Whose Arctic Is It?

![]()

Heather Exner-Pirot

The rapid changes occurring in the Arctic region in the past 10–20 years have become one of the biggest stories in climate change. Temperatures in the Arctic are rising higher than anywhere else on Earth—and more quickly as well. Sea ice has been melting in the summer season at an astonishing rate, and scientists are only beginning to understand the consequences of this thaw for global climate patterns. Many marine species are being affected dramatically by changes in the Arctic environment, with the plight of the polar bear in particular becoming popularized as a symbol of the negative consequences of Arctic warming and global climate change.

In tandem with a warming environment has come growing economic and political interest in the Arctic. Less sea ice ostensibly means more opportunities for shipping and resource extraction, and, troublingly for many, it could result in the opening of previously inaccessible offshore oil and gas fields in the Arctic Ocean and its outlying seas. The “Arctic Paradox”—the irony that global warming related to the burning of fossil fuels will result in new sources of these fuels being extracted in the Arctic—has made the region the most important battleground in the war against climate change.

But that is not the only way to view the Arctic. Although most people in the cities of Europe, North America, and elsewhere seem to see the Arctic through a lens of either climate change or economic opportunity, there is another, often ignored perspective: that of the peoples of the North, for whom the Arctic is not an abstract environmental object but rather a homeland, a workplace, and a community. Many of those who live across the circumpolar north have worked relentlessly over the past 40 years to regain self-determination from national governments and other interests, only to once again feel marginalized by political actors in the mid-latitudes who claim the Arctic as a global commons that is subject to their global governance.

Heather Exner-Pirot is strategist for outreach and indigenous engagement in the College of Nursing at the University of Saskatchewan, Canada, and managing editor of The Arctic Yearbook, produced by the Northern Research Forum and the University of the Arctic Thematic Network on Geopolitics and Security.

The Global Arctic and Climate Change

The Arctic often has loomed large in the general public’s understanding and perception of climate change. This is due to a combination of environmental and social factors:

Environmental factors. The Arctic, together with the Antarctic Peninsula, has undergone the greatest regional warming on Earth in the past few decades, due to various feedback processes. In the first half of 2010, air temperatures in the Arctic were 4 degrees Celsius (°C) warmer than during the 1968–96 reference period while, over the past half century, much of the Arctic experienced warming of over 2°C, with relative warming increasing at higher latitudes. (See Figure 7–1.)1

Figure 7–1. Mean Increase in Global Surface Temperature by Latitude in 2008–2013, Compared to 1951–1980 Baseline

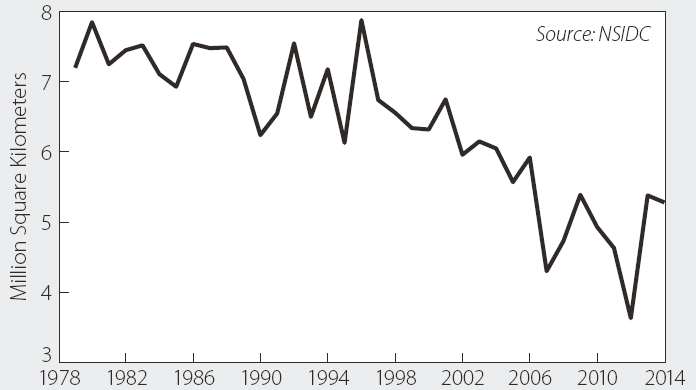

The consequences of Arctic warming are now well known and scientifically documented. Most dramatic has been the loss of summer sea ice, which reached a record low in 2012 of 3.6 million square kilometers, or 52 percent below the 1979–2000 average. (See Figure 7–2.) Overall, summer ice minimum extent, which occurs every year in September, has declined 13.3 percent per decade relative to the 1981–2010 average. Trends are much weaker, although still significant, for the winter ice maximum, occurring every year in March, showing a loss of 2.6 percent per decade.2

The loss of sea ice is having a positive feedback effect on the region’s climate, creating a situation wherein Arctic warming leads to more Arctic warming. Because white snow and ice strongly reflect solar energy, when sea ice and glaciers shrink, the newly exposed darker waters and lands absorb more solar energy. One study estimates that this absorption is equivalent to as much as one-quarter of the global warming that has resulted from human-caused carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions.3

