We begin Part IV with the issue of approval because desires to be approved of, accepted, included, wanted, recognized, appreciated, valued and respected are often at the heart of many of our personal conflicts and worries when we’re depressed. When we explore other problem areas, such as shame, anger, disappointment and perfectionism, we will find that the issue of approval from others and fear of the opposite – criticism, rejection or marginalization – is often in the background, if not in the foreground.1

Before we explore how needs for approval are often tied up with depression we need to understand one thing. Humans have evolved to be a very social species whose very survival has depended upon the care, support and friendship of others. We even have special systems in our brain that monitor what we think others think about us, and will often try to work out if people like or don’t like us. Seeking approval is something all humans do. Otherwise, the fashion industry would get nowhere! Think, for a moment, what our world would be like if no one cared what others thought of them, if no one worried about gaining approval – and yes, there are some people who seem to be like that.

Feeling cared about and wanted can affect us in many ways. When we face crises or tragedies in our life it’s our ability to turn to others and feel supported and comforted by them that can help us get through. The problem is that because of early life difficulties or current life stresses, we can come to feel so alone and different that we become very dependent on other people’s approval and support. There is also good evidence that for some people not having anybody to talk to or share feelings with may be associated with depression.

We also know that in an effort to feel accepted and win approval people can sometimes become very submissive and focus on pleasing others. In that way they get out of balance with self-development and social connectedness. Yet other people who really would benefit from talking about their feelings and opening up to others actually close down and withdraw as they become depressed. This is sometimes due to feelings of shame, fear of being misunderstood or a sense of being a burden, or sometimes because, for them, being with other people means they would have to put on an act.

Much of our competitive conduct is related to gaining approval – whether it be passing an exam, winning a sports competition or beauty contest, or even having friends say nice things about our cooking. We often do these things to court other people’s approval, to feel valued. Children compete and compare over the latest cool clothes, music or video games. We want other people to see us as able, competent, or cool, to raise our status and standing in their eyes. Be it with bosses, friends or our lovers, we want them to think well of us. We also have a need to belong to groups and to form relationships, and so avoid being seen as inferior or rejected. Indeed, people will do all kinds of crazy things to win the approval and acceptance of others, be this of friends, parents or even God.

We can start to feel a bit depressed if we feel this competition is going badly and that compared to others we’re not doing so well. This takes us back to social comparison, discussed in Chapter 3 on pages 276–81. Feeling that other people are doing better than us can stimulate our envy and rumination and sense of inferiority. This in turn can drive the desire to win approval.

We are biologically set up so that other people’s approval and acceptance can help us feel good and their disapproval and rejection feel bad. However, we are likely to meet both during our lives and so we need to work out how to deal with both. Unfortunately, our need for approval can become a trap when we pursue it to an excessive degree. We can become rather submissive – overly trying to please others (people pleasers), panicky if we don’t and – worse still – self-critical. We also might not be able to cope with conflicts and disappointments in relationships. Even our nearest and dearest can be disapproving some of the time, or fail to notice things about us that we would like them to give special attention to. Sometimes they are just in a bad mood, of course. For example, Liz had a new hairstyle and hurried home to show Carl. He had liked her old hairstyle and was unsure about the new one, so he was cagey about whether he liked it or not. Liz felt deflated and started to think, ‘I thought he’d really like it but he doesn’t. Maybe I made a mistake. Perhaps other people won’t like it either. Why can’t I do anything right?’ Liz started to feel inadequate with herself and angry with Carl. Note how Liz’s disappointment turned into:

Can you see here how Liz’s disappointment and frustration is fuelling this self-criticism? Liz could simply recognize the disappointment and leave it at that, rather than use those feelings to be critical of herself.

A helpful way to cope could be to compassionately recognize and accept this as disappointment.

Oh, this is disappointing as I was hoping Carl would like it – so it is understandable to feel a bit deflated. He usually comes round, but even if not, I like my hair and it is helpful for me to start accepting what I like even if others are less sure. This is helping me become more my own person and this can help our relationship.

So learning to cope with this difficulty is actually an opportunity for growth.

Some people have feelings of inner emptiness if they do not constantly gain the approval of others. Wants, wishes and what were once thought to be good ideas seem to evaporate the moment another person does not go along with them or seems to disapprove. If this is the case for you, think about the possibility that you can start to find your own self by exploring your own preferences. Search inwards rather than outwards. Review the section on the empty self on pages 308–13. Ask yourself what things you can value that do not depend on other people’s approval. Even if someone disagrees, this is not ‘all-or-nothing’ – it is not the case that they are right and I am wrong.

