Of all the emotions that are likely to reduce our ability to be helped, to reach out to others and to treat ourselves with kindness, shame is the most important and destructive. Indeed, people can feel ashamed about being depressed, and desperately try to hide it from others. If we can recognize our inner shame and work to reduce it, we will do much to heal and nurture ourselves.

In general, shame – like embarrassment, pride, prestige and status – is related to how we think others see and judge us, and how we view ourselves. We call these self-conscious emotions because they relate to our feelings about ourselves.1 The word ‘shame’ is thought to come from the Indo-European word skam, meaning to hide. In the biblical account, Adam and Eve ate of the apple of the tree of knowledge, became self-aware and realized their nakedness. At that moment, they developed a capacity for shame and the need for fig leaves – or so the story goes. Part of their shame was fear that, having transgressed against God’s instructions, they would be punished.

Shame is now regarded as one of the most powerful and potentially tricky issues in helping people with depression, because it often involves concealment or an inability to process ‘shameful’ information. People don’t easily reveal or talk about things they feel ashamed about – they’re worried about what others will think of them. Indeed, some people are ashamed of depression itself and this is why, sadly, they don’t seek help.

Shame is a complex phenomenon, with various aspects and components. Among the most important ones are the following:

The most powerful experiences of inner shame often arise from feeling that there is something different and inferior, flawed or bad about ourselves. We may believe that, if others discover these flaws in us, they will ridicule, scorn, be angry and/or reject us. In this respect, shame is fear of a loss of approval in extreme form.

We can feel paralysed by shame and at the same time acutely aware of being scrutinized and judged by others. Shame not only leads us to feel inferior, weak or bad in some way, but also threatens us with the loss of valued relationships – if our shame is revealed, people won’t want to help us, be our friends, love or respect us. A typical shame-based view is, ‘If you really got to know me, you would not like me’. A major feeling in shame can be aloneness. We can feel isolated, disconnected and inwardly cut off from the love or friendship of others. Shame can give us the feeling that we are separated (different) from others, an outsider.

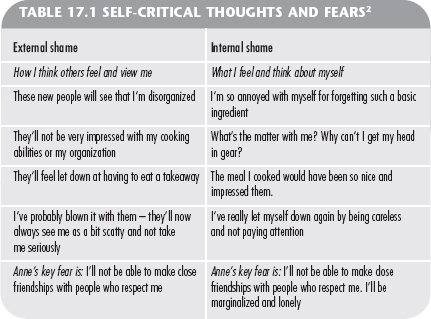

It is helpful to distinguish in our minds internal shame (how we judge and feel about ourselves) from external shame (the feelings we have about ourselves when we think others are looking down on us). Let’s look at this distinction with an example. Recall Anne from Chapter 9 (pages 190–3) who burnt her party dinner. She may be very concerned about what other people think, and worry that they may see her as incompetent and inadequate in some way. Her attention is focused on what is going on in the minds of other people and her social standing in their minds. This is external shame because the source of the criticism and the attention is outside (external) of herself. If she is self-critical and harsh on herself, maybe calls herself names and feels irritated with herself, then she will also have internal shame. The source of the criticism and put-down is coming from within our own minds. Table 17.1 outlines these distinctions and shows how they are linked to our key fears.

However, it is possible that Anne could be upset because she believes others look down on her but is not self-critical and accepts she’s not a particularly good cook. Anne might have external shame but no internal shame. If Anne is convinced by the genuineness, if people reassure her, that they don’t mind the meal being overcooked, she will quickly calm down, because she trusts others to still like and care about her. The kindness of others is soothing. Internal shame, however, is less easily dealt with because it’s our own internal judgements, evaluations and feelings – and these we can find more difficult to settle. This is why it is important to learn self-kindness. Look back to pages 190–3 and note some of the suggestions for working on this problem.

In depression it is common for people to have both types of shame. They feel others see them as inferior, bad or inadequate; and they also see themselves as inferior, bad or inadequate. When you are working with your own sense of shame, then, it is useful to be clear about:

When you do this, you will see how often shame feelings are related to fears of loss of approval. In this chapter we will focus mainly on internal shame; that is, the kind of things you say to yourself that trigger feelings of shame in you, make you behave submissively and undermine your confidence.

Shame can affect us in many ways and we can defend against it in many ways. The first thing to recognize is that we feel insecure in the minds of others in some way. We’re not sure whether they accept us or not. If we grow up knowing that others are accepting, validating and forgiving, we tend to be less bothered by shame than if we grow up in neglectful, harsh, rejecting or critical environments. If shame is a major problem for us, learning how to deal with it compassionately can help.

