5

Back-country

Sleeping on the ground will never be quite as comfortable as sleeping in a bed indoors—but if you can learn to love it, camping out has many side benefits: great views of the sunset and sunrise, campfire conversations, an unobstructed look at the stars in the middle of the night, and the unique satisfaction of sipping from a mug of hot coffee the morning after a chilly night spent in a sleeping bag. Knowing a few basic skills and tips can make a night outside more comfortable so you don’t feel as though you’re roughing it.

This chapter will give you a sense of where to camp, how to find a good campsite, the gear you need, what to eat and how to cook it, how to light a campfire (and more important, how to put it out), how to pitch a tent, and everything you need to plan your first camping or backpacking trip. Follow these tips and you’ll find that sleeping in a tent is like staying in a million-star hotel.

Why should I try backpacking?

Backpacking can definitely seem like a lot of work. After all, you’re carrying everything you need for a few days and nights on your back, and that can be pretty heavy to haul around steep trails for miles and miles. And, of course, there are no bathrooms or electricity in the backcountry. But if you’re the type of person who believes all good things come at a price, it’s worth it. What you trade in comfort you get back in solitude and scenery: statistics show the majority of national park visitors never get more than a mile from their cars, and if you’re willing to put in a little sweat equity and carry your tent, sleeping bag, and food into the backcountry, you’ll be rewarded with an escape from people—and likely a great view of an alpine lake or mountains, or a secluded forest campsite. If you’re interested in hiking and you’re interested in camping, backpacking combines both: simply put, you’re just hiking to your campsite.

Where can I go camping?

There are two basic designations for camping: campgrounds and dispersed camping (see here).

Developed campgrounds include privately owned campgrounds and RV parks, national park campgrounds, state park campgrounds, county park campgrounds, municipal campgrounds, US Forest Service campgrounds, and Bureau of Land Management campgrounds. Almost all developed campgrounds charge a fee per night of usage, from five dollars to forty dollars. Generally, developed campgrounds will have—at minimum—established campsites, fire rings, picnic tables, water spigots, and bathrooms or vault toilets. Some developed campgrounds have amenities like bathrooms with running water and electricity (and sometimes showers), trash receptacles, grills, campground staff, and even laundry.

Dispersed camping is a term for primitive camping that’s allowed anywhere on public land managed by the US Forest Service or the Bureau of Land Management. Dispersed camping covers both car camping and backpacking or backcountry camping—as long as you can get your stuff there, you can sleep there. Dispersed camping is entirely without the amenities and infrastructure of developed campgrounds—for example, you might find a flat spot with a fire ring just off the side of a dirt road on Forest Service land, or you might backpack two or three miles from a trailhead on Bureau of Land Management land and pitch your tent in a flat spot.

When using a dispersed camping site (or creating your own), you are expected to take all trash with you and bury human waste.

Can I camp next to a river or lake?

You can camp near a river or lake, but it’s bad form to camp right next to it (even if you really, really, really want to take a photo of your tent next to a lake for Instagram). To protect the area for future users (remember, someone protected it for you), camp at least 200 feet from a water source. You don’t have to be exact, just respectful: walk about seventy-five big steps from the edge of a lake (that’s roughly 200 feet) and find a spot near there, or better yet, find an existing campsite and use that.

How do I find a campsite in the backcountry?

When you’re backpacking, finding a place to sleep isn’t quite as simple as pulling off the freeway at the next motel or Googling “hotel” on your smartphone—but it’s pretty easy. You’re going to need water to cook breakfast and dinner, so the most logical place to camp is near water—luckily for you, most other people who have gone backpacking before you are just like you, so they’ve probably established campsites near water sources. When planning your trip, look at the map and figure out a few possible goals for your first night, based on how far you can reasonably hike (whether that’s 2 miles or 10 miles). Lakes and ponds are the easiest places to find campsites, as there’s usually flat land somewhere nearby. Creeks and rivers are also good water sources but sometimes don’t reliably have flat spots nearby—the blue line signifying a creek on your map can be pinched in a steep gully, with nowhere nearby to pitch a tent. But if the contour lines on your topographic map are far apart near a creek, there’s a good chance there’s some flat land.

Hike to your water source—again, a lake or pond is your safest bet—and when you arrive, explore the perimeter of the water for established campsites—they should be about 200 feet away from the water’s edge and should have one or more flat spots free of vegetation where tents have been pitched in the past (and where you can pitch your tent). It’s best to use established campsites for a couple reasons: it minimizes damage to the area, and it’s easy—you don’t have to stamp down grass and pull out rocks to clear a spot for your tent. Additionally, if you’re lucky, someone has pulled a downed tree over to the campsite and made it into a good bench for you to sit on while you’re emptying your pack and/or cooking dinner.

In a pinch, of course, you can camp somewhere not near a water source, but remember, the only water you’ll have to make dinner and breakfast (and coffee!) is what you’ve got in your backpack, so plan wisely.

How can I tell if a spot is flat enough to sleep on?

You’ll never find a spot in the backcountry that’s truly flat, not in the way you can measure with a carpenter’s level when you’re working on your house. If you think a spot looks flat, it’s probably pretty close. One trick that will help: Before you set up your tent only to find out it’s slanted downhill at an unacceptable angle, lie down in the exact space where you’re going to put your tent. If it feels too tilted, find another spot. If you think it might be okay but you’re not sure, go ahead and set up your tent but don’t stake it down. Set it in the exact spot, and if it looks tilted too much, try turning it or moving it to the right or left a little bit—the visual will help you decide. If you’re still not sure, unzip the door and get in the tent and lie down—if you’re sliding (even a little bit) in one direction or another, it will probably be a pretty miserable spot. Look for a better spot nearby, and if you can carry your tent over to the new spot without breaking it down, go for it.

How close to someone else’s campsite can I set up my tent?

It’s safe to assume—unless the person indicates otherwise—that everyone you see in the backcountry has gone there to get away from people. A person may be friendly and chatty when he sees you on the trail, but unless he specifically invites you to camp right next to him, it’s probably better to keep your distance. If at all possible, set up your tent out of sight from other tents, and if that’s not possible, give the other tents 150 feet or so of space. If you’re in doubt, it never hurts to ask before you put up your tent, with a simple “Would it be okay with you if I set up camp over here?” Most people aren’t territorial about campsites or interested in hogging the view of an alpine lake—but it’s courteous to ask first.

Is it okay to listen to music at my campsite?

It’s okay to listen to music at your campsite, with a couple of caveats: be aware of how close the next campsite is, and whether there are people camping there who may or may not like to listen to your EDM all night—or really at all. Most people head to the backcountry to escape noise, and although it might be hard to imagine, plenty of people have different musical tastes than you do and might find your choice of dinner music undesirable. But if you don’t have close neighbors at your campsite, there’s no reason you can’t listen to some music. Just make sure it’s not reaching everyone else at the campground. After you turn on the music, take a walk away from your campsite and see if you can hear the tunes from other spots in the campground, especially near other people’s campsites. If not, you’re probably okay. If you can hear it, the courteous move is to turn the music down (or off). Just remember not to mess with the volume after you’ve had a beer or three, because obviously your judgment will be altered somewhat. Whatever you do, try not to be that person that everyone in the campground hates.

How do I light a campfire?

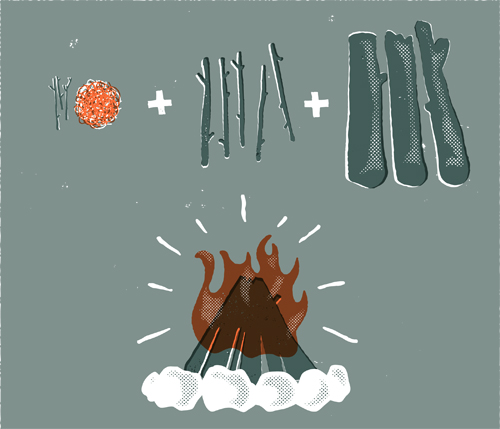

First, build a fire ring or find an existing fire ring near your campsite to keep the fire from getting out of control. A dozen or so fist-sized rocks should be enough for a fire for two people, and double that number for three or four people. The diameter of your fire ring shouldn’t be bigger than about 2 feet—you are building it to stay warm while camping for an evening, not roasting a whole pig over it. There are three components to a campfire.

1. Tinder: Has to be dry, has to catch fire easily, and will burn quickly (so grab a lot of it). Dry green cottony fungi works, as do dry leaves, dead grass, small shards of leftover firewood (often easily found surrounding campfire rings at campgrounds), dry bark found around downed trees, and wood shavings (which you can whittle and/or splinter off your fuel wood).

2. Kindling: Imagine your fire having to work its way up to big chunks of wood. It has to burn the small stuff first (the tinder), then medium-sized stuff, which is the kindling: pinky-diameter or smaller pieces of wood. Again, your kindling has to be dry or it won’t burn. So don’t go snapping small branches off live trees. Look for downed trees or broken-off branches, and gather a bunch—two large fistfuls or more.

