Jacques Rancière and African American Twoness

Have literary and cultural studies become disenchanted with disenchantment? There is evidence that, at least in some quarters, ideology critique may be losing the dominance it has enjoyed for the last two or more decades. Bruno Latour’s 2004 essay, “Why Has Critique Run Out of Steam?” now tops the list of the most frequently cited essays ever published in Critical Inquiry. Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, too, suggested that the dominant critical disposition fueling the “hermeneutics of suspicion” may have exhausted itself. And Peter Sloterdijk’s 1988 treatise A Critique of Cynical Reason is enjoying new bibliographic life in a number of recent critical conversations. The reception of these and other works suggests a new wariness––or at least a certain weariness––with the project of exposing the ideological forces at work in art and culture. Will the pendulum then swing back toward the more “theological” criticism that preceded the turn to ideology, criticism in which expressive culture is prized for possessing not just a unique set of properties but a transcendent aesthetic ontology, inimical to the worldly preoccupations of the political? Will a thousand (Harold) Blooms flower?1

Such is the fear––or, alternatively, the hope––for critics who anticipate that giving greater critical attention to matters of form and aesthetic effect will detach the discipline of American literary studies from any overt political concerns. But a return to aesthetic form does not necessarily mean a return to the same configuration of forms that made up the field before the historicist emphasis on ideology. If it did, the consequences would be politically dire indeed, inasmuch as whole disciplinary areas––such as African American literature, a concern of this essay––would all but disappear from the field. But rather than reestablish an earlier configuration of the literary field, renewed attention to the aesthetic might demonstrate instead that the political force of art lies precisely in its power of configuration, its use of sensory forms to reorder what is perceptible––and hence contestable––about a given social order. In this view, the faculties and forms we call aesthetic are actually the conditions of possibility for the political.

This notion––that aesthetics are the ground for politics––is at the heart of Jacques Rancière’s theory of democracy. Sensory forms are necessary for making political claims, Rancière argues, because any assertion of a wrong is also a picture of what is not—an absence in the world (a missing equality, a stolen freedom) intelligible only through the virtuality of a discernible form. Equality is a democratic truth while inequality is a historical fact, so only counterfactual images and as if locutions can speak across the gap that separates these otherwise incommensurable orders. Neither an unmasking of ideology nor a utopian counterworld, the aesthetic dimension of the political is a conjunctive space of appearance (“the polemical space of a demonstration that holds equality and its absence together”) where the presumption of equality in the demos is linked with a perceived inequality in the polity, through an expressive troping that allows for the naming of a wrong. Aesthetic forms are thus necessary to articulate the “warped conjunction” of what is and is not.2 Only figures, tropes, and the “quasi-bodies” visible in writing and images––inscriptions that do and do not refer to the facts of the world––are adequate to the task of formulating proper political speech.3

To anyone familiar with the current precepts of cultural and literary studies, these (still fairly gnomic) ideas about the relation between the aesthetic and the political are likely to appear counterintuitive, if not flatly wrong. Modern politics in particular has seemed far removed for the domain of aesthetics, attuned as the aesthetic is to contemplation rather than struggle and to form rather than history. For the “new revisionism” that has dominated literary scholarship in recent decades, aesthetics is usually treated as a “screen for unacknowledged ideological interests.”4 Acts of critical disenchantment thus typically aspire to strip away aesthetic illusion, setting politics and aesthetics in sharp opposition to one another. Can art and aesthetic experience––the enchantment produced by the senses––really conduct the agonistic contests of politics?

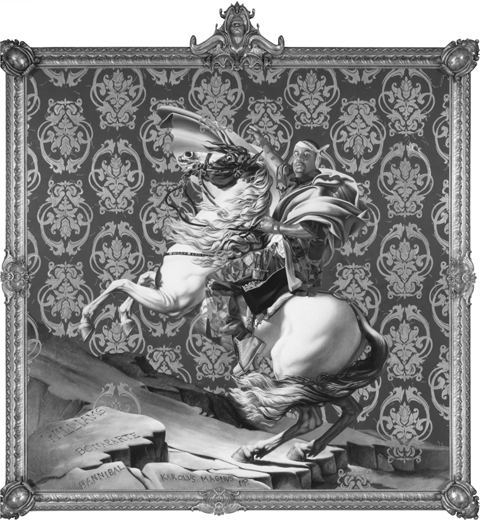

The prospect seems even more unlikely for any analysis of African American expressive culture, inasmuch as the black subject has been made to carry the stigma of bad particularity within the universalist schemas of Western aesthetic thought. As a result, the black diasporic artist, it seems, cannot but perform political work––the work of resistance, subversion, ironic signifying––whenever she takes up a pen or paintbrush, a fact that redeems her art from the false front of the aesthetic. The political dimension of most African American art is clear enough; from Phillis Wheatley and William Wells Brown to Edmonia Lewis and Jacob Lawrence, black artists have refuted white supremacist tenets and undermined demeaning conventions. But when we cast this art as performing chiefly a politics of resistance, we risk erasing the sometimes extravagant investment black artists have shown in art’s positive powers of enchantment––including some of the most suspect of Kantian powers: beautiful semblance (schöner Schein), claims to universal taste, and the consent made possible by an aesthetic community. Rancière’s way of conjoining the political and the aesthetic, I contend, can be illuminated and tested through examples from African American art, a body of cultural expression and thought that is itself an illuminating test of the way politics and art are configured in the broader field of American literature. Without dodging the damning complicity of aesthetic thought with histories of oppression, I probe Rancière’s ideas about the aesthetics of politics and the politics of aesthetics by exploring certain key ideas through the work of contemporary painter Kehinde Wiley. I then address a number of selected literary works from the turn-of-the-century moment in which an emphasis on shared perception in art is simultaneously a political assertion and the “twoness” of African American double consciousness is also a reworking of universalist ideas about beauty and sense perception. Common to both Wiley’s contemporary portraiture and some of the literary experiments in the era of Du Bois is an aesthetic of warped conjunction that merges the truth of democratic equality and the facts of historical inequality into a single compelling, enchanting form.

