MODES OF IMAGE TRANSFER

TRANSFORMATIVE, INTEGRATIVE, PROTECTIVE

The interaction of mental images and physical images is a field still largely unexplored, one that concerns the politics of images no less than the imaginaire of a given society.

—Hans Belting, Image, Medium, Body, 2005: 304

The distribution of composite figures in the visual record raises a number of intriguing problems for the study of cultural transmission, for which only partial and unsatisfactory solutions have so far been offered. Their impressive transmission across cultural boundaries, to be analyzed further in this chapter, is consistent with the expectations of an “epidemiological” approach to the spread of culture, which would accord them a special kind of cognitive catchiness. But that approach, in its current form, offers no way of explaining why such images become stable and widespread only with the onset of urban life and state formation, beginning little more than six thousand years ago—a mere blink of the eye, on the timescale of biological evolution. In the western Old World, high levels of covariation occur between figures of this type and mechanical modes of image making, but, for reasons explored in the previous chapter, a direct causal relationship between the two phenomena can be safely ruled out.

More promising avenues of enquiry were opened up in chapter 4. It was argued there that composite figures “fit” within the wider cultural milieu of the earliest cities, where principles of modular construction and reasoning were cultivated for a wide range of activities such as commerce, administration, and display. But this does not explain the recurrence of the same imaginary figures in different cultural settings. In this chapter, I address the latter problem, focusing on the institutional role of externally derived images within centralized (or centralizing) societies. I will suggest that the macro-distribution of composites follows two distinct but regular modes of transmission and reception, to be termed “transformative” and “integrative.” The fact that both modes can be exemplified from more than one region and chronological period provides a measure of confidence that the patterns observed, while contingent on particular sets of institutional conditions, are not simply random.1

I will then go on to introduce a third mode of transmission, which I term “protective.” Attested most clearly in written and pictorial sources of the first millennium BC, it is defined by the magical deployment of images as defense against the spread of illness and misfortune: an epidemiology of representations, yes, but of a more literal kind than envisaged by evolutionary psychology. These three modes do not exhaust the range of processes through which images of composite beings were transmitted among Bronze and Iron Age societies. Closer inspection of written and pictorial evidence from any single region or period would undoubtedly reveal others. Nor are they mutually exclusive. They shade into one another at various points, and the contrasts between them, which often emerge from very different kinds of source material, should not be overstated. I will begin with transformative modes, where the reception of composite figures from an outside source is associated with periods of accelerated structural change in the host society.

TRANSFORMATIVE MODE: COMPOSITES INTRUDE

Transformative modes of image transfer belong to a wider class of what Andrew Bevan calls “contact phenomena,” appearing among communities that were being strongly influenced by external factors, “sometimes attractive, sometimes repellent.”2 Perhaps the most intensely investigated example is that of Iron Age Greece in a period of city-state formation, commercial expansion, and colonization.3 As Robin Osborne writes of Archaic Greek art:

The animals of the eighth century are predominantly domestic, those of the seventh century fantastic. Creatures of the imagination colonize pots and dedications alike. Not only do fantastic creatures appear in scenes that show stories, but all sorts of parts of vessels of clay, metal, wood, and stone turn into animals’ bodies. From the late eighth century molded snakes writhe their way around the shoulders of Athenian Late Geometric amphorae, and the tripod cauldrons, prestigious dedications at major sanctuaries, sprout griffins’ heads.4

What Osborne captures so effectively is the intrusion of composites—all of them imported from eastern sources—into the heart of an existing cultural milieu.5 The wider transformation of that milieu between the seventh and sixth centuries BC has been characterized as one in which architecture changed “from mud-brick huts with reed roofs and rough stone foundations into marble temples with precisely cut blocks and elegant decorative features, sculpture from small, lumpy terracotta figurines into over-life-size statues of marble or bronze, replete with observed detail, and painting from strips of purely linear design into large-scale figure-compositions of considerable refinement.’6

