THE HIDDEN SHAMAN

FICTIVE ANATOMY IN PALEOLITHIC AND NEOLITHIC ART

It has been suggested on more than one occasion that “imaginary animals, ‘monsters’, and composite figures are found throughout the Upper Paleolithic art tradition” that flourished among hunter-gatherers of the last Ice Age, between around 40,000 and 10,000 years ago.1 That tradition, or better complex of traditions, is most richly documented across a broad swath of southern Europe, on what were then the fringes of a vast steppe bordering the zone of maximum glaciation. Notable concentrations of Paleolithic imagery have been discovered in the French Périgord, in Cantabrian Spain, in the Swabian Jura, and on the Russian Plain. To the east of this distribution, they are mainly restricted to mobile objects with carved surface ornament—such as hunting tools, personal ornaments, and figurines in bone and ivory—while to the west, by no later than 13,000 BC, such objects are accompanied by spectacular paintings and engraving on rock surfaces.2

ORIGINS OF FICTIVE ANATOMY: PALEOLITHIC ART AND RITUAL

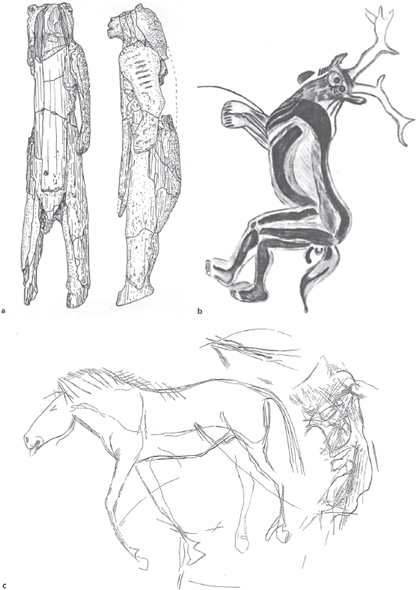

The presence, among this surviving corpus, of figures combining human and animal attributes plays an important role in recent debates over the significance of image making among early human populations.3 Among the earliest known is the so-called lion-man, a figure almost eleven inches high, reconstructed from fragments of mammoth ivory found toward the rear of a shallow cave at Hohlenstein Stadel, in the Lone Valley of southwest Germany (figure 3.1a).4 Dated by its associated archaeological deposits to around 30,000 years ago, it is among the oldest examples of mobile figural sculpture in the world.5 A still older sculpture of a standing figure has been unearthed from Hohle Fels, in the nearby Ach Valley.6 Despite its fragmentary state, comparisons have been drawn with the lion-man; but alternative interpretations of both figures remain possible.7

A clearer example of a figure with mixed human and animal attributes appears on an engraved plaque found at Etiolles, in the Paris Basin, positioned behind a carving of a horse (figure 3.1c).8 Dated to around 12,000 years ago, it belongs to the final stages of the Upper Paleolithic, as the last major phase of glacial climate was drawing to a close. The special nature of this object is further indicated by its archaeological context. It was found face down, and seemingly deliberately hidden, beneath a supporting block of a prehistoric hearth. Of similar, or slightly earlier, date is the carved and painted image often referred to as the “Sorcerer,” found deep within a network of subterranean passages at Les Trois Frères, in the Ariège uplands of southern France. The original was probably executed around 14,000 years ago, but the image that still features in most scholarly and popular publications was created by the Abbé Henri Breuil in the early twentieth century (figure 3.1b).9

Breuil, whose copies of prehistoric rock art have been widely influential, followed the interpretive paradigm that was prevalent in his day.10 This emphasized the magical role of animal images in increasing the fertility of herds and the success of hunting, a view now widely rejected in light of the lack of correspondence between species most commonly depicted in cave paintings (such as bison, horses, and mammoth), and those whose physical remains are most frequently reported from habitation sites (notably reindeer). The conditions under which Breuil recorded rock art were often, by his own admission, difficult, and some of the techniques used were at best simple. In the case of Les Trois Frères, a period of twenty years elapsed between the making of the copies and their publication, which often involved redrawing by a collaborator who had never visited the caves.11

3.1. (a) Ivory statuette from Hohlenstein-Stadel, Germany, ca. 30,000 BC; (b) the Abbé Henri Breuil’s rendering of a carved and painted figure known as the “Sorcerer” from Les Trois-Frères cave, France, ca. 12,000 BC; and (c) engraved plaque from Etiolles, France, ca. 10,000 BC (after Hahn 1986, p. 247, pl. 17; Breuil 1952, p. 166, fig. 130; Taborin et al. 2001, p. 126, fig. 2).