The paintings of New York artist Kehinde Wiley, many of monumental size and scale, reproduce an enduring tension between conventions of humanist art and the figure of the black subject. In Wiley’s paintings, young black men wearing hoodies, low-slung jeans, and throw-back jerseys materialize in the traditional spaces of European art history. They appear in the concave spaces of rococo ceiling murals, floating in air or resting on clouds. They emerge in the poses of painterly saints and martyrs, evoking the beauty of male suffering in the unending instant just before transcendent redemption. Wiley’s subjects claim the thrones and horses of royals who demonstrate sovereignty by merely presenting their bodies before the vision of their subjects. They occupy the allegorical landscapes in which beautiful bodies allow the idea of grace to speak through numinous flesh and appear amidst the props of wealth and power that distinguish the portraits of burghers and dukes. And Wiley’s figures don’t just occupy traditional scenes and styles of representation; they are also accorded the literal materials of this tradition: the hinged panels of a triptych, the massive gilded frame of the royal portrait, the intricate stitching of Old World tapestry.5

Lustrous and startling, these works display what Wiley calls a “contested relation” to a history of Old World portraiture and iconology, even as the paintings disable familiar habits of ideological analysis.6 It is quite possible to suspect a version of critical parody at work here, a playful yet aggressive puncturing of the grandeur and the claims to global dominance inherent in these European conventions. But dwell for even a short time on the care Wiley gives those conventions and their invocation begins to feel distinctly more loving than hostile. Visual incongruities, it is true, are what set the pictures vibrating with life. But those incongruities seem less like an attempt at deflation and more like a gesture of appropriation, a practice of creative anachronism designed to lay claim to a history of preexisting forms and the concepts they convey––the concepts of sanctified suffering, the human dignity affirmed in luxury, the inviolability of a sovereign body (a status that once belonged only to the body of the sovereign).

And yet, just as parody is an inaccurate description of Wiley’s practice (he is a self-described “contemporary descendant of a long line of portraitists, including Reynolds, Gainsborough, Titian, [and] Ingres, among others”), the notion of appropriation does not seem entirely apt, either, at least not if appropriation is understood as a correction of what has been false or exclusionary or a fulfillment of unrealized ideals.7 According to Wiley, “my intention is to craft a world picture that isn’t involved in political correctives or visions of utopia.” The aim is rather to practice “a craft that has evolved into a vocabulary of signs that tells one the subject is important.”8 The operative principle here, it would seem, is not the exposure of art’s blindness or bad faith but the principle of art itself, its apparent powers of signification, enchantment, and transport.

Wiley’s paintings are not best read as a correction of concepts, then, but as a practice of aesthetic play––in his words, “a perpetual play with the language of desire and power.” As I later show, in his eager embrace of Old World conventions of “the heroic, powerful, majestic, and the sublime” for painting contemporary black men, Wiley’s portraits resemble the willful, almost gleeful satisfaction evident in a number of narratives from the turn of the century that similarly insert black subjects into unlikely settings or spaces––counterfactual stories, mixed geographies, and speculative or fantastic histories.9 What is needed first, though, is a sharper understanding of how Wiley’s self-vaunted affiliation with European art history––not just with its forms and themes but also its tangible materials and textures––can be understood as political. The energies animating Wiley’s paintings are not energies of critical deflation but aesthetic intensity; how, then, can we consider these seductive surfaces, derived from hierarchical European vocabularies of “desire and power,” part of a politics that is not reactionary or quietist?

In trying to answer this question, we can turn to Rancière’s reinterpretation of aesthetic mimesis. Rather than thinking of art as a species of representation (imitation of an identity, an object, an ideal), it can be reconceived as a field of sense experience, a map or “distribution” of perceptible images and signs. What matters is not just the image or locution that appears but the economy of visibility that allows it appear, the more or less tacit “parcelling out” (PA 19) of different roles and abilities, delimited spaces and times, and intelligible possibilities as distinct from unthinkable events or impossible histories, that together make up the structural conditions of a given image or text. Every painting, novel, or film will thus model a “regime of sensible intensity” (PA 39) that connects facts, images, and concepts with intelligible forms of subjectivity and distinct relations of belonging. But, crucially, such structuring of sense experience is not merely the province of art. Every community or social order also rests on a distribution of the sensible: the slave understands the speech of the master but she cannot freely speak; the worker belongs to the polity but cannot leave the site of labor to appear in the places of governance because “work will not wait” (PA 12). Within a given social order, capacities of speech, appearance, and occupation are distributed according to a seeming law of necessity. But whereas rulers have resources (law and police powers) to ensure clear partitions between the spaces and allotments of sensory appearance and speech, works of art, with their birthright to commandeer the senses, can effect a material rearrangement of images and signs. (Hence Plato’s expulsion of the poet for the untethered source of his speech.) Art thus allows for variations in the perception of trajectories of history and the capacities of persons. In a formulation especially resonant for interpreting Wiley, works of art are really “ways of declaring what a body can do.”10

What, then, is “declared” about the bodies in Wiley’s paintings? In art, of course, declarations are not propositional but formal; they rely on sensuous forms to fuse the semantic and the expressive. Through his unabashed invocation of the formal textures and traditions of canonized art, Wiley is clearly making a declaration of beauty. Standing before these paintings, we have left behind the law of necessity––the rule that has governed black diasporic life for much of the history of modernity––and we’ve entered the domain of the beautiful where, according to the humanist aesthetics Wiley directly cites, we activate possibilities of freedom whenever we experience the uncoerced judgments that are based in aesthetic feeling. Wiley draws on a species of painterly beauty, moreover, that had adopted the highest powers of speech and action for the medium of the painted portrait. According to Rancière, the optical depth discovered and then perfected in Renaissance perspectival painting represents a key moment in the political possibilities of Western art. Mastering three-dimensional space allowed the mimetic surface of a painting to lay claim to powers of meaningful speech and action––the disclosure of a significant “‘scene’ of life” (PA 16)––that had previously been evinced only in the living speech and acts of aristocratic rulers. Even when a canvas depicted a king or a duke, painting as an artistic practice still retained for its own perceptual surface a depth of significance that could be endowed on any figure permitted to appear there.

