11

Pathogens and Parasites

Kate S. Hutson and Kenneth D. Cain

11.1 Introduction

There is an enormous diversity of pathogens and parasites that can infect aquatic organisms. Pathogens, as described here are infectious organisms (viruses, bacteria, and fungi) that cause disease and will harm the host or cell. Parasites may be considered pathogens if they cause disease in a host species, but a parasite may live on or within a host for all or part of its life but not cause clinical disease. Conditions associated with intensive monoculture of aquatic animals mean that only a limited diversity of disease causing agents can successfully propagate, proliferate and harm aquaculture stock. Host specificity is arguably the most important property of a pathogen or parasite because it can determine whether it has the potential to become established in aquaculture, although there is potential for the emergence of new pathogens and parasitic diseases or for free‐living organisms to switch to a parasitic life style. Aquaculture systems and biosecurity practices impact pathogen and parasite diversity and virulence by either promoting exponential growth or possibly eliminating conditions necessary for some species to survive. Disease management strategies are most effective if host contact with pathogens can be avoided. However, in many aquaculture systems fish are naturally exposed to endemic pathogens and other strategies aimed at preventing disease (e.g., vaccination) or reactionary methods (i.e., treatments) are needed to minimise the effects of specific pathogens.

This chapter provides an introduction to the diversity of infectious biological agents commonly encountered when farming aquatic animals and highlights specific and broader impacts of each group. Specific case studies are developed for particularly harmful pathogens and parasites in aquatic fish and invertebrates. Current approaches to reducing infection intensities are outlined for each group and potential human diseases associated with the production of aquatic animals are also considered. Plants grown in aquaponics systems are subject to many of the same pests and diseases that affect food crops which have been well documented in other sources, thus strategies to disease management are highlighted herein. The World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) provides a current list of notifiable diseases (diseases that are required by law to be reported to government authorities) for molluscs, crustaceans and fish on their website and there are considerable economic costs attributable to a range of key parasites and pathogens in the world’s major marine and brackish water aquaculture production industries (e.g., Shinn et al., 2015). There are several text books dedicated specifically to aquatic animal diseases and disorders where further information can be sourced.

11.2 Viruses

Viruses are small particles that are infectious and require a host cell to replicate. Virus particles are referred to as virions and are made up of either DNA or RNA surrounded by a protein coat or capsid that provides protection for this genetic material. In some cases, viruses may be enveloped; meaning the virion has a lipid envelope usually acquired from the host cell membrane as it replicates and buds from the cell to form a new virus particle. Virus shapes can be complex and range from simple helical forms to icosahedral shapes. Most viruses can only be observed using electron microscopy. If special stains and markers are used, it is possible to visualise virally infected cells using light microscopy, but virus particles themselves are too small for this. To diagnose or detect viruses, they must be detected in tissue culture by infecting cell types (cell lines) they are able to replicate in. These cell lines are grown in the laboratory in nutrient media and when a sample is applied that contains a virus, the diagnostician will observe cell destruction and lysis under the microscope. This is usually referred to as cytopathic effect (CPE) of the virus. Viruses can infect many organisms and a range of cell lines have been developed from plants, insects, mammals, and fish. Some viruses (i.e., bacteriophages) can even infect bacterial cells and may have specificity to particular types of bacteria.

In aquaculture, viruses can spread through specific vectors (e.g., blood‐sucking parasites), via the faecal–oral route, physical contact and/or entering the body from food or water. Viral infections in animals may elicit an immune response that can eliminate the infecting virus. However, some viruses are effective at evading the host’s immune system and may even utilise part of the host cell to form a viral envelope as they replicate and bud from a cell. This makes it difficult for the host to recognise the virus particle as foreign and mount an immune response to neutralise it. Vaccines have been developed for a few select viral diseases that impact aquaculture, but their use is not currently widespread. Those that are available typically consist of a non‐virulent or killed virus, or some component of the virus of interest (e.g., protein or DNA) that is delivered to the animal by injection, immersion, or orally in the feed. Following a period of time (often temperature dependent) the host’s immune system responds to the viral ‘antigens’ and confers a level of acquired immunity that will result in the production of antibodies to the virus. These antibodies then provide specific protection and neutralization of the target viral pathogen if the animal comes into contact at a later time.

