Game Theory, The Golden Bowl, and the Critical Possibilities of Aesthetic Knowledge

The eloquent models provided by economists are not limited to economics. Henry James’s The Wings of the Dove is one of the greatest modern works of art based on interdependent wills, reciprocal uncertainty, incomplete information, principal-agent relations, moral hazard, hidden actions and information, with one disastrous outcome holding in its net five persons whose wills have become interdependent in this game.

—Philip Fisher, The Vehement Passions

It’s a sign of the times: critics have been busy filling in the once-formidable crevasse between the ideal of the aesthetic—with an attendant sense of capacious consciousness, moral insight, expansiveness of perspective, affective appeal—and that of the economic—thrower of a Weberian net of instrumentalism, embodiment of sterile, dry rationalism. Nowhere has this project been more strenuously pursued than in the study of the Victorian novel, where the economic wing of the critical edifice has been built with remarkable energy by critics like Regenia Gagnier, Catherine Gallagher, and Mary Poovey.1 Their work differs considerably from the previously dominant conceptualization of the interplay between the economic and the literary, that on offer in the Marxist tradition, Frankfurt school variety. This field has turned against Marcuse’s or Bloch’s or Adorno’s invocation of the aesthetic in general, and literary art in particular, as providing a critique of and a utopian alternative to bourgeois, capitalist culture.2 Instead, these critics stress the imbrication of the literary itself with the discourse of political economy, rather than its critical or utopian function.

Although it’s rarely invoked by these critics, the case of Henry James is extraordinarily apposite to their project, confirming but complicating their insights. For just as he stood on both sides of the Atlantic (as biologically impossible as that may be), James stood firmly on both sides of the putative aesthetic/economic divide and deconstructed it avant la critical lettre. This is the writer who crafted for himself the position of High Culture novelist in the field of contestation that was late Victorian and early Edwardian letters; who articulated, in works like “The Art of Fiction” or the prefaces to the New York Edition, an elaborate formalist vade mecum not just for novelists but for those academics who followed in their path; and who spoke the aesthetic with extraordinary eloquence.3 But James was also a figure who openly did his best to realize “interest” on an investment in a literary life in the economic sense of the word. To read James’s letters or notebooks is to encounter the artist as avid professional, one who understood perfectly well that his art was a commodity and who attempted to sell it for the highest price on the open market: complaining about his failure to receive American royalties on his best sellers, Daisy Miller and The Portrait of a Lady; struggling to regain this audience by writing naturalist fiction or for the theater; wheeling and dealing with journal editors and publishers; turning with a mixture of despair and defiance to what I’ve called elsewhere a high art professionalism.4

James’s fascination with the economic dimensions of his vocation extended into the texture of his work as well. No writer I know has a greater sense of the power and possibilities of money to effectuate change in the world, in both a positive and a negative direction: wealth or the lack of it, the possession of money or the want of it, not only trace the limits but also limn the possibilities of freedom in James’s novels. No writer I know has at his disposal a more extensive arsenal of economic metaphors, particularly as he meditates on the nature and value of his own art itself. James’s life and work alike raise the very possibility Poovey in particular rules out of bounds: that writers of the high art variety did not need to “cloak their participation in the literary marketplace” but rather celebrated it; that a version of the literary that “emphasized originality and textual autonomy” can nevertheless offer a critical knowledge of the world not despite but by means of its tendencies to valorize itself as a closed system.5

In what follows, I want to use James’s The Golden Bowl both to explore these matters and to regard them with a different optic. Rather than looking at James through the lens of economic history, as do critics like Gagnier, Gallagher, and Poovey, I want to view James through that of economic theory, at least as economics has been theorized for the past five decades: abstractly, mathematically, even algebraically. Specifically, following but moving beyond Fisher’s suggestive but brief comments cited in the epigraph to this chapter, I want to weigh James’s representation of human behavior in the light of economic game theory—roughly speaking, the attempt to describe in symbolic or mathematical terms the strategies or “moves” that individuals pursue as they compete against or cooperate with each other to achieve a certain goal or end. James, I want to suggest, understands much of what game theory came to explore—and, more important, understood the things that game theory can’t address. My aim is not just to explicate James, but to trace the outlines and integuments of the aesthetic itself, at least of its literary incarnation. Rita Felski has recently argued—in highly, if unwittingly, Jamesian terms—that giving us a greater knowledge of the world is one of the things that literature can do: “The worldly insights we gain from literary texts are not … stale, second-hand scraps of history or anthropology. Rather, through their rendering of the subtleties of social interaction, their mimicry of linguistic idioms and cultural grammars, their unblinking attention to the materiality of things … they do not just represent, but make newly present, significant shapes of social meaning.”6 In what follows, I want to see how far Felski’s argument might be extended when literature as such is brought into contact with other disciplinary ways of knowing. The comparison, I hope to show, is not entirely to literature’s discredit.

