Depression is probably one of the darkest winters of the soul. Researchers throughout the world are trying to work out why we have this capacity to feel as terrible as we do – and many have come up with various explanations. We know that there are many different types of depression, with different causes and factors maintaining it. In this book, we have looked at some common types of depression. Whatever else we say about depression, it is clear that there is a toning down of the positive feelings and a toning up of our threat- and loss-based ones. The emotions of anger, anxiety and dread were originally designed to protect us. It is when they get out of balance that they can have unhelpful effects. One evolved protective strategy is to slow down and hide – try to recuperate. In depression, however, this ‘go to the back of the cave and stay there’ is not conducive to our well-being. Our energy takes a nose-dive, our sleep is affected and of course our thoughts and feelings about ourselves, others and the world we live in are dark. But fundamentally, depression is a brain state and brain pattern to make us lie low when things are stressful.

We now know that depression is a potential state of mind that has evolved over many millions of years. Many animals too can show depressed states. We also know that depression is very much linked to the support and acceptance of others and ourselves. We have evolved to be motivated to be wanted, accepted, valued and have status in our relationships. Depression is marked by inner feelings of being distant and cut off from others, with a sense of emotional aloneness.

What comes through from our understanding about depression, and many studies on our human needs, is that we have evolved to be very responsive to kindness – from the day we are born to the day we die. I outlined some of the evidence for this in Chapter 2. Kindness soothes the threat system and indicates helpful resources. This in turn reduces the ‘go to the back of the cave’ protection strategy. This is why it is so important to learn self-kindness, because your brain is designed to respond to it. Depression also relates to our desire to feel in control of our lives rather than controlled. Here are some key ideas.

Researchers are exploring what kind of self-help strategies depressed people find helpful. A review of this has recently been provided by two Australians, Amy Morgan and Anthony Jorm.1 They broke these strategies down into three groups:

1 Lifestyle strategies include taking exercise, trying to maintain a regular sleep schedule, increasing activities that are potentially enjoyable (as opposed to boring or dutiful), and recognizing the need for resting. In general this means acting against the push and pull of depression and anxiety. Also important is body care, such as healthy diet and avoiding toxic substances such as drugs that have any influence on one’s mood.

2 Psychological self-help includes focusing on rewarding oneself for small achievements, recognizing that many others suffer depression and visiting self-help websites (e.g., beyondblue, www.beyondblue.or.au is a partic u -larly good one), trying to break difficulties down into smaller problems, practising mindfulness and monitor -ing one’s thoughts.

3 Social strategies include trying to open up to other people, joining support and hobby groups and talking to somebody who has been through depression.

Interestingly, these researchers do not mention the importance of learning compassion to balance one’s mind. Although the Buddha recommended this nearly 3,000 years ago we are only beginning to recognize its power. When you engage in any of these self-help strategies, do it in the spirit of self-support, kindness and compassion.

In addition, think about regularly exercising your brain in the ways described in earlier chapters. There is increasing evidence now that practice may change your brain over time.2 However, like playing the piano or golf, you wouldn’t expect to be good at it first time out. Regular practice, however, will improve your abilities. It is the same with compassion.

Keep in mind also that your compassion practice will have three components (see Chapter 8):

1 opening yourself to compassion from others (including the use of imagery)

2 compassion that you practise for others

3 compassion for yourself.

However, we have also looked at the way we can train our minds, direct our attention, thinking and behavior in a compassionate way which is conducive to healing depression; changing the brain state of depression from one of low positive emotion to more balanced emotion.

When depressed we can feel life is meaningless – we are just oddities on a far-out planet; jumped-up DNA. Try not to get lost in this because 1,000 years from now we will see ourselves very differently. Many scientists are trying to answer the big questions: Why does the universe exist at all, rather than nothing? How can life evolve and why does consciousness exist? What is the meaning of life? We have no good answers! Your dog will never understand or be aware of existing in a material universe with planets. It will not have any notion of how your mind can think – because yours is so different. So there may be things way beyond our comprehension too, because our brains are limited. Don’t set yourself unanswerable questions. We simply cannot answer a question about ultimate meanings in a life process. Rather decide what gives life meaning for you in this lifetime; you may or may not have other lifetimes or types of consciousness. All you can do is focus on this life – right here, right now. Trying to understand your mind and learning the art of compassion for self and others might not be so bad a goal to make life meaningful. Certainly the depressed mind state is the last place you should look for answers to complex questions.

1 Seek help if you need it, don’t suffer in silence.

2 Go step by step.

3 Break problems down into smaller ones, rather than trying to do everything in one go.

4 Introduce more positive activities into your life.

5 Become more attentive and aware of your thinking and the ideas that go through your mind when you are depressed.

6 Identify your typical thinking styles (e.g., all-or-nothing thinking, discounting the positive aspects of your life). Note especially what you think about yourself, and how you label and treat yourself. Look out for your internal bully. Remember that this can drive you further into, rather than out of, depression.

