Chapter Three

Warren Burger Was Born

Here: Minnesota's

Judicial System

Learning Objectives

- Identify the three levels of court of the Minnesota Judicial Branch

- Describe the budgetary resources devoted to the Minnesota Judicial Branch annually

- Describe the jurisdictions of the Minnesota Court of Appeals and Supreme Court

- Explain the role and function of Minnesota district courts

- Describe judicial selection and election in Minnesota

- Identify agencies responsible for oversight of Minnesota's judicial and legal communities

- Identify the sources of legal education in Minnesota

- Explain the various problem-solving courts in Minnesota

- Describe factors influencing prosecutorial decisions regarding charges and plea bargains

- Articulate the rights of crime victims in Minnesota

As the chapter title suggests, one of Minnesota's judicial claims to fame is the fact that Warren Burger, Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court from 1969 to 1986, came from the state. Burger was born in St. Paul, Minnesota, in 1907. He attended the University of Minnesota prior to law school. He then attended the St. Paul College of Law (the Mitchell Hamline School of Law today) part-time at night, graduating in 1931. In the two decades after graduating, he worked in private practice in the Twin Cities, as well as serving as a part-time faculty member at the St. Paul College of Law (Supreme Court Historical Society, 2015).

Burger was active in Minnesota's Republican Party. He played a leadership role in the successful gubernatorial campaigns of Harold Stassen, as well as Stassen's losing bid to secure the Republican Party's presidential nomination in 1948 and 1952. Burger and the Minnesota delegation to the 1952 Republican National Convention got behind Dwight Eisenhower when it was clear that Stassen wasn't going to win the nomination. Burger delivered to Eisenhower Minnesota's delegates—something for which Eisenhower remained grateful upon being elected President (Biography, 2015).

In 1953, President Eisenhower appointed Burger to be Assistant Attorney General of the United States. He was placed in charge of the Justice Department's Civil Division. In 1955, President Eisenhower appointed Burger to the Circuit Court of Appeals for Washington DC. This appellate court is widely regarded as the most powerful and influential court in the United States short of the U.S. Supreme Court. However, Burger did not have to settle for the second most powerful court. In 1969, President Richard Nixon nominated Burger to be Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court. The Senate confirmed the nomination and he took his seat on the Court in June of 1969—a position he held for 17 years until his retirement in 1986 (Biography, 2015).

As proud as the juridical community in Minnesota is of its favorite son, Chief Justice Burger never served in the judiciary at the state or local level. His career took him from private practice to federal executive service in Washington DC, and from there to the federal judiciary.

Minnesota's Judicial Branch

As with every other state and the federal government, Minnesota's government consists of three branches: the executive branch, led by the governor, a bi-cameral legislature, and the state judiciary. The judicial branch of government includes the Minnesota Supreme Court, the appellate courts, and the district courts, which include specialized courts. The judicial branch also includes the administrative and bureaucratic apparatus to operate the judiciary,

including court administrators and court services personnel. In total, the Minnesota judicial branch employs over 2,500 people and has an annual budget in excess of $300,000,000 (Minnesota Judicial Branch, 2014).

The published mission statement of the Minnesota judicial branch is: “To provide justice through a system that assures equal access for the fair and timely resolution of cases and controversies” (Minnesota Judicial Branch, 2014a, p. 4). Access to justice is a fundamental goal for the judiciary in Minnesota and in every other state. Indeed, in addition to being a central piece of the mission statement, access to justice is the first goal among three key goals in the Minnesota judiciary's strategic plan in FY 2015. The plan states that the judicial branch seeks to deliver to the people of Minnesota a justice system that is “open, affordable, understandable, and provides appropriate levels of service to all users” (Minnesota Judicial Branch, 2014a, p. 5).

The two remaining stated goals for the judiciary include: administering justice for effective results (which is accomplished by adopting processes which enhance outcomes for participants in the system) and bolstering public trust, accountability, and impartiality. Notably, all of these stated goals of the Minnesota judicial branch are focused on citizenry—particularly those who use or become participants in the judicial system. Certainly, access to justice is a laudable end worthy to be pursued in and of itself. However, the 2nd and 3rd goals have more of a consumerist tone. Lofty goals such as finding the truth in conflict, or reducing crime, give way to customer service. Philosophically and politically, Minnesota is known for pragmatism and populism, so perhaps this orientation of the judiciary should come as no surprise.

Table 3.1. Minnesota's Judicial Branch

Minnesota Supreme Court

The court system in Minnesota is established in Article VI of the Minnesota Constitution. Similar to the U.S. Constitution, which establishes the U.S. Supreme Court but leaves the appellate and lower courts to be established by Congress, the Minnesota Constitution only requires that there shall be a Supreme Court; the court of appeals, district courts, and courts inferior to district courts are to be established by the legislature. The Constitution nevertheless anticipates district courts to be established as it speaks to the jurisdiction, number and boundaries of judicial districts and district judges, and qualifications and compensation of district judges. Interestingly, for most of Minnesota's state history (beginning in 1858), there were only district courts and the Supreme Court. The Court of Appeals was not created by the legislature until 1983.

Of the composition of the Supreme Court, the Constitution specifies that there shall be a chief judge and no fewer than six, and no more than eight, associate Supreme Court judges. Today, the Minnesota Supreme Court has a chief judge and six associate judges.

The Minnesota Supreme Court serves as a court of appeals and well a court of original jurisdiction in certain cases. As an appellate court, it hears appeals from:

- Minnesota Court of Appeals decisions;

- District court decisions when the Supreme Court chooses to bypass the Court of Appeals;

- Tax court decisions; and

- Workers' Compensation Court of Appeals decisions.

The Minnesota Supreme Court takes original action regarding (Minnesota Judicial Branch, 2012b):

- automatic review of all first degree murder convictions (which require life without parole);

- writs of prohibition (which seek to prevent the government from taking some action);

- writs of habeas corpus (which require the government to justify why someone is in custody);

- writs of mandamus (which seek to compel the government to perform some act);

- disputes involving legislative elections; and

- attorney and judge disciplinary cases brought by the Lawyers Professional Responsibility Board and the Board on Judicial Standards, respectively.

Figure 3.1. How a Case Gets to the Supreme Court and What Happens to It

Each year, the Minnesota Supreme Court receives about 900 petitions for review. Prior to the creation of the Court of Appeals in 1983, the number was over 1,800 petitions annually. Petitioners must file a “petition for review” for

their cases to be considered by the Supreme Court. This is akin to petitioning to the U.S. Supreme Court for a writ of certiorari. Only about 5% of the cases petitioned to the Minnesota Supreme Court come from the Court of Appeals. Most of the cases come to the Supreme Court from the Tax Court, the Workers' Compensation Court of Appeals, and from petitioners requesting that the Supreme Court act under its original jurisdiction authority. Of the 900 cases on average for which the Supreme Court is petitioned, it actually accepts about 1 in 8 for review (Minnesota Judicial Branch, 2015d). The Supreme Court tends to focus on the most contentious constitutional and public policy issues.

The Supreme Court also possesses regulatory and administrative functions. The Supreme Court is the body responsible for regulating the practice of law in Minnesota, as well as enforcing standards of conduct for attorneys and judges in the state. The Court develops and implements rules and procedures for the practice of law in Minnesota. The Supreme Court is also tasked, through its administrative personnel, with overseeing the operations of the Minnesota court system state-wide.