James Whitley provides a valuable discussion of local variability in the Greek reception of foreign composites, highlighting their wider social significance at a time of institutional change on the mainland.7 He focuses on the dispensation of orientalizing ceramics and metalwork in seventh-century Attica, identifying tensions in the consumption of eastern goods and imagery that were specific to that region, but also shed light on processes taking place in other parts of the Aegean. Throughout much of Greece, the seventh century BC was a period of heightened competition between local elites, whose authority was based on personal ties of loyalty, underpinned by kinship obligations and claims to ancestral status.8 Since the commencement of the Iron Age, in the tenth century, this aristocratic ideal had been sanctioned through a restricted set of ritual practices, in which the selective display of exotic trade items signaled the attainment of rank and status. Grave goods at that time show a hierarchical pattern of distribution in the archaeological record, and imagery—of chariots, battle scenes, and arrangements of human and animal figures—was carefully rationed on ceramics, metalwork, and ivories. With the exception of centaurs, which first appear on Late Geometric pottery, composites are absent from the decoration of these and other display media.

Whitley considers how, by the late eighth century—in Corinth, Euboea, and other parts of Greece—this established social order was disrupted and transformed through the arrival in increasing quantities of foreign trade goods and through the emergence of a cosmopolitan elite, membership of which was defined and signaled primarily through the use of non-Greek objects, images, and practices. The incorporation into local idioms of display of foreign (mainly Levantine) visual designs, and their percolation across multiple levels of Greek society, is reflected in the increasing popularity of orientalizing motifs—including a variety of composite animals—on painted and incised ceramics, whose decoration emulates the appearance of more prestigious metalwork (see also chapter 1). For local elites, orientalizing objects were both sought after and potentially threatening, an ambivalence that Whitley finds most strongly expressed in the region of Attica, where he detects an attempt to circumscribe the symbolic potential of foreign trade goods within established codes of ceremonial display.9

An association between composites, introduced from outside sources, and the reformulation and efflorescence of elite culture can be similarly traced for earlier periods of Mediterranean history. In the centuries directly preceding the emergence of their respective palatial civilizations, both protopalatial Crete (ca. 1950–1700 BC) and Late Helladic I–II Greece (ca. 1600–1350 BC) witnessed an influx of such images carried respectively on Egyptian scarabs and on cylinder seals of the “Common Mitanni Style,” and no doubt also on other, less durable media such as textiles and metalwork.10 In each case, we can follow the incorporation of imported composites into an elite cultural milieu, together with a variety of other exotic practices and commodities. Taweret on Crete adopts the role of “libation carrier” and “bearer of offerings,” as though she had been born into the rituals of Minoan palace life (figure 6.1a).11 Likewise, the sphinxes and griffins that arrived on the Greek mainland merged into the newly ordered space of the megaron, where sacrifices were performed before the wanax, and took up prominent roles in the heroic pageant of Mycenaean kingship (figure 6.1b,c).12

Conventional use of the term “orientalizing” to describe such processes is unhelpful. It confines them to a particular spatial and chronological horizon, and to a particular point of view: the Greek or (implicitly) “European” one. It also discourages comparisons with comparable phenomena of cultural fusion and transformation elsewhere. For example, concurrent with her penetration into the Aegean world, Taweret also moved south into Africa, where she was adopted by indigenous elites whose emergent centers of power lay astride the Third Cataract of the Nile, at Kerma.13 There her protective figure appears at the heart of royal rituals, arrayed along the head and foot supports of ceremonial beds—traditional carrying equipment for deceased members of the court en route to their monumental tombs, where both human kin and cattle were sacrificed in spectacular burial rites.14

