URBAN CREATIONS

THE CULTURAL ECOLOGY OF COMPOSITE ANIMALS

In chapter 1, I retraced Mikhail Rostovtzeff’s search for the origins of “animal style” art in the ancient Old World. There he drew attention to the distinctive pattern-forming behavior of composite figures in the visual record. Despite appearing to be acts of free association, imaginary beings of this type turn out to share formal characteristics that recur frequently and consistently between societies. In the course of the Bronze and Iron Ages, they achieved impressive distributions that extend widely across cultural and political boundaries: a case of cultural resilience against apparently surprising odds (see the following, and chapters 5 and 6).

To explain the peculiar resilience and “catchiness” of composite animals, I laid out, in chapter 2, a preliminary hypothesis based on the principles of evolutionary psychology, and in particular the “epidemiology of culture.” I explored ways in which existing models of that sort might be extended from the analysis of language to images. In particular, I considered how—by targeting our intuitive faculties for the perception of living kinds, but also introducing a breach of expectations—images of composite animals might approximate the cognitive effects of “minimally counterintuitive” propositions, of a kind widely discussed in the evolutionary psychology of religion. Provided the correct balance is achieved, and the ratio of real to unreal elements does not tip too far either way, an epidemiological model would attribute to such images certain selective advantages, accounting for their ability to become “both relatively stable within a group and recurrent among different groups.”1

The patchiness of composites in the prehistoric visual record, which I discussed in the preceding chapter, has already posed difficulties for this hypothesis. It is beyond doubt that Paleolithic and Neolithic societies sometimes created durable images of composite beings, and the few surviving candidates have often been accorded great prominence in modern interpretations. Yet they remain strikingly isolated. If the popularity of minimally counterintuitive images is to be explained by their core cultural content and its appeal to universal cognitive biases, then why did composite figures fail so spectacularly to “catch on” across the many millennia of innovation in visual culture that precede the onset of urban life? Much hinges here upon our conceptualization of the “counterintuitive” and its role in cultural transmission, a problem that I will return to in later chapters. A more immediate priority is to establish the point at which such figures do achieve some wider currency, and begin to behave in the kind of culturally contagious ways that Rostovtzeff would have recognized for later antiquity. To what kind of “cultural ecology”2 does the composite animal belong? In answering this question, I will begin where the previous chapter left off, in Egypt.

FITNESS OR “FITTINGNESS”? COMPOSITES IN EARLY DYNASTIC EGYPT

It has long been recognized that the emergence of a unified territorial state in Egypt, between around 3300 and 3000 BC, was accompanied by marked transformations in visual culture.3 The change is most apparent in the development of images that were carved in raised relief on ceremonial objects of the period. Such objects, which include weapons and items of personal display, express the self-fashioning practices of ascendant elites.4 Dense arrangements of figures emerge directly from their surfaces, like magnified versions of the raised impressions produced by cylinder seals. The latter were introduced to Egypt from western Asia around the middle of the fourth millennium BC5 as a novel way of marking the clay closures of commodity vessels, including vessels deposited as offerings in high status tombs. At that time, competing chiefdoms reached out to obtain novel sources of distinction and prestige, forming new frontiers of exchange around the Levantine coast and the shores of the Arabian Peninsula.6

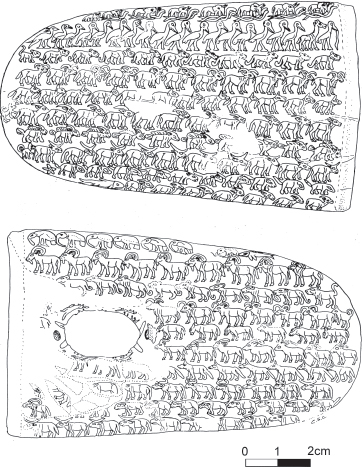

4.1. The “Two Dog Palette” from Hierakonpolis, Upper Egypt, ca. 3200 BC (courtesy Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford; drawing by Marion Cox).

