The Beauty of the Book in the Poetry of Susan Howe

A scrap of Emily Dickinson’s “cream laid” notepaper traced with graphite, the face of the manuscript buffed and eroded by time and the friction of the oblong envelope (acid free) in which it is stored.

A strip of denuded gray homespun or of the muslin once used for bed curtains, the fabric threshed by time to a mere crosshatch of warp and woof: porous, skeletal.

The ambered tissue of a nineteenth-century frontispiece overleaf.

A crushed, torn origami, one friable finger’s length, shaped like a weathervane, ripped from a Webster’s dictionary, 1840 edition, tiny crumbles sifting from the edges.

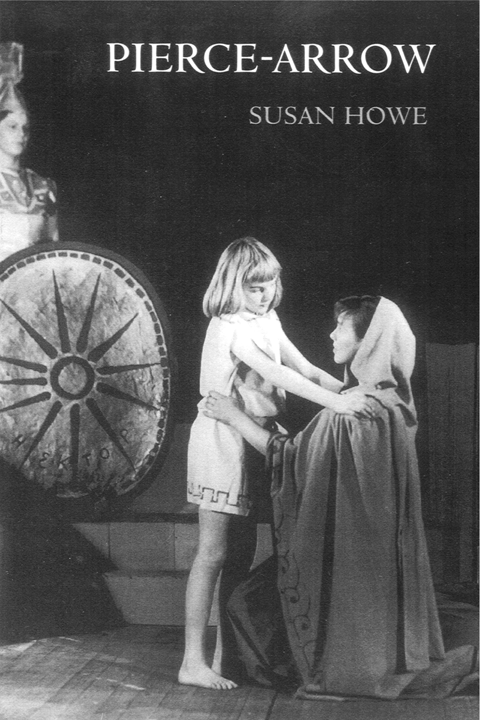

The black-and-white photograph of a young blonde girl with a shoulder-length pageboy hairdo, wearing a toga. The photo is not actually black and white, but rather a study in grays brightened by a black backing or a white detail. Here it is a warm—nearly brown—gray pebbled with darker graphite, and there pale steel clouded with ivory. In folds and yokes of the girl’s clothing, and the clothing of the others shown with her, various matte mid-grays cue us to see red, blue, or green. Only at the composition’s center, where a gleam from below lights up the girl’s hair and bodice, is there a true pearly white.

What else? A Xerox-shaped rectangle, a photo offset or photocopy of a microfiche strip, the rectangle bordered black and centered on one thick ivory page of a book of published verse. Within the gray rectangle separate words (praises, thunders, kills) are repeated according to some pattern, with discrete words enclosed in thick lozenges of border.

A fraying square of white silk from the wedding dress of a Connecticut minister’s wife. The image of a man, walking abstractedly, random pieces of paper pinned to his coat. He wrote on every inch of paper he could find and then came home to his wife, after days of hard riding, with his coat covered in scraps.

Can words composed in holy awe betrothe him to Christ, marry his sin to redeeming graceful love? He prays it might be so, for his tradition tells him the Word is a wedding garment. Along with his wife’s wedding garment, some of his scraps may still repose in drawers in Yale’s Sterling and Beinecke libraries.

Such delicate and perishable objects, their structures resolving to nonstructure, or nonstructures to structure, are central in Susan Howe’s poetics.1

Typically, these objects to which Howe gives a nearly ritual power are ones she has personally salvaged and then subjected to a unique process of composition. Trained originally in the visual arts, Howe makes poetry (rather than merely writing it) as painters make art. From the personal libraries and scrapbooks of her own parents and forebears, from local libraries in small Massachusetts, Connecticut, Berkshire, and Adirondack towns, and from the great institutional archives where books deemed worthy of keeping reside—Harvard’s Houghton and Yale’s Beinecke—Howe retrieves the articulate textual remnants of her New England past. Later, at home at her table, sitting near a window that brings in light broken by tree shadows, she coaxes these objects into second growth. She exposes their surfaces to the changing light on her desktop and then the technological light of the photocopier. After she has copies in hand, she begins the delicate grafting and quilting operations that give her pages loft and texture, and even a sort of grade, and she also composes the meditative or lyrical stanzas closest, in traditional terms, to what we call poetry.

Legibility, transparency, and even navigability are aspects, but hardly the most salient, of her poetry’s features. How could they be, in this poetry so many featured, this poetry ambitious of exceeding, while including and honoring lyric form?

By and large, English readers expect that poems shall express the personality of an individual self, a self for whom the lyric “I” is spokesperson and whose subjectivity is represented by the supposed transparency of print. Poetic success, in the traditional model, is achieved best when the set of highly dense and quite material conventions, the poetic apparatus, can be made to seem sheer. For the extent to which print can be a communicative medium depends upon the individual voice that confers beauty by washing the world with vision, leaving it glistening. Traditional books of poetry will, in fact, contain any amount of obscure printed matter, but all such matter will be suspended within the life-giving fluidity of the lyric voice that contains and masters them. “Readings” are generally expected to enhance this experience of absorption, translating poetry on the page into sounds whose referential rather than acoustic or musical qualities will pierce the intervening crowded space of the room full of chairs, persons, microphones, and hearing aids.2 One hears a poem at a “reading,” or reads a poem in one’s own mind, but the poem, we presume, is not altered. Only the delivery system is different.

Moreover, in America, poetry is often justified, if at all, only for its capacity to elevate us morally, to offer edification or moral improvement. It is expected that, as the poet aims his work at producing insight, his reader travels via printed lines on a journey whose end will be his own deeper understanding. As the popularity of explicit hortatory themes withered in America, it nevertheless remained a given that poetry and philosophy were hortatory forms. For instance, readers accepting that an arrangement of lines need not mimic a “psalm,” that lines need not scan or count off in numbered stanzas to earn the right to be called poems, still wanted their poems to end with a redemptive bang. Readers assumed that the lines of a poem would conduce toward growing clarity, its progress initiated from the left and going to the righthand margin of a single page. Development on the page, in other words, would mimic growth or revelations within the psyche or soul of the reader, with destiny of poet and soul joined. The traditional poem ministers to this destiny.

What makes the poetry of Susan Howe so different is that the poem is not a minister or medium of transparency. The poet does not stand outside. She is, often at much risk, vulnerability, and exposure to herself, inside the poem, her voice one tactile, historical object among other objects in the poem. Her quest for the beautiful poem is not for what frames or contains. If the lyric speaker is usually outside her book, her “voice” containing the poem’s contents, here the lyric voice sounds from within, and lyric consciousness has no special privileges.