To invoke game theory in the context of James is to embrace anachronism, since the text to which Fisher refers appeared in 1944, and the kind of game theory I will be describing was developed in the subsequent decades. So before proceeding, I need to sketch briefly the longue durée of systematic thought about games and competitive strategy and suggest how James enters into dialogue with that tradition. Games are, of course, as old as human beings; in the West they developed into an intimate part first of courtly then of middle-class life as part of what Norbert Elias called “the civilizing process.” Thereby, they accomplished the domestication of the warlike. What Elias sees as progressive movement from war to tournament to chess and cards—all of which mimic war (checkmate means “the king is dead”)—betokens the gradual development of culture toward mediated forms of combat.7 The same movement can be seen in the explicit theorizing about strategy. The early modern armchair general could, should he be interested in such matters, consult Caesar’s Commentaries, Flavius Vegetius’s De re Militare, or even Machiavelli’s The Art of War. Or that courtier, taken with the modish game of chess, could have studied the Roman de la Rose, in which the chess allegory mimics the battles of Charles d’Anjou; he might also have consulted De ludo scachorum, a thirteenth-century treatise that applied the rules of chess to the orders of medieval society. A few centuries later, a mathematically inclined cardplayer could have consulted a 1713 letter by mathematician James Waldengrave outlining a solution to a card game puzzle that historians take as the origins of game theory. A nineteenth-century intellectual could witness the application of these principles to other arenas of thought—Cournot’s Researches Into the Mathematical Principles of the Theory of Wealth (1838) or Francis Ysidro Edgeworth’s Mathematical Psychics: An Essay on the Application of Mathematics to the Moral Sciences (1881). The theorization of strategy moves from war to warlike games to the precincts of the library or the drawing room—and then back out again into a place where the public and the private, the domestic and the political, merge: the newly understood sphere of political economy.8

The same movement is evident in the elaboration of game theory. Originating in the research of brilliant (and fiendish poker-playing) mathematician John von Neumann, bearing fruit in 1944 with von Neumann’s publication (with Oscar Morgenstern) of Theory of Games and Economic Behavior, game theory moved quickly into the sphere of national security, especially via the efforts of the RAND Corporation, which, consulting with the defense department, used it to “game” the nuclear arms race of the 1950s. In the last twenty years or so, the theory that “won” the cold war has been utilized most fruitfully in the social sciences—political science, sociology, and especially economics, where its applications have been fruitful both in modeling large-scale systems and strategies of individual businesspeople. Indeed, it is in the last-named discipline that game theory has seen its most intense elaboration. With good reason, since in capitalism, every unit, as small as a Mom and Pop grocery store, as large as a multinational corporation, needs to anticipate the moves made by the competition and game out the best response.9

The same pattern is played by games qua games in the novel. For games of all sorts are foregrounded throughout The Golden Bowl in ways that bring the strategic and the social, the intimate and the economic, together. This transfer is fairly clear when, for example, the relatively transparent maneuverings of Fanny and Colonel Bob are depicted as moves in a game or when Guterman-Seuss, the Jewish antique dealer, lays out the object he has to sell, the damascene tiles, before Adam and Charlotte and is compared to a cardplayer laying down his hand. The most remarkable of these is a metaphor packed in near the end of the novel, where Maggie experiences a sudden pang of doubt as to whether Amerigo really will return to the room as they are saying farewell to Charlotte: “Closer than she had ever been to the measure of her course and the full face of her act, she had an instant of the terror that, when there has been suspense, always precedes on the part of the creature to be paid, the certification of the amount. Amerigo knew it, the amount; he still held it, and the delay in his return, making her heart beat too fast to go on, was like a sudden blinding light on a wild speculation. She had thrown the dice, but his hand was over the cast.”10 The passage bristles with conflicting economic forms of risk, ranging from lack of payment into the language of “speculation”—hers is a venture like all of those that had made fortunes for robber barons like her father, then morphs with a flick of the Jamesian wrist into the most speculative game of all, that of dice. And it’s this last metaphor—the one drawn from gaming—that unites all of these into one amalgam of behavioral, psychic, and economic intensities.

Not just the metaphoric but the actual representation of games enters into the text in the bridge-playing sequence at Fawns. Maggie is happy to be left out of the game, claiming to be singularly unequipped for cards and all they connote. Yet this is the sequence in which she scores one of her absolutely greatest triumphs: where Charlotte slips the bounds of propriety and confronts Maggie directly, and where Maggie successfully convinces Charlotte that she has no reason to reproach her. This scene suggests that James juxtaposes one set of ludic behaviors bounded by rules yet open to multiple strategizing—bridge—with another, equally rule-ridden game, that of custom. And, tellingly, when Maggie faces her first crisis—when she begins to suspect Amerigo of sleeping with Charlotte—she drops false modesty and uses precisely the language of cardplaying to gloss her response. “So had the case wonderfully been arranged for her; there was a card she could play, but there was only one, and to play it would be to end the game…. To say anything at all would be, in fine, to have to say why she was jealous; and she could in her private hours but stare long, with suffused eyes, at that impossibility” (349). Now there’s nothing surprising in the recognition that games play a crucial role throughout this novel, placing it in the tradition of the card-game-ridden novels of Austen, Dickens, Trollope et al.11 But the gap between Maggie as actual and metaphorical cardplayer points to the quality of The Golden Bowl that brings it closer to the worldview of economic-drive modernity than do even von Neumann and Morgenstern: its recognition of the divergence between games and competitive strategies. Maggie may or may not be all that good at the former, but she is a genius with the latter. What’s remarkable in the second book of the novel, after all, is that this seemingly naive, artless girl outmaneuvers the infinitely more sophisticated players who face her at the card table, including a supersubtle Roman Prince, a world-historically successful millionaire, and a penniless beauty who has had to live by her wits. Maggie does so precisely because, while they play, she thinks (“you know it’s my nature—I think”), and Charlotte and the Prince, clever though they may be, underestimate this capacity: they “thought of everything but that I might think” (569). Crucially, “thinking” here is not defined as an Isabel Archer–like accession to an amplitude of consciousness but rather a cold assessment that leads to the formation of a plan of action. However emotional she may be, Maggie also anticipates, assesses, strategizes: “She had a plan, and she rejoiced in her plan” (343). And in so doing she transvalues the idea of strategy itself, augmenting its move from the warlike to the economic by extending it into the realm of intimacy.

