Many therapies focus on the importance of learning to cope with disappointments, setbacks and tragedies with forms of acceptance, coming to terms, not self-attacking and or not insisting on ‘it must’ or ‘must not’ – these are also old wisdoms.1

Our emotional reactions to frustration and disappointment depend on the importance we place on things. The most common are:

Disappointment is a major area where our shoulds and oughts (see page 454) come to the fore (as do our ‘musts’, see page 215). We can believe that things, ourselves or other people ‘should be like this’ and ‘should not be like that’. The problem here is that, life being what it is, it does not respect our shoulds and oughts. Some of us feel that we should not have to die, and instead of coming to terms with it, rage about the fact that life ‘shouldn’t be like this’. Sometimes our shoulds stop us from doing the emotional work we need to do, to come to terms with things as they are and work out helpful solutions for dealing with them.

We can develop a strong sense of ‘should’ when it comes to our own attitudes – about ourselves, e.g., ‘I should work harder’, ‘I should not make these kinds of mistakes’, ‘I should not be angry’, ‘I should love my parents and be more caring to them’ and feeling very disappointed when things don’t turn out as our ‘should’ says. Shoulds often involve anger and attempts to force ourselves to be different. When we rigidly apply the shoulds to ourselves, we inevitably end up bullying and attacking ourselves. It is as though we struggle to avoid accepting our limitations, setbacks or true feelings. In the 1940s the American psychotherapist Karen Horney called ‘the shoulds’ ‘a tyranny’.

When we apply shoulds to other people, we often feel angry with them when they disappoint us. Instead of seeing them as they really are, we simply say ‘they should be like this’ or ‘they shouldn’t be like that’ (see page 454). Strong shoulds often reduce our tolerance for frustration, and as we shall see shortly, shoulds and oughts can lead to serious problems with disappointment.

When you’re working compassionately it’s always worth asking yourself, ‘What’s the fear, what’s the threat behind my should, my ought or my must?’ There are not that many: they boil down to the fear of rejection or being marginalized, being shamed, being hurt or criticized, or a loss of control. It is because the threat system is involved that we often have problems with frustration.

Depressed people are often surprised when I suggest that ‘the secret of success is the ability to fail’. So much in our society concentrates on succeeding and achieving things that we can become fearful of, or even incompetent at failing. Yet, if you think about it, success, like love, looks after itself. Most of our problems don’t come from succeeding or doing well but from failing and not doing well. The way we cope with disappointment and setbacks can do much to throw us into depression, especially if we spiral into self-attacking and self-dislike. Learning how to fail without self-attacking can be a useful means of exerting more control over our moods. One reason why failure becomes a serious problem is because, perhaps without realizing it, we have become overly perfectionist and competitive people to whom the idea of failure is a terror.

Perfectionism relates to having high ideals and believing that we must reach them or else we are worthless and bad in some way. Research by the Canadian psychologists Paul Hewitt, Gordon Flett and their colleagues suggests that there are three forms of perfectionism:

Some forms of perfectionism are very helpful. You would like your brain surgeon to be a bit perfectionistic! Most of us accept that trying to do our best is a good idea. If something is worth doing, it’s worth putting some effort into it. The problem is: how much effort? Even if you work 20 hours a day, you might, in principle, say that you could have worked 21 hours a day. When we are in perfectionist mode, if we fail, we inevitably say we could have done more. The problem is clear – the goalposts keep moving.

It’s similar for ‘other-orientated’ perfectionists. Even if you put a lot of effort into something, if it is not exactly what they wanted, they will say that ‘you could have done more’. They can be very undermining – so watch out for them – they are often demanding and not always supportive of or able to appreciate one’s efforts. Children, for example, will have problems in judging what is reasonable effort and what is not.

