Humans are able to think about themselves as if they were thinking about someone else. We have feelings and make judgements about ourselves; there can be things that we like or dislike; we have relationships with ourselves that can be healing or unhelpful and even abusive. If we are honest we can think or say things to ourselves, and feel emotions (anger and contempt) towards ourselves, that we wouldn’t dream of directing towards other people. We recognize that if we treated others like that it would be abusive. But we treat ourselves like that, especially if we fail in some way, make mistakes, do things we regret, or just feel bad. At the times we need compassion, we actually give it to ourselves least. Because we believe that somehow being critical, harsh, disliking or even hating ourselves is deserved or can be good, we continue to do it. However, self-criticism, especially feelings of anger, frustration or self-contempt, is bad for your brain (see pages 28).1

This chapter encourages you to develop a more helpful and considerate response to yourself. Your sense of yourself is always with you, from the moment you wake up to the moment you go to bed. It makes sense to learn how to have a relationship that is friendly, supportive, healing and stimulates the positive emotion systems in our brain rather than the threat systems.

In depression, thoughts and feelings about oneself can become very negative. I say ‘can’ because this is not always the case. For example, I recall a woman who became depressed when the new people who moved in next door played loud music into the early hours. She tried to get the authorities to stop them, but although they were very sympathetic, they were not much help. Slowly she slipped into depression, feeling her whole life was being ruined and there was nothing she could do. However, she did not think her depression was her fault or that she was in any way inadequate, worthless, weak or bad. Her depression was focused on a loss of control over a very difficult situation.

Sometimes depression can be triggered by conflicts and splits in families or other important relationships. The depressed person may feel defeated and trapped by these relationships, but not to blame for them. Sometimes depressed people feel bad about being depressed and the effect this is having on them and others around them, but they do not feel that they are bad or inadequate as people; they blame the depression.

Nevertheless, many depressed people have a poor relationship with themselves. A poor relationship with oneself can pre-date a depression or develop with it. This chapter will explore the typical styles of ‘self-thinking and feeling’ depressed people engage in, and consider how our relationship with ourselves can be improved. All the styles discussed here can be seen as types of self-bullying. As you will see, we can bully ourselves in many different ways.1

We live in a world that is very judgemental and treats us rather like objects.2 At school, being chosen to play on the football team, getting our first job and so on, we are surrounded by people who can do better than us, who we feel are more attractive, more capable, and so on. What is worse – in schools, through our media and in workplaces, we are constantly encouraged to compare ourselves with others – are we as good as them; as clever, attractive or slim; or as wanted? My research has looked at how people can feel under pressure to strive to keep up and avoid being judged as inferior. You will not be surprised to learn that the more people feel under pressure to avoid being seen as inferior compared with others, the more vulnerable to stress, anxiety and depression they are.3

Social comparison can be helpful because it helps us copy each other – adopting the same values, wanting the same things and trying to improve ourselves. If we fail at an important task, such as an exam or the driving test, we can feel better if we find out that others have failed too. We might feel guilty at feeling pleased they failed too, but it’s only natural to feel better when you think you’re the same as others.

Depressed people can feel that others are more talented or lucky. As children they may have felt that parents favoured their siblings, or they may feel that their siblings had an easier time growing up.4 Sometimes depressed people have many un -resolved problems about these early relationships. They may feel that they have always lived in the shadow of a sibling – were less bright, less attractive and so forth. Sometimes parents and teachers have compared them unfavourably with others –‘Why can’t you be like Sam or Jane’ – or maybe they had parents who were always comparing them with others. For example, when Jane came second in class, her father’s reaction was always disappointment: ‘What’s the matter with coming first?’ His motto was, ‘Second is the first loser’. Such children grow up in an atmosphere of constant striving to compete with others to win parental approval; they never feel good enough. If you look back at pages 28–9 you can see how this can stimulate the drive system by trying to be ‘better and better or have more and more’ and never being satisfied or content. That is not your fault, but it is something you might wish to work on, to learn how to be more content and understand the roots of your striving and social comparison. Maybe it is searching for love and acceptance that underlies your striving?

Jim went to university and did well, but his brother Tom was a more practical person and not cut out for the academic life. However, instead of being happy with himself, Tom constantly compared himself with Jim and felt a failure. He would say, ‘Why couldn’t I have been the bright one?’