In another positive feedback mechanism, as the Arctic warms so too does the land-based permafrost that covers large swaths of the region. When permafrost heats up, it releases methane, a powerful, short-lived greenhouse gas that over a 20-year span traps more than 85 times as much heat as CO2. Additional methane is being released in plumes from the thawing Arctic sea bed.4

Beyond warming, the increase in CO2 levels has led to widespread oceanic acidification. Surface ocean waters worldwide are 30 percent more acidic now than at the start of the Industrial Revolution in the late eighteenth century. The Arctic Ocean is especially vulnerable to acidification both because of the large quantities of fresh water that enter the basin (due in part to warming) and because of the water’s coldness, which facilitates the transfer of CO2 from the air into the ocean. Acidification threatens the ocean’s shell-building mollusks in particular, weakening their shells and contributing to population declines, which, in turn, affect marine species all the way up the food chain. (See Chapter 6, “The Oceans: Resilience at Risk,” for additional discussion.)5

Figure 7–2. Average Arctic Sea Ice Extent in September, 1979–2014

Social factors. While the Arctic is being altered observably by climate change, there is a history behind how the region became emblematic of climate change in the popular narrative. First came the science: in 2004, the Arctic Council, the pre-eminent intergovernmental forum for the eight Arctic countries (Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden, and the United States), released its Arctic Climate Impact Assessment (ACIA), prepared over five years by an international team of more than 300 scientists, local stakeholders, and other experts. The report presented definitive, scientific evidence of the impacts of climate change in the Arctic and was sanctioned by all eight countries at a time when the issue was still extremely political and contentious.6

Leveraging the legitimacy that the ACIA gave to the issue of climate change, in December 2005, Sheila Watt-Cloutier, a Canadian Inuit activist from Kuujjuaq, submitted a petition to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights in her capacity as chair of the Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC) claiming that the U.S. government’s refusal to limit U.S. greenhouse gas emissions threatened Inuit human rights. Although the petition was not successful, it helped shift public and media attention on climate change from the Antarctic, where the Larsen B ice shelf had famously collapsed in 2002, toward the Arctic region.7

Polar Cruises

A young polar bear hopping ice floes.

Former U.S. vice president Al Gore’s 2006 documentary, An Inconvenient Truth, further entrenched the Arctic as one of the foremost battlegrounds for climate change in the public’s mind, with his animated segment of a polar bear struggling to stay afloat amid a lack of ice floes on which to rest and hunt. The impact of a warming Arctic on polar bear populations has become a popular symbol of the need to take action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

In the past few years, it has become cliché for politicians, scientists, commentators, and journalists to remark that, “what goes on in the Arctic doesn’t stay in the Arctic.” Among the most obvious implications of a changing Arctic for the global environment is rising sea levels. As Arctic ice (particularly the land-based Greenland ice sheet) melts, it will contribute to an influx of water to oceans around the world. According to one study, the combined loss from the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets contributed to sea-level rise of around 1.3 millimeters in 2006, and that rate is accelerating. Since 1900, global average sea level has risen by about 18 centimeters. Hundreds of millions of people live in areas that are prone to flooding, and a majority of the world’s big cities are along coasts. A melting Arctic is putting these populations increasingly at risk.8

A warming Arctic also may affect weather conditions in the northern hemisphere, as it influences the circulation patterns of the jet stream. There has been some suggestion, based on scientific observations, that the infamous polar vortex—which, in late 2014, brought a harsh winter to much of central and eastern North America as well as to other parts of the northern hemisphere—was linked to climate change and the resulting loss of Arctic sea ice.9

The Arctic Region, from the Perspective of the Arctic Region

Considering the dramatic implications of a changing Arctic for the earth’s environment, perhaps it is no wonder that many activists in urban and mid-latitude areas have made the Arctic a cause célèbre. Perhaps most (in)famous is Greenpeace’s “Save the Arctic” campaign, which, according to the group’s website, seeks to “defend polar bears,” “stop oil spills,” and “save our planet” by petitioning world leaders to “create a global sanctuary in the uninhabited area around the North Pole” and to impose “a ban on oil drilling and destructive fishing in Arctic waters.” The European Parliament similarly voted in October 2008 to pursue “international negotiations designed to lead to the adoption of an international treaty for the protection of the Arctic, having as its inspiration the Antarctic Treaty.”10

In general, such promulgations have been anathema to both Arctic states and Arctic peoples. Much of the fault lies in how some southern (i.e., non-Arctic) organizations and politicians have characterized (and caricaturized) the Arctic as a sort of Wild West, where resource exploitation occurs without regulation and oversight, where local populations are defenseless victims of climate changes, and where the region is in need of “saving” by external actors.

