10

The View from 1966

THE PROPOSITION underlying the last six chapters is that things not only got worse for the poor and disadvantaged beginning (in most cases) in the last half of the 1960s, they got much worse than they “should have gotten” under the economic and social conditions that prevailed in the society at large. This is of course a hazardous assertion. It is not susceptible to proof, and, ex post facto, we can concoct some sort of benign explanation for almost any catastrophe—benign in that it tells us we were helpless to prevent it.

But the explanations must indeed be after the fact. For no one prior to the reform period could have predicted the trendlines in the years to follow even if one had been given prescient knowledge of the state of the economy and other salient factors. To illustrate, a little role-playing may help.

Let us set our role-play in December 1959. The civil rights movement is gaining momentum, but the economy is still suffering the after-effects of a major recession, the Congress is divided, and the president is passive. Let us say that I am a policy analyst appearing at a colloquium on Negro progress during the 1950s. (No one will ask me about the progress of the poor during the 1950s; the poor had yet to be rediscovered.) In my comments I acknowledge a generally upward trend in the progress of Negroes, but I express my concern about the wide gap still separating whites and Negroes on almost every dimension of economic and social well-being. Then the moderator puts a hypothetical question to me:

Suppose that in the next decade we pass sweeping civil rights legislation forbidding all discrimination on the basis of race—in hiring practices, public accommodations, and voting. Suppose that we further require businesses and schools to take special measures to recruit Negroes. Suppose further that the civil rights movement leads to an upsurge of racial pride and assertiveness among Negroes. Suppose further that we pass legislation that will pay for college for just about everybody who qualifies and provides free job training to just about anyone who wants it. Suppose, finally, that during this same period we enjoy continuous economic growth. What then would you predict for Negro progress in closing these gaps you speak of?

From my vantage point of 1959,1 reject the suppositions as preposterously optimistic. But if they all did come true? Of course, the gaps would narrow. It would be inconceivable to predict anything else.

Then, let us imagine, the panelist sitting beside me says: ‘’No, what will happen is that the younger generation of Negroes will leave the labor force, form huge numbers of single-parent families, and experience soaring rates of crime and illegitimacy and unemployment.”

My reaction is that I am listening to nonsense. Even if my prescient colleague could foresee the riots and the Vietnam War, it would be extremely difficult to explain to me or any other observer in 1959 how such events could possibly override the progress that would be sure to accompany the hypothetical changes. I respond that something else, of extraordinary influence, would have to be added to the scenario to produce the outcomes predicted by my colleague.

The purpose of the role-playing is to point up that our ex post facto explanations cannot easily pass off what happened in the 1960s and 1970s as “part of the times,” Any explanations must take into account the many respects in which the trends went against the grain of the times.

Now, let us be more specific about the numbers. I have referred periodically throughout the last six chapters to the “steepening trendline” or the “unexpected change” in the late 1960s. To convey a sense of how the disparate indicators and trends hang together, let us again do some pretending.

This time, let us imagine that it is June 1966. I am a policy analyst in the Johnson White House. My task is to help design the next phase of the War on Poverty. To this end I have been asked to project the progress of the disadvantaged some years out—to, say, 1980. I am told to use as my test population for this purpose the most disadvantaged group of all, black Americans. The analytic question is this: Based on what we know now— through 1965—what can we expect the future to hold? The purpose of the analysis is to separate the problems that will more or less solve themselves in the natural course of events from those that will continue to plague the disadvantaged unless special remedial steps are taken.

As analysts often do in such cases, I begin by defining an “optimistic” scenario and a “pessimistic” scenario. If I project on this basis for each of the scenarios independently, an envelope is formed within which the true future is likely to fall.

As the basis for the optimistic scenario, I am inclined to take the years since John Kennedy came to office to the present—that is, 1961 to 1965. The year 1961 is a natural breakpoint, dividing the Eisenhower from the post-Eisenhower period. Also, I reason, 1961–65 has been a period of steady economic growth, reductions in poverty, stabilization of black unemployment among the young, and reductions of black unemployment among older workers. As the basis for the pessimistic scenario, I take the years 1954–61—the post-Korea Eisenhower years. I choose 1954 in part out of necessity—it is the first year for which detailed annual information about the black population is available—but it also has a symbolic appropriateness as well, marking the Brown v. Board of Education decision, the first of the great civil rights victories in the courts.