3. Fuel wood: Fuel wood is wood that will burn hot and long once you’ve gotten your actual fire going. When gathering wood, look for pieces the diameter of your wrist or bigger. Don’t go too big—you’re not looking for a Yule log. Grab a few pieces that are wrist sized and some bigger than that. Look for dry wood.

Now, imagine a fire having to climb up stairs—the first step is the tinder, the second one is the kindling, and the third step is your fuel wood. Place the tinder and kindling in the shape of a teepee: tinder on the bottom and the kindling on top of that in a small teepee—twigs and sticks balanced against each other in a cone shape, with enough space in between the twigs so that air can move through the teepee, and enough space on a few sides that you can reach the tinder with a lighter or lit match. Once you’ve got a good teepee of tinder and kindling, light the tinder in three or four spots. Watch closely to see if the fire is spreading from the tinder to the kindling—gently blow on it from a few directions to help it get oxygen. When blowing on the fire, don’t be afraid to get close—down on all fours, face close to the ground. Once you’re convinced the fire is taking to the kindling, start to put on your fuel wood—again, build a teepee, and start with your smallest-diameter fuel wood. As the small fuel wood starts to burn, go ahead and add the larger-diameter fuel wood.

At some point, your teepee will probably collapse on itself—don’t sweat it, just make sure that when you add wood you arrange it so the wood can get some oxygen on the bottom as it burns. Lay pieces of wood at angles on each other, and keep a stick handy to adjust wood in the fire as it burns to keep oxygen flowing through it.

Should I carry matches or a lighter?

It’s really a matter of personal preference, but the best thing to take to light a fire is actually two things: matches and a lighter, or two lighters. Unless you’ve got a 100 percent reliable lighter, either matches or a lighter can fail (or just be impossible to light in certain windy or rainy conditions), and then you’re without a fire for the night—unless you’ve mastered making a fire without ignition. With both matches and lighters, make sure they’re in a waterproof container, because even getting them damp can make them impossible to light. A prescription pill container can work as a carrying case, or a sturdy ziplock bag (just make sure it doesn’t get holes poked in it as it starts to rack up the miles riding inside your backpack). Outdoor gear stores usually sell several types of waterproof or “light anywhere” matches, which can be nice but are often unnecessary—a book of matches from a restaurant or bar is usually fine as long as you keep it dry.

Can I make a fire on a rainy day?

A few sprinkles or even a major downpour doesn’t have to put the kibosh on having a campfire. If it’s just sprinkling intermittently, your campfire might not get wet enough to go out, so light it and see what happens. If it’s going to downpour, you have two issues to deal with: finding dry wood and keeping your fire from getting soaked. If there’s a lot of rain in the forecast for your camping weekend, consider bringing a tarp and lots of cord to string up a shelter to keep your fire from the rain. Remember, heat rises, so when you’re stringing up a tarp above where your fire will be, give the fire some respect and distance so it doesn’t burn through the middle of your tarp. Anchor the tarp to four trees, making sure it’s taut so rainwater won’t gather in the middle of the tarp and weigh it down, and slightly angled so the rain will drip off one edge of the tarp. If the tarp is roughly 7 or 8 feet above the ground, it should be high enough that it won’t be in danger of getting burned by the fire, as long as you’re not building a ridiculously large fire. If you’re buying a tarp specifically for the purpose of sheltering a campfire, take into account the fact that you and your friends will probably want to stand or sit around the fire, and ideally you’ll be out of the rain too—so get a tarp big enough to cover both the fire and a circle of chairs around it (15 by 15 feet should be big enough for a group of up to six people). And don’t forget the dry wood—keep it in, or underneath, your car, or if you have enough space under your tarp keep a stash there.

How big should my campfire be?

It’s fun to make big fires—just admit it. But a big fire is unnecessary unless you’re trying to keep twenty-five people warm, which you’re probably not. On a camping trip, make your fire size proportional to the number of people in your group. If everyone’s huddling around the fire, it’s a little too small. If you find everyone keeps scooting his or her chair back away from the fire because of the heat, it’s too big. And remember, unless you brought a trunk full of firewood, the fire lasts only as long as the supply of wood lasts. So keep your campfire as small as comfortably possible, and you’ll be able to sit around your caveman TV much later into the evening.

Should I burn my garbage?

Although throwing your garbage in a campfire to get rid of it might seem like a good idea (then you won’t have to carry it out, right?), you’ll probably find that most of your backpacking garbage doesn’t burn well and you won’t be saving that much weight either. Plastic food bags and energy bar wrappers don’t weigh that much after they’ve been emptied, so it’s best to just bring them out with you. Don’t attempt to burn aluminum foil in a campfire either—it never completely burns, and it leaves pieces of aluminum in the ashes, which eventually blow all over the forest and spread trash everywhere. A 1-gallon ziplock bag should fit a week’s worth of trash on a backcountry trip.

Devote a little energy to minimizing trash when you’re packing your food before your trip—get rid of cardboard boxes and put things in plastic bags whenever possible. That box of macaroni and cheese will take up less space in your pack if you transfer it into a plastic bag before the trip, and it will be in less danger of bursting open inside your pack and spilling everywhere.

How do I put out my campfire?

Smokey Bear will tell you to make sure you put your campfire out every time, for good reason: some of the most catastrophic forest fires in the past few decades have been human caused (some intentional, some unintentional). To make sure your fire is completely out, break up any still-hot coals into smaller pieces (use a stick so you don’t burn your hands), spread them around the fire ring, and then pour water on the coals to make sure they’re completely out. If you’re conserving water, you can pee on the coals, but be warned: urine on hot campfire coals produces a pretty bad smell. Another good policy: Be careful not to put a large piece of firewood on the fire as things at camp are winding down for the night. You don’t want to be the last person up waiting by yourself for that thing to burn down, and it’s an amateur move to leave a big piece of unburned wood in a campfire ring for the next party to find.

Is it okay to leave apple cores and banana peels on the trail?

Fruit is biodegradable, so it’s okay to leave it on the trail, right? Yes, it’s biodegradable, but no, it’s not okay to leave it out where you’re hiking. Orange peels and apple cores take six months to decompose in the outdoors, and banana peels take up to two years—and they don’t exactly blend in with the natural environment when you toss them off to the side of the trail. So keep a small trash bag in your pack and carry everything out with you.

The Eight Backpacking Trips of a Lifetime

1. Grand Canyon Rim-to-Rim, Arizona, USA: A three-day backpacking trip down to the bottom of the Grand Canyon and up the other side

2. John Muir Trail, California, USA: A classic twenty-one-day trek across the Sierra Nevada, including Yosemite

3. Inca Trail, Peru: A four- to five-day trek to the fifteenth-century Inca dwelling of Machu Picchu

4. Routeburn Track, New Zealand: The premier mountain hut–to–mountain hut hiking route in the mountains of New Zealand’s south island

5. Hiker’s Haute Route, France/Switzerland: The famous hut-to-hut hiking route across the Alps connecting the famous mountain towns of Chamonix and Zermatt

6. Alta Via 1: The weeklong hut-to-hut trek across the Italian Dolomites

7. Everest Base Camp: A ten- to fourteen-day trek through the giant mountains of the Himalayas to the base camp for Everest climbers, elevation 17,600 feet

8. Torres del Paine trek, Chile: A five-day trek through the famous granite spires of Patagonia

What do I need to go car camping?

Car camping is the most beginner-friendly type of tent camping—you can pretty much take whatever you want, as long as it fits in the vehicle you’re driving to the campground. And you don’t need the highest-tech or most expensive gear to do it. Here are the basics.

• Stove: You can, of course, choose to cook over an open campfire, but it usually leaves your pots and pans coated in a layer of black soot, and a fire is tougher to keep at a consistent temperature, so stoves are easier and more reliable. Most department stores with a sports section sell camping stoves that work great. If you think you might like to try backpacking, buy a one-burner stove—it will work for car camping and also for backpacking (because there’s no way you’ll haul a big two-burner stove anywhere in a backpack). With the stove, you’ll also need fuel, so be sure to buy the corresponding fuel to whichever stove you buy (propane or isobutane, usually).

• Pots: If you don’t want to spend money on specific camping pots and pans (usually you’ll only use one or two pots, or a pot and a pan, when you go camping), just grab a pot or two from your kitchen and toss it in your car—as long as it isn’t a precious gift from your deceased grandmother and you can’t bear to think of getting it dirty or scratching it while camping. If you do want to buy pots, consider getting a set in which a smaller pot rests inside a bigger pot—these sets are great for packing and are also ideal if you decide later to try backpacking.

• Flatware: Again, your flatware from your kitchen at home will work just fine. Or you can buy a set of plastic/Lexan spoons and forks from an outdoor store for a couple dollars. Just don’t forget to bring some, or you’ll be eating your pasta with your fingers.

