Chapter Eight

The State and District of

Minnesota: The Federal

Criminal Justice System

at Work

Learning Objectives

- Describe those powers enumerated in the U.S. Constitution as belonging to the federal government and contrast those with the powers belonging to the states

- Explain key elements of the Judiciary Act of 1789

- Identify the early manifestations of federal law enforcement in the United States

- Contrast the responsibilities of federal law enforcement with those of state and local law enforcement

- Explain the presence of the federal courts in Minnesota

- Distinguish district court judges from magistrate judges

- Summarize the role of the United States Attorney in the federal criminal justice system

- Describe the jurisdiction of the Federal Bureau of Investigation and other key federal agencies

- Identify and describe federal correctional facilities in Minnesota

Most of this book is focused on elements of the criminal justice and legal systems in Minnesota which are delivered by the state and local governments. However, a significant portion of the business of criminal justice within the state, as in every state, is a product of the United States federal government. Indeed, within Minnesota, the United States government is visibly present through many federal law enforcement agencies, federal corrections facilities, and the federal courts.

History of Federal Criminal Justice in the United States

Before examining the details of the federal criminal justice apparatus in Minnesota today, it is helpful to understand the history and nature of the federal criminal justice system. Having an understanding of this system enables one to better contrast the role of federal criminal justice organizations in Minnesota with those belonging to Minnesota's state and local governments.

The United States Constitution, at least in its explicit language, envisions a limited criminal justice role for the national government. There is no general police power bestowed on the federal government. Instead, general powers including police powers are reserved to the states. James Madison, the chief author of the Constitution, wrote in

Federalist 45

that the powers of the national government, under the Constitution, were “few and defined” and related principally to external objects such as war, peace, foreign commerce, and taxation relating to foreign commerce. By contrast, the powers of the states, Madison wrote, were “numerous and indefinite” and related to the lives, liberties, and properties of the people, the internal order, improvement and prosperity of the state (Madison, 1788).

This principle was solidified in the 10th Amendment of the Constitution, which reads:

The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.

The states were considered sovereigns; sovereign governments can police their own people and territory as they see fit.

However if the states were given the general powers to police their citizens, what powers did the federal government have under the Constitution, particularly as related to criminal justice matters? The federal government was indeed assigned by the Constitution specific areas to regulate. Article I, Section 8, known as the Necessary and Proper Clause, states that Congress has the authority to “make all laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into the execution the foregoing powers, and all other powers vested by this Constitution in the government of the United States ...”

The foregoing powers mentioned in the Necessary and Proper clause relate to:

- taxation

- interstate and international commerce

- immigration and naturalization

- bankruptcy

- counterfeiting securities and coin

- piracy

- insurrection

These various domains for Congress, and by extension the federal government, to operate within are among Congress' enumerated powers. These are the regulatory areas specified in the Constitution as belonging to the federal government rather than to the states. Most federal criminal laws are connected in some way (sometimes very tenuously) to the enumerated powers above.

Perhaps the single most important piece of legislation with regard to America's federal criminal justice system was the Judiciary Act of 1789. While many elements of this law have been amended and modified over time, the basic framework for the criminal justice and legal systems at the national level, handed down via the Judiciary Act of 1789, remains in place today. Through this law, Congress exercised its Constitutional prerogative to create a federal court system. While the United States Constitution established a Supreme Court to serve as a co-equal branch of government with the Congress and the Presidency, the set-up of district and appellate courts was left to the Congress. Article III, Section 1 of the Constitution reads:

The judicial Power of the United States shall be vested in one supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish. The Judges, both of the supreme and inferior Courts, shall hold their Offices during good Behavior, and shall, at stated Times, receive for their Services a Compensation, which shall not be diminished during their Continuance in Office.

The Judiciary Act created the basic 3-tiered structure of the federal court system in place today, which include district courts, circuit courts of appeal, and the Supreme Court. The federal judiciary in the whole was to adjudicate all civil and criminal matters under the authority of the United States, bankruptcy matters, treaty disputes, and disputes between states.

United States Attorney

The Judiciary Act also created the office of United States Attorney for each federal judicial district. In 1789, each of the 13 original states constituted the boundaries of a federal judicial district. Many states today contain more than one judicial district; however (then and now), no state contains fewer than one complete judicial district. The responsibility of the United States Attorney in each district was to “prosecute and conduct all suits in such Courts in which the United States shall be concerned and to give his advice and opinion upon questions of law when required by the President of the United States and when requested by the Heads of any of the Departments, touching any matters that may concern their departments” (Bumgarner, 2006, p. 30).

United States Marshal

Still another important creation of the Judiciary Act of 1789 was the office of United States Marshal for each federal judicial district. United States Marshals and the deputy U.S. marshals they appointed to work for them arguably constitute America's first federal law enforcement officers as these officials were the first created by statute to possess exclusively law enforcement-related duties. The responsibilities of U.S. marshals early in America's history resembled those of local sheriffs—with the significant caveat that their authority was derived from the national government. The duties of U.S. marshals and deputy U.S. marshals in the late 18th century (and continuing to this day) included the serving of federal court orders, capturing and delivering to court federal fugitives, and compelling citizens to serve on federal juries within their districts (Calhoun, 1989).

The U.S. marshals in each district also served as the primary federal investigative agency throughout the 19th century. U.S. marshals were responsible for enforcing the Alien Act of 1798 (which required the deportation of foreigners deemed dangerous), the Sedition Act of 1798 (which criminalized criticism of the United State government), anti-slave trade laws and, ironically, at the same time, the Fugitive Slave Act. In other words, U.S. marshals were simultaneously responsible for enforcing federal laws to restrict and even suffocate

the slave trade while also protecting the property interest of slave owners in individual slaves who escaped their captivity and fled to northern states where slavery was illegal (Bumgarner, Crawford, & Burns, 2013). Over time, the investigative responsibilities of U.S. marshals with regard to federal crimes diminished as new federal law enforcement agencies were created, most notably the Justice Department's Bureau of Investigation in 1908 (later to become the Federal Bureau of Investigation).