According to the psychologist Gershen Kaufman,3 there are at least three areas in which shame can cause us much pain. We can feel shame about our bodies, shame about our competence and abilities, and shame in our relationships. There is an additional aspect that is especially common in depression: shame of what we feel, or the things that go through our minds. Let’s briefly look at each of these.

Some people don’t go to see their doctors because of shame. There are all kinds of conditions that people regard as shaming: piles (haemorrhoids), impotence, bowel diseases, urinary problems, eating disorders, drink and drug problems. Shame, perhaps more than any other emotion, stops us from seeking help. There is general agreement that doctors could be more sensitive to shame, how to spot it and work with it.

Sadly, too, people who have various disfigurements – from mild acne to severe burns – can also feel shame, especially if others laugh at them, reject them or appear repelled by the way they look. But people cope with these in different ways (see www.changingfaces.org.uk/Home).

People who have been sexually abused often have an acute sense of bodily shame. They can feel that their bodies have become dirty, contaminated and damaged. In extreme cases, these individuals may come to hate and even abuse their own bodies. Talking about the experiences and feelings of abuse can in itself produce strong feelings of shame, and for this reason people may hold back from discussing them. Healing this shame involves coming to terms with one’s body and reclaiming it as one’s own (see below).

Concern with the way we look is, of course, a driving force behind fashion. However, some people feel so awkward and ashamed of their bodies that they will do almost anything to themselves to avoid suffering these feelings. People might spend hours body-building at a gym, and put great effort into dieting to make themselves thinner. Make-up and plastic surgery may also be used to avoid feelings of body shame. In the West today much depression emerges out of feelings of shame and unhappiness with the shape and size of our bodies – hence the huge dieting industry, which offers hope of change. Sometimes we can over-hope, in the sense that we might believe something like, ‘If I lose weight then people will like me more and I will be happy’. If we try and fail, as people often do (I can’t tell you how often I have tried to lose weight) then again that can feel shaming.

Georgie struggled to lose weight. She lost a couple of pounds then put them back on again. This caused a dip in mood and she was very down on herself and then ate more.

The issue about helping ourselves if we are overweight (and that includes me – unfortunately) is learning how not to shame ourselves if we don’t do as well as we would like. We learn to be kind and understanding of our setbacks, while also trying to encourage ourselves to try again. If we are shaming of ourselves, we are much more likely to give up. Sometimes we need to simply learn to come to terms with the size we are and develop self-acceptance. At times, a bit of ‘What the hell’ in our lives can be helpful! (See page 501.) Think about joining a slimming organization because here you might receive help, guidance and a lot of understanding and support from other members. Talking to others helps us to see that we are all struggling with the same things – it not just ourselves – so we don’t need to cover up or hide away.

This kind of shame relates to performing physically or mentally. For example Pete would become very angry with himself when he was unable to make things work. When household appliances broke down, he took it as a personal criticism of his abilities and manhood if he could not fix them. When his car wouldn’t start, he would think that, if he were a proper man, he would be able to understand mechanical things and would be able to fix it. He hated taking it to the garage and showing his incompetence to the garage staff, and so always asked his wife to take it.

In my own case, my poor English has often been a source of mild shame. My teachers at boarding school would write in my report that I was lazy and careless. I could spend hours on a piece of work, reading over and over it, and feel confident it was ‘spelted’ correctly, only for it come back covered in red marks with comments like, ‘Slapdash, Gilbert!’ – which then triggered that dreadful heart-sink feeling. Dyslexic children often experience much shame and feelings of being defective and inferior. The main point here is that attempting to do things and failing can be a source of shame. It is made worse when we rate ourselves as bad, and attack ourselves for failing. As a rule, it is easier to cope with the criticism of others if we don’t attack ourselves. If we do, then there are attacks from the inside and outside and that can feel a very unpleasant place to be in! The next time you feel embarrassed at a failure, check to see if you are self-attacking and bring your rational/compassionate mind into play. My own experiences made me very aware of the power and pain of shame and why kindness and compassion are such helpful antidotes. I am also very grateful to copy-editors!

None of us like criticisms – although who is doing it and how it is done is important. However, when our shame sensitivities are touched we can become alarmed, anxious, defensive, angry, sulk or give in quickly. This can give us difficulty owning up to our vulnerabilities, for fear that, if others became aware of them, we would be marked down as weak and inadequate. Fear and shame of criticism can make relationships difficult because we find it hard to ride the ups and downs of relationships.