Discrepancies between Breuil’s reconstruction of the Sorcerer and the original image, which lacks a number of the features he identified, were already pointed out some decades ago.12 Reservations have sometimes been expressed about the identification of other Paleolithic images, deemed to represent imaginary creatures or masked humans.13 Nevertheless, these figures remain central to recent interpretations of Paleolithic image making. David Lewis-Williams, for example, takes the presence of hybrid human-animal figures, or masked human figures, as support for his theory that much Paleolithic rock art was created as part of shamanic rituals involving altered states of consciousness, whereby human actors entered into close participation with ancestral spirits in animal form.14 Steven Mithen considers whether the much earlier creation of figures such as the lion-man might reflect a fundamental change in human cognition, taking place around 30,000 years ago or perhaps earlier still, and signaling the inception of a dual capacity for complex symbolizing and sophisticated social interaction.15

The prominence ascribed to such figures in interpretation is out of all proportion to their quantity. During the later phases of the Upper Paleolithic (ca. 13,000–10,000 BC), when archaeological traces of image making are first available in significant quantities, the record is dominated by detailed and anatomically accurate representations of living kinds: large mammals as well as smaller, but significant numbers of birds, fish, and (mainly female) humans. Among this extensive corpus of painted and engraved figures, it has proved difficult to identify images of beings with composite anatomies that are replicated with any degree of fidelity. Suggestions to the contrary are often bolstered by selective comparisons with the rock art of living or recent hunter-gatherers in southern Africa.16 In fact, such images are far from ubiquitous there, and their chronological range is unknown.17 Were we, in spite of this, to admit the more regular depiction of composites or masked human actors in recent rock art traditions, this would surely provide an instructive point of contrast, rather than a surrogate for the Paleolithic record.

Questioning the frequency of composites among the surviving corpus of Paleolithic art does not, of course, require us to postulate that its creators had anything other than fully modern minds, capable of communicating complex symbolic messages. Nor does it require us to reject interpretations that explore the significance of such images in the ritual life of prehistoric societies. It does, however, establish an important benchmark for studying their distribution in the archaeological record. The significant point, to which I will return, is that if such beings did populate the collective imaginary of early hunter-gatherers, then their presence was made manifest predominantly through ephemeral modes of display such as psychotropic visions and masked performances that have left few durable traces.

In searching for more positive evidence of such displays, we are obliged to probe below the surface of the land into the funerary record of Paleolithic and Mesolithic societies, with their often effusive ritual compositions of human and animal body parts (figure 3.2). Examples can be traced far back in time from the “shamanic” graves of later prehistory18 to the much older cross-species burials of the Carmel caves; the latter, dating to around 100,000 BC, bringing us almost to the dawn of the human story.19 But these ritual composites, which will remain an important feature of Neolithic funerary customs,20 find only the faintest of echoes in the surviving visual record. Perhaps there is something to be learned from that silence, about the limits set by early hunter-gatherers to the materialization of the invisible?

IMAGERY OF THE FIRST FARMERS

At what point in the archaeological record do durable images of composite beings achieve some wider currency? We might look with some optimism to the much more diverse record of Neolithic art. In doing so, my focus will be upon areas that would subsequently witness the emergence of the earliest cities and states. Those same regions of the Near East and northeast Africa have produced unusually dense concentrations of late prehistoric imagery, distributed across a wide range of media, and allowing us the privilege of a diachronic perspective on the millennia between the end of the last Ice Age (ca. 10,000 BC) and the beginnings of urban life (ca. 4000 BC).21

3.2. Mixed burials of human and animal body parts from sites of the Natufian period in Israel, ca. 10,000 BC: (a) elderly woman with fifty tortoise shells and parts of wild boar, eagle, cow, leopard, and martens, from Hilazon Tachtit (image by P. Groszman, from Grosman et al. 2008; courtesy L. Grosman); (b) adult (?)female with disarranged body parts and gazelle horn-cores, from Mallaha (Eynan; after Perrot and Ladiray 1988, fig. 32).