If the book is to be opened

I must open it to open it

I must go get it if I am to

go get it I must walk if I

walk I must stand if I am

to stand I must rise if I am

to rise I had better put my

my foot down here is where

consciousness grows dim3

Howe shows in such lines that poems have a weight and volume, palpabilities and opacities running counter to trained expectations. Though her poems can be called experimental and seem, on first glance, radical, this Connecticut poet is a secret sharer dwelling in the neighborhood of Wallace Stevens, who wrote that “the greatest poverty is not to live in a physical world.”4 As in Stevens, so in Howe. Not only is it axiomatic, in Howe, that the greatest poverty is not to live in a physical world but also that the physical world is historical. Such convictions have implications. To journey into the literary past is not, and will never be, for Howe, a matter of mere exercise of mind. The intellectual life of the poet will need more than clarity of vision, will be held accountable to disciplines more palpable than the cerebral ones—to farming, quarrying, harvesting; to the work of pioneer wives packing and unpacking, storing and arranging; even to uncomplaining attendance in a Hartford office. Even when the tools she uses are electronic—and she does use them—the most dematerialized of processes will retain its tactile feel or else lose purchase on the beauty of the objects it seeks. Even a Google search does, for Howe, retain the palpable labor intensiveness of mining or agriculture or an arduous handicraft.

It is no surprise, then, that Howe lets us see the process of making poems as painstaking, even excruciating. The poet’s greedy raid on the archive will always uncover more of the disintegrating paper mobiles, each lovely in its way, than can ever be represented adequately. There is a certain pathos attached to work of this kind, for there will always be a fatter pile of photocopies, a taller haystack of the lovely mobiles, than any publisher will ever include in a book, always the prospect of diminishing returns for labor expended. Sometimes one feels how charily Howe has set down words, feels a Frostian thrift implicit in Howe’s craft of honoring diminished things. And sometimes one senses, conversely, a certain luxuriousness in the enterprise, so lavishly deliberate, even prodigal.

Which fossil-like sprays of print, some black and distinct, some blurred and eroded, will find a place within the area of Howe’s page? How to “frame” these? Shall the simple window-sized rectangle of a single page best frame the scrap or image, or ought the scrap instead form, say, part of a diptych, conversant with its facing page? If part of a diptych, shall the shard or flake be shadow, or herald announcing, or its coeval, and, if so, shall it appear in line with or raised above or below? Should the font or typeface be as distinct, more distinct, or less distinct than that on its facing page?

What of the rhymes or patternings, the principles of coagulation and scattering, that unify or loosen the pages? Shall there be threads of theme carrying through an actual narrative story line, or shall images pool in coagulant interknit structures—verbless, objectless, and yet visually or sonically dense? To what extent shall individual words comment on, reflect each other through sonic imitations or visual punning, and to what extent shall the individual line, or even the grammatical sentence, frame a given stretch or movement of the poem? When, and with how much information, shall the poet offer teacherly exposition; when should she narrate in a twenty-first-century plain style what she experienced when she wrote the poem? How much weight should she give to such passages?

What about the physical book as it organizes and is itself altered by an interval of reading? Books are read, Howe lets us see, by sunlight or lamplight, on divans or in bed or at library tables, for work or diversion. What about the weight or importance of any one page within the mobile architecture of the book itself? Pages may be flat, but books are made of 180 degrees; every page traces the arc from O degrees to 180 every minute or so. As the page turns, the reader’s fingertip active, the geometries of relation between eye and print alter. Light dawns or spreads its bloom out from the spine of the book to the edge and then light is sucked back into the thin crevice. We block it out, but each page we press to 180 flat narrows back to nothing before it reopens. Reading constantly hazards triangles as well as rectangles. Only when we fail to open a book fully enough on the photocopier are we reminded of the way print slides on the diagonal down into a closed book, the inner margin an angled slope into the dark spine.

The mobile sculpture of the book is, what’s more, a technology encased by and dwelling in the more complex architecture of the library. Houghton Library at Harvard, no less than Mt. Vision in the Berkshires, is a complex site, creviced and craggy and promontoried. Nature and culture are interleafed and mingled to a far greater degree than we admit. Howe shows how certain “natural” spots on the North American crust—tracts of Adirondack acres where Protestants met Indians in war, for instance, or the Cape Cod coast, or certain becalmed Pennsylvania foothills where religious pilgrims preserved extreme cultural quietus—are textually fecund, full of articulate sounds, and sedimented with printed matter the poet can detect and carry into the future. Conversely, she disallows merely mental or intellectual spaces. Libraries, and especially the great ones like Houghton and Beinecke, are features of an environment composed out of material indigenous and transplanted, made by persons native or migrant, of stone and wood, their door frames and elevator shafts constructed once and forever changing, though less perceptibly. In banks of oak shelving on slate floors, in their cooling systems and Dewey decimal systems and maps, these buildings have declivities and broad plateaus, accessible pathways and unnavigable outcroppings, which, like a mountain or body of water, facilitate or impede, filter or speed engagement with their contents.5 Like Keats who, in reading Chapman’s Homer, compared it to the enlarged vistas “stout Cortez” beheld as he stood “Upon a Peak in Darien,”6 Howe stands upon her peak in Beinecke Library and surveys the American canon.

Susan Howe has written far more books than can be explicated here, and so I shall confine myself to looking at the last four, two from the 1990s and two from the early twenty-first century. These books will serve to represent Howe’s mature work. Singularities (1990) and Pierce-Arrow (1999); the small, privately published Kidnapped (2002); and, finally, Souls of the Labadie Tract (2007) allow us to watch Howe’s mature techniques in motion and development. I shall concentrate on describing the poet’s relationship to precursors and history in the volumes Singularities and Pierce-Arrow, and, more concisely, in Kidnapped, before going on to analysis of Howe’s most recent work, Souls of the Labadie Tract. There the poet becomes the courier between two Connecticut forbears, Wallace Stevens and Jonathan Edwards, making her own verse conversant with theirs.

Along with her colleagues of the L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E school, and in the tradition of William Carlos Williams, Howe’s work has not only questioned the associated ideas of lyric subjectivity and self-possessive, self-assertive individualism but has also traced both to certain aggressive syndromes of the Puritan mind. This given, Howe has also cherished Protestant thought and, especially in the traditions of Protestant literacy, has created an aesthetic field with semaphores up, attuned to beauty and prolific in producing it.