Viral pathogens are a significant challenge for aquaculture and can be devastating in hatcheries or when outbreaks occur at grow out sites. For most viral diseases, there are limited control or prevention options available. There have been hundreds of different viruses isolated from infected fish, but only a small percentage cause significant impact to aquaculture or are considered to be of regulatory significance and notifiable disease agents as designated by the OIE. As both freshwater and marine aquaculture expands globally, there are greater opportunities for the transmission and spread of aquatic viruses, and viral diseases will continue to cause substantial impact on aquaculture production. New and emerging viral pathogens impacting aquaculture are continually being discovered. One example is the recent discovery of tilapia lake virus (TiLV) found to be the cause of significant mortality in tilapia farms in Israel and Ecuador. In this chapter, we present a range of viral groups and specific viral agents that affect cultured as well as wild fish. Shrimp and prawn culture have also been heavily impacted by viral diseases (see sections 10.5.2.1 and 22.10). For example, white spot syndrome virus (WSSV) has decimated shrimp production in many regions due to its rapid spread and heavy mortality. It is important to note that not all viral groups and families are represented here and only a fraction of the many viral pathogens that impact aquaculture is described in this chapter. There are many books and reviews available that provide in depth coverage of these and other important viral pathogens of fish, crustaceans and molluscs.

11.2.1 Betanodaviruses

The genus Betanodavirus is in the family Nodaviridae. Viruses in this genus are linked to disease outbreaks in wild and cultured fish species, while the other genus in this family Alphanodavirus causes disease in insects. Many different species of marine and freshwater fish are susceptible to infection with Betanodaviruses and the disease is most commonly referred to as Viral Nervous Necrosis (VNN), but it is now recognised and has been renamed viral encephalopathy and retinopathy (VER) by OIE. This VER virus has been isolated from fish on all continents except South America; however, there has been one report on the identification of nodavirus positive samples from the brains of two freshwater aquarium species imported to South Korea from the Amazon. Nodavirus infections appear to be highly prevalent in areas where marine fish culture is widespread and have been linked to severe disease outbreaks primarily in larval and juvenile marine as well as freshwater fish. In Australia, VER was first detected in barramundi, and the virus has been isolated from over 40 species globally (Colorni and Diamant, 2014).

Nervous Necrosis Virus (NNV) species are small (25–30 nm) single stranded RNA viruses that are non‐enveloped and possess an icosahedral capsid (Colorni and Diamant, 2014). An important aspect of nodavirus infections is that they are transmitted vertically (from adults to their offspring) and horizontally (among individuals). It is likely that infected broodstock transmit VER virus to progeny during spawning or rearing. Clinical signs vary but the virus is known to affect nervous tissues and can cause erratic swimming, whirling, loss of equilibrium, and blindness; possibly due to its affinity for retinal tissue, which is a primary site of viral replication (Colorni and Diamant, 2014). Because surviving fish often become asymptomatic carriers and the virus impacts larval and juvenile fish, biosecurity is important. Outbreaks have been reported in European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) in the 1990s, and the first report of VER virus in North America occurred in juvenile California white sea bass (Atractoscion nobilis) being cultured for population recovery efforts. Control measures for VER are limited and no commercial vaccine is available. Because fish that survive outbreaks can become carriers, the best method to reduce impacts from VER is to eliminate its presence through strict biosecurity and sanitation measures. Infected fish may need to be culled from the population and new fish should be quarantined and tested prior to mixing with the general population.

11.2.2 Birnaviruses

Viruses in the family Birnaviridae are non‐enveloped double‐stranded RNA (dsRNA) viruses with an icosahedral shape that infects fish and shellfish. The genus Aquabirnavirus comprises three species, the first being the type species Infectious Pancreatic Necrosis Virus (IPNV), the second being the marine aquabirnavirus (MABV) that infects yellowtail (Seriola quinqueradiata) and is referred to as yellowtail ascites virus (YAV), and the third being the Tellina virus (TV‐1) that was isolated from the marine mollusc Tellina tenuis. It should be noted that YAV has since been shown to infect a variety of marine hosts.