ICC Chair Okalik Eegeesiak, a Canadian Inuit from Iqaluit, summed up the situation eloquently at the Arctic Circle conference in Reykjavik, Iceland, in November 2014:

For whatever reason, many newcomers to the Arctic often see it as a governance vacuum or a region that should be considered a common heritage of mankind. These perceptions overlook the people who live in the Arctic and minimize the importance of existing governance systems. . . .

When I come to these conferences and hear all the plans that people from other parts of the world have for the Arctic, I sometimes feel a bit nervous. . . . We ask that you consult with us before you try to reinvent the Arctic according to your own interests. If you want to help the Arctic, I encourage you to think about what you need to do differently in the South . . . rather than suggesting how to govern ourselves differently in the North. Consider how your activities in the South are impacting us in the Arctic and make some adjustments closer to home.11

Consider the irony, from a northern perspective, of southerners beseeching local Arctic communities and governments to make lifestyle changes and to apply bans and moratoriums on drilling, resource extraction, shipping, and fishing in order to reduce the impacts of climate change—impacts that have arisen almost entirely because of activities in southern locales. Northerners are being asked to disproportionately bear the burden of mitigating climate change, even as they disproportionately bear the burden of adapting to those changes.

There is no doubt that northerners have the greatest interest and stake in good environmental stewardship of the region. But it is curious how the Arctic, unlike other inhabited regions of the world, has become a candidate to be a “common heritage of mankind,” rather than a political region managed through the same basic processes and governance principles that apply to every other inhabited region in the world—principles that attempt to balance economic, environmental, and social priorities. This is particularly remarkable given that the existing environmental management in the Arctic is as good as, or arguably better than, that in any other region on Earth.

Current Arctic Governance Mechanisms

A variety of mechanisms are currently in place to govern activities in the Arctic Ocean as well as in the various lands of the Arctic region.

Arctic Ocean jurisdiction. The Arctic Ocean basin is juridically divided almost entirely among the five Arctic countries that have shorelines on the Arctic Ocean: Canada, Denmark, Norway, Russia, and the United States (Alaska). Finland and Sweden have no Arctic coasts, and Iceland is considered to be located in the North Atlantic. The United Nations (UN) Convention on the Law of the Sea generally grants countries sovereignty over their territorial waters, which extend 12 nautical miles (22.2 kilometers) from their respective baselines (average low water mark). It also gives special rights regarding exploration and use of marine resources in the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), which extends 200 nautical miles (370 kilometers) from baseline. In cases where the continental shelf extends beyond the EEZ, coastal countries may claim seabed rights to an even wider area.12

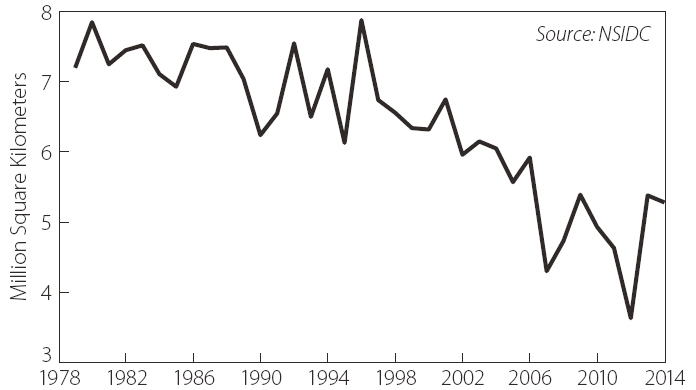

In practice, this means that it is entirely acceptable under current international law for Arctic countries to drill or fish in their respective EEZs, far into the Arctic Ocean. And if the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf* accepts countries’ current bids to extend (or “prolong”) their continental shelf areas, more than 90 percent of the Arctic Ocean would likely fall under some level of national jurisdiction under existing international law. (See Figure 7–3.) International shipping access, however, is unaffected in the EEZ except in internal or territorial waters.13