Periods of intensified exposure to outside influence are often also times of extraordinary cultural efflorescence and innovation, combined with aggressive competition over traditional sources of value. In Egypt, investment in new modes of depiction focused initially upon established status symbols and media of personal presentation. Cosmetic grinding palettes, combs, knives, and mace-heads—central components of social display in the Nile Valley since Neolithic times—were now decorated with relief figures of wild and dangerous animals (figure 4.1).7 Both in technical execution and principles of composition, these sculpted bodies mark a departure from the animal imagery of predynastic times, discussed in chapter 3. Together with the novel play on light and shadow produced by relief carving, there is a completely new emphasis on details of joints and musculature. Once the outline of a figure had been established, incision and fine modeling were used to distinguish not only individual body parts but also particular structural features and elements that correspond to an empirical reality below the skin. In some cases, the repetitive carving of these lifelike creations in row after minute row suggests an aesthetic interest in the standardization of form (figure 4.2). The Egyptian (dynastic) artist, as Kent Weeks suggests: “was a keen observer of nature and, even in the earliest reliefs he exhibited an awareness of the subtleties of musculature and surface anatomy to the point that some of his relief figures look like illustrations from an early medical textbook.”8

These observations should, however, be set against the pervasive unreality of protodynastic Egyptian art. The same anatomical empiricism that allows these animal depictions to be identified with zoological precision9 also produced an entirely new kind of visual imaginary, based on the subdivision of accurately rendered body parts and their reassembly into ostentatiously artificial wholes. It is as though the entire field of image making were being reinvented on the basis of a new theory of material connections and integration; a new understanding of part–whole relations, of which composite animals—which now included both homegrown and imported varieties10—are just one, especially clear manifestation. The same applies, broadly, to dynastic modes of depiction for the human form, the core principles of which remained relatively stable from the First Dynasty onward. Bodies were constructed out of standardized parts, each depicted with great precision in its typical form and assembled in the manner of a “composite diagram.”11 Anatomical elements were treated almost as discrete entities, unified within the confines of an encompassing outline. Their dimensions adhered broadly, but not rigidly, to an ideal system of proportions, compatible with more general principles of Egyptian metrology.12

4.2. Ivory handle of a ceremonial flint knife found at Abu Zaidan, Upper Egypt, ca. 3300 BC (after Needler 1984; drawings by C. S. Churcher; courtesy Brooklyn Museum, Museum Collection Fund, New York).

This modular logic of depiction provided a powerful template for integrating art and writing, and for the close translation of forms between two- and three-dimensional surfaces.13 Phonetic or ideographic signs could thus be mounted on legs, endowed with arms, or enclosed within architectural motifs to enhance their meaning within a composition (figure 4.3a). “Composite hieroglyphs” of this kind are attested in a variety of forms by the First Dynasty, and may have been initially developed for the writing of royal names.14 They were integral to the formation of the dynastic representational system as a whole. Statuary, and in particular the cult statues of gods, is likely to have formed the core of that system, providing models for royal and elite display.15 Two-dimensional and relief representations of divine agency, which survive in greater numbers, include (but are not confined to) figures that fuse an idealized human body with an animal head. Composites of the latter sort were not depictions of gods. Rather they extended the visual logic of the hieroglyphic system to beings whose true physicality was unknown, and who could therefore be approached only through allusions to their supposed qualities and functions.16 A host of “demonic” agents, both benevolent and harmful, were also approached through images of composite bodies, depicted on magically protective instruments and texts (figure 4.3b).17

Intriguingly, the adoption of composite principles in Egyptian art was accompanied by analogous developments in a range of other technological domains, especially those associated with the activities of the early dynastic court (ca. 3100–2800 BC), attested mainly in the material remains of elaborate funerary rituals. Modular construction techniques can be detected in both miniature and monumental formats, and in such diverse products as decorated boxes of wood and ivory,18 boats made with exotic timber,19 and perhaps also in the mud-brick echoes of a now-vanished tradition of ceremonial architecture, in which wooden buildings played a central role.20

4.3. (a) Composite hieroglyphs of the First and Second Dynasties (ca. 3100–2650 BC; after Fischer 1978); (b) ivory birthing tusk with protective images and inscription, from Thebes, Upper Egypt, ca. 1800 BC (after W.M.F. Petrie. 1927. Objects of Daily Use. Cairo: The British School of Archaeology in Egypt, pl. 37: f–g).

4.4. Composite construction in Early Dynastic Egypt: (a) ivory furniture support in the form of a prisoner, with dowel for attachment, from Hierakonpolis, Upper Egypt (after J. E. Quibell and F. W. Green. 1900. Hierakonpolis I. London: B. Quaritch, pl. 11: 4–6); (b) construction of a bed frame with bull’s leg supports from Saqqara, Lower Egypt, late fourth to early third millennium BC (after Emery 1961, fig. 130; image courtesy of the Egypt Exploration Society).

