Discounted cash flow (DCF) and net present value (NPV)

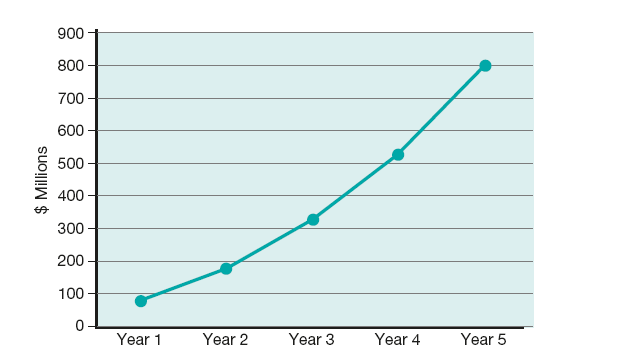

Discounted cash flow (DCF) is a method to assess and compare the current and future values of an asset. DCFs are calculated to assess the future cash flows that could come from an investment opportunity. A DCF analysis is a valuation method used to estimate the attractiveness of an investment opportunity. The total incremental stream of future cash flows from a capital project is tested to assess the return it delivers to the investor. If this return exceeds the required, or hurdle, rate, the project is recommended on financial terms, and vice versa. The DCF analysis discounts the future cash flows to their present-day value. Using future free cash flow projections and discounting them to a present value, the potential for investment can be evaluated. If the value arrived at is higher than the current cost of the investment, the opportunity may be a good one. DCF also converts future earnings into today’s money. Often these analyses are called net present value (NPV) calculations: determining today’s (present) value of tomorrow’s earnings (Figure 27.1).

Discounted cash flow (and NPV) is used for capital budgeting or investment decisions to determine:

A relevant cost is an expected future cost that will differ from alternatives. The DCF method is an approach to valuation, whereby projected future cash flows are discounted at an interest rate that reflects the perceived risk of the cash flows. The interest rate reflects the time value of money (investors could have invested in other opportunities) and a risk premium.

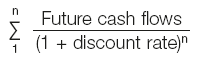

The discounted cash flow can be calculated by projecting all future cash flows and making a calculated assumption on what the current value of that future cash flow is according to the following formula:

The discount rate can be determined based on the risk-free rate plus a risk premium. Based on the economic principle that money loses value over time (time value of money), meaning that every investor would prefer to receive their money today rather than tomorrow, a small premium is incorporated in the discount rate to give investors a small compensation for receiving their money not now, but in the future. This premium is the so-called risk-free rate.

Next, a small compensation is incorporated against the risk that future cash flows may not eventually materialise, and that the investors will therefore not receive their money at all. This second compensation is the so-called risk premium and it should reflect the opportunity costs of the investors.

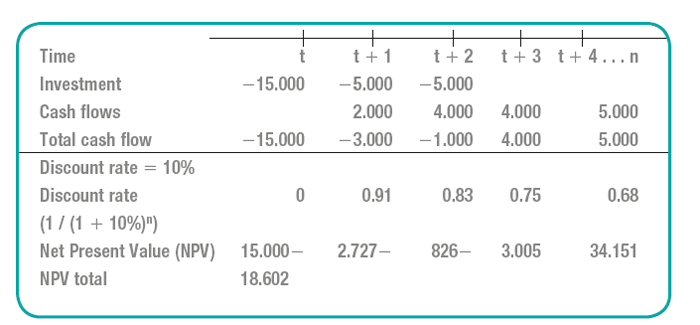

These two compensating factors, the risk-free rate and the risk premium, together determine the discount rate. With this discount rate, the future cash flow can be discounted to the present value. Based on the future cash flows and their present-day value, the DCF analysis can be used as basis for an NPV analysis. This NPV of a project or investment proposal can then be compared with other projects and proposals, allowing an investment decision to be made. A calculation example is presented in the following box:

First published in 1938 by John Burr Williams in a paper based on his PhD, ‘Discounted cash flow statements’, DCF analysis and NPV methods have become common all over the world.

DCF models are powerful, but they have their faults. DCF is merely a mechanical valuation tool, which makes it subject to the axiom ‘garbage in, garbage out’. Small changes in inputs can result in large changes in the value of a company. The discount rate is especially difficult to calculate. Future cash flows are also hard to forecast, especially if the largest part of the future cash inflows is received after 5 or 10 years. Also the discount rate and, more particularly, the risk premium are sometimes difficult to calculate objectively. Alternative calculation methods, such as weighted average cost of capital (WACC, see Chapter 29), have more sophisticated approaches to assess the expected return for investors.

Brealey, R.A. and Myers, S.C. (2003) Principles of Corporate Finance, 7th edition. London: McGraw-Hill.

Walsh, C. (2008) Key Management Ratios: the 100+ Ratios every Manager Needs to Know. Harlow: Pearson.

Willams, J.B. (1938) Theory of Investment Value, Cambridge: Harvard University Press.