Regarding our own judgements about ourselves, it’s not so much our desire for high standards – which can be driven by a passion to do well that causes trouble (see page 299) – it is when our perfectionism is driven more by fear of failure and fear of being criticized by other people and our self-criticism. Seeking high standards is important but once again it’s what drives this and what happens in us if we don’t quite make it; can we be self-accepting, kind, understanding and encouraging to ourselves in contrast to being very angry, self-critical and/or frightened of what other people think and will do? What is the true motivation for our drive to be perfect? If in our hearts we know that actually we drive ourselves because we are frightened, then we need to look at this – work on the fear. Research has shown that perfectionism is associated with a range of mental health problems, especially those linked with depression.

If you think you are a perfectionist then:

Frank, an artist, told me how he would fly into rages and rip up his work if he could not make the image that he had in his mind appear on the canvas. This is an example of perfectionism driving us into low frustration tolerance. Even in sex, perfectionists may be more focused on how they perform than on getting lost in the pleasure of it. They have to ‘do it right’. A patient of mine who used to go hiking, noted that he could have been walking anywhere; what seemed to matter more was how many miles he covered. He would set himself tests – ‘Can I walk 20 miles today?’ Even if it had been a bright and beautiful day and the countryside had been in full bloom, he would hardly notice this, because he was so intent in doing his set number of miles often as quickly as possible. Not very mindful!

At one level, we may see this as ‘gaining pleasure from achievement’. Such pleasures are short lived, do not stimulate the contentment/soothing system, and because the next ‘need to achievement’ pops up quickly we lose the ability to take pleasure for each moment – to be fully present (see Chapter 7). Of course, in depression, there is often a sense of not achieving enough and certainly a loss in the ability to enjoy the simple pleasures of life.

The disappointment and dissatisfaction with performances that perfectionists feel can result in a number of difficult emotions: guilt, anger, frustration, shame, envy and anxiety. These negative emotions can make life a misery. Even if successful, we know this may not be enough because we might think that people are only interested in us because of our success and not because they really care. Various famous people can get depressed with problems like this – success does not really give that sense of connection and belonging that they were looking for. To get those feelings we have to retrain our brains and reach out to others.

Ask yourself: Why do I want to reach the standards that I’ve set myself? You have to be really honest in your answers. Here are some that others have given:

It does not matter too much what your wants, wishes and hopes are, provided that you can cope with them not coming to fruition. If you say, ‘I’d like to impress others,’ that may be fine. But if you say, ‘I must impress others, otherwise they will see me as inadequate and I will feel useless and rejectable,’ you have a problem. And the reason why is that failure and setbacks will generate such anger with yourself and others that this can drive you into depression.

Here are some useful ways to cope with these difficulties. Keep in mind that some of your perfectionistic difficulties are fear-linked or simply bad habits. Make a decision to compassionately refocus your attention and practise the following:

Some people with eating disorders, who become very thin, are often highly perfectionist and competitive. They have a pride in themselves because they exert control over their eating and weight. Often the problem starts when they get on the scales, see that they have lost weight and feel a thrill or buzz of pride from the achievement. To put on weight produces a feeling of deflation and shame. They can become obsessed with every calorie and type of food they eat. This is an example of shame-driven pride. They may feel ashamed of their bodies or believe that there is not much about them to be proud of but then they hit on the idea of weight loss, and the pride of losing weight drives them on.

When shame turns into pride, it takes a real struggle to change this. Helping these people to put on weight may be seen as taking away the only thing (losing weight) they feel good at. This kind of problem is a very different one from, say, panic attacks. Nobody wants panic attacks, so therapist and patient can line up together against the common problem. Anorexic people want to be thin; they want to maintain their perfectionist standards of not eating much.

It is the same with all forms of perfectionism and competitiveness, be it cleaning the house, playing a sport well, working long hours and so on. The person does not want to give up these things. However, it is the reactions to failure and setbacks that have to be changed. If the sports person becomes depressed because he or she is not playing well and loses confidence in him/herself, that is hardly helpful. Many talented sportspeople do not make it because of how they react to things not going well – they can’t ride the ups and downs easily because anger and frustration disrupts their performance. They cannot refocus on the last.