It is extremely unlikely that countries would give up accepted rights to Arctic territory that is already theirs under current international law, and choose instead to adopt an Antarctic Treaty-like regime that shares governance with countries or other actors from outside the Arctic region. This does not mean that national and international legal mechanisms governing the Arctic Ocean basin do not exist—and, indeed, several new ones are under consideration. But it does mean that calls for shared governance arrangements and/or the relinquishing of existing sovereign rights are unrealistic and therefore not constructive, and the five countries with Arctic Ocean shorelines have rejected such calls.

World Ocean Review, maribus gGmbH

Only the areas marked in dark gray are unlikely to be claimable by Arctic countries.

Jurisdiction over the lands of the Arctic region. It goes without saying that the eight Arctic countries—the five with Arctic Ocean shorelines, plus Finland, Iceland, and Sweden—have sovereignty over the lands within their national boundaries. It should be noted, however, that the Arctic region is home to many innovative governance arrangements that have granted northern sub-national entities and indigenous groups special rights and particular levels of self-governance. These include:

• The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1972, which transferred approximately 40 million hectares of public land to native Alaskans, along with a $963 million settlement;

• In Greenland, the attainment of Home Rule in 1979 and then Self-Rule in 2009, which transferred control over a wide variety of governance functions from Denmark to Greenland, including the right to revenues from non-renewable resource development;

• The establishment in Canada of the territory of Nunavut in 1999 and the settlement of land claims in the four Canadian Inuit regions of Nunavik (1975), Inuvialuit (1984), Nunavut (1993), and Nunatsiavut (2005); and

• The negotiation in Canada of the Yukon First Nations Land Claims Settlement Act in 1994, as well as the devolution of additional governance functions to Yukon in 1993 and 2001 and to the Northwest Territories in 2013.14

The larger point is that the Arctic region has been undergoing a process of devolution of lands and governing power to regional northern polities—particularly those of indigenous origins—for five decades. The decentralization of political processes and acknowledgement of the indigenous right to self-determination has faced many challenges, but it is widely accepted as the best pathway toward improving quality of life for northern inhabitants.

Arguments originating in southern locales in favor of reinventing the Arctic as a global commons, governed by global interests, are in stark contrast to these efforts to restore governance powers to local communities. It is similarly simplistic to call on Arctic countries to impose bans or moratoriums or to develop laws that may infringe or conflict with the rights that have been granted, sometimes constitutionally, to northern and indigenous inhabitants within their national boundaries. Environmentalists and climate advocacy groups should be reassured by the fact that many of these land claims and governance arrangements include mandatory environmental impact assessments and regulatory processes that are generally as robust, or more so, than standard national regulatory procedures.

Regional and International Environmental Governance

One of the more pervasive myths about the Arctic Ocean is that it is ungoverned. While it is true that some of the common governance structures that are in place in other, more accessible, regional seas are absent in the Arctic, this is largely because the vast majority of the Arctic has been inaccessible to human activity until very recently (aside from subsistence use), and so regulation was moot. Commercial fishing in the Arctic Ocean, for example, has been largely hypothetical until very recently, and shipping is still very limited in Arctic waters.

Because the Arctic region is mostly under the jurisdiction of countries, existing international law applies in the region. Among the major treaties that apply to the Arctic are: the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea*, the Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movement of Hazardous Wastes and Their Disposal, the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, the UN Convention on Biological Diversity, a broad range of conventions and other instruments adopted by the International Maritime Organization (IMO), the London (Dumping) Convention of 1972 and its 1996 Protocol, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants, and the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands of International Importance.

Relevant non-binding instruments that apply to the Arctic include the Declaration of Principles and Agenda 21 adopted by the 1992 UN Conference on Environment and Development in Rio de Janeiro, the Global Programme of Action for the Protection of the Marine Environment from Land-based Activities, and the 2002 World Summit on Sustainable Development and its Johannesburg Plan of Implementation. Some regional conventions also are relevant, including the Convention on the Protection of the North-East Atlantic and the Convention on Future Multilateral Co-operation in the North East Atlantic Fisheries, both of which extend into the Arctic region.

