might all think these things, and say them too, but the point is to maintain our wish to find more compassionate ways to deal with things that upset us. Don’t blame yourself, but refocus on your goal. Note that all these statements attack the other person, rather than addressing a specific issue or behavior. When people feel attacked, they tend to go on to the defensive. They lose interest in your point of view and are more concerned with defending themselves or counter-attacking. The assertive response focuses less on threatening or attacking the other person but more on specific issues, explaining our feelings and concerns and the quality of our relationships with others. Thus, in acting assertively we would explain in what way a particular action or attitude is hurtful. For example:

Can you see the steps here?

1 Acknowledge your anger.

2 Recognize in what way you feel hurt (and, of course, try to discover if you might be exaggerating the harm or damage done).

3 Focus on what this hurt is about and your wish to have the other person understand your feelings and your point of view.

4 Don’t insist that the other person absolutely must agree with you.

In assertiveness, we remain respectful of the other person. Winning, getting your own back or putting the other person down can have a negative outcome. In fact, even if you are successful (i.e. you win), the other person may just feel resentful and wait for a chance to get their own back on you! Winning can create resentful losers.

One word of warning. When you acknowledge your hurts assertively, this doesn’t include making the other person feel guilty or ashamed. Sometimes people don’t want to share with others what they want to change, but just want to make the others feel bad. When they discuss the things they want to change, they do it in a rather whining, ‘poor me’ way. Or they may say, ‘It’s all your fault that I’m depressed’. They may think, ‘Look what they’ve done to me – I’ll make them feel guilty for that. Then they’ll be sorry.’ This is understandable but not helpful. Getting your own back by trying to make people feel guilty is not being assertive. You may at times wring concessions from others, but usually people feel resentful if they have to give in because they have been made to feel guilty. I am sorry to say that some depressed people can do that – and children of depressed parents testify to it. All we can do here is be honest and try to spot our unhelpful behavior and change it.

Sometimes we might even do things to ourselves to try to make the other person feel guilty. After an argument with her mother, Hilary went home and took an overdose. Later she was able to recognize that she had been angrily thinking, ‘She’ll be sorry when she sees what she made me do’. Nobody can make us do anything – short of physical coercion. It was Hilary’s anger that was the problem. Her mother had been critical of her, but at the time Hilary had not said anything, although she had felt anger seething inside her. Her overdose was a way of trying to get her own back. With some courage and effort, Hilary was able to be assertive with her mother and could say things like: ‘Look, Mother, I don’t like the way you criticize me. I think I’m doing an okay job with my children. It would help if you focused on what I do well, not on what you think I do badly.’ This took her mother aback, but after that, Hilary felt on a more equal basis with her mother.

Sometimes depression itself can be used to attack others. Hilary also came to realize that, at times, she did feel happy but refused to let others know it. She wanted to be seen as an unhappy, suffering person, and that this was other people’s fault and they should feel sorry for her and guilty. It was also an attempt to evoke sympathy from others – although it rarely worked. She had the idea that, if she showed that she was happy, she would be letting others off the hook for the hard times she had had in the past.

Sometimes there is a message in our depression. It may be to force others to look after us, or it may be to make them feel sorry for us. We find ourselves turning away from possible happiness and clinging to misery. Somehow we need someone to recognize our pain, apologize, or maybe feel sorry for us or rescue us – and we are not going to budge until someone does. It can be helpful to think carefully about how you want others to respond to your depression. It can be a hard thing to do, and you might see that sometimes we use our depression to get our own way or get out of doing things. Try not to attack yourself about this; you are far from alone in doing it. Your decision is whether to go on doing it or whether you can find other ways to make your voice heard. Using your own rational and compassionate mind can help you move forward.

Another non-assertiveness problem is sulking, or passive aggression. In sulking, we don’t speak of our upsets but close down and give people the ‘silent treatment’. We may walk around with an angry ‘stay away from me’ posture, or act as if we are really hurt, to induce guilt. Indeed, our anger is often written all over our faces even as we deny that we feel angry. We have to work out if our sulking is a way of getting revenge on others and trying to make them feel guilty. Are we sulking in order to punish others? Always be kind to your sulking – but recognize it as a rather stuck state. Try to work out why you act that way. What stops you from being more active and assertive? What would you fear if you changed and gave up sulking?

You may feel powerless to bring about changes. This may be because you believe that direct conflict would get out of hand, or to show anger is to be unlovable, or because you think you would not win. However, sulking does have powerful effects on others. Think how you feel when someone does it to you. The problem with sulking is that it causes a bad atmosphere and makes it difficult to sort out problems. When you sulk, you give the impression that you don’t care for others. Sulking is likely to make things worse. Another problem is that sulking often leads to brooding on your anger. The more you do this, the more you will want to punish others.

