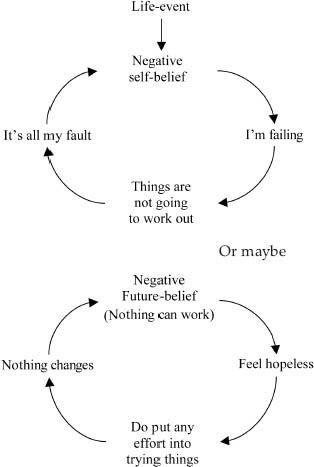

This chapter looks in more detail at the kinds of ways our thoughts can become problematic for us when we get depressed and how to work with them in a compassionate way. Depression can often be linked to difficult life situations: conflicts and problems in relationships, or at work, or with finances, or physical health, or feeling stuck in places we don’t want to be. Coping with these can be hard, but it can become even harder because as we become depressed, the way we think changes. Threat and loss-focused thoughts, interpretations and memories become much easier to bring to mind and dwell on. There is a shift to what is called a threat and loss (negative thinking) bias, and then we are on a downward spiral.1 A typical spiral is outlined in Figure 10.1.

As our thinking follows a downward spiral, we start to look for evidence that confirms or fits our negative beliefs and feelings. We may start to remember other failures, and the feelings begin to spread out like a dark tide rolling in to cover the sands of our positive abilities. Such thoughts tend to lock in the depression, deepen it and make it more difficult to recover from (see page 101). They drive a vicious circle of feeling, thinking and behavior – and this gives us one route into disrupting the depressing spirals.

Figure 10.1. A typical downward spiral.

Certain styles of depressive thinking are fairly common. Professor Beck, who started cognitive therapy, noted about six or seven types of negative (or as I prefer to called them ‘threat-focused’) thinking biases.2 We will explore some of them here. To work on our biases in a more balanced way, we have to (1) rec ognize them and (2) make an effort to bring our rational and compassionate minds to the problem. It is important to recognize that humans are often not that logical or rational – we can be, but we have to work at it. In fact a lot of research has shown that many of our ways of thinking about ourselves, other people, different groups, and our hopes for the future can become very biased and inaccurate – even at the best of times!2 So working for balance takes effort and training of our minds. Below we go though some typical biases that tend to appear with depression. We’ll start with jumping to conclusions because this is absolutely typical of the threat-focused and ‘better safe than sorry’ mind.

If we feel vulnerable to abandonment, or have the basic belief, ‘I can never be happy without a close relationship,’ it is natural that, at times, we may jump to the conclusion that others are about to leave us. This will often impel us to cling on to these relationships, unable to face up to our fear of being abandoned.

The part of our mind that focuses us on threats will tell us that we could not possibly cope with being alone. We might worry about how we think we could cope with everyday life, or we might worry about being overwhelmed by grief, feelings of loss and emptiness. Sometimes these feelings go back to childhood. If you have a fear of rejection or of losing a relationship, one way of helping might be to write down that fear and see if you can think of ways of coping with a break-up – if it occurs. Of course, the break-up may be painful: you can’t protect yourself from life’s painful things, but you can work out how to be supportive and compassionate to yourself in this time of difficulty. It’s hard but it can help us to actually shift our attention and think about how one could cope. For example, be understanding and kind to your distress: it is only natural to feel upset. We might consider how we could elicit help from friends, or remind ourselves that, before we had a relationship with this person, we had coped on our own; or that many people suffer the break-up of relationships and survive. There might even be advantages in learning to live alone for a while.

Another form of jumping to conclusions is called ‘mind reading’ or sometimes projection. We make assumptions about their thoughts and feelings. For example, we may automatically assume that people do not like us because they do not give suf -ficient cues of approval or liking us. In ‘mind reading’ we believe that we can intuitively know what others think.

The key point here is mindfully examining your thoughts rather than automatically assuming that your thoughts about what other people are feeling and thinking are accurate. Research has shown that some people struggle here. For example, parents may believe the annoying behaviors of their children are to wind them up; they take it personally. Or that disobedient children are showing that they don’t care about or respect the parent; again they take it personally. But they are reading intentions into their children that simply are not there. Young children are not thinking about ‘the mind of the parent’ at all. They are not thinking about how to ‘wind the parent up’ or cause them emotional upset – they are simply behaving in these ways to try to get what they want. It’s about them – the child – not the parent.

So the way we attribute intentions and feelings to other people’s behavior is important. When we get depressed we often think other people’s withholding, avoiding or ignoring behaviors are directed at us. Some men think that if their wives do not want to sleep with them when they want to it’s because they don’t love them enough – in reality there may be differences in sex drive, or timing or desire. Women may feel that if men don’t talk about feelings it’s because they don’t love them. In reality the man may have difficulties in talking about feelings in general. When people disappoint us it’s important to think that maybe it’s not really about ‘us’ or ‘me’ it’s about ‘them’. We have to find ways to be compassionately understanding and explore (take time to think about) the ‘minds of others’ in more detail.