The Minnesota Judicial Branch employs approximately 2,500 people, only a fraction of whom are judges. The annual budget for the entire Minnesota judicial branch totaled in excess of $290 million in Fiscal Year 2014. This includes $32,282,000 appropriated for the Supreme Court and the State Court Administration Office. In FY 2014, the salary for the Chief Judge of the Supreme Court was set at $167,002. Salary for each associate judge was set at $151,820.

Court of Appeals

The Minnesota Court of Appeals first began to operate on November 1, 1983. The Court of Appeals was created to relieve the case load of the Supreme Court by providing a prompt review of all final legal decisions of the district courts, as well as administrative and regulatory decisions of state and local government agencies. The Court of Appeals exists to correct legal errors committed at the district court level and handles 95% of all appeals in the state. The Court of Appeals hears or considers in conference approximately 2,400 cases each year.

The Court of Appeals in Minnesota has the quickest turn-around time on accepted cases in the United States. By law, the Court of Appeals must issue a decision within 90 days of oral arguments or 90 days of a case's scheduled conference date. No other appeals court in the country operates under a shorter imposed deadline for decisions. District judges in Minnesota operate under similar deadlines. Minnesota's computerized case management system alerts court

system officials, as well as oversight bodies such as the Board on Judicial Standards, when judges fail to render decisions in a timely manner.

The Minnesota Court of Appeals consists of 19 judges. The judges rotate into three-judge panels and travel throughout the state to hear oral arguments. The traveling nature of the Court of Appeals is intended to make access to appellate review less expensive and more broadly available to the citizens of Minnesota (Minnesota Judicial Branch, 2015a). The entire appellate court is housed, however, in St. Paul at the Minnesota Judicial Center.

The appropriated budget in Fiscal Year 2014 for the Court of Appeals in Minnesota was $10,641,000. The Chief Judge of the Court of Appeals had an annual salary of $150,206. The remaining 18 appellate judges earned $143,054 per year.

District Courts

In Minnesota, there are 10 judicial districts encompassing the state's 87 counties. Presiding over trials in these districts are 289 judges. There is at least one judge in each county. Every district is made up of two or more counties, with the exception of the two most populated counties in Minnesota—Hennepin and Ramsey Counties (which include the cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul, respectively). The Fourth Judicial District consists of Hennepin County and the Second Judicial District consists of Ramsey County.

District courts, or trial courts, are primarily courts of original jurisdiction. That is to say, cases are first heard, or originally heard, in district court. The kinds of cases heard in Minnesota district courts include: civil cases, criminal cases, family disputes, juvenile delinquency cases, probate cases, and violations of municipal and county ordinances. District courts serve as an appellate court for cases originating in housing court, probate/mental health court, and conciliation court, although such cases technically amount to a new trial rather than strictly an appeal on issues of law.

The administration of judicial districts is state administrative function. Each district is managed by the district's chief judge and assistant chief judge. Each district is also assigned a judicial district administrator. Additionally, the courthouse in each county is managed by a court administrator. Judicial district administrators and court administrators are Minnesota state employees of the State Court Administrator's Office. They are responsible for the day-to-day operation of the courts, including scheduling, filing legal documents, processing charges, human resources, budgeting, and other administrative functions.

By state law, all district courts are funded by the state rather than at the local level. This is to ensure equitable and quality jurisprudence state-wide. In

Fiscal Year 2014, the budget for the district courts collectively in Minnesota was $247,459,000. This includes an annual set salary of $141,003 for each of the 10 district chief judges, as well as an annual salary of $134,289 for the remaining 279 district judges.

Figure 3.2. Minnesota Judicial Districts

Figure 3.3. Minnesota Courts Structure

Problem-Solving Courts

Minnesota, like many other states, have created specialized problem-solving courts to deal with certain offenses therapeutically rather than punitively. Problem-solving courts target specific constituencies and attempt to get at the root causes of criminal behavior associated with issues to which the specialized

courts are tasked with addressing (Merchandani, 2008). The proliferation of problem-solving courts in the United States mirrors a broader court reform movement that has taken hold in England, Australia, and Canada (Berman & Feinblatt, 2005).

Minnesota's problem-solving courts include drug courts, DWI courts, domestic violence courts, veterans courts, community courts, and mental health courts. These courts are organized under the auspices of district courts. Chief among the specialized problem-solving courts in Minnesota are the drug courts. The first drug court in Minnesota was established in 1996 in Hennepin County (Minneapolis). By 2007, the number of drug courts had expanded to 27 (Minnesota Judicial Branch, 2012a). In 2015, Minnesota had 50 drug courts in operation.

Drug courts in Minnesota are designed to provide a coordinated response to criminal offenders who are dependent on drugs and alcohol. The coordination involves judges, prosecutors, defense attorneys, probation officers, the police, treatment providers, and drug court case managers. Offenders must undergo what is known as a Rule 25 assessment to determine eligibility for participation in a drug court program when public funding is to be used for chemical dependency treatment. A Rule 25 assessment results in a determination of treatment needs and strategies. At an individual level, the goal of these courts is to reduce recidivism among drug and alcohol offenders through sustained treatment and supervision. More broadly, the expressed goals of drug courts in Minnesota is to (Minnesota Judicial Branch, 2014b):

- Enhance public safety;

- Ensure participant accountability; and

- Reduce costs to society.

Over the years, Minnesota has had ample time to refine the structure and practices associated with its drug courts. The Minnesota Judicial Council, which is made up of leaders in the judiciary and constitutes the policy-making authority with the Minnesota judicial branch of government, has adopted 12 key standards by which all drug courts in Minnesota must operate. The standards have been derived from years of observation and evaluation of drug courts in the state and around the country, as well as from guidelines published by the U.S. Department of Justice. The standards for the operation of drug courts in Minnesota follows (Minnesota Judicial Branch, 2014b):

- Drug courts must utilize a comprehensive and inclusive collaborative planning process;

- Drug courts must incorporate a non-adversarial approach;

- Drug courts must have published eligibility and termination criteria that have been collaboratively developed, reviewed, and agreed upon by members of the drug court team;

- A coordinated strategy shall govern responses of the drug court team to each participant's performance and progress;

- Drug courts must promptly assess individuals and refer them to the appropriate services;

- A drug court must incorporate ongoing judicial interaction with each participant as an essential component of the court;

- Abstinence must be monitored by random, frequent, and observed alcohol and other drug testing protocols;

- Drug courts must provide prompt access to a continuum of approved alcohol, drug other related treatment and rehabilitation services, particularly ongoing mental health assessments, based on a standardized assessment of the individual's treatment needs;

- The drug court must have a plan to provide services that are individualized to meet the needs of each participant and incorporate evidence-based strategies for the participant population. Such plans must take into consideration services that are gender-responsive and culturally appropriate and that effectively address co-occurring disorders while promoting public safety;

- Immediate, graduated, and individualized sanctions and incentives must govern the responses of the drug court to each participant's compliance or noncompliance;

- Drug courts must assure continuing interdisciplinary education of its team members to promote effective drug court planning, implementation, and ongoing operations; and

- Drug courts must evaluate effectiveness.