I call the scenarios “optimistic” and “pessimistic,” but in reality I consider both of them to be biased toward the pessimistic side. Even the optimistic one says, “This is what 1980 will look like if the rate of progress is no better and no worse than it was from 1961 to 1965,” and, from my perspective in 1966, that is not an ambitious objective. I do not consider that the period 1961–65 has been an exceptionally good one for blacks. Black voices have been raised, but black economic and social progress has been slow. The civil rights movement has not yet brought about the necessary rates of improvement. It has finally produced the instruments— legislation, court rulings, regulations—that are indispensable to adequate improvement, but the effects of these steps have barely begun to be felt. The economic and social action programs of the Great Society are just getting off the ground. It must be presumed that the implementation of these laws and programs will accelerate the bootstrap progress that blacks have made to date. And there is no telling what additional social legislation will be passed in future, especially given Johnson’s continuing legislative hegemony. On all these counts, a straight-line projection of black progress in either 1954–61 or 1961–65 should tend to underestimate the real rate of improvement from 1965 to 1980.1

As I proceed with my analysis, I choose indicators of two types. First I choose five indicators to assess the progress of the poorest blacks who have survived on the fringes of American society. Two of the indicators represent the problems that have been much worse for these blacks than for other groups:

- black victims of homicide, and

- black illegitimate births.

I want to see both of them go down. The other three of the indicators represent paths for getting off the bottom and up the socioeconomic ladder:

- labor force participation of black males aged 20-24 (it should go up);

- jobs for young black males (I use the unemployment ratio of black males aged 20–24 to white males of the same age, and hope to see it diminish); and

- two-parent families (which, aside from their noneconomic merits, are a mechanism whereby poor people accumulate resources, and are hoped to increase).

The second set of indicators that I choose for my analysis for the White House is primarily for assessing the progress of blacks who are already within the economic mainstream—seldom rich, but regularly employed, making a decent living. They have been held down by discrimination. How will they fare by 1980? I select four measures:

- income ratio of full-time, year-round black workers to comparable white workers (it should rise);

- unemployment ratio of black males aged 45–54 (an age group representing the mature male, with a family to support, who is almost always in the labor force unless physically incapacitated) to comparable white workers (it should come down);

- percentage of black workers employed in white-collar jobs (it should go up); and

- percentage of black persons of college and graduate school age (20–24) enrolled in school (it should go up).

Upon calculating my upper and lower bounds for each indicator, I soon discover that my “optimistic” and “pessimistic” scenarios do not altogether square with what has happened as of 1966. On six out of my nine indicators (unemployment ratio among young males, two-parent families, illegitimate births, arrests for violent crimes, income ratio of full-time workers, and persons of college age enrolled in school), a linear projection from the period 1954–61 yields a more positive projection for 1980 than the one based on 1961–65.

I attribute this to extremely low baselines for some of the indicators (see note 1). For the others, it seems plausible (ex post facto thinking at work) that the ferment of change in the black community might have short-term dislocating effects, causing such things as a higher illegitimacy rate and lower proportion of two-parent families. These are presumably only temporary phenomena. But I do re-label my trendlines, putting the “optimistic” label on whichever line is more positive, regardless of whether it came from the 1954–61 period or the 1961–65 period. I prepare my graphs, give them to my supervisor, and they show up in someone’s briefing book a few weeks later. By 1980, I have forgotten that I ever made such foolish guesses.

