5‘Fortune ce mestier m’aprist’1

Christine de Pizan as writer, teacher, and Voice of Wisdom

Ellen Thorington

Christine de Pizan (c. 1365–c. 1431), considered to be Europe’s first professional woman of letters, became a writer largely out of necessity. Widowed in 1390 with three children, her mother, and a niece to support, Christine needed to find a way to make ends meet since amounts owed to her late husband remained unpaid, debts had piled up, and she was involved in a number of lawsuits.2 In becoming a writer and publisher, Christine made an unusual choice for a woman. She became a writer, a métier most often associated with men; she wrote that Fortune had transformed her into a man and taught her the craft so that she and her dependents could survive.3 Both she and her contemporaries remarked on the novelty of a woman writer; Christine suggested that a number of princes may have accepted her works for this reason rather than for the worth of their contents.4 Yet it is precisely the unique perspective of a woman who writes that makes Christine such an important figure for a discussion of women and work.

Christine has left us a number of autobiographical and semi-autobiographical details that reveal her experience as a working woman. For example, her works relate her ideas on what it meant to be a writer, the circumstances that brought her to take up her pen, and what she hoped to accomplish through the work of writing. She was a mindful writer, concerned that her works show by example the very matter she intended to portray. Christine saw herself as a teacher, and much of her work concerned the education of the young, the instruction of princes, and the ways to good government.5 This reflects the concerns of the period in which she was writing, for France was in real crisis: King Charles VI suffered from mental illness, the dauphin Louis of Guyenne was too young to govern in his stead, and the ensuing power struggle led the country into civil war. Christine’s work was intricately connected to the fate of her adopted country and derived from her combined responsibilities to her family, community, and France as a whole. In the face of political crisis, Christine presented herself as a Voice of Wisdom, a writer whose qualities as a humble woman and mother allowed her to call on the authority of the Virgin Mary and to forge an affinity with the queen of France, in order to offer her own wisdom, in text and image, for the betterment of France.6

On becoming a writer

Christine’s entry into the professional world beyond the home began around 1390, following the tragic death of her young husband, Etienne de Castel, from an epidemic. However, little trace remains of the earliest years of Christine’s career, the period from her husband’s death to 1399, which marks the date she viewed as the start of her literary career.7 Much of what we know comes from a few references in her more autobiographical works; the rest must be extrapolated from these writings and from what we know of her and of her society. To further complicate matters, the very notion of work and most particularly of women’s work at the time when Christine lived is problematic, for expectations about what work could entail for women varied widely according to a woman’s social, economic, and marital status, as well as her stage in life.8 Christine was no exception to this rule: as a young married woman, her work was primarily based in the home, where she described herself as occupied with childbearing and the ‘affaires que ont communement les mariees’ (tasks common to married women).9

Christine had been encouraged in learning and probably educated in large part by her father, Thomas de Pizan, although her mother seems not to have approved.10 Until she became a widow, Christine did not have time for serious study and a program of self-education; it was only when she was alone and confronted by financial disaster that she made the decision to become a writer to support herself and her family.11 Like many women in her circumstances, Christine’s options were limited. Widows could remarry, invest in real estate if they had the funds, take over the husband’s business (particularly in the artisan and merchant classes), or take religious vows and enter a convent.12 Yet Christine, whose marriage appears to have been very happy, stated that she had no desire to remarry.13 Given that her finances left her no possibility of investing—in fact she was obliged to sell some property to pay debts—Christine had even fewer options.14 Entering a convent would have required her to find an alternative solution for her dependants. Instead, she chose to follow in the footsteps of both her father and her husband, taking up the life of the scholar.15 This was a remarkable choice: at higher levels of the social hierarchy, women were excluded from many positions, such as the posts of notary and royal secretary held by her husband Etienne, and from earning the credentials required for them.16 With no business, as it were, for Christine to continue, she had to find her way through a different route. It seems most likely, as Charity Cannon Willard has suggested, that Christine’s first steps were to use her husband’s contacts to earn some money through copy work.17 This would have been essential to her success as it gave her a network within clerical and bureaucratic circles and afforded her continued access to the nobility and to potential patrons.

Circumstantial evidence found in both Christine’s handwriting and her rhetorical style suggests a strong association with the chancellery, her husband’s workplace. The handwriting of scribe ‘X’, identified as that of Christine by Gilbert Ouy and Christine Reno, is characterised by ‘une exubérance’ and a love of ‘jeux de plume’, flourishes of the pen that were often practised by chancellery clerks.18 It is quite possible that Etienne de Castel taught her the form of calligraphy he used as a notary, perhaps so she could help him with his work.19 Her rhetorical style also demonstrates this influence, for it contains ‘echoes of the style clergial and curial … Latin styles … that were especially influential in the juridical language used in the Chancellery where Christine’s husband and many of her friends worked’.20 The fact that both Christine’s style and handwriting appear to have been influenced by her husband and his workplace—and that she may have helped him with his work—corresponds to contemporary practice, particularly in the crafts. It was quite common for women to work along with their husbands or parents in artisanal production and for women to learn a craft within the family.21 The suggestion that Christine began first as a copyist at the chancellery thus seems a natural progression, the outgrowth of skills and relationships dating from her marriage.22 Willard also proposes that Christine may ‘have been a sort of editor for an atelier which copied literary manuscripts’, perhaps through her connection with the workshop responsible for the dissemination of the first Boccaccio manuscripts.23 This type of position would have given her access to a number of texts and sources that she later cites in her works.24

Although it is uncertain how Christine managed financially during the early years of her career, her survival and subsequent success may be due in part to the influence of the queen, Ysabel of Bavaria (1370–1435).25 There is some suggestion that she served as chamberiere (an honorary position that could encompass a number of different functions) to the queen beginning in the early 1390s; she herself employed this term in a letter to Ysabel but did not mention the position elsewhere in her works.26 Certainly she seems to have worked in close association with the queen: Ysabel’s accounts show a number of gifts given to a certain Christine; Christine also figures among the list of those receiving New Year gifts in 1402 and 1405, suggesting that she was a member of the queen’s entourage at that time.27 Such a position would have placed her within the queen’s sphere of influence, eventually given her access to works owned by the queen, and left her well situated to encounter potential patrons among the men and women frequenting the queen and her ladies. Ouy, Reno, and their colleagues Olivier Delsaux and Inès Villela-Petit, hypothesise that Ysabel may have had a hand in the composition of Christine’s own atelier. They suggest that Christine presented the first copy of her collected works, Chantilly, Bibliothèque du Château (formerly Musée Condé) MS 492, begun in 1399, to the queen. Wishing to reward the author, Ysabel likely exerted her influence to help Christine enlist a brother or cousin of a scribe in her service. It was this new recruit, Pierre de la Croix, who probably helped initiate Christine in the art of book making, and Pierre likely trained another scribe, whose name is still not known. These two scribes became Christine’s principal collaborators; the resulting atelier would have worked from its outset under the protection of the queen.28 Not insignificantly, Christine dedicated a number of works to Ysabel throughout her career, including London, British Library, Harley MS 4431. This exquisitely decorated manuscript also contains Christine’s collected works, and is one of only five such surviving collections to have been produced in her own workshop.29 Both its dedication and clear connection to Ysabel testify to a continuing—and long-standing—relationship between patron and author.