Other Early Federal Law Enforcement Agencies

While the U.S. marshals certainly were among the earliest to carry out law enforcement responsibilities at the federal level, they were not entirely alone. Indeed, early post-colonial America saw federal law enforcement manifest itself in at least four ways, with law enforcement service to the federal judiciary being only one of them. The early manifestations were (Bumgarner, et al, 2013):

- Serving the Judiciary

- Enforcing tariffs and taxes on imports

- Protecting the postal system

- Protecting federal real property

The enforcement of taxes and tariffs was a major manifestation of federal law enforcement in America's early history. Several federal law enforcement agencies today trace their origin to this early governmental mission, including the U.S. Coast Guard, the Bureau of Immigration and Customs Enforcement, and the Internal Revenue Service. In 1789, Congress passed two very important pieces of legislation relating to the collection of tariffs. The Tariff Act of 1789 authorized the federal government to collect duties on imported goods. In tandem with this law, the Fifth Act of Congress was passed to create the first federal agency: U.S. Customs. The Customs Bureau was placed under the control of the U.S. Department of the Treasury. The Customs Bureau employed “collectors” in each of the 59 customs districts. U.S. Customs also employed “surveyors” and naval officers to assist the collectors in securing owed tariffs (Saba, 2003).

In 1790, Congress appropriated to U.S. Customs 10 naval warships to be used by surveyors and naval personnel to enforce tariff and trade laws. These ships became the fleet of the Revenue Cutter Service. The Revenue Cutter Service, which was part of the Treasury Department's Customs Bureau, also enforced smuggling, piracy, and anti-slave trade laws, including one law from 1794 which barred the use of American-flagged vessels in the slave trade and another in 1808 which prohibited the introduction of new slaves from Africa into the United States (U.S. Coast Guard, 2002).

Another manifestation of federal law enforcement early in America's history related to the United States Post Office (later to become the U.S. Postal Service). The United States Constitution gives the federal government exclusive authority to establish and maintain a postal system. America's post-colonial postal system was based on the colonial postal system set up by Benjamin Franklin, who became the colonial postmaster general in 1753. He held that position for many years. In 1772, he created the position of “surveyor.” Surveyors for the postal system were responsible for enforcing postal regulations and carrying out audit functions. In 1792, the Postal Service was established as a permanent federal agency. In 1801, the working title for surveyors was changed to “special agent,” which is perhaps the earliest example of the use of this term for federal criminal investigators (U.S. Postal Service, 2012).

By 1830, the Postal Service created within itself the Office of Instructions and Mail Depredations. The term “depredation” means “raid, an attack, or damage and/or loss.” The term was fitting for the title of the office, given its duties. Postal service special agents were organized into this bureau and formally served as the investigative and inspection branch of the United States Post Office. Special agents were responsible for investigating and preventing embezzlement, robberies of mail riders, stage coaches, steamboats, and later, trains. Postal special agents possessed statutory authority to carry firearms and make arrests (Bumgarner, 2006).

Still another early manifestation of federal law enforcement related to the securing and policing of federal property. In 1790, Congress began to meet temporarily in Philadelphia for a 10-year period while public buildings were constructed in the newly established District of Columbia, which was designated to be the nation's capital. It was thought that the capital of the United States should be located on federal territory not belonging to any particular state. A congressional commission was formed to manage federal real property in the District of Columbia during and after construction was completed (Senate Historian, nd). The Commission initially hired six night watchmen to protect federal buildings in Washington DC. In 1802, a superintendent of federal buildings was appointed who oversaw the activities of the watchmen. A few years later, in 1816, the Office of the Commissioner of Public Buildings was established as the management of federal property became too complex for a lone superintendent. Likewise, the policing of federal property became more complex as the number of public buildings grew and the federal footprint on the ground was enlarged (Bumgarner, 2006). In 1828, Congress formally authorized a Capitol Police Force. The responsibilities of this police force included patrolling the Capitol grounds and other public buildings. Much later, in 1849 when the Department of Interior was established, the organization of the Capitol Police were moved under the umbrella of the Interior Department. Today, several uniformed federal

police organizations look to the appointment of those six night watchmen in 1790 as a part of their heritage. These agencies include today's Capitol Police, the Supreme Court Police, the Federal Protective Service, the U.S. Park Police, and many other federal police and security agencies (Bumgarner, et al., 2013).

Interestingly, the four early manifestations of federal law enforcement (i.e, serving the judiciary, taxes and tariff enforcement, protecting the postal system, and securing federal property) still exist through various federal agencies today. What's more, agencies which are engaged in these functions, and in many others, are all present in Minnesota.

The Federal Courts

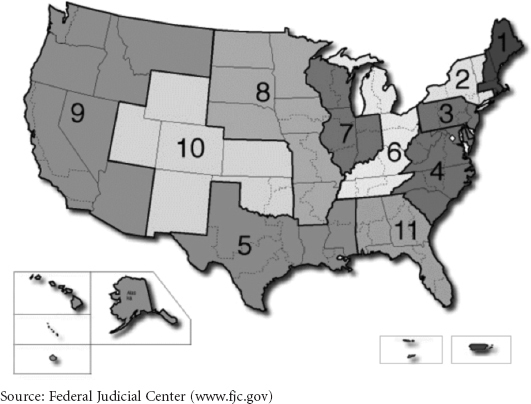

Minnesota is a state which possesses only one federal judicial district. The District of Minnesota is a part of the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals. The Eighth Circuit includes the districts of Minnesota, North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, Northern Iowa, Southern Iowa, Western Missouri, Eastern Missouri, Western Arkansas, and Eastern Arkansas.