Further comparisons can be drawn with the much earlier reception of Near Eastern composites in protodynastic Egypt, at the end of the fourth millennium BC, similarly associated with an efflorescence of elite culture and with the coalescence of new institutions—in this case, the unification of the “Two Lands” of Upper and Lower Egypt under a form of sacred kingship that lasted, in its essentials, until the Greco-Roman period. The core ingredients, discussed in chapter 4, are all there, unfolding over a similar time span of three to four centuries: an influx of composite figures from distant sources, carried on expanding routes of long-distance maritime and overland trade; their incorporation into culturally salient objects and practices that were previously free of them; and their deployment by new and powerful groups whose influence transcended that of earlier factions on both the local and supra-local levels.15

6.1. (a) Cretan rendering of Taweret on a stamp seal impression from Phaistos; (b) griffins pulling a chariot on an impression of a gold signet ring from a tholos tomb at Anthia in Messenia, Greece, mid-second millennium BC; and (c) griffin-lion pair on a wall frieze reconstructed from fragments found in the later palace at Pylos, thirteenth century BC (after Weingarten 1991, p. 22, fig. 3; Krzyszkowska 2005, p. 252, fig. 486, photograph of impression by Olga Krzyszkowska; M. Lang. 1969. The Palace of Nestor at Pylos in Western Messenia II: The Frescoes. Princeton, NJ: University of Cincinnati and Princeton University Press, pl. P-21C46, courtesy of the Department of Classics, University of Cincinnati).

I have defined a recurrent mode of cultural transformation, with recognizable archaeological traces and consistent manifestations across multiple regions and periods. As first exemplified in the fourth millennium BC, the pattern is one of disruption and accelerated change—characteristic of the periods labeled “proto-” or “archaic”—in which received cultural categories are brought into question through heightened exposure to foreign influence. The incorporation of composites, originating outside the established boundaries of a given cultural milieu, is a consistent feature of these transformations, from protodynastic Egypt to Archaic Greece. In no instance can any simple causal relationship be posited between institutional change and the adoption of a foreign bestiary in art or ritual. It is notable, however, that in each of the cases described, exotic composites are associated with the material culture of social elites in the process of self-fashioning, and were accorded discursive prominence through their incorporation into important rituals and ceremonies. The cumulative unfolding of this cultural pattern across an ever-widening area created a common fund of fantastic imagery, shared by Bronze Age elites from the Near East to the Aegean. The growth of this common reservoir of images, connecting elite worlds via the otherworldly, was a precondition for my second mode of cultural transmission: the “integrative” mode.

INTEGRATIVE MODE: COMPOSITES MOVE BETWEEN

The transmission of images in the integrative mode corresponds closely to the development of what are often termed “intercultural” or (anachronistically) “international” styles in the art of the ancient Near East and Mediterranean—that is, elite visual styles blending elements of diverse cultural origin, and resisting identification with particular craft centers or “schools.”16 Marian Feldman, in her book Diplomacy by Design, has done much to clarify the distinctive features of intercultural style objects in the later Bronze Age, including the pervasive presence not only of imaginary animals (notably sphinxes and griffins) but also of composite, fantastical plants among their surface decoration. During the fourteenth and thirteenth centuries BC, luxury goods took on common forms across cultural boundaries, working to consolidate otherwise fragile commercial and political bonds through their circulation as gifts and countergifts. At this time of intense interregional diplomacy between the royal courts of the Eastern Mediterranean, imaginary landscapes—ornamenting the highly crafted surfaces of luxury furniture, vessels, and vehicles—reveal, in their distribution, the cosmopolitan face of courtly life—the desire for mutual recognition and integration across often tense cultural boundaries, negotiated amid the ever-present uncertainty of dynastic politics.

