5

Employment

ONE REASON that economic growth in the 1970s lost its power to reduce poverty was that many of the poor were without jobs. If one has no job, it makes no difference how much the economy grows. Poverty remains.

The relationship between unemployment and poverty is not new. But a new element was added to the unemployment problem beginning in the mid-1960s. The job market behavior and experience of one critical group in the struggle against poverty—young black males—changed radically. These changes constitute perhaps the most curious of the phenomena of the post-reform period (the late 1960s and thereafter) and certainly one of the most significant.

Jobs as the Magic Bullet

In the early days of OEO, it was thought that enough jobs would win the war against poverty. Some poor people would have to be given other kinds of help as well—the disabled, some of the elderly, perhaps single-parent mothers of young children—but for most of the working-aged population, making a job available was believed to be the answer.

The apostles of structural poverty soon did away with that view in intellectual circles, but popular and political faith in the power of jobs to solve the problem survived through the 1970s. Among many in both political parties, “jobs programs” have been seen as the obvious solution to poverty if only the nation were willing to commit itself fully.

In reality, the United States mounted an immense and sustained effort to provide jobs and job training during the post-reform period. “A Summary of the Federal Effort” at the end of this chapter provides more detailed information, but a few summary statistics will convey a sense of the magnitude of the effort and how suddenly it came upon the American scene.

Between 1950 and I960, the Department of Labor did virtually nothing to help poor people train for or find jobs. During the first half of the 1960s (1960–64), it spent a comparatively trivial half-billion dollars (in 1980 dollars) on jobs programs. From 1965 to 1969, as the Johnson initiatives got under way, a more substantial $8.8 billion was spent. In the 1970s through fiscal 1980, expenditures totaled $76.7 billion.1

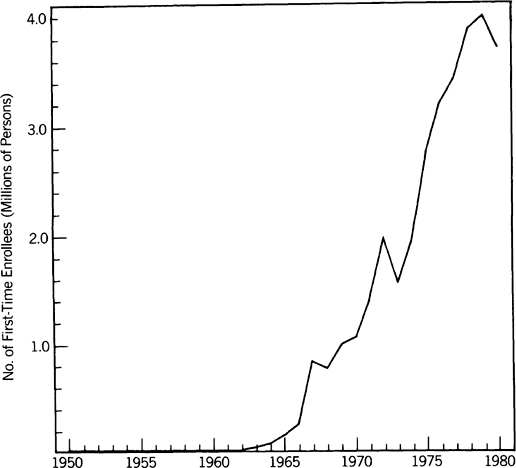

The numbers of persons involved are even more impressive than the dollars. Figure 5.1 shows the history of first-time enrollees in job training and employment programs administered by the Department of Labor. From the time that the first MDTA trainees were cycled through the program in 1962-63 through fiscal 1980, 32.6 million persons were reported to have enrolled in one of the Department of Labor’s programs. The number cannot be taken at face value—many of the program interventions were short or weak, many participants dropped out before they finished, and many in that figure of 32.6 million were repeaters. But the training and employment programs constituted an enormous national effort nonetheless. From 1965 to 1980, the federal government spent about the same amount on jobs programs, in constant dollars, as it spent on space exploration from 1958 through the first moon landing—an effort usually held up as the classic example of what the nation can accomplish if only it commits the necessary resources.2

Furthermore, the effort was concentrated on a relatively small portion of the population. From the beginning, the government jobs programs spent most of their money on disadvantaged youths in their late teens and early twenties. They were at the most critical time of their job development, they were supposed to be the most trainable, and they had the longest time to reap the benefits of help. In 1980, not an atypical year, 61 percent of the participants under CETA were 21 or younger, with a large but indeterminable additional proportion in their early twenties, and 36 percent were black.3 To give a sense of the concentration of effort among blacks, there were two black CETA participants (of any age) for every five blacks aged 16–24 in the labor force. In the same year (1980), there was one white CETA participant for each fourteen whites in the same age range.

First-time Enrollments for Work and Training Programs Administered by the Department of Labor, 1950–1980

Data and Source Information: Appendix table 4.