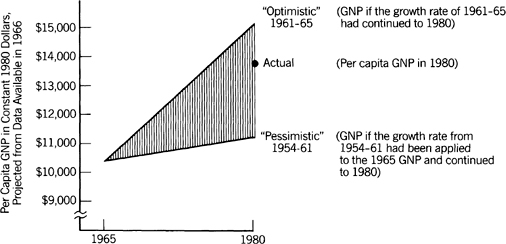

Had anyone in 1966 actually been given the task of projecting these indicators to 1980 (analogous exercises were actually conducted2), the projections would have been of the same order as the ones in the graphs we are about to examine—not because people were naive then, not because the techniques are inherently inappropriate, but because, in the absence of some strange and powerful intervening factor, they are roughly the ranges within which reasonable people would have expected these indicators to fall.3 With that in mind, let us examine the mocked-up 1966 projections, adding to them the true value of each indicator as of 1980. I begin with a sample of the general format, a projection of real per capita GNP (see fig. 10.1):

A Projection of Per Capita GNP from 1965 to 1980

The other graphs follow this model, with abbreviated notation. Before leaving the sample, take note that real per capita GNP was just about where it was supposed to be by 1980, a bit toward the optimistic side of the envelope.

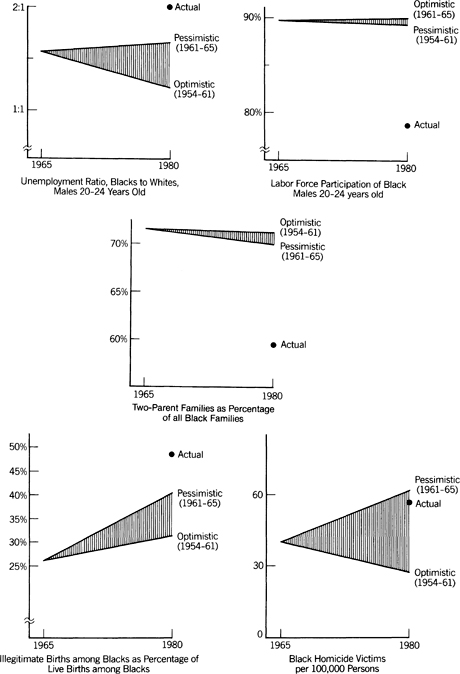

Figure 10.2 shows the indicators pertaining especially to the black poor.

The View from 1966, Part I: Black Prospects on Indicators Especially Pertinent to the Poor

Data and Source Information: Appendix tables 7 (unemployment), 8 (labor force participation); 18 (homicides), and 24 (illegitimate births and two-parent families).

The graphs convey in summary form, and perhaps more vividly than any of the individual discussions could, one of the themes of the last six chapters: how far outside the “normal course of events” the black poor have moved. Nor are these indicators unrepresentative. One may choose virtually any measure concerning the black poor for which data are available and come up with the same finding.4 In 1966, we were very far off the mark when we tried to imagine what “pessimistic” might mean when it came to projecting the future of the most disadvantaged of black Americans.

Figure 10.3 shows the other theme of these chapters—that some have done quite well, even extraordinarily well. Consider the indicators of progress especially pertinent to working- or middle-class blacks:

The View from 1966, Part II: Black Prospects on Indicators Especially Pertinent to the Not-Poor.

Data and Source Information: Appendix tables 7 (unemployment), 8 (labor force participation), 11 (white collar jobs), and 12 (school enrollment).

The optimistic projection from 1966 was that white-collar employment of black workers would increase by 65 percent. The real increase turned out to be 101 percent. The optimistic projection from 1966 was that the proportion of young black adults (20–24 years old) in school would increase by 41 percent. The real increase was 95 percent. The income ratio of black full-time workers to white full-time workers reached 75 percent in raw form, slightly above the top of the projection envelope. Only the unemployment ratio of middle-aged workers fell short of the optimistic projection—and it was at least within the projected range. In short, for middle-aged blacks, middle-class blacks, and blacks who obtained middle-class credentials, the years 1965–80 were generally as good as or better than either the 1954–61 or 1961–65 periods would have led us to expect.

The profiles of the two populations are at odds with each other—one much worse than we would have anticipated, the other doing quite well. Such was the burden of the more detailed analyses of these issues in part two. Such is the puzzle of causation that, finally, we begin to examine.