International correspondence of the period, preserved mainly from cuneiform archives found in New Kingdom Egypt and Hittite Anatolia, reveals a sharp competitive edge to royal exchange, and indicates the risks of diplomatic failure entailed by inadequate or inappropriate gestures.17 It is within this ostentatious and fissile world that Feldman locates the decoration of “international style” objects. Composite animals typically feature there in scenes of predation where they are incorporated, either as violent opponents or protective allies, with images of real wild animals such as lions (figure 6.2).18 She suggests that both composite creatures and imaginary plants (notably the “stylized voluted palmette”) serve to locate this imagery “outside the realm of the physical world and into ‘otherness’ that could be either threatening or protective.”19 The evidence assembled by Feldman is extremely diverse, and the characteristics of the integrative mode may be easier to define if we consider an earlier example, more tightly focused upon a single medium.

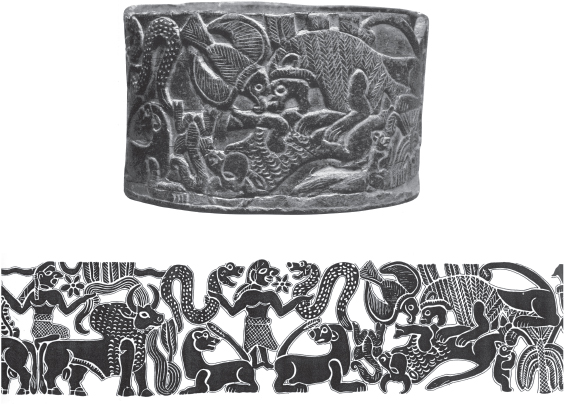

During the middle and later part of the third millennium BC, in the Early Bronze Age, highly ornamented vessels made from a soft, dark stone known as chlorite achieved an extremely wide distribution, reaching from Central Asia to the Euphrates, and passing across a multiplicity of cultural and political boundaries.20 Such vessels are most frequently documented between the central and southern coastlines of the Persian Gulf and the city-states of lowland Mesopotamia and Khuzistan, where they have been found in temples dedicated to various deities. Carved with metal tools, these “intercultural style” containers, as they are known, were highly individualized both in form and decoration.21 Each was densely ornamented from lip to base on its outer surface with varying combinations of patterned relief carving, figural attachments, and inlays of colored stone and shell (figure 6.3). Composite animals figure prominently, most often in the form of lion-headed serpents, but also including standing bull-men.22 They are among those images of living beings whose bodies are animated by paint and colored inlay. Scorpion-men and lion-men, sometimes shown in the “master-of-animals” pose, are known on chlorite vessels recovered in southern Iran, but as yet these have no clear parallels from excavated contexts.23

6.2. Wooden box lid with relief carving of a landscape populated by real and imaginary animals, found at Saqqara in northern Egypt, ca. 1400 BC (after Morgan 1988: 52, fig. 41).

6.3. Soft-stone vessel with intercultural-style ornament from Khafaje, Iraq, mid-third millennium BC, and rolled-out reproduction of its surface decoration (after H. Frankfort. 1954. The Art and Architecture of the Ancient Orient. Harmondsworth: Penguin, p. 19, fig. 9. © The Trustees of the British Museum).

Sources of chlorite were concentrated in central Arabia and around the highland margins of the Gulf of Oman, and production centers for intercultural-style vessels have been identified at Tepe Yahya and perhaps also at Konar Sandal, in the vicinity of Jiroft.24 The location of these sites in the Halil River basin, with ready access to a major maritime outlet at Bandar Abbas, suggests a commercial orientation for the development of intercultural-style ornament, as noted long ago by Philip Kohl.25 This is borne out by its characteristic range of figural designs, which borrow skillfully from neighboring traditions of glyptic art, blending landscape elements—including natural types of flora and fauna—from sources as distant as the Indus Valley and Mesopotamia. The choice of chlorite as a decorative medium is also significant in this context. Its absorbent and insulating qualities were technologically suited to a range of cultic activities, such as the burning of unguents and the preparation of cosmetics and perfumes—objects, and composites, for all manner of special occasions.26