The glamour of three-dimensional depth in traditional portraiture is a touchstone in Wiley’s bid for achieving beauty (the “luminosity I’m obsessed with, that light popping off bodies, that brings a certain hopefulness to something”).11 But it is precisely by recalling this high-water mark era of perspectivalism that Wiley triggers a crisis in the very aesthetic values that animate his portraits. For the original viewers of rococo murals or glossy Flemish portraits, of course, a black body could not have appeared in these spaces without violating exactly those canons of beauty that qualified the pictures as art in the first place. Or, more precisely, the figure of the black man or woman could appear and often did, but, according to those canons, the black subject can be beautiful only in selected postures and roles––the servile attendant, the stranger, the distant exotic or mythical chieftain. Suddenly, the quality of beauty seems to force on us a critical dilemma. If Wiley’s paintings are beautiful, then, as Kant instructs, all human subjects ought to be able to see the entrancing “luminosity” he has attempted to capture on his canvases. And yet such universal agreement is demonstrably untrue. But if the perception of beauty is therefore nothing more than the perceptual habits belonging to a particular place and age, then the crucial principle of aesthetic consent––the kind of judgment we affirm freely, uncoerced by the demands of necessity but also distinct from merely arbitrary or singular likings––is exposed as hollow. The distinct freedom belonging to the aesthetic begins to seem more like “a taste for necessity,” in Pierre Bourdieu’s resonant phrase, and aesthetics becomes no more than a law of historical necessity passed off in the guise of consent.12

Whereas aesthetic experience had previously seemed like a zone of freedom from necessity, it suddenly seems implicated in the work of naturalizing the sensory order of a given community. The implication seems clear. Do not trust your senses; they can only trap you in the untruths of ideology. What does the beauty of a Franz Hals painting offer his Flemish patron but proof, through the observer’s own eyes, that child slaves from the West Indies are as naturally pleasing as pet dogs are––and just as naturally unfree? And what does Wiley’s canvas show, for that matter, but that beauty (or “beauty”) is now only possible through the antiaesthetic knowingness of postmodern pastiche? When we reach this point, the critic who wishes to withstand the demand to confirm truth through an assent to beauty will be drawn down the rabbit hole of eternal political vigilance, consigning scholarship to unending acts of critical disenchantment.

Historical research in epistemology and perception, moreover, only gives further evidence of the need to bring a hermeneutics of suspicion to aesthetic experience. As Donald Lowe has shown, a profoundly different perceptual field emerged in European societies during the period Wiley references. The typographical revolution of the fifteenth century and the print culture it spawned, the discovery of the rational space of infinite extension and universal measurement, a shift in the hierarchy of the senses that gave primacy to vision, techniques of analytical reason that could detect connections and functions across different points in objective time and space––these and other related developments created an epistemic field in which sense experience must find its place in accord with the field’s spatiotemporal norms or lose any secure claim to offering real knowledge. Most important, the factors that shaped this dominant field of perception also shaped the epistemic foundations for art. Empty three-dimensional space and a universal model of history supplied a new foundation for “bourgeois perception” at the same time that they gave rise to new styles and genres of art.13

More recent scholarship in postcolonial history raises the same warning from a geopolitical angle. The styles Wiley references––Italian rococo, Dutch portraiture, English and French romanticism––originate at precisely the historical moment when, from out of a world of multiple civilizations, the European conceptualization of knowledge was both expanded and narrowed. Expanded because Western epistemology left behind knowledge organized by traditions of rhetoric and the personal transmission of wisdom in favor of operations of reason that detach knowledge from the knower and seek impersonal truths that pertain for all places and times. As Walter Mignolo summarizes it, “At the moment when capitalism began to be displaced from the Mediterranean to the North Atlantic, the organization of knowledge was established in its universal scope.” But the same expansion of knowledge through universalism also narrowed the geographical locale in which knowledge could be recognized as such. That is, while the rationality based on what Michel-Rolph Trouillot calls the “North Atlantic universals” opened up potent and even emancipatory formations of knowledge, it also closed out others that belonged to different geopolitical places. Thus when the scope of epistemology was reduced to the geopolitical spaces of Western Europe, Mignolo writes, it “erased the possibility of even thinking about a conceptualization and distribution of knowledge emanating from other local histories” of such places as China, India, and Islamic Africa. Given the structuring constraints for perception itself, the very possibilities through which sensory experience could generate aesthetic judgment or knowledge seems to have been restricted in advance, with damning implications for efforts to use aesthetic judgment to find and affirm truth.14

Yet it is also in precisely this context that the specificity of Wiley’s historical references begins to take on new significance. Wiley does not merely allude to the Atlantic history that grounded these structural categories of space and time. He also uses those perceptual spaces for his own images and the beauty he hopes they convey; three-dimensional space and linear historical time allow Wiley to position himself as a “descendant” of Old World masters. But a close examination of his paintings shows that he does not finally affirm or fulfill North Atlantic universalism so much as exceed it, through a logic (or illogic) we might call extra-universalism. The result is a new epistemic perspective disclosed through the commonality possible in sense experience, an aesthetic disclosure that closely matches Rancière’s definition of the political as “the art of the local and singular construction of cases of universality” (D 139).