Mortise-and-tenon joints became a standard method for assembling complex structures out of prefabricated and uniform elements, replacing or supplementing earlier techniques of lashing and binding.21 In the remains of high-status furniture, which became a focus of craft specialization,22 these technological changes come together with the world of images depicted on ceremonial objects. Some hundreds of ivory furniture attachments fitted with dowels and slots have been recovered, and can sometimes be identified as three-dimensional versions of figures carved in relief on palettes, knives, and maces, pointing toward the creation of a unified visual environment for elite culture (figure 4.4a).23

Like the wooden or ivory bull hooves carved in standard sizes and attached to the legs of carrying beds and chairs (figure 4.4b),24 images of composite beings slotted neatly into this new material and conceptual world. Their appearance in Egypt—which included the adoption of Mesopotamian prototypes, discussed in the next section—might then appear to have little to do with adaptive “fitness,” in the sense of evolved cognitive biases that might favor their reception, and more to do with what Ian Hodder calls a kind of “fittingness.”25 Albeit in a strangely inverted fashion, composites imply within their own structures certain principles of integration that were weakly developed in prehistoric societies, becoming prominent only with the emergence of urban life, and thus helping to account for the flow of images between urban contexts. This is of course a large generalization to make from a single case. In putting it to the test, a broader range of examples is needed.

THE BRONZE AGE: SETTING A SCENE

To set the scene, it is useful to summarize the more commonly recognized features of Bronze Age civilization in the Near East and neighboring regions, those that differentiate it from earlier, Neolithic civilizations. In terms of social structure, the most important are urbanization, the centralization of political and ritual institutions, and the specialization of crafts dealing both in material things and immaterial knowledge, including—in some cases—the invention of the earliest known writing systems.26 These organizational changes were typically preceded by the expansion of commercial networks using new transport technologies (pack animals, wheeled carts, and sailing ships) as well as rationalized forms of commodity production and packaging that accelerated the pace of commerce. They were locally sustained through the intensification of agriculture, using animal traction and irrigation. Only three types of Old World environment could support the combined effects of these processes—albeit at widely varying scales—and all were periodically subject to overexploitation, leading to decline. These were the seasonally refreshed floodplains of major rivers, the rain-fed steppes where farming could be practiced without irrigation, and the more circumscribed valley systems and oases watered mainly by runoff from adjacent highlands.27

As Rostovtzeff was already able to perceive, the frequency with which urban life took root in such areas, and its subsequent rhythms of expansion and contraction, were closely related to shifting networks of trade (figure 4.5). Long-range commerce centered on a restricted range of commodities—notably metals—whose natural distribution lay, not within the centers of population growth, but along their highland interstices.28 The transformation is first evident during the late fourth millennium BC, on the banks of the Tigris and Euphrates and in the valley and delta of the Nile, where newly formed polities drew in material resources from an extensive hinterland, reaching from the gold mines of the Nubian Desert to the lapis sources of Afghanistan.29 In the early centuries of the third millennium, a new frontier of urbanization opened out along the land routes between lowland Mesopotamia and Afghanistan, crossing the copper-rich uplands of the Iranian Plateau.30

By 2500 BC, the expansion of maritime trade between Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley had stimulated further cycles of urban growth around the fringes of the Persian Gulf,31 and the process was echoed to the north, on the Syrian steppe, where caravan routes now converged on the kingdom of Ebla.32 The cities of the Punjab in turn forged new connections across the Iranian Plateau, extending toward the inland river deltas of Central Asia.33 There, facing the black sands of the Karakum and Kyzylkum, a distinct form of urban life took root in the final centuries of the third millennium.34 And at much the same time, a new zone of maritime interaction was opening up along the Eastern Mediterranean seaboard, with momentous consequences for the island of Crete, and its European hinterland.35

4.5. From the Indus to the Aegean: selected Bronze Age sites and interregional trade routes, ca. 2500–1800 BC.

Each of the areas affected conferred its own cultural foundations upon the basic elements of urban civilization, abandoning certain features of its prehistoric past, but retaining and elaborating others—a role of custodianship usually taken by emergent elites. So, while all share a certain “family resemblance,” there are also pronounced differences between them, which arise from their distinct social structures and ecological settings. The differences are clearly evident in styles of urban planning, in settlement forms and patterns, in cosmology and related modes of ceremonial practice, and in the presence or absence of significant institutions, such as literate bureaucracies and sacred kingship.

