There are those who write history. There are those who make history. I don’t know how many of you would be able to write a history book. But you are certainly making history, and you are experiencing history. And you will make it possible for the historians of the future to write a marvelous chapter.1

—Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., May 6, 1963, Mass Rally at St. Luke’s Church, Birmingham, Alabama

On the “hot and muggy” morning of Monday, May 6, when the temperature rose to ninety degrees, the young people of Birmingham returned to center stage.2 James Bevel made certain of that. He flooded the local African- American high schools with fliers that read: “Fight for freedom first then go to school. Join the thousands in jail who are making their witness for freedom. Come to the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church. … It’s up to you to free our teachers, our parents, yourself and our country.”3

Bevel’s plea worked. Students roamed through the halls of Parker High School singing the word “freedom” and then filed out past the principal informing him, “Gotta GO, Mister Johnson, gotta GO.”4 At one school, as reported in the Birmingham News, only 87 students out of 1,339 stuck around.5 Instead, the students went to the church. Their playful manner suggested that the students did not realize just how momentous their actions would be that day. And this time the children did not march alone. The adults joined them.

Dick Gregory, a nightclub comedian and political activist, led the first march. Gregory related, “I arrived [in Birmingham] at 11:30 A.M. on a Monday, and an hour and a half later I went to jail with more than eight hundred other demonstrators.”6 Wearing a gray Italian suit and carrying a sign that said “Everybody wants freedom,” Gregory ushered nineteen young people out of the church. They sang, “I ain’t scared of your jail ‘cause I want my freedom, want my freedom.”

Police Captain George Wall, wearing a World War I helmet, confronted Gregory and asked him if he was leading the march. The comedian said he was. Wall then explained to him the laws they were violating by marching. “‘Do you understand?’ asked Captain Wall. “‘No I don’t’” replied the comedian. When Gregory refused to disperse, Wall first announced through the bullhorn, “Dick Gregrory says they will not disperse,” and next, “Call the wagon.”7

While some of Gregory’s companions walked and others snake-danced into waiting police vans, two other groups of marchers bolted from the church. That was just the beginning. As The New York Times reported, “… and for the next hour, they kept coming in groups of 20, 30, 40 and 50.”8 King greeted the marchers as they left the church and urged them to be nonviolent. “The world is watching you,”9 he told them.

The crowds on the street cheered as the young people paraded, got arrested, and were driven off in police vehicles. Heading for jail, the kids continued to sing freedom songs as they beat out rhythms on the sides and floors of the buses. Meanwhile, Bull Connor, in his straw hat, egged the protesters on, saying, “All right, you-all send all them on over here. I got plenty of room in the jail.”10

Waves of protesters emerged from the church. Police arrested some immediately, others after they kneeled on the sidewalk to pray, and still others as they reached the far end of Kelly Ingram Park. Some marchers started in the downtown areas. They too were immediately arrested. And though three red pumper trucks stood nearby, the hoses stayed dry.

The impact was overwhelming. Police hauled one thousand people off to jail that Monday.11 The parents had decided they could no longer stand on the sidelines. Adults counted for half of those participating in the marches that day. With six hundred grown-ups taken to jail, the demonstrations truly became a multigenerational experience within the African-American community of Birmingham.12 One historian stated that May 6 was “the largest single day of nonviolent arrests in American history.”13 After five weeks of demonstrations, Connor had arrested 2,425 marchers.14 The jails were filled.

With thousands in attendance Monday evening, the mass rallies had to be held at four churches. Abernathy excited the crowd at one gathering with these words: “Day before yesterday we filled up the jail. Today we filled up the jail yard. And tomorrow when they look up and see that number coming, I don’t know what they are gonna do.”15 King made his rounds to each house of worship and delivered these dramatic words to the crowd at St. Luke’s Church:

More Negotiating

As demonstrations shook Birmingham, negotiations continued. Burke Marshall met for two and a half hours in the morning with King. He tried to convince King to call off marches and wait until the new Boutwell government took over. Apparently, Marshall got nowhere with his pleas.

There were also meetings between more moderate whites such as Sidney Smyer, a local business leader, and attorney David Vann, and black leaders including Shuttlesworth, Andrew Young, Lucius Pitts, and A. G. Gaston. These negotiations also accomplished little. The black participants deemed potential compromises put forth by the white group as insufficient.