There is an important motto for when we slip into perfectionism and overstriving – which is ‘what the Hell’. The fact of the matter is that once you have tried your best – if it’s not working – then ‘what the hell’ – you are not going to be taken out and shot by the Gestapo. It is finding that point inside you that lets you ‘relax, ease back and let things be’. Obviously I am applying this to perfectionism when we overly strive and get into states of panic, fear and depression. People who are lazy may need much less of ‘what the hell factor’ – so it’s always a matter of balance. But I and my own family have found that, at times, when things seem to be getting too intense, the ability to back off and think, ‘Okay, I’ve tried my best so what will be will be’ – ‘what the hell’ – is helpful. Technically this is called ‘de-catastrophizing and keeping things in perspective’ – but ‘what the hell’ – it works for me so I share it with you.

It would be great if we never felt frustrated, but while we might be able to lower our frustration threshold, the key is our ability to tolerate and work with it. That requires us to become more observant of how and when it arises in us. Our ability to tolerate frustration can change, for many reasons. You have probably noticed that, some days, you can cope with minor problems without too much effort, but on other days almost anything that blocks you can really irritate you. This is what we mean when we say, ‘He (or she) got out of bed on the wrong side today’. If we are driving somewhere in a hurry, we might see others on the road as ‘getting in our way’ and become angry. As our feelings and attitudes become more urgent, we start to demand that things ‘should be’ different from the way they are. Fatigue, tiredness and being under pressure are also typical everyday things that reduce our frustration tolerance. And depression itself can lower our frustration tolerance.

The degree of frustration that a person feels can relate to a fear of shame. For example, Gerry lost his car keys on the day he had an important meeting. He became angry with himself and his family because the keys could not be found. In the back of his mind, he was thinking, ‘If I don’t get to the meeting on time, I’ll walk in late. Everybody will think I’m a person who can’t keep to time and they will think I’m unreliable or careless.’ At times, we may blame ourselves with thoughts like ‘If only I were more careful, I wouldn’t lose things’. Probably everyone could tell stories of how, when things are lost (e.g., the string or scissors are not in the drawer as expected), they became angry and irritated: ‘Why are things never where they should be?’ When we get depressed our frustration tolerance goes down and coping with that can be difficult. Again keep in mind that this is not your fault, it is the depression – but it is helpful to work out how to cope:

One of the most important qualities of us humans is that we fantasize. This means that we are constantly making plans and developing fantasies of how we want things to be. The problem with fantasy is that we often live in excess. We imagine we can do more than we can. Often I have fantasized and imagined I could complete a piece of work in a certain time only to discover I couldn’t. Painters get frustrated when they cannot make the picture they are painting look like the one they have in their head. We often fantasize we are going to feel better than we do. For example, we might fantasize having a great fun holiday but it turns out to be just okay. Sometimes we fantasize about other people having fun lives and it is only us who are not. Fantasies can make us unreal-istic in many areas of our lives. The way we create our fantasies, ideals, wishes, anticipations and expectations in our heads can be absolutely crucial to our abilities to cope with the ups and downs of real life, life that rarely matches our fantasies.

Petro was a very bright student and throughout his life his single parent (and school) had admired his ability and praised him. But gradually Petro developed an idea that he needed to do very well, make his mother proud of him, be successful (not like his father) and one day rescue her from their poverty. This became linked to his self-identity. He fantasized about his career and going to the top universities. His school rather fuelled these fantasies. The problem was as his examinations approached and he had one or two lower grades he started to panic – seeing all collapse around him. He slipped into depression and could hardly work at all, seeing himself as a failure – yet he was a very bright lad! However, he was grossly over-extended and up on the high wire of life. Oliver James discusses these issues in detail in his book Britain on the Couch – of how too many of our children are being set up with too high expectations and who either give up, or crash when they fall short.