CIVILIZATION: A MONSTROUS DAWN

It is striking that, in spite of the differences between them, none of the regions I have mentioned adopted the core features of urban civilization without also establishing a visual repertory of fantastic, composite creatures. In some cases, composite animals were initially introduced from neighboring or more distant centers, passing along the same routes of transmission that brought metals, precious stones, and other commodities deployed locally in the legitimization of elite status. An important factor in their dissemination was the use of carved seals to roll or impress complex images onto the clay closures of transport containers, about which there will be more to say in the following chapters.

Such was almost certainly the case with the appearance in protodynastic Egypt of serpent-necked felines and griffins—both of Mesopotamian or western Iranian origin—during the late fourth millennium BC.36 Upon arrival, these imported composites, which had only recently made their debut on the floodplains of the Tigris and Euphrates, were accorded a central place in the emerging ideology of sacred kingship.37 On the obverse of the Narmer Palette, an early royal monument, their intertwined necks—now leashed by human keepers in what appears to be a local modification—are ingeniously adapted from the miniature medium of seal carving to form a protective rim around the grinding area, where ritual substances were processed before being ingested or applied to the body (figure 4.6).38

4.6. (a) Serpent-necked felines carved in relief on the central register of the Narmer Palette, from Hierakonpolis, Upper Egypt, and (b) similar figures on cylinder seal impressions from Uruk in southern Mesopotamia, late fourth millennium BC (after Wengrow 2006, figs. 2.1–2.2; Frankfort 1939, pl. 4: d, f).

The composite figure of the goddess Taweret, closely associated with the protection of women in childbirth in her area of origin, underwent a similarly impressive transposition.39 Toward the end of the third millennium (ca. 2300–1900 BC), she leapfrogged from the banks of the Nile to the maritime cities of the Levantine coast, and thence to protopalatial Crete.40 On arrival, she picked up a mixture of Aegean and perhaps also Anatolian features,41 paving the way for a series of further monstrous migrations from the east, including the sphinx and griffin, whose watchful eyes overlooked the rebirth of the Minoan palaces in the later Bronze Age (ca. 1700–1400 BC).42 The same three composites—sphinx, griffin, and Taweret in her Minoan form—also traveled farther westward, blending seamlessly into the martial culture of the Greek mainland, and taking up privileged places of residence in the newly constructed palaces at Mycenae, Pylos, and Tiryns (see chapter 6, figure 6.1).43

4.7. Carved intaglio seals from (a) Pakistan (Mohenjo-daro); (b) Bahrain (Karrana); and (c) Turkmenistan (Gonur South), late third to early second millennium BC (after J. P. Joshi and A. Parpola, eds. 1987. Corpus of Indus Seals and Inscriptions, Volume 1, Collections in India. Helsinki: Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia, fig. M-302, original photograph by Erja Lahdenperä, courtesy Archaeological Survey of India; K. M. Al-Sindi. 1999. Dilmun Seals. Bahrain: Bahrain National Museum, pp. 325–326, no. 249; F. Hiebert. 1994. Origins of the Bronze Age Oasis Civilization in Central Asia. Cambridge, MA: American School of Prehistoric Research, Bulletin 42, p. 151, fig. 9.14: 3).

Each of the urban centers that arose earlier in South and Central Asia, during the third millennium BC, cultivated its own brood of composite animals. We do not know their names, but they are clearly recognizable among the regional styles of glyptic imagery produced in the Indus Valley44 and the Persian Gulf,45 and subsequently in Bactria and Margiana (figure 4.7).46 The stone or metal seals on which they were executed were highly durable objects, and occasionally moved over great distances, together with the commodities they marked.47 The Iranian Plateau and the Syrian steppe have their own, slightly different tales to tell. In the former area, the knitting together of highland and lowland societies into a larger “Proto-Elamite” culture zone was accompanied by the creation of a new repertory of visual symbols, including wild animals performing human activities such as writing, plowing fields, traveling by boat, fighting with weapons, and bearing offerings (figure 4.8a).48 As in Mesopotamia, these designs—carried on cylinder seals—were impressed onto the mud closures of commodity vessels, and onto the surfaces of administrative documents and clay door locks, as well as being transposed to larger media.49 True composites, such as the griffin, also appear in the glyptic art of the Proto-Elamite expansion (figure 4.8b), but overall it was the actions performed by animals—rather than their anatomical forms—that sustained this particular construction of the unreal.50