I want to gloss Maggie’s actions in the novel—and the responses they elicit—by means of two quite basic abstractions offered in the game theory tradition, the game tree and the Prisoner’s Dilemma game. The idea of the game tree is deceptively simple: it traces out the possible moves one player can make in a game, each move setting up in turn another series of choices (represented as nodes) to which one’s opponent can respond … and so on to the end of the game, at which a win, a loss, or a draw can be easily represented with a symbol like, say, +1, -1, and O (for win, lose, and tie respectively). Since each set of initial decisions creates a series of ensuing moves, following out each branch of the game tree in each case can suggest to a given player what the likelihood of success might be in a given move. A game tree for, say, tic-tac-toe is relatively simple (see addendum); a game tree for chess, with its greater number of variables, is infinitely more complex, and so must be the attempt to harness game theory to the behavior of those infinitely complex entities, human beings. But there’s yet one more complexity relevant to James’s novel. Game theory also accounts for situations of asymmetric information—situations in which one player has more information than the other, as when a player cannot know what move his or her predecessor has already made. In such situations, the second player has only one recourse: to work retroactively—to attempt to calculate probabilistically on the basis of what a player is doing, what that player has already done. The more one can grasp about what a player does in the present, the more one can construct the strategy he/she has followed in the past, and the more accurately one can anticipate his/her moves in the future.

This describes Maggie’s situation exactly and suggests the kinds of tactics she adopts. Her situation is that of the player in a game in which the other players have already initiated the action, to which she is compelled to respond in a kind of epistemological void. “Moving for first time as in the darkening shadow of a false position” (329), Maggie decides to do something “just then and there which would strike Amerigo as unusual,” “small variations and mild manoeuvres” undertaken however “with an infinite sense of intention” (331). She sets out quite consciously to undertake actions that will provoke a response and she gets one: the momentary flicker of uncertainty that greets her presence at their house, where in any normal relation she would be, rather than at her father’s and Charlotte’s, where he expects to find her. And she displays a subtle calculatingness in this process. “She had only had herself to do something to see how promptly it answered,” Maggie muses (343, emphasis mine): in other words, she makes a move not just to bring about another move but in order to assess, via the rapidity of Amerigo’s response, what is motivating him—what, in other words, his original move (the affair with Charlotte) had been. After betraying himself with his initial hesitation, Amerigo’s countermove is brilliant: he embraces her. By thus acting as if nothing has happened between them, as if the status quo of their relationship could be restored with a simple embrace, he deprives her of any further information she needs to plan her own response. As he continues to do: pages later, Maggie muses over his changed behavior: “He was acting … [on] the cue given him by observation; it had been enough for him to see the shade of change in her behaviour: his instinct for relations, the most exquisite conceivable, prompted him immediately to meet and match the difference, to play somehow into its hands” (353). The point to be made here is double: not only is the Prince able successfully to counter Maggie by “meeting” and “matching” the difference in her behavior, but Maggie understands this about him. There’s an element of detachment in her love even as there’s an element of love in her detachment.

Amerigo’s countermove blocks hers, as if he plays an o in a tic-tac-toe game that prevents the x from filling a row—a stratagem which, however, doesn’t cause the game to cease, but freezes it in place, allowing her only to fill in more x’s to be countered by more o’s and so on to infinity. In order for her to break the stalemate, in order for her to attain the kind of knowledge she needs—in order, that is, to win—Maggie needs to test Charlotte, as she proceeds to do: “Of that inevitability, of such other ranges of response as were open to Charlotte, Maggie took the measure in approaching her, on the morrow of her return from Matcham, with the same show of desire to hear all her story” (346). Her cleverness here consists in making Charlotte go over the narrative ground of the affair not so much to hear the truth about it, since Maggie knows that Charlotte would never communicate that, but to be able to “take the measure” of Charlotte’s “ranges of response”—to figure out what kinds of moves she is making in the present in order to understand the moves she has made in the past and hence what Maggie can do in the future. And after Charlotte responds more or less as the Prince has done, happily recounting a lying version of their time in Gloucester, Maggie counters by conspicuously spending time with her stepmother, assaying “the experiment of being more with her” (349). The alacrity of Charlotte’s response to Maggie’s overtures, like the Prince’s embrace, allows Maggie to measure them: such sudden shifts in behavior indicate to Maggie that their “demonstrations” are “determined”: willed, strategic.

They thereby designate that there is something for Maggie to be suspicious of: “By the end of a week, the week that had begun especially with her morning hour in Eaton Square between her father and his wife, her consciousness of being beautifully treated had become again verily greater than her consciousness of anything else … [of the] impressions fixed in her as soon as she had so insidiously taken the field, a definite note must be made of her perception, during those moments, of Charlotte’s prompt uncertainty” (349–50). And from this she is able to move further, to the recognition that Charlotte and the Prince are acting together—a perception that nails into place her sense of their commonality:

The word for it, the word that flashed the light, was that they were treating her, that they were proceeding with her—and for that matter with her father—by a plan that was the exact counterpart of her own. It wasn’t from her they took their cue, but—and this was what in particular made her sit up—from each other; and with a depth of unanimity, an exact coincidence of inspiration, that when once her attention had begun to fix it struck her as staring out at her in recovered identities of behaviour, expression and tone.