The contrast between the government’s hands-off policy in the 1950s and intervention in the 1970s is so great that it seems inconceivable that we should not be able to observe positive changes in the macroeconomic statistics. And yet in fact the macroeconomic statistics went in exactly the wrong direction for the group that was at the top of the priority list.

Black Unemployment Rates: A Peculiarly Localized Problem

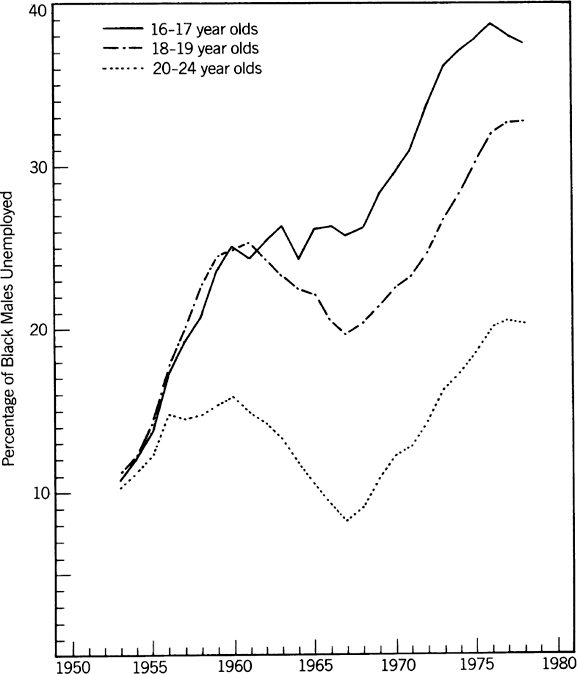

Let us first examine unemployment as officially defined4 among those who were the primary beneficiaries of the jobs-program effort, black youth at the entry point to the labor market. Figure 5.2 shows the employment history for three age groups within this population from 1951 (the first year for which we have an age breakdown by race) to 1980, using a five-year moving average plot to highlight long-term trends.5

The picture is a discouraging one. In the early 1950s, black youths had an unemployment rate almost identical to that of whites. In the last half of the 1950s, the rate of unemployment among young blacks increased. John Cogan has recently demonstrated that the increase may be largely blamed on the loss of agricultural jobs for black teenagers, especially in the South.6 As this dislocating transitional period came to an end, so did the increases in the unemployment rate for black youths. The rate stabilized during the early 1960s. It stabilized, however, at the unacceptably high rate of roughly a quarter of the black labor force in this age group. It appeared to observers during the Kennedy administration that a large segment of black youth was being frozen out of the job market, and this concern was at the heart of the congressional support for the early job programs.

Black unemployment among the older of the job entrants improved somewhat during the Vietnam War years, although the figures remained higher than one would have predicted from the Korean War experience. But in the late 1960s—at the very moment when the jobs programs began their massive expansion (see figure 5.1)—the black youth unemployment rate began to rise again, steeply, and continued to do so throughout the 1970s.

Unemployment Among Black Job Entrants, 16–24 Years Old: Five-Year Moving Average, 1951–1980

Data and Source Information: Appendix table 7.

If the 1950s were not good years for young blacks (and they were not), the 1970s were much worse. When the years from 1951 to 1980 are split into two parts, 1951–65 and 1966–80, and the mean unemployment rate is computed for each, one finds that black 20–24-year-olds experienced a 19 percent increase in unemployment. For 18–19-year-olds, the increase was 40 percent. For 16–17-year-olds, the increase was a remarkable 72 percent. If the war years are deleted, the increases in unemployment are higher still. Focusing on the age groups on which the federal jobs programs were focused not only fails to reveal improvement; it points to major losses. Something was happening to depress employment among young blacks.