You’ll find that, if you can learn to be assertive and explain what it is that you are upset about, you will feel less like sulking. It might be scary, but the more assertive you are rather than sulking, the more powerful you will feel. If in a sulk, be mindful – stand back from your feelings and how your body is pushing you to act and see what happens if you view those feelings compassionately – don’t fight ‘the sulk’ but compassionately steer your way out.

A common occurrence is that we can become angry with ourselves for not being assertive. We have probably all had the experience of getting into a conflict with someone and not saying what we wanted to say. Then later, maybe going over it in bed that night, we feel very cross for not standing up for ourselves. We feel that we have let the other person win or get away with something. Afterwards we think of all kinds of things that we could have said but didn’t think of at the time. Then we start to brood on this failure to be assertive and our self-criticism can really get going.

Roger was criticized in a meeting, which he felt was mildly shaming. He actually dealt with the situation quite diplomatically but, in his view, did not defend himself against an unfair accusation. Later that night and for a number of days afterwards he brooded on his failure to say what he had really wanted to say. These were his thoughts about himself:

Roger had a strong ideal of himself as a ‘person to be reckoned with’, but of course, he rarely lived up to this. As in the case of Allen (discussed on pages 457–8), who had to take early retirement, when Roger was out of the situation he started to activate his own internal fight/flight system and brooded on what he wished he had said. At one point, he had fantasies of revenge, of physically hitting the person who had criticized him. As with Allen, Roger’s thoughts led to some agitation.

The following are alternative coping thoughts that Roger could have considered:

You will be aware by now that the most damaging aspects of Roger’s internal attack were the thoughts of having failed and labelling himself as weak. These thoughts placed him in a highly subordinate position and were quite at odds with his ideal self (see next chapter). They activated a desire for revenge. Because of the way our brains work, it is quite easy to get into this way of thinking if we feel that someone has forced us into a subordinate position. We have to work hard to be compassionate with ourselves. Here are some alternative coping thoughts that can interrupt this more automatic subordinate thinking style:

Read these through again but this time with as much warmth and understanding as you can muster. Do you notice how it feels when you put warmth into it? If we approach the problem compassionately and think about what would be helpful, we might identify a need to use assertiveness. We could then plan what we wanted to say (but didn’t) and calmly try it out. The problem for Roger was that he never tried assertiveness but only felt disappointed with himself and then became angry. He never gave himself the chance to improve his assertiveness.

You can use these basic ideas in all kinds of relationships, including of course close ones.

There is much research showing that learning forgiveness, and working through the difficulties of forgiving, helps our mental health.2 If we carry a lot of anger for people we feel have hurt us in the past then this anger can sit in our minds and we often return to it – constantly stimulating our threat system. Deciding to walk the path to forgiveness can be a major way of moving forward. There are many aspects to forgiveness that we need to clarify. One cannot ‘make’ oneself forgive and sometimes we need time to heal – so no ‘I should’ or ‘I ought’ here. Forgiveness is about taking the steam out of one’s anger to others and in so doing no longer filling one’s mind with angry, vengeful or victim thoughts. It is not about liking, wanting to, or feeling one should want to see or relate to the person you forgive. It is not about accepting that their behavior was okay when it was not. Forgiveness does not mean that what happened in the past does not matter, or forgetting. Rather, it is the effort made to give up the desire for revenge or punishment. In brief, these stages are:

If forgiveness is an issue for you, it may be helpful to put time aside where you will not be disturbed, engage in your soothing breathing rhythm and then bring to mind your compassionate self or compassionate image(s) (see Chapter 8). Then gently work through each of the above phases. Make notes to yourself about your thoughts and feelings. You might like to write a compassionate letter to yourself on the benefits of forgiving and fears and blocks of forgiving.

Forgiveness can be a lengthy process requiring the acknow -ledgement of much hurt. Some people may try to forgive without acknowledging their own pain and anger, but when they do this, resentment usually remains. Forgiveness can be a painful process. Learning how to forgive is about learning how to let go of anger. A need for revenge can be damaging to ourselves and our relationships. We may tell ourselves how justified we are to be angry regardless of how useful this is.

Judy felt much anger against her parents for their rather cold attitude, and blamed them for her unhappy life. In doing this, she was in effect saying to herself, ‘I cannot be better than I am because my parents have made me what I am. Therefore, I am forever subordinate to them – for they held the power to make me happy. Therefore, I can’t exert any power over my own happiness.’