• Plates and/or bowls: The plates and bowls you have at home are probably breakable and not designed to handle a bumpy car ride or much abuse in the outdoors, so it’s best to buy some hard plastic, steel, or titanium bowls and/or plates made for camping. If you’re choosing between plates or bowls, bowls are usually more versatile for camp food (you can eat oatmeal out of a bowl but not off a plate, for example).

• Food: Generally, if you can cook it in a pot or pan, you can cook it while camping. You won’t have an oven, so things like lasagna and cookies are probably out. But everything else is fair game: hot dogs cooked over the fire, pasta dishes, soups, oatmeal, pancakes, and even tacos are great camping meals. If you’re nervous about what to cook, bring something simple that cooks in a single pot, like macaroni and cheese.

• Water/water container: Many campgrounds have running water, but it’s not that likely that the water pump will be right next to your campsite. It’s good to have a 3- to 7-gallon jug in your car that you can either bring filled with tap water from home or fill at the campground—you’ll be doing lots of cooking, washing dishes, and washing hands, and you’ll probably use more water than you think.

• Coffee-making apparatus: If you’re a regular coffee drinker, camping isn’t the time to try to go without it. Bring instant coffee or another way to make your morning coffee (see here).

• Firewood: If you want to have a campfire, it’s best to bring some firewood to the campground (if it's allowed). Some campgrounds will sell firewood, but don’t count on it. Pick up a bundle or two from a grocery store or gas station on your way. It’s also a good idea to bring a hatchet to split up thick chunks of wood.

• Camp chairs: You might get lucky and find a fire ring with perfect-sized logs surrounding it, but for long-term campfire sitting a good canvas camp chair is best.

• Tent: You don’t need to spend a thousand dollars on a tent, but if you buy a lower-end tent make sure it has a rain fly—inexpensive tents are often sold separately from their corresponding waterproof rain flies, and without the rain fly you might be in for a wet night.

• Sleeping bag: Again, you don’t need to spend a pile of money (see here), but the more you spend, the higher quality your bag will be, and usually the less likely you’ll be to freeze. Consider the low temperature for the nights you’ll be camping, and buy a sleeping bag rated to well below that (e.g., if the low is in the 40s, get a sleeping bag rated to 20°F or even 15°F).

• Sleeping pad: It’s tempting to buy a thick air mattress for camping, since they’re theoretically the most comfortable. But be warned: All that air underneath you will act like a refrigerator when it cools down in the night, and sleeping on 5 or 6 inches of cold air can be very uncomfortable. Thinner sleeping pads will be less comfy but warmer, so they’re better for sleeping overall. If you’re worried about a sleeping pad being too thin, bring a thin foam mat to place underneath it to double up the cushioning.

Should I bring a flashlight or a lantern?

When it comes to lighting your campsite, the most functional thing you can pack is not a flashlight or a lantern—it’s a headlamp, a light worn on a strap around your head. The light points where your head points, and you don’t have to hold it in your hand like a flashlight, so you can do things that require both hands, like carrying firewood, cleaning dishes, or cooking. Lanterns are nice to light up tables or cooking areas and they add ambience to campsites; although they used to require fuel and sometimes hard-to-replace parts, many lanterns nowadays are battery powered or rechargeable by USB or AC outlet. Flashlights are fine if you don’t want to spend the money on a headlamp, but once you convert to using a headlamp while camping, you may find yourself using it at home more often than a flashlight too.

How do I pack a cooler?

Fill it with beer. Done.

Actually, there are a few techniques to help you get the most cooling possible from your cooler. First, when you start packing the cooler, try to have it be as cool as possible. If you’re at home, an hour before you want to pack the cooler, throw something out of your freezer (a few ice cubes or a bag of frozen vegetables) into the cooler and shut the lid—this will cool it down. Second, be organized and get the cooler loaded all in one go: put down some ice, put your beer on top of that, add some more ice, some food, then a little more ice, then shut the lid and load it into the car. Taking an hour to pack it and repeatedly opening and closing the lid will lower the temperature. Third, the ice that turns into water is almost as cold as the ice itself, so don’t get overzealous with draining the cooler—do it only when necessary. Fourth, keep the cooler cold once you’re outside. Put the cooler in the shade during the day, and minimize opening and closing it—when you get up to get yourself a beer, ask if anyone else wants one. That’s just the nice thing to do anyway.

How do I cook in a Dutch oven?

A Dutch oven is a heavy, three-legged cast-iron pot with a lid that can revolutionize your camp cooking if you’re willing to put in the effort to lug one around and also to learn how to use it. If you can cook something in a slow cooker, you can cook it in a Dutch oven, and if you can bake something in a regular oven, you can probably bake something similar in a Dutch oven.

To use a Dutch oven, you’ll need a campfire, a bag of charcoal, a set of tongs, a pair of leather gloves, and, for best results, a recipe that’s designed specifically for Dutch oven cooking. For your first time cooking in a Dutch oven outdoors, try something simple like canned biscuits or a chocolate cake from a simple box mix. The Dutch oven works by cooking from both above and below, so you’ll need an area of a campfire where you can build a small nest or seat of hot coals in which to set the Dutch oven.

Heat up the charcoal in a side spot of the campfire bed, coat the inside of the Dutch oven with a small amount of cooking oil, and mix up your chocolate cake mix or open your biscuits. Put the cake batter or biscuits in the Dutch oven, and place the Dutch oven on top of the hot coals. Put the lid on the Dutch oven and place some hot charcoals on top of the lid, building an even layer. Monitor the cake/biscuits every few minutes to see how they’re cooking—it’s a good idea to rotate the Dutch oven in the bed of coals to make sure it’s cooking evenly throughout the process. Once the cake/biscuits are done, clean out the Dutch oven with only water (no soap). Once you’ve mastered an easy recipe like cake or biscuits, you can make more complex meals like soups or stew.

What kind of tent should I buy?

There are a bajillion different tents on the market, costing from $25 to $10,000 (really). As with everything else, the more you spend, the higher the quality of the product you can expect to get, but how much do you need to spend if you’re not going to Mount Everest and camping locally? Generally, spending a minimum of $150 to $200 will get you a tent that won’t leak or break on you with regular use. To decide which type of tent you need, you’ll want to consider how you’re going to use it: Will you take your whole family camping and need enough space for six people, or will it just be you and one other person sleeping in the tent? If you’re going to be backpacking, a giant six-person tent you can stand up inside is not going to be very useful, because it will weigh 30 pounds and you won’t want to walk too far with it in your backpack (if you can even fit it inside your backpack). A good, basic tent that’s good for backpacking as well as car camping would be a small, two-person tent that weighs around or under 5 pounds—big enough to sleep two people but not luxuriously huge (more of a sleeping room than a living room). At 5 pounds, it can be packed in a backpack and not feel as though it’s crushing you. A basic but quality two-person tent will cost $150 to $300 and will come with poles, a rain fly, and stakes, and you can confidently take it on weekend car camping trips as well as weeklong backpacking trips and be sure it won’t burst a leak or blow over in gusty winds. For an extra $25 to $60, you can also buy a tent footprint, an extra layer of fabric that clips onto the bottom of your tent to protect the floor of the tent from punctures. Make sure you buy the footprint that corresponds to your exact tent brand and model—any other footprint likely won’t integrate with the shape of your tent.

How do I pitch a tent?

If you can, it’s best to just convince your friend to set up your tent while you sit down and rest or take a nap, but if you can’t do that it’s good to know how to pitch it yourself. Tent designs are varied, and each one has its own specific setup protocol, but most contemporary tents are extremely user-friendly and won’t take more than five minutes or so to set up. In general, the basics of pitching a tent are as follows.

• Locate all the parts. Tent body, rain fly, tent poles, tent stakes. As you’re setting up the tent, make sure the lightweight tent body and tent fly are weighted down and won’t blow away in a gust of wind.

• Lay out the tent body. Figure out which side is the bottom and which side is the top (the top will be made mostly of mesh), and lay it out where you’d like to sleep for the night—a flat spot free of sharp sticks and rocks.

• Set up the poles. Almost all tent poles are made of a number of short sections connected by bungee cords and will snap together quite easily as the end of one section fits inside the end of the next section. Be careful that each pole section is fully inserted into its neighbor—if not, it’s possible to break the tent pole.

• Insert the poles into their proper places in the tent. The poles will slide into either nylon sleeves or plastic clips, and the ends of the pole will pop into grommets near the bottom of the tent. As you do this, the tent will begin to take shape.

• Attach the rain fly. The rain fly will attach to the tent body via clips or hooks. Make sure that it’s attached securely and evenly and that the doors of the rainfly match up with the locations of the doors on the tent body.

• Stake it down. First stake down the tent body, then the doors, then the guylines. Make sure the tent is as taut as possible—any loose sections of the tent will make a lot of noise if the wind picks up in the night, and setting it up correctly in the first place is far better than getting out of your warm sleeping bag in the middle of the night to readjust the stakes and guylines because the tent is flapping in the wind.