Urban civilization took root on the grassy steppe of inland Syria at the beginning of the fourth millennium BC and intensified toward its end. Southern Mesopotamian influence along the Middle Euphrates is apparent in (among other things) the adoption of cylinder seals bearing images of composites, including types that were transmitted concurrently to Egypt.51 Around 3100 BC, both Syria and much of northern Mesopotamia witnessed a marked contraction of urban life and long-range commerce. Seals continued in use, and were once again employed in conjunction with painted pottery. Composite animals, however, had no apparent role to play in these more localized forms of cultural display, which spread across the Taurus and Zagros piedmont through social networks comparable in scale to those of Neolithic times.52 Equally notable is their spectacular reappearance, both in seal imagery and in larger media, during the mid-third millennium BC. Sometimes termed Syria’s “second urban revolution,” this period saw the reestablishment of long-range commercial ties between the steppe zone and the city-states of the southern Mesopotamian alluvium.53 Once again, the latter region provided a readymade repertory of composite figures—now heraldically posed in scenes of combat with human heroes—that was adopted with various modifications by Syrian seal-carvers, and transposed onto more monumental media of display (figure 4.8c).54

4.8. (a, b) Cylinder seal impressions from Tall-i Malyan, Fars, southwestern Iran, early third millennium BC (Proto-Elamite; after Pittman 1997: 156, figs. 4c, d), and (c) from Royal Palace G at Ebla, Syria, mid- to late third millennium BC (after Porada 1985: 92, fig. 14).

A general relationship has emerged between the spread of urban life and the widespread transmission of images depicting composite beings. To an extent, that is perhaps alarming—these distributions are often traceable through just a single, surviving medium: image-bearing seals made of durable materials and their impressions on a variety of malleable surfaces, ranging from the mud stoppers of commodity jars to the strips of clay placed across door-thresholds to deter entry, and—in the cases of Mesopotamia and western Iran—the surfaces of clay documents used to record transactions. Undoubtedly, seals are best regarded as tracers for a wider range of commodities, most of which are not preserved in the archaeological record. Among the latter, dyed and ornamented textiles—the quintessential value-added products of early urban economies—are likely to have played a significant role in the long-range dissemination of visual styles and motifs.55 In view of these preservation biases, we might be wary of attaching too much significance either to the seals themselves or to the objects they marked. As the earliest known device for mechanically reproducing a complex image, the impact of seal use on the transmission of visual designs nevertheless warrants closer investigation. I will return to this issue in the chapter that follows.

A WORLD DIVIDED: COMPOSITES, COMMODITIES, AND THE URBAN MILIEU

To further define the cultural ecology of the composite animal, I will focus on the initial transition from village to urban life in Mesopotamia. Through their expansive commercial interests, the first cities established along the Tigris and Euphrates rivers provided a stimulus and example for the growth of centers elsewhere. While the institutional foundations of early urban society there remain poorly understood, the Mesopotamian case therefore retains a certain primal status for the wider urban milieu of the western Old World.

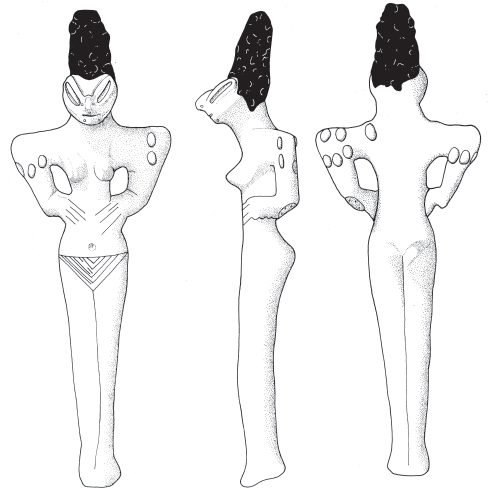

4.9. Composite figurine with female attributes, from a grave at Ur/Tell el-Muqayyar, southern Mesopotamia, fifth millennium BC (‘Ubaid period) (after McAdam 2003: 165, fig. 1).