The period in question saw the domestication of cereal crops and herd animals, and the establishment of sedentary life across a significant part of the western Old World.22 In an influential study, Jacques Cauvin characterized these developments as “the birth of the gods and the origins of agriculture.”23 He was referring to a series of pronounced changes in ritual and symbolic expression that accompanied the early stages of plant and animal domestication in western Asia, and then spread—together with the farming economy—to neighboring regions. At the core of Cauvin’s argument was a contention that Neolithic representations of supernatural agency differed from those of earlier, hunter-gather societies. He perceived in the symbolism of the first farming communities an acknowledgment of remote and invisible deities: a new register of divinity, dominating and mastering a preexisting order of relations between humans and ancestral beings. With the “birth of the gods,” those ancestral figures formerly credited with the making of the cosmos were relegated to a lower plane of reality, closer to the material world of ordinary humanity. Hence, Neolithic villages became populated by the physical remains of human and animal ancestors, impinging on the most intimate spaces of the household, making new and complex demands upon the society of the living. Among those demands, we find the performance of labor-intensive rituals, which involved the cleansing and symbolic refleshing of skulls, and the provision of exotic materials—pigments, shells, and colored stones—which ornamented the bodies of both the living and the dead.

To what extent can this Neolithic birth of the gods also be considered a “birth of monsters,” or rather “composites,” to be precise? Was it among these societies, unprecedented in their willingness to intervene in the reproductive patterns of other species, that anatomical hybrids made a concerted entry to the world of images? The existence of such images among the surviving corpus of Neolithic pictorial art has been quite widely discussed,24 but in fact remains intriguingly difficult to substantiate.25 Among the few archaeologists to comment directly on this point is Klaus Schmidt, the excavator of Göbekli Tepe, a ceremonial center of the ninth millennium BC, located between the mountains and plains of southeast Turkey and within the broad zone where changes in hunter-gatherer lifestyles were under way that would lead, within a few centuries, to the adoption of farming.26