The “something” becomes more mysterious when we consider that it was not having the same effect on older blacks. Even within the 16–24-year-old age groups, we may note that the relationship between age and deterioration seems to have been the opposite of the one expected. The older the age group, the less the deterioration. What happens if we consider all black age groups, including the ones that were largely ignored by the jobs and training programs? The year-by-year data are shown in the appendix, table 7. The summary statement is that, for whatever reasons, older black males (35 years old and above) did well. Not only did they seem to be immune from the mysterious ailment that affected younger black males, they made significant gains. We may compare the black male unemployment trends by age through the following figures:

| Age Group | Change in Mean Unemployment, 1951–65 to 1966–80 |

| 55–64 | –38.0% |

| 45–54 | –32.9% |

| 35–44 | –31.5% |

| 25–34 | –15.9% |

| 20–24 | +18.6% |

| 18–19 | +39.7% |

| 16–17 | +72.4% |

During the same fifteen-year period in which every black male age group at or above the age of 25 experienced decreased unemployment compared with the preceding fifteen years, every group under the age of 25 showed a major increase in unemployment. If it were not for the young, the overall black unemployment profile over 1950–80 would give cause for some satisfaction.

Black Youth versus White Youth: Losing Ground

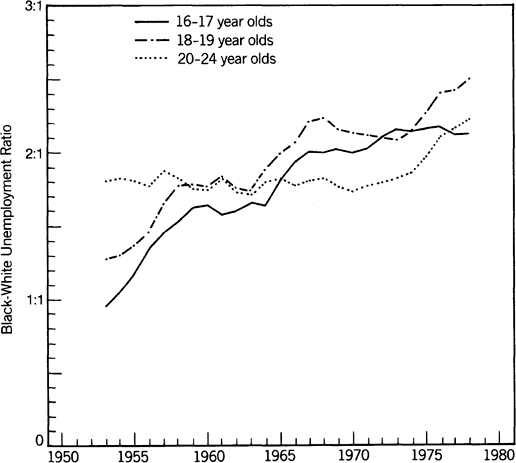

If young whites had been doing as badly, we could ascribe the trends to macro phenomena that affected everybody, educated or not, rich or poor, discriminated-against or not. But young blacks lost ground to young whites. This is apparent when we examine the ratio of black unemployment to white unemployment—the measure of the racial differential—for the job entrants, as shown in figure 5.3:

Black-White Unemployment Ratio Among Male Job Entrants: Five-Year Moving Average, 1951–1980

Data and Source Information: Appendix table 7.

The position of black youths vis-à-vis white youths worsened for all three groups. For teenagers, the timing was especially odd. From 1961 to 1965, for example, when there were virtually no jobs programs, the black to white ratio for 18–19 year-olds averaged 1.8 to 1. From 1966 to 1969, with a much stronger economy plus the many new jobs programs, the ratio jumped to an average of 2.2 to I.7 Without trying at this point to impose an explanation of why black youth unemployment rose so drastically from the late sixties onward, I note in passing that satisfactory explanations do not come easily. The job situation of young blacks deteriorated as the federal efforts to improve their position were most expensive and extensive—efforts not just in employment per se, but in education, health, welfare, and civil rights as well. Nor does it help to appeal to competition with women, to automation, to the decay of the position of American heavy industry, or any other change in the job market. These explanations (which may well explain a worsening job situation for unskilled workers) still leave unexplained why blacks lost ground at the height of the boom, and why young blacks lost ground while older black workers (who were hardly in a better position to cope with a changing job market) did not lose, and in fact gained, ground. The facile explanation—jobs for young blacks just disappeared, no matter how hard they searched—runs into trouble when it tries to explain the statistics on labor force participation.

The Anomalous Plunge in Black Labor Force Participation

“Labor force participation” is the poor cousin of unemployment in the news media. Each month, the latest unemployment figures are sure to have a spot on the network news broadcasts; if times are hard, the lead. Labor force participation is less glamorous. It has no immediate impact on our daily lives, and its rise and fall does not decide elections.

Yet the statistics on labor force participation—“LFP” for convenience— are as informative in their own way as the statistics on unemployment. In the long run, they may be more important. The unemployment rate measures current economic conditions. Participation in the labor force measures a fundamental economic stance: an active intention of working, given the opportunity.

The Great Society reforms were not framed in terms of their effect on LFP, but in reality this was at the center of the planners’ concerns. What was commonly called the “unemployment” problem among the disadvantaged was largely a problem of LFP. The hardcore unemployed were not people who were being rebuffed by job interviewers, but people who had given up hope or ambition of becoming part of the labor force. For them, the intended effect of the manpower programs was to be not merely a job, but stable, long-term membership in the labor force.