(354)

Brilliant as the deduction is, something in Maggie hesitates here to take matters to their logical conclusion, a hesitancy that lasts many chapters. This can be read as a sign of the persistence of her flawed innocence—of that state of blissful ignorance that has helped to construct the problematic ground of both of the marriages that structure the book and from which she needs to grow in the rest of the book. But when viewed in game theory terms, we can understand Maggie’s passivity more fully. Maggie’s options exist, as it were, on the left side of the tic-tac-toe game outlined earlier. One option is to lose the game (-1; or even -2): should she confront the two, either they would continue to deny her suspicions and make her look ridiculous or, worse, confirm them, costing her her marriage and, perhaps more problematically, wounding her father. A second option is to do nothing; a course that seems irrational, to be sure, but preferable to the alternative. In this version of the game, Maggie’s moves are matched symmetrically by the Prince and Charlotte’s countermoves, leading inevitably to a draw, the reassertion of the status quo (which would be expressed mathematically as the outcome 0). Maggie’s behavior, then, is perfectly rational—a 0 outcome being preferable to a −1. But to say this is, at the same time, to confront the harsh quality of the choices that confront her. After all, the status quo that is the source of the problem is, in the first place, a life in which Maggie is fixed, isolated: “The ground was well-nigh covered by the time she had made out her husband and his colleague as directly interested in preventing her freedom of movement. … Of course they were arranged—all four arranged; but what had the basis of their life been precisely but that they were arranged together? Ah! Amerigo and Charlotte were arranged together, but she—to confine the matter only to herself—was arranged apart” (357). Her strategic insight, in other words, only reveals to Maggie the bars of her prison, not a way to escape it.

But there is another way to succeed. The basic presupposition of hers, as of all games, is that its players are rational—that they play within the constraints set by its rules (e.g., x and o alternate turns in tic-tac-toe; knights move differently from rooks). What happens, however, when one player starts breaking the rules—moves out of turn, advances a pawn three spaces instead of one? According to von Neumann and Morgenstern, the game as such is over: “the rules of the game … are absolute commands. If they are ever infringed, then the whole transaction by definition ceases to be the game governed by those rules.”12 This is what happens when Maggie discovers the depth and extent of the Prince and Charlotte’s history with each other via her visit to the antiquario’s shop and the antiquario’s return visit to her. The constraints of the game up until now have been that she can make no direct accusation of Charlotte and the Prince—as she puts it, “she had but one card to play, and to play it would be to end the game” (349). But in this moment she shockingly does just that, first to Fanny, then to the Prince himself. In so doing she breaks this formal vessel of the game structure as thoroughly as Fanny has done the bowl.

But to recognize this is to imply as well that a new game can then be established, one in which there are new rules, rules that might potentially be more advantageous to the player stalemated by the old ones. And this is what Maggie does, constructing a game that was later to be labeled the Prisoner’s Dilemma. In that grim structure we are asked to imagine that two people suspected of a crime together are imprisoned separately. Both are told that there’s enough evidence to convict them, but that their testimony against the other would clinch the case. They are then given the same set of choices: rat out their collaborator and, if the collaborator remains silent, go free; remain silent and, if their collaborator is also silent, receive a lighter sentence; remain silent and, if their collaborator confesses, receive the heaviest sentence possible. The optimal outcome for both is to remain silent—an alternative we might think of as cooperation in the economic and human spheres alike. But the optimal outcome for each is to confess and so implicate the other, since this will result in, at worst, a light sentence and at best freedom—an alternative we might think of as competition, again in both the economic and human spheres. As each contemplates his or her choices, then, betrayal seems the only rational thing to do, however dismal a comment this might be on human nature: as the Prince tells Maggie, “Everything’s terrible, cara—in the heart of man” (582).

Maggie creates a version of the Prisoner’s Dilemma—with an insidious twist. Having herself known what it is like to feel imprisoned and isolated by conditions of asymmetric knowledge, she turns these conditions on those who made them for her and offers the Prince a Prisoner’s Dilemma choice. When she indicates to the Prince that she has evidence of his perfidy—the shards of the Golden Bowl, the testimony of the antiquario—and then immures him in a state of epistemological doubt when she answers his question, “does anyone else know?” with the challenge “I’ve told you all I intended. Find out the rest—!” (472), James’s metaphorical language is explicitly that of enchainment: she feels “with the sharpest thrill how he was straitened and tied, and with the miserable pity of it her present conscious purpose of keeping him so could none the less perfectly accord” (465). But the implication is that, in so framing the matter this way, she is offering him a bargain. Maggie will returns to the status quo if he will forsake Charlotte and return as an engaged participant to his marriage:

“Yes, look, look,” she seemed to see him hear her say even while her sounded words were other—“look, look, both at the truth that still survives in that smashed evidence and at the even more remarkable appearance that I’m not such a fool as you supposed me. … Consider of course as you must the question of what you may have to surrender on your side, what price you may have to pay, whom you may have to pay with, to set this advantage free; but take in at any rate that there is something for you if you don’t too blindly spoil your chance for it.”