For once, the black community had the advantage and they intended to use it. The unity reflected in both the dramatic marches and the mammoth rallies that energized the people and gave them a true power. In addition, leaders in the movement began to notice another important consequence of the demonstrations. Citizens, both black and white, stayed away from the center of the city, creating a highly effective boycott of downtown businesses. Andrew Young noted, “not only had black customers stopped shopping, but the daily demonstrations, the omnipresent police cars and sirens, and the anxiety and tension surrounding the situation were also keeping white customers away from downtown Birmingham.”17 The boycott became a strong weapon in the fight to integrate and bring equality to Birmingham. With the power of their neighbors behind them, African-American negotiators fought even harder for movement demands.

Mounting Pressure

Bull Connor was getting increasingly desperate and determined. With the jails filled, he hoped to control events using force and fear, so he brought in reinforcements. Governor George Wallace supplied Connor with 250 Alabama highway patrolmen armed with submachine guns, sawed-off shotguns, and tear gas. More officers from the state came later in the week. Police from surrounding cities and civilians acting as a posse brought in by Dallas County Sheriff Jim Clark joined the law-enforcement officers.

Connor also employed an armored car that looked very much like a tank. The vehicle had six wheels and gun turrets.

As the vehicle roamed the streets on Tuesday, a voice from the loudspeaker on top demanded that people disperse. Hostile white crowds gathered near Kelly Ingram Park, though police barricades kept them back. Connor set the tone for the day telling a New York Times reporter, “We’ve just started to fight, if that’s what they want. We were trying to be nice to them, but they won’t let us be nice.”18

Alabama Governor George Wallace started to become an ugly and threatening presence that hovered over Birmingham. The governor had made his views clear during his inaugural address back in January 1963 when he stated:

The phrase “communistic amalgamation” was a reference to integration of blacks and whites. Wallace spoke as a determined segregationist and in stating his willingness to pay “a hard price” even suggested that he would use violence in opposing the civil rights movement.

Referring to events in Birmingham, Wallace told the Alabama state legislature on Tuesday, May 7, “I am beginning to tire of agitators, integrationists, and others who seek to destroy law and order in Alabama” and that he would “take whatever action I am called upon to take [to restore order].”20 At the end of the day on Tuesday, Brigadier General Henry V. Graham, head of the Alabama National Guard, showed up in Birmingham, raising the possibility that martial law would be declared.

As the negotiations failed and as Connor and Wallace became even more threatening, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) arrived on the scene. As the name would suggest, members of this civil rights organization tended to be younger than the leadership of Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and more confrontational in their approach. In planning sessions that lasted all night on May 6, movement leaders from the SNCC and SCLC, including James Bevel, James Forman, and Dorothy Cotton, plotted a new strategy for the May 7 protest. Instead of the short march from the church leading to quick arrest and jailing, marchers would start in the downtown area with the intention of creating maximum chaos. The strategists aptly called the plan Operation Confusion. They hoped to sustain the boycott by disrupting downtown business and putting even more pressure on local businessmen. Given Connor, Wallace, and a steadfast African-American leadership, a classic and frightening confrontation threatened the day.

Tuesday Marches

Before the marches began on Tuesday, May 7, King appeared at a press conference where he announced, “Activities which have taken place in Birmingham over the last few days, to my mind, mark the nonviolent movement coming of age. This is the first time in the history of our struggle that we have been able, literally, to fill the jails.”21 Apparently, local Sheriff Melvin Bailey agreed when he confessed, “We’ve got a problem.”22 Only twenty-eight people were to be arrested in the course of the day’s activities.23 The jails were just too crowded.

The day’s events happened like this. Bull Connor’s police blocked all the streets that led downtown. Movement activities started at noon when small decoy groups left from the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church. This early starting time caught the police off guard as many were still at lunch. The children marched around the perimeter of the park and then returned to church. After one group came back, other children emerged. These maneuvers were a distraction for the real action. Also at noon, six hundred young demonstrators arranged in sixteen groups invaded downtown Birmingham from all directions. “Movement moms” and students from Miles College secretly drove into the city center and distributed signs from the trunks of strategically parked cars.24 As movement lawyer Len Holt described the scene: “The clock stuck noon. The students struck. Almost simultaneously, eight department stores were picketed.”25 Police tore up signs but made no arrests.