We can be set up for disappointment because our ideals, hopes and expectations are unrealistic. Modern Western societies are very unhelpful here because they imply you can be anything you like if you work hard enough. This is simply untrue. Genes, opportunity and luck as well as effort have a big effect on how our lives turn out. Often we have to learn to play the hand we are dealt – and sometimes that is a difficult one. Learning to do that with compassion can help enormously. A serious thwarting of our life goals and ideals can trigger depression, especially if we see this as having a lot of social implications (e.g., loss of status, loss of a loving relationship) as well as implications for how our lives will be in the future. Thinking about depression often means that we have to ask ourselves several questions:

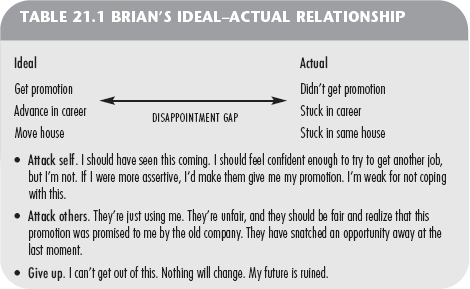

Spend a few moments thinking about your ideals. You’ll explore this more clearly by writing down the ideal and the actual in two columns (see table 21.1). You can then think about what I call the disappointment gap. The disappointment gap leads to four possible outcomes:

Because attacking is a common response to frustration, we can see that we have found a root source of our self-criticism – which is none other than our frustration. The more frustrated we are with ourselves, the more we may tend to bully and criticize ourselves. Keep in mind, as I indicated with the example above of Gerry (page 502) who lost his keys, that behind frustration can be feelings of threat, fear and anxiety – so always consider that as a possibility. Let’s work through some examples and see how this works.

Brian had set his sights on an important promotion. For over a year, he had worked hard to put himself in a good position, and his bosses had indicated that the promotion was within his grasp. He began to anticipate and plan how the new position would make his work easier and more interesting and how the extra money would allow him to move house. Unfortunately, two months before the promotion was due, Brian’s company was taken over and all promotions were put on hold. To make matters worse, the new company brought in some of their own personnel, and Brian found that the position he was going for had been filled by a younger man. He became angry and then depressed. All the plans, hopes and goals associated with the promotion seemed thwarted. He told himself that things never worked out for him and there was no point in trying to improve himself. He ruminated on the injustice of what had happened but had little power to change the situation – in effect, in his mind he kept fighting an unwinnable battle and thus saw himself as constantly frustrated and defeated. His ideal in contrast to his actual self looked like Table 21.1.

Of course it’s understandable why Brian felt bad about this lost promotion, but ruminating on his anger and self/other attacking made a bad situation worse. For him to come to terms with what happened – the fourth possible outcome – it helped for him to recognize his sadness about it (rather than block it out with anger) and the depth of his shoulds, and stop attacking himself. He soon realized that he could not have seen it coming and that it was not a matter of him not having been assertive enough. He gradually began to work out ways that he could get around this setback, waited a while and sought employment elsewhere. Coming to accept the situation and then working out how he could deal with it were important steps in his recovery. The more understanding, compassion and kindness one can bring to this situation the better – life can be very tough.

Depressed people often have the feeling that things have been spoiled. Susanne had planned her wedding carefully, but her dress did not turn out right and it rained all day. This was disappointing, but her mood continued to be low on her honeymoon. She had thoughts like, ‘It didn’t go right. It was all spoiled by the weather and my dress. Nothing ever works out right for me. Why couldn’t I have had one day in my life when things go right?’ She was so disappointed and angry about the weather and her dress that she was unable to consider all the good things of the day, and how to put her disappointment behind her and get on and enjoy the honeymoon. She dwelt on how things had been spoiled for her, rather than living mindfully in each new moment of her unfolding life (see Chapter 7). Later, when she considered possible positives in her life, she was able to soften her all-or-nothing thinking and to recognize that she was seeing the weather and the dress as almost personal attacks. She realized how her anger was interfering with her pleasure. She also acknowledged that many kinds of frustrations and disappointments in her life are often activated by thoughts of ‘everything has been spoiled’. She had to work hard to come to terms with her wedding ‘as it was’, but doing this helped to lift her mood.