(461–62)

It’s true that what Maggie wants least is an outright confession—“if that was her proper payment,” she thinks at the end of the novel, “she would go without money” (595). What she wants instead is an acknowledgment of her change, an acknowledgment that will facilitate the construction of a new marital relation of equals; this would come, however, at the price of his tacit acknowledgment of wrongdoing and his abandonment of Charlotte. The alternative is a much heavier, even unthinkable, punishment: an outright breach, which would presumably leave the Prince impecunious and disgraced. Now, as in all Prisoner’s Dilemmas, there is the chance the Prince might be able to bluff his way through, especially given the tacit understanding on the part of everyone that Adam is to be spared the knowledge of the perfidy of his wife and his son-in-law—this seems to be the implication of the Prince’s first question to Maggie when she confronts him. But such a chance depends on too many variables. Under the circumstances, he makes the right choice, abandoning Charlotte and accepting the lighter sentence, a future in which he knows his wife knows that he is capable of betraying her but chooses to be with him anyway.

But Maggie’s efforts do not halt here. She also constructs a twist on the Prisoner’s Dilemma scenario: she offers only one of the prisoners a choice. Maggie isolates Charlotte, imprisoning her as effectively as she does Amerigo; but she never offers Charlotte the bargain that she presents to her husband. Indeed, to the contrary, she systematically withholds the very possibility of choice from her betraying friend: although Charlotte, a brilliant reader of others, knows that something has changed in Maggie, and knows as she must that Amerigo is no longer her collaborator, she is kept from the knowledge of exactly what has happened between them through lies at once explicit and implicit. This condition, explicitly understood as an imprisonment—the “cage” of a “deluded condition” (493)—reproduces, ferociously, the conditions to which the Prince and Charlotte have submitted Maggie (“Maggie, as having known delusion—rather!—understood the nature of cages” [493]): like Maggie in the first half of the second book, Charlotte is put in the position of the second player in a game who has to guess at what the first player has done in order to make her own moves.

Unlike Maggie, who is throughout, without perhaps realizing it, the subtler strategist and the better mind, Charlotte opts for direct confrontation, “a grim attempt” (493) at breaking out of the prison cage, first in the card game scene, then in a direct sally as she hands her back a book. Indeed, forcing Maggie either to accuse her or deny that she has any such accusation to make is precisely the move that Maggie had decided early on not to make with the Prince; when Charlotte makes it, she doesn’t see, or doesn’t care anymore to see, that the chain of decision nodes works in such a way as to suggest that she keep quiet. Assuming the worst—that Maggie knows—she faces the following possibilities: if Maggie accuses her, she and Maggie both lose (-1, -1); if she doesn’t, Maggie may win or she may not, the status quo will at any event be preserved (-1, 0). Either way, the smart move is to do nothing: although this too might lead to a loss, it might prove to be closer to a draw than a loss.

Alternatively, Maggie might not know, and the changed behavior that Charlotte observes might be due to any number of factors; in this case, Charlotte and she will either keep the status quo, or Charlotte will give away her own guilt by word or deed in order to confirm a knowledge that is only, at the present, a suspicion; we would represent this as a decision matrix of (0, -1). Here again, the wise course of action is to do nothing, to remain suspended in a state of epistemological vertigo, which is the cruel price the situation demands. But, as it was for Maggie, the rational course of action is also the unendurable one—and unlike Maggie, who possesses both epistemological and financial power, Charlotte is not in a position to change the rules of the game.

Which isn’t to say that she doesn’t try. Her direct confrontation at Fawns is also an attempt to get Maggie to offer her some clear choice, like the one that Maggie has offered the Prince with her challenge:

“I’m aware of no point whatever at which I may have failed you,” said Charlotte; “nor of any at which I may have failed any one in whom I can suppose you sufficiently interested to care. If I’ve been guilty of some fault I’ve committed it all unconsciously, and am only anxious to hear from you honestly about it. But if I’ve been mistaken as to what I speak of—the difference, more and more marked, as I’ve thought, in all your manner to me—why obviously so much the better. No form of correction received from you could give me greater satisfaction.”

(506)

The word correction brings together the thematics of truth, knowledge, and punishment that play against each other throughout the novel: what Charlotte challenges Maggie to do is to offer her a version of the deal Maggie has sketched for the Prince, “correction” in exchange for a light sentence. We can see why she would wish to do so. Charlotte has, even more perhaps than the Prince, something to offer in exchange: Maggie’s continued access to her own father. By implicitly turning to blackmail, Charlotte is pushing on the edge of the game, just as Maggie has; she’s like a prisoner quite literally here, but one who is trying to turn the tables on her captor in the interrogation room. Again, Maggie proves to be the superior player. Although she is indeed willing to pay this price, she won’t make that willingness explicit, preferring instead to keep Charlotte captive, controlled, corrected in the prison of her ignorance and her love. She does so perhaps out of a bit of cruelty—what better revenge could there be than to use the victimizer’s tactics against her?—but also out of a sound strategy. That she has something to bargain with suggests to Maggie that Charlotte needs to be kept out of even a Prisoner’s Dilemma choice: it suggests to Maggie the depths of Charlotte’s guilt, the dimensions of her betrayal, and hence hardens her heart against her former friend. It also suggests to her Charlotte’s courage, her bravery, and hence further positions Maggie in a situation where she daren’t show any vulnerability.

Her next move is fully, forcefully, and explicitly to lie—an act that bests Charlotte irrevocably, for, not only does it render any of her countermoves irrelevant (what does she have to move against?), it formally reties the bond between Maggie and the Prince on their shared complicity in the gulling of Charlotte:

Maggie had to think how he on his side had had to go through with his lie to her, how it was for his wife he had done so, and how his doing so had given her the clue and set her the example. … They were together thus, he and she, close, close together—whereas Charlotte, though rising there radiantly before her, was really off in some darkness of space that would steep her in solitude and harass her with care. The heart of the Princess swelled accordingly even in her abasement; she had kept in tune with the right. … The right, the right—yes, it took this extraordinary form of humbugging, as she had called it, to the end. It was only a question of not by a hair’s breadth deflecting into the truth.