Figure 8.1. Federal District and Appellate Court Map

Although a single judicial district, federal justice is dispensed through four federal courthouses in Minnesota. The two main federal court buildings are located in St. Paul and Minneapolis. However, there are also federal courthouses in Duluth and Fergus Falls. The St. Paul federal courthouse is home to five federal district court judges and four federal magistrates. The Minneapolis federal courthouse is home to six federal district court judges and two magistrate judges. Additionally, the courthouses in Duluth and Fergus Falls each house a magistrate judge (unless there is a vacancy). Further, a magistrate judge currently sits in Bemidji as well (given the significant federal case traffic from the nearby Red Lake Indian Reservation); however, there is no federal courthouse facility in Bemidji. There are five federal bankruptcy judges in Minnesota as well; two are seated in St. Paul and three are seated in Minneapolis.

District court judges are on the frontline of the federal criminal and civil justice systems. Federal district court serves as the court of general and original jurisdiction for most federal matters. A court of general jurisdiction is one that may handle all legal matters, including civil and criminal cases. A court of original jurisdiction is one in which cases are first heard and considered. Federal district judges are known as “Article III judges” as they are afforded protections under Article III of the Constitution—namely, appointment for a life term, salary protections, and forced removal from office only through impeachment. District judges preside over federal civil and criminal trials and supervise federal grand juries. The workload of federal district judges can vary considerably from one judicial district to another. Normally, as a district's caseload increases, Congress will respond by appropriating funding for additional judicial positions. However, politics can sometimes get in the way as a Congress dominated by one party may not wish to give a president from the other party an opportunity to expand the federal judicial bench with appointees who presumably share the president's legal philosophy.

Another mechanism for addressing workload concerns of federal district judges is the magistrate judge. A federal magistrate judge has the power to conduct misdemeanor-level criminal trials, as well as various routine preliminary hearings, including initial appearances and the issuance of subpoenas and warrants. While district judges are appointed by the President, confirmed by the Senate, and can serve for life, magistrate judges are appointed by district court judges. Full-time magistrates can serve for up to two consecutive 8-year terms. Part-time magistrates may serve up to 4-years per term. The position of magistrate judge was created in 1968 as a way to lighten the workload of federal district judges. In the United States, there are over 500 full-time and 45 part-time magistrate judges (Mays, 2012).

Table 8.1. Types of Cases Heard in Federal and State Courts

Federal Grand Juries

A grand jury is a panel of citizens called to grand jury duty who consider the facts and evidence of a criminal case and determine whether criminal charges should be filed. They are different from a trial jury in that they do not determine whether or not someone is guilty. Rather, they simply determine whether or not sufficient evidence exists, based on probable cause, for someone to be charged and tried with a crime. If a grand jury determines that there is enough probable cause for someone to be charged, they issue a charging document called an indictment, also called a “true bill.” If they determine that there is not sufficient evidence for someone to be charged with a crime, they issue a “no bill.” In the Minnesota criminal justice system, grand juries are used for only for certain types of cases. In particular, Minnesota grand juries are utilized in cases involving police officer use of deadly force and for crimes in which the maximum sentence is life in prison (Brown, 2014).

At the federal level, grand juries are used much more routinely than is the case under Minnesota state law. Indeed, federal grand juries are relied upon to secure charges in almost all felony-level offenses. Federal misdemeanor charges come in form of an information. Likewise, informations are used as charging documents in some federal felony cases in which a suspect would like to resolve the case quickly and plead guilty. However, in the majority of federal felony cases, indictments must be issued. This is consistent with the constitutional requirement under the 5th amendment, which reads in part “

no person shall be

held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a grand jury

...”.

Federal grand juries consist of 23 citizens drawn for jury duty from the judicial district in which the grand jury is impaneled. A quorum is required for the grand jury to conduct business. A quorum is defined by 16 of the 23 jurors being present (U.S. Courts, n.d.). For an indictment to be issued, a minimum of 12 grand jurors must vote in favor of a true bill. As with state grand juries, the work of a federal grand jury, and its deliberations, are secret. Indeed, it is a criminal offense to leak grand jury information—that is, evidence or testimony considered or presented before the grand jury and any information about the deliberations of grand jurors regarding a particular case (U.S. Courts, n.d.).

U.S. Probation and Pretrial Services

An important component of the United States Courts is the office of U.S. Probation and Pretrial Services. The work of U.S. Probation and Pretrial Services officers includes investigating and reporting on the background of the accused appearing in federal court so that judges can make appropriate bail determinations; investigating and reporting on compliance with court-ordered conditions of release for those awaiting trial or for those convicted of crimes and serving sentences of probation; and assisting defendants and convicts in finding opportunities within the community for work and treatment to improve their lives and facilitate productive assimilation back into society (U.S. Probation and Pretrial Services, 2002).

Federal probation officers have been working in Minnesota since 1930. The number of federal probation officers grew in Minnesota from one in 1930 to six officers in 1970. The number of officers grew further as the state population and federal caseload grew. There were 14 federal probation officers in the mid-1980s and 28 by the early 1990s. By 2010, there Probation and Pretrial Services for the District of Minnesota had over 50 officers and nearly 30 support staff (U.S. Probation and Pretrial Service, n.d.).

The work of probation officers at the state and federal levels can be dangerous. Because of this, many states permit their probation officers to carry firearms in the course of official duties. As outlined in

Chapter Four

, the state of Minnesota does not permit probation officers to carry firearms as they are not licensed peace officers. Although state probation officers in Minnesota are unarmed, federal officers employed by U.S. Probation and Pretrial Services are permitted to carry firearms. Title 18, Sections 3603 and 3154, of the United States Code permits U.S. probation and pretrial services officers to carry firearms if approved

by the federal judicial district in which they work, and the District of Minnesota does so approve.