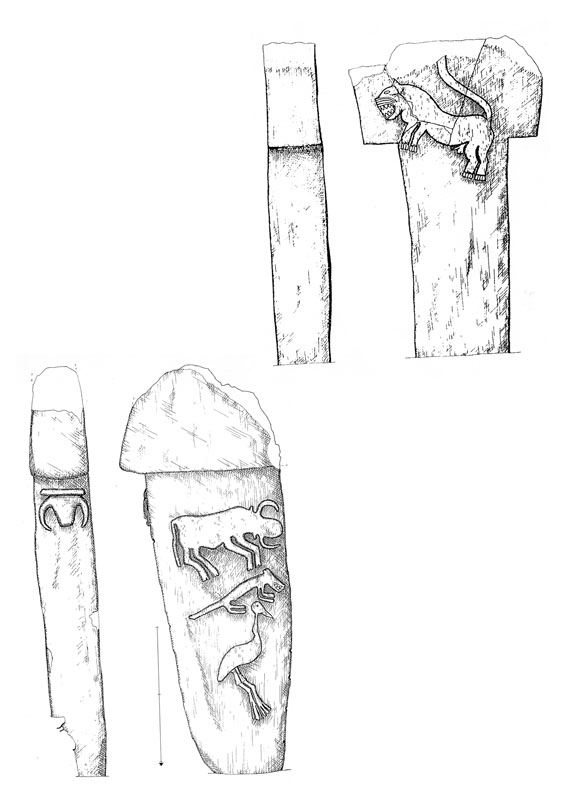

A rich assemblage of monumental relief carvings and freestanding sculpture was built into the stone architecture of this remarkable site. The figures, a selection of which are illustrated in figure 3.3, include an array of wild animals, such as lion and boar, some with a ferocious, almost nightmarish aspect. While bodies were often schematically rendered, faces were carved in some detail. Open mouths contain lolling tongues and carefully depicted rows of gnashing teeth: features that, even in royal hunting scenes, seem to have been avoided by the makers of much later urban monuments in the same region. Certain carvings, notably that of a bird that appears to sit and manipulate a round object, may ascribe human-like motor skills to animals. Others, such as the figure of a bull, are rendered in twisted perspective, with the body depicted in profile and the head as if seen from above. There is something undeniably otherworldly about this corpus of images, yet they make very little play on the possibilities of composite depiction.

3.3. Monumental animal reliefs on stone monoliths from the Pre-Pottery Neolithic site of Göbekli Tepe, southeast Turkey, ca. 9000 BC (after K. Schmidt. 1998. Frühneolithische Tempel. Ein Forschungsbericht zum präkeramischen Neolithikum Obermesopotamiens. Mitteilungen der Deutschen Orient Gesellschaft 130: 17–49).

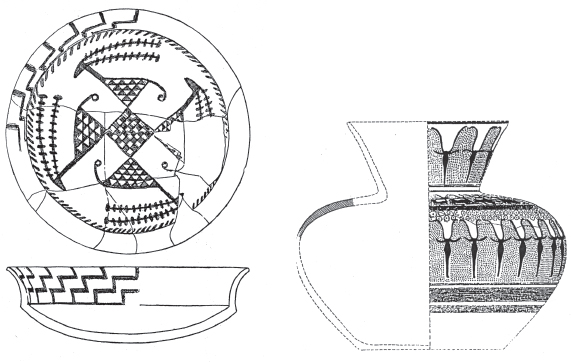

3.4. Painted ceramic containers of the Late Neolithic period with animal ornament, from Samarra (Iraq, seventh millennium BC; after E. Herzfeld. 1930. Die vorgeschichtlichen Töpfereien von Samarra. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer Verlag, fig. 23) and Tell Halaf (Syria, sixth millennium BC; after M. F. von Oppenheim. 1943. Tell Halaf. Erster Band: die prähistorischen Funde. Berlin: de Gruyter, pl. 6.2; figures not to scale).

The observation gains in interest as we broaden our horizons to neighboring regions, and to later periods of Near Eastern prehistory. Where cross-site regularities do exist in the subject matter of pictorial representation, they relate to recognizable types of wild fauna (felines, serpents, boar, and cattle), while the miniature clay figurines recovered from many sites show mainly horned ungulates and human forms, readily distinguishable from one another in the majority of cases.27 Other popular subjects include carnivorous scavengers, perhaps reflecting their role in the ritual removal of flesh from human and animal corpses, prior to revivification with clay and other substances.28 On the eastern mound of Çatalhöyük (ca. 7500–6000 BC), in the Konya Plain of central Turkey, there is evidence that crane wings were worn by human actors in ritual performances,29 but compelling images of composite beings have proved difficult to identify among the site’s uniquely rich corpus of mobile and parietal art.30

Surviving evidence for the development of pictorial art in the later Neolithic of the Near East focuses on the ornamentation of handmade serving vessels. In the seventh and sixth millennia BC, household ceramics became a preferred medium for the execution of painted designs that followed common templates across extensive networks of village societies, spanning impressive geographical distances. Right across the monochrome and polychrome traditions of these periods, painters appear to have favored the depiction of natural kinds of animal and floral subjects, especially those with obvious symmetrical properties that harmonized with the forms of vessels, themselves inspired by the structural properties of basketry (figure 3.4).31 Similar observations can be made for the painted pottery traditions of neighboring Iran during the sixth and fifth millennia BC.32 Composites are also hard to detect among the late Neolithic corpora of clay and stone figurines from northern Mesopotamia, which comprise either animal or human subjects, the latter depicted with widely varying degrees of schematization, and sometimes with added elements of costume or body ornamentation.33