(507–8)

The point is clear: Maggie’s strategic genius shows her how to operate within the socially constricting rules as well as within the affectional confines of her own weird family; but its chief use is to demonstrate to her the limitations of the games she has been forced to play. It’s not until Maggie starts breaking the rules, becoming an irrational player, and then making up new ones that her efforts are crowned with success.

To be sure, the novel registers victory in the conjoined language of game playing and economics I have been stressing, first in the metaphor of dice throwing I have previously quoted and then in Amerigo’s embrace of her one last time, when the “truth” of her triumph “so strangely lighted his eyes that as for pity and dread of them she buried her own in his breast” (595). At this final moment all the themes I have been trying to bring together here are reprised, one last time, and brought together in a unity that proposes they are all versions of the same thing. If Maggie has triumphed through her gamesmanship, then she has both won her husband and, as her father does in his own way, transformed him into an object, a pawn, or a card in her hand.

It’s this moment, I think, that not only validates the aesthetics/economics link but also extends it into our own time. Maggie’s successful deployment of ludic strategies anticipates the kinds of intrusion of economic strategizing into the precincts of private life that is the hallmark of the current moment. James’s novel adumbrates the kind of work done by Nobel laureate Gary Becker, who famously suggested just how much of what passes for responses to the people we love and desire—our fathers, our lovers, our partners—is shaped by the same tactics that govern the actions of hedge fund managers, millionaire investors, entrepreneurs, and so on. But, in so doing, The Golden Bowl also provides a powerful critique of those tactics and their results, and on two counts. First, it’s important to remind ourselves that Maggie only wins the game by fixing it—by altering its rules to fit her own agenda, and she can do this not only because of her superior savvy (her recognition that continuing to play by the rules will lead to defeat) but also because her wealth and position give her the power to make a new game. The only way to be sure to win, in other words, is to make sure that yours is the only game in town; and the only way to do that is have the power to set the rules themselves—a power granted Maggie in no small measure because of the dependence of the Prince on her fortune.

Second, there is a very real question about the nature of her victory. What, exactly, has she won? Contra some readers of the novel and the triumphalist rhetoric of the last pages, it seems clear in the final lines of the book that she has achieved, more or less, nothing. Her father and her best friend are lost to her, immured in an exile to which she sends them as sacrifice and punishment; she has won again the love of her husband, but he seems to be as much a hypnotized automaton as an active participant in their marriage. Having been acquired by Adam as a present to his daughter, all but seduced by his passionate former lover, the Prince now switches his allegiance to his wife, but doesn’t seem to display any more will than he had previously. What Maggie learns, in other words, is how to win at the game of her life and her marriage; but this is a loss-loss outcome (-1,-1). To win is to lose; it is to best Charlotte but to become troublingly akin to her; to regain your husband, but at the price of rendering him an inert object of your own will rather than the passive object of someone else’s.

Anticipating the brave new world of game theory that was to prove so important to contemporary economic thought, and anticipating even more acutely the extension of economic analysis into understandings that have followed it of the transactions of everyday life, the novel thus presciently critiques these developments, putting in their place a view of life in which precisely the means that assure victory ensure defeat, those that allow for the accomplishment of gain negate it. And in doing so The Golden Bowl vividly displays the kinds of knowledge that fiction has to offer in a world where the economic has risen to social hegemony, as it was beginning to do at James’s moment, as it has done more thoroughly over the course of the long twentieth century to our own. But, to conclude with one last turn of the screw, by making this gesture of critique, James anticipates one of the directions in which economic thought is beginning to travel. Underneath the rise of economism in the past thirty years as I’ve adverted to it, there has been another tide rolling through the field, a critique of the model of rational choice and marginal utility upon which game theory relies and to which James’s novel poses pointed questions. The former has undergone sustained critique by the school of behavioral economics that poses the Jamesian question, in the words of Richard Thaler and Sunil Mullainathan, of “what happens in markets in which some of the agents display human limitations and complications?”13 Far from being rational agents capable of making the best possible choice from available alternatives, human beings are driven by cognitive frames and emotional needs into wholly irrational, self-balking behaviors. Recent work in economics has included stringent criticisms of the reigning models of economics on the score of information control. Understanding that the most basic claims of economics rely on the impossible ideal type of perfect transparency of knowledge between partners to any transaction, large or small, economists like Joseph E. Stiglitz (awarded the Nobel Prize in 2001) have stressed the ways that asymmetries of information play out in matters as crucial as the setting of wages and as mundane as bargaining at used car lots; in a more popular vein, Steven D. Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner have written a national best seller devoted to probing such questions as how real estate brokers use their greater knowledge of the market to more attractively price their own houses than they do those of their clients.14

The point here isn’t that James anticipated Freakonomics or should have shared in Stiglitz’s Nobel; it is, rather, that the self-critical turn in recent economic work brings it into territory that has been explored by James: a world in which the line between the intimate and the economic has been irrevocably blurred; a world where a complex blend of the rational and the irrational guides the strategies that individuals pursue as they enter into complex blends of competitive and cooperative behaviors; a world in which competitive strategies are shaped by asymmetries in information; a world, indeed, where information is capital itself, to be hoarded when possible, deployed with devastating effect when necessary.