As in the case of unemployment, my analyses of LFP are based on males. The role of women in the labor market changed drastically during the three decades under consideration, especially during the 1972–80 period (see the appendix, table 10, for data on women in the labor force). Interpretations of the relationship between LFP and social welfare policy are confounded by this separate revolution. But society’s norm for men remained essentially unchanged. In 1950, able-bodied adult men were expected to hold or seek a full-time job, and the same was true in 1980.

Unlike unemployment, LFP historically has been predictable, changing slowly and in accordance with identifiable rules. Therefore the Bureau of Labor Statistics had in the 1950s been able to project LFP into the future with considerable accuracy, and starting in 1957 such projections became part of the basic LFP statistics reported annually in the Statistical Abstract of the United States. In the 1967 volume, the Abstract for the first time broke down these projections by race, showing anticipated labor force participation to 1980 based on the experience from 1947 to 1964. The trend during those years plus the coming, known demographic shifts in the labor force of the 1970s led to projections of a modest increase in LFP for both black and white males.8 What actually happened was quite different.

In 1954, 85 percent of black males 16 years and older were participating in the labor force, a rate essentially equal to that of white males; only four-tenths of a percentage point separated the two populations. Nor was this a new phenomenon. Black males had been participating in the labor force at rates as high as or higher than white males back to the turn of the twentieth century.9

This equivalence—one of the very few social or economic measures on which black males equaled whites in the 1950s—continued throughout the decade and into the early 1960s. Among members of both groups, LFP began to decline slowly in the mid-1950s, but the difference in rates was extremely small—as late as 1965, barely more than a single percentage point.

Beginning in 1966, black male LFP started to fall substantially faster than white LFP. By 1972, a gap of 5.9 percentage points had opened up between black males and white males. By 1976, the year the slide finally halted, the gap was 7.7 percentage points. To put it another way: from 1954 to 1965, the black reduction in LFP was 17 percent larger than for whites. From 1965 to 1976, it was 271 percent larger.

In the metrics of labor force statistics, a divergence of this size is huge. The change that occurred was not a minor statistical departure from the trendline, but an unanticipated and unprecedented change. America had encountered large-scale entry into the labor market before, most recently by women, and had legislated withdrawal from the labor market—of children, in the early part of the century. But we had never witnessed large-scale voluntary withdrawal from (or failure to enlist in) the labor market by able-bodied males.

That the decline was most rapid during the exceedingly tight labor market of the last half of the 1960s made the phenomenon especially striking. A contemporary (1967) analysis of LFP published in The American Economic Review used data from 1961 to 1965 to reach the confident conclusion that, if unemployment dropped (as in fact was happening), we could expect major reductions in urban poverty among blacks as a tight labor market drew wives into the labor force. It was assumed that black male LFP would behave as it had in the past.10 It was a technically exact extrapolation from recent experience, but it was contradicted by events even as the author was waiting for his manuscript to be published.

Labor Force Participation Among Young Males by Race, 1954–1980

Data and Source Information: Appendix table 8.

Let us take a closer look at who was causing the divergence in black and white male LFP.

As in the case of unemployment, age is at the center of the explanation: As before, the young account for most of the divergence with whites. We begin with the three youngest age groups, the “job entrants,” aged 16–17, 18–19, and 20–24, as shown in figure 5.4.

It is the unemployment story replayed. The younger the age group, the greater the decline in black LFP, the greater the divergence with whites, and the sooner it began. The parallelism with the unemployment age trends is so complete that it is important to note that the two measures are not confounded. The unemployment rate is based only on those who are in the labor force. The people who were causing the drop in LFP were not affecting the calculation of unemployment.

On the face of things, it would appear that large numbers of young black males stopped engaging in the fundamental process of seeking and holding jobs—at least, visible jobs in the above-ground economy. There are at least two explanations, however, which would render the LFP statistic misleading: (1) that fewer young blacks participated in the labor force because they were going to school instead—a positive development; (2) that fewer young blacks participated in the labor force because the high unemployment rates made “discouraged workers” of them—why bother to look for a job if none are available?11 Both require examination.