When she completed the Livre de l’advision Cristine in 1405, Christine was clearly an accomplished scribe, writer, and publisher. In this work, she dates the beginning of her literary career to 1399 and describes her development as a writer.30 She likens it to that of a workman (ouvrier), who refines his work as he spends more and more time on it.31 From ‘forging’ ‘pretty things’ that were ‘lighter’ (legiere) in subject, she has moved on, employing a more subtle style that reflects her study of ‘diverses matieres’ (diverse subjects).32 In addition to developing her subject matter and style, Christine also demonstrates her knowledge as a bookmaker; her easy use of technical vocabulary reveals a familiarity with the techniques employed by copyists and illuminators.33 For example, when referring to the ‘XV volumes principaux’ (15 principal volumes) that she has composed and the ‘LXX quayers de grand volume’ (70 large quires) in which they are contained, Christine writes as someone experienced in manuscript composition.34 By 1405, then, Christine has plainly moved beyond the status of amateur connoisseur to become a master of her craft.35

The testimony of the Livre de la cité des dames, also completed in 1405, further details Christine’s experience as a master-editor, one who hires illuminators and executes manuscripts. She speaks in particular of Anastaise, a female manuscript illuminator specialising in ornamental borders whose skill as an artist is so great (tant est expert) that Christine claims it could not be surpassed by any other artisan in Paris: ‘qu’il n’est mencion d’ouvrier en la ville de Paris … qui point l’en passe ne qui aussi doulcement face fleureteure et menu ouvrage qu’elle fait ne de qui on ait plus chier la besongne’ (one cannot find an artisan in all the city of Paris … who can surpass her, nor who can paint flowers and details as delicately as she does, nor whose work is more highly esteemed).36 Christine was very familiar with Anastaise’s work, for the illuminator had completed several projects for her.37 From this we can see that Christine hired illuminators for her work, she was familiar with the illuminators available in the Paris area, and she was not the only woman working in the book trade at the time.

Indeed, her work as a master-editor placed her within the flourishing book trade in Paris, a space within which women could and did take on a professional role. Taille rolls indicate that, like many trades, book making was often a family affair, where women worked alongside husbands, fathers, or sons.38 Nevertheless, women’s participation in the book trade was ‘probably pervasive, but for the most part invisible’; they trained primarily within the family rather than through formal apprenticeships and their names rarely appear on official documents.39 Only in the case of widows like Jeanne de Montbaston, a mid-fourteenth-century illuminator who took over her husband’s business, are women’s names recorded as members of the book trade.40 Christine thus fits into the latter model: although she did not take over a business from her husband, as a widow working as copyist and master-editor, she would not have been that unusual a figure. It was her work as author and scholar that took her beyond more conventional roles for women and enabled her to develop an international reputation. As Christine remarks in the Advision, it is her way of life (maniere de vivre) in scholarship (l’estude) that causes princes to take notice and to spread her works to different realms (pars et pays divers).41

The fact that Christine viewed herself as a scholar is essential, for it underlies both the philosophy of her work and her uniqueness as a woman writer. For Christine, the scholar has an obligation to share wisdom with others. Like her father, who was an advisor to King Charles V and whom she describes as counselling princes about everything from peace and war to the weather, she too needed to share her wisdom.42 She, however, adapted the work of the scholar to her own situation and her own gender, becoming a female Voice of Wisdom. In taking up her pen and working her way into the life of the scholar, Christine gained for herself a position where she too could be the advisor of princes, and where she was able to make her own contribution to the betterment of society.

Christine’s vision of the writer’s role

In her works, Christine expresses a clear notion of what it means to be a woman writer in the fifteenth century and the types of responsibilities she attaches to this. The experience was not always positive: she remarks rather wryly on contemporaries, specifically the ‘princes benignes’ (gentle princes), who sought out her works because it was seen as unusual (non usagee) for a woman to write.43 While being a novelty spread her renown and helped disseminate her works throughout Europe, Christine was not always taken seriously as a writer because of her gender. Her critics seem to have had difficulty believing that a woman could have composed her ‘compillacions et volumes’ (collections and volumes), arguing instead that they must have been written for her by ‘clercs ou religieux’ (scholars or religious men).44 Christine, with characteristic spirit, has Dame Opinion in the Advision dismiss such naysayers as ‘ignorans’ (ignorant) and unfamiliar with works that speak of the valiant wise women (vaillans femmes sages) of the past who were learned (lettrees) and who even served as prophets (profetes).45

Even with such determination, it was not easy for a woman to become a writer in the fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries. As Jacqueline Cerquiglini-Toulet argues, Christine found two different solutions to the problem: on the one hand, she transformed herself, figuratively speaking, into a man, as we see in the Livre de la mutacion de fortune (1403); on the other, she made herself into a woman of unparalleled excellence (se faire femme superlativement), which was the solution she employed from the Cité des dames (1405) onwards.46 Ilse Paakkinen contends that as a woman transformed into a man, Christine could take up where contemporary men had failed in their duty to become womankind’s defender.47 Her ability to engage in a different mode of feminine exegesis, re-reading older anti-feminine narratives in new and more positive ways, formed a large part of the Cité des dames and is particularly evident in the learning process she underwent to become became a female scholar under the tutelage of Ladies Reason, Rectitude, and Justice.48 I would argue that Christine in fact adapted the role of writer to suit her own ideals and personal experience: she fashioned her own concept of what it meant for a woman to take on an authorial role as well as the responsibilities entailed by that that role.

Christine’s notion of the scholar was largely inspired by her father’s example. In the Mutacion de fortune she praises his learning, likening it to a treasure of precious gems (pierres precieuses) collected at the fountain of Wisdom.49 Yet even as she admires his learning, she notes that her gender was an obstacle preventing her from following his example. Because she was born a girl (pour ce que fille fu nee) she could not inherit the riches of this fountain, even though this was due more to custom than for any other reason (plus par coustume que par droit).50 Indeed, until her husband’s death and despite what she called a natural inclination to scholarship, various impediments kept her from fully profiting from learning. Christine’s mother preferred that she stick with spinning (fillasses); ‘folle jeunesce’ (foolish youth) kept her more interested in play than in study; and upon her marriage she was occupied with childbearing and caring for a household.51 It was therefore not so incidental that after her husband’s death Christine should describe her changed circumstances as a transformation where Fortune caused her to become a man and taught her the trade. Cerquiglini-Toulet suggests that in this way she becomes the son her father wished for.52 As a man, Christine could truly begin to profit from her father’s riches and follow his example, taking up his work but in her own way.