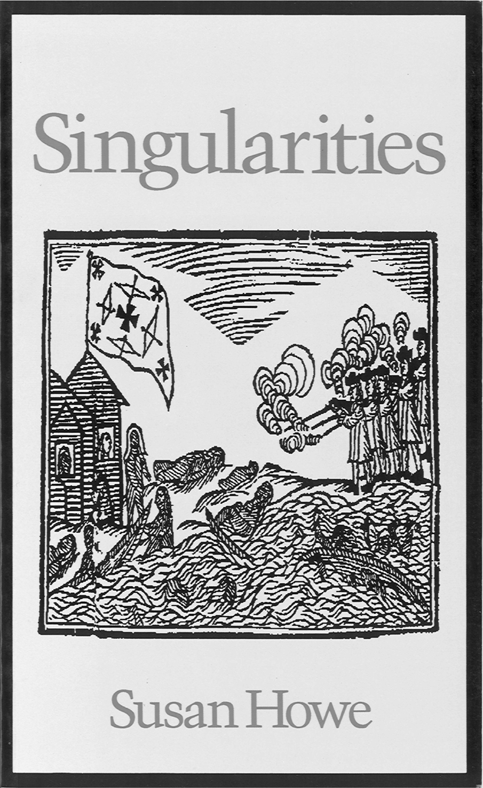

Illustrating this point is the cover of Howe’s Singularities, a cover that does not just illustrate but initiates and inaugurates the reading process. Tinted an antique powder-puff pink, the book’s cover typifies books as decorative elements that furnished refinement as they “civilized” and domesticated the wilderness. Meanwhile, the cover’s woodcut illustration tells a more violent story. The woodcut depicts a phalanx of black-hatted marksmen taking aim across what seems either a rolling sea or a planted field—in either case, someone is dying or drowning in the billows. Ambiguity also surrounds what lies between the shooters and their targets: sheaves, women, swaddled babies, or merely compacted leaves. Are the shooters in the woodcut perhaps uniformed British soldiers aiming at colonials in woodland settlements or, perhaps, colonials taking aim at Indians in longhouses? Battlefield and planted field share the same outlines, suggesting agriculture’s slow-growth aggression, while the stylized foreshortened compression of the battles between whites and Indians, particularly those taking place around Deerfield at the commencement of King Phillip’s war, suggests a telescoping of many battles and of history itself as battlefield. The woodcut seems (in the manner of Williams’s prologue to In the American Grain) to expose the fear of contact, to represent the cold blossom of pride that allowed Americans to treat the earth as—in Williams’s words—“excrement of some sky.”7

European trashing of the American wilderness, a despoiling as old as the first Europeans’ arrival but renewed in every century, is a theme Howe develops, especially in the second long poem of the volume, “Thorow.” There Henry David Thoreau’s alienation from the despoiling of America by commerce prefigures her own alienation before the cheap motels and gimcrackery of modern day Lake George. Again one hears echoes of Williams, as Howe finds that the “pure products of America go crazy.”8 The very entering of the wilderness and settling it is a form of madness that wreaks vengeance on the land itself, turning it to ugliness for the sake of private possession and discreteness of soul. This does not mean, however, that the poet marooned by Lake George, living out a winter in cold winds next to glittering ice, denies sympathy with the volume’s central perpetrator-victim, the seventeenth-century minister Hope Atherton who, lost in the woods during King Phillip’s war, was finally set aflame and ran to his death. Howe lets Atherton’s purity of belief, his naked fear, his Protestant aloneness abide within and ignite her own lyricism. Through Atherton’s stiff but lovely archaisms, Atherton’s genuine if myopic convictions, his chilled and threatened accents, Howe finds a certain redemptive womanliness in Puritan clerical speech. Also, Atherton’s womanish name, Hope, softens the barriers of time and alienation so that the poet, in effect, takes him in. Howe, the lonely poet holed up in the frozen woods, is no stranger herself to defensiveness, to wondering who is her enemy and who her friend.9 It is a milder version of wilderness panic she experiences during her sabbatical in the Mohawk wilderness, but she too fears marauders and girds herself defensively. She too suffers the syndromes of individualism, spasms of singularity.10

Figure 12.1. Cover image of Susan Howe, Singularities (Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 1990), copyright © 1990 by Susan Howe. Reprinted by permission of Wesleyan University Press.

This “singularity” is at least part of the problem. Hence the plural title of the volume, Singularities, a title that deexceptionalizes while it also takes names and apportions accountability. Singularities gives the lie to the Puritan settler’s assertions of chosenness, it exposes the modern advertiser’s exploitation of the niche and it endeavors to find a place of kinship between the two aggressive proponents of chosenness, the Reverend Hope Atherton and his later-day nemesis, the woodland sojourner, Henry David Thoreau. To both of these, and channeling the communicative Whitman as well (for Whitman, as Christopher Looby notes, is interleafed with Howe’s verse, as all poets, and persons, are tucked into his Leaves), the poet declares:

You are of me & I of you, I cannot tell

Where you leave off and I begin

(58)

This relationality is crucial to the volume and to historical understanding as Howe seeks it. Historical consciousness is a remedy for excesses of singularity and a means of entering and sympathizing across lines of estrangement or aggression. It teaches us that we are interleafed, softens the distinctions of persons according to and along coordinates of proper identity, historical epoch, language, and compass points: Hope Atherton, a seventeenth-century English speaker living in western Massachusetts, is usually held distinct from Henry David Thoreau, a nineteenth-century English speaker living in eastern Massachusetts, who is ordinarily held distinct from Susan Howe, a twentieth-century English speaker living in southern New England. But these distinctions are nullified by language, which connects us all.

Only the most meager, most nonhistorical, uses of language, Howe shows, will confine themselves to expressions of a placed and mortal subjectivity—a person of one time and place. Poetry’s richer capacities, its more elastic talents, may be used to achieve the resonant scattering, to help us hear sound forms that persist across spaces unbound by occasion. Indeed, the only kind of verse one hardly ever finds in Susan Howe is the “occasional.” Rather, the single, double, and multiple panes of paper surface offered by a printed book are like springboards and landing spaces. The pages of a book entertain the commerce of syllables and nomenclatures. A page is where idioms and linguistic changes still in process leave their prints.