Patrick Kelley, U.S. Coast Guard

U.S. and Canadian Coast Guard ships take part in a cooperative survey to help define the Arctic continental shelf.

In addition, there are Arctic-specific frameworks. In 1991, the eight Arctic countries established the Arctic Environmental Protection Strategy (AEPS) to jointly deal with monitoring and assessment of contaminants, protection of the marine environment, emergency preparedness and response, and conservation of flora and fauna. Although criticized for failing to establish legally binding regulations, the strategy provided for joint cooperation on environmental issues and was very significant politically in the wake of the Cold War. In 1996, the AEPS came under the aegis of the newly established Arctic Council, an intergovernmental forum comprising the eight Arctic countries and including three indigenous organizations (later expanding to six) as Permanent Participants. The Arctic Council was mandated to address issues of sustainable development and environmental cooperation in the region.

The Arctic Council’s six working groups have produced exemplary scientific reports on Arctic environmental matters, including the ACIA, the Arctic Biodiversity Assessment and monitoring program, an Arctic Ocean Review that identifies how management of the Arctic marine environment can be strengthened, and the Arctic Marine Shipping Assessment.

The Arctic Council does not have a legal character, and, as such, its recommendations are not legally binding, leading to criticism that it is ineffective. The Council’s eight member countries, however, recently have begun negotiating legally binding agreements under its auspices. The first, in 2011, focused on search and rescue. The second, in 2013, addressed cooperation on marine oil pollution, preparedness, and response in the Arctic. It is widely expected that the eight countries will sign additional agreements in 2015, on preventing oil pollution and reducing black carbon and methane emissions, respectively.

That said, the rapidly changing Arctic does demand new governance processes to effectively manage and protect the region’s particularly sensitive ecosystem. Many such arrangements are in development. Most prominently, the IMO has been negotiating a mandatory international code of safety for ships operating in polar waters (the Polar Code), to cover the full range of design, construction, equipment, operational, training, search-and-rescue, and environmental protection matters for ships operating in the polar regions. New environmental measures that will come into force once the Polar Code is ratified, likely in 2017, will ban both garbage dumping and oily discharges from ships in polar waters, despite protests from Russia that this would compromise development of the Northern Sea Route. In addition, new voyage-planning regulations will oblige ships to consider whale migration corridors and feeding and breeding areas.

Work is also being done on fish stock management, with the five countries with Arctic Ocean coastlines agreeing in February 2014 to work toward an agreement to block commercial fishing in the ocean’s central portion, following the precautionary principle, until more is known about fish populations in the area. No commercial fisheries have operated in the area thus far. Current regional fisheries management organizations that have been established in the marginal seas of the Arctic Ocean include the Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organization and the North-East Atlantic Fisheries Commission.

Elsewhere in the Arctic, the United States signed a precautionary fisheries management plan in 2009 that prohibited commercial fishing on its side of the Beaufort Sea until scientific research and management measures can ensure a sustainable catch. And Canada announced in October 2014 the establishment of a Beaufort Sea Integrated Fisheries Management Framework for its side. The United States and Russia also signed a bilateral agreement in 1988 addressing fisheries management in the Bering Sea and the North Pacific, although regulation in that region could be more robust.

The next obvious candidate for a legally binding agreement to manage the Arctic region is a Regional Seas Agreement (RSA), which could provide the necessary framework for more consistent and holistic management of the Arctic Ocean. Much of the groundwork toward such an agreement has already been done by Arctic Council working groups, in particular the group on Protection of the Arctic Marine Environment. Admiral Robert Papp, the recently appointed U.S. Special Representative to the Arctic, openly suggested at a conference in Washington, D.C., in September 2014 that the United States would seek to advance an RSA management model while it holds the chairmanship of the Arctic Council in 2015–17.15

Economic Opportunities of a Warming Arctic

At least part of the reason that environmentalists and climate advocates have focused on the Arctic region is the unsettling prospect that Arctic warming, which has occurred largely as a result of the burning of fossil fuels worldwide, could result in the exploitation of additional, newly accessible, fossil fuels. This situation has been termed the “Arctic Paradox.” Drilling for oil in the Arctic is an almost universally detested concept, probably made worse by the high profile of the Exxon Valdez oil spill in Alaska in 1989.