Yet, as we have noted, Christine was undeniably conscious of her unusual position as a woman writer. Catherine Attwood and Mary Anne Case, among others, have shown that Christine used this position in strategic ways, highlighting the fact that she alone could write as she chose and about her experiences.53 The numerous references in her poetry and other works to her solitude both as a widow and as a female writer and scholar underline her originality (singularité), presenting her as the only person who could express certain ideas and certain experiences.54 The first lines of the Mutacion de fortune are a case in point, for Christine explains that no man (and likely no woman), no matter how learned, could possibly write what she wishes to:55

(How will it be possible for me, simple and of small understanding, to express adequately that which cannot be well expressed or well understood? No, no matter how much learning a man might have, he could not fully describe what I would wish to write.)56

Although she describes herself unassumingly as simple and ‘peu sensible’, only Christine is able to write what she herself has experienced as a result of the vagaries of Fortune. In fact, by virtue of her experience, she views herself as extremely well qualified to speak of Fortune, and even as having a privileged relationship with this figure.57 Christine thus plays with the humility topos: although she is ‘just a simple woman’, she too has something useful to offer through her life experience, something that no one else can write.58

Even when describing the act of writing, Christine draws attention to those experiences in her life that are unique to women. Although she associates the work of the scholar and writer with men, Christine, like her contemporaries, sees the work of writing as one that generates or gives birth to ideas.59 This is particularly evident in the Advision where Christine juxtaposes masculine and feminine metaphors for writing.60 In this text, Nature first exhorts Christine to use the forge, ‘Prens les outilz et fier sur l’enclume’ (Take the tools and strike the anvil) in order to create pleasing things (delictables) out of the durable material Nature provides. She then urges Christine to envisage the pains of writing as that of childbirth: Christine will bring forth volumes from her memory, birthing them in spite of the ‘labour et traveil’ (pain and labour); then, again like a mother, she will forget the pains as she hears the voice of her volumes for the first time.61 Although both metaphors are employed by earlier authors, Christine’s description of writing as being like the pains of childbirth extends the generative metaphor and carries the weight of experience behind it.62 This serves to make the work of writing Christine’s own, to translate the act into terms that are specific to Christine as a female writer while at the same time highlighting the value and worth of women’s experience.

Through writing her own and other women’s experience into her books, Christine transforms the role of the writer, making it conform to her own existence while at the same time legitimising the expression of that existence. Female experience, Christine’s in particular, is important and needs to be articulated, in part because it has much to teach. Christine is quite clear on this point in the prologue to the Livre du chemin de lonc estude (1402–03). She describes herself as an unworthy woman (indigne) and sets herself, as Walters notes, below her noble patron.63 Nonetheless, she insists that from ‘simple personne / peut bien venir vraye raison et bonne’ (a simple person, true and good reason may well come).64 Christine’s juxtaposition of the humility topos with the worth of her words again justifies her work as a writer. Similarly, as Hult suggests, her use of the humility topos in the Epistres du debat sus le Rommant de la Rose enabled Christine to ‘establish a dialogue with her interlocutors from a feminine perspective’, in some sense pitting her experience as a woman against the formal clerkly training received by her learned adversaries.65

Yet this defence of her work and of her worth as a woman writer, is grounded in sound theology. The use of the humility topos is intended to recall the Virgin Mary, the humble handmaiden who bore the Word in the form of the incarnated Christ. Not surprisingly, it appears in the work of other medieval women writers. As Newman argues in her discussion of Hildegard of Bingen, it ‘typified … a central paradox of Christianity: all who humble themselves will be exalted’.66 Christine’s extensive use of this theme helps link her work to the Virgin, thereby evoking a female figure who is associated with Wisdom and with literacy.67 In creating this association, Christine safeguards her work against critics who would reject it solely on the basis of her gender. Like the Virgin herself, Christine is a humble handmaid who—as courtly writer—can also be inspired by Holy Wisdom to serve as messenger to the French court through the words she writes.68

Christine considers it her duty to transmit her wisdom to others. Yet, her work encompasses the responsibilities incumbent upon her dual roles as scholar and as woman. For Christine, women had an obligation to teach by moral and by example and to inspire others through their virtue. This is perhaps most clearly expressed in the Livre des trois vertus (1405) composed for Marguerite of Nevers, the bride of the dauphin, Louis of Guyenne. Christine details the responsibilities of the high-born lady, saying that such a lady should surpass all others in ‘bonté, sagece, meurs, condicions et manieres’ (good prudence, moral standards, conduct, and manners) and serve as a model (exemplaire) for other women.69 While this passage refers specifically to the high-born lady, Christine is careful to note at the beginning of both Books II and III that much of the advice she provides is applicable to all women, regardless of their rank.70 Moreover, through virtuous conduct and goodness, women may serve as examples and inspiration to men: the example Christine provides in the Cité des dames of Blanche of Castile is a case in point. Blanche’s ‘tres grant savoir, prudence, vertus et bonté’ (great learning, prudence, virtue, and goodness) as well as her ‘sages paroles’ (wise words) inspire Thibault of Champagne to cease his attacks against Saint Louis and even to fall in love with Blanche herself.71

Through the act of writing, Christine set herself up as a model for others. Her works—in which she herself is often the example or the messenger—exhort others to a right life of honour and virtue and are themselves ‘good works’ that are both example and execution of that example. This was clearly a conscious choice, one which she articulates in the prayer at the end of the Livre des trois vertus. This prayer, which Christine hopes women will say in her memory, emphasises her role in the transmission of wisdom. She asks them to pray that she may be granted knowledge (sapience) and true wisdom (vraye sapience) such that she may use it in the noble labour of study (noble labour d’estude) for the ‘exaltation of virtue in good examples to every human being’ (l’exaulcement et eslevacion de vertus en bons exemples a toute humaine creature).72 In this way, she portrays herself as practising the very virtues she promotes in an effort to bring wisdom to all humanity. Yet it is the very nature of Christine’s experience in the world and her knowledge of the bottom side of Fortune’s wheel that form and shape her notion of what it means to be a writer and enable her to mould the work of the writer to fit her own situation. In this way, while she claims to have been transformed by Fortune into a man, Christine’s notion of her duty as a female writer results in large part from her understanding of women’s obligations to the world they inhabit. It is only as a writing woman that she may become a Voice of Wisdom, serving as divinely inspired intermediary between her adopted country and Holy Wisdom.

The wisdom of Christine

As a scholar, Christine models her work on her father’s example, regarding it as a calling to offer wise counsel in an effort to better the world around her. As she notes in the Livre des trois vertus, she perceives wisdom as a means to salvation and a closer relationship with God.73 She views it as her duty to share this gift through her writings and accomplished this on a number of different levels.74 She provides spiritual and practical advice to teach young people in works such as the Enseignemens (c. 1398) (commonly known as the Enseignemens moraulx), the Proverbes moraulx (1405), the Epistre Othea (c. 1400), and the Livre des trois vertus.75 Similarly, the Livre du corps de policie takes the form of a mirror of princes. Still other works, such as the Livre du chemin de lonc estude and the Advision Cristine, contain her political advice and commentary on France’s problems. Throughout, Christine offers her wise words and her experience to others.