The first clue to this political difference is the peculiar way Wiley’s subjects inhabit space. Like all subjects of portraiture after the introduction of perspective, the three-dimensional nature of Wiley’s black men emphasizes their emplotment in a world of bodies, objects, and landscapes akin to the world inhabited by the viewer. The perspectival resources of painting allow Wiley to underscore the way his subjects are possessors of bodies, living embodiments of the human. This way of occupying space, then, is one of the ways Wiley actively draws on the history of Western art as “a vocabulary of signs that tells one the subject is important,” and he means to express this truth about the portrait subjects he finds in places like Harlem and Columbus, Ohio. A project like Wiley’s thus helps to realize the aspirations of the European humanism that allocated for itself (and itself alone) the mission to discover and speak the truth about all mankind. And yet, in defiance of geometric logic, the bodies in these paintings do and do not belong to this representational space. In almost every Wiley painting, flattened patterns of ornamentation cut through the evocation of objective space, aligned neither with the background of the painted scene nor with the two-dimensional plane of the painting’s frame.

The effect of this ornamentation is subtle but highly significant. The odd placement of the repeating pattern allows Wiley to insinuate a different spatial field that exists somehow outside (or is it inside?) the dimensional coordinates represented by the rest of the painting. The plane in which they appear, in other words, is integral to the representational scene and yet still lies athwart its spatial coordinates, breaking free from the axes that would measure the total height and depth of the depicted field. It is as if these repeating ornamental figures are the abstracted traces of an otherwise invisible domain that is hidden in inner space or in an unseen externality. And although Wiley’s subjects have the “luminosity” and shaded contours of the traditional three-dimensional figure, they somehow emerge out of the flat surface of the ornamental plane, locating a kind of displacement or spatial syncopation in the field of rational geometric space.15

Floating both inside and outside the spatial extension of these scenes, intensely lifelike but somehow unconstrained by the coordinates of rational space––what kind of human subjects are these? How are we to locate them within the spaces and icons of a European humanism that allows them to be seen, yet seen only when objective space is folded or torn so as to disclose another dimension? These subjects belong to a more extensive perceptual world that somehow outstrips the merely three-dimensional world implied by these European scenes and styles. By becoming visible in this weird, almost unnameable spatial plane, they make perceptible what is otherwise invisible––a zone or dimension that the epistemic field structured through North Atlantic universals had erased or suppressed, or simply never dreamed of. Put another way, Wiley’s black generals, burghers, and saints are not fantastic or anachronistic; they are catachrestic. They give intelligible form to what is illogical or impossible for a given system or language. Wiley’s subjects show us forms of knowledge, spirit, or beauty that arrive from outside the bounds of the universal, which by definition has no bounds, no outside. In Wiley’s paintings, an Old World language of freedom and beauty comes to life as a global black vernacular, an expressive mutation that asserts a continuity between royal scepters and NBA jerseys, between iconic postures of kings and saints and the now global iconicity of hip-hop poses and fashions.

The continuity Wiley forges between these different distributions of the sensible is not smooth or uncontested. Some who gaze at his paintings, Wiley notes, see an artistic tradition “brutalized by someone who has a contested relation to it.”16 Such disagreement, moreover, is one sign of the political stakes at issue in perceptual experience. But, in creating what Rancière calls a “warped conjunction” of two different sensory regimes, Wiley has viewers perforce take part in the strange kind of polity that is an aesthetic community in which shared sense experience becomes a test of value and meaning apart from the world of necessity (“the world of commands and lots that gives everything a use” [D 57]). Thus while the universality of aesthetic experience is never achieved––and even Kant recognizes that agreement is “a mere ideal norm”––the appeal to a universal sense of beauty in any work of art becomes the basis of a demand for shared judgment about who and what can count, who can appear and speak, who can act and in what roles.17 The political force of the aesthetic, then, lies precisely in the “empty” idea of the universal, even as a given expression of it can only be a singular construction that particularizes the universal.

Hence the importance for Wiley of a nonironic idea of beauty. (He declares himself against “the type of artistic malaise” in which “joy is suspect and where absolute beauty is regarded with disdain.”)18 The axiom of universal beauty, like the principle of equality in democratic politics, is the site at which new or excluded particulars are able to appear and claim a place in a common world. Although the bid for aesthetic agreement may fail, in art as in political expression the domain of sense perception is a communal stage on which to include the uncounted, the “part of those who have no part” (D 30). Thus Rancière’s description of political expression can read like a gloss on the warping of humanist identities and roles disclosed on Wiley’s canvas: “Political activity is whatever shifts a body from the place assigned to it or changes a place’s destination. It makes visible what had no business being seen, and makes heard a discourse where once there was only place for noise” (D 30).