We often need to be able to predict the future, at least to a degree. We need to have some idea about what threats, opportunities and blocks lie ahead to know whether to put effort into things or not. How much energy and effort our brains devote to securing goals depends a great deal on whether we have an optimistic or a pessimistic view of the future. It may be highly disadvantageous to put in a lot of effort when the chances of success appear slim. The problem is that, as we become depressed, the brain veers too much to the conclusion that nothing will work, and continuously signals: ‘times are hard’. Depression says, ‘You can put a lot of effort into this but not get much in return. Close down and wait for better times’ (see Chapter 3). Getting out of depression may involve patience and a preparedness to think that the brain is being overly pessimistic about the future.

Our brains have evolved over many millions of years to be able to have very strong emotions. One of our greatest difficulties is learning how to tolerate and come to terms with strong emotion. We can certainly look to how our thoughts may be making them stronger than they need be, but it’s also important to learn to tolerate the natural and normal power of our emotions; to rec ognize that there’s nothing wrong with us in having strong emotions. Rather it’s the way we deal with them, either by acting on them impulsively or by trying to get rid of them, avoid them, suppress them, or deny them that causes the difficulties.

A colleague told me a sad story he read in a local newspaper. A woman who was looking for her local Alcoholics Anonymous meeting got lost and couldn’t find the way there. She became upset, frustrated and anxious, so she sat in her car and drank a bottle of wine. She was picked up by the police well over the limit. She had simply not been able to tolerate the upset without wanting to turn off those intense feelings.

Another type of avoidance is the person who feels angry with a parent (say), but is frightened to acknowledge it or work through it. When anger arises she distracts herself or binge eats. Or a person may be frightened of (say) homosexual thoughts and feelings and so drinks to avoid them; or might drink to avoid feelings of loneliness or shame. We can run from all kinds of emotions. Our emotions can also stop us from doing things. Consider a socially anxious person who would love to go to university but the anxiety dictates their actions and they don’t go. Think about how often fears and worries stop you from doing things you really want to do. Sometimes we think about this in terms of confidence, but often it’s about our ability to tolerate emotions and act against that emotion. Most addictions, forms of self-harm, anxiety disorders, reckless and impulsive behavior and some depressions are linked to problems in tolerating emotions.

Given the problems we have with strong emotions and our ‘old brains’, distress tolerance is key to well-being. Compassion can be very helpful in how we learn to work with and tolerate strong emotions. Here are some ideas to have a go at.

When you have agreed your motivation then these are some things to try:

In these exercises you are practising buying time, being with your emotion, and tolerating it. These are just some ideas and you may find others once you have committed yourself to learning to tolerate strong emotion. It’s not easy, but over time it will get easier for you. Regular practice of mindfulness and compassion work can actually help us become calmer inside. You may also have your own ways of working on this issue. For example although I am not religious myself, I know it can help some people. One woman thought about Jesus: ‘If he can tolerate that, I can tolerate this’. She did not use this to shame herself about her emotion (there are no ‘shoulds’ and ‘oughts’ here), rather it helped her feel ‘one with the suffering of Jesus’ and was very helpful to her. A person who was trying to control her urges to eat when hungry thought about starving children in the world. If they can tolerate that, she could tolerate her urges. It’s not unknown for actors to have severe nausea, even vomiting, on the first night of a play, but they work through it because they really want to act. The first step is really getting clear in your mind the advantage of learning toleration, of putting up with painful feelings.

One of the reasons that we can have problems with emotion tolerance is because our emotions can be more powerful and long-lasting than they need to be. Strong feelings and emotions pull and push us into thinking in certain ways, and this can happen despite the fact that we know it is irrational. The problem is that, at times, we may not get our more rational and compassionate mind to help us. Given the strength of our emotions, we may take the view, ‘I feel it, therefore it must be true.’

Feelings are very unreliable sources of truth. For example, at the times of the Crusades, many Europeans ‘felt’ that God wanted them to kill Muslims – and they did. Throughout the ages, humans have done some terrible things because their feelings dictated it. As a general rule, if you are depressed, don’t trust your feelings – especially if they are highly critical and hostile to you. In Table 10.1 there are some typical ‘I feel it therefore it must be true’ ideas with some alternatives.

In their right place, feelings are enormously valuable, and indeed, they give meaning and vitality to life – we are not computers. But when we use feelings to do the work of our rational minds, we are liable to get into trouble. The strength of our feelings is not a good guide to reality or accuracy. See if you can come up with any other alternatives for the thoughts and ideas in Table 10.1.