“THEY WERE GOING TO SCHOOL INSTEAD”

First, let us consider the merits of the education hypothesis. From 1965 to 1970, LFP among black males dropped by the following amounts (expressed as the percentage of the population in 1970 minus the percentage of the population in 1965).

| Age Group | Reduction in LFP |

| 16–17 | –4.5 |

| 18–19 | –4.9 |

| 20–24 | –6.3 |

At the same time, school enrollment increased by these amounts, using the same metric:12

| Age Group | Increase in School Enrollment |

| 16–17 | +1.8 |

| 18–19 | +.5 |

| 20–24 | –1–5.2 |

Even if we make the extreme assumption that all of the increased enrollment represented students who would have been in the labor force if they had not gone to school and that none of the people who were added to the school population also participated in the labor force, the increases in school enrollment would not cover the decreases in LFP. In fact, of course, those assumptions are incorrect, further shrinking the proportion of the reduction in LFP that could be explained by school enrollment. More than a third of students in those age groups participate in the labor force, and many who are not students do not participate.13 The white experience indicates that school enrollment may be altogether irrelevant in explaining the change in black LFP. White male LFP in two of the three job-entry age groups increased along with school enrollment:

| Change in | ||

| Age Group | LFP | School Enrollment |

| 16–17 | +4.3 | +2.8 |

| 18–19 | +1.6 | +1.6 |

| 20–24 | –2.0 | +2.3 |

The “school enrollment” hypothesis explains at best a small fraction of the reduction in black LFP; judging from the white experience, we may not be justified in using it to explain any of the reduction.

THEY GAVE UP LOOKING FOR JOBS THAT WEREN’T THERE”

The “discouraged worker” hypothesis is probably an explanation for part of the reduction in certain age groups in certain years. For rural populations, the disappearance of agricultural jobs meant picking up roots, establishing a new home and a new style of life, and accommodating to the demands of a strange job market. The adjustment was a difficult one, and the reductions in black teenage LFP in the last half of the 1950s can plausibly be read, at least in part, as a reflection of this. Economic bad times also produce discouragement. During recessions—1957–58, for example, or 1974–75—the reductions in LFP among the most vulnerable workers (young black males) are easily seen as discouragement.

But it is not possible to use discouragement as an explanation for the long-term trend. Why should young black males have become “discouraged workers” in greater numbers in the 1960s than they did during the less prosperous 1950s and 1970s? Even within the decade of the 1960s, the “discouraged worker” hypothesis fails. In 1960, young black males (ages 16–24) had an LFP rate of 74.0 percent, 2.7 percentage points higher than the LFP rate of white males of the same age range. By 1970, the gap was 3.6 percentage points in the other direction (whites higher than blacks). Here is how the gap developed in each half of that key decade:

| Years | Ground Lost in LFP Percentage by Young Black Males in Comparison with Young White Males (Aged 16–24) | Mean Male Unemployment |

| 1960–65 | 2.3 percentage points | 5.1 % |

| 1965–70 | 6.1 percentage points | 3.4 % |

In the half of the decade when the economy was not only strong but operating at full capacity, the difference between young whites and blacks grew fastest—more than two and a half times as fast as during the first half of the decade, with its considerably higher overall unemployment rate.

LFP among older age groups of black males during the same period is given in the appendix. In general, white and black LFP rates changed in tandem. Divergences were perceptible in each of the age groups: The participation rates of blacks and whites in the 1950s were uniformly closer than in 1980. In each case, the major portion of the divergence occurred during the 1970s. But among older workers the absolute changes were quite small.

A Question of Generations

The age breakdowns show an oddly regular pattern, as if contagion were spreading slowly upward from young to old. What was really happening, of course, is that the same people were getting older. The 16-year-olds of 1963, when the black-white gap widened, were 19 in 1966—when blacks of that age fell noticeably behind whites—and 24 in 1971, when the crossed over point was reached for the 20–24 year-old age group. We are watching a generational phenomenon. For whatever reasons, black males born in the early 1950s and thereafter had a different posture toward the labor market from their fathers and older brothers.