U.S. Attorney for the District of Minnesota

The Office of United States Attorney in every federal judicial district in the United States shares the same responsibilities: the prosecution of criminal cases brought by the federal government; the litigation and defense of civil cases in which the United States is a party; the handling of criminal and civil appellate cases before the United States Courts of Appeals; and the collection of debts owed the federal government that are administratively uncollectable (Bumgarner, et al., 2013). The United States Attorney for the District of Minnesota and in the other 93 judicial districts come under the organizational umbrella of the U.S. Department of Justice and the U.S. Attorney General as the head of the department. Consequently, individual offices of United States Attorneys must align their own missions with the priorities of the U.S. Justice Department. The Justice Department explains the purpose for its existence in the form of several broad mission goals (Bumgarner, et al., 2013):

- enforce the law and defend interests of the US according to the law;

- ensure public safety against threats, foreign and domestic;

- provide federal leadership in preventing and controlling crime;

- seek just punishment for those guilty of unlawful behavior; and

- ensure fair and impartial administration of justice for all Americans.

Ultimately, the work of the U.S. Attorney's Office in Minnesota, and that of all Justice Department agencies, must comport with these above goals.

The U.S. Attorney's Office in Minnesota has existed since 1849 when Congress established Minnesota as a territory and federal judicial district (Office of United States Attorney, 2015). The U.S. Attorney for any of the 94 judicial districts, including Minnesota, is appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate. Given the appointment process, most U.S. Attorneys have some political connections to the party of the President in power. However, they also typically have risen through the ranks as career federal or local prosecutors. Prosecutorial experience is an important consideration for appointment.

While U.S. Attorneys are appointed and serve at the pleasure of the President, most of the work is done by career staff attorneys known as assistant U.S. attorneys. Assistant U.S. attorneys (AUSAs) are the line-level prosecutors in the U.S. Attorney's Office. Nationwide, there are nearly 6,000 AUSAs. However, Minnesota employs only a little over 50 AUSAs.

The pace of work for AUSAs is robust—especially given the complex nature of many federal cases. In fiscal year 2010, U.S. Attorney offices around the country filed nearly 61,529 criminal cases involving nearly 84,000 defendants. Approximately 39% of the cases were immigration-related, 21% were narcotics-related, and 20% involved violent crime charges. The conviction rate in federal cases is consistently above 90%, with over 80% of those convicted receiving federal prison time (DOJ, 2014). In the District of Minnesota, during fiscal year 2013, 226 new criminal cases were filed involving 305 criminal defendants. Additionally, there were 396 cases pending against 621 defendants at the beginning of fiscal year 2013 (DOJ, 2014).

The conviction rate was higher than the national average in fiscal year 2013. A total of 389 defendants in Minnesota either pled guilty or were found guilty at trial; only 2 defendants were found not guilty. Cases against a total of 31 defendants were dismissed (DOJ, 2014).

The U.S. Attorney's Office in Minnesota consists of four divisions:

- Criminal Division

- Civil Division

- Appellate Division

- Administrative Division

The Criminal Division is the largest division of the U.S. Attorney's Office. It consists of 40 assistant United States attorneys. The Criminal Division itself is broken into four distinct sections (Office of United States Attorney, 2015). The sections are:

- Fraud and Public Corruption—includes cases relating to mail fraud, wire fraud, bank fraud, mortgage fraud, environmental crime, and bribery.

- Major Crimes and Priority Prosecutions—includes cases related to terrorism, cybercrime, human trafficking, child exploitation, immigration violations, bank robbery, federal program fraud, and crimes in Indian Country.

- OCDETF and Violent Crimes—includes cases which emerge from the Organized Crime and Drug Enforcement Task Force (OCDETF), repeat federal offender crimes involving guns, gangs, and drugs, and other criminal organization cases.

- Special Prosecutions—focuses on cases which span the other three areas, but are especially long-term and resource-intensive in nature.

The Civil Division focuses on civil cases relating to federal program fraud, fair housing and employment, environmental regulations, civil rights, and

asset forfeiture. The 11 assistant U.S. attorneys in the Civil Division in Minnesota are also responsible for defending the United States government in cases involving the Federal Tort Claims Act, employment laws, immigrations laws, and Constitutional claims. The Appellate Division monitors cases going to, and coming out of, the Eight Circuit Court of Appeals and evaluates those decisions for precedent and other implications. Finally, the Administrative Division is responsible for providing support services to the Office of United States Attorney, including human resources, information technology, budget and procurement, facilities management, and other areas (Office of United States Attorney, 2015).

Minnesota's Federal Law Enforcement Community

The federal executive branch of government is organized into regions across the United States. Minnesota is a part of Region 5, which also includes Wisconsin, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, and Ohio. For large federal agencies, one will typically find a full-fledged field office in Minneapolis or St. Paul. For smaller federal agencies, the nearest field office is likely located in Chicago and the presence in Minnesota comes in the form of smaller, resident offices which answer to the regional office in Chicago.

Nationwide, there were 120,000 federal law enforcement officers in 2008. This is the most recent year that a census of federal law enforcement officers was tabulated by the Bureau of Justice Statistics. Of the 120,000 federal officers, approximately 37% were in jobs which primarily involved criminal investigative responsibilities, 21% were in positions primarily consisting of police patrol responsibilities, and 15% were engaged in immigration and border inspection job functions (Reaves, 2012).