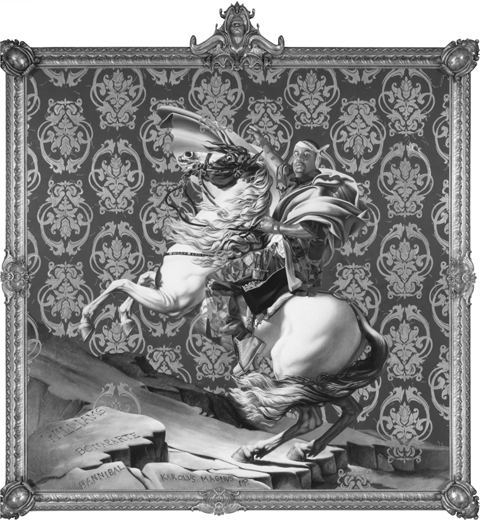

Wiley’s singular construction of the signs of North Atlantic universalism uncovers impossible subjects and deformed histories not as foreign contaminations of European spaces but as “warped deductions and mixed identities” (D 139) discovered by bending Europe’s own coordinates for defining beauty and knowledge. When a black subject in Wiley’s painting appears atop Jacques-Louis David’s uprearing horse from Bonaparte Crossing the Alps at Grand-Saint-Bernard, for instance, it realizes the impossible subject of a heroic black revolutionary, a figure that could not exist according to Enlightenment epistemologies––could not exist, even when that figure did exist. As Trouillot has demonstrated, the Haitian revolution was “unthinkable even as it happened,” a struggle for republican freedom that could not register in the cognitive coordinates of European history except as the unfreedom of savage revolt.19 Thus when Wiley’s canvas makes a young man from Ohio into a gorgeous Napoleon, the painting also gives an uncanny visibility to a historical black Napoleon who had long been uncounted in the archives, the revolutionary general Toussaint L’Ouverture, who was not recognized as a freedom fighter even as Napoleonic troops were struggling to defeat his fight for freedom. And it is not merely the outlines of codified masculine prowess that are the intelligible forms for black subjectivity in these paintings. Young black men are also the models for Wiley’s paintings of wealthy matrons and female saints and muses. His painting Passing/Posing (Female Prophet Anne, Who Observes the Presentation of Jesus on the Temple), for instance, features a thin young man in an Astros shirt gazing heavenward with arms outstretched, placing black masculinity under a sign of feminine grace and giving this portrait subject a singular appearance that cannot be parsed through a binary logic of sex. Although these images locate a wayward destination for David’s stormy image of Napoleon or for the likeness of Saint Anne, they demand of a community of viewers a judgment of agreement––literally, a new common sense––about the human form and the forms of the human.

Figure 13.1. Kehinde Wiley, Napoleon Leading the Army Over the Alps, 2005. Brooklyn Museum, collection of Suzi and Andrew B. Cohen, L2005.6, copyright ©Kehinde Wiley. Used by permission.

If Wiley is a “contemporary descendant” of Velázquez and Gainsborough, he is also an heir to the aesthetic experimentation of earlier diasporic intellectuals who drew upon art to give deformed form to the equality––axiomatically true, historically absent––of the black subject. Du Bois is the best known, but he can be counted as one of a generation of writers and artists who looked to the sensory properties of art to pry open, through incongruous folds in time and space, the closed universalism of North Atlantic history. To compare Wiley’s visual art with literary production by writers such as Du Bois, Sutton Griggs, James Corrothers, and Pauline Hopkins is not to argue for either a uniform black aesthetic or a static history of political subordination stretching between Du Bois’s moment and our own. It is instead to focus on the ability of art itself to insist on relations between otherwise incommensurable fields of sense experience as a way of making those relations seen by a community of readers or viewers. If formal discontinuities of this kind are especially pronounced in postmodernism, that is because the art of our time often exploits art’s inherent potential to display or distort––and not just to reproduce––the categories of time and space that condition modern “bourgeois perception.”

Figure 13.2. Kehinde Wiley, Passing/Posing (Female Prophet Anne, Who Observes the Presentation of Jesus on the Temple), 2003. Brooklyn Museum, Mary Smith Dorward Fund and Healy Purchase Fund B, 2003.90.2, copyright © Kehinde Wiley. Used by permission.

Literature, too, possesses these resources. In fact, the reflections on and disruptions of sensory perception in Wiley’s canvases may owe a special debt to literary art and the transformations it can deploy through what Rancière calls the field of “unsensed sensation” unique to the literary.20 Du Bois, the sociologist turned novelist, is a telling case in point. In an essay on the black public sphere, Houston Baker makes his own asynchronous fold in cultural history by comparing the compositional principle in Souls of Black Folk to the technique of cinematic montage, and the analogy is apt. Superimposing Berlin social science and Black Belt communal life, merging the lyricism of the sorrow songs and Richard Wagner’s stormy melodies, Souls presents a composite form of literary analysis that makes critical revelations by way of conjoined incongruities.21 For a reader versed in film history, then, a visual technique like montage captures well the formal interface between different sensible orders that Rancière identifies as the political potential of art. But, even as it anticipates cinematic montage, Souls of Black Folk can be seen as exploiting already existing aesthetic resources, namely, the formal resources of the novel. In fact, in Rancière’s account it is actually the nineteenth-century novel that first innovated the formal possibilities that are later realized visually in modernist painting and film. As a species of writing that broke free from the rule-bound decorum of higher genres, the novel seized the chance to bring forms of intelligibility to a body of empirical materials––commonplace objects and ordinary actions––that previously had no place in established hierarchies of artistic form. Exploiting this capacity, the “triumph of the novel’s page” (PA 17) was its ability to act as a space of interface and exchange between incommensurate distributions of signs and literary images.

Thus the “literary heterology” (D 59) of the novel allowed writing to break up and reconfigure approved allotments of speech and appearance. When the fiction of Flaubert depicts instead of instructs, when Melville’s “Bartleby” distills the power of indeterminacy to break up well-ordered distributions of subjectivity and metamorphose strange new speaking bodies, then the page of the novel becomes an open space for making legible new maps of the visible and the sayable.22 If Souls looks ahead to cinematic montage, it also looks back to the innovations of the novel inasmuch as Du Bois innovated a form able to make expressive black sounds and laboring bodies perceptible on the same plane as historiographical facts and already canonized lines of verse. It shouldn’t surprise us, then, that even before he published the essays that would become Souls of Black Folk, Du Bois attempted to write a work of fiction that could capture what he saw as the “twoness” of African American experience, the heterogeneity built into the awareness that the subjective experience of the black American is cut off from the object of the “negro” as it is seen by white folks. In trying to give this heterogeneity a novelistic form, moreover, Du Bois’s experimental narrative approached the problem of double consciousness precisely by transforming universal categories of rational space. Like a number of other speculative stories produced by African American writers during the same period, Du Bois’s narrative allows uncounted bodies and counterfactual histories to emerge through the heterologies of the novelistic page.