Vessels of this kind would have fitted especially well into a prestigious suite of commercial packages that included tree resins and oils traded northward from the Arabian side of the Gulf, where a further production center is likely to have existed on Tarut Island, in the area referred to by Mesopotamian sources as Dilmun.27 Their easily worked surfaces also invited secondary markings, as with a jar from the Inanna Temple at Nippur, to which a dedicatory inscription has been added.28 Another widely employed decorative motif was the paneled façade, associated with temple structures and ritual offerings in Mesopotamia since the late fourth millennium BC. It often appears surrounded by swirling motifs, perhaps evoking billowing fumes, and suggesting a possible function for these vessels as containers for incense or other substances burned for their fragrance and cleansing effects.

On intercultural-style vessels of the Early Bronze Age, as on international-style objects of the later Bronze Age, composite animals are rarely accorded the kind of discursive prominence that they achieved in transformative modes of transmission. Within the integrative mode, they are usually incorporated into vibrant pictorial landscapes, interacting on an equal footing with real animals as predators or protectors—a more muted visual status, in keeping with the sensitive decorum of interelite exchange. Having defined the essential features of transformative and integrative modes, a third mode of image transfer can now be identified. It is attested through an unusually rich body of evidence from Mesopotamia, casting light on the mobilization of composite animals as vehicles of protective magic, directed against the spread of disease and misfortune.

PROTECTIVE MODE: COMPOSITES DEFEND BOUNDARIES AND THRESHOLDS

To the Neo-Assyrian period in Mesopotamia, corresponding to the first half of the first millennium BC, belong cuneiform documents containing detailed instructions for the manufacture and use of composites.29 Texts of this kind have been found in the royal tablet library of Nineveh, in the House of the Exorcist at Assur, and at other urban locations. As Frans Wiggermann puts it, they prescribe “rituals for the defense of the house against epidemic diseases, represented as an army of protective intruders.”30 The rituals comprise a series of technical acts, some perhaps more symbolic than real,31 which resulted in the production of a small militia of composite figures, accompanied by images of armed deities and guard dogs. The texts also contain detailed instructions for the strategic placement of these miniature figures within and around the designated building, as a first line of defense against invisible and malevolent forces; among the equipment they carry are canonical instruments of cleansing and purification, such as the bucket and censing cone.32

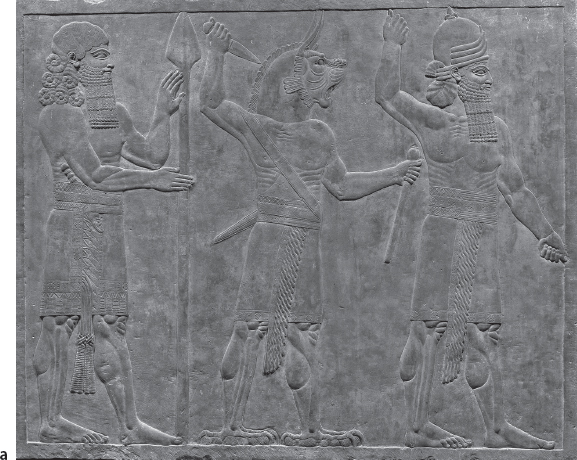

The importance of these written sources, as Wiggermann and others have pointed out, extends beyond their local contexts of storage and use. They offer direct insight into the creation and purpose of an important class of composite figures at a time when Assyrian cultural and political influence extended from the orientalizing world of the Eastern Mediterranean to the highland kingdoms of the Caucasus and western Iran.33 Moreover, the images that are their main concern can be matched with some certainty to those depicted on contemporaneous terracotta plaques and figurines, excavated from the foundations of public and private buildings (figure 6.4).34 In some cases, the descriptions of these miniature composites also accord well with the appearance of monumental figures: protective spirits that guarded the sculpted palaces of the Neo-Assyrian kings;35 and some—such as the “Scorpion-Man” and “Bull-Man’—have regional genealogies extending back to the third millennium BC.36 Wooden images of protective spirits are also mentioned in the texts, but have not survived for inspection.37