The key process in these kinds of situations is:

The sense of things having been damaged and spoiled can be associated with the idea that things are irreparable and cannot be put right. In these situations, it is useful to work out how best to improve things rather than dwell on a sense of them being completely spoiled (which is linked to our anger). Of course, we might need time to grieve and come to terms with disappointments. One can’t rationalize disappointments away. The feelings can be very strong indeed.

Sometimes we can feel we are spoiling things for others because (say) of our depression or mistakes etc. That takes us back into the realms of shame and guilt (see Chapters 18 and 19).

When we fantasize about our ideal partners, we usually see them as beautiful or handsome, kind and always understanding. When it comes to sex, we may think that they (and perhaps ourselves too) should be like an ever-ready battery that never goes flat. When we think about our ideal lover, we don’t think about their problems with indigestion, the times when they will be irritable and stressed or take us for granted, or that they could fancy other people.

As an adolescent, Hannah had various fantasies about what a loving relationship would be like. It would, she thought, involve closeness, almost telepathic communication between her and her lover and few, if any, conflicts. She believed that ‘love would conquer all’. This type of idealizing is not that uncommon, but when Hannah’s relationship started to run into problems, she was not equipped to cope with them because her ideals were so easily frustrated.

The early courting months with Warren seemed fine and they got on well and Hannah was sure that theirs was going to be a good marriage. However, after six months of marriage, they had a major setback. The negotiations for a house they wanted to buy fell through. Then, while they were trying to find another, the housing market took off and they found that they had to pay a lot more for one of similar size. Warren felt cheated by life, his mood changed and he became withdrawn and probably mildly depressed. Hannah, who was also upset about the house problems, was more concerned about the change in her relationship with Warren. The gap between her ideal and the actual relationship started to widen. This discrepancy in her ideal–actual relationship looked like Table 21.2.

Gradually Hannah began to recognize that their problems were not about love but the hard realities of living. There was nothing wrong with her as a person or the relationship if Warren felt down. They had to learn to deal with their problems in a different way by encouraging each other to talk about their feelings. Hannah had often avoided this for fear that Warren would blame her or say that she was, in some way, part of the reason why he was feeling down. She also had to give up attacking him when he did not give her the attention that she wanted.

She slowly moved away from thinking that all problems in their relationship were to do with a lack of love. Warren had to acknowledge the effect his moods were having on Hannah and that he needed to work through his sense of injustice and belief that this was unfair and it shouldn’t have happened. They event ually learned to build on the positives in their relationship rather than fighting over the frustrations. Tough work, but compassionate openness can help develop the courage necessary.

So far we have discussed how we can be disappointed in things and people that block our goals and affect our relationships. Another key area of disappointment centres around our own personal feelings. Some depressed people go to bed hoping that they will feel better in the morning, and it is a great disappointment when they don’t. Unfortunately, when depressed we often feel (understandably) disappointed and deflated when we wake up and don’t feel any better but still anxious and tired. However, we can make matters worse by attacking ourselves, predicting that the day will go very badly and telling ourselves we ‘should’ be better. There are many other feelings that can be a source of disappointment. If this happens it can be useful to acknowledge this and engage in compassion under the duvet (see pages 151–2):

Let’s widen our scope a bit and look at some examples relating to disappointments with feelings. The following problem shows clearly how difficulties can arise when our hopes and ideals are disappointed by our own feelings.

Don had suffered from anxiety attacks for many years and, as a result, felt that he had missed out on life. He developed a strong fantasy that, if someone could cure his anxiety, he would be ‘like other people’ and especially more like his brother who was successful in the art world. When I saw him, I found that his attacks were focused on a fear of being unable to breathe and of dying. However, by looking at the evidence that he was not going to die when he had an anxiety attack, and learning how to relax to gain more control over his attacks, he made progress. In fact, he did so well that he went on a trip to Europe. But when he came back, he went to bed, got depressed, felt suicidal and very angry.