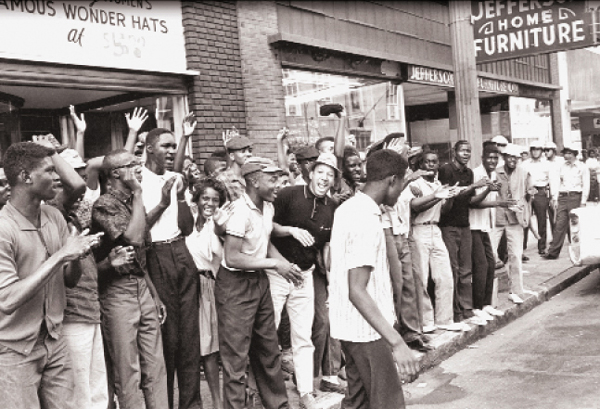

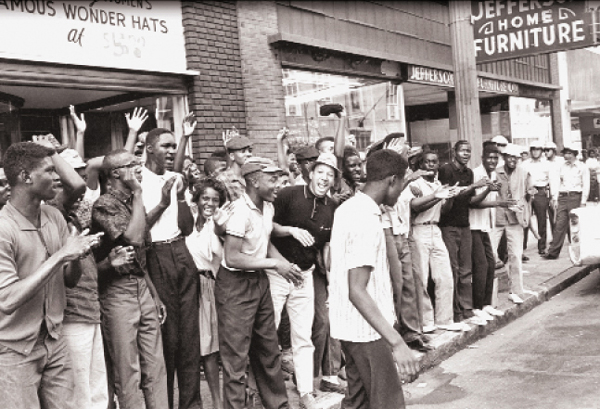

Image Credit: Associated Press

Young African-American protesters cheer and applaud as they stand along a sidewalk in Birmingham on May 7, 1963, during an anti-segregation demonstration.

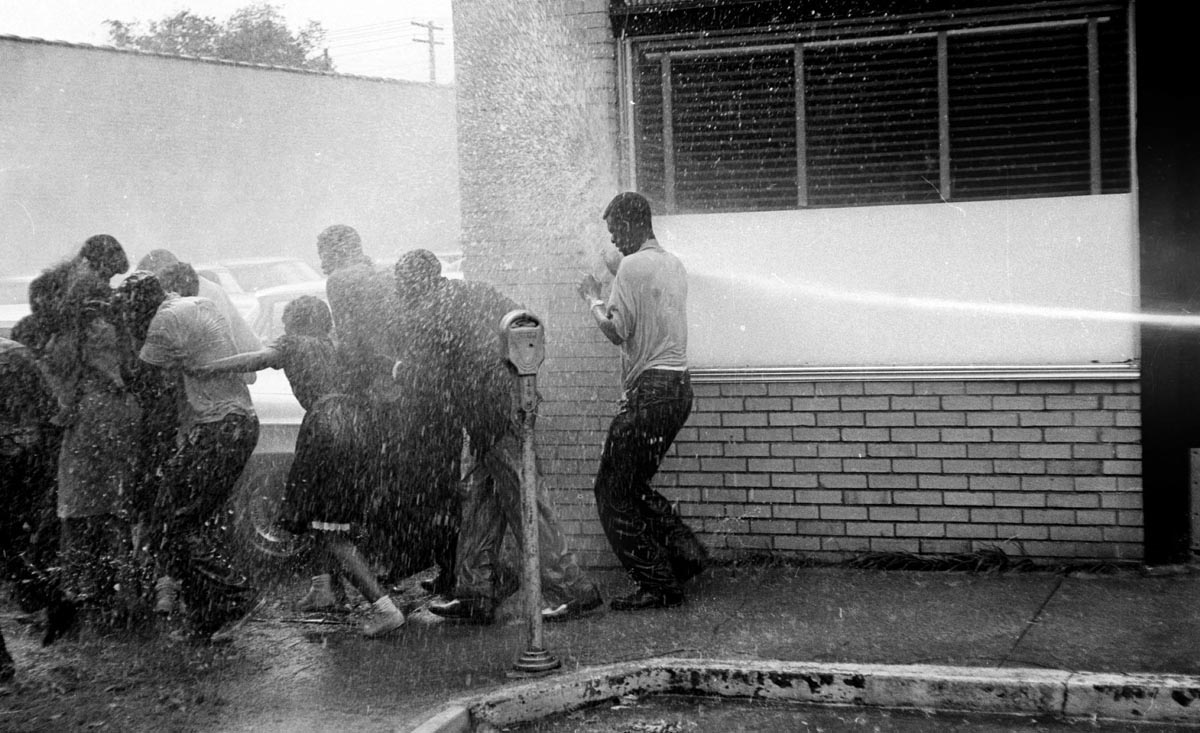

Image Credit: Alamy

Young protesters in Birmingham try to avoid a jet of water from a fire hose on May 7, 1963.

Meanwhile, back at the church, the door opened again and scores of protesters headed downtown in what Bevel called a “freedom dash.”26 Three thousand filled the streets, blocking traffic in the business district. As King described the scene:

The momentum continued through the afternoon as Fred Shuttlesworth initiated a second march into the heart of the city.