IPNV is one of the most significant finfish viruses in this family and causes the disease Infectious Pancreatic Necrosis (IPN). Although viral diseases were suspected in hatcheries in the early to mid‐1900s, it was not until the establishment of cell lines from specific fish species that IPNV and other fish viruses were identified. IPNV causes acute disease and is highly contagious, most often affecting very young salmonid fry. In some cases, mortality in the hatchery is up to 100% (Crane and Hyatt, 2011). IPNV is characterised as an aquatic birnavirus and since the time of its discovery similar IPN‐like viruses (often non‐virulent) have been found in many salmonid and non‐salmonid hosts in both fresh and sea water.

Interesting case reports have identified both non‐virulent forms of aquatic birnaviruses and virulent forms of IPNV that have impacted aquaculture facilities. In Australia, the first report of an aquatic birnavirus was from routine sampling of Atlantic salmon farms. This virus grew on a range of fish cell lines and reacted with commercial IPNV antisera; however, clinical disease associated with this was never observed and it was subsequently isolated from a range of other species in the marine environment. The first report of IPNV in Mexico came from a clinical outbreak in farmed rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) where gross and microscopic pathology was consistent with IPN. Further characterisation identified this as the Buhl strain of IPNV.

The contagious nature of IPNV has been problematic and fish that survive a disease outbreak often become asymptomatic carriers that are able to horizontally transmit IPNV without exhibiting clinical signs of disease. The best control strategy for IPN or any viral disease affecting finfish is to avoid contact through proper biosecurity. It is not always possible to avoid contact; therefore, other management options such as vaccination are available in some countries.

11.2.3 Herpesviruses

Two significant fish viruses in the order Herpesvirales and the family Alloherpesviridae are Channel Catfish Virus (CCV) and Koi Herpesvirus (KHV). These viruses are highly contagious. CCV and KHV have resulted in substantial economic impact to the US catfish aquaculture industry and ornamental koi producers, respectively.

CCV is considered endemic in the USA and channel catfish virus disease (CCVD) emerged as a problem during the early years of commercial catfish farming. In the 1960s high mortalities in channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus) were reported primarily in fry and fingerlings following introduction of fish from the hatchery to the fry ponds and in 1971, CCV was identified as a herpes virus. It is now present in nearly all regions in the US that produce catfish. There are no prevention or treatment options for CCVD, but there have been attempts to develop vaccines to CCVD. It was shown that a DNA vaccine could provide protection against CCVD; however, the use of this under practical conditions is limited by the need for injection delivery. In fish, CCV can persist in a carrier state and transmission of the virus is thought to be both vertical from the broodstock and horizontal through the water column. In catfish ponds, water temperature and other environmental stressors appear to play a role in disease occurrence and severity.

KHV (also known as cyprinid herpesvirus 3; CyHV‐3) has a more recent history compared to CCV as it was first reported in the UK in 1996. It has since been reported and confirmed in nearly all countries that produce koi or other common carp, except Australia and New Zealand. Interestingly, Australia is exploring the possibility that KHV could be used as a potential biological control agent against invasive common carp in areas where their populations have expanded. KHV is listed by OIE as a notifiable disease and this creates regulatory concern for aquaculture producers and koi growers. Once a fish becomes infected or survives KHV disease (KHVD) they are potential carriers of the virus.

There is no effective treatment for KHVD, however, an attenuated live vaccine was approved for the prevention of this disease. It has been shown to generate high antibody titres specific for KHV and to protect common carp or koi following challenge. One major issue is that import and export control regulations may not allow movement of KHV‐vaccinated fish. This relates to the live nature of the vaccine and the inability of diagnostic tests to differentiate between naturally infected or vaccinated fish. For the koi hobbyist or carp producer it is important to maintain strict biosecurity and prevent exposure of fish to KHV.