Yet the portrayal of the Arctic as undergoing a “scramble” or “race” for resource exploitation is almost entirely overblown. Even today, the Arctic remains an extremely expensive arena to operate in: it is high-cost and high-risk. A reduction in sea ice may make some parts of the region more accessible, but it also will increase the amount of unpredictable ice floes. And the perpetually dark winters mean that the sea ice will always return for 6–10 months of the year. Costs of construction, maintenance, labor, and exportation of goods are higher in the Arctic than almost anywhere else, and the necessary precautions addressing safety and spill prevention add more costs. There are very high regulatory burdens in the region.

A handful of ambitious companies has explored Arctic waters, but with little success. Shell has spent eight years and $6 billion exploring in the Alaskan Arctic, but this effort has been plagued by a series of setbacks, prompting ConocoPhillips and Statoil to suspend their Alaskan Arctic drilling plans. Cairn Energy has spent $1.9 billion drilling eight test wells off the northwest coast of Greenland, but the company announced in January 2014 that it would not conduct further drilling operations that year. Meanwhile, operations in the Shtokman field off the coast of northern Norway and northwestern Russia have been suspended indefinitely due to low gas prices resulting from the global shale gas glut, despite capital costs estimated at $15–$20 billion absorbed by investors from Gazprom, Total, and Statoil. All of these serve as warning signs, preventing new investments in Arctic oil drilling in the short and medium term.16

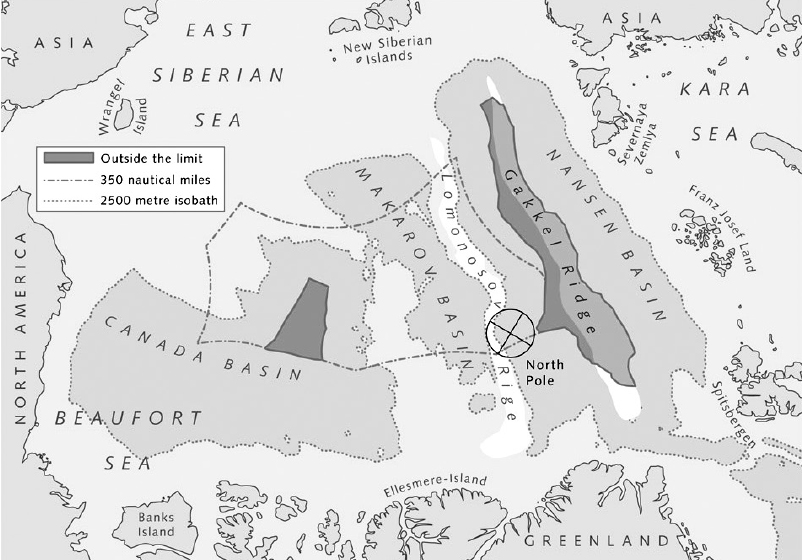

James Brooks

The oil drilling ship Noble Discoverer docked in Seattle before traveling to Alaska for the Arctic summer drilling season, 2012.

In the meantime, it is worth asking whether a ban on oil drilling would be ethical or even legal. Northern populations are sparse, workers are generally unskilled, and distances to markets are great. The best—and perhaps only—opportunity that northern communities have for development is resource exploitation, whether mining, fishing, or hydrocarbons. Southern activists inevitably conjure up the Shells of the world when they think about Arctic economic development, but for many communities and governments, poverty reduction is foremost in their minds.

Consider the case of Greenland, which for decades has sought greater independence from its former colonial master, Denmark, and has succeeded in obtaining a significant measure of self-determination. But Greenland will continue to depend on Denmark for an approximately $640 million annual subsidy for its 58,000 residents until it can replace these funds with an equivalent source—namely, resource revenues. In that sense, those who advocate for a ban on oil drilling in the Arctic are condemning Greenlandic Inuit to continued dependence on a European nation, or at the very least removing the ability of Greenlanders to decide for themselves if the environmental costs of drilling are worth the social and economic benefit. The right to weigh environmental, economic, and social costs when making governance decisions is enjoyed by all other sovereign nations and should not be expected to be relinquished by Arctic states and peoples to address the consequences of actions committed elsewhere.