But there is one more turn to this particular screw. For economists have been reconsidering the making of their own discipline, seeing the literary as offering precisely the terms and capacities for explicating the nature of the field, for explaining the economic behavior of individuals, or—most important—for providing vital access to knowledge in and of itself. The first of these moves I associate with Deirdre McCloskey, who has been writing of economics as a rhetorical and narrative practice for many years (although, admittedly, with less effect within her profession than she would have liked).15 The second I associate with Robert A. Shiller, mainstream Yale economist (and the man who called correctly not one but two bubbles, that of the stock market of the 1990s and the real estate market in the 2000s), who has given narrative—that is, collectively authored stories without any necessary reference in fact—pride of place in accounting for the shaping of the irrational action of markets.16 For the third, I would cite Tyler Cowen, a Harvard-trained libertarian at George Mason University, who compares literary with economic modeling and sees the former as providing what the latter lacks.17 Representing heterodox, mainstream, and neoclassical schools of economics, respectively, their endeavors taken together suggest that the future of economic theory may well lie in the attempt to rethink the basic tenets of the discipline in such a way as to recognize the power of that species of knowledge production (i.e., narrative or literary) that seems most antithetical to it. What Maggie knew, or what Henry knew, in other words, suggests to them what the literary knows, what the aesthetic can teach: that art makes interest in all senses of the word, reflecting and reflecting on how we buy and sell, capitalize and consume, and that, in so doing, it makes knowing our currency and information our futures.18

Addendum: The Prisoner’s Dilemma in The Golden Bowl

Nan Zhang Da

As noted, Maggie waits until the golden bowl is broken to design a Prisoner’s Dilemma (PD) for Charlotte (CH) and Amerigo (A). She opts to use this strategy to corner CH and A because, while the golden bowl is evidence of their relation, in itself it is insufficient as a piece of incriminating evidence. A PD is usually only employed if the interrogator does not have enough evidence to punish the prisoners for their suspected crimes and/or desires additional information. The beauty of this, as of all game theory, is the principle of mechanism design. By designing a game and coercing/asking players to participate, the mechanism design can always get players to reveal the truth, whether or not there is in fact a falsehood: hence its optimality for Maggie’s unusual situation.

By definition, a PD has to be performed simultaneously: each prisoner given the same amount of time and information, each denied access to the other. James models this as closely as possible by having M approach A and CH with the shortest possible time gap, while making sure A and CH cannot collaborate and, more important, give each other emotional/psychic/facial signals that might let the other know where one’s true preferences lie.

The logic behind M’s PD is as follows:

A prisoner in the PD must always find his optimal strategy in confessing (C) even though his team’s optimal strategy is to not confess (D/C). This has to hold even given the following caveats: 1. uncertainty on the part of any one or both of the prisoners in a PD over the preferred treatment of the other (uncertainty signified as μ); 2. the probability that the other prisoner has more or less information (information asymmetry).

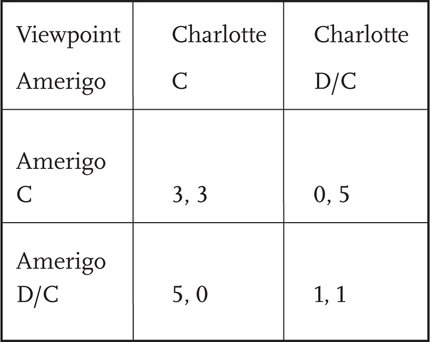

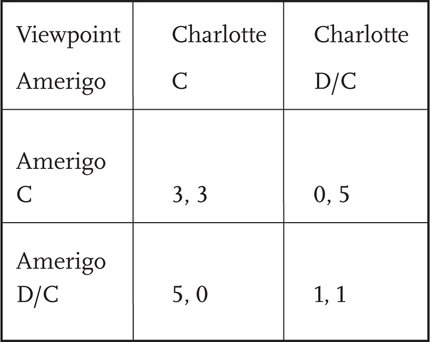

Or, represented below in a PD payoff matrix:

For Amerigo and Charlotte, for each to confess while the other one remains silent is the optimal payout (0); to both remain silent is less optimal (1), to both confess is even less optimal (3), and to remain silent if the other confesses the most punitive (5).

Confession is all but beside the point in the PD M designs for A. The true “mechanism design” of the PD for A is the conveyance of a message from M, who needs to formulate and deliver the message when she is in the state of not knowing A’s true preferences. That message is deceptively simple: I will stay married to you no matter what. Its genius is that the open-endedness of the promise also has buried within it a time constraint: Maggie implicitly adds: “or so it seems, for now.”

In dealing with CH, M’s tactic must consist of two parts:

1. M has to convince CH that A is not on CH’s team anymore, so that CH will cease to consider a scenario in which she leaves Adam but runs off with A. If, though, A has “confessed,” she cannot be sure that an interlude with CH will not see an impulsive change of heart.

2. M can never know for sure what A’s true preferences are and thus can never know for sure if CH knows what A’s true preferences are. Simply “telling” CH that A is no longer her partner has its obvious risks. M can only convince CH that A no longer prefers to play with CH by conveying the impression to CH that A similarly went through a PD (with a clearer payout structure) and made his decisions against CH.