What do I do if the ground is too hard to get tent stakes into?

If you’re camped on hard-packed dirt or a flat rock surface, driving tent stakes into the ground can be difficult or impossible. Fear not, and consider a few options.

• Move your tent to a spot with softer ground so you can put in the tent stakes.

• If you’re in a spot with sufficient tree cover that acts as a solid windbreak, you can probably get away with staking down only the doors of your tent. Keep your gear inside the tent to weigh it down, or carry two or three heavy rocks inside the tent to weigh it down when you’re not inside it (your body weight will hold it down when you’re in it), and set the rocks outside the door when you turn in for the night.

• Stake it down with rocks. If your tent has a sufficient number of guylines, you might be able to use only the guylines to secure it. Find the biggest rocks you can carry and place them around your tent. Wrap each guyline around a rock and tighten it so there’s no slack. Pay attention to your tent’s position—if it’s sheltered from the wind, you might be okay with minimal stake-down points. If it’s not, consider moving. Just because there’s no wind at 4 p.m. when you’re setting up camp doesn’t mean there won’t be 35 mph gusts at midnight. Move the rocks back when you’re done.

• Tie your guylines to nearby trees.

How do I set up guylines?

When you pulled your brand-new tent out of the bag for the first time, you probably noticed some cords attached to the rainfly in a few spots and thought, “What are these?” They’re guylines. If utilized, they help stabilize your tent in windy weather, help the tent ventilate, and keep the rainfly from touching the tent body and building condensation. You will also likely trip over one of them at some point. But they’re useful, and in a storm they can mean the difference between your tent poles snapping and your tent poles staying intact. A few pointers:

• When you bought your tent, it probably came with too few stakes to utilize all the guylines (this is a regular, if mysterious, practice). The tent also was probably built with several tabs that can optionally be used to tie guylines to, but no cord to make guylines with. Do yourself a favor, and before you leave the store, buy four or five additional tent stakes and 40 feet of thin cord so that when you get your tent home you can utilize all those guyline options.

• You don’t have to tie guylines to every single spot on your tent, but a minimum of four guylines will do wonders to keep it upright in gusty weather. If your tent’s rainfly has tabs or loops where the fly runs over the tent poles (and it should), utilize those spots first—they oppose each other and basically pull the tent in four different directions to anchor it down and add stability.

• You stake a guyline down just as you do a tent: pull the cord taut and push the stake into the ground at about a 45-degree angle, with the top of the stake pointing outward away from the tent.

• After you stake down the first guyline, do the opposing guyline next (the one diagonal from the corner of the tent you just staked down). Then do the last two guylines.

• Guylines are wonderful, but they are not superpowered—don’t set your tent up in an exposed place (a mountain ridge with no windbreak, for example) and expect guylines to keep you safe. Use them as a safeguard, not a substitute for good judgment.

• You’ll likely have to adjust the tension of your guylines during a stormy or windy night. The best way to do that is to have them tied with an easily adjustable knot like a trucker’s hitch (see below).

How do I tie a trucker’s hitch?

The trucker’s hitch is a knot that was traditionally used to tie down loads to truck beds, and it works just as well to secure your tent to the ground. The magic is that it’s adjustable after it’s tied, so it’s great for guylines that need to be retightened throughout the night. Tying a trucker’s hitch might seem complicated at first, but it will become your new best friend once you master it.

• Tie one end of your guyline cord to your tent, pull the cord out toward the ground, and put a stake in the ground at about the halfway mark on the cord (this is not necessarily the final spot where you’ll stake down your guyline). Pull the cord out and loop it around the stake so you are pulling the loose end of the cord back toward the tent.

• On the strand of guyline between the tent and the stake (not the loose end), tie a figure eight on a bight knot about halfway up.

• Take the loose end of cord and run it through the loop of your figure eight on a bight knot. Pull the cord tight, and secure it to both strands of cord with two half-hitch knots.

• You now have a trucker’s hitch. Find the optimal spot for your tent stake, and vary the length of your guyline accordingly—you want the guyline as taut as possible, but with enough room to adjust it when it needs to be tightened later. You may have to untie the trucker’s hitch and start over if your initial figure eight on a bight knot is too close or too far from the tent.

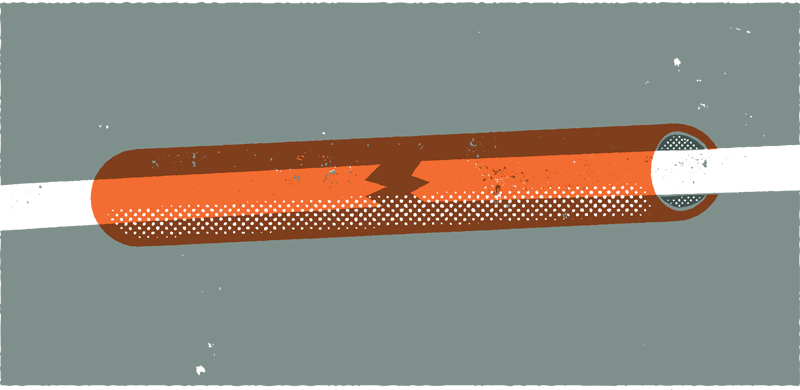

What do I do if I break a tent pole?

Almost all decent backpacking tents come with an emergency pole repair sleeve, a cigarette-sized aluminum tube that slides onto a broken section of tent pole to stabilize it. If your tent didn’t come with one (check the bag the stakes came in), you can buy one at most outdoor stores for about five dollars.

When you snap a pole, carefully pull it out of the tent. It will probably have sharp edges, so make sure you don’t snag it on anything that it can tear—which is pretty much every inch of fabric on your tent. Slide the repair sleeve up the pole until it’s centered on the broken spot, and use a small strip of duct tape on each end to hold it in place.

If you don’t have a pole repair sleeve, the best you can probably do is use a tent stake (you can very likely spare one from your tent unless you’re camped in an extremely windy spot) or a very stiff stick to splint the pole where it’s broken—wrap it tightly with a few feet of duct tape.

How do I rig a tarp?

A tarp is the most minimalist and often the cheapest camping shelter option—besides sleeping in a cave. All you need is a 10-by-10-foot tarp, 50 feet of lightweight cord, and eight tent stakes. There are many different configurations to rigging a tarp, but the simplest and most stable is the A-frame pitch.

To rig your tarp, find two trees with a flat space between them (or at least a space flat enough that you can sleep on it without rolling downhill all night). Tie a long length of cord between the trees so it’s taut and about 4 feet above the ground in the middle. Flip the tarp over the cord so the cord splits the tarp in half, and tie short sections of cord to each corner grommet. Stake the corners of the tarp down so it forms an A-frame roof over the ground, and when the tarp is taut, tie cord to the other grommets along the edges of the tarp that are touching the ground, and use your remaining stakes to stake them out.

Rain will come in the ends of your tarp, so don’t set up your sleeping bag so your head is near either end—put your sleeping bag more toward the center of your A-frame so you’re covered.

Can I sleep outside without a tent or tarp?

If you really do want to sleep out under the stars, as in when you open your eyes in the middle of the night, you see stars, you can ditch your tent. But if you ditch your tent, you’ll want to take into consideration a couple of things, the first of which is (maybe quite obviously) the weather forecast—if it rains, you’re going to get soaked if you’re sleeping in an unprotected sleeping bag (almost no sleeping bags are made waterproof enough to withstand much of a rain shower). So pick a night where there’s a minimal chance of rain and go for it. But also remember that you won’t have any protection from bugs if you don’t have the mesh of a tent between you and any mosquitoes or other insects that might like to feast on your blood or just crawl around on your face. If you’re squeamish about spiders or other creepy-crawlies, you might consider the alternative of sleeping under the stars, which is setting up your tent but leaving the rain fly off. That way you’re still sleeping under the stars, obstructed only by a layer of see-through mesh.

Can I cook in my tent?

If it rains, or if it’s so cold you don’t want to get out of your sleeping bag to cook dinner or breakfast, you might think it makes sense to bring your stove inside your tent to cook. Don’t do it. Cooking inside a tent on a canister stove can easily produce enough carbon monoxide to kill you, not to mention melt or burn your sleeping bag, sleeping pad, and the tent itself. Cooking inside a tent on a white gas stove is an even bigger risk for fire. If you absolutely have to cook without leaving your tent, place the stove outside under the rain fly under one side of your tent door, and leave the other half of the door open. If your tent has a second door, open the door on that side for ventilation. Be careful with hot liquids and hot pots near the tent—just touching the tent fabric with something hot will melt a large hole in it.

How do I brush my teeth when I’m camping in the backcountry?