Some people feel awkward when wanting to express or respond to affection in the forms of gentleness, touching and hugging. It is as if there is an invisible wall around them. In situations of close intimacy, their bodies stiffen or they back away. Some may hide their shame by clinging to the idea that, ‘Grown men don’t do that sort of thing’ or that to be tender is to be ‘soft’ and ‘unmanly’. This can cause problems in how they act, as intimate friends, lovers and fathers. For example, children often seek out physical affection, and it can be very hurtful to them if their fathers push them away when they try to get close.

We sometimes conceal our true feelings out of shame. We can be ashamed of feeling anxious, tearful or depressed or angry – as if the very fact that we have these feelings means that there is something wrong, flawed or unlovable in us. People with shame about their feelings can’t believe that others have the kinds of feelings or fantasies they do.

For many years, Alec suffered from panic attacks. He dreaded going to meetings in case the signs of his anxiety showed. He was so ashamed of his anxiety that he did not even tell his wife. Eventually he broke down, became depressed and could not go to work. Then the story of his long suffering came out. From a young age, his father had told him that real men don’t get anxious; they are tough and fearless. When Alec had been anxious about going to school, his father had been dismissive and forced him to go – shaming him in the process. By the time he was a teenager, Alec had learned never to speak of or show his inner anxieties.

Susan, who was married, met another man to whom she felt strongly sexually attracted. She flirted with him and would have liked the relationship to become sexual, but she felt deeply ashamed about her desires and believed that they made her a very bad person. As she came to understand that sexual feelings are natural, and to explore what it was about the relationship that so attracted her, she discovered a desire for closeness that she could not get from her husband. This, of course, raised the question of what she could do about that; but it helped stop her being ashamed of her feelings and allowed her to accept that she, like other human beings, wanted closeness and could find a whole range of people rather sexy.

Jenny’s mother had told her that sex is dirty – something that men enjoy because they are more primitive and superficial than women. Later, when Jenny had sex, she could sometimes push these thoughts aside, but afterwards she was left with the feeling of being dirty and of having betrayed her mother’s values. When she monitored her thoughts during the day, she noticed that, whenever she had sexual thoughts and feelings, she would also have thoughts at the back of her mind of ‘A good woman doesn’t have these feelings. Therefore I’m dirty, and if my mother knew what was going through my mind, she would be disgusted and disappointed with me.’ She then distracted herself from her sexual feelings and turned them off.

These were not clear thoughts as I have written them down – they were more sensed, and Jenny had to stop and really focus on ‘what am I actually thinking here?’ to get a handle on them. However, once she had come to recognize that she was having these kinds of thoughts (and she had to really focus to ‘catch’ them going through her mind), she was able to say to herself:

This is my sexual life and it does not belong to my mother for her to control. If I feel sexual, this is because I feel sexual, and it has nothing to do with being dirty. My sexual feelings also give me energy and are life-enhancing. I don’t need to act out my mother’s sexual hang-ups in my own life.

Andrew was ashamed of his homosexual desires. Brought up within a strict religious framework, he thought that these feelings were a sin against God and that he was a bad, worthless human being for having them. Although it was a struggle, he began to explore the possibility that there were alternative ways to think about and explore his sexuality – without being ashamed of it.

Gary was ashamed of his anger and rage. When he became angry, he felt terrible and unlovable. He said that he just wanted to act like a decent human being, and, more than anything, he felt that his anger made him a horrible person. Indeed, his self-criticism often told him that he was horrible, ungrateful, selfish and self-centred. As a result, he could not explore all the things that hurt him and the reasons behind his anger. Instead, he simply tried to keep a lid on his anger rather than acknowledge its source, go in to accept it and work out how to heal it. The dip in mood for feeling (or at times expressing) anger is more common in depression than is sometimes recognized. Indeed, Freud thought anger was central to depression.

At times, Patricia felt very tearful, but she would not allow herself to cry – she was too ashamed. Leo hid the extent of his drinking out of shame. Zoe was too ashamed to talk about the fact that her husband was abusing her. Amanda could not go far from her house just in case, when she needed to use the bathroom, there was none available and she would wet herself. There are many, many examples. For a moment let us feel compassion for all those who suffer with shame.

We often use the expression – ‘it’s a crying shame’ – to denote perhaps that shame can involve tearful feelings and wanting to be loved. Let’s look at crying and shame, because some depressed people really struggle with this. They see crying as a sign of weakness or of falling apart and are ashamed. Table 17.3 shows some shaming thoughts and balanced/compassionate alternatives.