Howe’s refusal of lyric singularity in favor of the space of the book may eschew the privileges of the individual, but it is anything but impersonal. As she carries Hope Atherton’s pitiable, poignant singularity, she carries, too, that of her lyric forbears whose conventions of authorial power and forward thrust are her historical inheritance: “Work penetrated by the edge of author, traverses multiplicities, light letters exploding apprehension suppose when individual hearing” (41). But, beyond this, Howe’s emotional, even plangent tonal register reminds us that writing does not slake but extends need; writing consists in a disarmed exposure of the writer’s mind, psyche, and heart to the unknown. The seignorial distance and cutting frontage of authorship is always, happily, subject to ambush by reading, which turns the self into a throughway, a way of admitting the dead to take up habitation within one. Reading opens the book of the self to other leaves, which then dwell somewhere therein, their force liable to discharge at any moment.

Thus the fascination with “Thorow,” Howe’s scout and guide, in Singularities. During her visiting professorship at an upstate university in winter, the poet finds not Thoreau but “Thorow.” Thorow clears trails, we might say, within the imagination of Susan Howe, who becomes disidentified with her “self” just as “Thorow,” spelled with an English rather than French set of ending vowels, is disidentified from his. Not identical with his name, Thor-row is now, as one correspondent puns, a god-like “Thor” who “rows” (down the Concord and Merrimack). Not only does Thoreau row, but he rows on eau. Indian place names end with the suffix et and his ends with eau—both are words for water. Whatever the biographical personality Thoreau had, “Thorow” has riverine fluency and ready translatability; his name, like “Hope” Atherton, becomes not a singular label but a place of passage, a sort of pump. With “Thorow” at her back, the poet barricaded in her cabin ventures out, moves into “the weather’s fluctuation”; she gets the Indian names “‘straightened,’” by which she means “more crooked.” Now she may read American history differently, allowing the language of one epoch to wash over that of another, admitting the past to the present.

A sequence of examples will demonstrate how this all plays out within the volume. The setting is northern New York, mid–twentieth century, the Adirondacks, where a poet, sometimes lonely, lives in a primitive cabin through a cold winter. Indian wars were fought in this place, as they were along the wide belt of the Mohawk lands extending east to Concord. And so the poet, through the winter, keeps the Reverend Hope Atherton, who fled from Indians through the woods, and the naturalist Henry David Thoreau, in mind. The battles between whites and Indians, part of the archaic American experience, are yet more archaic, these conflicts now including the whole American continent and the epic history of war and terror. Howe endeavors to represent—all at once—the regular cycles of snow on earth, centuries of English and Indian habitation, fluctuations of fear, anger, and reverence. The ancient clash of bloodied arms achieves lucidity when, in Hope Atherton’s “voice,” it records:

Loving Friends and Kindred:—

When I look back

So short in charity and good works

We are a small remnant

of signal escapes wonderful in themselves

(16)

Yet Atherton’s lucidity is achieved at the cost of much ambient depth of echo and many other sounds—of Indians, of woods, of seasons flowing through. It is as though the poet restricted language to the narrowest chamber to leave it in the care of the subjective voice. Thus, Howe lets the sound scatter, retrains it not only through the singular consciousness of a man’s particular event, Hope Atherton’s, into a larger surround, bouncing and rebounding off his cherished books and his dreams of Atlantic passage, his still-and-never-to-be unlearned Continental and filial humility, the slow occlusion of European memories by New World flora and fauna, and these off each other, since sounds compose their own relations.

Otherworld light into fable

Best plays are secret plays

______

Mylord have maize meadow

Have Capes Mylord to dim

Barley Sion beaver Totem

W’ld bivouac by vineyard

Eagle aureole elses thend

(11)

Atherton’s humility before old forms of authority, his instinctual awe before the dazzle of New World heights and expanses, his natural reaching for biblical vocabulary to express exaltation, all these are compressed in these lines, the echo between worlds giving rise to a music no more crowded than history is. Obscurities in Howe are rarely opaque, although they may be refractory. What is “thend”? Perhaps it is “the end” subjected to the rules that allow “would” to be represented as “w’ld.” Or something else—the thrumming sound, perhaps, of that eagle’s wing, the concentric inexactitude of the eagle aureole sharpened, sleeked by the d to a feathered edge. That d cinches rhymes that wavered in one line; read down the strophe’s edge and you will find that, as dim is to vineyard, totem is to thend.

A few more pages and more radical crosscuttings and interleafings break the integrity and decorum of the page. The poem itself becomes a tool of crosscutting, a chisel releasing the plural singularities that populate false singularities. A vertical oblong of couplets, with white ribbons of double space between each and a theme of “marching,” give page 12 a forward leaning, epic-feeling surge across the gutter and between the leaves, impossible to ignore. Instead of ribboned lines, words not yet given semantic purpose, words not yet phalanxed or devoted to a cause, are arrayed in their native spirits—“Nature without check with original energy,” as Whitman had it.11 “Epithets young in a box” (13), the poet calls these syllables, these hard sounds unused to use, electric and many edged. Brilliant tessellated puzzle pieces milling in a square without the protocols of right to left to define their order, these words regain the density of epithets. Pictographic diagonals have just as much charge or more than laterals. Hence

architect

euclidean curtail

(13)

Or

a

severity whey crayon

(13)

Or

shad sac stone

recess

(13)

These little chimnied or cellared sheds of sound do not refuse all denotative gestures. They conjure, for instance, the actual phenomena in a primitive world (human settlement staked out through geometry, the oblong whey squiggles of loose bowels, a lovely sunlit pond incubating aquatic life), but their visual and aural shapes, stacked or leaning pyramids of c’s and s’s, latinate clusters starting back in the palate, have an interknitness of their own.

In Singularities the poet who was a visual artist has much to teach us about how forms confer beauty on other forms simply through patterns of resemblance and variation. For once, as she shows, thor ow (or eau) bursts the bounds of the singular person, once poetry leaps the fences of the lateral and the boundaries of the page, then, with the up-and-down joists of the book loosened, new species of poetic gravity, accountability, and kinship may descend. Once it is no longer human consciousness, with the lyric speaker in loge (lofted above, driving thought left to right in obedience to intention, past to future from nascency to destiny), words and thought may be seen in their more natural state. They splay and spread like lichen growth or tree fall, half living, half dead, turned face up, face down, some above and some below ground. From inside language’s thicket, voices—even the poet’s own voice—may be heard.