Brushing your teeth in the backcountry will teach you how little water you actually need to get your teeth clean. Use a small amount of toothpaste and a tiny amount of water on your toothbrush, and when you’re done, blow the toothpaste spit out of your mouth in several bursts, pursing your lips tightly so the spit vaporizes as much as possible (nobody wants to see a pile of toothpaste spit in the backcountry). To rinse your toothbrush, pour a little water out of your water bottle onto the bristles, or pour an ounce or two of water into your mouth and forcefully spit it through the bristles to rinse it out. Yes, your brush might not get 100 percent clean, but your teeth will.

What happens if I get a hole in my tent?

If you get a hole in the rain fly of your tent, it’s not an issue—until it rains, and that could be the next night of your trip. In that case, your first instinct might be to duct-tape the hole, but the old maxim that duct tape fixes everything is not exactly true. It can work for a short time, but for a real repair job that will actually hold, it’s best to carry and use a field repair kit (which costs around eight dollars and weighs a couple of ounces). A field repair kit should contain a small tube of a product called Seam Grip or an equivalent, and a couple patches made of waterproof material. This will repair small holes in your tent fly. If you manage to rip a hole larger than about 2 inches in diameter, duct tape might be your only option (along with really hoping it doesn’t rain) until you can seek out a professional repair when you get home.

If you rip a hole in the body of your tent, including the floor, use the same repair kit to fix it. If you rip a hole in the mesh of your tent, it’s not as much of a big deal in the field (unless you’re camping in an area with tons of mosquitoes or other insects that will fly in through the hole). Either leave it as is or patch it with duct tape, and when you get back home find a mesh repair kit in an outdoor store or online and fix the hole.

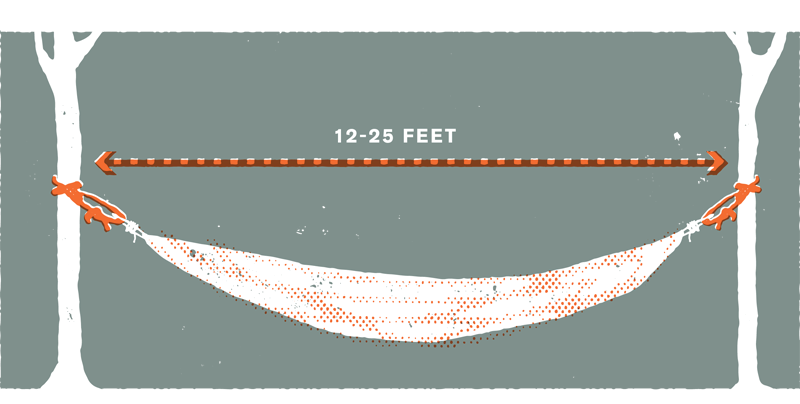

How do I put up a hammock?

Hanging a hammock is simple, right? You just hang it up between two trees and voilà, you’re done. Not so fast. There’s actually some math that goes into it, and your particular hammock should come with instructions specific to the measurements of the hammock. Here are the basics you’ll want to know:

• Always use webbing straps to attach a hammock to trees. These are simple strips of webbing with loops at the ends to run cord through. Find two trees roughly 12 to 25 feet apart and around 8 inches in diameter or slightly smaller. Wrap one of your two webbing strips around the tree trunk at about shoulder height so that the webbing wraps around twice and the loops are facing the direction where you’ll hang the hammock (the space between the two trees).

• Your hammock has a cord on each end (one on the foot end, one on the head end). Pick an end and estimate how much cord you’ll need to hang the hammock evenly between the two trees, and tie it to the webbing with a couple of half-hitch knots (see here). Don’t worry; this isn’t your final position, so don’t tie the knots too tight—just enough to keep it in place while you figure out the exact position of the hammock.

• Wrap your second strip of webbing around the other tree, and run the cord from the opposite end of the hammock through the loops in the webbing. Tie a couple of half hitches in the cord just as you did with the other side, and step away from the tree and eyeball the hammock. Is it hanging with an even amount of cord on each side? If not, adjust your half hitches until it is. The hammock should be hanging at a height where you can sit down in it from a standing position—if it isn’t, move your webbing straps up or down the tree trunks as appropriate.

• Once you’ve got the hammock in the correct position, secure it to the webbing. Untie your half hitches and begin lashing the cord to the webbing. Pull the cord taut and wrap the tail (the loose end) under the section of cord running from the webbing to the hammock, then bring it back up and across the cord. Run the tail through the webbing, between the two loops, and bring it back toward the hammock, pulling it tight. Repeat this process four times, pulling the tail tight each time. Tie up the loose end with a couple of half hitches. Lash the cord on the other end of the hammock in the same fashion.

What’s a bivy sack?

Bivy sack is short for bivouac sack, a minimalist waterproof shelter that is used instead of a tent or tarp (or sometimes in combination with a tarp). It’s the same shape as a sleeping bag and is large enough to fit a sleeping bag inside. If you choose to use a bivy sack in lieu of a tent or other shelter, you are likely doing it to save weight in your backpack. The advantages are that it is lightweight and easy to pack (no tent poles, no stakes), and the disadvantages are that the inside of a bivy sack is a small place to spend a long rainy day or night—you generally can’t sit up in a bivy sack, and if it’s raining you will want it zipped almost all the way up with you inside it (don’t worry, you’ll still be able to breathe). You also lose the ability to shelter your gear from the rain—with a tent, you can always shove your pack and cooking gear inside during a rainstorm, but in a bivy sack you don’t have that space. But bivy sacks can be great if you’re on a trip with little chance of rain and you want to keep your backpack as light as possible—even the heaviest of bivy sacks weighs only 2 pounds, compared to most tents, which weigh 3½ to 6 pounds.

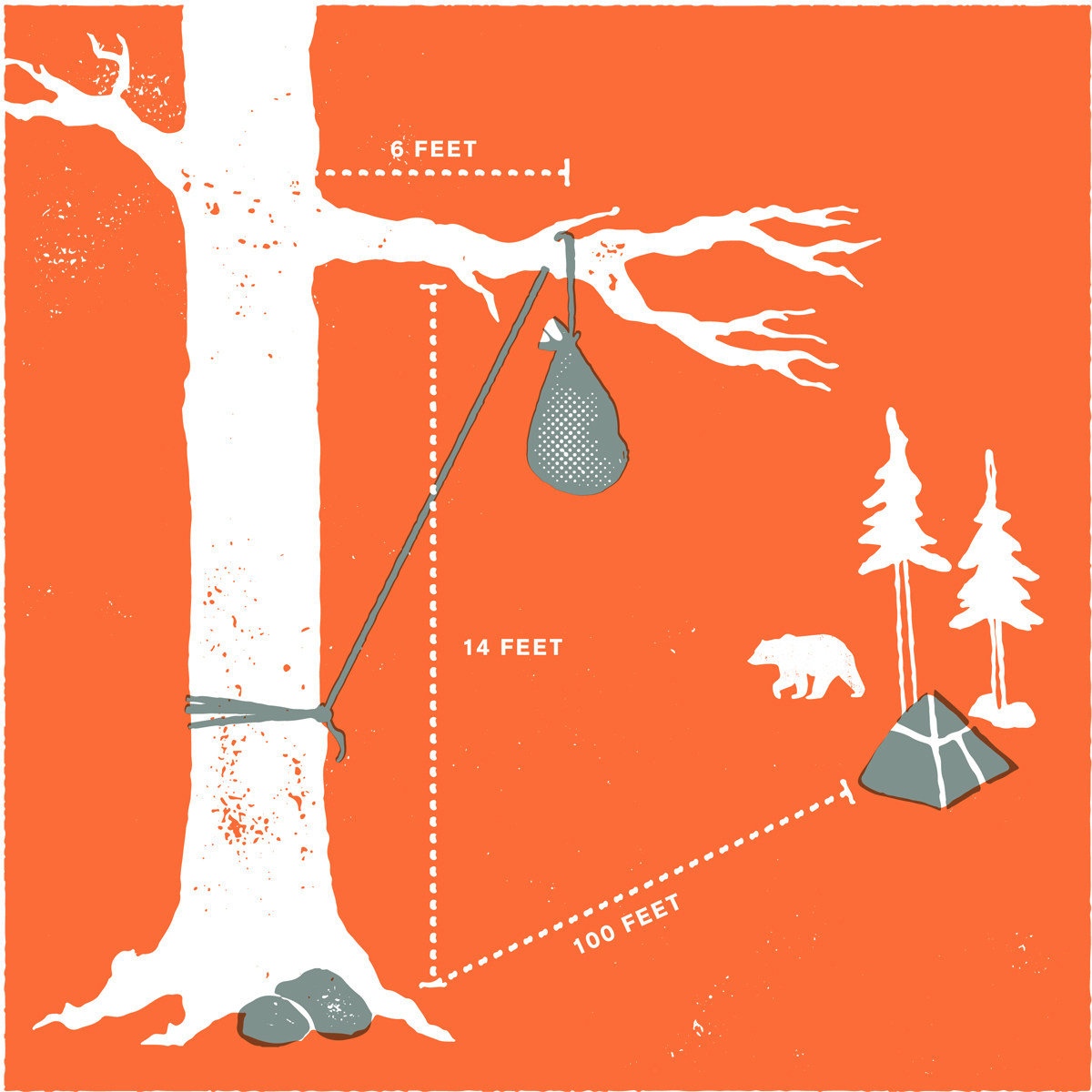

Should I keep the tent in the bag it came in?