When we become depressed, we can need so much reassurance that we become extremely sensitive to the possibility that others do not like or approve of us – they might be deceiving us. Sometimes we may engage in what is called mind reading2 (see pages 207–8). In this situation, rather small cues of disapproval are seen as major put-downs or rejections. A friend hurries past in the street and does not seem to want to talk to you. If you are depressed, you might think, ‘My friend does not really like me and wants to avoid me,’ rather than, ‘S/He seems rushed and hassled today’.

If you are unhappy with someone’s attitude towards you (perhaps because they were critical or ignored you), it is helpful to reflect and balance your thoughts. You can go through a number of steps. Remember, the first step is always to be understanding and kind to what we feel. If somebody criticizes you or doesn’t praise you when you were looking for it, acknowledge that this is upsetting. The more we are honest about our feelings, the more we will be able to work with them kindly. Once you have been kind, understanding and accepting of your feelings of disappointment or upset then it’s possible to stand back and think about your situation in a range of ways. Remember that standing back and using your compassionate and rational mind requires you to consider some questions in a kindly way, with a genuine desire to help you find balance in your thinking and not become more distressed than you need be. Try some questions like these. Ask yourself:

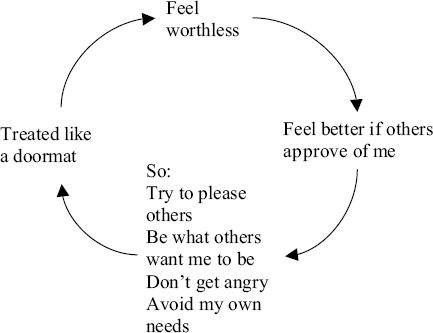

The subordinate approval trap often begins when you feel low in self-worth but you work out that you can feel better about yourself if others approve of you. You set out on a life’s task of winning approval – which, on the face of it, sounds like a good idea, but the way you seek to gain approval might involve various unhelpful things. For example, you might try to be what another person wants you to be. You might avoid owning up to your own needs or feelings. You might hide your anger. You might be overly accommodating, hoping that the other person will appreciate this. You might do things you don’t really want to do but don’t want to risk criticism or disapproval. This is a matter of degree, of course, because we all engage in these behaviors to some extent, but when we get depressed or when we are vulnerable to depression it can be to quite a large extent. Sadly, what can happen is that other people may get used to you simply fitting in, and the odd nod of disapproval can have you hurrying back to please them. You end up feeling like a doormat and worthless. You may also feel rather resentful after all the effort you put in. What do you do? Well, you’ll go back to your old strategies. You know how to deal with feeling worthless – you try to win other people’s approval, right? – and so around and around we go, as Figure 16.1 shows.

Figure 16.1 Feeling worthless circle.

Getting out of this circle requires that you are aware that you are in it, and that it is, to a degree, you who are setting yourself up for it. Next try to compassionately change the idea that you are worthless. Remember that this is a self-label (see Chapter 14) and is likely to be kept in place by your inner critic (see Chapter 13). Remind yourself that ‘worthless’ is a label and unhelpful. For the longer term your compassionate mind can support you in a journey of growth and change. This might start with gradually thinking about, recognizing and of valuing your feelings, learning simple acts of self-assertiveness, learning to see how you can enjoy some time alone and doing things you want to do.

Of course, approval may matter a lot when it helps us get a job or get on in a relationship. Again we’re all like this to a degree – so it is a matter of degree. However, a serious difficulty arises when we make negative judgements about ourselves if we don’t get the approval we want. Here’s an example: You put what you thought was a good idea to others at work, but they are not impressed and said that it was poorly thought out. A flush of feeling that sweeps through you directs your thoughts to:

What has happened here is that the disappointment and concern with the criticism has sent a flush of anxiety through you. If you are new to the team you may (understandably) want to impress them. We need to be kind, understanding and accepting of the anxiety and then not let our more extreme thoughts go through our minds unexamined or untested out. It helps to learn to cope with this because the chances are you’ll want to offer another idea at some point and don’t want to be so anxious that you can’t say what you want to say. Here are some compassionate and rational balancing ideas – but you may think of others that suit you better.