Choral, transtemporal, chthonic, language is beautifully crooked, branching and unlinear, turned and turned by tropings, cognitions, and recognitions.

That persons can never be transparent; that poetic “speakers,” like philosophical “thinkers,” are only by the most extreme suspension of disbelief reckoned to master, guide, or control materials; that there are other offices for the poet than Cartesian reflection or—even in America!—rhetorical (national) or homiletic (religious) persuasion—such convictions of poetry’s coextensive relation with matter and complex ethical action inform Pierce-Arrow and Kidnapped, both of which highlight the poet’s role as actor, reactor, and accountable ethical subject rather than pure supervisory will. Indeed, as Stephanie Sandler has noted, the accountability of Americans, including intellectuals and the institutions organizing intellectuals, to the exertions and dispositions of American power is a topic vital to Howe.12 We have seen this in her treatment of scenes of war in Singularities. The idealized transparency or transcendent quality of the intellectual life are, as Howe shows in Pierce-Arrow, belied by how intellectual careers actually play out, with the levers and gears, the individual career trajectories and high stakes power struggles of university life mimicking those less idealized. A career within the “ivory tower” is, as Howe reminds, a trade like any other, where ideas may be pressed into service as tools and the growth or stasis of disciplines liberated or impeded by demands of ego. And, of course, competition between disciplines, like the age-old contest between poetry and philosophy, deprives both of claims to any transcendent poise and restores them to history.

Poetry itself, these books remind, is a production, a profession, an institution. Thus Pierce-Arrow, largely set in the academy (art’s patron and paymaster), finds Howe reflecting, as she had in other volumes, on the boundaries, constraints, and strictures governing creative life in New England’s capitals of intellect.13 Howe is not shy about allowing the tension between and among members of the intelligentsia to enter her poetics. Not for nothing does she, riffing on Thorstein Veblen, title the second part of Pierce-Arrow “The Leisure of the Theory Classes,” as not for nothing had she given over pages of her work The Birth-Mark to exhuming and working through her own memories of Cambridge, Massachusetts in the 1950s. There, as daughter of a law school professor and an Irish actress, she came of age amid the posturing, genius, and tipsy grab-ass of the cold war academy.14 Not unambivalent, but also not dismissive of her own opportunities, Howe makes her poems reflect the experience of one born into not only her own life but into a way of life. Like Mather and Eliot children, Holmes and Lowell and James children—privileged for being what is called, in academic parlance, “legacies”—Howe, daughter of a Harvard law professor, is informed by the name she bears and forever marked by the grid of Cambridge streets. To have come of age as a daughter of American law and the Irish stage, to be the sister of a poet and also an actor, are not incidental attributes but conditioning facts that Howe makes use of in her poetry. The fraught, if often fruitful, tensions between creative temperaments and the bureaucracies that pay their livelihoods; the national, ideological, and religious imperatives or fashions that may elevate one strain of thought over another; the inverse or torqued relation of genius to success; the sharp byplay between intellectual centers and hinterlands; the ups and downs and variances within and between intellectual careers; and, finally—of a salience nearly impossible to exaggerate—the kinship customs and rituals of bequest, the protocols of transmission, inheritance, and memory that enable or interrupt the flow of ideas across time—to all these Howe opens her verse. A true New England native and student of its intellectual and poetic history, Howe appears in her verse as just that, representing the interimplicated history of intellectual life, poetry, and the professoriat.

Thoughout her career, Howe has mapped with great precision the consequential descent of American poetry, like American philosophy, from American theology. Indeed, Howe has reckoned more precisely than any other contemporary poet the exquisite trade-offs and paradoxes of such an inheritance. “God’s Altar needs not our polishing.” Thus Cotton Mather had once inveighed against Anglo-Catholic aestheticizations, while Jonathan Edwards, of the same Calvinist tradition and a key figure for Howe, saw in “the beauty of the world” the Divine maker’s Hand. Either way, the Calvinist-Cartesian regime required poetry’s justification to be found outside the realm of art, its office outside the purely aesthetic. Ideally, poetry was countenanced as a device for producing inspiration, whether national or religious or both. Or, elevated language was to be a medium of praise and glorification, a means and mechanism of revelation, or a help toward godly conduct.

“From 1860 on in nineteenth / century American colleges / philosophy was an apology / for Protestant Christianity,” writes Howe in Pierce-Arrow.15 A little later she quotes Charles Sanders Peirce admitting, “One of my earliest recollections was hearing Emerson deliver his address on ‘Nature’ and I think on that same day Longfellow’s ‘Psalm of Life’” (116). In these quotations we see that not only are poetry’s and philosophy’s hereditary American duties fulfilled, their manifold accountabilities to standards ethical and improving summed up, but also their tutelary function is carried out, one institutionally insured. The great institutions of culture that provide Howe her key mise-en-scènes do not leave disciplines to their own devices. At Harvard and Yale the homiletic imperative is never far off.

Half of the company

would try to portray

some abstract quality

Fear Courage Ambition

Love Conceit Hypocrisy

(72)

In Pierce-Arrow, a poem with Charles Sanders Peirce at its center, Howe finds numerous ways to give density to the persons and forms of academic instruction, using the transgressive, brilliant antihero Peirce as avatar of this density. Peirce’s most lasting contribution as philosopher may have been to prove the irrelevance, to question the existence, of such abstract qualities when estranged from practice. The mere idea of instruction—the transmission of mental matter via and through the institution of the professoriat (an idea parallel, in Howe’s understanding, to poetry as a transparent medium for the conveyance of feeling or beauty)—was one Peirce doubted and dismissed, that vocal dismissal doubtless compromising and eventually dooming his claim to an office of “instruction” at a university. As Howe mordantly informs, Peirce regarded the notion of the university as “institution for instruction … grievously mistaken” (7). She lets Peirce’s companion, Juliet, define his more intimate relation to ideas: “He loved logic” (1). Of course Peirce’s own lifestyle, in particular his relationship with Juliet, a woman not his wife, made him notorious and lost him several academic posts, but Howe focuses more on the scandal of Peirce’s pragmatism. To “love logic” in this sense is a classic, pre-Socratic activity in which things are as they appear. For Peirce, the activity of pursuing the logical across a page of paper is an enterprise of the “passion-self” as edged and decisive as any march of epic warriors.