In this never completed story (eventually titled “A Vacation Unique” by an editor), a white Harvard student is persuaded by a black classmate to undergo a “painless operation” that will make him temporarily black. Immediately after the procedure, however, the student is stunned to discover that there has been a profound rupture in his relation to time and space, a break or transformation that has brought him into a distinct spatial region. Already awaiting him there, the black classmate explains the mystery: this dimension is the space of blackness. “By reason of the fourth dimension of color,” the black student informs him, “you step into a new and, to most people, entirely unknown region of the universe––you break the bounds of humanity.”23

Scholars believe that Du Bois probably began his sketches for this novel when he was an undergraduate at Harvard himself, a time when he would have been busy mastering the epistemic principles of the highest transatlantic knowledge. But it is clear he was also reading novels. In fashioning his narrative, he was borrowing directly from the “scientific romances” of British writer Edwin Abbott and the American C. H. Hinton, fiction that had been widely read beginning in the 1880s. Abbott’s novel Flatland tells of geometric races––circles, squares, and triangles––that live in a two-dimensional universe, whereas Hinton wrote sketches such as “What Is the Fourth Dimension,” in which he speculates on the lives of “beings” who inhabit a four-dimensional world beyond our powers of perception. Even more starkly than other kinds of stories, these speculative tales of alternative geometric worlds demonstrate the ability of fiction to reconfigure the particulars of sense experience. While the zone of the fourth dimension has no “direct point of contact with fact,” Hinton writes, the formal resources of fiction produce “a gain in our power of representation. They express in intelligible terms things of which we can form no image.”24

But while Hinton’s story abandons the three-dimensional space that structures “bourgeois perception” (and also anticipates the multiperspectivalism of perception in our age of new media), his fictional experiment actually affirms the idea of space as an infinite and homogeneous extension. It therefore retains the idea that the physical dimensions of the human world are already settled forever. In Hinton’s fourth dimension, as in Abbott’s Flatland, there are subjects but no humans. That is, when the form-giving power of fiction allows Hinton and Abbott to look into otherwise invisible domains in space, they discover there beings who possess bodies and creaturely life, but who are by definition nonhuman––triangles, for instance, or the qualitatively deeper “beings” of Hinton’s fourth dimension, complex creatures for whom we humans are as shallow as triangles seem to us. In Hinton and Abbott, therefore, disclosing unseen spatial worlds only further proves that the world consists of a totality reducible to known geometric rules, a universe in which no region or zone––not even infinity––can exceed these existing powers of measurement. More important, any speaking beings discovered outside of the three-dimensional will be something other than human: any alterior zone in space has to contain an alterior form of creaturely being.

But, in contrast with Hinton and Abbott, in Du Bois fiction does not extend perception to new domains of nonhuman life, rather, it insists on a new way counting the human. For in Jim Crow America, where the black subject is “a thing apart,” human life has been miscounted or mismeasured. As the narrator puts it to the newly inducted black student, “Your feelings no longer count, they are not a part of history” (223). Only when the lived experience of the black subject is disclosed in fiction do the real contours of the human appear, uncovering a distinct zone of human thought and feeling that is distributed throughout a three-dimensional world that still remains oblivious to it. Thus the fourth dimension of color is the surplus region needed in order to see the humanness of the black subject. Du Bois’s model here is not a theoretical universality but a polemical one: it posits a human totality in order to make manifest the false delimitation in the way a given order has assigned purportedly natural properties and dwelling places to different bodies. Crucially, however, disclosing this dimension is not simply a matter of including what has been excluded, since the very discovery of an unseen and unimagined dimension of the human means that the existing metrics for identifying human life, its distribution of roles, capacities, and properties, is fundamentally wrong.

Picturing this wrong, giving it a form in fiction, is at once a political claim and an aesthetic expression, a formal demonstration of what the social order denied: that black subjects are “speaking beings sharing the same properties of those who deny them these” (D 24). Although Du Bois’s unusual story never appeared in print, it shares the same feature of aesthetic warping with a number of other counterfactual stories by African American authors published not long after Du Bois worked on his narrative. In these narratives, fiction discloses invisible regions not of space but of history. Sutton Griggs’s novel Imperium in Imperio, for instance, doubles the historical order of Jim Crow America by imagining a secret black republic dispersed throughout the United States, an organized polity of more than seven million black people with a constitution, an elected congress, a judiciary, and an army. Although this secret nation adheres to ideals of Jeffersonian liberty, faced with the failure of the U.S. state to protect black lives and rights, this republic is by the end of the novel poised on the brink of a war of insurgency against the United States.25 Similarly, a story by the Chicago writer James D. Corrothers, “A Man They Didn’t Know,” tells of a military alliance of Japan, Mexico, and Hawaii, a joint Pacific force that recruits black deserters from the U.S. Army along with angry Japanese Americans for an invasion of southern California. A contingent of black fighters eventually becomes the decisive military unit in the invasion.26

As images of history and historical time, of course, these stories are wholly implausible. Newly disenfranchised, black men at the turn of the century enjoyed even less political agency and military standing than the freedmen who were their fathers. We might be tempted, then, to read these fictions as expressing a logic of wish fulfillment. But rather than signifying a flight from the real, the political valence of these stories lies precisely in their historical impossibility. By representing unthinkable events and tables-turned histories, the fictions allow black subjects to appear in the places they are supposed to be incapable of occupying. The narratives thus insist that the allotted positions of any subject or group are not determined by their different properties (as a law of necessity would have it) but only by history’s contingencies. A more egalitarian order could have––indeed, necessarily would have––produced a different history. Alongside the history of what was or what is, there exist innumerable trajectories of what could have been, zones of counterfactual time and events that only fiction is capable of bringing before our senses. And, simply by presenting such fictions, Griggs and Corrothers insist on their own capacity as subjects of history, not merely as history’s passive objects, thereby demonstrating political properties they are not supposed to possess and appearing in subject positions they are presumed incapable of occupying. Their stories can be refuted as mere fiction, but their own demonstration of political agency cannot––that agency can only be disputed, which dispute thereby confirms the black subject as a political interlocutor with those who would deny the very possibility.