M creates a modified PD for CH, where one of the prisoners (here, A) receives preferential treatment not in the terms of the payout structure but in having more (or more complete) information about that payout structure than the other M cannot create a true PD for CH because, unlike the interrogator in the classic PD, she has constraints that sharply limit the extent to which she can enforce her “punishments.” In technical terms, she does not have the ability to make good on certain parts of the payout structures she has designed for A and CH—and CH knows this. The genius of PD, though, is that the minute one of the prisoners in PD confesses, the enforceability of the PD for the second prisoner becomes irrelevant. The outcome is the same.

Notes

1. Regenia Gagnier, The Insatiability of Human Wants: Economics and Aesthetics in Market Society (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000); Catherine Gallagher, The Body Economic: Life, Death, and Sensation in Political Economy and the Victorian Novel (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005); Mary Poovey, Genres of the Credit Economy: Mediating Value in Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century Britain (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008).

2. See inter alia Georg Lukács, from his pre-Marxist “romantic anticapitalist” phase, The Theory of the Novel (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1974); Walter Benjamin, “The Storyteller: Reflections on the Work of Nicolai Leskov,” in Illuminations, trans. Harry Zohn (New York: Schocken, 1970), 83–110; Herbert Marcuse. The Aesthetic Dimension: Toward a Critique of Marxist Aesthetics (Boston: Beacon, 1979); Theodor Adorno, Aesthetic Theory, trans. Robert Hullot-Kenter (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1998); and, perhaps more relevantly, Adorno’s gem of a discussion of Dickens in “On Dickens’s Old Curiosity Shop,” in Notes to Literature, vol. 2, trans. Sherry Weber Nicholson (New York: Columbia University Press, 1992), 171–77. For Fredric Jameson, see Marxism and Form: Twentieth Century Dialectical Theories of Literature (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1974), and The Political Unconscious: Narrative as a Socially Symbolic Act (Cornell: Cornell University Press, 1985).

3. Henry James to H. G. Wells, July 10, 1915, quoted in Philip Horne, Henry James: A Life in Letters (London: Penguin 1999), 555.

4. Jonathan Freedman, Professions of Taste: Henry James, British Aestheticism, and Commodity Culture (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1990). Michael Anesko has shown how James’s early and middle years comport withto this pattern in “Friction With the Market”: Henry James and the Profession of Authorship (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987). For the effect of this on his work, see Marcia Jacobson, Henry James and the Mass Market (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1983).

5. Poovey, Genres of the Credit Economy, 418.

6. Rita Felski, Uses of Literature (Oxford: Blackwell, 2008), 104.

7. These themes are developed most fully in Norbert Elias and Eric Dunning, Quest for Excitement: Sport and Leisure in the Civilizing Process (Oxford: Blackwell, 1986).

8. See Robert W. and Mary Dimand, “The Early History of the Theory of Games from Waldengrave,” in E. Roy Weintraub, ed., Toward a History of Game Theory (Durham: Duke University Press, 1992), 15–29.

9. John von Neumann and Oskar Morgenstern, Theory of Games and Economic Behavior (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004 [1944]). As William Poundstone has observed, this may be the most unread famous—and famous unread—book of the twentieth century, and while the author of this essay has made a valiant try, he can’t claim to have followed its mathematical proofs with the greatest of acuity. Indeed, he has followed the advice of the authors, who suggest that the mathematical proofs need not necessarily be followed for the argument to be persuasive (11). He has relied on secondary works to flesh these out, most notably William Poundstone, Prisoner’s Dilemma: John von Neumann, Game Theory, and the Puzzle of the Bomb (New York: Anchor, 1993), which offers a lucid explication not only of von Neumann but of the Prisoner’s Dilemma problem set, and Morton Davis, Game Theory: A Nontechnical Introduction (New York: Dover, 1997).

10. Henry James, The Golden Bowl, ed. Ruth Bernard Yeazell (London: Penguin, 2009), 594. Further citations in the text will refer to this edition.

11. For a good summary of these, see Michael Flavin. Gambling in the Nineteenth-Century Novel: “A Leprosy is O’er the Land” (Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 2003).

12. Von Neumann and Morgenstern, Theory of Games, 145.

13. Sendhil Mullainathan and Richard Thaler, “Behavioral Economics,” MIT Department of Economics Working Paper Series, Working Paper 00–27, September 2000. http://www.economics.harvard.edu/faculty/mullainathan/papers_mullainathan (accessed April 15, 2011).

14. See, for example, Joseph E. Stiglitz, Whither Socialism? (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1994); Steven D. Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner, Freakonomics: A Rogue Economist Explores the Hidden Side of Everything (New York: William Morrow, 2006).

15. This has been a constant theme in McCloskey’s writing of the last twenty-five years. See “The Literary Character of Economics,” Dædalus 113 (1984): 97–114; The Rhetoric of Economics (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1985); Knowledge and Persuasion in Economics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991).

16. Shiller elaborates on the role of narrative in George A. Akerlof and Robert J. Shiller and Akerlof, Animal Spirits: How Human Psychology Drives the Economy, and Why It Matters for Global Capitalism (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009).

17. Tyler Cowen, “Is the Novel a Model?” in Sandra J. Peart and David M. Levy, eds., The Street Porter and the Philosopher: Conversations on Analytical Egalitarianism (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2008), 319–37.

18. A shorter and somewhat different version of this essay was delivered at “American Literature’s Aesthetic Dimensions,” a conference held at the Huntington Library in 2007; I profited from numerous comments and questions from the audience there. Thanks to Sara Blair, Kerry Larson, Cindy Weinstein, and Christopher Looby for reading this essay, in some cases numerous times, and for making helpful suggestions for its revision, some of which I’ve even followed!