Each assertion must maintain its icon

(3)

As she develops her complex meditation on Peirce, a poem doubling as her own elegy to the departed husband, David, Howe gathers in a larger community of departed singers and thinker-lovers, communicants of Peirce and David. Howe herself writes that such poems as “The Triumph of Life” and “A Leave-Taking” comforted her during years of loneliness in Buffalo, Swinburne’s loverlike fluency and plangent ripplings recalling her husband’s skill at the tiller. George Meredith, and Swinburne, Peirce’s late-nineteenth-century contemporaries, function in the book as his adjutants and secret sharers, all three blessed with a pleading that does not efface itself. Meredith is revealed through various personal effects, pens, pencils, and a period silhouette fashioned by Sir John Butcher, Swinburne through his desk and the discarded, much-edited, unfinished manuscripts he left. All three men are examples of unmetaphysical, untranscendent forms of immortality, as her husband’s art—sculpture—exemplifies the idea persistent in material form. The poetic work does not transcend, does not “pierce” (Howe plays on Peirce’s name here) or find some metaphysical persistence outside its physical form. But, in some essential way, as Peirce’s philosophy remains immanent, secreted or “pursed” within the vascular tissue of the manuscripts, within the expectant point of the pen, within the storehouse of the archive, so does Howe’s poem. If conventional notions of poetic immortality make it depend upon transcendence of print, paper, and ink, these are turned on their head. In Pierce-Arrow the arrow that would pierce is revealed as a purse, love still moist within. For it is, in the end, the great ardor of Peirce (for language, for his aptly named Juliet) that is expressed and reciprocated. Poetry itself, Howe shows, is inevitably an act of love.

The holder of such a view as Howe’s will necessarily submit to wearing her own heart on her sleeve. The book, dedicated to the poet’s late husband, the sculptor David von Schlegell, has Howe wearing herself on the cover and the back flap. Specifically, on the front we see a photograph of the young Howe in 1947 in a Cambridge, Massachusetts performance of The Trojan Woman, while the back flap shows her, in sunglasses, in front of the remains of the Pierce-Arrow automobile factory in Buffalo, New York, the struggling rust belt city where Howe taught until her retirement in 2008.

Figure 12.1. Cover image of Susan Howe, Pierce-Arrow (New York: Directions, 1999) copyright © 1990 by Susan Howe. Reprinted by permission of New Directions.

This book of poetry, written between childhood and adulthood, Cambridge and Buffalo, is her vehicle too. The poet does not deny that as a writer of poems she plays a dramatic, a performative role, one among others in a lifetime of roles. This book, Pierce-Arrow, traces a poignant trajectory, that of the poet’s own growth. The tender curve of the maturational arc—the arc of a girl’s growth in and through forms of art, in and through stages of love—the nakedness and guardedness of the artist, the nakedness and guardedness of the woman—these themes lend a terrible tenderness to Pierce-Arrow. Liaisons with books and encounters with lovers share vectors. Both human and intellectual love aim dead at the heart.

As a younger poet, and one associating with the poets of the School of Poetry and Criticism at SUNY, Buffalo, Robert Creeley, and Charles Bernstein, and as a member of the loose confederation known as L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E, Howe has, throughout her career, engaged in a certain amount of quiet polemicizing against the expectation that poetry should be weightless. Given the separation of the critical and the creative that has evolved in universities, the way Howe sends criticism to the school of poetic craft has put her, along with others, in a position of opposition. She found a kinswoman in Emily Dickinson (My Emily Dickinson), plus an alter ego in the Indian captive, Mary Rowlandson, and she has found foils and also valued interlocutors in such scions of the academy as Perry Miller and Helen Vendler.

Miller, author of The New England Mind: The Seventeenth Century, treated Americans as Augustinean agonists, lonely churches of one (in Niebuhr’s phrase), and he dematerialized the Puritan inheritance by turning New England history into a history of ideas.16

Helen Vendler, the twentieth century’s most celebrated defender of the subjective lyric, has argued for forty years in favor of the individual agency and necessary boundedness of a poem. Poems are, Vendler eloquently argues, what “soul says,” the particular textural and thematic signature of a poet’s style confirming and affirming the unique texture of the individual.17

Not so, Howe’s stylistic crossweave demonstrates. Universities, intellectual communities, the professoriat, are not merely the settings in which minds operate, providing rooms for them to train limpid vision on objets d’art. Universities with their libraries and offices, their copiers and faxes, their sprawling neighborhoods of rental housing and substantial real estate, and not least their demographic instability and their transatlantic traffic, are part of the texture, entering the pure realm of ideas. Was America ever really America, its soul ever its own, Howe asks, when Boston rips off London? Nor is Harvard Harvard, nor Yale Yale, when Yale makes itself not-Harvard, Harvard makes itself not-Cambridge, Henry makes himself not-William or precisely William. National identities, like personal ones, are all so much annexation and occupation, so much ransoming, you kidnapping me, me you, every poet made out of her sisters and her uncles, volume after volume of imitation and theft down the years.18

Kidnapped demonstrates. In her first book of the twenty-first century, published in a limited edition of three hundred, Howe rewrites the American story of migration with materials from her own mother’s family archive. In Howe’s hands, the Manning family’s journey to that most quintessentially American place, Massachusetts, is no Milleresque errand into the wilderness, no pilgrimage of individuals yearning for solitary redemption on the North American strand. The Manning immigration is best seen as a set of performances, of plays by a family of traveling actors. What is a family but a set of players? We feed each other lines. What are poets but estranged kin, kidnappers of the word?

Such scatterings and reunions of kin are themes that continue into Howe’s most recent book, Souls of the Labadie Tract. The volume is her simplest to navigate and, in many ways, her most beautiful; it may provide a good starting place for readers who are wary of postmodern experimentalism, but lovers, as Howe is, of Wallace Stevens and Jonathan Edwards. As Kidnapped traced back along the branches of Howe’s own family tree to Irish poets and playwrights, the title poem of this book traces Wallace Stevens to the Pennsylvania lands of his sectarian forbears, thus allowing Howe to press into new tracts of Anglo-Protestant America. The central poem in the book, “118 Westerly Terrace,” ties Stevens to Jonathan Edwards, and both to Howe herself. Imagine the book as a group portrait of three Connecticut poets sharing one ecstatic linguistic raiment and you have its central conceit.

I mean the image literally, for in this book Stevens and Edwards and Howe herself are literally dressed in verse and, too, in the formalized apostrophes of poetry. The language of address, the elevated discourse—whether of poetry or theology or America’s characteristic fusion of the two—adorns the history of Connecticut as a bridal gown adorns a bride.