11.2.4 Iridoviruses

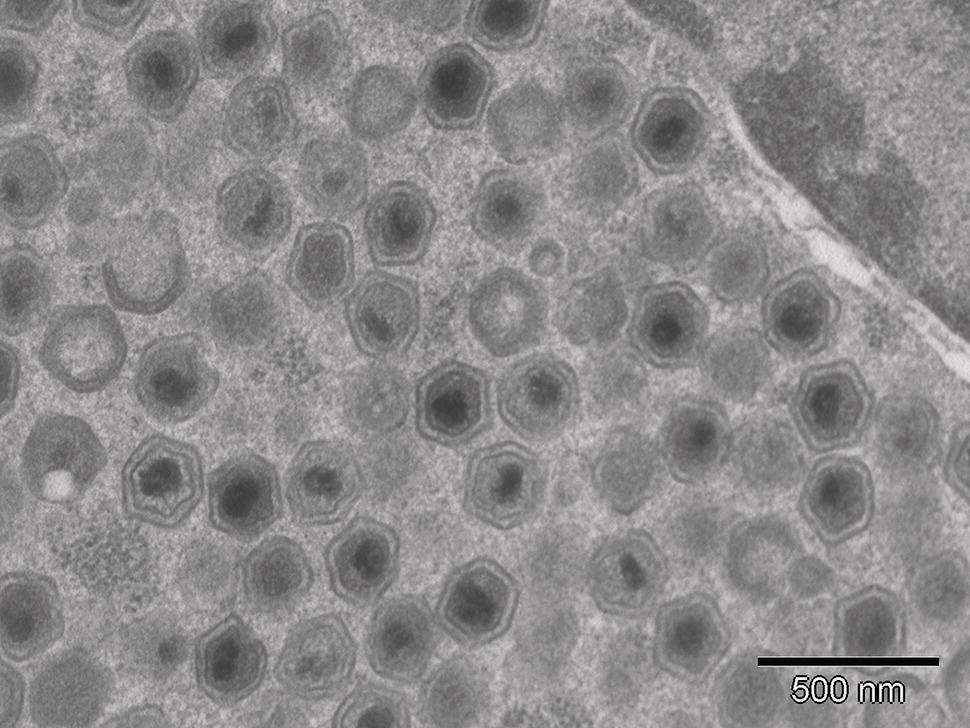

There are a number of viruses in the family iridoviridae that infect fish. A brief overview of the more significant species is provided here, but a critical review of fish iridoviruses is available in the literature (Whittington et al., 2010). Fish iridoviruses fall into three genera within this family, Megalocytivirus, Ranavirus, and Lymphocystivirus. There are also fish iridoviruses that are yet to be assigned to a genus, such as white sturgeon iridovirus (WSIV) and Erythrocytic necrosis virus (Whittington et al., 2010). Iridoviruses are icosahedral in shape (Figure 11.1), large in structure (120–300 nm) and may appear enveloped or non‐enveloped in some cases. They consist of a genome of double‐stranded DNA that is methylated in a way similar to viruses affecting vertebrates.

Figure 11.1 Electron micrograph of white sturgeon, Acipenser transmontanus, iridovirus (WSIV) particles showing the characteristic icosahedral shape.

Source: Reproduced with permission from Dr J. Drennan, Colorado Parks & Wildlife.