Like the fourth dimension, these counterfactual histories are a site for enunciating a wrong, for speaking as part of a polity in which their authors have no part and thus introducing a “twist that short-circuits the natural logic of properties” (D 13). In another novel from this era, the same aesthetic turning or torsion allows fiction to reconfigure the human form itself, a transformation of the black body through which racial difference becomes a form of sheer surplus that demands a new logic of humanity. In her novel Of One Blood; or, The Hidden Self, Pauline Hopkins envisions a counterfactual that is simultaneously a hidden geographic space and an unthinkable history. Through the novel’s complicated plot, Hopkins’s African American protagonist, Reuel, finds his way to an ancient, hidden city surviving in modern Africa. Much of this section recycles the topoi of popular imperial romance, but formulaic exoticism eventually gives way to something stranger. Most strikingly, in this city, Telassar, there are forms of life that result from a kind of ancient cryogenics. The people of Telassar have been able to preserve the “natural appearance” of living organisms, for instance––not only organic life such as flowers but also human beings: “We preserve the bodies of our most beautiful women in this way,” a priest explains to Reuel. And when Reuel is later introduced to Queen Candace (a descendent of the original Cleopatra), she is described in terms that evoke a similar idea of reanimation: “Yes; she was a Venus, a superb statue of bronze, moulded by a great sculptor; but an animated statue, in which one saw blood circulate, and from which life flowed.” Candace’s palace apartment is guarded by “beautiful girls” who seem likely candidates for the preservation program, if they aren’t already its products: “Each girl might have posed for a statue of Venus.”27

What are we to make of these strange fictional bodies, uncomfortably evocative of a collection of African Stepford wives? The women in Telassar seem largely consigned to the work of reproduction and preservation. But reproduction in Hopkins’s novel is hardly the sort of passive transmission that makes women merely the bodily vessel of history. Instead, the strange bodies in Telassar seem to be a different order of life, even a unique ontology, for which there is no modern name. That is, they present people assumed to be long vanished who not only live and flourish in modern history but who possess knowledge of organic life superior to what is known by the inhabitants of “out-world” (130). Women are bodies that bespeak the forms of knowledge and human life unique to this “unknown” zone of world history.

The very strangeness of these figures, in other words, is the proof of their world historical significance. To begin to grasp this paradox, we can see these bodies as being akin to the “inconceivable bodies” that Judith Butler has discussed in her analysis of intersexed persons. For Butler, what makes these living bodies inconceivable is not anything inherently mysterious or unnatural about their status as human bodies but rather the position of those bodies outside a knowledge system that defines the exhaustive classes of the human through two sexes. Within that system, the intersexed body “becomes a point of reference for a narrative that is not about this body, but which seizes upon the body” in order to tell a story of what is conceivably human. (“They can’t conceive of leaving someone alone,” one intersexed person says of the medical establishment.)28 Hopkins’s fictional bodies, and the Telassar inhabitants generally, are hardly real in the same sense, but they are similarly “inconceivable”––that is, their status as unreal and fantastic has the same discursive origin in authoritative narratives within which they cannot be other than impossible or inconceivable objects.

Hopkins is emphatic on this point. As a living African civilization, fully coeval with European societies, Telassar is literally an inconceivable history. A white character declares that Africa is a “played-out hole in the ground” (159) holding “nothing but the monotony of past centuries dead and forgotten” (93). Hopkins knew very well that most contemporary scholarship assumed African peoples had long ago fallen out of the forward-moving currents of world history, and any effort to represent their ongoing life as coeval with Anglo-European history would be literally incredible; as her narrator puts it, “the modern world would stand aghast” (115). Quite simply, there is no conceivable realism for a story of Africans or African Americans who belong as Africans to modern world history. The novel’s strange spaces and bodies are thus part of the inevitably fantastic language Hopkins invents for representing African humanness. Fantasy is here the realism of an impossible modern history.

Rather than insist that black people are just like white people, Hopkins presents the black subject as what Rancière calls a “surplus subject” (D 58), a figure inassimilable to the current configuration of the human who still must be counted as part of the whole. As with Wiley’s black male prophetess, or Du Bois’s white-turned-black student who dwells in the fourth dimension, in Hopkins’s novel an aesthetic form is able to free sense perception from the “natural logic of properties” in order to see in a single image both what is and is not: the equality of the black subject. The century that divides Hopkins and Wiley, of course, introduced any number of significant changes in the political subjection and subjecthood of African diasporic peoples; Wiley’s paintings are as concerned with male sexuality and intragroup relations as with the problem of the color line that is uppermost for Du Bois and Hopkins. If, as Rancière claims, works of art are “ways of declaring what a body can do,” the declarations of these artists are also explorations of changing conditions that give ever new shapes to the souls and bodies of black folk. The open nature of art’s declarations––openly claimed and open to change––is at the root of what makes a work of art political. Taken together, the catachrestic forms in these examples of African American expression allow us to see in a kind of heightened way the political dimension of all art, the domain that allows for the ongoing destruction and rearticulation of the human for the sake of opening a common perceptual world to what we do not yet know.