The last standard emphasizes the need for program evaluation. When public monies and human resources are involved, it is not enough to engage in programs that are well-intentioned or merely seem like good ideas. Public programs and practices must be evidence-based. On this score, Minnesota drug courts appear to do quite well. In 2012, a study was conducted comparing over 500 drug court participants to approximately 650 offenders with similar profiles, but who did not enter a drug program. According to the study's findings, drug court participants (Minnesota Judicial Branch, 2014a):

- had lower rates of recidivism in the two years that followed;

- spent fewer days behind bars (which saved the state on average $3,200 per participant);

- showed gains in employment, educational achievement, home rental or ownership; and

- increased payment of child support over the run of the program.

Of course, a single study is not definitive. With program evaluations, there are always concerns about the adequacy of measures. This is for no fault of researchers; it is difficult to secure truly experimental conditions, samples, and measurements when dealing with real people in real programs.

For example, in the study above, it may be that the people selected for drug court as opposed to criminal court were so selected precisely because of their likelihood to succeed. It would be no surprise, then for these offenders to perform better than others who were not selected for drug court. While the offender profiles between participants and non-participants were similar, the only way to establish true cause and effect regarding drug courts is through experimental controls. But that would mean randomly selecting some people who might benefit from the drug court program to not go into the program, and randomly selecting others who likely would not benefit, to be placed into the drug court program. However, some would argue that doing so would be unethical. So, researchers are potentially left with only post-intervention observations of non-randomly identified participants and non-participants. Some social scientists researching Minnesota courts have largely overcome this methodological problem by comparing specialty court participants with matched samples from time periods before the specialty courts existed. The evidence we do have, in the form of aforementioned study and others conducted in Minnesota and around the country, is that there appears to be beneficial outcomes associated with participation in drug court for drug offenders.

A variant of Minnesota's drug courts are DWI courts. These courts, as with traditional drug courts, recognize the illness of addiction and the role it plays in recidivism if left untreated. Also, like traditional drug courts, DWI courts require a collaborative effort on the part of judges, prosecutors, defense attorneys, law enforcement, social services, and treatment providers. However, repeat DWI offenders pose a unique and substantial public safety concern that other addictions often do not entail. Consequently, DWI courts must also address transportation issues for offenders (which often challenge the ability of offenders to remain compliant) and rely on a regime of frequent alcohol-testing (NPC Research, 2014). To this end, the Minnesota Ignition Interlock Device Program was established in 2011 and is managed by the Minnesota Department of Public Safety. The optional program allows aggravated DWI offenders who are facing revocation or cancellation of their driver's licenses to retain their driving privileges provided they submit to the program protocols. The chief

element of the program is that offending drivers must have a device installed on their motor vehicles which require a successful breath test through a blow tube for the vehicle to start (Minnesota DVS, 2015).

While drug courts and DWI courts are the most prolific among Minnesota's specialized problem-solving courts, there are other such courts which have been established in various judicial districts around the state. Domestic violence courts in Minnesota are intended to counter typical problems associated with intimate partner and family violence. Such problems include low reporting, withdrawn charges, threats of retaliation made against victims, and high recidivism. Domestic violence courts overcome these problems by directing a high level of judicial scrutiny toward the offender and by close cooperation between the judicial branch and social service agencies (Minnesota Judicial Branch, 2015b). Offenders are customarily subjected to intense monitoring and strict compliance requirements, e.g. obeying protective orders, completing anger management and substance abuse counseling, etc. Court-appointed case managers are assigned to monitor the offender's compliance, but also work with the offender's attorney to ensure due process rights are preserved (Minnesota Judicial Branch, 2015b).

Minnesota has also embraced the strategy of specialized courts to confront domestic violence. In particular, the domestic violence courts throughout Minnesota exist to apply intense judicial supervision of repeat and dangerous domestic violence offenders in an effort to overcome traditional problems in these cases, namely (Minnesota Judicial Branch 2015e):

- infrequent reports

- withdrawn charges

- threats to victim

- lack of defendant accountability

- high recidivism

Steans County, seated in St. Cloud, provides a good example of how Minnesota's domestic violence courts are organized. Eleven different agencies and organizations participate in the program; these include city and county law enforcement agencies, the 7th Judicial District Court, the county attorney's office, community corrections, the local public defender's office, and various social service governmental and non-profit organizations. The domestic violence court in Stearns County, as in other counties around the state, focus on felony level offenders. In Minnesota, domestic violence is generally a misdemeanor offense akin to simple assault. However, repeat offenders, or offenders engaging domestic violence involving serious injuries or weapons, will face felony-level charges. It is this type of offender, particularly recidivists, who are

heavily scrutinized through this program. The stated goals of Minnesota's domestic violence court programs are bifurcated between offenders and victims. For offenders, the goals are (Stearns County, n.d.):

- reduction in violations of court ordered conditions of release and probation;

- increased compliance with treatment;

- elimination of violent behavior; and

- increased accountability (through sanctions) for continuing violence.

For the victims of domestic violence, the goals of the program are (Stearns County, n.d.):

- increased provision of support services for victims and families;

- increased safety for victims and families; and

- provision of a viable pathway to end the cycle of violence

Certainly, these are laudable goals of the district courts in partnership with other agencies and organizations. The actual effectiveness of these programs in reducing chronic domestic abuse continues to be evaluated at academic and public policy levels. However, many studies which have been conducted around the country do suggest some promise in the intensive intervention directed toward offenders and victims which these programs provide.

Minnesota's mental health courts specialize in dealing with individuals who have one or more psychiatric disabilities and who have been charged criminally. The intention in using mental health courts in certain cases is to focus on the alleged offender's mental health condition rather than the criminal behavior, given that the mental health condition is thought to be the precipitating cause of the criminal behavior. As with the other problem-solving courts, mental health courts create a structure by which judges, law enforcement, social services, and the medical and psychological service communities can partner together to strategically address an offender's underlying condition (Minnesota Judicial Branch, 2015c). Veterans courts, which are a relatively new iteration of mental health courts, expand on the strategies of mental health courts by recognizing the unique circumstances of veterans dealing with mental illness and who are have had trouble reintegrating into society after returning home from war-related deployment.

Judicial Selection and Elections

Judges at every level in Minnesota stand for election every six years. The elections are non-partisan. While elections have allowed for a system in which

judges are accountable to the people in the communities they serve, the fact that there is no political party identification attached to the candidates has made it difficult for some candidates to distinguish themselves from others. Historically, voters don't follow the rulings to judges very carefully. Unless a judge makes a highly publicized and unpopular ruling, most incumbents benefit from an easy path to re-election.

In recent years, judicial candidates have attempted to explain in some detail their legal philosophies and distinguish those philosophies from their opponents. For example, some candidates might wish to explain how tough on criminals they would be. Other candidates might wish to express their belief in judicial restraint—emphasizing the view that judges should be very reluctant to overrule the will of the people who act through their legislators, and whose will is reflected in the passage of laws.