You could also be honest with yourself and think about whether your desire to impress did indeed mean that you were a bit rushed and didn’t think out your idea very well. If that’s true then it’s a useful learning experience. Be honest about that and move on with it. You might also notice some anger in being criticized.

When we make mistakes or get criticized it’s helpful for us to refocus our minds and not ruminate on them. What can we learn from the experience and how are we going to change our behavior in the future to be helpful?.

When we feel ourselves to be subordinate to others, that we are being used by them in a way we do not like, all kinds of changes happen in us. Beth and Martin had a good sex life. Martin was always keen, and at first Beth took this to mean that he really fancied her and she was a ‘turn-on’ to him. That made her feel good. However, gradually she came to think that, in other areas of their life together, he did not seem so caring. Eventually she had the thought, ‘I am just a body to him’. This thought, of being used by Martin, and being highly subordinate to his sexual needs, had a dramatic effect on her. She lost all interest in sex, became resentful of Martin and wanted to escape. Moreover, she felt that he had gradually taken over her identity and that she had lost her own. However, Beth’s thoughts got out of perspective as she became more depressed. Slowly she was able to change her thinking:

It had been Beth’s feeling used and unappreciated that had sparked off her negative feelings, but she had not had an opportunity to focus on them, challenge their extreme nature and take more control in her marriage. When she did this, she saw that there were indeed problems in the marriage, but she felt more able to try to sort them out. And perhaps she had rather allowed Martin to be inattentive for too long. What Beth also realized was that she and Martin needed to engage in more mutually enjoyable activities, not just sex.

A loss of identity can occur when we are in conflict about whether to live for ourselves or for others. Such conflicts can become all-or-nothing issues, rather than being faced as difficulties in balancing the various needs of each person in a relationship.

Nell gave up her job to have children and support her husband, but she gradually found this less and less fulfilling. Over the years, it had become accepted that her husband Eric should do all he could to advance his career, and in the early days, this had seemed like a good idea. But when he was offered a good promotion that involved relocation, Nell became depressed. What had happened?

Nell felt that she had lost her identity, she didn’t know who she was any longer and she wanted to run away. She didn’t want to move to another city but, on the other hand, felt she was being selfish and holding Eric back. Although for many years she had voluntarily supported him in his career, and at first had valued this, she gradually had come to think of herself as merely his satellite, spinning around him, and simply fitting in with his plans. However, she felt it was wrong to assert her own needs, and she was very frightened of doing or saying things that might be strongly disapproved of. Even her own parents said that she should do what she could to support Eric, and she worried about what they thought of her. As she became less satisfied with her position in the family, she found it difficult to change it because she thought she was being selfish and ‘ought’ to be a dutiful housewife. She thought that doing things that might interfere with her husband’s progress would make her unlovable. But re -locating and leaving her friends was a step too far. As for Eric, he was stunned by Nell’s depression, for he had simply come to expect her to follow and support him. He had not learned anything different. In fact, Nell’s depression was a kind of rebellion. But notice that this style had simply emerged between them and was nobody’s fault.

The first thing Nell had to do to help herself was to recognize the complex feelings and deep conflicts she was experiencing. I recommended that she watch the film Shirley Valentine – in which a housewife goes on holiday to Greece with a woman friend, leaving her husband behind, and then decides to stay on. I suggested she could consider her depression as a kind of rebellion: not as a weakness or personal failure (as she did at first), but as something that was forcing her to stop and take stock of where she was and where she was going. An important idea was to see the depression as making her face certain things, and although painful, could be an impetus for change. When she gave up blaming herself for being depressed, and telling herself that she was selfish for not wanting to move house, her depression lessened. We then did some of the exercises for the empty self (see pages 308–13).

Sometimes people feel that they have to accept a subordinate position because they have lost confidence in other areas of their lives. This was certainly true for Nell, so the next thing was to explore her loss of confidence with her. She wanted to go back to work, but felt that she was not up to it. Underneath this loss of confidence was a lot of self-attacking – for example, thoughts of, ‘I’m out of touch with work’, ‘It’s been too long’, ‘I’m not good enough’, ‘I won’t be able to cope’, ‘I might do things wrong and make a fool of myself.’, ‘Everyone is more competent than me’. Nell had also become envious of her husband’s success and his independent lifestyle, but again, instead of seeing this as understandable, she told herself that she was bad and selfish for feeling envious.