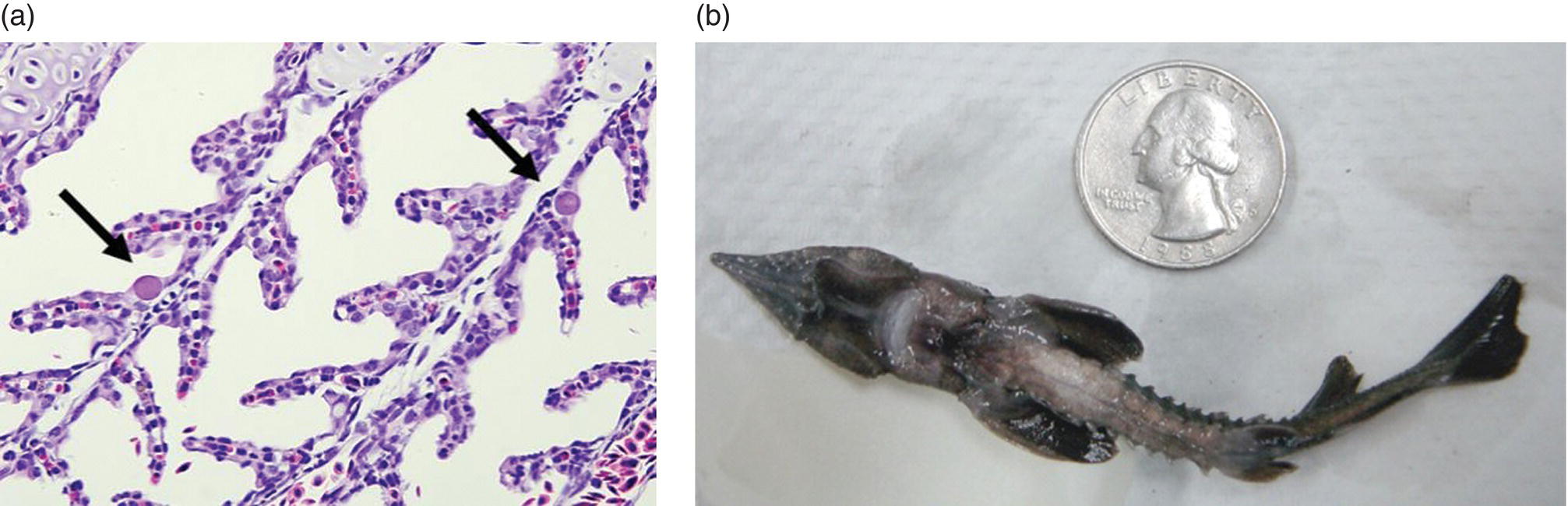

In general, ranaviruses and megalocytiviruses are important emerging pathogens for cultured and wild fish and affect fish in both marine and freshwater environments. Lymphocystis virus disease (LVD) affects fibroblastic cells in the skin and connective tissue resulting in superficial lesions on fish. LVD is known to affect more than 125 wild and cultured fish species in marine and freshwater and is widespread in distribution. Transmission is horizontal and incidence rates for this disease may be as high as 70%. It has been speculated that another iridovirus (WSIV) may be transmitted vertically as disease outbreaks have been observed in progeny from adult white sturgeon (Acipenser transmontanus) collected from the wild and spawned for conservation or commercial aquaculture programs. The potential that WSIV could be transmitted vertically was investigated following collection and disinfection of gametes from wild caught sturgeon. Vertical transmission did not occur but progeny from eggs incubated using a river water source all became infected. This and further cohabitation experiments clearly showed that WSIV was horizontally transmitted and highly contagious. WSIV does not cause a systemic infection and appears to be primarily localised to the epidermis of the skin, barbells, oropharynx, and gills of sturgeon. Although clinical signs vary, and limited pathology or tissue distribution is observed, haemorrhaging can occur, and mortality may be high in heavily infected fish due to secondary bacterial infection or possibly a wasting syndrome resulting in emaciation and eventual death (Figure 11.2).

Figure 11.2 (a) WSIV infected cells in the gill lamellae of white sturgeon. Arrows indicate infected cells; and (b) juvenile white sturgeon with signs of emaciation due to lack of food intake following infection with WSIV.

Source: Reproduced with permission from Dr J. Drennan, Colorado Parks & Wildlife.

Epizootic haematopoietic necrosis virus (EHNV) was isolated in 1985 in Australia and represents the first iridovirus known to cause systemic infection and high mortality in finfish. It appears to be restricted to Australia, where large mortality events in wild redfin perch (Perca fluviatilis) and severe outbreaks in farmed rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) have been reported. Due to its virulence and localization, the disease epizootic heamatopoietic necrosis (EHN) is notifiable to OIE. In general, redfin perch are highly susceptible and considered to be important carriers of the virus; however, occurrence of mortality in farmed rainbow trout highlights the potential risk should this virus spread outside endemic areas.

11.2.5 Orthomyxoviruses

Viruses in the family Orthomixoviridae consist of six genera. They include Influenza Virus A, B, and C, which infect humans, other mammals, and birds; Isavirus, which infects salmon; Thogotovirus, infecting insects and mammals, including humans; and Quaranjavirus, a new genus primarily infecting arthropods and birds. Infectious salmon anaemia virus (ISAV) is an orthomyxovirus in this family and considered the type virus in the Isavirus genus. ISAV is the causative agent of infectious salmon anaemia (ISA), a disease of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). This disease that initially affected farmed Atlantic salmon in Norway, causes a systemic condition resulting in severe anaemia in fish and is often linked to necrosis and haemorrhaging of internal organs. An outbreak may result in high cumulative mortality over time, but the disease may be more chronic in nature with low level daily mortality of 0.05–0.1%. ISA is considered a major disease impacting Atlantic salmon aquaculture and has been isolated from fish in Eastern Canada, the UK, Faroe Islands, and Chile. There are also reports of ISAV being discovered in tissues of farmed Atlantic salmon from the coast of British Columbia, Canada; however, only sequences from the highly polymorphic region (HPR) of ISAV variants have been identified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and to date ISAV has not been isolated in tissue culture. The lack of disease outbreaks and limitations in interpreting positive results from molecular detection methods brings into question the presence of this virus in this region. It is clear that identification of ISAV in British Columbia salmon farms would be particularly concerning since other salmonids including Pacific salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) can become infected. However, at this time, it does not appear that clinical disease develops in species other than Atlantic salmon, but it can be speculated that virulent strains of ISAV could emerge in Pacific salmon species if it were to persist in a carrier state.