While these kinds of statements are helpful to voters in delineating one judicial candidate from another, the Minnesota Supreme Court had promulgated rules making it improper for candidates to explain their legal perspectives so vividly—particularly if the position taken relates to issues which could come before the judge at some point in the future. Of course, virtually any issue falls into that category. This point eventually made its way to the United States Supreme Court. In

Republican Party of Minnesota v. White

(2002), the U.S. Supreme Court said that candidates running for judicial office should not be barred from explaining their views about legal issues before the courts. In a 5–4 decision, Justice Antonin Scalia wrote for the majority:

There is an obvious tension between the article of Minnesota's popularly approved Constitution which provides that judges shall be elected, and the Minnesota Supreme Court's announce clause which places most subjects of interest to the voters off limits.

The U.S. Supreme Court decided that elections imply messaging. You can't impede one's ability to cast himself or herself in a particular light, and his or her opposition in a different light, and still expect an election to be meaningful.

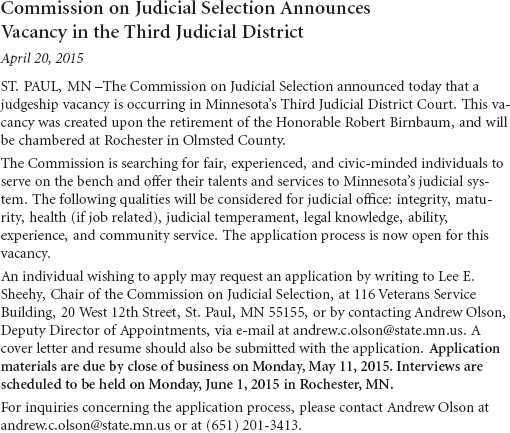

Minnesota Commission on Judicial Selection

When a judge retires from the bench, dies in office, or for some other reason must step down and a vacancy occurs during a judge's term, the governor of Minnesota will appoint a replacement to serve until the next election cycle. The Minnesota Commission on Judicial Selection exists to help the governor make a merit-based selection in such cases. When a vacancy occurs, the commission will seek and collect applications and nominations of attorneys and sitting

judges (for appellate court vacancies). The commission, which consists of 49 members—27 appointed by the governor and 22 appointed by the Supreme Court—will examine applications and nominations for qualities, such as knowledge of the law, judicial temperament, integrity, and a record of community service. An example of a solicitation of candidates for a judicial vacancy is provided below.

Figure 3.4. Solicitation of Candidates for a Judicial Vacancy

Once the commission identifies top candidates, based on judicial and employment records of the candidates and the recommendation letters received, the leading names will be submitted to the governor for his or her consideration and an appointment will be made.

Board on Judicial Standards

In 1972, Minnesota legislation was enacted to create the Board on Judicial Standards. This is a state board whose purpose is to enforce standards of conduct

among the Minnesota judiciary. The board consists of 10 gubernatorial appointees: four judges, two lawyers, and four public members (who are not lawyers or judges). The Board also employs an executive secretary to handle the day-to-day operations of the board.

The Board receives and investigates complaints of judicial misconduct. The Board does not assess or address alleged legal errors committed by judges. That is the role of appellate courts. Rather, the Board investigates allegations such as improper courtroom demeanor, improper or unprofessional treatment of parties; witnesses, court staff, jurors, attorneys, etc.; failing to dispose of judicial business in a timely manner; conflicts of interest; substance abuse; engaging in improper political and campaign activities; and other issues.

When the Board receives an allegation of judicial misconduct, it evaluates the complaint for merit. If the complaint appears to be worthy of further exploration, the Board will investigate the complaint (including interviewing relevant parties) and conduct hearings. If the allegation against a judge is sustained, the Board has a range of sanctions available to it that can be meted out to the offending judge. The possible sanctions include: issuing private letters of caution or reprimand, requiring training or other remedial action, or recommending suspensions or removals to the Supreme Court.

In 2013, the Board on Judicial Standards received a total of 108 written allegations of misconduct. Most complaints each year are dismissed by the Board without investigation because they are deemed to be frivolous or they do not allege an actual violation of the Code of Judicial Conduct. Many of these instead alleged an error of law, which is the purview of the appellate courts. In most cases, complaints are found to be without merit or outside the jurisdiction of the Board and therefore are dismissed. In 2013, a total of 16 complaints were fully investigated, and seven resulted in a public reprimand, private admonition, or a letter of caution (Minnesota Board on Judicial Standards, 2013).

Attorneys at Work in Minnesota's Judicial System

Minnesota Lawyers Professional Responsibility Board

A sister oversight organization of the Board on Judicial Standards is the Lawyers Professional Responsibility Board. While the Board on Judicial Standards polices the conduct of judges, the Lawyers Professional Responsibility Board polices the conduct of attorneys licensed to practice law in the State of

Minnesota. This board consists of lawyers and non-lawyer public members appointed by the Minnesota Supreme Court. The Board, in conjunction with the Office of Lawyers Professional Responsibility, receives and investigates complaints of unethical conduct alleged against practicing attorneys in Minnesota. The Lawyers Professional Responsibility Board may take action against an attorney's license to practice law in the state. Of course, if an attorney is suspended or disbarred in Minnesota for unethical conduct, he or she may still practice law in other states where the attorney is bar certified. It is not uncommon, however, for the Board to pass on information about the disposition of complaints and sanctions to other jurisdictions in which an attorney practices law.

In 2013, the Lawyers Professional Responsibility Board received 1,253 complaints. Of those, 43% were dismissed without an investigation and another 29% were dismissed after an investigation. Only 9% received some form of public discipline. The remaining cases resulted in private admonitions or became moot through attrition, i.e., death of the attorney being investigated, resignation, etc. (Lawyers Professional Responsibility Board, 2014).

Minnesota's Law Schools

Minnesota has three law schools within its borders. Most of the state's 24,000 practicing attorneys attended one of these schools. The only public Minnesota law school is operated by the University of Minnesota. The two private law schools are the Mitchell Hamline School of Law and the University of St. Thomas School of Law. All three of Minnesota's law schools are located in Minneapolis or St. Paul.

The University of Minnesota is the state's flagship university and the lone land grant university. The University of Minnesota was founded in 1851, seven years before the Territory of Minnesota became a state. The law school was founded in 1888, enrolling at the time 32 students in the day school and 35 in night school. Today, the University of Minnesota School of Law enrolls 855 students, including 732 in its traditional Juris Doctor (J.D.) program. The balance of students are enrolled in international and Master of Laws (LL.M.) programs. The school is Minnesota's top-ranked law school (ranked #20 nationwide by U.S. News and World Report). It is also the most expensive, despite being a public institution, with tuition topping $40,000 per year for state residents. About one-third of its students are Minnesota residents. Nearly 60% are men. Racial and ethnic minorities make up 19% of the student body.

The University of Minnesota School of Law boasts over 12,000 living alumni. These former students no doubt are primarily responsible for the law school

$95 million endowment. Despite the surplus of law graduates nationwide, the majority of graduates from the University of Minnesota School of Law find related employment. According to the National Association for Law Placement, less than 40% of law school graduates are employed as attorneys in permanent positions within 9 months of graduating. By contrast, over 98% of the 2012 University of Minnesota law school graduates were known to be permanently employed in 2013. The median starting salary for graduating attorneys from the University of Minnesota who sought positions in the private sector (which comprised 61% of graduates) was $102,000 in 2012 (University of Minnesota, 2015).