Sometimes people don’t realize (or have not had a chance to learn) that feelings can be complex; one can have different and conflicting feelings towards the same thing or person. Some people believe you should never be angry or want to leave a person you also love; that they should never annoy you to the point you want to shout at them, but that is the way of life.

If we have learned to hide our feelings in early life, then professional help may be useful to help us start to explore them more. But remember we all have feelings and some of them can seem very powerful – indeed overpowering or explosive. If you feel like that then that is not your fault (it’s to do with the way our brains are, and depression states) and once you give up self-blame you are freed up to seek out ways to help yourself.

Ever been in a high building or on the edge of a cliff? It is quite common for people to experience a feeling of being drawn towards the edge of high buildings with the thought of jumping off. This can be a bit frightening and we may wonder why we would have such frightening thoughts. But the fact is, given this tricky brain of ours, we can sometimes have thoughts that are in direct contrast to our true wishes. These thoughts and fantasies are called contrast thoughts. For people who have obsessional disorders, where such thoughts and images are common – they are called obsessional contrast thinking – thinking in complete contrast to one’s actual wishes. Another example is that we might have a violent thought about someone we love. Having sexual thoughts or desires that seem odd or outside the norm can also be frightening. Contrast thoughts can intrude into our minds, can be distressing but are common.

If people feel ashamed of their contrast thoughts they may try to hide them or not think about them (which normally makes them worse), or ruminate on why they had them. Sometimes they can worry about acting out their thoughts, and this can link to a condition called obsessive compulsive disorder. Some people think that having a thought is as bad as an action. To address the shame aspect, you might consider that writers of horror stories write down their bizarre (and at times very violent) fantasies and thoughts and can make a lot of money out of them – whereas depressed people can be frightened of theirs. The writers know how bizarre our minds can be, while some depressed people think we should always be rational and reasonable. The fact is we have difficult minds to work with, and our minds can be filled with all kinds of odd ideas and fantasies – through no fault of our own! Learning how to notice them, accept them and let them pass, seen as products of our odd, evolved brains, can sometimes help. If they are more persistent you may find it helpful to talk with your family doctor.

There are a number of theories about the origins of shame. According to one view, evolution has equipped children to enter the world as social beings with an enormous need for relationships, care, joyfully shared interactions and recognition. The treatment we receive at the hands of those who look after us will have a major effect on whether we move forward with confidence (the result of the many positive experiences encountered while growing up) or with a sense of shame, of being flawed, not good enough, lacking value or worth. Research has shown that the way the caregiver and infant interact has important impacts on the infant’s nervous system, emotions and sense of self.

Shame can arise from at least three different types of reactions to the treatment we received from our parents or others who have cared for us in our early lives:

Consider the following scenario. Three-year-old Tracy sits quietly, drawing. Suddenly she jumps up, rushes to her mother and proudly holds up her drawing. The mother responds by kneeling down and saying, ‘Wow – that’s wonderful! Did you do that?’ Tracy nods proudly. ‘What a clever girl!’ In this encounter, Tracy gets positive attention, and not only experiences her mother as proud of her, she also has emotions in herself about herself – she feels good about herself.

However, suppose that, when Tracy went to her mother with her drawing, her mother responded with, ‘Oh God, not another of those drawings. Look, I’m busy right now. Can’t you go off and play?’ Clearly, this time the way that Tracy experienced her mother, the interaction between them, and the feelings in her -self about herself were quite different. Tracy would be unlikely to have had good feelings in herself, and may have had a sense of disappointment and probably shame. Her head would have gone down and she would have slipped away. Thus a lack of recognition and a dismissal of ourselves, when we display something attractive to others, can be shaming. Experiences like this happen in even the most loving of homes and children learn to cope with them; but if they are common and arise against a background of insecurity and low parental warmth, they can, over time, be quite damaging.

One of my patients who read this section said that it brought back memories of herself as a child, when she would be sent to her room to play and ‘just keep out of the way’. Throughout her life, she had never felt wanted and had developed a sense of being in the way and a nuisance (see pages 313–16).

Donna’s parents were very ambitious. They wanted the best for her, and wanted her to do her best. If she came second or third in class, they would immediately ask who came first and indicate that coming second or third was okay but not really good enough; with a bit more effort, she could come top. Donna came to believe that nothing other than coming top was good enough to win the approval from her parents that she so desired. Anything less always felt like a disappointment for them and herself. You can guess what this all led to – an underlying belief and emotional sensitivity that, unless she did everything perfectly, she was flawed and had let herself and others down. Donna was rarely able to focus on what she had achieved, but thought only about how far short she had fallen.