Your backpacking tent probably arrived in a nice sleek bag, and you might think that it would make a nifty little package to strap to the back of your backpack. It might, but then you’re putting a bunch of weight on the outside of your pack, and that weight will pull your pack backward. Plus, the tent poles will be on the outside of your pack, and if you accidentally set your pack down hard somewhere, the poles are in an unprotected spot and can bend or break (not good). It’s better to remove the tent body, rain fly, poles, and stakes from the bag, leave the bag at home (or bring it along to use as a bear bag—see here), and pack the tent in your backpack in pieces—or split the tent in half and give part of it to your backpacking partner to carry (one person gets the poles and fly, the other gets the stakes and the tent body). When you get home, store the tent back in the bag.

How do I clean out my tent?

In the backcountry, hopefully you’re able to keep from spilling food and liquids in your tent (because bears like that sort of thing). So most of the things you want to clean out of your tent should be dry solids—pieces of grass, dirt, and small rocks that got into the tent as you were moving in and out of the door. The easiest way to clean out the tent is to wait until the next morning when you’re packing up camp. Take your tent stakes out of the ground, remove the rain fly, unzip the door (or both doors), pick up the tent by the poles, lift it over your head, and shake it, letting the dirt fall out the open door. If you want to do an even better job, take out the poles, turn the tent body inside out, and brush the dirt off the floor with your hand.

Once you get home, if you need to do further cleaning, set up the tent in your garage, front yard, or living room, and wipe it out with a wet paper towel or rag. You shouldn’t need to use any sort of cleaning product unless you spilled something nasty in there—but if you do, use a little soapy water, which won’t damage the fabric of your tent floor.

What do sleeping bag temperature ratings mean?

Strangely, sleeping bag ratings have always been a bit nebulous. For years, there was no universal rating system, and one manufacturer’s 30-degree rating (meaning that you could comfortably sleep in the bag in weather 30°F or warmer) was something far different than the next manufacturer’s 30-degree rating. Thankfully, many (but not all) sleeping bag manufacturers have started to use the EN (European Norm) methodology, which is used to test sleeping bags and establish their true insulative value. However, the rating is not printed on the sleeping bag—you’ll find it on a tag attached to the bag. The EN system lists three ratings for each sleeping bag.

1. The Comfort Rating (for women) is the lowest outside temperature at which an average woman will stay warm inside the sleeping bag.

2. The Lower-Limit Rating (for men) is the lowest outside temperature at which an average man will stay warm inside the sleeping bag.

3. The third rating, the Extreme Rating, is the lowest outside temperature at which an average woman can survive in the sleeping bag.

How does that relate to a manufacturer’s rating of sleeping bags? For one sleeping bag that the manufacturer itself rated as 15 degrees, for example, the EN ratings were as follows:

• Comfort Rating: 27.1 degrees

• Lower-Limit Rating: 15.6 degrees

• Extreme Rating: -17.5 degrees

Should I get a down or a synthetic sleeping bag?

Most sleeping bags will fall into one of two categories, according to the type of insulation they contain: down (plucked from geese), or synthetic (some type of synthetic insulative fiber). There are advantages and disadvantages to both.

Down sleeping bags are almost as a rule more lightweight and compressible than synthetic sleeping bags. Because down is extremely compressible, down sleeping bags pack smaller in your backpack. They’re also more expensive, starting at around $250 for a low-end bag and running nearly $1,000 for a high-end, custom-made sleeping bag. A major disadvantage to down sleeping bags is that when down gets wet, it loses its insulative capability, so if your bag gets soaked somehow, whether by a rainstorm or a leaky water bottle or a fall during a river crossing, you’ll be in trouble. Many companies have started to make “hydrophobic” down, which is not waterproof but will resist soaking and dry more quickly than regular down. This can be good in damp camping conditions but still takes a long time to dry in the event of a full soaking. Down sleeping bags are a great choice for adventurers who are conscious of the total weight of their backpack (backpackers and climbers in particular) and people who spend most of their nights camping in dry environments like the desert or the Rocky Mountains.

Synthetic sleeping bags are usually less expensive than down sleeping bags but are heavier and bulkier (although gear companies are perpetually making lighter and more compressible synthetic bags). Synthetic insulation, unlike down, will hold some of its insulative properties when it’s wet, so synthetic bags are a good choice for adventurers who spend more time in wet environments where they’re likely to deal with rainy or snowy weather multiple days in a row. Synthetic bags are also appropriate for people who are less worried about weight or space (kayakers or whitewater raft enthusiasts) or who are just more concerned with warmth in all conditions (snow and rain) than they are with weight and space.

What’s the difference between a $50 sleeping bag and a $250 sleeping bag?

Yes, you could save a lot of money on camping gear by buying it all at a discount department store that also sells toasters, jumper cables, and Christmas decorations, but it might not last that long or work that well. The primary difference between a $50 sleeping bag and a $250 sleeping bag is performance. An inexpensive sleeping bag is likely to be a rectangular-shaped bag with a large opening at the top. This lets in lots of cold air, which makes you cold and probably means you’ll have a night without sleep and a general dislike of camping. A mummy-style bag of any quality will insulate better than a rectangular bag simply because it has a much smaller opening at the top and less dead air inside for your body to heat up. A $50 bag will also probably not have quality insulation or zippers, and zippers can be the bane of your existence if they don’t work correctly. If one breaks, you can pay half of the cost of your $50 sleeping bag getting a new zipper put in it.

And, as with a lot of inexpensive things, durability will be an issue. If you want to go camping five times in your life, buy a $50 bag. If you want to go camping twenty-five or more times, spend some extra money and get yourself a quality sleeping bag.

How do I wash a sleeping bag?

A sleeping bag might seem straightforward to clean (isn’t it just like a duvet?), but it requires a little extra care so you don’t ruin your investment. You don’t need to wash your sleeping bag every single time you use it. Unless you really stank it up somehow, washing it once every twenty or thirty nights of use (or once a year) will keep it from getting too funky. It’s best to avoid washing it in a top-loading washing machine because the cords on your sleeping bag can get caught on the spindle and wreak havoc on the bag, and the agitator can rip apart the stitching. So use a front-loading machine. If you don’t have one, head to a laundromat and use a front-loader there. Wash the bag in cold water, on a gentle cycle, using a nondetergent soap. When it’s done, put it in a dryer set on no heat (not low heat—no heat) with a couple of tennis balls or dryer balls. Without something bouncing around the dryer to break up the clumped down (or synthetic insulation), it will just stay clumped and take days to dry—plus you’ll have to break up all the clumps by hand. Your sleeping bag works only as long as it has loft and the insulation is evenly spread throughout it, and improperly drying it can ruin the distribution of insulation.

How do I store my sleeping bag at home?

Your sleeping bag should come with two bags with drawstring closures: one big (possibly mesh) bag of about the same dimensions as a queen-sized pillowcase, and one “stuff sack,” which you should use to compact the bag and carry it in the bottom of your backpack while you hike. Storing the sleeping bag in the stuff sack for prolonged periods of time can nearly permanently compact the down so it has almost no loft (or it can take weeks for it to regain the loft once you pull it out of the tightly compacted storage)—so keep it in the bigger, mesh bag at home, or better yet, store the bag completely rolled out if you have enough space to lay it down somewhere or hang it from its foot end.

How do I store my tent when I get home?

When you get home from your backpacking trip, it’s a good idea to set up your tent in your garage, backyard, or living room for a day to make sure it’s 100 percent dry before you put it away—mildew has caused the premature death of many tents. If it’s clean and dry, store the tent in the bag it came in when you bought it. Some people like to neatly fold and roll up the fly and tent body, wrapping them around the tent poles before sliding them into the bag, and some people just stuff the tent in the bag around the poles. Neither way has been proven to be superior for any significant reason—although folding it generally leaves the tent with fewer wrinkles and creases (or at least neater-looking wrinkles and creases) the next time it comes out of the bag for camping use.

What should I do if my sleeping bag gets wet on a camping trip?

If your sleeping bag gets wet on a camping trip and you’re camping for another night, you’ll have to do your best to dry it out. If it’s a synthetic sleeping bag, find a sunny spot and ideally a tree branch to hang the bag over so the sun and the breeze can dry it out. If you can’t find a tree branch that will hang the bag facing the sun, lay it out on a dry rock. If it’s a down sleeping bag and it got wet, do the same thing—hang it on a tree branch in the sun. If the down insulation in the sleeping bag got wet enough that it has clumped inside the bag, break up the clumps by pinching them with your fingers. As the bag dries, keep working to break up the down. It may take several hours for the bag to dry, especially in a humid climate.