As we have seen, the notion of a woman as a bearer of Wisdom is an important trope. In examining Christine’s role as a Voice of Wisdom who offers her experience and knowledge in the service of her adopted country, it is essential to consider both Christine’s name, and her relationship with her patron, Ysabel of Bavaria. The name Christine is the feminine form of Christ. Christine herself brings attention to this in the Mutacion de fortune:

(In order for me to be correctly named, just add the letters I, N, E, to the name of the most perfect man who ever lived; no other letter is necessary.)76

The emphasis on writing is critical, for the representation of her name in the manuscripts is often created with the Chi and the Rho plus ‘ine’: ‘xpine’.77 While orally and aurally, her name represents a feminisation of Christ, the use of the Chi and the Rho forges symbolic connotations. The figure of Wisdom appears both as female (Old Testament Wisdom) or occasionally as male (Christ-as-Logos).78 Hence the conjunction of male and female here, of Christ and Christine, through the Word, brings out the Wisdom trope and authorises Christine’s construction of herself as a Voice of Holy Wisdom.

Yet to function well in such a role, Christine could not act alone. To transmit her advice and counsel, Christine worked through female agency, focusing on women as intercessors who were capable of influencing men and their actions for the greater good.79 One of the best examples of this is her work for her patron Ysabel of Bavaria, queen of France. Ysabel had the difficult task of being queen during the civil unrest and political strife occasioned by the periodic madness of her husband, Charles VI.80 His frequent inability to rule required her to act in the capacity of regent, serve as peacemaker between rival factions, and look out for the interests and education of the royal children, most importantly the young dauphin.

The parallels between Christine and Ysabel are fascinating for a consideration of women and work. As Walters observes, they shared a number of similar life experiences. They were born outside France to Italian mothers. Their daughters, both named Marie, entered the abbey of Saint-Louis-de Poissy in 1398. Each lost a husband, one to death, the other to mental illness. They also both embraced a common goal in furthering the well-being of France.81 Moreover, in order for Christine to achieve her purpose as a writer, and serve as a vehicle and a Voice for the Holy Wisdom that could help the kingdom of France, she needed not just a patron, but an association or partnership with a temporal authority, a figure who could aid the dissemination of that wisdom and serve as intercessor.82 The queen was ideally situated to take on such a role: as the ‘feminine face of power’ she provided the perfect counterpart to Christine’s construction of herself as the Voice of Wisdom.83

Ysabel was important not just as Christine’s benefactress, but also as the recipient of many of her works and as a subject depicted within them. For example, Christine’s depiction of the ‘Wise Princess’ in the first book of the Livre des trois vertus ‘closely echoes [Ysabel’s] situation and illuminates the difficulties the queen faced’.84 In this text and elsewhere, Christine appeared to consider it her duty to use her writing as a means to support the queen for the betterment of France.85 The picture that emerges is of a working relationship, of patronage on the part of the queen and a kind of advisory and supportive role on Christine’s part.86 In her work with and for the queen, Christine assumes her father’s vocation, but in a feminine reflection of his role: where he was an advisor to King Charles V, she became an advisor to Ysabel of Bavaria.87

The suggestion of this supportive role can be seen quite early on in Christine’s career with her composition of MS Chantilly 492–493.88 Christine probably presented the major part of it to Ysabel in 1399 or shortly thereafter.89 The presentation of a manuscript to the queen carried significance beyond that of a personal gift: manuscripts were often read aloud in the houses of the aristocracy and their contents were heard and discussed by the entourage surrounding such figures as the queen and other nobles.90 Consequently the gift of a manuscript reached a much larger public than the recipient alone. The contents of MS Chantilly 492 offer a strong message about female authority and female teachings. This was particularly relevant, for at this time it was becoming increasingly clear that the king was never going to overcome his madness. Hence the problem of regency—and particularly the queen’s ability to act as regent—was a chief concern.91

MS Chantilly 492 contains a number of works which develop the idea of female authority and sanction the transmission of wisdom from a female figure. For example, the Epistre Othea (c. 1400) is specifically oriented towards the education of a young prince (Hector) by a female figure (the goddess Othéa) and appears ‘designed to exemplify the wisdom of women’.92 Accordingly, it furnishes an excellent argument on the one hand for Ysabel’s suitability as guide, counsellor, and teacher to the dauphin, and on the other for the wisdom transmitted by a female writer. Another work included in the manuscript is the first set of letters from the Debate over the Roman de la Rose. These are accompanied by a letter of dedication and explanation addressed to the queen (1402).93 This letter introduces the Debate and submits it to the queen as an arbiter of higher authority. Christine asks Ysabel to approve her arguments in support of women and to provide ‘saige et benigne correction’ (wise and gentle correction).94 Accordingly Christine attributes both authority and wisdom to Ysabel. Both as woman and as ruling queen, Ysabel has the experience and authority to judge the Debate and Christine’s role within it as women’s defender. In a last example, this manuscript also contains the Enseignemens, moral teachings that Christine composed for her son. By offering these to the queen, Christine emphasises Ysabel’s role as Mother Queen of France, providing her with material and wisdom for the education of her own children, the future kings of France.95 At the same time, she also reinforces her own authority as a writer and Voice of Wisdom.

Yet nowhere is Christine’s support of the queen as a source of wisdom more evident than in the ways she links Ysabel’s symbolic role to that of the Virgin Mary. In many of her works, Christine pairs Ysabel and Mary, developing the parallels between Heavenly Queen and her earthly counterpart.96 This relationship is of particular consequence for the queen’s suitability as regent: Christine uses references to the Virgin Mary as the ‘ultimate coregent’ in support of the queen’s authority.97 Adams, who rereads the Cité des dames as an argument for coregency, suggests that Christine’s use of the Virgin in this work allows her to marry both terrestrial and spiritual authority through female agency. The Cité des dames both ‘begins and ends with the Virgin Mary, a regent, a woman who ruled on behalf of her son’.98 The fact that Christine then places Ysabel at the ‘head of the good and generous princesses of France’ is significant for it situates Ysabel in the leading position, ‘first among female partners of the realm’.99 She becomes Mary’s counterpart on earth, a temporal authority, first among women in the contemporary terrestrial sphere.100

The Epistre a la Royne, also composed in 1405, develops further parallels between the wisdom of Ysabel and Mary. Where Mary is the Mother of all Christianity (mere de toute christienté), Ysabel, as a wise and good queen (saige et bonne royne), is her worldly equivalent, serving as the mother and comforter (mere et conffortarresse) of her subjects.101 It is she who can mediate better than any other on their behalf.102 Motherhood also plays an essential role here, for while Mary is the mother of Christ and hence of all Christianity, Ysabel is mother of the future rulers of France and by extension mother of all France. By drawing these parallels between Ysabel and Mary, Christine gives prominence to Ysabel’s symbolic role, delineating and describing it for her audience. While the Epistre a la Royne is usually interpreted as Christine’s urgent call to a reticent queen to act and mediate for peace, Adams argues that it can be read as a reminder directed to Christine’s readers ‘of the precedent for queenly intervention’.103 The letter is thus intended to educate this public and enable them to push the warring factions, in this case the dukes of Orleans and Burgundy, to accept Ysabel as mediator and peacemaker.104 It teaches them about the queen’s role and ‘bolster[s] support’ for female regency.105 Yet it also serves as a way to join both spiritual and temporal authority, constructing Ysabel herself as an allegorical figure, the Mother Queen of France.