Gradually Judy came to see that it was her anger (and desire for revenge) which locked her into a bad relationship with her parents. Forgiveness required a number of changes. First, she needed to recognize the hurt she felt, which to a degree was blocked by her anger. Second, she needed to see that she was telling herself that, because her parents were cold towards her, she was ‘damaged’ and destined to be unhappy – that is, she was giving up her own power to change. She realized that she felt a ‘victim’ to her childhood. Rather than coming to terms with this, she felt subordinated and controlled by it. While it is obviously always preferable to have had early loving relationships, it is still possible to move forward and create the kind of life one wants. As Judy came to forgive her parents (but not condone them), she let go of her anger and felt released from the cage in which she had felt trapped.

When we forgive, we are saying, ‘I let the past go and am no longer its victim’. One patient said that, by giving himself the power to forgive, he was giving himself the power to live. Forgiveness is not a position of weakness. Some people find that ‘letting go’ feels like a great release. Remember you may never like or want a relationship with the person you forgive – rather, you let go of your anger.

We looked at self-forgiveness in the last chapter but because it is so important for us let us look at this once again. Self-forgiveness can go through the same phases as forgiving others:

Forgiving ourselves means that we treat ourselves with compassion. We do not demand that we are perfect or don’t make big mistakes from time to time. There are many spiritual traditions that recognize the great importance of forgiveness.

Some depressed people also have difficulty in reconciling and making up after conflicts have taken place. Couples and families with high levels of conflict but with good reconciling behaviors, and who value each other, tend to suffer less depression. When we reconcile and make peace, our anger and arousal subsides. Chimpanzees, our nearest primate relatives, actually seem better at reconciling their differences than some humans. Research shows that, after a conflict, they will often come together for a hug and embrace and they rarely stay distant for long.

So why is it difficult for some people to reconcile and make up? Some typical unhelpful thoughts that can make reconciliation difficult include:

In some cases, it is because as children we were never taught how to do it, and now as adults, we feel awkward about it. Perhaps neither they nor their partners know how to make the first move to make peace. Another reason is that one or both parties in the conflict will not reconcile until they are given the dominant position: they must win, get their own way and assert their authority. The one who reaches out to make peace is perceived as the one who has submitted.

For example, Angela said that, when she was a child, it was always her and not her mother who had to say she was sorry. If she didn’t, there would be a very bad atmosphere between her and her mother, which she found intolerable. Her mother would sulk, sometimes refusing to speak to Angela until she had apologized. When she did, her mother would remind her of the conflict and how naughty Angela had been. At a time when Angela was reaching out for acceptance, her mother would make her feel bad, ashamed and guilty again. Angela developed an expectation that, if she apologized, the other person would use this to make her feel bad about herself and would not accept her peace-making efforts without ‘rubbing her nose in it’. She was therefore very frightened of conflicts because there was no way she could reconcile afterwards without always feeling in the wrong.

There are various alternatives to the above unhelpful thoughts and ideas. For example:

Reconciliation, like much else in assertiveness, is a skill that can be learned. It may be difficult at first, but if you set your mind to it, you will improve. Learning how to make up after conflicts makes them less frightening. It helps us stop ruminating on the anger and conflict and building up the other person into a real ogre! You learn that you can survive conflicts, they are a normal part of life and we may actually benefit from them. Making up is only a submissive position if you tell yourself it is.

Reconciliation in intimate relationships may involve hugs and other physical contact, but of course, you can’t force this on others. If others are not ready to reconcile, all you can do is to state your position – that you’d like to make up. Be honest and offer an apology if you need to, and wait for the other person to come round in their own time. If they don’t, avoid getting angry with them because they don’t wish to go at the same pace as you.

One other thing that men especially need to be cautious of is encouraging their partners to prove that they are now reconciled with them by agreeing to have sex. If you do this, it is possible that your efforts at reconciliation will not be seen as genuine, but only as a tactic to get your own way. If your partner does not want to have sex, you may read this as ‘Well, she does not really care for me, otherwise she would’. This can lead to anger and resentment again. If you feel that there is not enough sex in your relationship, this is best sorted out at some other time, calmly, and with no threat of ‘If you loved me, you would’.

Feelings of anger and powerlessness can haunt you in depression because they stimulate the threat system. When that happens, the levels of stress hormones in our bodies increase. Healing then is about learning how to work with the feelings of anger and powerlessness, by being honest, learning assertiveness if we need to (and this may take some practice) and learning forgiveness. These are not easy steps, and in many spiritual traditions they can be seen as lifetime guides. If you practise developing your compassionate self, and really orientate towards developing that within you, this may help you in these tasks.