We talked about the problem as one of unrealistic ideals. Don had the fantasy that if his anxiety was cured he would do a lot of things and make up for many lost years. In his fantasy, he would be like others, able to travel, be successful and, in his words, ‘rejoin the human race at last’. He believed that normal people never suffered anxiety. He had hoped that there would be some magic method that would take the anxiety away, and that once it was gone, it would be gone for good. He explained that, on his European trip, he had suffered more anxiety than he’d expected.

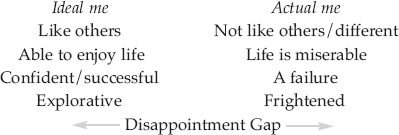

We wrote out two columns that captured this situation, headed ‘Ideal me’ (i.e. without anxiety) and ‘Actual me’ (i.e. how I am now).

Our conversation then went something like this:

Paul: It seems that you did quite a lot on your trip, but you feel disappointed with it. What happened when you got back?

Don: I started to look back on it and thought, ‘Why does it have to be so hard for me, always fighting this anxiety?’ I should have enjoyed the trip more after all the effort I put into it. I should have done more. It’s been a struggle. So I just went to bed and brooded on how bad it all was and what’s the point.

Paul: It sounds as if your experience did not match your ideal.

Don: Oh yeah, it was far from that.

Paul: Okay, what went through your mind when you found that the trip wasn’t matching your ideal?

Don: I started to think I should be enjoying this more. If I were really better, I’d enjoy it more. If I felt better, I’d do more. I’ll never get on top of this. It’s all too late and too much effort.

Paul: That sounds like it was very disappointing to you.

Don: Oh yes, very, terrible, but more so when I got back.

Paul: What did you say about you?

Don: I’m a failure. I just felt totally useless. After all the work we’ve done, nothing has changed.

Paul: Let’s go back to the two columns for a moment and see if I’ve understood this. For many years, you’ve had the fantasy of how things would be if you were better. But getting there is a struggle and this is disappointing for you. When you get disappointed, you start to attack yourself, saying that you’re a failure and it’s too late. That makes the ‘actual’ you seem unchanged. Is that right?

Don: Yes, absolutely.

Paul: Can we see how the disappointment of not reaching the ideal starts up this internal attack on yourself, and the more of a failure you feel, the more anxious and depressed you get?

Paul: Okay, it was a disappointment to have anxiety again. Were you anxious all the time?

Don: No, not all the time.

Paul: I see. Well, let’s start from the other end so to speak. If you had to pick out a highlight of the trip, what would it be?

Don [thinks for a moment]: There were actually a few, I suppose. We went to this amazing castle set up on the hill . . .

As Don started to focus on the positive aspects of his trip, his mood changed. He became less focused on the negatives and more balanced in his evaluation of the trip. I am not saying that you should simply ‘look on the bright side’ but suggesting you focus on the possibility that there may be some positives which offers some balance. It is easy to become focused on disappointment. By the end of the session, Don was able to feel proud of the fact that he had been to Europe, whereas a year earlier, going anywhere would have been unthinkable. He was not magically cured of his anxiety disorder. The more he focused on what he could do, rather than on how much he was missing out or how unfair it was to have anxiety attacks, the less depressed and self-attacking he became. Learning to be more mindful rather than fighting with, and being angry with his anxiety might also have helped him.

You might also notice something else here. If somebody has had a problem like this for a long time, it can become almost built in to their sense of self, their self-identity. Don believed that he was victim to anxiety and had missed out on life. This sense of being a victim to his anxiety was very strong and not easy to give up. If people see themselves as losers it can actually be quite difficult for them to see themselves as winners because it is too different an identity. Sometimes we have to be honest with ourselves and think whether we are trapping ourselves in an old identity. Are we really confident that we would feel okay about being a happy person? Can we allow ourselves to be happy in spite of difficult life circumstances?

We can feel that we have let ourselves down because we have not come up to our own standards or ideals. Here again, rather than accept our limitations and fallibility – that maybe we have done our best but it did not work out as desired – we can get frustrated and then go in for a lot of self-attacking. It is as if we feel we can’t trust or rely on ourselves to come up with the goods. We start attacking ourselves like a master attacking a slave who hasn’t done well enough. This frustration with oneself can be a major problem.