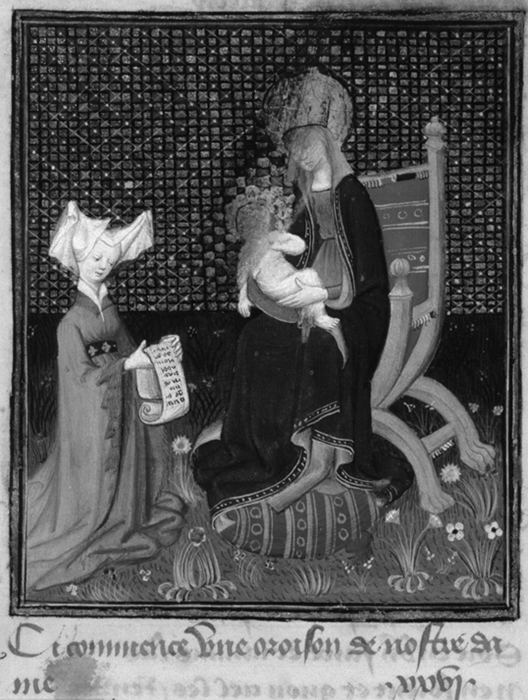

Christine brings out this alliance between the female figure and Wisdom in her manuscripts both visually and textually. One of the best examples of this is in MS Harley 4431. This manuscript, the last compilation of Christine’s collected works to be published under her direction, was also presented to the queen, most likely as a New Year gift in 1414.106 Famous for its magnificent opening miniature which shows Christine’s presentation of her book to the queen (fol. 3r), the manuscript takes on the theme of the book as a gift of wisdom.107 Through textual and iconographic associations, many of the works contained within it show women, including Christine herself, as the bearers of Holy Wisdom. Of particular interest is the miniature heading the Oroison de Nostre Dame (c. 1402), a prayer to the Virgin that implores Mary’s aid both for the royal family and for France and invokes the Virgin as a source of wisdom.108

The miniature, seen in Figure 5.1, shows the Virgin sitting with the Christ-child on her lap in a red-upholstered chair with lion’s paw feet; Christine kneels to the Virgin’s left, holding a written page in her hands as the visible representation of the prayer she offers. The image emphasises Mary’s association with Holy Wisdom through colour symbolism and iconography. Wisdom was seen as part of a ‘liturgical and exegetical tradition poised uneasily between Christ and Mary, affiliating Wisdom now with one and now with the other’, and hence providing for a ‘feminization of Christ and the divinization of Mary’.109 Accordingly, the combination of the colours blue, which was associated with the Virgin from the twelfth century, and red, which recalled the ‘blood spilled by and for Christ, and hence the passion, martyrdom, sacrifice and divine love’, reflect the dual nature of Holy Wisdom and remind the viewer of the Virgin’s connection to this figure.110 The connection to Wisdom is also reinforced by the lion’s paw feet on the chair, which are an allusion to the Throne of Solomon. This image creates a series of parallels, developing a metaphor that connects Christine’s gift to the Virgin and Child. Just as Mary, in giving birth to Christ (the Word), gives the gift of salvation to the world, Christine gives birth to her work (her prayer and the manuscript in which it is contained) for the salvation of France.111 In this, we come full circle: Christine, in her role as courtly poet—or now as poète curiale—serves as a unique intermediary between her patron, Ysabel, and the Holy Wisdom of the Virgin.112 As Wisdom’s Voice, her gift of her words and her book to the queen mirrors that given by the Virgin herself.113 At the same time, as can be seen in the majesty of the book presentation scene at the beginning of the manuscript, Christine’s gift also highlights Ysabel’s role as model in her own right of female authority in whom Wisdom must reside.

Thus Christine, whose notion of what it means to work as a woman-scholar requires her to offer her knowledge to others and for the betterment of France, constructs a network of associations through her writing as well as partnerships to accomplish these goals. On the one hand, she calls attention to her name, linking herself to Christ-as-Wisdom as a way of authorising her own role in wisdom’s transmission. Similarly, in her association with Ysabel of Bavaria, she also draws attention to symbolic aspects, linking Ysabel to Mary. The figure of the Virgin Mary serves to link temporal and spiritual realms, making possible the birth of Christ-as-Logos and thus the transmission of Holy Wisdom through Christine. The theme of motherhood also ties all three together: Mary incarnates the Word; Ysabel brings into the world the future leaders of France. Christine, who equates writing with giving birth, engenders wisdom in her writing and even a Wisdom text in the Enseignemens she composes for her son. Her construction of these associations allows her to deflect contemporary ambivalence about women as rulers and as writers, anchoring her work in the most orthodox of doctrines.

Conclusion

Christine de Pizan’s decision to make a living as a writer was extraordinary for a woman in the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries and her work provides a fascinating window into her experiences. As a woman working in what was primarily a man’s field, Christine suggests that Fortune transformed her into a man. Nevertheless, she reworks the male authorial role to suit herself and her abilities, making her female gender a fundamental part of her uniqueness as a writer. Christine herself becomes an essential component of her writing, both as author and as written example for others to follow. Even within the context of the Epistres du debat sus le Rommant de la Rose Christine stands as the lone female voice against the almost universal condemnation of women found in the Rose and condoned by her clerkly adversaries.

In the unusual circumstances of the power vacuum created by the madness of Charles VI, Christine plays a particularly important role. She follows her scholar father’s model, becoming an advisor to princes; yet she expands this model to incorporate both genders, a necessity in a time when the normal power structure was not functional.114 In becoming an advisor to the queen, she underlines the importance of the role Ysabel needed to play and educates her audience about female authority. She does this in part by emphasising the common experience of women and by depicting women—particularly Mary, Ysabel, and herself—as figures of Wisdom. Through visual and textual associations, she presents all three allegorically: Mary as Heavenly paradigm for female authority, Ysabel as Mother Queen and earthly representative of that authority, and Christine herself as the Voice of Wisdom who serves as intermediary between the courtly and heavenly realms. Christine, as writer and as Voice of Wisdom, manifests her love for her adopted country and demonstrates the value both of women’s work and women’s wisdom.

Notes

1Christine de Pizan, Le livre de la mutacion de fortune, ed. Suzanne Solente, 4 vols. (Paris: Picard, 1959–66), 1:53 (v. 1393).

2Christine de Pizan, Le livre de l’advision Cristine, ed. Christine Reno and Liliane Dulac (Paris: Champion, 2001), 100–01 (III.6); Charity Cannon Willard, Christine de Pizan: Her Life and Works (New York: Persea Books, 1984), 39–40.

3Pizan, Mutacion de fortune, 1: 12 (vv. 141–43). Pizan, Mutacion de fortune, 1:53 (vv. 1388–94).