What was different about being born after 1950? The difference lay in the environments in which different groups came of age in the labor market. Those born in 1950 turned 18 in 1968, when the rules governing the labor market had been changed radically. The intended changes were all for the better, surely—more training programs for poor and minority youth, better regulations on equal opportunity and widespread social support for their enforcement, higher minimum wages, a red-hot economy. Yet, the 1950 black youngsters behaved conspicuously differently from their older brothers and from their white counterparts. And, to put it another way, a population of disproportionately poor youngsters behaved conspicuously differently from the way poor people in previous generations had behaved.

Escaping Stereotypes

The data I have just described are too often sidestepped by appealing to either of two stereotypes. One stereotype is the welfare loafer, living contentedly off the dole and making no effort to work. The other is the steadfast job-seeker, fruitlessly going from door to door looking for any kind of work. Neither fits very many of the people who account for the changes in the unemployment and LFP statistics. More often, these people share some of the characteristics of both stereotypes, at different times. Martin Feldstein describes the situation in a year typical of the seventies, 1979:

In 1979, more than half of those who became unemployed were no longer unemployed at the end of four weeks. More than half of the unemployed were less than 25 years old and half of these were teenagers, many of whom were looking for part-time jobs while still attending schools. More than half of those who were officially classified as unemployed did not become unemployed by losing their previous job, but were youngsters looking for their first job or those who were returning to the labor force after a period in which they were neither working nor looking for work. . . . In short, the unemployed typically are young, have generally not lost their previous job, and have very short periods of unemployment. . . . It is a picture that stands in sharp contrast to the image of a stagnant pool of job losers who must remain out of work until there is a general increase in the demand for goods and services.14

The problem with this new form of unemployment was not that young black males—or young poor males—stopped working altogether, but that they moved in and out of the labor force at precisely that point in their lives when it was most important that they acquire skills, work habits, and a work record. By behaving so differently from previous generations, many also forfeited their futures as economically independent adults.

Summary of the Federal Effort

THE JOHNSON job-training programs started from near zero. From the onset of the Second World War until Kennedy came to office, the federal government effectively stayed out of the jobs business. When it came to finding work, the poor and the unemployed mostly fended for themselves; private agencies and scattered state-level programs were the only sources of help.

In the 1960s, John Kennedy reopened federal involvement in employment with the Area Redevelopment Act (ARA) in 1961 and the Manpower Development and Training Act (MDTA), passed in 1962. ARA was restricted to narrowly defined “depressed areas,” and MDTA was to retrain displaced employees, not help the chronically unemployed. It remained for the first antipoverty bill to introduce broadly based efforts to help the disadvantaged in the employment market.

From 1964 to 1970, the programs focused on skills training. Job Corps was perhaps best-known, but it was dwarfed in size by other programs which proliferated throughout the rest of the decade— Operation Mainstream, New Careers, and Job Opportunities in the Business Sector, to name a few. Some programs did not offer skills training per se but were intended to serve a general antidelinquency and socialization function for youths. The Neighborhood Youth Corps was the largest such effort—an “aging vat,” as Sar Levitan has put it, in which youngsters at a critical transition point could be kept from dropping out. By 1969, at least seventeen programs were generating more than 10,000 specific manpower “projects” of varying size and scope.

In 1971, the emphasis changed. The Emergency Employment Act moved away from skills-training and toward counter-cyclical employment. Training programs continued, but alongside new and expanded programs whose main purpose was the simpler one of providing work for the disadvantaged, with emphasis on the young. The multiple agencies and departments involved in the overall jobs/training effort were brought under a single administrative umbrella through the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA) of 1973. At its height, CETA had an annual budget of $10.6 billion.

For an overview of the training programs, see Henry M. Levin, “A Decade of Policy Developments in Improving Education and Training for Low-Income Populations,” in Robert H. Haveman, ed., A Decade of Federal Antipoverty Programs: Achievements, Failures, and Lessons (New York: Academic Press, 1977), pp. 123–188.