The second largest law school in Minnesota is the Mitchell Hamline School of Law. This law school was established in 2015 by the merger of the William Mitchell College of Law and the Hamline University School of Law. A little background on both schools is provided below.

The William Mitchell College of Law was founded in 1900 as the St. Paul College of Law. It was founded exclusively as a night law school for working students. The William Mitchell College of Law has many notable alums, including Supreme Court Chief Justice Warren Burger, several state Supreme Court justices (in Minnesota and other states), many federal district and appellate judges, governors, and members of Congress. William Mitchell has over 11,000 living alumni and was often viewed as Minnesota's other great law school. However, its overall ranking by U.S. News and World Report placed the College of Law at #135 leading up to the merger, which was the lowest ranking among Minnesota schools. As at its founding, William Mitchell provided legal education for students who were only able to attend at night and part-time. Its part-time option was always viewed as one of its great strengths. Indeed, U.S. News and World Report ranked the college #1 in the region for part-time legal education. The William Mitchell College of Law always emphasized the practice of law and applied lawyering skills (William Mitchell College of Law, 2015).

While there have been many William Mitchell Law graduates who have gone on to the federal bench and federal elected positions, much of the backbone of Minnesota's legal and political systems at the state level is made up of William Mitchell graduates as well. Currently, the college's graduates include 111 of the state's current district judges, six state senators, six state house members, nine state appellate court judges, 32 elected county attorneys, and Minnesota's elected Attorney General (William Mitchell College of Law, 2015).

Hamline University, located in St. Paul, Minnesota, is the oldest university in Minnesota, having started in 1854—four years prior to Minnesota joining the Union as a state. The Hamline University School of Law was founded in 1972 as an independent law school in Minnesota. In 1976, the school was acquired by Hamline University.

U.S. News and World Report

ranked Hamline

University's law school as the top private law school in Minnesota in 2015. The Hamline Law School placed considerable emphasis on experiential learning for its students, requiring 15 experiential credits to be completed by third year students. The school operated eight different law clinics which serve as conduits for gaining practitioner experience for students (Hamline School of Law, 2015).

In 2014, Hamline Law School enrolled 90 first-year law students, including 24 part-time students. A little under half of the matriculating students were women. Students came from 17 states and 10 different countries (Hamline School of Law, 2015). According to the Minnesota State Board of Law Examiners, Hamline Law graduates consistently performed well on the Minnesota Bar Exam. The pass rates for Hamline graduates from 2007 to 2012 ranged from a low of 88% to a high of 93%. Despite the favorable measures for these students, only about half of Hamline graduates found full-time employment practicing law within 9 months of graduation. The abundance of Hamline law graduates relative to the number of legal positions is consistent with law graduate employment trends generally. In fact, leading up to the merger, Hamline's placement trailed slightly the national average. According to the National Association for Law Placement (NALP), there were 46,776 new law school graduates nationwide in 2013. Roughly 58% of law school graduates were known to be employed in non-temporary attorney jobs nine months after graduation (NALP, 2014).

The third law school in Minnesota is the University of St. Thomas School of Law. Although the University of St. Thomas is located in St. Paul, the law school is located in downtown Minneapolis. The University of St. Thomas is Minnesota's largest private university and one of the largest and oldest Catholic universities in the country, having been founded in 1885. The present law school was constituted in 1999 and offered its first classes in 2001 and received its full accreditation from the American Bar Association in 2006. Interestingly, this is the second go-around for the St. Thomas School of Law. The university operated its law school from 1923 to 1933. That law school was shuttered in the wake of the Great Depression (St. Thomas School of Law, 2015a).

As with every law school in Minnesota, St. Thomas has a number of accolades it can point to which signifies its quality relative to other law schools around the country. For example, the publication

National Jurist

ranked St. Thomas School of Law the number one school in the country for practical training. This is significant as competitor Mitchell Hamline also touts its experiential bona fides. Additionally, the faculty at St. Thomas School of Law ranked 30th among the faculty of over 200 law schools nationwide for scholarly impact. In fact, the Princeton Review ranked the St. Thomas law faculty 8th on its 2014 “Best Professors” list (St. Thomas School of Law, 2015b).

The state of Minnesota, with recently four and now three law schools, has a population of 5.4 million people. In today's climate, with so many more law graduates than law positions available to them, many have come to believe that Minnesota has too many law schools given the state's size. Adam Wahlberg (2015) noted that the states of Maryland, Wisconsin, and Colorado—each with a similarly sized population as Minnesota—have only two law schools a piece.

The over-abundance of legal education options in the relatively small state of Minnesota, all of which are located in the same metropolitan area, and the competition for prospective law students from the region who did not get into the University of Minnesota, helps explain why the William Mitchell College of Law and the Hamline University Law School announced in February of 2015 that they would be merging into a single institution. The fact is, both schools saw a decline since 2011 of first-year enrollment near or above 50% (Weissmann, 2015). The merger, which might better be coined an “absorption” (Hamline into William Mitchell), was effective fall of 2015, after the American Bar Association approved the merger plan. There is also pending legal action because of the merger process. Two tenured law professors at William Mitchell College of Law filed a lawsuit over faculty layoffs stemming from the merger, which plaintiffs claimed amounted to a breach of contract.

Minnesota's Prosecutors

There are 87 county attorneys in Minnesota. The county attorney is an elected official who serves as the chief criminal prosecutor for a given county. He or she also provides legal counsel to the county board, pursues civil enforcement action for non-criminal cases, and represents the county in legal action concerning areas such as asset forfeiture, land use, zoning, and other public policy matters. Assistant county attorneys are staff attorneys of the County Attorney offices. They are non-elected civil servants who carry out the legal duties of the county attorney's office at the behest of the elected county attorney, just as deputy sheriffs carry out the duties of an elected county sheriff.

County attorneys and their assistants are responsible for determining appropriate charges in criminal cases, filing those charges by way of a criminal complaint or by securing a grand jury indictment, and prosecuting the cases once charges are formalized. The county prosecutor's first court appearance in a criminal case is the initial appearance. For petty misdemeanor and misdemeanor offenses, the initial appearance for the defendant is the arraignment. It is during this hearing that the defendant will be asked to enter a plea of guilty or not guilty to the charge(s). In more serious cases (gross misdemeanors and

felonies), the initial appearance before the judge, known as a Rule 5 hearing, does not result in a plea. Rather, the judge will explain to the defendant what his or her rights are and is notified of the formal charges (Washington County, 2015).

As is the case with prosecuting offices all around the country, there is a strong preference among Minnesota county prosecutors for resolving cases through plea bargaining before they ever make it to trial. Prosecutors along with defense attorneys and judges make up the courtroom workgroup. Although the criminal justice system in the United States is ostensibly adversarial, in reality these individuals often work together to resolve criminal cases to a degree that is mutually satisfying. Neubauer and Meinhold (2013) note that there are different types of plea bargains. Charge bargaining is when the defendant is afforded an opportunity to plead guilty to less serious charges than the one originally specified. Count bargaining is when a defendant pleads guilty to fewer criminal charges than originally specified. Finally, sentence bargaining involves the defendant pleading guilty on the basis of the promise of a specific sentence. Ultimately, however, a promised sentence is really only a promised recommended sentence to the judge. A judge may always choose to disregard a plea agreement—particularly when the assigned punishment is a part of the deal. Prosecutors in Minnesota and around the country regularly use all three types of plea bargaining to facilitate the resolution of criminal cases in one's county.