Within the state of Minnesota, there were 1,160 federal law enforcement officers in 2008. Of these, 376 officers were engaged primarily in criminal investigative responsibilities. Another 127 officers were primarily engaged in police patrol responsibilities. Inspection-related duties was the job focus of 212 officers. The remaining federal law enforcement officers in Minnesota were engaged in other duties, including court operations, physical security, corrections, and other functions (Reaves, 2012). Minnesota had a federal law enforcement officer to citizen population ratio of 22 per 100,000 residents. This is in contrast to a high of 130 officers per 100,000 citizens for the state of New Mexico and a low of 9 officers per 100,000 citizens for the states of Iowa and Wisconsin (Reaves, 2012).

The number of federal law enforcement officers in Minnesota has grown gradually over the years. From 2002 to 2008, the number of federal officers and agents in Minnesota expanded by 19%. At the same time, the population of the state also grew, so the ratio of federal officers to Minnesotans climbed only modestly. In 2002, Minnesota was home to 976 federal law enforcement officers (Reaves and Bauer, 2003). By 2004, the number of federal officers and agents working in Minnesota increased to 1,067 (Reaves, 2006). The ratio of federal law enforcement officers to Minnesota citizens, per 100,000, in 2002 and 2004 were 19 and 21, respectively. This represents a 16% increase in the density of federal officers within Minnesota from 2002 to 2008.

Table 8.2. Number and Job Function of Federal Law Enforcement Officers in Minnesota by Year

Federal Bureau of Investigation

The agency with the largest federal law enforcement presence in Minnesota is the Federal Bureau of Investigation, or FBI. The FBI's main field office in Minnesota is in Brooklyn Park, a suburb of Minneapolis, and is one of 56 FBI field offices around the country. However, the FBI also maintains resident offices with small numbers of special agents in the cities of St. Paul, Bemidji, Duluth, Mankato, St. Cloud, and Rochester. The Special Agent in Charge of the Minneapolis field office also supervises the resident offices in South Dakota (Rapid City, Aberdeen, Pierre, and Sioux Falls) and North Dakota (Bismarck, Minot, Grand Forks, and Fargo). Further, in response to escalating crime in the Bakken oil field region, the Minneapolis Division of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) announced plans in 2014 to open a permanent field office in Williston, North Dakota, which it went on to do. The oil boom created an influx of highly paid temporary workers living in sprawling “man camps” with limited spending opportunities and law enforcement oversight (Horwitz, 2014). Such conditions spawned a market for illicit drugs, prostitution, and sex trafficking, which, in

turn, attracted organized criminals and increased levels of violence, especially against women (Horwitz, 2014).

As federal law enforcement agencies go, the FBI is a relative new-comer, having not been created until the 20th century. The U.S. Department of Justice was created in 1870. However, the department did not have a detective bureau of its own. Instead, when it wanted to have a criminal investigation conducted, it had to borrow investigators from other agencies, such as the Secret Service, or hire private investigators such as the Pinkertons. By the turn of the 20th century, Congress became increasingly wary of expanding the investigative powers of existing federal agencies for fear of creating a national secret police organization. Consequently, laws were passed restricting the use of private detectives and the loaning out of special agents from the Secret Service to other government bureaus (Jeffreys-Jones, 2007). Congressman James Tawney from southern Minnesota was instrumental in passing these laws (Fox, 2003).

Having recognized a need for an investigative unit within the Department of Justice—particularly after the availability of investigators from other sources dried up due to the legislation mentioned above, Attorney General Charles Bonaparte elected to administratively create a detective unit within the Department of Justice in 1908. He did so by transferring in 9 ex-Secret Service agents and hiring an additional 25 people new to government service to become agents (DOJ, 2008).

In 1909, George Wickersham became Attorney General under newly elected President William Taft. Wickersham embraced the importance of a detective unit with the Department of Justice and secured permanent funding for the outfit. He named the unit the Bureau of Investigation. It wasn't until 1935, however, that the FBI director J. Edgar Hoover renamed the organization the Federal Bureau of Investigation, having finally secured statutory arrest and firearms authority in 1934 (Bumgarner, et al., 2013).

Today, the FBI continues to be a key agency within the U.S. Department of Justice. The agency employed 35,664 people in 2012, including 13,778 special agents 21,886 support staff.

The support staff includes professional positions such as crime and intelligence analysts, language specialists, forensic scientists, computer specialists, attorneys, and others (Bumgarner, Crawford, & Burns, 2013). The exact numbers of FBI agents in Minnesota is not publicly released, but the Minneapolis field office, along with its resident offices, is considered a “medium-sized” field office within the agency.

Prior to the 9/11 terror attacks in 2001, the FBI focused most of its resources and attention on violent crime, white collar crime, and government fraud. Indeed, the FBI has the broadest investigative jurisdiction of any federal agency, possessing authority to investigate over 200 federal crimes. However, after September

11, 2001, the FBI deliberately changed its investigative footing to focus much more attention on homeland security and counterterrorism. The FBI's stated investigative priorities are listed below. It is no accident that the first three priorities relate to protection of the United States from terroristic threats (FBI, 2015).

- Protect the United States from terrorist attack.

- Protect the United States against foreign intelligence operations and espionage.

- Protect the United States against cyber-based attacks and high-tech crimes.

- Combat public corruption at all levels.

- Protect civil rights.

- Combat transnational and national criminal organizations and enterprises.

- Combat major white-collar crime.

- Combat significant violent crime.

- Support federal, state, county, municipal, and international partners.

- Upgrade technology to successfully perform the FBI's mission.

The shift by the FBI toward homeland security and counterterrorism investigations is certainly as observable in Minnesota as it is anywhere else in the country. The FBI office in Minneapolis sponsors a very active Joint Terrorism Task Force (JTTF) consisting of FBI agents and law enforcement officers from a myriad of other federal, state, and local agencies. Counterterrorism investigations in Minnesota have gained national attention as many young men from the large Somali refugee population in Minnesota have sought to travel to Syria and Iraq to fight with the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS), which is in violation of federal law (see

Chapter Ten

).