Notes

1. Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, “Paranoid Reading and Reparative Reading; or, You’re So Paranoid, You Probably Think This Introduction Is About You,” in Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, ed., Novel Gazing: Queer Readings in Fiction (Durham: Duke University Press, 1997), 1–37. Rita Felski discusses other influential works that criticize the hermeneutics of suspicion and addresses the question of “theological reading” in Uses of Literature (Oxford: Blackwell, 2008). Also relevant is Jacques Rancière’s critique of Pierre Bourdieu, “Thinking Between Disciplines: An Aesthetics of Knowledge,” Parrhesia 1 (2006): 1–12. Rancière criticizes Bourdieu’s sociological analysis of culture and art as “the idle logic of demystification” (11).

2. Jacques Rancière, Disagreement: Politics and Philosophy, trans. Julie Rose (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999), 14. Subsequent page references, following the abbreviation D, will be cited parenthetically in the text.

3. Jacques Rancière, The Politics of Aesthetics: The Distribution of the Sensible, trans. Gabriel Rockhill (New York: Continuum, 2004), 39. Subsequent page references, following the abbreviation PA, will be cited parenthetically in the text.

4. Winfried Fluck, “Aesthetics and Cultural Studies,” in Emory Elliott, Louis Freitas Caton, and Jeffrey Rhyne, eds., Aesthetics in a Multicultural Age (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), 80–81.

5. Examples of Wiley’s portraits are available at his Web site, http://www.kehindewiley.com (accessed April 22, 2011). Also see the publications Kehinde Wiley, Columbus (Columbus, OH: Columbus Museum of Art, 2006); and Kehinde Wiley and Brian Keith Jackson, Black Light (Brooklyn: powerHouse, 2009).

6. Kehinde Wiley, interviewed by Roy Hurst in “Painter Kehinde Wiley,” National Public Radio, June 1, 2005.

7. “Biography,” http://www.kehindewiley.com/main.html (accessed April 22, 2011).

8. Wiley quoted in “Exhibitions,” American Arts Quarterly 21, no. 4 (2004): 51.

9. “Biography,” http://www.kehindewiley.com/main.html (accessed April 22, 2011).

10. Rancière, “Thinking Between Disciplines,” 11.

11. Wiley quoted in Lauren Collins, “Studio Visit: Lost and Found,” New Yorker, September 1, 2008.

12. Pierre Bourdieu, Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste, trans. Richard Nice (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1984), 374ff.

13. Donald M. Lowe, History of Bourgeois Perception (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982).

14. Walter D. Mignolo, “The Geopolitics of Knowledge and the Colonial Difference,” South Atlantic Quarterly 101, no. 1 (2002): 57–96, quote from 59; Michel-Rolph Trouillot, “The North Atlantic Universals,” in Immanuel Wallerstein, ed., The Modern World-System in the Longue Durée (Boulder: Paradigm, 2005), 229–37.

15. On the transformations modernist art made to the Kantian idea of space as “the realm of the external,” see Susan Stewart, The Open Studio: Essays on Art and Aesthetics (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005), 25. Stewart notes that when modernism made space a source of abstract figures, it was actually returning to what had long been the case for the way space functioned in Byzantine and Islamic art. While some of Wiley’s patterns recall styles of ornamentation from French rococo or Victorian decorative arts, they sometimes invoke styles from Islamic cultures. Richard Iton discusses the “surreal” elements that have long been part of black expressive culture in his study In Search of the Black Fantastic: Politics and Popular Culture in the Post-Civil Rights Era (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008).

16. Wiley quoted in Hurst, “Painter Kehinde Wiley.”

17. Immanuel Kant, Critique of Judgment, trans. J. H. Bernard (New York: Simon and Shuster, 1970), 76.

18. Wiley quoted in press release for DOWN, an exhibition at the Deitch Project Gallery, New York, 2008. See “The Art Blog: Roberta Fallon and Libby Rosof,” http://theartblog.org/2008/11/beautiful-and-not-in-new-york (accessed April 22, 2011).

19. Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (Boston: Beacon, 1995), 73.

20. Jacques Rancière, “Deleuze, Bartleby, and the Literary Formula,” in The Flesh of Words: The Politics of Writing (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2004), 151.

21. Houston A. Baker Jr., “Critical Memory and the Black Public Sphere,” in Black Public Sphere Collective, ed., The Black Public Sphere (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995), 23–25. I discuss Du Bois’s strategic use of incongruities in Frantic Panoramas: American Literature and Mass Culture, 1870–1920 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009), 280–302.

22. For Rancière’s discussion of Melville, see “Deleuze, Bartleby, and the Literary Formula,” 146–64. For his extended analysis of Flaubert, see “Why Emma Bovary Had to Be Killed,” Critical Inquiry 34 (2008): 233–48.

23. W. E. B. Du Bois, “A Vacation Unique,” in the appendix to Shamoon Zamir, Dark Voices: W. E. B. Du Bois and American Thought, 1888–1903 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995), 217–25, 221. Subsequent page numbers will be cited parenthetically in the text. I have discussed this text at more length in “The Fourth Dimension: Kinlessness and African American Narrative,” Critical Inquiry 35 (2009): 270–92.

24. C. H. Hinton, Scientific Romances (London: Swan Sonnenschein, Lowrey, 1886), 30–31.

25. Sutton E. Griggs, Imperium in Imperio (New York: Modern Library, 2003).

26. James D. Corrothers, “A Man They Didn’t Know,” Crisis 7 (December 1913): 85–87, (January 1914): 135–38.

27. Pauline Hopkins, Of One Blood; or, The Hidden Self (New York: Washington Square Press, 2004), 131, 137, 136. Subsequent page numbers will be cited parenthetically in the text.

28. Judith Butler, Undoing Gender (New York: Routledge, 2004), 64.