If your sleeping bag gets wet and it’s the last day of your camping trip, don’t worry about getting the bag dry before you head home. Pack it away, and when you get home hang it up to dry or put it in a clothes dryer on a “no heat” (not “low”) setting. If it’s a down sleeping bag, make sure to place two tennis balls in the clothes dryer to bounce around and break up the clumps of down.

How do I sleep (comfortably) in a sleeping bag?

There’s no sleeping system that can really approximate your bed at home, and the sooner you understand that, the better off you’ll be. Instead of trying to replicate a bedlike experience, learn to sleep in a sleeping bag with a few basic tips. Understand that you’ll be zipping yourself into a bag, and you won’t be able to spread out your limbs and starfish like you can in a bed. That’s the bad news. The good news is, a decent sleeping bag will keep you warm as the temperature drops to below freezing. Follow these tips to make your sleep more comfortable.

• Make a pillow by putting your extra clothes inside a stuff sack and put it under your head, either inside your sleeping bag hood or outside it.

• Zip up your sleeping bag, get all your limbs inside, and make sure you’re not breathing into the bag itself (condensation on the inside will make you cold). To prevent this, when you roll onto your side, roll so the bag rolls with you, not so your head turns facing away from the opening. The smaller you make the opening around your face, the warmer you’ll be—in extreme cold, your nose and mouth might be the only things poking out.

• If your socks are wet or damp when you go to sleep, either put on dry socks or just take your socks off your feet (they’ll dry overnight inside your sleeping bag).

• If you wake up in the night and you’re too warm, work your way out of the bag in increments: often just popping your head out is enough to cool you down to a comfortable temperature. If it’s not, unzip the zipper six to twelve inches and see if that works. Then try sticking one arm out, and so on.

• You’ll likely wake up in the night more times than if you were sleeping at home. That’s normal; just accept it as part of sleeping outdoors.

What kind of sleeping pad should I buy for underneath my sleeping bag?

There are three basic choices when buying a sleeping pad: foam, self-inflating, and air pad. A foam pad is the least technologically advanced, lowest cost, lightest weight, and usually lowest comfort of all the options—it’s basically just a ½-inch-thick strip of closed-cell foam, which is fine for a lot of people. You can also skip the foam pad and find a campsite with some natural cushion under it (such as pine needles or grass). A self-inflating pad is generally an inch or more thick and will fill itself with air at least partially—but you’ll need to blow it up by mouth to get it completely inflated. Self-inflating pads are more comfortable than foam pads and generally warmer and more durable than air pads (but a little heavier than both foam pads and air pads). An air pad that you inflate by blowing air into it with your mouth is the most cushioned and usually the most lightweight option—think of a pool air mattress, but a bit more high-tech and durable. It’s generally 2½ inches thick or more, which is a luxurious amount of padding in the backcountry, but it can be cold unless it has an insulating material inside its cells (all that air underneath you cools quickly overnight and can lower your body temperature, even through your sleeping bag). Many models of air pads puncture more easily than self-inflating pads, so they’re not the best for “sleeping out” without a layer of protection underneath them.

How do I roll up a sleeping pad to be as small as it was when I bought it?

When you buy a self-inflating sleeping pad, it’s tightly wrapped in vacuum-sealed plastic. This is the smallest it will ever be. Let go of any delusions that you will ever stuff an object that size in your backpack again. It’s impossible. The sleeping pad you bring home from the store was packed by a machine, and you are no machine. Don’t try to compete with it; instead, compete with yourself. See how small you can roll up your sleeping pad. To do this, unscrew the air valve and let the air seep out. Start slowly rolling the foot end of the pad toward the head end (or from the end opposite the air valve to the end with the air valve). Squeeze the air out as you go, and roll slowly enough that air has a chance to escape and doesn’t gather in the rolled part. When you reach the end and you’ve rolled up the pad completely, close the air valve so no air can get back into the pad. Unroll it again, fold the pad in half lengthwise (or in thirds, depending how it was originally packed), and start rolling from the feet end again. As you get closer to the top, you will have to open the air valve to let more air escape. Do that, and when you have the pad completely rolled up, close the valve again and tighten a strap around the pad to keep it compacted in your pack.

How do I patch a hole in my sleeping pad?

If you somehow get a hole in your sleeping pad, you’ll know. Halfway through the night, you’ll notice that you’re feeling much closer to the ground or that your hip seems to be sitting on something quite firm when you roll over (that’s the ground). To patch the hole, you need two things: a patch kit and the ability to find the hole.

When you bought your sleeping pad, hopefully it included a patch kit. If not, look up the manufacturer and purchase a patch kit from them—a patch kit is lightweight, inexpensive, and insurance against uncomfortable nights trying to sleep in your tent. The patch kit should consist of a small tube of adhesive and a few patches that match the material of your pad (if you buy the patch kit from the manufacturer of your sleeping pad versus buying another brand’s patch kit, it will match).

Finding the hole is the true crux—especially if you’re in the backcountry. Unless you have superpowers, you probably won’t be able to find it without sinking the pad in a body of water—the air pressure inside a sleeping pad isn’t usually enough that you can hear a hissing noise indicating air escaping. So when you have a chance, either before you leave camp or when you arrive at your next night’s camp (or when you pass by a pond or lake sometime during the day), inflate the pad and dip it into a calm body of water, watching for bubbles indicating the leak. When you find the leak, apply the adhesive around the hole (don’t be shy) and stick the patch on. Open the air valve on the pad, and leave the pad out to dry as long as the manufacturer’s instructions indicate. If you discover the hole on the last day or night of your trip, fix it at home: just fill up your kitchen sink or bathtub and find the hole, then patch it.

Should I share my tent with my friend?

Your relationship with your friend can, of course, dictate this—whether you want to get that close to him or her. But there’s no reason to have a hang-up about spending the night in a small tent with another person. It’s actually way better than sharing a bed with someone, since you’re both zipped into sleeping bags and no one can awkwardly, accidentally, try to spoon you in your sleep. One tent split between two backpacks means about 2½ pounds for each of you, whereas each of you bringing your own tent means 5 pounds each—that’s a lot of extra weight and bulk. Although it’s most economical to carry one tent, there are a few reasons why you’d want to take separate tents: your friend is a chronic snorer, or taller than 6 foot 6 and needs to lie diagonally in a tent, or maybe you’re on a trip that’s a week or longer and you each just want your own space.

How do I have sex in a tent?

Assuming you already know how to have sex, there are a couple of things that are different about doing it in the great outdoors as opposed to indoors:

• Air temperature: Just because you’re warm and toasty inside your sleeping bag doesn’t mean you can unzip it, get completely naked, and be comfortable. If it’s chilly outside at all, you might consider waiting until morning, when the sun will warm the air temperature significantly.

• Fluids: Washing a sleeping bag isn’t as easy as throwing a set of bedsheets in the dryer, so think about that when you’re about to get busy. If it’s warm enough, it’s a good idea to shove both parties’ sleeping bags aside, out of the way of any bodily fluids. Also consider that a wet spot inside a sleeping bag might be unavoidable when you zip yourself up in the bag afterward. Bring a wet wipe or two to clean up any stuff you don’t want sticking to your tent when you pack up camp.

• The ground: The ground is often harder than you might first think, especially on the back and knees. Try to push your sleeping pads together and eliminate gaps, and make sure knees aren’t rubbing against bare ground during the act itself.

How do I find firewood?

If you’re in an area where firewood gathering is permitted (i.e., Forest Service land, Bureau of Land Management land, or anywhere that doesn’t have a sign reading “Firewood Gathering Prohibited”), firewood gathering should be pretty easy. Grab a wide selection of different thicknesses of wood—a few twigs for kindling, a few finger-sized pieces to burn after that, then some “quarter-sized” pieces, or limbs about the diameter of a quarter, and then a few larger ones. If you’re in a heavily used backcountry area and can’t find firewood near your campsite, remember that most humans generally try to conserve energy and thus won’t go too far from camp to look for firewood. Grab a strap or piece of cord to bundle together any pieces of wood you’ll find, go farther out from your camp, and climb higher (most people don’t want to walk uphill to find wood). As you pick up pieces, strap them together, and when you’ve found enough, head back to camp and start your fire.

How do I split firewood?

Unless your fireplace is the size of a taxicab, you don’t want to be throwing a log as thick as your waist on your fire (no matter how trim your waist is)—big chunks of wood are hard to get lit, and when they finally catch they take forever to burn. So at some point you’ll need to split at least a few chunks of wood in order to build a fire.

For thick, round sections of wood 6 or 8 inches in diameter, you’ll want to use a splitting maul, a long-handled ax with a heavy, wide head. Take your chunk of wood and set it upright (it’s nice to have a chopping block underneath, but not mandatory). Inspect the top of the wood, where your ax blade will be hitting it: you want to aim your blade so it drives itself into the wood parallel with the grain, not perpendicular to it. Don’t worry about picking a specific line on the top of the wood and hitting it exactly—you won’t, and it’s not important. Just concentrate on lining up the blade and the grain. Don’t hit a knot, because you won’t get through it (the tree will almost always win that battle).