Farther west, a rich and distinctive corpus of late prehistoric (or “predynastic”) art, dating to the early and middle parts of the fourth millennium (ca. 4000–3300 BC), is preserved from the Nile Valley. It focuses to a greater extent upon the ornamentation of cosmetic implements such as ivory combs and palettes for the grinding of body paint (figure 3.5)—legacies from the more mobile Neolithic societies of this region, where farming economies centered initially upon herding rather than raising crops.34 In bringing this chapter to a close I will consider the development of this predynastic art, focusing on changing methods of animal depiction and their relationship to anatomical knowledge in pictorial and nonpictorial domains. This forms a prelude to chapter 4, where I discuss the transformation of Egyptian visual culture during the period of state formation, including the introduction of composite figures, both local and externally derived.

3.5. Predynastic Egyptian cosmetic articles with animal ornament, early to mid-fourth millennium BC: (a, b) bone combs from Naqada, Upper Egypt; (c) fish-shaped siltstone palette for grinding cosmetics from Tell el-Amarna (after J. C. Payne. 1993. Catalogue of the Predynastic Egyptian Collection in the Ashmolean Museum. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press, figs. 75: 1839 and 77: 1904–1905; courtesy Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford; figures not to scale).

AN ART OF AFFINITY: RELATIONALITY IN PREDYNASTIC EGYPT

In Egypt, as elsewhere, prehistoric societies existed in close proximity to the animal world. Detailed observation of animal behavior was integral to the successful pursuit of a hunter-gatherer lifestyle, evidence for which can be traced back into the deep Paleolithic record of North East Africa.35 So too was the effective butchering of carcasses and the use of animal skins, bone, teeth and other body parts for a variety of practical and ritual purposes. Hunting remained an important activity following the widespread adoption of domestic animals in the fifth millennium BC, and later that of cereal farming in the fourth.36 Focused attention on animal anatomy is also evident in the prehistoric funerary record. Burials of animals, both wild and domestic, are attested in Neolithic cemeteries throughout the Nile Valley, and preservative treatments were applied to animal (as well as human) corpses by no later than the mid-fourth millennium BC.37

At Hierakonpolis, in the south of the country, there is evidence for the curation and sacrifice of wild animals in contexts of ceremonial display. Set back from the floodplain of the Nile on the fringes of a large wadi, a remarkable concentration of animal burials, dating to the early and middle parts of the fourth millennium, was established around a complex of human interments partitioned by fenced enclosures.38 They included specimens of elephant, aurochs, hippopotamus, hartebeest, baboon, dog, and wild cats.39 Many of these species must have been brought from distant locations. Another strikingly diverse assemblage of aquatic fauna (turtle, crocodile, and perch of exceptional size) together with wild mammals (Barbary sheep, hare, gazelle) derives from a further enclosure located closer to the floodplain, within the nearby settlement.40