Confidence is related to practice. Think of driving a car. The more you do it, the more confident you will be. If you rarely drive, you won’t have the chance to become confident. It is the same for social situations. Women who have given up work to look after children can sometimes feel afraid of returning to work later in life. If this happens to you, think of whether you lack confidence because of a lack of practice. Be kind and compassionately gentle towards that. Avoid the tendency to criticize yourself. Work towards building your confidence compassionately, step by step. Get the evidence, rather than assume that you wouldn’t be able to cope. If you give up too quickly, it may be because you are self-attacking.

If you can come to terms with a possible loss of approval, this will place you in a better position than before your depression. Other people will not be able to frighten you with their possible disapproval. Always keep in mind, though, that wanting approval is absolutely natural – and the need may increase when we are stressed or depressed. It does for me. It is how we manage this that is key, not whether we have those feelings or not.

Kim was married to a wealthy businessman. Before she came to see me, she had been given medication and told that her depression was biological. She herself could not understand her depression – after all, she had as much money as anyone could want and her husband was not unkind. She thought she should be happy, but instead she felt weak for being depressed. Within a few sessions, Kim began to talk about how she had come to feel like a painted doll. She had to appear with her husband at important functions and often felt ‘on show’. Her husband was often away on business trips, and when he returned home tired, she felt that he used her to relax. She began to express her own needs, wanting to go to university and wear dirty jeans, as she said – but she also thought that her needs were selfish and stupid for a woman in her position and would court serious disapproval. She believed that, because her husband could provide her with any material thing, she was being ungrateful and selfish for wanting to live differently. She said, ‘Many people would be delighted to have what I have’. She also had many self-critical and self-doubting thoughts about going to university, for instance, ‘I’m too old now’, ‘I wouldn’t fit in’, ‘Others will think I’m odd’, ‘I’m not bright enough’, ‘I’ll fail’. Of course, she didn’t try to discover the evidence for any of these beliefs, and the depression was taken as proof that she would not be able to cope. They were more fears than facts.

When Kim began to help herself to get out of her depression, she started to:

Today I would do more compassion work too. Some people who feel highly subordinate to others can also feel so inferior that they think they don’t have the power to change. Once they can give up seeing themselves as inferior and inadequate, they open the door to change.

In a way, Kim felt as much subordinate to a way of life as to any particular person. Sometimes it is making money that causes problems, or maintaining a certain lifestyle. A couple may have become so dependent on money-making that intimacy falls away and tiredness rules. Both partners feel trapped by the demands to ‘keep going’. Sadly if relationships are subordinated to the need to make money, there is often a reduction in intimacy and happiness. There is increasing concern about these problems in our society today. The fear of losing a job can lead to working long hours; or there may be a need for two salaries. It is helpful to openly acknowledge this as a modern issue to be faced. Put time aside to ‘feed’ the relationship without this being seen as a burden. Gardens will grow whether you tend them or not but, if untended, you might not like the look of them as the years go by. Plan activities that are mutually rewarding and enjoyable. Spend time together on positive things, and show each other appreciation for sharing those things. Try to build on the positives rather than being separated by the negatives.3

Our need to feel approved of by others begins from the first days of life. For example, babies are very sensitive to the faces of their parents. If babies are happy and smile at their mothers and they smile back, the positive feelings between them grow. But if a mother presents a blank or angry face, the baby becomes distressed. When mothers and babies are on the same wavelength and approving of each other, we say that they are ‘in tune’ or are ‘mirroring’ each other. Indeed, in adult life, approval is signalled not only by the words people use but by the types of attention they give, the smiles, facial expressions and nods. A smile or a frown can say a lot, and a hug can do much to reassure us. When we get depressed we can become sensitive to non-verbal communication.

Not only can we withdraw into ourselves and become rather unappreciative of others when depressed, but our own nonverbal communication can be very unfriendly. We look grumpy and fed up most of the time, and rarely think about how this will affect others. Yet when others become distant, we feel worse. Unless you are very depressed, it is often helpful to try to send friendly non-verbal messages – to smile and be considerate of others. You may protest, ‘But aren’t you suggesting that I cover up my feelings, put on an act?’ The answer is yes and no. Yes, to the extent that you need to be aware that a constantly grumpy appearance is not a good basis for developing positive relationships – a depressed attitude can push others away. Moreover, if you smile and be friendly, this can affect your mood positively. However, the answer is also no, to the extent that, if there are problems that you need to sort out, then they need sorting out – don’t hide what you feel. Being grumpy or sulky and making no effort to be friendly actually sorts out very little – it can lead to brooding resentment in you and others.