Over 2,500 years ago the Buddha said, ‘Our cravings are the source of our unhappiness.’ He also suggested that it is our attachment to things, our ‘must haves’ and ‘must bes’ and ‘others must be as I want them to be’ feelings and beliefs that lead to suffering – not least because life is not like this. All things are transitory and it is coming to terms with that and living in ‘this moment’ that matters. Look out for feelings that indicate you are ‘must-ing’ yourself. As we become depressed, and sometimes before, we can believe that we must do certain things or must live in a certain way or must have certain things, e.g., others’ approval, or achieve certain standards, e.g., weight loss.

By gaining control over our musts, ‘got to haves’ and cravings, we are gaining control over our emotional minds. Whatever your own particular ‘musts’, try to identify them and turn them into preferences. Recognize that reducing the strength of your cravings can set you free, or at least freer, and remember that there is often an irony in our ‘musts’. For example, at times we can be so needing of success and so fearful of failure that we may withdraw and not try at all. If you go to a party and feel that ‘everyone must like you,’ the chances are that you’ll be so anxious that you won’t enjoy it and even may not go. And if you do go, you may be so defensive that others won’t have a chance to get to know you.

If we have been threatened or experienced a major setback, we may need a lot of reassurance before trying again. This makes good evolutionary sense: it is adaptive to be wary and cautious. We even have a saying for it: ‘once bitten, twice shy.’

The problem is that in depression this same process can apply in an unhelpful way. If we have experienced a failure or setback, we may think we need to have a major success before we can re -assure ourselves that we are back on track. Small successes may not be enough to convince us. However, getting out of depression often depends on small steps, not giant leaps. Typical automatic thoughts that can undermine this step-by-step approach are:

Remember what we have said about depression – your brain is working differently. Perhaps the levels of some of your brain chemicals have got a little too low. Perhaps you are exhausted. Therefore, you have to compare like with like. Other people may accomplish more – and so might you if you were not depressed – but you are. Given the way your brain is and the effort you have to make, you are really doing a lot if you achieve one small step. Think about it this way. If you had broken your leg and were learning to walk again, being able to go a few paces might be real progress. Depressed people often wish that they could show their injuries to others, but unfortunately that is not possible. But this does not mean that there is nothing physically different in your brain and body when you are depressed than when you are not.

If you can do things when you find them difficult to do, surely that is worth even more praise than being able to do them when they are easy to accomplish. We can learn to praise and appreciate our efforts, rather than the results.

A crucial thing to remember is that you are training and stimulating your brain. By focusing on small things that you can appreciate and give yourself praise for, you will stimulate important positive emotion areas of the brain. Although understandable, it is not helpful to keep dismissing these opportunities to stimulate your brain in a positive way. Try not to get caught up in debates with yourself about whether you deserve it, whether you should do more and so on. Focus on it as ‘physiotherapy for your brain’; exercising and stimulating key systems in your brain over and over again as often as you can.

Another area where we disbelieve the positive is when others are approving of us. To quote Groucho Marx, ‘I don’t want to belong to any club that will accept me as a member.’ Even being accepted is turned into a negative. Here are some other examples:

Rather than allowing himself to keep on thinking so negatively, Paul was encouraged to ask his boss about his report, especially the shaky areas. He didn’t get the response he expected. His boss said, ‘Yes, we knew those areas were unclear in your report, but then the whole area is unclear. In any case, some of the other things you said gave us some new ideas on how to approach the pro -ject.’ So Paul got some evidence about the report rather than continuing to rely on his own feelings about it.

From an evolutionary point of view, the part of us that is on the look-out for deceptions can become overactive, and we become very sensitive to the possibility of being deceived. Moreover, fear of deception works both ways. On the one hand, we can think that others are deceiving us with their supportive words and on the other, we can think that, if we do get praise, we have deceived them. Because deceptions are really threats, when we become depressed we can become very sensitive to them. But again we can try and generate balanced alternatives to these ideas. For example:

Even if people are mildly deceptive, does this matter? What harm can they do? I don’t have to insist that people are always completely straight. And life being life, some people are more deceptive than others. But I can live with that. To be honest I can be deceptive too – it is part of being human.

As a rule of thumb, it can be useful to take people at face value unless experience proves otherwise.

All-or-nothing thinking (sometimes also called either/or, polarized or black-and-white thinking) is typical when we are threatened. If we might be under a threat we often need to weigh this up quickly. Animals often need to jump to conclusions (e.g., whether to run from a sound in the bushes), and it is easier to jump to conclusions if the choices are clear – all-or-nothing. So our threat system can go for ‘better assume the worst’ and ‘better safe than sorry’. See if you can spot these in the list below.