Lisa wanted to be confident, as she thought her friends were. She wanted always to be in a good state of mind and never feel intense anger or anxiety or be depressed. She had two clear views of herself – her ideal and her actual self (Table 21.3) – and these would go hammer and tongs at each other. She felt lazy because she couldn’t get motivated.

Lisa’s ideal self and her actual self were unrealistic. Her ideal self could not be met much of the time. Her actual self (which she identified as her depressed self) was prone to discount the positives, think in all-or-nothing terms and overgeneralize. Much of this was powered by frustration and fear.

It may be true that we can’t rely on ourselves always to be anxiety-free, or make the best of things, or be a mistake-free zone. The main thing is how we deal with our mistakes and disappointments. Attacking ourselves when we feel the anger of frustration is not helpful and, in the extreme, can make us very depressed. Learning to accept ourselves as fallible human beings, riddled with doubts, feelings, passions, confusions and paradoxes can be an important step towards compassionate self-acceptance. When disappointments arise, can we be understanding and compassionate? Anyone can be compassionate if it is plain sailing, but can you do it in a storm and when things are going wrong? That would be really helpful.

Fiona had wanted a baby for about three years. She would fantasize about how her life would be changed with a child, and she engaged in a lot of idealized thinking about smiling babies and happy families. However, the birth was a painful and difficult one, and her son was a fretful child who cried a lot and was difficult to soothe. She found it difficult to bond with him and, within a short time, became exhausted and felt on a short fuse. At times, she just wanted to get rid of him. She took such feelings not as a sad but not so uncommon experience of women after childbirth, but as evidence that she was a bad mother. When she could not soothe her son, she thought that he was saying to her, ‘You’re not good enough’. She thought that if she had been a better mother she would not have had a colicky child, and she would have been loving and caring from the beginning, regardless of her fatigue. She felt intensely ashamed of her feelings, and could not tell her family doctor or even her husband of the depths of her exhaustion or feelings of wanting to run away. She felt her feelings made her a bad person. The reality of life with her baby son brought a whole set of ideals crashing down around her head.

We can explore Fiona’s ideal of her motherhood and her depression (Table 21.4).

Let’s look at some kinder ways that Fiona might look at her situation, beginning with understanding and being compassionate to her distress. Here are some ideas for what she might reflect on and say to herself:

The moment Fiona faces her sadness, stops attacking herself and recognizes that she is not alone but may need help, she is taking the first steps towards recovery. Becoming depressed after childbirth is intensely sad and disappointing, and you can experience many odd (sometimes even aggressive, overwhelmed or want-to-run-away) feelings, but try not to be ashamed about them. To the best of your ability, be compassionate and kind with yourself, and reach out to others and discuss your true feelings with people around you and in particular your health visitor or family doctor.

One more point to keep in mind. If we’re having feelings of intense disappointment, say, there is often some bright spark who tells us to pull ourselves together, or who seems able to cope with everything. It may be someone in our lives who is being very critical of us, or who likes to tell us how well they coped with things and who can make us feel that we are a failure by comparison. Don’t be too influenced by these people (it might even be a parent). What we feel is what we feel, and rather than attacking ourselves, it is preferable to look at the ways we can cope and sort out our problems in the ways that best suit ourselves.

It is human to want to achieve certain things and create fantasies in our minds. However, these fantasies can become unrealistic because life is often complex and difficult. In this chapter we have noted how we can produce all kinds of fantasies and can create all kinds of hopes, anticipations and expectations. If these don’t come to fruition we can be disappointed. In our fantasies we often live a life of excess. Living in the reality of life can be tricky, but if we learn to be kind and compassionate, mindful and understanding, these can help us get through. Frustration and disappointment are not in themselves bad – indeed learning that we can’t have want we want when we want it is important for our maturity and wisdom.