Other Federal Law Enforcement Agencies

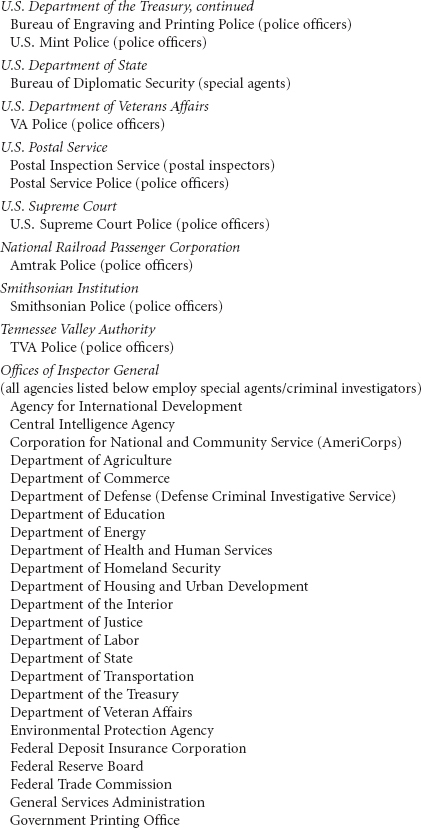

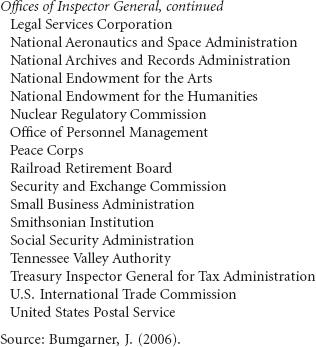

In addition to the FBI, the state and District of Minnesota is home to several other federal law enforcement agencies. Many Americans are unaware of just how many federal law enforcement agencies exist. Due to television, cinematic, and news media portrayals, they might be aware of the FBI, Secret Service, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (ATF), and the Naval Criminal Investigative Service (NCIS). Few have ever heard of the Department of Agriculture's Office of Inspector General or the Environmental Protection Agency Criminal

Investigation Division. In fact, there are dozens of federal agencies which possess law enforcement authority (defined as the authority by employees to carry firearms and make arrests for violations of federal law).

Figure 8.2. Federal Law Enforcement Agencies and Officers

In addition to the FBI, the U.S. Department of Justice houses several key federal law enforcement agencies. These include the U.S. Marshals Service, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (ATF). As noted earlier, the U.S. Marshals Service functions as the federal government's sheriff's department. It is responsible for court security, custody and transportation of federal prisoners prior to serving prison sentences, serving court processes, and apprehending federal fugitives. The DEA is the agency responsible for investigating violations of our nation's drug laws, which are codified in Title 21 of the United States Code.

The ATF was transferred to the Justice Department from the Treasury Department in 2003 as a result of the Homeland Security Act of 2002. The ATF has primary jurisdiction in federal bombing cases, unless the event is considered terrorism-related, in which case the FBI has primary jurisdiction. The ATF also investigates federal firearms violations, which are articulated in the Gun Control Act of 1968 and its amendments.

Before the terror attacks on September 11, 2001, the two cabinet-level departments primarily known for their federal law enforcement assets were the Department of Justice and the Department of Treasury. Historically, treasury agents were as remarkable in the eyes of the public as FBI agents, the former of which included federal sleuths such as Eliot Ness. The Treasury Department had included agencies such as the Secret Service, U.S. Customs, ATF, and the

Internal Revenue Service (IRS). However, with the Homeland Security Act of 2002, most Treasury law enforcement agencies other than the IRS were relocated to other departments. As already noted, the ATF was moved to the Justice Department. The Secret Service and U.S. Customs both were moved to the newly created Department of Homeland Security. Through the reorganization, the investigative components of the U.S. Customs Service and the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) were combined to form the investigative branch of the Bureau of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE)—which is today known as Homeland Security Investigations (HSI). The uniformed branches of Customs and INS, including the U.S. Border Patrol, were combined to become the Bureau of Customs and Border Protection (CBP). All of these agencies have offices in Minnesota. In fact, ICE-HSI is commonly the lead agency on human trafficking investigations—many of which have resulted in high-profile criminal prosecutions within Minnesota (see

Chapter Ten

).

Another Department of Homeland Security agency maintaining a presence in Minnesota is the U.S. Secret Service. The Secret Service was created as a Treasury Department agency in 1865 to confront the widespread problem at the time of counterfeit currency and fraud committed against the U.S. Government. Today, the Secret Service is also known for dignitary protection—particularly the U.S. President, U.S. Vice-President, and their families. The Secret Service is also responsible for investigating computer/electronic transfer crimes and credit card fraud. Finally, given its physical and personal security expertise, the Secret Service has been made the lead agency in protecting national special security events. These large-scale, high-profile events include the Super Bowl and national political party conventions (see

Chapter Ten

).

As mentioned previously, the IRS was one agency which did not transfer out of the Department of the Treasury. The history of the IRS goes to the year 1919 when an intelligence unit was created within the Treasury Department. This unit was responsible for investigating tax evasion. The intelligence unit, over time, would see its name change but not its mission. Today, it is known as the Criminal Investigation Division (CID) of the Internal Revenue Service and it has exclusive jurisdiction to investigate violations of Title 26 (which articulates federal tax and financial crimes).