Like the demons they were intended to repel, the powers of those supernatural agents invoked in the ritual texts were ambivalent. The purpose of the rituals, and of the technical process of forming a miniature figure, was to obtain a degree of control over them, harnessing them to the domestic realm as a kind of spiritual fortification against outside threats and pollution. The texts make it clear that this could be achieved only with the aid of the gods, which was called upon through the observance of cleansing and sacrificial rites during the making of effigies, and by the consecration of their wood and clay with purifying materials: gold and silver tools for the (symbolic) cutting of wood, and precious stones such as carnelian, to be cast into the pit from which clay was extracted.38 The choice of materials is never explained, but it seems significant that all originate in distant highlands beyond the familiar world of cities, extending the spatial logic of an official worldview in which mountains constituted not just the margins of a civilized, lowland world but also its ontological opposite.39 Geographical remoteness is also directly evoked in inscriptions that empower protective spirits to send the demons “3,600 miles” away from their intended human targets, and also in the depiction of harmful demons—such as the child-devouring Lamashtu—as equipped for long-distance travel over land and sea (figure 6.5).40

6.4. Mold-made terracotta plaques (heights ca. 12 and 14 cm) with images of protective spirits, from Assur in northern Iraq, early first millennium BC (after Rittig 1977, figs. 22, 40).

Some more general observations can be made about these documents, and the associated corpus of images. The first concerns the highly structured, ritualized, and restricted genre of image production to which they belong. Neo-Assyrian composites came in standard sets and assemblages, and the rituals gave precise instructions as to their appearance and proper locations around the house. Every detail of manufacture was clearly set down: the various components of the body (including model wings, horns, and incised scales); its outer treatment with colored pastes; the written incantations to be inscribed on its surface; the weapons and instruments of purification that it was to carry; to which hand each should be attached; and in what order all these acts were to be carried out.41 The counterfactual properties of the resulting image were thereby constructed through a whole series of explicit ritual and technological procedures extraneous to its cultural form—procedures we would be quite unaware of, were it not for the survival of relevant written sources.

6.5. Stone amulet with image of Lamashtu standing on a donkey (probably early first millennium BC, acquired by Leonard Woolley and sometimes attributed to Carchemish, on the Syria-Turkish border; its provenance is in fact unclear; after Burkert 1992: 84, fig. 5).

Making a magically effective composite was then no ordinary technical act, but one guided by strict and preordained regulations, requiring access to special (and often exotic) ingredients and skills, including literacy. While the miniature clay composites of the Neo-Assyrian period may appear, on first inspection, to belong to the same general class of “popular” imagery as prehistoric figurines, their conditions of production are therefore worlds apart. Behind each composite form lurks the complex cultural apparatus of the imperial state, with its carefully administered and ever-expanding archives of occult knowledge, its stores of exotic and magical materials, and its concentration of ritual, medical, and technological expertise.42 Edith Porada perceptively observed that this centralized management of the spirit domain is surely less a proof of “terrible superstition” than of “trust in the exorcists, the ‘men of science’ of the day who had libraries of protective rituals at their disposal.”43

The ability of rulers to concentrate such skills and resources within the imperial center rendered its peripheries—to which terrifying demons such as Lamashtu did indeed travel—peculiarly vulnerable, in a way that goes beyond political or economic insecurity, threatening the psychological foundations of social life.44 It is this particular construction of the alien, composite image that may in some (but clearly not all) cases forge a link with the “transformative mode” of transmission, as defined earlier in this chapter. In his analysis of the Perseus-Gorgon myth, David Napier describes one such process, played out on the margins of Neo-Assyrian imperial and commercial influence.45 Imported composites, he suggests, were given discursive prominence in archaic Greek art as points of engagement with the foreign; as a means of encompassing and modulating the transformative effects of exposure to outside influence, in a way that served the interests of particular groups in local arenas of status competition. The face of Gorgon—prominently mounted on architectural thresholds46 and displayed on the surfaces of feasting equipment—was interlaced with characteristic forms and postures of alien composites, appearing variously on the hybrid body of a centaur or in the “mistress of animals” pose familiar from the protective imagery of the Near East. Visual experiments of this kind, according to Napier, were a matter “of attaching through iconography, and of legitimizing through mythology, images and relationships that in themselves are forceful,” reflecting the “Greek desire to have their own Gorgon be equal to or superior in power to these demons of the Near East, to compete and win out, if you will, on similar iconographic terrain.”47