Two closely related features of that transition are especially germane to the development of composites: the overall standardization of material culture and the cultivation of new technologies based on modular principles of assembly. The beginnings of these processes lie in small-scale communities scattered across the plains of central and northern Mesopotamia, and in neighboring parts of southern Turkey (ca. 5000–4300 BC). These village societies already display emergent properties of urban life that differentiate them from their Neolithic antecedents.56 Their ceramic repertories exhibit a new degree of uniformity and an overall reduction of aesthetic investment,57 and the figurines of this period—which unite elements of human and reptilian form—include complex and relatively standardized forms made by “adding body parts to a central stalk, with features created by carving, painting or application” (figure 4.9).58

The use of stone seals to mark the clay closures of commodities was already widely established in Mesopotamia by the fifth millennium BC, but it was only in this phase of village life that their surface designs began to feature an increasingly diverse range of figural images, often depicted with detailed rendering of joints and musculature.59 The spatial distribution of those images, preserved mainly as impressions on vessel sealings, follows a dense network of highland–lowland trade that extended along the flanks of the Zagros and Taurus mountains, and onto the neighboring plains.60 In addition to horned animals and humans, creatures with multiple limbs make their first appearance, as does a widely distributed but as yet only loosely standardized image of a human body topped by a goat’s head or mask, holding aloft snakes or other dangerous animals (figure 4.10).61

With the expansion of urban settlements throughout Mesopotamia during the fourth millennium BC, the trajectory toward standardization and modularity in material culture intensified markedly. Systems of modular construction, based on the assembly of standardized and interchangeable components, are evident not just in imagery at this time, but also across such diverse technological domains as mud-brick architecture and ceramic commodity packaging (figure 4.11).62 These wider developments in material culture underpinned the invention, around 3300 BC, of the protocuneiform script.63 This new system of information storage was initially designed for bookkeeping purposes in large urban institutions, which acted as the religious and economic hubs of the earliest cities. It was based on a principle of differentiation whereby materials, animals, plants, and labor were divided into fixed subclasses and units of measurement, organized according to abstract criteria of number, order, and rank. Many of the earliest known administrative tablets thus functioned in a manner comparable to modern punch cards and balance sheets. In order for such a recording system to function, every named commodity—each beer or oil jar, each dairy vessel, and their contents, and each animal of the herd—had to be interchangeable with, and thus equivalent to, every other of the same administrative class.64 A smaller number of early inscriptions, known as lexical lists, appear to have had no direct administrative function, and may reflect the intellectual milieu of the earliest scribes, who engaged, as part of their training, in “fanciful paradigmatic name-generating exercises” for a wide range of subjects.65

4.10. Illustration of sealing mechanism and examples of images impressed with stamp seals onto the clay sealings of storage vessels, Mesopotamia and western Iran, late fifth to early fourth millennium BC (after Frankfort 1939, p. 2, fig. 1; Amiet 1980, pls. 2, 6, 7).

4.11. Pouring vessel showing composite construction, from Habuba Kabira South on the Syrian Euphrates, early urban/Uruk period (late fourth millennium BC) (after D. Sürenhagen. 1978. Keramikproduktion in Habuba Kabira-Süd. Berlin: Bruno Hessling, fig. 49).

The invention of a novel repertory of composite figures can be seen to “fit” very logically into this urban and bureaucratic milieu. In pictorial art, new standards of anatomical precision and uniformity, evident in both miniature and monumental formats, echoed wider developments in material culture.66 Through the medium of sealing practices, miniature depiction remained closely tied to the practice of administration, which required the multiplication of standardized and clearly distinguishable signs for the official marking of commodities and documents. Variability among seal designs was generated through often-tiny adjustments in the appearance or arrangement of figures and motifs. These did not alter the overall visual statement, but allowed each design to fulfill its designated role as a discrete identifier within the larger administrative system to which it belonged.67

In its search for new subject matter, it is hardly surprising that the “bureaucratic eye” was increasingly drawn to the possibilities of composite figuration (figure 4.12). Not only did a composite approach to the rendering of organic forms greatly multiply the range of possible subjects for depiction. As Barbara Stafford points out, the counterfactual images that it produced also serve to emphasize details of anatomy that would normally “slip by our attention or be absorbed unthinkingly,”68 becoming noticeable only when disaggregated from their ordinary contexts. Composites thus encapsulated, in striking visual forms, the bureaucratic imperative to confront the world, not as we ordinarily encounter it—made up of unique and sentient totalities—but as an imaginary realm made up of divisible subjects, each comprising a multitude of fissionable, commensurable, and recombinable parts.

4.12. Cylinder seal impressions showing experiments with composite figuration, from Mesopotamia and western Iran, late fourth millennium BC (after R. M. Boehmer. 1999. Uruk: früheste Siegelabrollungen. Mainz am Rhein: Philipp Von Zabern).