Indeed, throughout life we seek the approval of other people, especially those close to us. If friends come to dinner we want them to tell us they’ve had a lovely meal – not that our meal was okay – average, they’ve had better and worse. We meet a new lover; we want them to say that our lovemaking was great – not that it’s average – they have had better and worse. The desires to create positive feelings in the minds of others is all very human – and we can feel a sense of shame if we struggle to do this.

We all have a very strong desire to conform and be accepted. We want to feel that we belong somewhere. We follow fashion and express the same values as others so that we can signal that we are one of the group. We follow gender stereotypes. We are highly motivated to try to be valued by others rather than devalued. All around us are values and standards to which we are supposed to conform if we don’t want to be shamed and stigmatized. The awful Chinese practice of foot binding, and other such practices of mutilation, can be kept in place via cultural shame to conform.

We may even try to avoid shame by going along with others, showing that we are made of the ‘right stuff’, even if, in our heart, we know that our action is immoral. Keith told me that getting into fights was often more to do with avoiding the shame of not fighting than with any real enjoyment in, or desire for, a punch-up; yet no one in his group wanted to ‘break ranks’ and point this out. Conforming to cultural values to avoid shame is a powerful social constraint. To risk exposure to shame is to risk rejection and not belonging. The pressure to conform can lie behind our cruelty to ourselves and others.

We also know, of course, that children and adults can be shamed directly by being told that they are stupid or bad, that they don’t fit in or are unwanted, and by being physically attacked. Indeed, some people will deliberately use the threat of shame, and the human built-in aversion to it, to control others. Shame does not only arise because approval and admiration are withheld; direct verbal and physical attacks can shame, too.

Let’s look at this in more detail, because it will reveal something of the power of emotional memories. Imagine a child called Joe who has annoyed a parent. The parent shouts at Joe and tells him he is a stupid boy. Joe will have the following experiences: a triggering event and then awareness of the arousal of anger in the mind of the other (in this case the parent). That anger will be picked up by Joe’s brain as threatening and dangerous, which will activate anxiety – even panic. Without thinking, Joe’s brain will automatically be trying to work out the best defensive responses, such as anxiety, wanting to run away, head-down submissiveness and/or freezing. Note also that in that moment no one comes to help Joe; he is alone in this very threatening situation.

A host of different emotions and urges to do things (such as run away and hide) are being welded together. There is the awareness of anger in the other; there is the awareness that somehow his own behavior may have caused this threat from the parent to arise; there is intense anxiety arising in himself; there is a sense of aloneness and being isolated; there is an awareness that no one will rescue him; and of course there are the verbal labels of being ‘stupid’. All these come together in that experience to form the core of an emotional memory. Like any powerful emotional experience and memory, it will influence our thoughts and feelings about ourselves and others, and our behaviors. The key point is to think about what Joe is learning about himself and others here. How easy will it be for Joe not to develop beliefs that he is stupid and that this ‘stupidity’ could get him into trouble? Not easy.

If the parent apologizes and explains their behavior, and at other times shows affection and praise, Joe can put this down to parental anger and not to himself, or that he is basically okay but needs to be careful at times. Problems arise if this does not happen, and Joe’s most intense emotional experience of his parent is of anger and being labelled. Now in the future, criticism and anger in others could activate those emotional memories and feelings in Joe, including anxiety and a sense of aloneness. These feelings might flush rapidly through his body if someone is critical of him.

The point is, we can see how shame experiences can lay down powerful and complex emotional memories which can be triggered again in the future. Sometimes when we experience shame, and those heart-sink feelings, it is useful to think about the kinds of early experiences that might have made us vulnerable and then to practise compassion for those memories (see the exercises at the end of this chapter).

Sexual abuse has been found to be linked to chronic depression. In many cases where this is so, the people who were abused will often feel intense shame and be self-blaming and accusing – even though they were children or young adolescents at the time.4

The reasons for this are complex but can be a sort of self-protection because blaming the abuser can feel dangerous or confusing in some way. Clearly abuse can’t possibly be a child’s fault, because, as David Finkelhor pointed out some years ago, before anything happens, before the child is even involved, things are going on in the mind of the abuser. For example, there is the ‘desire’ in the abuser, and willingness to take advantage of a smaller person who will be in a relatively powerless position. The abuser has to overcome any moral scruples, and in today’s society clear messages of wrongdoing. They need to manipulate the child into a position where they get them alone and can engage in the act, and they may overcome the child’s resistance either with fear or some placating tactic: ‘It’s okay, this is a loving act really’.