4Pizan, Advision, 111 (III.11). She also notes the effect of novelty in her letter to Pierre Col during the Debate of the Roman de la Rose on those who wanted her works: they were ‘esmerveillés de mon labour, non pour grandeur qui y fait mais pour le cas nouvel qui n’est accoustumé’ (astonished by my labour, not for any greatness to be found there, but because of its novelty, which is out of the ordinary). ‘A maistre Pierre Col, secretaire du roy nostre sire’, in Christine de Pisan, Jean Gerson, Jean de Montreuil, Gontier et Pierre Col, Le Débat sur le Roman de la Rose, ed. Eric Hicks (Genève: Slatkine Reprints, 1996), 148. English translation from Christine de Pizan, Debate of the ‘Romance of the Rose’, trans. and ed. David F. Hult (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010), 191.

5See Charity Cannon Willard, ‘Christine de Pizan as Teacher’, Romance Languages Annual 3 (1992). See also Roberta Krueger, ‘Christine’s Anxious Lessons: Gender, Morality and the Social Order from the Enseignements to the Avision’, in Christine de Pizan and the Categories of Difference, ed. Marilynn Desmond (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1998); as well as Astrik L. Gabriel, ‘The Educational Ideas of Christine De Pisan’, Journal of the History of Ideas 16 (1955).

6Cf. Jacqueline Cerquiglini-Toulet, ‘Fondements et fondations de l’écriture chez Christine de Pizan. Scènes de lecture et scènes d’incarnation’, in The City of Scholars. New Approaches to Christine de Pizan, ed. Margarete Zimmermann and Dina De Rentiis (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1994), 80–82, 84.

7Pizan, Advision, 111 (III.10); Charity C. Willard, ‘A Fifteenth-Century View of Women’s Role in Medieval Society: Christine de Pizan’s Livre des Trois Vertus’, in The Role of Woman in the Middle Ages, ed. Rosmarie T. Morewedge (Albany: State University of New York, 1975), 94.

8Barbara Hanawalt, ‘Introduction’, in Women and Work in Preindustrial Europe, ed. Barbara Hanawalt (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1986), x.

9Pizan, Advision, 108 (III.8); Christine’s Vision, trans. Glenda McLeod (New York: Garland Pub., 1993), 117.

10Willard, Life and Works, 203–05. Christine de Pizan, La città delle dame, ed. Earl Jeffrey Richards, trans. Patrizia Caraffi (Milan: Luni, 1998), 316 (II.36).

11Pizan, Advision, 107–08 (III.8).

12Hanawalt, ‘Introduction’, xi. Simone Roux, Christine de Pizan: Femme de tête, dame de cœur (Paris: Payot, 2006), 65.

13Pizan, Advision, 98 (III.4), 100 (III.6).

14Willard, Life and Works, 39–40; Nicolae Iorga, Philippe de Mézières, 1327–1405 (London: Variorum Reprints, 1973), 510 n. 5.

15Roux, Christine de Pizan, 67.

16Roux, Christine de Pizan, 67.

17Willard, ‘A Fifteenth-Century View’, 94.

18Gilbert Ouy and Christine Reno, ‘Identification des autographes de Christine de Pizan’, Scriptorium 34 (1980): 226.

19Ouy and Reno, ‘Autographes’, 222. See also Gilbert Ouy, Christine Reno, and Inès Villela-Petit, Album Christine de Pizan (Turnhout: Brepols, 2012), 25.

20Glenda McLeod, ‘Introduction’, Pizan, Christine’s Vision, xlv.

21Bronislaw Geremek, Le salariat dans l’artisanat parisien aux XIIIe–XVe siècles: étude sur le marché de la main-d’œuvre au Moyen Âge (Paris: Mouton & Co, 1968); Richard H. Rouse and Mary A. Rouse, Manuscripts and their Makers: Commercial Book Producers in Medieval Paris, 1200–1500, 2 vols. (Turnhout: Harvey Miller, 2000), 1:237.

22Willard, ‘A Fifteenth-Century View’, 95.

23Willard, ‘A Fifteenth-Century View’, 94–95.

24Willard, ‘A Fifteenth-Century View’, 94.

25On the spelling of the queen’s name, see Lori Walters, ‘The Book as a Gift of Wisdom: The Chemin de lonc estude in the Queen’s Manuscript, London, British Library, Harley 4431’, Digital Philology 5 (2016): 229 n. 7. I am very grateful for the author’s generosity in sharing an early version of this article with me.

26‘La Premiere epistre, a la royne de France’ in Débat, 5. Martha Breckenridge, ‘Christine de Pizan’s “Livre d’epitre d’Othea a Hector” at the Intersection of Image and Text’ (Ph.D. diss., University of Kansas, 2008), 29. Cf. also Roux, Christine de Pizan, 92; Andrea Tarnowski, ‘Introduction’, in Christine de Pizan, Le chemin de longue étude, trans. and ed. Andrea Tarnowski (Paris: Librairie générale française, 2000), 12; Eric Hicks and Thérèse Moreau, ‘L’Epistre à la Reine de Christine de Pizan (1405)’, Clio. Histoire, femmes et sociétés 5 (1997): n. 1. On the role of the chamberiere, see Walters, ‘Book’, 229 n. 12. See also Patrick M. de Winter, La bibliothèque de Philippe le Hardi, duc de Bourgogne: 1364–1404. Étude sur les manuscrits à peintures d’une collection princière à l’époque du style gothique international (Paris: Centre national de la recherche scientifique, 1985), 14, 19.

27Olivier Delsaux, et al., ‘Le premier recueil de la Reine’, in Christine de Pizan et son époque, ed. Danielle Buschinger (Amiens: Centre d’études médiévales, Université de Picardie-Jules Verne, 2012), 49–50.

28Gilbert Ouy, Letter to Olivier Delsaux, quoted in Delsaux, et al., ‘Le premier recueil’, 51–52; Ouy, Reno, and Villela-Petit, Album, 22–38, 739–40.

29Ouy, Reno, and Villela-Petit, Album, 173, 173–85.

30Pizan, Advision, 111 (III.10).

31Pizan, Advision, 111 (III.10). English translations are mine unless otherwise noted.

32Pizan, Advision, 111 (III.10).

33Ouy and Reno, ‘Autographes’, 222.

34Pizan, Advision, 111 (III.10). Cf. James Laidlaw, ‘Christine de Pizan: A Publisher’s Progress’, Modern Language Review 82 (1987): 37.

35Ouy and Reno, ‘Autographes’, 222.

36Pizan, La città delle dame, 192 (I.41). English translation from Christine de Pizan, The Book of the City of Ladies, trans. Earl Jeffrey Richards, rev. edn. (New York: Persea Books, 1998), 85. Anastaise is known to us only through Christine’s references to her in the Cité des dames.

37La città delle dame, 192 (I.41).

38See for example, the family of Nicolas d’Etampes. Rouse and Rouse, Manuscripts and their Makers, 1:116–19.

39Rouse and Rouse, Manuscripts and their Makers, 1:236–37.

40Rouse and Rouse, Manuscripts and their Makers, 1:237.

41Pizan, Advision, 111 (III.11).

42Pizan, Mutacion de fortune, 1:16 (vv. 260–84).