We can get ourselves trapped in relationships and then feel depressed and stuck because we don’t want to upset people (see page 57).4 Steve had been made redundant, but a colleague he had worked for previously had set up a new business and invited Steve to join him. Steve had some doubts but needed the money and didn’t want to let his colleague down. A couple of weeks into the job, Steve’s concerns were realized. However, he felt his colleague had been very kind to help him out and that he would be turning his back on that kindness if he left – even though he now disliked the job. Steve became trapped by a sense of obligation, not wanting to let his colleagues down and also frightened they would see him as ungrateful. Gradually his sleep deteriorated, he became tired and anxious at weekends. Eventually, he was honest with his colleague who was very sad to see Steve go and tried to work out how to make the job better. However, Steve eventually found a job far more suited to his skills, and his depression receded in his new job. Sometimes our fear of upsetting people can trap us.

Of course there are many reasons for feeling trapped. For example, we may be in relationships we don’t want to be in but don’t have the money or alternatives to see a way out. Here it’s important to recognize the feelings of entrapment and then find people to talk to – perhaps a family doctor – to explore how to cope and resolve the difficulty. Recognize that feelings of entrapment are not uncommon in depression, that these feelings are not your fault, and that while they can be difficult, they are resolvable. Be cautious of thoughts such as ‘I shouldn’t feel like this’, ‘There is no way out’, ‘Things can’t change’. These are understandable feelings and thoughts, but if we are kind to them, acknowledge them but also explore around them, seek help, don’t take them at face value, we can never tell what lies ahead.

We can be so busy trying to gain approval and do things to please other people that we forget how to show appreciation of what they give us. For example, Lynne had a great need to be approved of. When I asked her how she showed that she valued her husband Rob, she said, ‘By doing things for him, keeping the house clean’. My response was: ‘Well, his approval of you makes you feel good, but what do you say to him about how you value him?’ Lynne went blank, then said, ‘But Rob doesn’t need my approval. He’s all right. Life’s easy for him. I’m the one who is depressed.’

When they were together, Lynne and Rob tended to blame each other for what they were not doing for each other:

Lynne: You never spend enough time with me.

Rob: But you’re always so tired.

Lynne: That’s right – blame me. You always do.

Rob: But it’s true. You’re never happy.

Around and around we went. Neither Rob nor Lynne could focus on how to offer approval to the other. Instead, they continually focused on their anger and thus there was little to build on. They rarely said things like ‘You look nice today’ or ‘It was really helpful when you did that’ or ‘I thought you handled that well’ or ‘You were really kind to think of that’. Lynne tried to earn approval but was not able to give it. It was painful for her to come to see that, in placing herself in a subordinate position, she felt that others should attend and approve of her, and she would work hard to get this approval, but she did not need to show approval of others. She saw them as more able than her and believed that her approval of them did not matter.

Depression can make us very self-focused in this regard. Sometimes depressed people are resentful of their partners, and giving approval and showing appreciation is the last thing they want to do. Don’t blame yourself for this but be honest and see what steps you can take to change. It can be useful, therefore, to consider how we can praise those around us – not just do things for them, but show an interest in them and recognize that all humans feel good if they feel appreciated and not taken for granted.

It is one thing to be criticized and to learn how to cope with it, but it is another to be on the receiving end of bullying. There is much literature on bullying and depression and an Internet search will reveal a lot of information, including advice on what to do. You could look at www.bullying.co.uk as a start. If you feel depressed because of bullying and want to escape, then recognize this as a normal response to bullying (our brains shift to threat mode big time) but get help; feeling bullied is even linked to suicide.

There is now much evidence that being on the receiving end of a lot of criticisms and put-downs (sometimes also called high expressed emotion) is associated with mental ill-health.5 These criticisms and put-downs can be verbal or non-verbal, or even physical attacks. Although it is common in depression to overestimate the degree and implications of criticism, it can also be the case that put-downs are not exaggerated. The problem then becomes whether anything can be done to change the situation or whether it is best to get out of the relationship.

Mark rarely said positive things to Jill, and acted as if he were disappointed in her. In therapy, he rarely looked at her but instead scanned the room as though uninterested in what was going on. Even when he did say some positive things to Jill, they were said in such a hostile and dismissive way that you could understand why she never believed him. The problem here was not only Jill’s depression but also Mark’s anger (rooted in his own childhood) and difficulty in conveying warmth. Many of his communications bristled with hostility and coldness; he saw depression as a weakness and was angry at Jill’s loss of sexual interest. She came to dread Mark’s moodiness and how he would look at her.