In this book on depression we can’t explore in too much detail how to tackle feelings of this kind of shame and self-blame. There are a number of books that specifically address this painful area.5 There are also phone and Internet helplines, some of which are listed in Appendix 3. What we can say is that, using a compassionate approach, there are a few things that might be helpful to consider. First, as noted above, abuse begins in the mind of the abuser. Second, if you think about the size and power discrepancies between the child and an adult or older person, it’s clear where the power is. Third, we need to address the issue of shame, because sometimes people feel that only if they can convince themselves they were not to blame can they not feel ashamed. Books that put a lot of emphasis on why you are not to blame can sometimes imply that that’s the only way to heal oneself of shame.

But in fact there is actually nothing to be ashamed about in sexual abuse. It may be tragic, terrifying, betraying, confusing, sad or ‘just was’. Those are some of the ways people will describe how they experienced it. As Carolyn Ainscough and Kay Toon note in their book, there are different experiences.5 Some children are traumatized and terrified by aggressive threatening abusers. Others are seduced into going along with things that they’re unsure about, or they might find their bodies behaving in what appear to be aroused ways. Keep in mind that sometimes we find our bodies acting aroused – because that’s what bodies do. If I’m absorbed in a scary movie, even though I know perfectly well it is only a film I can’t necessarily stop my body from being anxious. Bodily feelings don’t obey any logic. And of course sometimes children can confuse affection in these interactions and go along with things – so it is not your fault.

There’s a more important point still, far beyond blaming. This is that there is nothing to be ashamed of in being abused. It is sadly common throughout the world and has been for many thousands of years. It is a tragedy, something that might have been very frightening, a betrayal, a confusion, and a grief, but once you decide not to be shamed by it, you can become compassionate to your experiences and kind to your suffering.

Sometimes we won’t let go of shame and self-blaming because it’s a way for us to feel in control. If we really understand that it was not our fault and we had no control, this can be very frightening. Sometimes people say self-blame is the only way to make sense of it. I am all for making sense of things if they are genuine but there is no point in making up explanations – and when you would not make those blaming judgements if you were thinking about another child in your position. Our lack of control is the reality and the question is how we are able to be honest, humble and acknowledge some of our limitations in this life. This is not easy, so do reach out for help.

Another problem is that our efforts to shame perpetrators can cast a shame shadow over the survivors. As one abused person said, ‘Society regards sexual abuse as disgusting, therefore if people knew my past they would see me as disgusting.’ Indeed it is not uncommon for people to feel ashamed because they are worried about how other people will see them if they discover their past.

Because of this, people can feel ruined or damaged; anger they might feel towards the abuser can be directed at themselves because of the sense of being scarred. They don’t like themselves because they feel that other people wouldn’t like them if they knew. However, it can help to open our hearts to the fact that hundreds of thousands of children in the world are abused, and have been throughout history. Indeed, in some places in the world today, marriage between young girls and older men is still allowed. Sexual desire towards children or family members creates tragedies and traumas but, I would suggest to you, not shame, and in your compassionate, wise mind I suspect you know this already – if you tune into it.

Let me show this to you. Consider that if you knew of a child or young person going through these experiences, would you want to point the finger, call them names and shame them? I doubt it. It is far more likely that you would want to reach out to them with gentle support, kindness and rescue. For those children who are suffering today we wish for them to be free of their suffering, not for them to be ashamed.

If you are struggling with these experiences, and you believe that they may well be part of your depression, then open your heart to recognizing you are one of many; there is nothing shameful in what happened to you. Remember abuse has been part of the human condition for thousands of years. Note too there are many trained people out there who are skilled and keen to offer compassionate help. Most reputable support helplines are completely confidential. You can ask about your situation and see if you feel safe enough to realize that, whatever the circumstances of your abuse, good therapists will never shame you but will help you work through it so that you can gently heal and value yourself. The key thoughts are openness and honesty, kindness and understanding for yourself. Compassionately work on any self-blaming or self-dislike, and reach out for help – your family doctor may also be able to help you with this.

As we enter depression, we can get caught up in various circles of negative thinking and behavior, and shame can lead to several forms of self-perpetuating difficulties. At times, these can give rise to what I call a shaming loop (see Figure 17.1). This is particularly true of teenagers, adolescence being a time when the approval of peers and the potential for shame can have particularly significant effects. Many children are prone to being teased; some, sadly, more so than others. Coming to terms with teasing can be important for adolescents, and there are positive ways to do so, such as finding other friends or learning to ignore the teasing. Some individuals, however, turn to all kinds of things to ensure that they are not rejected in this way. Simon, for example, told me that he stole from local shops to give things to ‘friends’ so that he would be accepted and win some status or prestige from them. Sadly, through much of his adult life he had felt that he had to give ‘tokens’ to others before they would accept him.