43‘lesquelz de leur grace comme princes benignes et tres humains les virent voulentiers et receurent a joie—et plus, comme je tiens, pour la chose non usagee que femme escripse, comme pieça n’avenist, que pour la digneté que y ssoit’. (These they willingly saw and by their grace joyfully received like kind and gentle princes, and more I think for the novelty of a woman who could write (since that had not occurred for quite some time) than for any worth there might be in them.) Pizan, Advision, 111 (III.11). English translation from Pizan, Christine’s Vision, 120.

44Christine does not name these critics directly, choosing instead to designate them as ‘aucuns’ (certain people). Pizan, Advision, 88 (II.22).

45Pizan, Advision, 88 (II.22).

46Cerquiglini-Toulet, ‘Fondements’, 82–83.

47Ilse Paakkinen, ‘The Metaphysics of Gender in Christine de Pizan’s Thought’, in Gender in Late Medieval and Early Modern Europe, ed. Marianna G. Muravyeva and Raisa Maria Toivo (New York: Routledge, 2013), 45.

48Susan Schibanoff, ‘Taking the Gold out of Egypt: The Art of Reading as a Woman’, in Gender and Reading: Essays on Readers, Texts, and Contexts, ed. Elizabeth A. Flynn and Patrocinio P. Schweickart (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986), 99.

49Pizan, Mutacion de fortune, 1:14 (vv. 211–20).

50Pizan, Mutacion de Fortune, 1:21 (vv. 413–19).

51Pizan, La città delle dame, 316 (II.36). Pizan, Advision, 108 (III.8). Pizan, Mutacion de fortune, 1:46 (vv. 1165–66).

52Jacqueline Cerquiglini, ‘The Stranger’, in The Selected Writings of Christine de Pizan: New Translations, Criticism, ed. Renate Blumenfeld-Kosinski, trans. Renate Blumenfeld-Kosinski and Kevin Brownlee (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1997), 270.

53Catherine Attwood, ‘Fortune et le “moi” écrivant à la fin du Moyen Âge: autour de la Mutacion de fortune de Christine de Pizan’, Nottingham French Studies 38 (1999): 26; Mary Anne Case, ‘Christine de Pizan and the Authority of Experience’, in Christine de Pizan and the Categories of Difference, ed. Marilynn Desmond (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1998), 71, 84.

54Attwood, ‘Fortune et le “moi”’, 26.

55Attwood, ‘Fortune et le “moi”’, 30.

56Pizan, Mutacion de fortune, 1:7 (vv. 1–8). English translation from The Selected Writings of Christine de Pizan, ed. Blumenfeld-Kosinski, 89. Emphasis mine.

57See Attwood, ‘Fortune et le “moi”’, 26.

58Cf. Cerquiglini-Toulet, ‘Fondements’, 80–82, 84.

59Jacqueline Cerquiglini, ‘Introduction’, in Christine de Pizan: Cent ballades d’amant et de dame, ed. Jacqueline Cerquiglini (Paris: Union générale d’éditions, 1982), 14.

60Cerquiglini, ‘Introduction’, 14.

61Pizan, Advision, 110 (III.10).

62Cerquiglini, ‘Introduction’, 14.

63Walters, ‘Book’, 231.

64Christine de Pizan, Le chemin de longue étude, trans. and ed. Tarnowski, 88–90 (vv. 28, 53–54). English translation mine.

65Marilynn Desmond, ‘The Querelle de la Rose and the Ethics of Reading’, in Christine de Pizan: A Casebook, ed. Barbara K. Altman and Deborah L. McGrady (New York: Routledge, 2003), 168; David F. Hult, ‘Introduction’, in Debate of the ‘Romance of the Rose’, trans. and ed. Hult, 2–3.

66Barbara Newman, Sister of Wisdom: St. Hildegard’s Theology of the Feminine (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), 2–3.

67Cf. Georgiana Donavin, Scribit Mater: Mary and the Language Arts in the Literature of Medieval England (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 2012), 4–5; Laura Saetveit Miles, ‘The Origins and Development of the Virgin Mary’s Book at the Annunciation’, Speculum 89 (2014): 668.

68Cf. Gérard Gros, ‘“Mon oroison entens…”. Étude sur les trois opuscules pieux de Christine de Pizan’, Bien dire et bien aprandre 8 (1990): 101.

69Christine de Pizan, Le livre des trois vertus. Édition critique, ed. Charity Cannon Willard and Eric Hicks, (Paris: H. Champion, 1989), 111 (I.27); Christine de Pizan, The Treasure of the City of Ladies or the Book of the Three Virtues, trans. Sarah Lawson (London: Penguin, 1985), 99.

70Pizan, Livre des trois vertus, 171 (III.1).

71Pizan, La città delle dame, 412–14 (II.65); Pizan, City of Ladies, 207–08.

72Pizan, Livre des trois vertus, 225–26 (Fin); Pizan, Treasure of the City of Ladies, 180. Emphasis mine.

73Pizan, Livre des trois vertus, 11 (I.2).

74Walters argues that Christine offers Harley 4431 as a gift of wisdom to the queen. Walters, ‘Book’, 229.

75Christine never calls the Enseignemens the ‘Enseignemens moraulx’, but names it the ‘notables moraulx’ or the ‘enseignemens’. I follow her final appellation of it, found in Harley 4431, fol. 261v. Ellen Thorington, ‘Figures de la Sagesse et de l’autorité féminine. L’exemple des Enseignemens de Christine de Pizan’, Le Moyen Français 78–79 (2016): 223 n. 2.

76Pizan, Mutacion de fortune, 1:20 (vv. 374–78); Christine de Pizan, ‘The Book of Fortune’s Transformation’, in The Selected Writings of Christine de Pizan, ed. Blumenfeld-Kosinski, trans. Blumenfeld-Kosinski and Brownlee, 94.

77Lori Walters, ‘Signatures and Anagrams in the Queen’s Manuscript (London, British Library, Harley MS 4431)’, (2012). Accessed August 17, 2017. www.pizan.lib.ed.ac.uk/waltersanagrams.html. See also Cerquiglini, ‘The Stranger’, 274.

78Joan M. Ferrante, Woman as Image in Medieval Literature from the Twelfth Century to Dante (Durham, NC: Labyrinth Press, 1985), 4.

79Christine herself often plays a dual role of both author and character within works such as the Chemin de longue étude. As writer she is responsible for the transmission of the words that contain the message borne by Christine-the-character to the French court. See Walters, ‘Book’, 231.

80Cf. R.C. Famiglietti, Royal Intrigue: Crisis at the Court of Charles VI, 1392–1420 (New York: AMS Press, 1986), 7.

81Walters, ‘Book’, 232.

82On the idea of female-female partnership, see Walters, ‘Book’, 233–35, 237.

83Tracy Adams, ‘Christine de Pizan, Isabeau of Bavaria, and Female Regency’, French Historical Studies 32 (2009): 26.

84Adams, ‘Regency’, 4, 27; Tracy Adams, The Life and Afterlife of Isabeau of Bavaria (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010), 80–83. Cf. Pizan, Livre des trois vertus, 7–120 (I).

85Adams, ‘Regency’, 3.

86Walters, ‘Book’, 237.

87Walters, ‘Book’, 237.