7 Write down your thoughts to aid clarity and to focus your attention.

8 Identify the key themes in your depression (e.g., your need for approval, shame, unhappy relationships, unrealistic ideals, perfectionism). This will allow you to spot more easily your personal themes when they arise – and to challenge them.

9 Learn to work on your thinking with the use of your rational/compassionate mind. The more you treat yourself with compassion and give up thinking of yourself in terms of inferior, bad, worthless, and so on, the easier it will be for your brain to recover.

10 Try to work on negative thoughts and developing new ways of behaving. However, also expect setbacks and disappointments from time to time.

Finally, remember:

These states of mind are to do with how your brain was designed over millions of years. They are part of human nature.

Whatever judgements of ‘you’ that your emotions come up with, they are about as reliable as the weather. The more compassionate you are with yourself, the less you will be a ‘fairweather friend’ to yourself. If you can stay a true friend to yourself, even though depressed, you are taking a big step forward. You’re on the way up

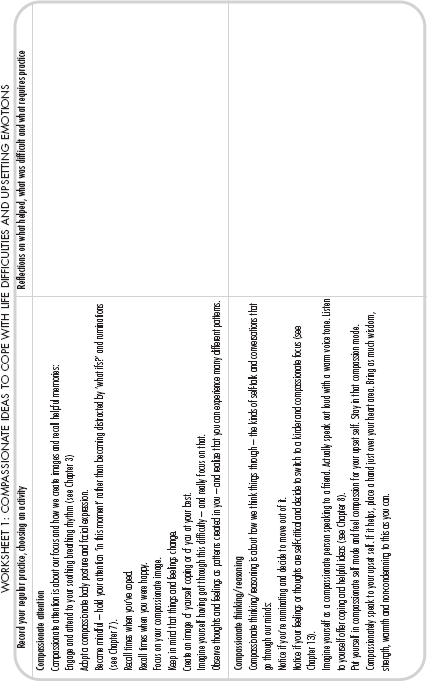

Over the next few pages you will see some worksheets that are designed to help you focus on different aspects of compassionate self-help. In essence we are bringing together many of the ideas we have discussed throughout this book. We’ve covered quite a lot of ground, so when you look at the worksheets you may feel they are a bit overwhelming. Don’t worry, however, just follow them through as best you can. You’ll see that they make some logical sense. The key always is to focus on what you think would help you.

The worksheets at the end of this chapter help you work with specific events and practice. When we are distressed we want to find ways to work with that stress or upset without making it worse. This means we need to think about our attention, how we approach the upset, how we think about this and behaviors to try and deal with it.

This worksheet offers various prompts and ideas designed to help you to practise refocusing your mind and accessing your soothing/contentment system. When threatened or upset, it’s easy to become focused on unpleasant feelings, worries or mem -ories. Recognize them, but also rebalance your system.

Remember the depressed mind will pull our attention and thinking towards loss and threat. We have to make a commitment to focus, think and act against our urges to do nothing, to avoid things, or to dwell on the unhappy things.

Keep in mind that this can be hard and stay as kind and compassionate to yourself as you possibly can – no matter how well or poorly you think you do with any of the following.

One important aspect of practice is how to do it. Probably the best way to begin is to start in small steps, or as big steps as you feel able. We can begin with what we called on pages 151–2 ‘compassion under the duvet’. This means that before you go to sleep and when you wake up spend some time focusing your mind on your soothing breathing rhythm, adopting a kind and friendly facial expression, and creating your compassionate self. The act of imagining that you are this self can be helpful. Of course when we are depressed it can be extremely difficult to get any feelings, or even to bother. However, it is the effort and focusing your mind on compassion that matters. Don’t worry if your mind constantly wanders – just bringing it back again is helpful. Try it for a week and see how you do. If you prefer, you can engage with your compassionate image.

Doing this for a couple of minutes each day (more if you can) might be enough to get you going. What you may find is that you become more aware of the possibility of compassion. When you’re at a bus stop, on a train or in the bath, or anywhere where your mind can run free, you might consider slowing your breathing down and then focusing on a compassionate exercise. Imagine what’s happening in your brain each time you do this. Imagine that those areas of your brain that are conducive to well-being and recovering from depression are being stimulated. As you get more into that practice, you may want to spend more and more time on it. For example, you might put aside 20 minutes or even longer each day, or a few days a week to focus on mindfully developing the feelings of compassion, practising directing compassion to others and to various parts of yourself. It’s useful to keep a journal so that you can see your practice developing over time. You may want to find other groups or retreats where you can take this further.

Keep in mind that we often bring compassion into life through action. For example, someone who is frightened of going out of the house will need to confront that fear at some point by going out. They are more likely to develop the courage to do this if they can attend to a kind, supportive and understanding voice in their head rather than the critical or panicking one. It is the same with depression. We are more likely to be able to develop alternative thinking, accept ourselves and our emotions, and act against our depression if we learn to attend to a kind and supportive voice in our heads rather than critical or pessimistic ones.

So it has been a long journey. Depression can indeed indeed be a dark night of the soul but with practice and compassion we can begin to light a few candles. May your compassion grow with you. We wish you well.