Some of the truly under-heralded, but very important, members of the federal law enforcement community are the Offices of Inspector General (OIGs). OIGs can be found in every federal cabinet-level department, every major independent agency, and in many other federal independent agencies. The mission of the Offices of Inspector General is to prevent and detect fraud, waste, and abuse in federal programs under the auspices of their parent federal agency or department (Bumgarner, 2014). Historically, OIG special agents had varying

degrees of law enforcement authority, depending on specific OIG. However, the Homeland Security Act of 2002 granted uniform firearms and arrest authority across the majority of OIGs. Nationwide, there are a little over 2,000 OIG special agents. Dozens of OIG special agents from several agencies are located within the state of Minnesota. Crimes commonly investigated by OIGs include program fraud, contract fraud, collusion, bribery, threats, assaults, thefts, embezzlement, and conspiracy.

Perceptions of Federal Law Enforcement

All of the agencies above, and many others on the list in

Figure 8.2

maintain offices of varying sizes in Minnesota—primarily in the Twin Cities of St. Paul and Minneapolis—but also in other regional centers of the state. The federal law enforcement community works with state and local law enforcement throughout Minnesota to accomplish the common goal of abating criminality within the state. To that end, cooperation between federal agents and state and local police officials is certainly a must. And yet, in Minnesota and elsewhere, there has historically been tension between federal law enforcement—especially the FBI—and everybody else in the law enforcement community.

In an effort to begin to gauge the relationship between local and federal law enforcement officials in Minnesota, a small pilot study was conducted in 2011 to assess among local law enforcement officers their knowledge and opinions about federal law enforcement. A total of 63 police officers and sheriff deputies at five Minnesota agencies participated in a survey (Bumgarner, 2011). Seventy-nine percent of these officers had at least some experience working with federal law enforcement officers.

The survey instrument was designed to illicit attitudinal/opinion measures along various constructs, including the appropriate mission of federal law enforcement, the capabilities of federal law enforcement officers, and general impressions and favorability toward federal law enforcement. The survey results suggested that, in the aggregate, officers possessed some misgivings about the reach and scope of federal law enforcement. But just as true, they expressed relatively high levels of confidence in the abilities of federal agents to perform their jobs.

With regard to questions relating to the mission and scope of federal law enforcement, a plurality of respondents tended to view the federal government as too large and too over-reaching. For example, in response to the statement “The federal government is too big,” approximately 40% agreed or strongly agreed, while only 17% disagreed or strongly disagreed. There was also a consistent chorus in support of the idea that states and localities should play the lead in most criminal and public policy matters. A full 60% of the surveyed officers

agreed or strongly agreed with the statement “Most public policy issues should be handled by state and local government agencies,” while about 5% disagreed or strongly disagreed.

Regarding the capabilities of federal agents, there was some good news for federal law enforcement. The idea of a federal agents being stuffy, inflexible, and lacking common sense or good judgment is well-represented in the popular culture. The movie

Die Hard

was just one of countless cinematic productions over the years that have shown federal agents acting in ill-advised, immature, rigidly by-the-book, or otherwise unsophisticated and unintuitive manner—which always serves to simply make the job of the real cops that much harder. However, less than 10% of the officers surveyed here agreed with the notion that federal agents have no street smarts, and only one officer taking the survey was willing to agree with the explicit declaration that federal agents lack common sense. Finally, federal law enforcement tended to fare well with respondents' general perceptions. A full 52% of respondents recorded a favorable or extremely favorable view of federal law enforcement. About 5% of the respondents reflected a generally unfavorable or extremely unfavorable view.

This Minnesota-specific study lacked experimental controls and surveyed only a small number of officers. Therefore, there are limits to the conclusions one can draw from the study. But in so far as the officers surveyed in the study were concerned, there was some good news to be had for the federal law enforcement community in Minnesota. The notion that federal law enforcement has to overcome stereotypes about poor judgment and incompetence was largely not supported by the survey results. By and large, local police officers and deputies in the study expressed confidence in the law enforcement abilities of federal agents. What's more, local officers who had experience working with federal agents in Minnesota tended to reflect favorable views of the agents who helped constitute those experiences. Minnesota officers who participated in the study tended to like and respect the federal agents they have had occasion to work with, but remain somewhat unsatisfied with a lack of cooperation and mission encroachment at the organizational level of federal agencies. An implication for the federal government seeking stronger ties with local law enforcement in wide array of criminal investigation and homeland security arenas is that federal agencies might try to “get out of the way” (institutionally) as much as possible and let the individual, collaborative, and competent federal agents working for them be the face of the federal government to their local law enforcement partners.

Effective law enforcement—particularly as it relates to homeland security—requires cooperation and coordination across all levels of government. Law enforcement agencies must have confidence in their partner organizations and, to the extent possible, avoid the distractions of interagency and intergovernmental

squabbling. Among officers and agents, respect for one another as professionals and respect for the organization and mission to which the professionals belong likely go a long way toward reducing counterproductive infighting.

Federal Corrections in Minnesota

The U.S. Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) is an agency within the U.S. Department of Justice and is responsible for designing, operating, and maintaining the federal correctional system. The BOP employs over 39,000 people and supervises the prison sentences of 208,000 federal inmates. The BOP operate 148 facilities nationwide, with security conditions ranging from minimum security to high security (Federal Bureau of Prisons, 2015).

Minnesota is the home to four facilities operation by the Federal Bureau of Prisons (also see

Chapter Four

). The facilities are:

- Duluth Federal Prison Camp (minimum security)

- Sandstone Federal Correctional Institute (low security)

- Waseca Federal Correctional Institute (low security)

- Rochester Federal Medical Center (administrative security)

The Duluth Federal Prison Camp houses 759 male inmates. As a minimum security facility, the Duluth Federal Prison Camp utilizes dormitory housing for inmates. There is no perimeter fencing to secure inmates at the facility. And, with minimum security camps, the staff to inmate ratio is relatively low. The focus with minimum security federal facilities is on providing inmates with opportunities for work and programs to improve life-skills and occupational readiness (Federal Bureau of Prisons, 2015). The Duluth Federal prison camp is one of seven minimum security federal facilities in the United States.