Both Edwards and Stevens had the kind of intimate physical relationship with the poetic word Howe cherishes, which she credits in part to having learned from them. Edwards rode into the Connecticut hills with scraps of paper pinned to his coat, so that he came back from rides in the hills white-garbed, papered with godly sayings. Edwards’s notebooks and miscellanies, collected at Yale, are still in the process of being finished, since pages of his thoughts from the 1740s are still being puzzled out and transferred into the modern form of a scholarly edition. Where does his real “writing” therefore abide? Stevens, whose ramblings in the envoi to “118 Westerly Terrace” Howe evocatively called his daily “Errand,”19 also had a peripatetic and distributed habit of composition. Thoughts that occurred to him on his walks back and forth to the Hartford Insurance Company where he worked were recorded on “two by four inch scraps” (73), which he would then give to the secretaries in his office to transcribe onto 8 1/2 x 11 sheets. The transcribed scraps then became grist for Stevens’s nighttime and weekend bouts of composition, when he “transformed the confusion of these typed up ‘miscellanies’ into poems” (73).

Although Stevens’s poems have a monumental solidity that belies a liveness and quickness Howe rediscovers in their history, she uses the poem to follow this emergence of the poem “qua” from its many scattered incidents of cohering existence. Where and when does the poem acquire its “is,” its thereness or address? At 118 Westerly Terrace? What then of the walks, where the ideas first emerged, or the office where they became print through the ministrations of stenographers? Or, at Howe’s desk where, reading them, she also writes them? What is the poem’s spatial and temporal address—the manuscript, the printed book? What of the house where the poem was written or the countryside around and about that touched the poet’s mind? Are these some of its genuine addresses? Do these addresses still speak, some speaking to us in tones soliciting response? Might not, for instance, the feeling that we “love” a poem or a poet, or can see the scene it depicts, or, even more obscurely, feel “moved” by its language, confirm the existence of still active address from these other sites?

Such questions established, the book’s sections seem to guide the reader toward the wedding of poet and landscape, matter and mind, present and past, theology and poetry that Howe has always endeavored to represent. The pages of Souls of the Labadie Tract amount to a lovely fusion or wedding of adhesive media, percept, thought, printed word yearning and straining toward each other. And the book’s final poem, “Fragment of the Wedding Dress of Sarah Pierpont Edwards,” appears in various guises. We see it literally, in the title of the book’s final poem, and in a ghostly gray photocopy, a postage-stamp-sized square showing a thready edge of Sarah Pierpont’s actual dress.

And then appears a set of lacelike, pressed, delicate catalog entries on the Edwards family. In the compost of book pressed on book, ripened by time, this detritus quickens into new delicate life. As Williams might have said, they grip down and awaken. These are not merely found objects or bibliographic refuse but a new wild growth, like wild ferns or thistles, sprouting from the page.

Though elliptical, full of gaps, the texture of a Howe poem is not less for being akimbo or tilted on the up-down axis, but more alluring,. An appreciative reader of Howe now knows and comes to crave the tension of letting the eye catch in one of her tactile, bristling installations. There is, in the end, great aesthetic satisfaction in looking through the openwork, the pierced slubby lace of historical knowledge embodied in historical texts. One looks through the fabric as through a veil, the beauty not beneath but abiding in the crush and weave of the historical fabric itself. Nor is this activity simply retinal or visual or aloof. Humane, and good humored toward the lyric speaker, Howe does not exempt herself from the somnambulistic focus, the clenched drive of the rational self, the “workaholic state of revery / Destitute of Benevolence” (85). Burning her candle down, tracing the up and down aspirational phallic linear motions, as if ardor of quest could guarantee success proportional to noise of effort. The poet has a subject self but also suffers; she is relieved to meet her nightgowned forebears.

For a long time I worked

this tallest racketty poem

by light of a single candle

just for fun while it lasted

Now I talk at you to end

of days in tiny affirmative

nods sitting in night attire

(94)

It is a happy thing when the predecessors appear, Edwards or Stevens. To live in a world singly, unidimensionally, is to remain single and lonely when one might lie “happy down the grain.” Everyone in his or her present time—Edwards, Stevens, Howe herself—had to live in a “house-island” (92), inside the shells of the one body, one gender, one historical moment, one house and family. And yet, Howe discovers, literate civilization creates openings for us—thresholds, doors—within the conversant architecture of the stanza. “Stanza” means room, of course. The poetic stanza, unenclosed, is naturally hospitable to poetic converse across time, as in Wallace Stevens’s “rooms.” Walking through them, the poet lets her voice loosen and receive. She utters but is also blessed by apostrophes—“Back to the doorway flow / of life’s energy” (82); “Afternoon at its most glossy / The foyer seems to smile” (92). Every poem, Howe’s own included, is in receipt of inheritances that pass from ancestors, and every poem will become, in time, what Whitman called “nourishment.” Stevens also wrote, in “Postcards from the Volcano,” of children who would never know we were once “quick as foxes on the hill.”20 Poetry brings living and dead to dwell on one plane: “In the house the house is al / l house and each of its authors / passing from room to room” (77). But it also begins to show the present the way into archive and earth, into sedimented rather than singular existence.

Two ages overlap you and

your predecessors—where

they go to where far back

becomes silent and all lie

happy down the brain and

barrier self-surrender for

then all doors are closed

(95)

To see, and to gain help from other poets, to see “what is secret, wild, double and various in the near-at-hand” (74), is what Howe honors Wallace Stevens for giving her in the central poem of the volume, “118 Westerly Terrace.” Time, which laps us together, allows more still to be accomplished of the apparently finished than we think.

What makes us still consider Susan Howe an “experimental” or “avant-garde” poet is our preference for the beauty of authors over the beauty of books. Physical aspects of the poetic volume are still meant, in contemporary habits of reading, to evanesce. We expect that if the poem extends beyond the page, surely other recognizable closing devices will signal its beginnings and ends, edges and centers. We assume that the paper, leather, glue on which thoughts are stored are not part of the poem—that a poem is not a work on paper so much as a work despite paper. Notwithstanding that poems are made of black, clustered, twiggy, looped budwork of print of such impact they swim on our eyelids when we close our eyes; notwithstanding the sound individual pages make as they slip against each other, or the decisive thump they make clapping themselves closed after a session of silent reading; notwithstanding how the hands and the fingers experience, second by second, tactile contrasts between the stiffened leather or cloth or glazed paper cover, which catch and brace the fingers, and the matte or silken page, smoothed to propel them—notwithstanding all this, poems are expected to transcend this embodiment, to present as little distraction as possible to the work of reflection. But the physical density and sensate clamor raised by the objects we use to read poetry can never be set to the side in the poetry of Susan Howe. The beauty of the book is in the book, in its itness and in the itness of the author who, in looking through is also seen in the pane, the lens, on which she leaves her own print.