And then at 2:45 a “riot” occurred at Kelly Ingram Park. At least that’s what The New York Times called it. The violence started when black spectators “rained rocks, bottles and brickbats on the law-enforcement officials …”28 With the massive police presence and the threatening words of Governor Wallace fresh in people’s minds, the spiral of violence increased that afternoon. Fire hoses drove the people back. They quickly returned and again hurled stones at authorities. Police used their billy clubs liberally as they beat the onlookers in both nearby alleyways and within the park. Meanwhile, Bull Connor’s armored car prowled the streets. Again, there were white crowds all around the park, but police barricades kept them back. This is what Len Holt, movement activist, experienced when he stepped out of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church:

Again, SCLC leaders urged the crowd to be nonviolent. A. D. King walked through the park with a police megaphone announcing, “You’re not helping our cause.”30 King got little response. The struggle in Kelly Ingram Park lasted for an hour.31

Tuesday was also the day Birmingham authorities got even with Shuttlesworth. The reverend saw a kid in Kelly Ingram punch a cop and got worried that violence would escalate. While carrying a white flag, he led a group of three hundred young people who were in the park back to the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church. As he and the marchers went down an outside stairwell that lead to the church basement, he heard a fireman say, “Let’s put some water on the reverend.”32 Shuttlesworth later recalled:

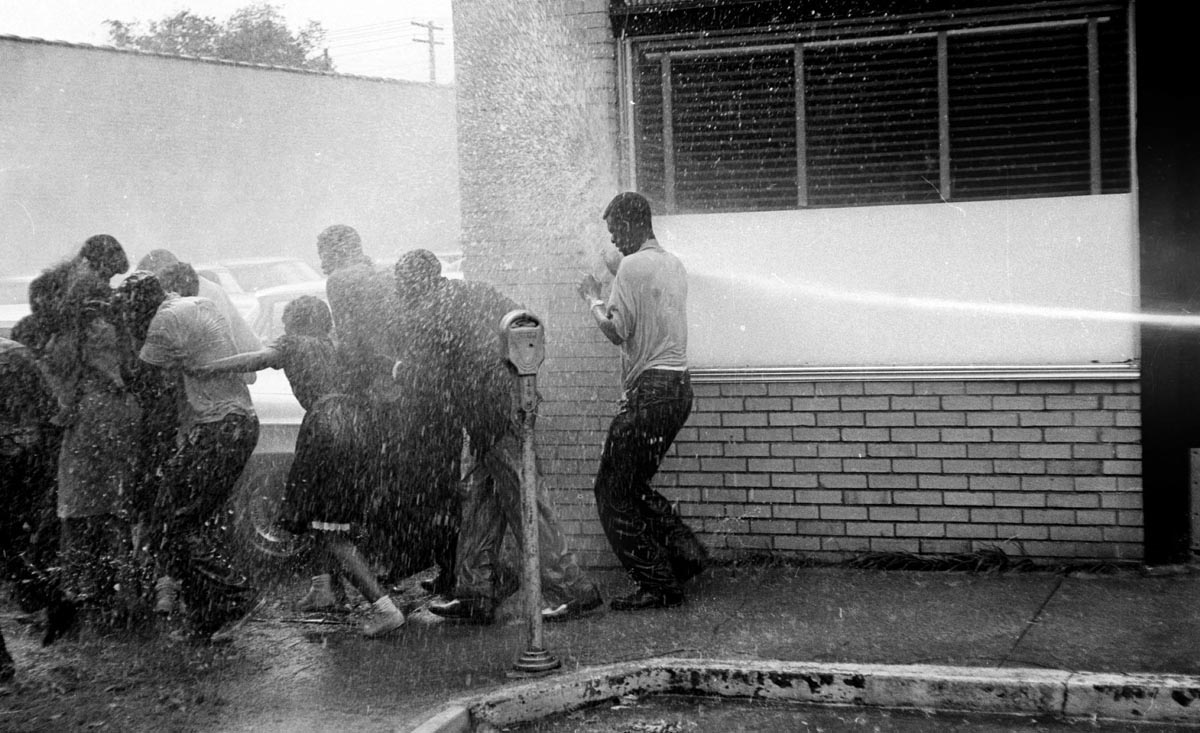

Image Credit: Black Star/Alamy

Firemen use hoses to hit protesters with high-powered streams of water in Birmingham.

The pressure of the water slammed the reverend against the church wall. He went immediately to the hospital. Commissioner Connor told a reporter he was sorry that he was not present. “I waited a week to see Shuttlesworth get hit with a hose. I’m sorry I missed it.” When informed that an ambulance had taken Shuttlesworth to the hospital, Connor stated, “I wish they’d carry him away in a hearse.”34 And in the midst of all the mayhem, negotiations continued.