The Sandstone and Waseca federal correctional institutes, as low security facilities, do have some accoutrements of prison. For example, low security facilities managed by the Bureau of Prisons include double-fenced perimeters. They also have a larger staff to prisoner ratio than minimum security facilities. The life of an inmate is more structured and participation in work and programming is expected. The Sandstone Federal Correctional Institute houses 1,310 male inmates. The Waseca Federal Correctional Institute houses 974 female inmates. Interestingly, there are 35 low security federal correctional institutes in the United States and two of them are in Minnesota (Federal Bureau of Prisons, 2015).

Finally, Minnesota is home to the Rochester Federal Medical Center. This facility is one of six medical referral centers managed by the U.S. Bureau of Prisons. The Rochester Federal Medical Center houses 800 male inmates. The facility

is located on the grounds of a former state hospital. The center delivers to inmates specialized medical and mental health services. Notable inmates in the past include former televangelist Jim Bakker, political activist Lyndon LaRouche, and Sheikh Omar Abdel Rahman, the latter of whom was sentenced to life in prison for the 1993 bombing of the World Trade Center in New York (Walsh, 2010).

The federal government of the United States, as sovereign government sharing power with the states, maintains a criminal justice apparatus of its own. The federal government's criminal justice presence is visible in every state of the union, including Minnesota. Within the federal judicial district of Minnesota, the federal government operates out of four courthouses, four correctional facilities, and several law enforcement agencies. Cooperation, informed by respect, between federal, state, and local criminal justice authorities is essential for delivering on the promise of a secure homeland, justice for crime victims, and safety for the general public.

Key Terms

Article III Judges

Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (ATF)

Bureau of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE)

Circuit Court of Appeals

Charles Bonaparte

Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA)

Enumerated Powers

Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI)

Federal Bureau of Prisons

Federal Correctional Institute (Low Security)

Federal Prison Camp (Minimum Security)

Fifth Act of Congress

General Jurisdiction

Grand Jury

Homeland Security Investigations (HSI)

Information

Indictment

Internal Revenue Service (IRS)

Joint Terrorism Task Force (JTTF)

Judiciary Act of 1789

Necessary and Proper Clause

Office of Inspector General (OIG)

Organized Crime and Drug Enforcement Task Force (OCDETF)

Original Jurisdiction

Tariff Act of 1789

United States Attorney

United States District Court

United States Marshal

United States Secret Service

Selected Internet Sites

Discussion Questions

- What role, if any, should the federal government have in policing general crimes commonly addressed by local law enforcement? Does the expansion of federal criminal laws give rise to concerns about a national police force?

- Given the FBI's many criminal investigative responsibilities, should the United States create a new federal agency which focuses exclusively on counterterrorism?

- Many scholars and activists have raised concerns about federal prison sentences and their tendency to be longer than sentences imposed at the state level. Is it appropriate that federal prosecutions are sometimes pursued instead of state prosecutions in order to secure tougher punishments for offenders?

- There are dozens of federal law enforcement agencies with firearms and arrest authority. Are there too many federal law enforcement agencies in existence today? Should many of these agencies be consolidated? Should some of these agencies be eliminated altogether? Explain.

- It is currently a federal felony to possess any amount of marijuana. And yet, many states have decriminalized marijuana in their own state statutes. Should federal law be amended to permit the legal use of marijuana? If not, should federal prosecutions continue even in states that have chosen to legalize marijuana?

References

Bumgarner, J. (2014). Federal law enforcement In J. Albanese (Ed.)

Encyclopedia of Criminology and Criminal Justice

. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Bumgarner, J., Crawford, C., & Burns, R. (2013).

Federal law enforcement: A primer.

Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press.

Bumgarner, J. (2011). “Exploring the Intersection of Policing and Federalism: Peace Officer Perceptions of American Federal Law Enforcement,” presented at the Academy of Criminal Justice Sciences, Toronto, ON, Canada.

Bumgarner, J. (2006).

Federal agents: The growth of federal law enforcement in America.

Westport, CT: Praeger.

Calhoun, F. (1989).

The lawmen: United States marshals and their deputies

. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2015).

Today's FBI Facts & Figures 2013–2014

. Washington DC: FBI Office of Public Affairs.

Fox, J. (2003).

The birth of the Federal Bureau of Investigation

. Washington, DC: Office of Public/Congressional Affairs.

Jeffreys-Jones, R. (2007).

The FBI: A history

. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Madison, J. (1788). Alleged dangers from the powers of the Union to the state governments considered [Federalist 45].

Independent Journal.

January 26.

Mays, C.L. (2012).

The American courts and the judicial process

. New York: Oxford University Press.

Reaves, B. (2012).

Federal law enforcement officers, 2008

. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Reaves, B. (2006).

Federal law enforcement officers, 2004

. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Reaves, B. and Bauer, L. (2003).

Federal law enforcement officers, 2002

. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Saba, A. (2003). U.S. customs service: Always there ... ready to serve.

U.S. Customs Today

. February.

U.S. Coast Guard. (2002).

U.S. coast guard: An historical overview.

Washington, DC: USCG Historian's Office.

U.S. Courts. (n.d.)

Handbook for federal grand juries

. Washington, DC: Administrative Office of the United States Courts.

U.S. Department of Justice. (2014).

United States Attorneys' annual statistical report

. Washington, DC: U.S. DOJ.

U.S. Department of Justice. (2008).

The FBI: A centennial history, 1908–2008

. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.