Criminologist Samuel Walker identified a number of prosecutorial decision points which serve to highlight the amount of discretion prosecutors have in deciding who gets charged with what, regardless of what the police may recommend. These decision points include (Walker, 1993):

- decision to charge or dismiss

- decision on the top charge

- decision on the number of charges

- decision on using or deferring to a grand jury (see Appendix 3.1

)

- decision to plea bargain

While factors such as available time and resources and the law enforcement priorities of the day will influence prosecutors at the decision point junctures, a key factor is simply the strength of one's case. Joan Jacoby (1979) identified the importance of case qualities in discretionary making prosecutorial decisions. She offered three models to explain the variance in the attractiveness of criminal cases. The Legal Sufficiency Model requires only minimum level of legal elements necessary to prove a case. Many of these cases will eventually be dismissed because of substandard evidence, witness problems, and other issues. The System Efficiency Model involves screening out weak cases. However, the

majority of the cases which are left are disposed of outside of court. Emphasis on the use of plea bargains to make the system (or some would say, the assembly line) continue to operate smoothly. The final model identified by Jacoby—the Trial Sufficiency Model—involves the most stringent approach to case screening. Prosecutors operating under this model (often federal prosecutors) will only accept cases that would clearly win at trial. While plea bargains may still be considered, prosecutors who have determined a case to be trial sufficient have less incentive to consider significant reductions in the number or type of charges or probably prison time.

In addition to county attorneys, the State of Minnesota Office of the Attorney General participates in the criminal justice process. The Attorney General's office represents the State of Minnesota in state and federal court much like the county attorney's office represents county governments in court. The Attorney General is the chief source of legal advice for state agencies and provides education and legal opinions to local prosecutors on various criminal matters which have a statewide impact. The Office of Attorney General takes the lead on most criminal appeals in the state. The office also plays a significant role in combating consumer fraud by going after fraudulent businesses civilly and criminally.

Finally, city attorneys also play a significant prosecutorial role in Minnesota. In larger cities, such as Minneapolis and St. Paul, city attorneys are staff municipal employees; in smaller towns, city attorneys are often private practice lawyers in the community with whom the municipality contracts to act as the city attorney. City attorneys in Minnesota are responsible for prosecuting most petty misdemeanor and misdemeanor state-level offenses (especially traffic violations and DWIs) and city ordinance violations (such as nuisance offenses).

Minnesota's Public Defenders

Just as there is a network of prosecutors around the state to levy criminal charges as appropriate, so too are there public defenders in all 10 judicial districts poised to provide legal counsel to accused offenders who are unable to afford procuring legal assistance themselves. The work of public defenders across the state is coordinated by the Minnesota Board of Public Defense. The Board oversees a statewide staff of attorneys who work fulltime as publicly funded defense attorneys. The state's public defender needs are supplemented by private, non-profit public defense corporations. These organizations are funded through grants and donations and provide indigent defendants, often persons of color, with legal and paralegal assistance.

Victims' Rights in Minnesota

In many states, services provided to crime victims to help them navigate the criminal justice system and to recover from their victimization are provided through court services offices. In the state of Minnesota, victims' rights, counseling, and advocacy services come from a myriad of sources, including the courts, police department, prosecutors' offices, and social service agencies. State statute defines crime victims as “... persons who incur loss or harm as a result of a crime, including a good faith effort to prevent a crime” (Minnesota Statutes §611A.01b). Crime victims in Minnesota have many rights under state law. Minnesota Statutes §611A.02 requires law enforcement officers to notify alleged victims of their many rights under the law, including and particularly the availability of victim support services and counseling and concerning the right of victims to seek victim compensation from the state.

Victims are often thought to be victimized twice when they fall prey to criminal activity. They are first victimized by the crime itself. This harm manifests itself in physical injury, lost wages due to injury, property loss through damage or theft, and financial loss. But then many victims are victimized a second time through their participation in the criminal justice process. This is known as double victimization. Costs to a victim because of their cooperation with criminal justice authorities in an effort to secure justice include (Doerner & Lab, 2014):

- Time loss (due to court delays and cancelled proceedings)

- Lost wages (do to court appearances)

- Transportation and parking costs

- Intimidation by offenders, their families, and their friends

Through victim services an effort is made to mitigate the prospect of being victimized twice by a criminal episode.

Of course, one of the chief concerns for any victim is financial loss. Being victimized by crime—especially violent crime resulting in the death or side-lining of a family income earner—can devastate a family. The emotional toll is easy to imagine. But that toll is compounded when the bills, expected and unexpected, begin to mount. There are different remedies a crime victim might pursue to be made whole again financially. In some cases, insurance payouts provide relief (for those who have it). A civil suit against the offender is another option; but in many cases, criminal offenders and their families do not have deep pockets. Lawsuits are expensive and a civil judgment on paper against an indigent defendant goes very little distance toward paying the bills. Further, this all assumes the offender is known and identifiable. A third mechanism for a victim to be made whole financially is restitution. Restitution is court ordered as

part of a convicted offender's punishment. However, restitution is no more a panacea than are civil judgments as it requires a perpetrator to be identified and further, for him or her to have financial means (Doerner & Lab, 2011).

The fourth mechanism to help make victims whole by restoring them to pre-victim conditions is victim compensation. To this end, the Minnesota Crime Victims Reparations Board exists to provide victims with financial support. The board is not a part of the Minnesota Judicial Branch, but instead is located in the Department of Public Safety's Office of Justice Programs. Different public policy arguments exist for a government agency to provide direct monetary compensation for criminal victimization. On a broader level, there is the argument that the state has a social contract with its citizens and delivering assistance after the fact of crime is an extension of its obligation to protect citizens from the criminal elements. A more acute public policy rationale is that crime victims are just another class of citizens in need, and government in the United States has a long history of providing welfare benefits to people in times of need (Doerner & Lab, 2011).