Social and Economic Sustainability of the Arctic

It is important to recall that sustainability is not merely an environmental concern. As the Brundtland Report, Our Common Future, famously articulated in 1987, “Sustainable development must meet the needs of the present . . . in particular the needs of the world’s poor to which overriding priority should be given. . . . The satisfaction of human needs and aspirations is the major objective of development.”17

Incredible progress has been made in the circumpolar north to restore self-determination to northerners and in particular to indigenous peoples who may have very different values and goals than those found in the political centers of the eight Arctic countries. Setting a context in which local groups can be partners in resource development (or have the right to limit such development within their territory), and can make cost-benefit analyses of the jobs and public revenues that such development brings, has been a great political achievement of the past 40 years. Seeing the Arctic exclusively as an ecosystem in need of preservation—and not as a homeland where people have a right to live and work and improve their standard of living through economic development—imposes a hidden threat to the long-term sustainability of the region by removing the ability of northerners to make decisions about their lands and territories.

This does not mean that development should, or will, happen at any cost. It means that we should be careful about applying a standard of environmental protection in other regions that we would not accept in our own. Perhaps where international advocacy is needed is in those northern regions where local inhabitants do not have a say in how development proceeds. Support should go toward advancing local agendas in the north, not leveraging them to advance agendas in the south.

Conclusion

There is no doubt that the Arctic is undergoing significant and potentially devastating changes as a result of climate change. The seriousness of these changes should compel governments and individuals to act. Unfortunately, much of the recent focus in mitigating climate change is centered on the Arctic itself, despite the fact that the people living there are responsible for only a miniscule share of the human-caused greenhouse gas emissions that have precipitated climatic changes in the first place. Many southern environmentalists erroneously conflate Arctic impacts with Arctic activities, and develop their strategies accordingly. It would be far more constructive for them to work on reducing fossil fuel use in their own regions, rather than seeking to manage the consequences of this energy use in others.

For their part, the governments of the eight Arctic countries have made impressive and discernible advances in protecting the Arctic environment in the context of rapid change, including by addressing the impacts of externally induced climate change through the Arctic Council. Critics may rightly point out that the Council’s actions are not legally binding, that it is often under-resourced, and that it takes a long time to make decisions. But that is only compared to the ideal. When compared to any other regional or international intergovernmental forum, the Arctic Council is as progressive, action-oriented, and efficient as they come. This is made all the more impressive by the fact that this body includes both Russia and the United States, countries that are ideologically at odds on many issues.

From a northern perspective, climate change is having real consequences for traditional ways of life, food systems, infrastructure, and external relations. Indigenous peoples and other northerners have the greatest stake in protecting the Arctic environment—their home. As such, it is unconscionable for southern activists to attempt to deny Arctic peoples their right to make decisions on the region’s governance by calling for global bans or conservation areas to reduce economic activity that might contribute to climate change, when no other society in the world has accepted such restrictions. The eight Arctic countries should certainly do more to reduce their carbon emissions, but it is far from obvious that the Arctic Council is the best forum in which to do so. International, rather than regional, frameworks—beginning with the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change—are much better placed to discuss and negotiate carbon reductions, which then must be implemented at a national level.

Despite the fact that the Arctic region is not the source of global climate change, it has become necessary to address the consequences of global warming there. Arctic political actors have responded in kind. We would do well if the other political regions on the planet made as much effort to mitigate and adapt to climate change as the Arctic has, and we should focus our efforts accordingly.

![]()

* The Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf made its recommendations on the Norwegian submission in 2009. Canada has yet to submit a full submission but has indicated that it will claim the area up to and including the North Pole. Denmark made its submission on December 15, 2014, and Russia is awaiting recommendations on resubmitting its incomplete 2001 submission. The United States is not party to the UN Law of the Sea Convention (UNCLOS).

* Although the United States is not party to UNCLOS, it generally abides by the principles of the Law of the Sea, most of which is customary international law.