Babs’ mother was often ill, and as the older daughter she took on responsibility for caring for her. However, she didn’t feel appreciated for the role and grew up feeling secretly resentful, but always putting other people first and presenting herself as a nice person. Her anger at the situation, added to thoughts of how ‘compared with her’, her siblings had an easier life, fuelled her depression.

Even though social comparison can give us lots of problems, it’s interesting that sometimes we don’t compare ourselves with Mr or Ms Average or people who are similar to ourselves. Jane, a mother of two who devoted herself to looking after her children, had a number of friends who went out to work even though they had children too. Jane thought, ‘I’m not as competent as them because I don’t go out to work, and I have to struggle just to keep the home going’. When I asked her if she had other friends with children who did not have outside employment, she agreed that most of her friends didn’t. However, it was not them she compared herself with, but the few who did have jobs. Part of the reason for selecting people like this is that we slightly envy them; we want to be like them.

Sometimes when we compare ourselves unfavourably with others, we also think that other people will have the same judgement of us. Other people will see us as inferior or bad in some way – that we are not as good as other people (recall ‘Mind reading’ on page 207). This can be quite a major problem if we have to open our hearts and share our difficulties.

Diane felt really depressed after the birth of her child. She found it difficult to feel ‘affection’ for her new baby. She thought that her reaction was different from that of all her friends and therefore there was something wrong with her to feel this way. She was angry and frightened about her depressed feelings and envied what she saw as her friends being happy mothers. As a result, she never told anyone but suffered in silence, feeling different from them and cut off. Had she opened up to others (rather than feeling shamed by her comparisons) she would have found that these are sadly not uncommon experiences, and are no fault of her own – hormonal readjustment can be really unpleasant and play havoc with our minds.

One of the big benefits in working in group therapy is the degree to which people are prepared to share their problems. Often when one person is brave enough to own up to certain types of negative feelings or experiences, other people feel able to share. Indeed, sharing is much easier when we no longer compare ourselves unfavourably with others but realize we are all in this same boat of living in a world of suffering and hardship.

Social comparison is one reason why people who seem to have quite prestigious positions in society can become depressed. I worked with a doctor who had done well during his training yet, when he qualified, found the work stressful. He thought that he was doing much worse than his colleagues. Compared with them, he did not feel confident or on a par. As a caring GP he took more time with his patients and then struggled to keep up – but then blamed himself.

Although it can be very difficult to avoid making social comparisons, here are some ideas to think through to help you think about how social comparison works within you.

Self-blame and criticism are strongly linked to depression. When people self-blame and self-condemn, there is often a sense of the fear (e.g., of being rejected for mistakes or for not being good enough) and loss. Sometimes we learn to self-blame because we are frightened. Consider this on a world scale. Over thousands of years humans have been very frightened about what life can throw at them. Their children can die of numerous diseases, there can be famines and droughts and all kinds of unpleasant things. In societies throughout the world humans often imagine and then appeal to various gods who might be able to control bad things. Then they have to get them on side and they usually do this by sacrificing, appeasing or promising obedience to the chosen god. Problems arise if this does not work. The following year the diseases still come and so do the droughts, famines and other bad things. People rarely give up on their god as a poor bet; more commonly they blame themselves. They feel they must have done something wrong, or not done things sufficiently right, and have caused offence or displeasure to the god. Self-monitoring one’s behavior, to check if it is acceptable – and then self-blaming if one thinks it is not – are common if we grow in fear of others. Sometimes in these societies if the gods do not help out there is a blaming of other people, ‘Maybe it was those people who broke the traditions and caused the gods to abandon us’ – and so starts a round of persecution born out of fear.

When we believe that powerful others and people can help, love or hurt us – and when we’re children it is parents and teachers who can indeed do those things – it is natural for us to monitor ourselves, trying not to make them angry with us or to withdraw support and affection. Because we are monitoring ourselves, if things go wrong, we blame ourselves. If parents are in a bad mood, we might wonder what we have done to upset them. Thus a nat ural style of self-monitoring and self-blaming can become a style we carry through life. It is useful to remember that a style we learned out of fear – wanting to please and blaming ourselves, wanting to be loved or protected and not harmed – can become a style we use in all kinds of situations. We may never have learned to see the origins of our self-blaming style as being rooted in fear and wanting love.