Face to the window I had

to know what ought to be

accomplished by predecessors

in the same field of labor

because beauty is what is

What is said and what this

it—it in itself insistent is

(97)

Within the true world of what “is,” Howe denies living in a world in which nothing has ever died out. What “is” is never achievable by the singular self, sitting by its rackety candle. This particular book is made of particular materials and relationships, by books that precede every poet’s own book, the dictionaries full of words that precede her words, the libraries in which these books are held. Also of the cloverleafs on the highways spooling toward the libraries, the winter or spring or summer stand of trees growing around the libraries, and the leaves pressed and composted under the trees. And those buried under the trees with the dead.

Notes

1. For other treatments of the material aspects of Susan Howe’s work, see Marjorie Perloff, Radical Artifice: Writing Poetry in the Age of Media (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994), and Twenty-First-Century Modernism: The “New” Poetics (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2002); Susan M. Schultz, “Exaggerated History,” Postmodern Culture 4, no. 2 (January 1994); Stephen Collis, Through Words of Others: Susan Howe and Anarcho-Scholasticism (Victoria, BC: Department of English, University of Victoria, 2006); and Peter Quartermain, Disjunctive Poetics: From Gertrude Stein and Louis Zukofsky to Susan Howe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009). See also Howe’s own Web site at the Electronic Poetry Center (http://www.epc.buffalo.edu/authors/howe) and the site at Penn Sound (http://writing.upenn.edu/pennsound/x/Howe.php). Walter Benn Michaels has argued that the emphasis on the materiality of texts is misguided. See his provocative The Shape of the Signifier (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004).

2. “Transparency” gets a powerful and sustained critique in Charles Bernstein, A Poetics (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1992). See also Marjorie Perloff’s sustained analysis of the value, and limitations, of transparency in Radical Artifice.

3. Susan Howe, Pierce-Arrow (New York: New Directions, 1999), 57. Further page references will be given parenthetically in the text.

4. Wallace Stevens, The Collected Poems of Wallace Stevens (New York: Vintage, 1990), 325.

5. Libraries are crucial spaces for Howe, and the experience of navigating a library as important as any similar experience of navigating through “natural” space. A good place to begin investigations into the material aspects of the American library is Thomas Augst and Wayne Wiegand, eds., Libraries as Agencies of Culture (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2003).

6. John Keats, “On first looking into Chapman’s Homer,” Complete Poems and Selected Letters of John Keats, intro. Edward Hirsch (New York: Modern Library, 2001), 43.

7. William Carlos Williams, The Collected Poems of William Carlos Williams: vol. 1, 1909–1939, ed. A. Walton Litz and Christopher MacGowan (New York: New Directions, 1986), 218.

8. Ibid., 217.

9. Howe’s “autobiographical impulse,” to use Hawthorne’s phrase, complicates her eschewal of lyric subjectivity in interesting ways. Plainspoken scene setting and contextualization of a given poem within Howe’s life and career are as common and persistent as more difficult features of her work. She is a cooperative and quite enlightening interviewee: see Susan Keller, “An Interview with Susan Howe,” Contemporary Literature 36, no. 1 (Spring 1995): 1–34, and Schultz, “Exaggerated History.” Along with Hejinian, Howe is often of interest to critics of women’s autobiography: see Rachel Blau DuPlessis, The Pink Guitar: Writing as Feminist Practice, 2d ed. (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2006), 123–39. Kathy-Ann Tan goes so far as to devote a book-length study to the “Poetics of Autobiography”: The Nonconformist’s Poem: Radical “Poetics of Autobiography” in the Works of Lyn Hejinian, Susan Howe, and Leslie Scalapino (Trier: Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier, 2008).

10. See Peter Nicholls, “Unsettling the Wilderness: Susan Howe and American History,” Contemporary Literature 37, no. 4 (1996): 586–601; Tan, The Nonconformist’s Poem; Collis, Through Words of Others; Ming-Qian Ma, “Poetry as History Revised: Susan Howe’s “Scattering as Behavior Toward Risk,’” American Literary History 6, no. 4 (Winter 1994): 716–37; and, again, Perloff, for treatments of Howe’s materialist approach to history.

11. Walt Whitman, Complete Poetry and Selected Prose, ed. Justin Kaplan (New York: Library of America, 1982), 188.

12. I am grateful to Stephanie Sandler for illuminating conversations on Howe’s work, including several with Howe herself, and for many suggestions that much improved this essay. I am immensely grateful to Susan Howe for an unforgettable afternoon in New Guilford—including the opportunity to see her workspaces, her personal library and beautiful environs—and for her visit to Harvard and reading in the spring of 2009.

13. See Nicholls, “Unsettling the Wilderness”; and Schultz, “Exaggerated History.”

14. Howe’s great attachment to, and ambivalence about, Harvard and the Cambridge of the fifties is most on display in The Birth-Mark: Unsettling the Wilderness in American Literary History (Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 1993).

15. Susan Howe, Pierce-Arrow (New York: New Directions, 1999), 71. Further page references will be given parenthetically within the text.

16. Perry Miller, The New England Mind: The Seventeenth Century (Cambridge: Belknap, 1983).

17. Helen Vendler, Soul Says: On Recent Poetry (Cambridge: Belknap, 1996).

18. On the other hand, Howe is as generous at acknowledging her own intellectual debts as she is incisive about the ransomings and thefts of academic/poetic practice. Acknowledgments of a kind other writers might put in citations—including mention of the printers, copyists, research assistants, editors, secretaries, and other amanuenses who turn a poet’s fugitive thoughts into cogent, complete readable print—frequently become primary in Howe’s work. It is an irony, then, that my own thanks to Charlotte Maurer, Madeleine Bennett, and Christopher Looby—through whose intelligent good offices this essay appears—should be filed in notes.

19. Susan Howe, Souls of the Labadie Tract (New York: New Directions, 2007), 71. Further page references will be given parenthetically within the text.

20. Stevens, Collected Poems of Wallace Stevens, 158.