It is not always the case that feeling inferior leads to social withdrawal – but it can do, especially when people label and attack themselves. When feelings of inferiority do lead to social withdrawal, then such individuals are also more likely to be rejected because they signal their feelings of inferiority to others. Unfortunately, adolescents in particular, but also adults, do not find withdrawn behavior attractive. The very thing that these people were hoping to avoid – being seen as inferior and being rejected – can happen because of the way they behave.

Figure 17.1 The ‘shaming loop’.

If shame is so powerful, how do we cope with it? One way is to avoid it, by avoiding being seen as inferior, weak or vulnerable. You never put yourself into a situation where you could feel it. While the methods below may work for a while, problems can arise if they are adopted over the long term.

This involves efforts to prove to yourself that you are good and able, and to avoid at all costs being placed in an inferior pos -ition. Sometimes we engage in vigorous competition with others to prove our own worth to them and to ourselves. It is as if we are constantly in a struggle to make up for something or prove something. Of course, we are trying to prove that we are not in -ferior, bad or inadequate and thus can be accepted rather than rejected. A therapist colleague told me (kindly) that this is why I write so much – but then, hey, we are all neurotic and it is how we use our neuroses that’s important. I like writing now because I have copy-editors who can save me from shame!

This occurs when individuals hide or avoid that which is potentially shameful. Body shame (including shame of decay and disease) may lead to various forms of body concealment. In the case of shameful feelings, we may hide what we feel. Other people are always seen as potential shamers who should not be allowed to peer too closely at our bodies or into our minds. When we deal with shame in this way, much of our lives can be taken up with hiding – even hiding things from ourselves. We can repress memories because they are too painful and shameful to know and feel.

Laughter may be used to distract from shame. We may make jokes when we feel mild shame, to divert others’ attention from it. When it is used to stop us from taking ourselves too seriously, joking can be very useful; but laughter employed to avoid shame often feels very hollow underneath. Some comedians use shaming humour which can actually be a cover for their own fragilities or anger.

Concealment can sometimes produce another form of shaming loop. For example, Janine would become defensive and irritated if the members of her therapy group began to talk about issues that touched her shame. This made the other group members irritated in return. They felt she was not being honest or facing up to her problems. This actually caused Janine to feel even more shame, and so she closed down even further. Thus her way of trying to hide her shame actually produced more shaming responses from others.

As I noted above, anger and blaming others can be a response to external shame: ‘If you shame me, I’ll hit/hurt you.’ This is retaliatory shaming. Violence, especially between men, often arises as a shame avoidance strategy – a form of face-saving. In some male gangs it is the most important and powerful source of violence. Shame violence and feelings of humiliation can be acted out in many ways.

Ray had been caught stealing at school. When his father found out, he gave him a ‘good thrashing’. What happened here is that Ray’s father felt shamed by his son’s conduct, believing that his son had disgraced him and the family. Not able to recognize or deal with his own shame, the father had simply acted out his rage on his son. This, of course, compounded Ray’s shame and anger. Had Ray’s father not felt so ashamed of his son, but instead been concerned to help him, he might have been able to sit down and explore what this stealing was about.

Natalie and Jon had a disagreement in public, and Natalie contradicted Jon. When they got home, he threatened her, saying in a very menacing way, ‘Never show me up in public again, or else!’

Usually, shame and counter-shaming interactions do not reach the stage of violence. Nonetheless, they can involve a good deal of blame and counter-blame. Each person attempts to avoid being placed in the bad or wrong position. You might recall the interaction between Lynne and her husband Rob from the last chapter (see page 360).

Projection is used in two ways. The first is mind reading, where you may simply project your own opinions of yourself on to others. If you think that your performance is not very good and label yourself as a failure, you believe that others will think the same. You assume that you are not very lovable, so you take it as read that others will think so, too. You feel that crying is a sign of weakness, so you think everyone else does, too.

A more defensive kind of projection involves things about yourself that you are fearful of or have come to dislike. You hide these from yourself, but see them in others. It is the other person who is seen as the weak, shameful one – not you. Condemning homosexual desire, for example, may be a way of avoiding acknowledging such feelings in oneself (which are feared), seeing them only in others who may then be attacked. Sometimes bullies hate the feelings of vulnerability in themselves and so they attack others in whom they see these feelings. Some bullies label others in the same way that they would label themselves if they could ever reveal their own vulnerability or hurt. Such people project those aspects that they see as inferior in themselves. Racist and sexist jokes can be a result of this.

If people criticize or attack you, it is possible that they see something in you that they don’t like in themselves. For example, Sandra sometimes cried about feeling alone. Her husband Jeff would become quite angry at this, which Sandra took as a criticism of her crying. But it turned out that, as a child, Jeff had himself been criticized for crying. Not only did he view Sandra’s crying as a criticism of himself (he thought it meant she was not happy living with him), but he also hated the feelings of vulnerability that might lead to him crying. Thus, Sandra’s crying reminded him of things he was ashamed of in himself.

So, if people put you down or try to shame you about something (perhaps for crying or failing or needing affection), ask yourself: How do they cope with these things? How do they cope with crying or failing? If you reflect on this and recognize that they don’t allow themselves to cry, or that they become quite angry when they fail, or that they have problems with affection, then it is wise to consider that perhaps they are criticizing you because they can’t cope with these things themselves. Whatever you do, don’t get caught up in the idea that they are right and you are wrong.

We touched on humiliation a little above in the section on violence. Humiliation is similar to and different from shame. Both involve painful feelings, of being put down, harmed or rejected. We believe that the other person (parent, partner, boss) is sending signals that we are unacceptable, inadequate or bad in some way. This is external shame, but in humiliation we focus on the ‘badness’ in the other, not in ourselves.

Feelings of humiliation, where we feel unfairly criticized or injured, can ignite powerful desires for revenge. Indeed, you can tell the extent to which you feel humiliated by the intensity of your thoughts about the injustice done to you and the strength of your desire for revenge. For some people, their fantasies of revenge are frightening and so they are hidden away. In such cases, acknowledgement of anger is a first step. For others, the anger and desire for revenge are constantly present, and they need to discover ways to work through the humiliation and let it go.

You may be vulnerable to feelings of humiliation now because of things that happened to you in the past. However, sitting on a lot of desires for revenge is not helpful to you. This is not to deny that very harmful things may have been done to you; rather, it is to say that if these feelings are not worked through, they can lead to a lot of mistrust of others and a tendency to constantly want to get your own back. This is a very lonely position and will keep your threat system stimulated by your vengeful thoughts. You can take the first steps to change by acknowledging your pain and hurt and deciding to seek help. You may also need to grieve for past hurts and losses.

It is one thing to have a desire for revenge on someone we do not care about, but what happens if it is someone you do want to have a close relationship with? Ted’s father knocked him about as a child, and yet Ted also loved his father and wanted to be close to him. In therapy, Ted found it extremely difficult to recognize the feelings of humiliation that his father had inflicted on him and his own desire for revenge. Until he did recognize this, he was not able to move on to forgiving himself, for his vengeful thoughts, and forgiving his father.

Sometimes a strong desire for revenge that is blocked can be associated with depression. For example, someone has been physically attacked in the street or seriously injured in a car crash, but the guilty person gets off with a light sentence or evades arrest altogether. When we feel a grave sense of injustice that we cannot put right, we can feel terribly frustrated and defeated. People who experience blocked revenge can be caught up in awful ruminations and feelings, often leading to difficulties in sleeping. This continual brooding keeps the stress system highly active, as they go round and round in circles. Even if they know this, they may be understandably reluctant to give up their pre -occupation. Professional advice and support may help.

Sometimes dealing with shame is about becoming assertive. For example Kimberly often felt shamed by her husband’s put-downs until she learnt to stand up to him. In working with depressed people we can find that shame and self-criticism can be covers for anger and that when they are honest about their anger the shame changes. For example, Anne’s mother was emotionally neglectful and very critical, but insisted that she was a wonderful mother. So wonderful, in fact, that Anne was never going to be as good as her at anything! Part of Anne loved her mother and was frightened of losing her support or igniting her criticism, but it was not until Anne acknowledged that there was also a part of her that would like to ‘smash her smug little face in’ (and give voice to that in therapy) that she was able to begin to think about assertiveness – being compassionate and understanding to that anger was key to helping with shame.

Shame is a very important emotion, but like all emotions such as anxiety, fear and anger it can become problematic. It can become too easily triggered, too intense and last too long (because of how we ruminate on our sense of shame). It can be associated with unpleasant memories, bodily feelings and a flawed sense of ourselves.

How we learn to recognize and work with shame is key to healing our shame, learning from it, growing from it and moving on. In this chapter we have seen a whole range of ways in which we can experience shame and deal with it compassionately. Shame is part of the human condition.