Stand facing the wood you’re going to split. Hold the maul with your nondominant hand (in this case, we’ll say your left hand) near the bottom of the handle and your dominant hand near the blade, with the blade pointing away from your thumb (or down toward the ground as you hold the maul parallel to the ground in front of your body). Bring the blade end of the ax back past your right hip and swing it up over your head, simultaneously sliding your right hand down the ax handle to join your left hand.

With both hands near the bottom of the handle, swing the maul into the wood. Don’t try to hit it as hard as you can—you will rarely get through a big chunk of wood in one swing, and you want to remain in control—firm, but controlled. Your elbows should be almost exactly straight when the ax blade hits the top of the wood. Aim for the center of the wood or slightly off center toward you (not away from you)—if you miss the center by too far toward the back, your ax handle will hit the wood, and most ax handles can’t endure too many hits like that. The blade will get stuck from time to time—when it does, slide one hand up the ax handle close to the blade and wiggle it out (you may even need to step on the wood with one foot and work it out using both hands). Keep swinging the maul into the same spot on the wood until it splits.

For smaller chunks of wood, you’ll want to use a hatchet, holding your small chunk of wood in your nondominant hand, using an abbreviated swing into the wood: lean over the chunk of wood, holding it in one hand and swinging the hatchet no higher than your head. Obviously be careful to avoid hitting your nondominant hand with the hatchet, and if you want to be extra-safe, stand the wood up in a stable spot and don’t hold it with your other hand when you swing the hatchet. If the hatchet gets caught in the wood on your first swing, you may not even want to bother pulling it out—simply swing the hatchet with the chunk of wood attached to the blade and slam it into the ground until the hatchet splits through the wood.

What kind of ax should I buy (a big one or a hatchet)?

As sexy as it is to whip a heavy splitting maul over your head and swiftly drive it through a chunk of wood, for general camping purposes it’s probably unnecessary, especially if you’re buying firewood from a gas station on your way to the campsite or making a fire from firewood you’ve gathered from the forest near your campsite. A small hatchet, or one-handed ax, will suffice to split your firewood into smaller pieces when necessary or to trim small branches from downed logs. Look for a hatchet with a 12- to 20-inch-long handle and toss it in the trunk of your car, where it will be for your next camping trip.

Do I need a saw?

For general backpacking purposes, you will probably never need a saw. If you’re building a campfire in the backcountry and you are burning pieces of wood you can’t snap in half by bending them over your knee or standing on them, you’re probably gathering wood that’s too big. If you’re car camping and bringing in your own firewood, a hatchet will probably do more of what you need (i.e., splitting logs into smaller pieces). That said, if you foresee some sort of need for one, get one that’s specifically designed for backpacking—they break down so they’re easy to pack, and they add much less weight to your backpack than a regular saw (some weigh less than a pound).

Should I take a machete hiking?

If you want to draw suspicious stares, or scare the crap out of other hikers, or have everyone talk about you after you pass them on the trail, you should definitely take a machete hiking. If you are reading this book, you will absolutely not need a machete when you go hiking. If you do need a machete where you go hiking, your trip is far beyond the scope of this book, and we will probably read about it in the pages of National Geographic, because your hiking is not in a fun place where trails are at least somewhat cleared prior to your hike, and you are hacking at vegetation with a machete to gain passage to something in the name of science or exploration.

Can I cut down a tree for firewood?

Putting your lumberjack/Brawny Man fantasies aside, cutting down trees for campfires is generally a bad idea for many reasons. Cutting down a live, green tree for firewood doesn’t usually work because the wood is so wet it won’t burn properly. Cutting down large dead trees can be dangerous unless you’re experienced at accurately felling them—meaning you can get them to fall in the exact spot you want, so that they don’t get hung up on neighboring trees or land on the hood of your car. And on Forest Service land, you can cut down trees for firewood, but you first have to have the proper permit. So bringing your own firewood, or gathering wood from near your campsite, is your best bet. If you want to hack away at a tree for a while, you should have no problem finding one on the ground that’s already been felled by Mother Nature.

How do I poop in the outdoors?

Pooping in the outdoors is a rite of passage: when you learn how to do it, the world opens up to you. You are no longer limited to short one-day hikes during which you will not have to worry about going number two. If you can poop in the woods, you can sleep in the woods, wake up the next morning, do your business, and hike for a second day, and repeat the process. So how do you do it?

First, you dig a hole. For this, you’ll need a small backpacking trowel, procurable at any outdoor gear store. With your backpacking trowel in hand, select a spot—ideally it’s private, 100 feet away from a trail, and 200 feet from water—and start digging. Make sure the hole you dig is at least 6 inches deep in order for your poop to decompose properly (and to bury it under enough dirt to keep its smell and sight hidden). It’s not a bad idea to anticipate your bowel movement and “pre-dig” a hole near your campsite for when the time comes.

Once you have a hole 6 inches deep, it’s time to do your business. Squat down and aim toward the bottom of the hole. If you need help balancing, extend a hand backward (watch out for the hole). And relax.

Congratulations. You’ve now pooped in the woods. Spread the dirt back over your hole and tamp it down. If you missed a little bit, grab a stick and nudge your stuff into the hole before burying it.

What do I do with my toilet paper?

You probably never give much thought to your used toilet paper. But in the woods you have to give a little more thought to where it goes, because you can’t just flush it away. Here’s the deal: not using toilet paper at all in the backcountry is the true mark of the expert outdoorsperson. Yes, for real. Sticks, rocks, leaves, even the occasional snowball work just as well, once you figure out your technique. This means you don’t have to carry toilet paper with you when you go backpacking.

However, few people achieve, or even aspire to, this expert level of outdoors pooping. So here’s what you do: take only white, nonperfumed types of toilet paper in your pack, and either bury it deep in the cathole you dug to poop in or pack it out with you in a sealed plastic bag. Try to minimize your toilet paper usage—don’t bury half a roll of it every time you poop, and maybe experiment with using a few squares of toilet paper only for “buffing” after you’ve tried using some sticks/rocks/leaves first. Of course, you’ll want to make sure you don’t wipe with poison ivy, poison oak, or poison sumac (see here).

Do not under any circumstances burn your toilet paper to get rid of it. Yes, it would disappear faster that way, but if you do it incorrectly (or if there’s a gust of wind at the wrong moment), you could burn down the forest, which is not worth the risk.

How do I toast a marshmallow?

The most important thing to remember in toasting a marshmallow over a campfire is that there’s really no right or wrong way to do it—just a matter of preferences.

Grab a stick about the length of your arm or slightly longer (unless you want to toast your forearm as well as the marshmallow), preferably with a semisharp end. If one end isn’t sharp enough to poke into a marshmallow without ruining it, take a minute and whittle the end down a little bit with your pocketknife.

Poke the stick into your marshmallow, and hold the marshmallow over the fire, keeping it in the edges of the flames. Watch the marshmallow and rotate it as it turns golden brown on each side. When you’ve achieved your level of toastedness (light brown, brown, dark brown, or black), pull the marshmallow out of the fire and give it a few seconds before biting into it.

An alternative method: Stick the marshmallow all the way into the fire until it catches on fire, then pull it out of the fire and blow it out. It’ll be singed, but gooey on the inside.

What’s the best way to make coffee in the backcountry?

Coffee is a very touchy subject among outdoorspeople, and everyone has his or her own opinion on how to make it best. Here are a few options and their pros and cons.

• Starbucks Via (or other instant coffee): Simple, easy, no wet grounds to pack out, no mess.

• Cowboy coffee (see here): Simple, easy, but gritty.

• French press: Makes wonderful coffee, but carrying the apparatus can be bulky, and there are lots of grounds to deal with.

• French press mug or French press attachment for cooking pot or Jetboil: Makes wonderful French press coffee and is less bulky than a regular French press, but there are still lots of grounds to deal with.

• Pour-over: Also makes wonderful coffee and isn’t very bulky but leaves lots of grounds (and filters) to deal with.

• Aeropress: Makes great espresso; is somewhat bulky but leaves less waste/grounds to deal with than other options.

• Abstaining from coffee: Ridiculous!

I absolutely love my French press—can I take it backpacking?

Here’s the great thing about backpacking: you can take whatever you want to take, no matter what anyone says. The only bad thing is that everything you want to take adds weight to your pack, so you have to make some choices or deal with a crushingly heavy pack. If you want to bring your special coffee-making apparatus because it’s the only way you can wake up, and when you get your coffee everyone on the trip will be better off, then do it. Think about jettisoning something else unnecessary if you need to make room for that moka pot (an extra pair of socks, a paperback book, deodorant, etc.). And when you hand your buddies a cup of wonderful espresso 5 miles from the nearest road, say, “I told you it was going to be worth it.”