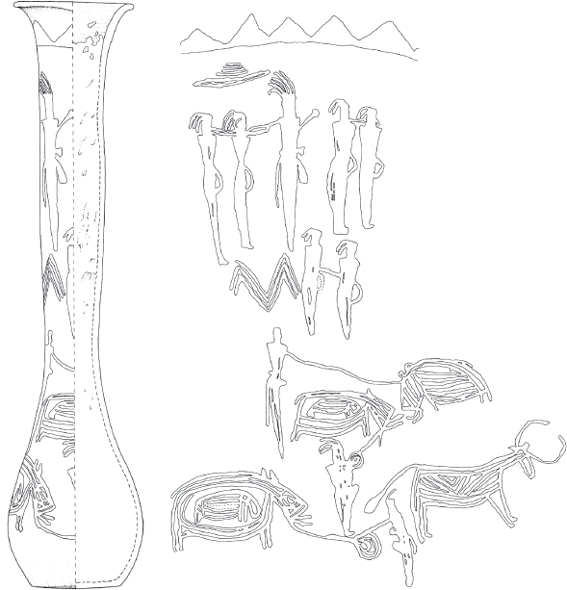

Archaeological evidence of this sort has a bearing on our understanding of contemporaneous imagery, in which animals feature prominently. It demonstrates beyond doubt that predynastic societies in Egypt cultivated intimate firsthand knowledge, not just of the species they kept as domesticates, but also of an extraordinary range of wild fauna distributed across the Nile Valley and the adjacent deserts. In addition to freestanding figurines, media on which animals (and a range of other subjects) were depicted included painted ceramics and a variety of portable, cosmetic articles such as stone palettes for the grinding of pigment and combs, pins, or spoons made of bone or ivory (see figure 3.5).41 A painted vase (figure 3.6), one of two found within a human burial at Abydos in southern Egypt, serves to introduce the predynastic mode of depiction for living kinds.42 It belongs to a class of red-polished ceramics, decorated in white with linear designs, that were regularly produced between around 4000 and 3650 BC.43 The painters of such vessels, which also included bowls and beakers, usually filled the bodies of animals with linear patterns such as radiating triangles, diamonds, or cross-hatching, and on any given container those patterns varied consistently between species. On the taller Abydos vase, the depiction of baby hippo in the bellies of larger ones suggests a concern with what is inside animals, and therefore invisible, which may be relevant to an understanding of nonfigural body patterning as well.

3.6. Tall vase with painted decoration (white on red burnish), from a burial at Abydos, Umm el-Qaab, Upper Egypt, early fourth millennium BC (Naqada I period; after Dreyer et al. 2003; courtesy F. Arnold, DAI Cairo).

Relationships between the internal contents of figures and the wider “landscape” in which they appear are also suggested by the extension of filling patterns and motifs from animal bodies to surrounding parts of the container.44 Human forms, by contrast, are often painted almost solid. Scale and outline provide the only axes of differentiation among them. Their relationships to one another, and also to animals, are indicated by schematic lines, which may or may not represent real objects such as limbs or ropes.45 On a later type of painted pottery, produced between ca. 3650–3300 BC,46 solid color—now painted dark on a pale, marl ceramic—was often used to fill the bodies of both humans and animals completely. As on the earlier painted pottery, elements of costume and the objects carried by humans appear as further extensions of an overall body-shape.47

Despite this lack of emphasis on anatomical detail, animal figures on predynastic pottery of both painted varieties take generally realistic and identifiable forms. Clear and bold outlines allow them to be identified as species existing on the Nile floodplain or in the surrounding low deserts. Contemporaneous images on other media, such as palettes and combs, can for the most part be similarly identified as turtles, birds, fish, hippopotami, horned mammals, and so on.48 In certain cases, however, a play on visual resemblances seems calculated to elicit more than one possible identification, or to avoid definitive identification altogether. A widely distributed type of pendant—found mainly in infant burials—can thus be equally well identified with a bull, ram, or elephant head (figure 3.7a).49 Similar ambiguities surround the interpretation of certain animal designs on cosmetic implements. Combs, pins, and grinding palettes are often topped with symmetrical extensions that have been variously identified as horns or opposed bird-heads (figure 3.7b).50 Some anthropomorphic figurines have beak-like faces, and a striking group from el-Ma‘amariya includes figures with arms raised in a posture that might be identified with curving horns or outstretched wings (figure 3.7c).51

3.7. Ambiguous forms in predynastic Egyptian art, early fourth millennium BC: (a) ivory pendant and (b) bone comb from burials at Naqada (after Payne 1993; figures courtesy Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford), and (c) clay figurine from el-Ma‘amariya (courtesy J. Hubert; figures not to scale).

Insofar as these latter images combine aspects of different body forms, it is in a manner clearly distinct from the composite figures that we find associated with gods and demons in later dynastic art, and whose beginnings I will discuss in the chapter that follows. The earlier, predynastic hybrids do not result from a systematic division and recombination of standardized body parts. Instead they seem to arise from a thoughtful play on continuities and resemblances in the appearance of various species, resulting in a mode of depiction that continues to resist modern attempts at classification. They belong not to the urbanized image world of the composite figure, where we will shortly arrive, but to an earlier art of ambiguity where the forms of living beings mingle and interpenetrate on contact, and where meaningful relations emerge from the blending of affinities rather than from the assemblage of contrasts.