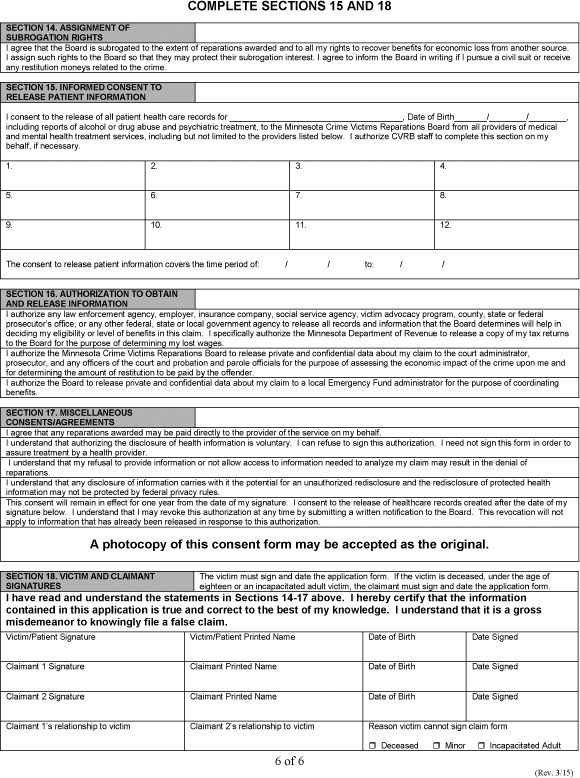

It is not clear which, if either, rationale Minnesota relied upon when the Minnesota Crime Victims Reparations Board was created in 1974, but its goal has always been to reduce the economic impact of violent crime on victims and their families (Office of Justice Programs, 2015). Today, if you are a victim of certain violent crimes in Minnesota, you are eligible to apply for financial assistance. Of course, completing the application form is no small task (see

Appendix 3.2

). Crimes which make for eligible victims are: homicide, assault, child abuse, sexual assault, robbery, kidnapping, domestic abuse, stalking, and criminal vehicular operation and drunk driving resulting in injury or death. Property crimes alone are not eligible triggers for reparations. In order to receive reparations, which in Minnesota can total as much as $50,000, one must have reported the crime to police within 30 days of the incident, the offender must not be unjustly enriched by the reparations (as is sometimes the case in domestic violence cases), and the victim must cooperate fully with law enforcement (Office of Justice Programs, 2015). This last requirement is key to securing the participation of victims in the criminal justice process despite the looming prospect of “double victimization.” Covered expenses include (Office of Justice Programs, 2015):

- medical and dental expenses

- counseling

- lost wages

- funeral/burial expenses

- survivor's benefits

- miscellaneous other expenses

Crime victims in Minnesota also have many rights unrelated to financial loss; instead, certain rights are focused on their dignity and emotional wellbeing. These rights include being notified about the release of offenders from incarceration, having victim identities concealed from the public for certain types of crimes, being kept apprised of the criminal justice processes at work involving their case, and having an opportunity to provide victim impact statements to the court at the time of sentencing.

Victim impact statements are especially beneficial to victims as they are given voice through spoken word, written statement, or both in court. These statements allow victims to explain to judges and juries about how the criminal episode has affected them and their families. It gives victims a chance to address offenders in a face-to-face forum if the victims so choose. Victim impact statements are not evidence. They are not delivered to the court members until sentencing, which of course occurs after conviction. Statements relating to how victims have been impacted by the crime are strictly limited in court because they are so prejudicial and yet, in most cases, provide little evidentiary value to the case.

Although Minnesota uses sentencing guidelines in determining criminal sanctions for offenders (see

Chapter Nine

), the testimony of victims during the sentencing phase can indeed have an impact on the punishment handed down. Even within the sentencing guidelines, judges have available to them a sentencing range which permits a sentence above the guidelines' presumptive sentence for a given crime committed by an offender with a given criminal history. What's more, the judge may elect an upward departure from the guidelines' range if there are aggravating circumstances, many times of which emerge from the victim impact statements.

Concluding Remarks

This chapter has explored the structure, processes, and mechanisms of accountability of the judiciary in Minnesota. As is the case at the national level of government, the judiciary in Minnesota is constitutionally prescribed and exists in three layers: the district courts, the appellate court, and the Supreme Court. Additionally, the state's myriad of problem-solving courts which operate under the authority of the district courts was considered. The chapter also examined the legal community—particularly within the criminal justice context—which consumes the services of the judicial branch. This includes prosecutors at the state, county, and municipal level, and defense attorneys. Finally, the rights of crime victims who must navigate judicial processes to secure justice for themselves and family members were highlighted. It should be

evident to readers of this chapter that Minnesota's judicial branch is a robust and essential element of Minnesota's government and criminal justice efforts.

Key Terms

Attorney General

Board on Judicial Standards

Charge Bargaining

Count Bargaining

County Attorney

Court of Appeals

District Court

Domestic Violence Court

Drug Court

DWI Court

Grand Jury

Minnesota Board of Public Defense

Minnesota Lawyers Professional Responsibility Board

Problem-Solving Courts

Republican Party of Minnesota v. White

Rule 25 Assessment

Sentence Bargaining

Supreme Court

Victim Compensation

Victim Impact Statements

Writ of Prohibition

Writ of Habeas Corpus

Writ of Mandamus

Selected Internet Sites

Discussion Questions

- What qualities are desired for someone to become a judge?

- Do we have too many lawyers in society? Why or why not?

- What considerations should guide a prosecutor in deciding how to charge a case?

- Are plea bargains fair to the accused offender? The victim? Society?

- Are problem-solving courts, which depart from traditional court processes, a good thing? Explain.

- Should the government pay crime victims money to help them out? What kind of crimes should qualify? What expenses should qualify?

References

Berman, G. & Feinblatt, J. (2005).

Good Courts: The case for problem-solving justice

. New York: New York Press.

Doerner, W. & Lab, S. (2014).

Victimology

. Boston, MA: Anderson/Elsevier.

Jacoby, J. (1979). The charging policies of prosecutors. In W. McDonald (ed.)

The Prosecutor

. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Merchandani, R. (2008). Beyond therapy: Problem-solving courts and the deliberative democratic state,

Law & Social Inquiry, 33

(4), 853–893.

Minnesota Judicial Branch. (2014b).

Minnesota offender drug court standards: Policy 511.1

. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Judicial Council.

Minnesota Judicial Branch. (2012b).

The Minnesota Supreme Court

. St. Paul, MN: Court Information Office.

Neubauer, D. & Meinhold, S. (2013).

Judicial process: Law, courts, and politics in the United States

. Boston, MA: Wadsworth.

Republican Party of Minnesota v. White

, 536 US 765 (2002).

Wahlberg, A. (2015, February 18). Why William Mitchell and Hamline law had to merge.

MinnPost.

Walker, S. (1993).

Taming the system: The control of discretion in criminal justice, 1950-1990

. New York: Oxford University Press.

Weissmann, J. (2015). The great law school bust is about to claim its first victim.

Slate

.

Appendix 3.1. The Important Role of Grand Juries

in the Minnesota Criminal Justice System

*

James C. Backstrom

1

Dakota County Attorney

Grand juries have been front and center in the national news recently. While each state in our nation has different forms of grand juries, this legal forum has been a fundamental part of the criminal justice system in America since our nation was founded. Grand juries have their origin in English law (as much of our legal system does) and were initially created as a check upon the unrestricted power of the sovereign or government to decide who should be charged with a criminal offense.

2

Today, grand juries continue to provide a check and balance upon the discretion afforded American prosecutors in the criminal charging process. They also provide a forum for prosecutors to seek direction from the citizens of their community in other cases where the charging decision is a particularly difficult one given the nature of the case or the prosecutor otherwise wishes citizen involvement in the charging process.

A grand jury is an independent decision making body comprised of individuals unrelated to the parties brought before it. In some jurisdictions grand juries must approve all serious criminal charges either before the commencement of a case or before the matter proceeds to trial.

3

In Minnesota, a grand jury is convened by the court upon the request of the prosecutor and these proceedings are mandated by law to occur before any criminal case goes to trial where the ultimate sanction, if the suspect is convicted, is life in prison.

4

This includes charges of first degree murder, treason and some violent rapes under Minnesota law.