Sadly, Jill and Mark had become locked into a rather hostile and disapproving style. She experienced him as a disapproving, dominant male, and her life was spent trying to elicit his approval and get some warmth from him. When she failed, she blamed herself and became more depressed, with a strong desire to escape the relationship – which also made her feel guilty and frightened. She held the view that she should make her relationship work, regardless of the cost or how difficult it was. She prided herself on not being a quitter. But sadly, only if she subordinated herself to Mark’s every need could she elicit approval from him. Moreover, she came to believe that all men were like this.

Problems such as these often require relational therapy. However, if you blame yourself for the problems or are ashamed of them, this might stop you from seeking help. If you feel frightened and are not sure where the next put-down is coming from, whether in a close relationship or at work, it is possible that you are caught up in a bullying relationship. The degree of your fear can be a clue here – although consider whether you would be fearful if you weren’t depressed, because sometimes we become fearful of others because of depression. I have certainly come across many couples who fight a lot, feel resentful and so forth, but are not necessarily frightened of each other. So fear may be a key.

The first thing is to be honest with yourself and consider if a frank exploration of your relationship and its difficulties would be beneficial. Sometimes it is the bullying partner who feels ashamed about examining feelings of closeness and how to convey affection. Mark, for example, came from a rather cold and affectionless family and felt uncomfortable with closeness. He acted towards Jill in the same way that his father had acted towards him and his mother. As Jill came to recognize this, she gave up blaming herself for his cold attitude, and although this did not in itself cure her depression, it was a step on the way. She learned that trying to earn approval from a person who found it virtually impossible to give was, sadly, a wasted effort. Eventually the relationship ended.

So the lesson to be drawn from this is, don’t blame yourself for another person’s cold attitude towards you. If you do, you are giving too much power away to the other person. Research has shown that a woman still living with an abusive partner will often blame herself for the abuse inflicted on her, but will come to see it as not her fault if she moves away. Try using the ‘responsibility circle’ (pages 284–6) and see how many things you can think of that might be causing the problem. What are the alternatives for the other person’s cold attitude?

Obviously a more serious form of bullying is domestic violence. If this is happening to you then don’t suffer in silence; don’t self-blame or feel ashamed as sadly many people can suffer from this in their relationships. Reach out for help; for example, contact a national centre for domestic violence and speak to someone who can offer you support and advice (e.g., www.ncdv.org.uk). Remember the cardinal rules: honesty to your experiences, kindness and compassion for what you are experiencing, work out what you need to help you, give up self-blame and reach out to others.

There is increasing concern today at the amount of bullying that goes on in families, schools and at work (see www.bullying.co.uk). Being on the receiving end of a bully’s attacks can be pretty depressing. As a society, we need to learn how to be more accepting of others and less unkind. As individuals, we also have to learn how to protect ourselves as best we can from the effects of bullying.

You can sometimes spot a bully because you will not be the only one who experiences his or her behaviors as undermining. It can be useful to get the views of others – get the evidence that it is not just you. For example, in the case of Jill and Mark, many of their mutual friends saw Mark as a ‘difficult’ person. When Jill thought about this evidence, it helped her to give up blaming herself.

Bullies at work can be very upsetting, because you can dread going to work or feel yourself stirred up each morning. If this is the case for you then try talking to someone such as your union representative or works doctor or another manager. Talk to others about how they cope, see if you can learn anything and also so that you don’t feel alone with it; maybe form an alliance with others. If you are able to move away, do so. The key thing is to avoid shaming self-blame for your reactions – rather work with them in as helpful a way as you can.

One key problem is rumination. We often ruminate on the bully – what was said and what we should say, and how angry we are and having to face them again! Over and over it we go. That is very understandable but will constantly stimulate your threat and stress systems. If you can spot yourself ruminating, note this as understandable but not helpful – and switch to a compassion focus as outlined in Chapter 8.

If sexual harassment is the problem, specific individuals may be picked on. Others may not experience the bully in the same way. If this happens to you, again, obtain support from others and be as assertive as possible. Raise the issue as openly and frankly as you can at work. Don’t be stopped from raising the issue with thoughts of, ‘It’s only me’. You may need legal advice. The more you are able to discuss this with others, this easier it may be to work out how best to cope.