If you tend to blame yourself, often worrying if you’ve upset people, not done well enough or have various faults – always try to think about what you are really frightened of. Next, write down the reasons why these might be linked to your fears (of rejection, or people becoming angry). You might not be fully conscious of them at first. Consider if these styles have been picked up in childhood. If so, with your compassionate self-focus, consider the possibility that you are blaming yourself not because you really are to blame, but because it feels safer to self-blame and to protect yourself – just like the people who blame themselves if their gods don’t come through for them. If it is about fear, safety and protection, then be honest about this, rather than thinking your self-blame reflects any truth about you!

Blaming occurs when we look for the reasons or causes of things – why did such and such a thing happen? When we are depressed, we often feel a great sense of responsibility for negative events and so blame ourselves. As noted above, the reasons for this are complex. Sometimes we self-blame because as children we were taught to. Whenever things went wrong in the family, we tended to get the blame. Even young children who are sexually abused can be told that they are to blame for it – which, of course, is absurd. Sadly, adults who are looking for someone to blame can simply pick on those least able to defend themselves.

Sylvia was a harsh self-blamer. Her mother had frequently blamed her for ‘making her life a constant misery’. Her mother was herself a depressed and angry person, but Sylvia accepted her mother’s explanations at face value – as children do. Not surprising, then, Sylvia took this style of thinking into adulthood and tended to blame herself whenever other people close to her had difficulties. Yet when Sylvia looked at the evidence, she realized that her mother’s life was unhappy for a number of reasons, including a difficult marriage and money worries. As a child Sylvia could not see this wider perspective, but believed what her mother told her. Sylvia had to learn that her self-blame was a style she had picked up in childhood, and practise a more balanced approach. Sometimes, of course, this is quite frightening because it raises a number of other issues about the kind of person she is and the anger she might now feel.

When people are depressed, their self-blaming can become extreme. When bad things happen or conflicts arise, they may see them as completely their fault. This is called personalization – the tendency to assume responsibility for things that are either not our fault or only partly so. However, most life events are a combination of various circumstances. When we are depressed, it is often helpful to stand back and think of as many reasons as possible about why something happened the way it did. We can learn to consider alternative explanations rather than just blame ourselves.

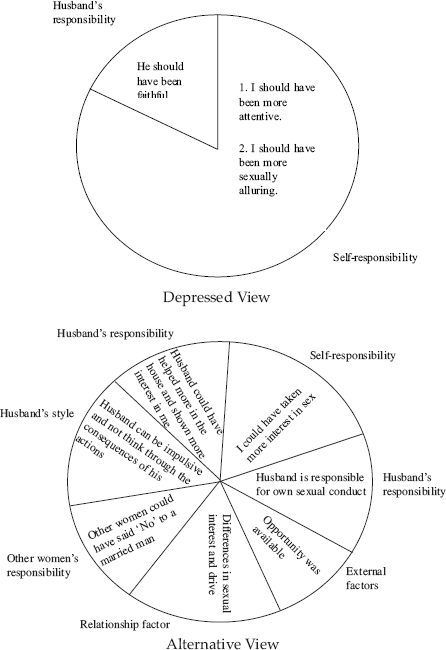

Many of the things that happen to us are due to many reasons. Here is an example to help you think about this. Sheila’s husband had an affair, for which she blamed herself. Her thinking was: ‘If I had been more attentive, he would not have had an affair. If I had been more sexually alluring, he would not have had an affair. If I had been more interesting as a person and less focused on the children, he would not have had an affair.’ All her thoughts were focused on herself. However, she could have had alternative thoughts. For example, she could have thought: ‘He could have taken more responsibility for the children, then I wouldn’t have felt so overloaded. He could have spent more time at home. If he had been more attentive in his lovemaking, I might have felt more sexually inclined. Even if he felt attracted to another woman, he did not have to act on it. The other woman could have realized he was married and not encouraged him.’

One can then write down these various alternatives side by side and rate them in terms of percentage of truth. Or one might draw a circle and for each reason allocate a slice of the circle. The size of each slice represents the percentage of truth. In Figure 13.1 you can see how this worked for Sheila. The two circles represent a depressed view and a more balanced view. Note how some situations often have many causes. Sheila’s more balanced, ‘alternative view’ circle seemed more true to her once she had considered it.

Figure 13.1 ‘ Responsibility circles’.

The next thing to do is to go around the circle carefully and think about it in as compassionate, warm, kind and understanding a way as you can. Try and create those feelings in your mind as you consider the alternatives.

Think about the fact that if we take too much responsibility on our own shoulders then we are robbing other people of theirs. In parent–child relationships this can be very important. If parents feel guilt and blame themselves for their children’s difficult or bad behavior, how are the children ever going to learn to take responsibility?

Tess had been depressed when her son Sam was born. Later on, she always blamed this for Sam’s difficult behavior. The family therapist spotted this and noted that Sam had few boundaries because Tess always blamed herself for his behavior. She could not confront Sam and help him become responsible for himself and his behavior.

Compassionate behavior is about giving people what they need, not necessarily what they want. When it comes to responsibility, don’t be greedy and claim more that your fair share!

The same principle can apply when we blame others. We may simply blame them without considering the complexity of the issue, and label them as bad, weak and so forth.

One reason we might self-blame is that, paradoxically, it might offer hope. For example, if a certain event is our fault, we have a chance of changing things in the future. We have (potential) control over it and so don’t have to face the possibility that, maybe, we actually don’t have much control. In depression, it is sometimes important to exert more control over our lives, but it is also important to know our limits and what we cannot control. Sheila had to face the fact that she could not control her husband’s sexual conduct. It was his responsibility, not hers. We have to be careful that, in self-blaming, we are not trying to give ourselves more control (and power) than we actually have (or had). We will look at this in regard to shame and abuse on pages 388–89.

Another reason for self-blame is that it may feel safer to blame ourselves than to blame others. By self-blaming we might avoid conflicts and expressing our own anger. You will need to be honest about this – how frightened of your anger are you? How much do you think it could turn you into an unlovable person? Remember the example above of the blaming ourselves if the gods don’t help out or seem punitive (see pages 281–2) – sometimes we can be very frightened of anger and conflicts, and it is out of fear that we self-blame.

It may be that self-blame keeps the peace and stops us from having to challenge others. If, when we were children, our parents told us that they hit us because we were bad in some way, we might have accepted their view and rarely argued. This attitude can be carried on into adulthood. The other person always seems blameless, beyond rebuke.

People can be in conflict and in dilemmas about blame. One part of the self can feel angry, but another part can feel sorry or disloyal to (say) a parent. There can be a real desire to avoid conflict, and not wanting to be seen as ungrateful, aggressive or bad. The problem is, of course, that conflicts are part of life.

Sometimes we recognize that we are not totally blameless in something, but when it comes to arguing our case, the part that is our responsibility gets blown up out of proportion. We become over-focused on it and feel that we have not got a leg to stand on. However, most things in life have many causes, and the idea here is to avoid all-or-nothing thinking. By all means, accept your share of responsibility – none of us is an angel – but don’t overdo it. Healing comes from forgiving yourself and others.

When bad things happen, depressed people sometimes feel that they are being punished for being bad in some way. It is as if we believe that good things will only happen if we are good and only bad things will happen if we are bad. If bad things happen, this must be because we have been bad, or simply are bad. When Kate lost a child to sudden infant death syndrome, she felt that God was punishing her for having had an abortion some years earlier. But millions of women have abortions and don’t suffer this event, and vast numbers who suffer this sad event have not had abortions.

In depression the sense of being punished can be quite strong, and quite often, if this is explored, it turns out to relate to a person’s own shame about something in the past. For instance, Richard’s parents had given him strong messages that masturbation was bad. When he began doing it when he was twelve, he enjoyed it but also felt terribly ashamed. For many years, he carried the belief that he was bad for enjoying masturbating and sooner or later he was going to be punished for it. When bad things happened to him, he would feel that these were ‘part of his punishment’.

To come to terms with these feelings we usually have to admit to the things we feel shame about and then learn how to forgive ourselves for them. It can be difficult to come to terms with the fact that the principles of ‘justice’ and ‘punishment’ are human creations. There is no justice in people starving to death from droughts in Africa. Good and bad things can happen to people whether they behave well or badly.

The fear of punishment can also come when we have had parents who frequently lost their temper and became very aggressive. Abigail’s mother could be loving but at times would have rages and be physically aggressive. Clearly, those events created intense fear in Abigail. It is quite understandable that if there were conflicts or things went wrong, Abigail’s threat-protection system would spring into action and she’d have an internal fear that something very bad or threatening was going to happen.

Expectations of punishment can operate at an emotional or gut level. It is important to stand back from that and realize what’s happening inside. We can then practise our soothing rhythm breathing (see pages 123–4), and recognize that our feelings make sense, but we can allow ourselves to be gentle with them now.

Note that Abigail had the classic problem of wanting love from a person who could also be dangerous. This is very tough, because different parts of her brain are in conflict. The part that wants to be close to a loving mother and yearns for protection pulls her forward while the threat self-protection system pushes her away. These are difficult and confusing feelings to have to deal with and can really scramble our minds. If Abigail gets close to people this might reactivate her fear that people she’s close to can blow up at her.

Some people can fear the punishment of Hell. But here’s how I see it. If you believe in Heaven then it’s kind and loving people who go there, right? And these are people who do not like others to suffer. So Heaven is full of those who would work to stop the suffering of others – so if Heaven if full of such souls, who could rest knowing people suffer in Hell – so how can Hell exist? For me it is our own minds that create these fears.

Some people believe that self-criticism is the only way to make them do things. For example, a person might say, ‘If I didn’t kick myself, I’d never do anything.’ Or they might believe that unless they are critical and keep themselves on their toes they will become arrogant, selfish and lazy. They use their self-bullying part to drive them on – sometimes in rather sadomasochistic ways. Such a person may believe that threats and punishments are the best ways to get things done. In some cases, this view goes back to childhood. Parents may have said things like, ‘If I didn’t always get on at you, you wouldn’t do anything’, or ‘Punishment is the only thing that works with you’. They may also have been poor at paying attention to good conduct and praising it, and rather more attentive to bad conduct and quick to punish. As a result, the child becomes good at self-criticism and self-punishment but poor at self-rewarding and valuing. See Table 13.1 for ways to look at this differently.

In depression, however, self-criticism can get out of hand. The internal bully/critic becomes so forceful that we can feel totally beaten down by it. Then, when we are disappointed about things or find out that our conduct has fallen short of our ideal in some way, we can become angry and frustrated and launch savage attacks on ourselves. Research has shown that it is the emotions of anger and contempt in the attacks, not just the kind of things you think or say to yourself, that really do the damage in self-attack.5

The late Albert Ellis pointed out that self-criticism can lead to an ‘it–me problem’: ‘I only accept me if I do it well.’ The ‘it’ can be anything you happen to judge as important. For example, if you are a student, the ‘it’ may be passing exams. You might feel good and content with yourself if you pass or do well, but become critical and unpleasant with yourself if you do less well. Your feeling of disappointment fuels negative feelings of yourself. Or the ‘it’ might be coping with housework or a job: ‘I only feel a good and worthwhile person if I do these things well.’ Success leads to self-acceptance, but failure leads to self-dislike and self-attacking. Not only may you feel like this, but you might have beliefs where you think it’s true: ‘I’m not worthwhile if I can’t succeed at things’.

This kind of thinking means: ‘I am only as good as my last performance’. But how much does success or failure actually change us? Do you really become good (as a person) if you succeed and become bad (as a person) if you fail? Whether we succeed or fail, we have not gained or lost any brain cells; we have not grown an extra arm; our hair, eyes and taste in music have not changed. The consciousness that is the essence of our being has not changed. It is like water that can carry good or bad things but the water itself is not those things. Of course, we may lose things that have importance to us if we fail. We may feel ter ribly disappointed or grieve for what is lost and what we can’t have. But the point is that these things will be more difficult to cope with if our disappointment becomes an attack on ourselves and we label ourselves rather than our actions as disappointing. It is very helpful to pull back and reflect on feelings of disappointment and consider if these feelings have somehow got linked to your feelings about yourself. If so, imagine your mind separating them and saying clearly ‘I am upset about this or that – but this is not about me or the essence of me’.

Another key way to work on this ‘it–me’ problem is to separate self-rating and judgements from behavior rating and judgements. It may be true that your behavior falls short of what you would like, but this does not change the complexity and essence of you as a person. We can be disappointed in our behavior (and we can all do some daft, thoughtless and unhelpful things), but as human beings, we do not have to rate ourselves in such all-or-nothing terms as ‘good’ or ‘bad’, ‘worthwhile’ or ‘worthless’. If we do that, we are giving away our humanity and turning ourselves into objects with a market value. We are saying, ‘I can be treated like a car, soap powder or some other thing. If I perform well, I deserve to be valued. If I don’t perform well, I am worthless junk.’ But we are not things or objects. We are living, feeling, highly complex conscious beings, and to judge ourselves as if we are just objects carries great risks.

Recent research has suggested it is our emotions and response to self-criticism that are associated with depression.5 Our research has also shown that people criticize themselves for different reasons. Sometimes it’s because they want to drive themselves to be better, but at other times it’s out of rage and hatred and just wanting to hurt themselves.6 We might make a mistake, have an argument with somebody, or eat too much and put on a few pounds, and realize that we could have behaved better. We might offer a mild rebuke to ourselves, or try to learn from things. However, when we attack ourselves there are emotions of frustration and anger and sometimes even contempt and shame. It is these feelings that we put into our self-criticism that turn it into much more of an attack on ourselves.

When self-criticism becomes hostile and activates basic beliefs about ourselves (of being weak, bad, inadequate, hopeless, and so on), then depression can take root. We all have a tendency to be self-critical, but when we become angry, frustrated and aggressive with ourselves and start bullying and labelling ourselves as worthless, bad or weak, we are more likely to slip deeper into depression. In a way, we become enemies to ourselves; we lose our capacity for inner compassion. It is as if the self becomes trapped in certain ways of feeling and then (because of emotional reasoning) over-identifies with these feelings. We think our feelings are true reflections of ourselves: ‘I feel stupid/worthless, therefore I am stupid/worthless.’

Here are some ideas about how to work with these difficulties:

Remember these thoughts and reflections have to pass the ‘compassionate friend’ test: Would you say this to a friend? Would you help a friend in this way? Would you agree that it is a kind and nurturing thing to think, say or do?

As I have mentioned, it is the fear-linked and hostile emotions lurking in the self-criticism that often do the damage. Getting more insight into these emotions and some control over them can be very helpful. At the extreme, some depressions involve not only self-criticism and self-attack, but also self-hatred.8 This is not just a sense of disappointment in the self; the self is actually treated like a hated enemy. Whereas self-criticism often comes from disappointment and a desire to do better, self-hatred is not focused on the need to do better. It is focused on a desire to destroy and abolish.

Sometimes along with self-hatred are feelings of self-disgust. Disgust is an interesting feeling and usually involves the desire to get rid of or expel the thing we are disgusted by. In self-hatred, part of us may judge ourselves to be disgusting, bad or evil. When we have these feelings, there may be a strong desire to attack ourselves in quite a savage way – not just because we are disappointed and feel let down, but because we have really come to hate parts of ourselves.

Kate could become overpowered by feelings of anxiety and worthlessness. When things did not work out right, or she got into conflicts with others, she’d feel intense rage. Even while she was having these feelings, she was also having thoughts and feelings of intense hatred towards herself. Her internal bully was really sadistic. She had thoughts like: ‘You’re a pathetic creature, a whining, useless piece of shit.’ Frequently the labels people use when they hate themselves are those that invite feelings of disgust (e.g., ‘shit’). Kate had been sexually abused, and at times she hated her genitals and wanted to ‘take a knife to them’. In extreme cases, self-hatred can lead to serious self-harming.

Kate’s difficulties came to light in therapy, and for these types of extreme problem, therapy may be essential, but they are helpful to think about on your own too, because it is important to try to work out, and see if your bullying, self-critical side has become more than critical and has turned to self-dislike or self-hatred. Even though you may be disappointed in yourself and the state you are in, can you still maintain a reasonably friendly relationship with your inner self?

If your internal bully is getting out of hand, you may want to try the following: In as warm and friendly a way as you can manage, say to yourself:

We need to consider, too, that we hate what hurts us or causes us pain. Rather than focusing on hatred, it is useful to focus on what the pain and hurt is about. If you discover that there are elements of self-hatred in your depression, don’t turn this insight into another attack.

The tough part in all this is that you will need to be absolutely honest with yourself and decide whether or not you want hatred to live in you. When you decide that you do not, you can train yourself to become its master rather than allowing it to master you. However, if you are secretly on the side of self-hatred and think it’s reasonable and acceptable to hate yourself, this will be very difficult to do, and it will be hard to open yourself to gentleness and healing. For some people, this is a most soul-searching journey. But as one patient told me:

The hard part was realizing that, whatever had happened in the past and whatever rage and hatred I carried from those years, the key turning point had to be my decision that I had had enough of my hatred. Only then could I start to take the steps to find the way out.

And, of course, it is not just with depression that coming to terms with and conquering hatred can be helpful. Many of our problems of living together in the world today could be helped if we worked on this. We all have the potential to hate – there is nothing abnormal about it. The primary question is, how much will we feed our hatred?

In this difficult and painful life, when we make mistakes, things don’t work out, or we do things we deeply regret, learning to be kind to ourselves is the most important lesson to help us with depression. The first thing is to decide if you are actually frightened of giving up the self-criticism and self-bullying. If you ask people to imagine what life would be like if they gave up self-criticism and self-bullying altogether, they can actually be quite puzzled and even frightened. They may believe they would not achieve anything; would become lazy, arrogant or unkind. It’s almost impossible for them to believe that they wouldn’t become lazy because they have a genuine wish to do well and a genuine wish to be kind.

The first thing is to make a distinction between what I call compassionate self-correction and shame-focused self-criticism or self-bullying. They are outlined and contrasted in Table 13.1. Compassionate self-correction is based on being open-hearted and honest about our mistakes with a genuine wish to improve and learn from them. No one wakes up in the morning and thinks to themselves, ‘Oh, I think I will make a real cock-up of things today, just for the hell of it’. Most of us would like to do well, most of us would like to avoid mistakes, most of us would like to avoid being out of control with our temper. We need to recognize that our genuine wish is to improve. Self-criticism, on the other hand, comes from a fear- and anger-based place. It is concerned with punishment and is usually backward-looking, related to things we have done in the past. The problem is you cannot change a single moment of the past, you can only change the future.

To appreciate the differences between compassionate self-correction and shame-based self-attacking, imagine a child who is learning a new skill but is struggling and making mistakes. A critical teacher will focus on those mistakes, point out what the child is doing wrong, appear slightly irritated, imply that the child is not concentrating or could do better if they try. The focus of that style of teaching is based on fear and shame – to make a child frightened or to feel bad if they don’t do well. In contrast, consider a kind teacher who focuses on what a child does well and shows them how they can improve and learn from mistakes, and genuinely takes pleasure in the child’s learning. Which technique do you think will help the child the most? Which one would you prefer?

If you do things wrong or make mistakes there is going to be regret, and momentary flashes of irritation, anger and perhaps calling yourself names. The point is though, how long do you stay here? How quickly can you switch to a compassionate refocusing?

The way we treat ourselves is quite complex, but the basic question is, can we be a friend to ourselves when things go wrong and we mess up? It is easy to criticize – critics are ten a penny. Compassionate self support is harder but well worth working for. One patient reflected on her depression and eventually recognized that her depression was strongly linked to her self-condemnation. ‘I condemned myself into depression,’ she said. ‘That was all that was in my head, but now there are compassionate alternatives and different feelings about myself.’

Dear inner critic,

I know that you get frustrated and upset and become angry with me. This is because you are frightened of what will happen if we don’t succeed/achieve/change etc. Actually, like me, you want to be respected, loved, cared for or admired – the basic human wants. The thing is, you worry that all these things will slip through your fingers unless we get our act together. Look, I understand your fear. I also understand that your response is to panic and lash out like this. I’m very sorry you feel so vulnerable. It’s not your fault but this attacking actually contributes to our feelings of vulnerability and depression, and so it’s time to learn how to be gentle and kind in these situations. We can learn to do the things that will genuinely move us forward in life. In your heart you know this. So I’m not going to attend to the things you say as much as I used to, okay? I used to get caught up in them and believe that these thoughts had some truth to them, but they don’t really – it’s just that we’re frightened of rejection. But if I am honest and compassionate I can learn how to cope with rejection if it comes.