5

In these cases, where a person's liberty could be taken away for life, Minnesota's law appropriately requires an extra check upon a prosecutor's authority to initiate criminal charges without independent review.

By custom and practice, grand juries also often hear cases involving a shooting death caused by a police officer. This is to avoid any appearance of conflict

of interest due to the close working relationship between prosecutors and law enforcement agencies. It is also done to assure public confidence in the decision being made.

Grand jury proceedings are not public trials, but rather are private investigative inquiries which must be conducted with absolute fairness. There are specific reasons for maintaining the secrecy of the grand jury process. Unlike a jury trial where the determination by jurors is whether someone has been proven guilty of a crime, grand juries (like prosecutors in the vast majority of cases) are reviewing evidence gathered by law enforcement agencies to determine if someone should be charged with a crime. This important decision making process should not be one conducted in a public setting as doing so may jeopardize the integrity of an on-going criminal investigation.

6

In addition, the Minnesota Supreme Court has made it clear on two separate occasions that a grand jury may not issue a written investigation report to the public which could damage the reputation of individuals not formally charged by indictment with a crime.

7

Secrecy of a grand jury proceeding also exists to encourage witnesses to come forward, to shield persons from public scrutiny of what the grand jury may determine are allegations which are either unfounded or insufficient to warrant prosecution, and to allow the citizen members of a grand jury to make these difficult decisions without threat of reprisal or public rebuke. Many cases presented to a grand jury are high profile in nature. It is not appropriate to place grand jurors in a situation where they could be publicly criticized if their decision is not a popular one in the eyes of some beholders. Prosecutors are elected officials who have willingly chosen to place themselves in the public eye for scrutiny of their decisions. Citizen members of a grand jury are not obligated to explain the basis for their decisions, nor should they be subject to public pressure to do so.

In some ways, a grand jury acts as a judge. The finding of probable cause is a judicial decision which in the vast majority of prosecutions is made by a judge, who determines whether the facts attested to under oath by a law enforcement officer in a document known in Minnesota as a criminal complaint constitutes probable cause for the charges being filed by the prosecutor. A grand jury makes the finding of probable cause in cases presented to it.

8

A grand jury, however, also acts as a prosecutor in making the determination of whether or not someone should be charged with a crime given the facts of the case. Prosecutors are known as “ministers of justice”

9

and have a higher ethical standard than simply finding probable cause exists to support a criminal charge.

10

In addition to finding probable cause, before filing criminal charges a prosecutor must make an independent judgment, based upon the available and admissible evidence, that there is a reasonable likelihood of proving a defendant guilty by proof beyond a reasonable doubt to the satisfaction of all twelve trial jurors when the case goes to trial.

11

Because grand jurors are in essence making a charging decision in lieu of the prosecutor, they too need to consider whether there is a reasonable likelihood of proving the defendant guilty at trial before finding that criminal charges are warranted.

In some states grand juries can conduct independent investigations without the presence or involvement of a prosecutor.

12

This does not occur in Minnesota, which is a good thing. The powers to investigate alleged criminal wrongdoing and to charge someone with a crime are two of the most significant actions a government can take against an individual and it is important to have a prosecutor, who is learned in the law, lead such inquiries.

Leading such inquiries, however, does not mean controlling them. Grand juries are not, as some claim, merely a rubber stamp for what a prosecutor wants to occur. A grand jury proceeding is not a forum for the prosecutor to argue why someone should be charged with or convicted of a crime. A grand jury operates independently of the prosecutor and grand jurors must base their decision upon all the evidence presented to them, along with the applicable law and the interests of justice. Prosecutors insure that only evidence that will be admissible at trial is heard and considered by a grand jury

13

and that the inquiry is conducted fairly and without bias in any form. Prosecutors are also

required to present to the grand jury evidence which may tend to exonerate a suspect.

14

A charging decision by necessity involves discretion and reasonable minds can differ when weighing the facts, law, and interests of justice in determining what criminal charges, if any, are appropriate. Consequently, a grand jury need not be unanimous in its decision. In Minnesota grand juries consist of 16 to 23 jurors, at least 12 of whom must agree to return an indictment (the name given the criminal charging document in the grand jury process) or a “no bill” (the name given the document signifying that no criminal charges are appropriate).

15

A weak grand jury which fails to charge those who should be charged with a crime, or a reckless grand jury which indicts those who should not be criminally charged, are equally problematic. The private and independent investigations and determinations of a grand jury are, and should remain, an important and integral part of criminal justice in our state and nation.

*

Reprinted with permission.

1.

James C. Backstrom has served as the elected prosecutor in Dakota County, Minnesota, since 1987 and is a member of the Board of Directors of the National District Attorneys Association and Minnesota County Attorneys Association.

2.

State v. Iosue

, 19 N.W.2d 735, 739-40 (Minn. 1945);

Costello v. U.S.

, 350 U.S. 359, 362 (1956).

3.

4 Crim. Proc. §15.1(d) (3d ed.).

4.

Minn. R. Crim. P. 17.01, subd. 1.

5.

Minn. Stat. §609.185 (Murder in the First Degree); Minn. Stat. §609.385 (Treason); and Minn. Stat. §609.3455 (Dangerous Sex Offender Sentences).

6.

State v. Falcone

, 195 N.W.2d 572, 575 (Minn. 1972);

U.S. v. Procter & Gamble Co.

, 356 U.S. 677, 681-82 (1958).

7.

In re Grand Jury of Hennepin County Impaneled on November 24, 1975

, 271 N.W.2d 817 (1978);

In re Grand Jury of Wabasha County

, 244 N.W.2d 253 (1976).

8.

State v. Eibensteiner

, 690 N.W.2d 140, 150 (Minn. Ct. App. 2004); Minn. R. Crim. P. 18.05, subd. 2.

9

.

See

Comment to Rule 3.8 of the American Bar Association's Model Rules of Professional Conduct and the Minnesota Rules of Professional Conduct.

10.

Bennett L. Gershman,

A Moral Standard for the Prosecutor's Exercise of the Charging Discretion

, 20 Fordham Urb. L.J. 513 (1992); Minn. R. Prof'l Conduct 3.8(a); Model R. Prof'l Conduct 3.8(a).

11.

Bennett L. Gershman,

A Moral Standard for the Prosecutor's Exercise of the Charging Discretion

, 20 Fordham Urb. L.J. 513 (1992); Minn. R. Prof'l Conduct 3.8(a); Model R. Prof'l Conduct 3.8(a).

12.

State v. Cosgrove

, 186 Conn. 476, 479–80, 442 A.2d 1320, 1322 (1982);

State v. Colson

, 262 N.C. 506, 512-13, 138 S.E.2d 121, 126 (1964);

Ex parte McLeod

, 272 S.C. 373, 377, 252 S.E.2d 126, 128 (1979).

13.

Minn. R. Crim. P. 18.05, subd. 1;

State v. Roan

, 532 N.W.2d 563, 570 (Minn. 1995).

14.

State v. Morrow

, 834 N.W.2d 715, 721 (Minn. 2013).

15.

Minn. R. Crim. P. 18.02, subd. 1; Minn. R. Crim. P. 18.06.

Appendix 3.2. Reparations Claim Form