All-or-nothing thinking is common for two reasons. First, we feel threatened by uncertainty. Indeed, some people can feel very threatened by this. They have to know for sure what is right and how to act and they may try to create the certainty they need by all-or-nothing thinking. Sometimes we may think that people who ‘know their own minds’ and can be clear on key issues are strong, and we admire them and try to be like them, but watch out. Hitler knew his own mind and was a very good example of an all-or-nothing thinker. Some apparently strong people may actually be quite rigid. Indeed, I have found that some depressed people admire those they see as strong individuals, but when you really explore this with them, they discover that the people they are admiring and trying to be like are neither strong nor compassionate. They are rather shallow, rigid, all-or-nothing thinkers who are always ready to give their opinions. A lovely motto someone gave me once was ‘indecision is the key to flexibility’.

There is nothing wrong with sitting on the fence for a while or seeing things as grey areas. Even though we may eventually have to come off the fence, at least we have given ourselves space to weigh up the evidence and let our rational minds do some work.

The other common reason why we go in for all-or-nothing thinking has to do with frustration and disappointment (see Chapter 21). How often have we thrown down our tools because we can’t get something to go right? When you get frustrated you tend to take a more extreme view. It is emotions that drive this view, so balancing of all-or-nothing thinking and our tendency to make extreme judgements of good/bad or success/failure can be very important in recovering from depression. The state of depression itself can reduce our tolerance of frustration and push us into all-or-nothing thinking, so we have to be aware of this and be careful not to let it get the better of us.

All-or-nothing thinking can be unpleasant for other people too. Tim talked about his mother who was depressed and how she found frustration very difficult. ‘Small things would set her off and then you would never know what mood she would be in.’ Tim could identify this as black-and-white and rigid thinking. ‘Things had to be just so and if they weren’t she’d get angry, anxious or withdraw.’ Tim understood that this related to various stresses in her life. Nonetheless, seeing this allowed Tim to reflect on himself and he decided he didn’t want to be like that. When he felt frustration mounting in him he would begin his soothing rhythm breathing, consider if his thoughts and feelings were rather black-and-white and practise being compassionate and tolerant in that context.

If one thing goes wrong, we can think and feel that everything is going to go wrong – our emotions go on a rollercoaster. When we overgeneralize like this, we see one setback or defeat as a never-ending pattern of defeats. Nothing will work; it will always be this way.

So it’s important to be aware of the arising of feelings and meanings and the thoughts that tumble along with them.

In Table 10.2 we can explore some typical balanced and compassionate alternatives for working on our tendencies for overgeneralization. Notice that we always start with being understanding and kind for the distress we feel.

In this situation, we have difficulty in believing that others have a different point of view from our own. The way we see things must be the way they see things – e.g., ‘I think I’m a failure, thus so must they.’ We discussed this on page 207, in the section ‘Putting thoughts into the minds of others’.

But there is another way we can be egocentric in our thinking. This is when we insist that others obey the same rules for living and have the same values as we do. Janet was very keen on birthdays and always remembered them. But her husband Eddie did not think in these terms; he liked to give small presents as surprises, out of the blue. One year, he forgot to buy a present for Janet’s birthday. She thought, ‘He knows how important birthdays are to me. I would never have forgotten his, so how could he forget mine? If he loved me, he would not have forgotten.’ But the fact was Eddie did not really know how important birthdays were to Janet because she had never told him. He was simply supposed to think the same way as Janet.

In therapy together with Janet, Eddie was surprised at how upset she had been and pointed out that he often brought her small surprise presents, which showed that he was thinking about her. He also mentioned to her – for the first time – that she rarely gave gifts except at birthdays, and to his way of thinking, this meant that she only thought about giving him something or surprising him once a year!

All of us have different life experiences and personalities, and our views and values differ, too. These differences can be a source of growth or conflict. It is because we are all different that there is such a rich and varied range of human beings. Unfortunately, at times we may downgrade people if they don’t think or behave like us. On the book stands today, you will find many books that address the fact that men and women tend to think differently about relationships and want different things out of them. This need not be a problem if we are upfront about our needs and wants and negotiate openly with our partners. It becomes a problem when we are not clear with them about our wants or we try to force other people to think as we do.

As we noted on pages 113–4, dwelling and ruminating on the threats and losses in our lives can be a source of maintaining your brain in a state of threat and stress. All the ways of thinking noted above can feed into ‘dwelling and ruminating’. Some people also think that this is a way to solve problems and, if limited, thinking things through can of course be helpful. However, going over and over things that upset you or make you angry or anxious is not helpful. The steps are: