The Trouble with Growth

![]()

Peter A. Victor and Tim Jackson

In July 2013, a remarkable conference took place in a meeting hall of the French National Assembly in Paris. Current and former government ministers from France, Sweden, Greece, Spain, and Brazil, under the aegis of the president of France, François Hollande, met to explore nothing less than modern economic heresy: the abandonment of governments’ longstanding commitment to continuous economic growth—and its replacement, at least in the view of some attendees, with goals focusing on well-being, equality, and environmental health.1

The conference was remarkable not only for the number of officials willing to think outside the conventional economic box, but because the topic barely registers on the radars of officials outside Europe, and is even less known to the general public. Indeed, the need for economic growth continues to be unquestioned dogma in most of the world, even in governments that claim to be striving for sustainability.

Concern over the ongoing expansion of the world’s economies is driven largely by the unsustainable burden that this relentless growth imposes on the planet’s life-support systems. Evidence of this burden has been accumulating for decades. For example:

• Five assessment reports issued by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change between 1990 and 2014 document, with steadily increasing certainty, the growing human influence on Earth’s climate.

• The 2005 Millennium Ecosystem Assessment concluded that roughly 60 percent of the services provided by nature to humans are in decline.

• Work since 2009 on “planetary boundaries” has identified factors that drive nine major environmental phenomena—including climate change, biodiversity loss, and nitrogen pollution—and suggests that in several cases the boundaries have already been crossed.

• The 2014 Living Planet Report documents that populations of vertebrate species have declined by half since 1970.2

Peter A. Victor is a professor of environmental studies at York University. Tim Jackson is a professor of sustainable development at the University of Surrey and also an ESRC professorial fellow on Prosperity and Sustainability in the Green Economy (PASSAGE).

These and other compelling studies pose a strong challenge to modern ideas of progress, and they suggest that a commitment to economic growth is a hidden threat to sustainability. Fortunately, humans have millennia-worth of experience building economies that are not driven by a growth imperative. And today, research suggests that modern economies could provide jobs and reduce inequality (perhaps more effectively than today’s economies do)—even as they lighten humanity’s impact on the environment—without pursuing economic growth. Given the need for economies designed to grow slowly or not at all, especially in physical terms, the question is whether policy makers and the public worldwide can summon the courage and open-mindedness to forgo economic growth as a policy priority.

Economic Growth as a Policy Objective

Anyone born after the middle of the twentieth century can be excused for thinking that economic growth has always been a top priority for governments. But as Heinz W. Arndt observed in his history of economic growth, “There is in fact hardly a trace of interest in economic growth as a policy objective in the official or professional literature of western countries before 1950.” This will come as quite a surprise to those accustomed to the endless stream of statements by politicians, pundits, the media, and economists about the importance of economic growth.3

Economic growth as a policy objective emerged after World War II as an effort by governments to achieve full employment for their citizens. In the 1930s, British economist John Maynard Keynes had argued persuasively that while no mechanism exists in the private sector of capitalist economies to guarantee full employment, government spending could be used to prime the economic pump and stimulate job creation. His theoretical arguments were borne out by the experience of World War II, during which government spending increased dramatically, especially among the Allied nations, and unemployment largely disappeared.4

During and following the war, with the bread lines of the Great Depression fresh in their memories, governments in many countries adopted full employment as an explicit policy objective, believing that Keynes had equipped them with the means to achieve it. Full employment required that total expenditures rise continually to pay for the new infrastructure, factories, and equipment that made full employment possible. So governments began to pursue economic growth as a means of achieving their full employment goals. Within a few years, likely because of the Cold War and the global arms race, economic growth became an objective in its own right.

In 1960, member countries of the newly established Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) declared in the organization’s charter that: “The aims of the OECD shall be to promote policies designed to achieve the highest sustainable economic growth and employment and a rising standard of living in Member countries.” From then on, economic growth has been among the top economic policy objectives of governments, not only in OECD member countries, but in international organizations and countries around the world. (See Box 3–1.)5

Box 3–1. What Is Economic Growth?

Economic growth refers to an increase in the goods and services produced by an economy during a given period, as measured by the rate of change in gross domestic product (GDP), excluding inflation. In its simplest terms, GDP is a measure of economic activity—or “busyness”—in an economy.

When GDP is divided by population, the result is GDP per capita, which is often used to measure the “standard of living” of a country. Some countries, such as Luxembourg and Singapore, have very high GDP per capita, even though their total GDPs are low. China and India have large GDPs, but relatively low GDP per capita. GDP and GDP per capita are snapshot measures of an economy. Economic growth is about their change over time.

The benefits of economic growth are distributed unequally within and among countries. The same is true of the costs of economic growth. For example, climate change, caused mainly by the emission of greenhouse gases when energy is used to power economic growth, is just one of many examples of this maldistribution of costs: those most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change have been the least responsible for causing it.

The important point is that belief in the indispensability of economic growth, while deeply rooted in governments virtually worldwide, is quite recent. The common view that growth has always been an important objective of government is mistaken. That growth is inextricably bound up with human nature is an even greater mistake, if it makes us think that there really is no alternative to economic growth. Understanding that growth is not a necessary goal of government policy is critical if we are to imagine alternative economic futures.

The Negative Consequences of Economic Growth

While economic growth has brought higher living standards and jobs for many people, along with tax revenues for governments, it has been achieved at the cost of depleted soils and aquifers; degraded lands and forests; contaminated rivers, seas, and oceans; disrupted cycles of carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorous; and more. In short, economic growth is not an unqualified good. And these environmental costs, along with the social costs of unequal growth, can be substantial.6

In the 1970s, economist Herman Daly considered the possibility that economic growth can have such serious negative consequences that they outweigh the benefits of growth. When growth does more harm than good, he explained, it should be described as “uneconomic,” since it results from an uneconomical use of resources. Daly and his colleagues developed the Index of Sustainable Economic Welfare (ISEW) to capture the good and bad of economic growth and to give a more accurate measure of economic advance. The ISEW subtracts from GDP the value of unwanted side effects of economic activity—such as the costs of commuting; “defensive” private expenditures on health; pollution; and the depletion of natural resources—and adds in the value of activity that advances well-being and is overlooked by GDP, such as unpaid household work.7

Nick Normal

Used windows available for reuse at a nonprofit center in Queens, New York.

Daly’s team concluded that in the United States from 1950 to 1990, ISEW per capita increased far more slowly than GDP per capita—well-being lagged far behind output—and that in the final decade (1980–90), ISEW per capita actually declined. Uneconomic growth had arrived in the United States. Similar studies for other countries and regions using the ISEW and its sister measure, the Genuine Progress Indicator, have produced similar results.8

In view of the increasingly mixed record of economic growth, Daly concluded that an alternative to growth economies was needed. He advocated for a “steady-state” economy in which the materials and energy used to produce goods and services is kept roughly constant (through recycling, substitution of services for goods, and other materials-saving strategies). Daly distinguished between growth and development, arguing that economies could and should continue to develop indefinitely, but without growth of the economy’s material requirements.9

Defenders of economic growth often assert that slow or no growth will result in mass unemployment and misery, that the best way to reduce the costs of economic growth is more growth, and that prices and technology will ensure that economic growth is sustainable over the long run. Even many advocates of sustainable economies argue that growth is necessary. The Global Commission on Climate and Economy, led by Sir Nicholas Stern, launched its recent New Climate Economy report under a bold headline in favor of “better climate, better growth.” Meanwhile, the OECD’s annual Going for Growth report continues to advise member countries on how to increase their rates of economic growth, even though other reports from the OECD propose “green growth” and “inclusive green growth,” adding a social justice dimension.10

Thus, the critique of growth, which has a long and serious pedigree, has generated serious pushback. Who is correct—the critics of growth or its defenders? Central to the debate is the answer to these questions: Can economic growth be designed in a way that reduces its “uneconomic” costs, even as growth continues indefinitely? Or must growth be abandoned in order to put the world’s economies on a sustainable path?

Decoupling Economic Growth from Throughput

The environmental costs of economic growth come from the increasing use of “throughput”: the materials (i.e., biomass, construction materials, metals, minerals, and fossil fuels) used to support economic growth. Obtaining increasing supplies of these materials has led to deforestation, the degradation and loss of soil, the removal of massive quantities of material to access underground resources, transformation of the landscape, and more-frequent and more-serious pollution as ever more remote sources of materials, especially fossil fuels, are accessed. Most of these materials remain within the economy for a very short time: fuels for only moments upon use, and many other materials, even with recycling, for less than a year—although some remain much longer, such as building materials and precious metals.11

After use, these discarded materials and the dissipated energy are disposed of back into the environment, which has a limited capacity to absorb them. When this capacity is exceeded, a wide range of environmental problems arise. In the early days of industrialization, these problems were primarily local (e.g., polluted rivers and urban air, municipal waste dumps, mine tailings), but with global economic expansion, the associated environmental problems became regional (e.g., acid rain, hazardous waste shipment and disposal) and now global (e.g., acidification of the oceans, loss of biodiversity, climate change).

A critical question is whether throughput, especially those components that do the most damage, can be decoupled from economic growth. If it can, then at least the environmental reasons for questioning the sustainability of economic growth can be addressed. Some analysts are very optimistic about the potential for decoupling growth from throughput, by shifting consumption from goods to services, better design of products and processes, recycling more, substituting scarce materials with more abundant ones, and replacing fossil fuel energy with energy from renewable sources.12

Significant improvements in efficiency are possible, especially if determined efforts are made to achieve them. It is by no means certain, however, that these actions will be sufficient to meet wide-ranging economic, social, and environmental objectives, especially in the long term. Ernst von Weizsäcker and his colleagues speak of a “factor 10” economy in which the throughput requirements per dollar of GDP are reduced by a factor of 10. Such a reduction would allow economies to increase their GDP 10 times without any increase in throughput. Alternatively, they could reduce their throughput by 50 percent if GDP increased only five times.13

This tradeoff between GDP growth and throughput reduction has two critical implications. First, the greater the rate of economic growth, the faster must be the decline in the rate of throughput (i.e., throughput per unit of GDP) to achieve any desired level of total throughput reduction. There already are many indications that the capacity of the biosphere to absorb the wastes generated by the world’s economies has been exceeded in several important respects. Therefore, global throughput will have to be reduced as swiftly and as equitably as possible, to bring economic and environmental systems back into some sort of balance. And this is without considering that some components of throughput (e.g., radioactive waste, heavy metals, carbon emissions) accumulate in the biosphere, requiring even greater reductions in throughput to achieve reduction targets. Hence, some decoupling is required even in the absence of economic growth. But even more decoupling is required if economies grow, and the faster they grow the faster must be the rate of decoupling.

The second critical implication of the relationship between rates of economic growth and decoupling is to consider what happens after a substantial, say tenfold, increase in GDP—even assuming a tenfold or more level of decoupling. An economy growing at 3 percent per year will experience a tenfold increase in GDP after 78 years, which is about the average lifetime of a person born in an industrialized country. Throughput per dollar of GDP will have to shrink to 10 percent of its current value over that period to avoid an increase in total throughput, which is very ambitious. After that, if economic growth continues for another human life span without an increase in throughput, throughput per dollar will have to be only 1 percent of what it is today simply to avoid an increase in the total. At some point, this process must come to an end and economic growth must cease if sustainability is to be achieved.

These arithmetic examples can help scope out the extent to which decoupling is required, but they cannot tell us anything about what might be feasible. Fortunately, Vaclav Smil makes a recent attempt to assess feasibility in his book Making the Modern World: Materials and Dematerialization. Smil provides a comprehensive, detailed account of decoupling from the first Industrial Revolution to the present day. He makes the important distinction between relative and absolute decoupling, as others have done. Relative decoupling is about reductions in throughput per dollar of GDP, and absolute decoupling occurs when total throughput, or some important component of it, declines while GDP increases. Smil provides plenty of evidence and numerous examples of relative decoupling, and he expects it to continue well into the future. In contrast, he is very skeptical about the prospects for absolute decoupling, and yet this is what those who maintain that growth can continue indefinitely rely on.14

Relative decoupling does not automatically lead to absolute decoupling for a number of reasons. The first is the Jevons paradox, an insight put forward by William S. Jevons in his 1865 study of Britain’s coal industry, which revealed that improvements in efficiency lead to reductions in operating costs, but that lower operating costs often induce increases in use. It is “a confusion of ideas to suppose that the economical use of fuel is equivalent to diminished consumption. The very contrary is the truth.” The Jevons paradox, or “rebound effect” as it is now sometimes called, is a pervasive relationship that explains much of the disconnect between relative and absolute decoupling.15

João Ramid/Norsk Hydro ASA

Bauxite ore being stockpiled at a mine in northern Brazil.

The other two factors that explain the disconnect between efficiency improvements and absolute reductions in throughput are increases in population and increases in the general level of consumption.

Concluding his book, Smil writes, “to stress the key point for the last time, these impressive achievements of relative dematerialization have not translated into any absolute declines of material use on the global scale.” He goes on to say that “the global gap between the haves (approximately 1.5 billion people in 2013) and the have-nots (more than 5.5 billion in 2013) remains so large that even if the aspirations of the materially deprived four-fifths of humanity were to reach only a third of the average living standard that now prevails in affluent countries, the world would be looking at the continuation of aggregate material growth for generations to come.”16

So much for global decoupling. At the national level, Smil observes that, “Clearly, there is no recent evidence of any widespread and substantial dematerialization—be it in absolute or . . . per capita terms—even among the world’s richest economies.” However, he does point to Germany and the United Kingdom as examples of a few countries where “overall material inputs have stabilized or have even slightly declined . . . while some of their specific inputs continued to rise.” Smil acknowledges that this promising result may be due to changes in trade patterns, and this is exactly what has been shown in other research studies. The shift in manufacturing from industrialized to developing countries has entailed a shift in the location of where materials enter the interconnected economies of the global economic system, rather than any real reduction.17

Another recent study by Tommy Wiedmann and colleagues traces the material inputs (i.e., biomass, construction minerals, fossil fuels, and metal ores) embedded in the consumption of 186 countries from 1990 to 2008, and makes very clear the connection between international trade and the absence of absolute decoupling. The authors conclude: “As wealth grows, countries tend to reduce their domestic portion of materials extraction through international trade, whereas the overall mass of material consumption generally increases. With every 10% increase in gross domestic product, the average national MF increases by 6%.” MF refers to the “material footprint” of nations, which includes all of the materials used to support consumption in countries irrespective of where the materials are obtained.18

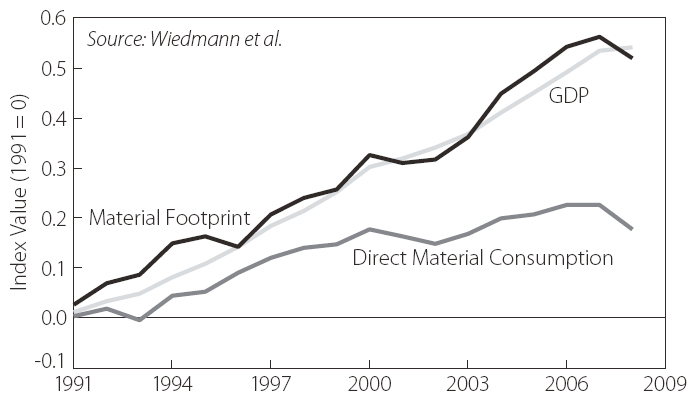

Wiedmann and colleagues observe that: “The EU-27 [27 member countries of the European Union], the OECD, the United States, Japan, and the United Kingdom have grown economically while keeping DMC [direct material consumption] at bay or even reducing it, leading to large apparent gains in GDP/DMC resource productivity. In all cases, however, the MF has kept pace with increases in GDP and no improvements in resource productivity at all are observed when measured as the GDP/MF.” These findings are illustrated in Figure 3–1, where from 1990 to 2008, the material footprint of OECD countries in total moved in step with GDP, while their direct material consumption showed relative decoupling (and absolute decoupling during recessions).19

The most reasonable conclusion to draw from studies such as those of Smil and Wiedmann et al. is that there is very little precedent for absolute decoupling and no foundation of experience on which to base a realistic expectation for the degree of decoupling required for sustainability. So while one may speculate boldly about the future prospects for absolute decoupling of throughput from economic growth, and thus maintain that economic growth can continue without limit, such speculation finds virtually no support in the historical record.

Envisaging Alternative Futures

Interest in alternatives to economic growth goes back a long way in the history of economics. In 1848, John Stewart Mill devoted a chapter in his Principles of Political Economy, an influential book for several decades, to a consideration of the “stationary state.” He was motivated to do so not because of a concern that economic growth could not continue, but because of what it was doing to life in Britain as he saw it. Although Mill’s language comes from an earlier age, his sentiments are surprisingly modern: “I am not charmed with the ideal of life held out by those who think that the normal state of human beings is that of struggling to get on; that the trampling, crushing, elbowing, and treading on each other’s heels, which form the existing type of social life, are the most desirable lot of human kind, or anything but the disagreeable symptoms of one of the phases of industrial progress. . . . The best state for human nature is that which, while no one is poor, no one desires to be richer, nor has any reason to fear being thrust back, by the efforts of others to push themselves forward.”20

Figure 3–1. Material Footprint “Decoupling” in OECD Countries, 1991–2008

Mill was careful to acknowledge that, in developing countries, “increased production is still an important object,” and that, “in those most advanced [countries], what is economically needed is a better distribution, of which one indispensable means is stricter restraint on population.” Mill understood that in a stationary state, there would still be ample opportunity for technology to improve the quality of life, for example, by reducing time spent at work. He decried the extent to which humans were transforming land from its natural state and eliminating animals and plants that were not domesticated. He concluded his remarkable chapter on the stationary state by expressing the “hope, for the sake of posterity, that they [the population] will be content to be stationary, long before necessity compels them to it.”21

Numerous writers, including several notable economists such as Keynes, Daly, and E. F. Schumacher, have cast their minds forward in contemplation of a future very different from their own times. A theme of particular interest is understanding what might be possible in advanced economies in the absence of economic growth and reductions in throughput. Would these economies collapse without growth? Would mass unemployment result? Could the existing institutions—in particular, financial institutions—survive without growth, and if not, what sort of changes might be required? What would be the implications for economic growth of strict limits on throughput?22

These and other questions are the focus of ongoing research based on an integrated approach that includes: 1) the financial system, with a central bank and commercial banks where money is created, credit is advanced, and interest paid; 2) the real economy, where resources are allocated and goods and services are produced and distributed; and 3) the throughput flows that link the real economy to the biosphere. This research, using simulation models and comprehensive databases, has shown how a different approach to labor productivity could improve the prospects for higher levels of employment, even in the context of declining economic growth rates. It also has shown that declining growth rates need not necessarily lead to high levels of inequality. At the local level, research has investigated the implications for communities of slow or no economic growth, focusing on enterprise, employment, investment, and finance.23

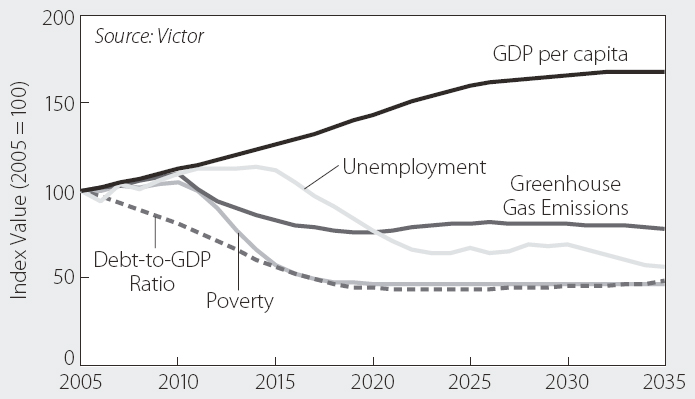

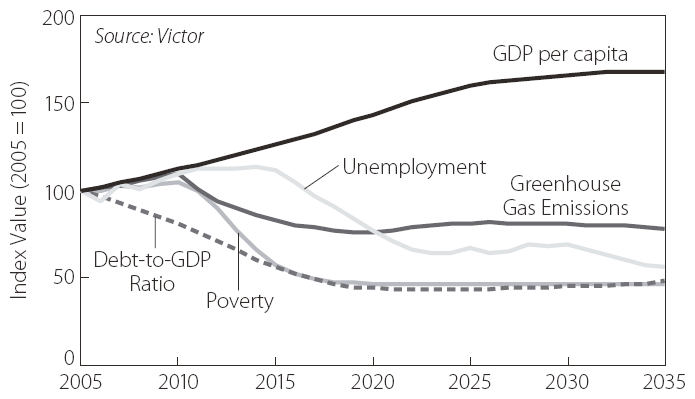

An earlier attempt to develop a model (termed “LowGrow”) for scoping out alternative futures for Canada illustrates the kinds of insights that simulation models of economies can generate. In LowGrow, as in the economy that it represents, economic growth is driven by: net investment, which adds to productive assets such as machinery, buildings, and infrastructure of all types; growth in the labor force; increases in productivity; growth in the net trade balance (i.e., exports minus imports); growth in government expenditures; and growth in population. Low-, no-, and de-growth scenarios can be examined by reducing the rates of increase in each of these factors singly or in combination. One promising scenario is shown in Figure 3–2.24

Figure 3–2. A Low-/No-Growth Scenario for Canada, 2005–2035

In this scenario, growth in GDP per capita slows until it levels off completely around 2030, at which time the rate of unemployment is 4.7 percent. The unemployment rate continues to decline to 4.0 percent by 2035, a rate that Canada has not seen for 50 years. By 2020, the United Nations poverty index declines from 10.7 to an internationally unprecedented level of 4.9, where it remains, and the debt-to-GDP ratio (a common measure of government fiscal performance) declines to about 30 percent, to be maintained at that level to 2035. Greenhouse gas emissions are 31 percent lower at the start of 2035 than 2005, and are 41 percent lower than their high point in 2010.

These results are obtained in LowGrow by slower growth in government expenditure, net investment and productivity, a small positive net trade balance, cessation of growth in population, a reduced workweek, a revenue-neutral carbon tax, and increased government expenditure on anti-poverty programs, adult literacy programs, and health care. There would still be plenty of opportunity in this scenario for technological advance, but it would be directed toward reduced throughput and away from activities that undermine sustainability.

The scenario in Figure 3–2 shows that even without economic growth, a range of desirable economic, social, and environmental objectives can be achieved. However, it would be a mistake to interpret this scenario as suggesting that zero economic growth, measured conventionally as increasing real GDP, should become an economic policy objective in its own right. From a sustainability perspective, what matters is an absolute reduction in throughput and land transformation degrading the soil and destroying habitat. These are necessary conditions for sustainability. Achieving them through strict controls that reduce throughput and rebuild ecosystems may well require a reduction in the rate of economic growth. It might also entail a period of degrowth until the economy’s burden on the environment, in rich countries to start with, is sufficiently moderated. The main lesson from a scenario such as the one in Figure 3–2 is that we should not shy away from measures necessary for sustainability on the grounds that they will undermine economic growth.25

It is interesting to consider what life would be like under such a scenario. Much would depend on whether the scenario is adopted broadly, enthusiastically, and democratically, or whether the economy simply stagnates, as some fear is already happening, and nothing is done to alleviate the social stresses and friction that inevitably would result. In the sort of positive possibility envisaged here, there will be many changes. For example, rather than using gains in productivity to produce more goods and services, people would have more leisure time to spend with friends and family, and to participate in community life. Rampant financial speculation of the kind that brought widespread misery in 2008–09, and that still threatens, would be avoided through new banking structures and regulations. This would help facilitate a redirection of investment away from the endless and ultimately pointless search for social status from consumption, and toward increased investment in a wide range of public goods, such as community facilities, better infrastructure, and the protection and enhancement of air, water, soils, and ecosystems.

With much slower or no economic growth, it will no longer suffice to say that poverty will be eliminated through economic growth, a claim that has been proven wrong even on its own terms. In recent decades, most of the gains from economic growth have been restricted largely to the top few percent of the population. All Western countries have had experience with redistribution programs: progressive income taxation, inheritance taxes, income-support programs, universal health and education programs, low-income housing, and so on. More-equitable distribution can also involve greater use of cooperatives and more widely shared ownership. While redistribution through these kinds of instruments and institutional structures has fallen into disfavor in recent times, often in the name of economic growth, we expect them to play a vital role as we move toward a sustainable future.26

Alex

Coal-fired Navajo Generating Station near Page, Arizona.

Conclusion

As the discussion above suggests, the pursuit of endless economic growth is a threat to sustainability. Most economists and governments are reluctant to come to grips with the implications of economic growth for the biosphere, preferring instead to hold out hope for absolute decoupling, to be delivered by a combination of technological change and a switch to a more service-based economy. Both of these avenues of change are important. But the existing evidence suggests that absolute decoupling of economic growth from throughput is unlikely: the historical record shows very little evidence of absolute decoupling, and assumptions about future decoupling are heroic at best.

History also shows that the pursuit of economic growth as a policy objective (and indeed as an object of academic study) is comparatively recent, going back only to the 1950s. Meanwhile, critiques of growth for growth’s sake are longstanding, dating back to the 1800s. Achieving prosperity in its fullest sense is not at all synonymous with expanding the economy indefinitely. These considerations suggest that it is possible—and indeed desirable—to move public policy objectives away from the pursuit of economic growth, and toward specific goals that are more directly related to the well-being of humans and other species.

There are many good reasons for undertaking such a shift. One reason is that in much discussion about policy, economic growth is often used as a trump card. If protection of the environment threatens economic growth, then it is too bad for the environment. Hence the current interest in “green growth,” with its false promise of even faster economic growth. Support for the arts, for sports, for child care, for less inequality, for better access to public goods, or for greater environmental protection all too often depends on whether a case can be made that it will promote economic growth, or trade, or competitiveness, or productivity, or some other growth-promoting consideration.

Our preoccupation with economic growth often has impeded action on issues that really will improve human well-being and the prospects for all life on Earth. This is the trouble with growth. If we insist on continuing to make economic growth the priority, we will deprive ourselves, and our descendants, of a sustainable future. It is time to remove the growth trump card. The pursuit of economic growth should no longer be a threat to sustainability.