88The first volume of the manuscript dates to 1399–1402; the second volume, MS 493, to between 1403 and c. 1405. Ouy, Reno, and Villela-Petit, Album, 190, 205.

89Delsaux, et al., ‘Le premier recueil’, 51–52.

90Adams, ‘Regency’, 25. See also Joyce Coleman, Public Reading and the Reading Public in Late Medieval England and France (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 95–97; Pizan, Livre des trois vertus, 50 (I.12).

91Adams, ‘Regency’, 9–17. See also Adams, Life.

92Bonnie A. Birk, Christine de Pizan and Biblical Wisdom: A Feminist-Theological Point of View (Milwaukee, WI: Marquette University Press, 2005), 65.

93Pizan, Debate of the ‘Romance of the Rose’, 99 n. 129.

94Débat, 6, l. 42.

95Cf. Ellen M. Thorington, ‘Le “lait de sagesse”: les Enseignemens moraux de Christine de Pizan comme legs civique’, in Le legs des pères et le lait des mères ou comment se raconte le genre dans la parenté du Moyen-Âge au XXIème siècle, ed. Isabelle Ortega and Marc-Jean Filaire-Ramos (Turnhout: Brepols, 2014).

96Walters, ‘Book’, 232.

97Adams, ‘Regency’, 3.

98Adams, ‘Regency’, 26.

99Adams, ‘Regency’, 26.

100Cf. Adams’ discussion of the Goldenes Rössl. Adams, Life, 110–11; see also 104–12.

101Christine de Pizan, The ‘Epistle of the Prison of Human Life’, with ‘An Epistle to the Queen of France’ and ‘Lament on the Evils of the Civil War’, trans. and ed. Josette Wisman (New York: Garland, 1984), 78.

102Adams, ‘Regency’, 30.

103Adams, Life, 189; Adams, ‘Regency’.

104Adams, Life, 189; Adams, ‘Regency’.

105Adams, ‘Regency’, 24–25.

106Ouy, Reno, and Villela-Petit, Album, 319; James Laidlaw, ‘The Date of the Queen’s MS (London, British Library, Harley MS 4431)’, (2005): 7. Accessed August 17, 2017. www.pizan.lib.ed.ac.uk/harley4431date.pdf. On the gift of books and manuscripts for étrennes, see Brigitte Buettner, ‘Past Presents: New Year’s Gifts at the Valois Courts, ca. 1400’, The Art Bulletin 83 (2001): 604.

107London, British Library, Harley MS 4431. Images of the manuscript are available online: James Laidlaw, ‘Christine de Pizan: The Making of the Queen’s Manuscript (London, British Library, Harley MS 4431)’, Edinburgh University Library. Accessed August 17, 2017. www.pizan.lib.ed.ac.uk/. For the manuscript as a gift of wisdom, see Walters, ‘Book’, 229.

108Cf. Thorington, ‘Le “lait de sagesse”’, 56–60.

109Barbara Newman, God and the Goddesses: Vision, Poetry, and Belief in the Middle Ages (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002), 193.

110Michel Pastoureau, Blue: The History of a Color, trans. Markus I. Cruse (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001), 37, 50. See the representations of Wisdom in New York, Morgan Library and Museum, MS M. 791, fol. 288r, and New York, Morgan Library and Museum, MS M. 392, fol. 239r.

111Thorington, ‘Lait’, 60. Walters, ‘Book’, 234–35.

112Gros, ‘Oroison’, 101.

113Walters, ‘Book’, 232.

114Walters, ‘Book’, 233.

Select bibliography

Adams, Tracy. ‘Christine de Pizan, Isabeau of Bavaria, and Female Regency’. French Historical Studies 32 (2009): 1–32.

——— The Life and Afterlife of Isabeau of Bavaria. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010.

Attwood, Catherine. ‘Fortune et le “moi” écrivant à la fin du Moyen Âge: autour de la Mutacion de fortune de Christine de Pizan’. Nottingham French Studies 38 (1999): 25–43.

Case, Mary Anne C. ‘Christine de Pizan and the Authority of Experience’. In Christine de Pizan and the Categories of Difference, ed. Marilynn Desmond, 71–87. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1998.

Cerquiglini, Jacqueline. ‘Introduction’. In Christine de Pizan: Cent ballades d’amant et de dame, ed. Jacqueline Cerquiglini, xi–xlvi. Paris: Union générale d’éditions, 1982.

Cerquiglini-Toulet, Jacqueline. ‘Fondements et fondations de l’écriture chez Christine de Pizan. Scènes de lecture et scènes d’incarnation’. In The City of Scholars. New Approaches to Christine de Pizan, ed. Margarete Zimmermann and Dina De Rentiis, 79–96. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1994.

Gros, Gérard. ‘“Mon oroison entens …”: Étude sur les trois opuscules pieux de Christine de Pizan’. Bien dire et bien aprandre 8 (1990): 99–112.

Hanawalt, Barbara. ‘Introduction’. In Women and Work in Preindustrial Europe, ed. Barbara Hanawalt, vii–xviii. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1986.

Hult, David F. ‘Introduction’. In Debate of the Romance of the Rose, trans. and ed. David F. Hult, 1–25. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010.

Newman, Barbara. Sister of Wisdom: St. Hildegard’s Theology of the Feminine. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997.

Ouy, Gilbert, and Christine Reno. ‘Identification des autographes de Christine de Pizan’. Scriptorium 34 (1980): 221–38.

Ouy, Gilbert, Christine Reno, and Inès Villela-Petit. Album Christine de Pizan. Turnhout: Brepols, 2012.

Paakkinen, Ilse. ‘The Metaphysics of Gender in Christine de Pizan’s Thought’. In Gender in Late Medieval and Early Modern Europe, ed. Marianna G. Muravyeva and Raisa Maria Toivo, 37–52. New York: Routledge, 2013.

Rouse, Richard H., and Mary A. Rouse. Manuscripts and their Makers: Commercial Book Producers in Medieval Paris, 1200–1500. 2 vols. Turnhout: Harvey Miller, 2000.

Roux, Simone. Christine de Pizan: Femme de tête, dame de cœur. Paris: Payot, 2006.

Thorington, Ellen M. ‘Figures de la Sagesse et de l’autorité féminine. L’exemple des Enseignemens de Christine de Pizan’. Le Moyen Français 78–79 (2016): 223–39.

———‘Le “lait de sagesse”: les Enseignemens moraux de Christine de Pizan comme legs civique’. In Le legs des pères et le lait des mères ou comment se raconte le genre dans la parenté du Moyen Âge au XXIème siècle, ed. Isabelle Ortega and Marc-Jean Filaire-Ramos, 45–63. Turnhout: Brepols, 2014.

Walters, Lori. ‘The Book as a Gift of Wisdom: The Chemin de lonc estude in the Queen’s Manuscript, London, British Library, Harley 4431’. Digital Philology 5 (2016): 228–46.

Willard, Charity C. ‘A Fifteenth-Century View of Women’s Role in Medieval Society: Christine de Pizan’s Livre des Trois Vertus’. In The Role of Woman in the Middle Ages, ed. Rosmarie T. Morewedge, 90–120. Albany: State University of New York, 1975.