COMPOSITES AS CAPITAL AND AS INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY

In exploring some of these more elaborate modes of image transfer, the more obvious entanglements of composites with the circulation of luxury goods and materials should not be overlooked. Quantities of expropriated Phoenician and North Syrian ivories, recovered from Assyrian palaces of the early first millennium BC, are just one indicator of the scale on which ornamented materials, also including decorated textiles and metalwork, moved as a consequence of political and military expansion.48 Prestige metalwork in particular, by virtue of its recyclable nature, carried intrinsic commodity value regardless of its decorative content.

Coerced movements of precious objects could also stimulate more complex processes of cultural appropriation. Mehmet-Ali Ataç provides an example in his analysis of the relationship between Ninevite palace relief and Egyptian funerary art (figure 6.6), viewed against the backdrop of Assyria’s conquests on the Nile in the seventh century BC.49 The taking of Thebes, in Upper Egypt, made available to the Ninevite court not only the imperial monuments of the New Kingdom, by then some centuries old, but also the human resources of the Egyptian palaces and temples. Among the movable assets taken to Assyria were scribes and ritual specialists, bringing with them exotic techniques of healing, protective magic, and the interpretation of dreams.50 Three millennia after their first migration from Mesopotamia to the Nile, images of composite beings—and associated forms of specialist, occult knowledge—may therefore have traveled back in the opposite direction as trophies of war.

6.6. Protective spirits from two worlds: (a) monumental relief carving of an ugallu from the North Palace at Nineveh, Iraq, ca. 640 BC (© The Trustees of the British Museum); (b) guardian figures on a funerary shrine of Tutankhamun, Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt, fourteenth century BC (after E. Hornung. 1990. Valley of the Kings. Horizon of Eternity. New York: Timken, p. 73).

SECURING BOUNDARIES IN A FRAGILE WORLD

At what is admittedly a high level of generality, the modes of image transfer defined in this chapter can be seen to share an underlying problematic. Each is associated to some degree with environments of heightened risk and uncertainty, where failure to properly negotiate boundaries can lead to catastrophic consequences. Within the transformative mode, status accrues to those groups within society who can establish stable relations with an encroaching outside world. The integrative mode is associated with the tense theater of courtly diplomacy, with its fragile alliances and fateful transgressions. And the protective mode, shading into the other two, is a direct response to threats against household and person, in which preemptive ritual attacks are launched upon the demonic carriers of illness and misfortune.

Against this backdrop, the cultural ecology of the composite figure comes into clearer focus. It can now be defined not only in terms of morphology—that is, the “fit” between composites and the technological milieu of the first cities (see chapter 4)—but also in terms of institutional dynamics. Time and again, these otherworldly anatomies provided the locus for a heightened cultural interplay between “self” and “nonself,” condensing some anticipated danger into an image that could be fixed and managed within existing structures of meaning. The cosmos occupied by composites was a fragile and fissile one, presided over by the threat of uncontrolled transformations, and confronted by the prospect of immanent corruption, marginalization, or disintegration. If we are seeking a biological analogy for their properties of transmission, then we might best look not to the field of epidemiology but to that of immunology, which centers on the procedures available to the body (and, by extension, to the body politic) for discerning and neutralizing outside threats.51