Following infection from ISAV, fish have been shown to be resistant to re‐infection and develop a protective immune response. This has led to research on vaccine development and although the efficacy of such vaccines is not completely clear, there are vaccines available and these have been used in North America.

11.2.6 Rhabdoviruses

Within the family Rhabdoviridae there are six genera; however, those that infect fish are primarily from the genus Novirhabdovirus. Viruses in this genus are generally well characterised and infectious haematopoietic necrosis virus (IHNV) is the type species. Other fish rhabdoviruses were tentatively placed in the genus Vesiculovirus, but two new genera have been recently proposed as rhabdoviruses that are not congruent with Novirhabdovirus (Kurath, 2012). These include Sprivivirus of which spring viremia of carp virus (SVCV) is the type strain, and Perhavirus of which perch rhabdovirus is the type species. Rhabdoviruses of fish infect a broad range of host species and may have broad geographical distribution, including freshwater and sea water environments. Some of the most severe and contagious viruses impacting aquaculture and wild fish fall within this family. New fish rhabdoviruses continue to be discovered and due to their significance, there is continual work in the areas of diagnostics and development of new and better control/prevention methods.

Rhabdoviruses that infect fish are usually bullet‐shaped enveloped viruses with virions typically measuring approximately 75 nm wide and 180 nm long, replicate in the cytoplasm of cells and contain single‐stranded RNA encoding five to six proteins. Some rhabdoviruses are of particular concern in wild and cultured fish, cause diseases that are considered notifiable by OIE, and include SVCV, IHNV, and viral haemorrhagic septicaemia virus (VHSV). Of these, IHNV and VHSV have been extensively characterised and many sources are available in the literature that provide comprehensive descriptions and reviews (Kurath, 2012).

IHNV causes infectious haematopoietic necrosis (IHN) and was originally described following disease outbreaks in Sockeye (Oncorhynchus nerka) and Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytsch) in the Pacific northwest USA in the 1950s. It has since been a significant concern in freshwater salmonid aquaculture (Figure 11.3) but can infect fish in both fresh and sea water environments. Outbreaks have occurred in Atlantic salmon farms in Canada, but IHN remains a primary concern for wild fish or hatchery‐reared Pacific salmon in North America as well as commercial rainbow trout farms in the USA and elsewhere. Originally considered a viral disease restricted to North America, it has since spread to European and Asian countries where salmonids are cultured. This disease affects young salmonids and an acute outbreak can result in mortalities up to 100%; however, most outbreaks are less severe and surviving fish may develop immunity to re‐infection. The best way to manage around IHN is to avoid contact but in areas where it is endemic this can be difficult. As with most diseases in fish, environment and stress during culture can impact the severity of an outbreak. Five genogroups are known to exist for IHNV and these have been linked to outbreak severity in different host species. The ability of fish to develop immunity to IHNV is well documented and research in the area of vaccine development has been substantial. The most effective vaccines against IHN are DNA vaccines that must be injected into fish. The first commercial DNA vaccine was developed and licensed by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) in 2005 and is available as a plasmid DNA‐based vaccine (Apex®‐IHN).

Figure 11.3 Severe exophthalmia in rainbow trout fry infected with IHNV.

Source: Reproduced with permission from G. Kurath.

Another important fish rhabdovirus is VHSV. This virus causes viral haemorrhagic septicaemia (VHS), considered the greatest disease problem in the European trout farming industry. This virus was originally thought to be restricted to Europe, but it is now clear that it has a broad host and geographic range and multiple strains of this virus have been described. In 1988 an interesting case occurred in Washington State where for the first time VHSV was discovered in returning adult Pacific salmon. This discovery and isolation of VHSV resulted in the compulsory euthanasia of millions of hatchery fish that where the progeny of infected adults. This occurred despite an actual disease outbreak and it was later found that this strain of VHSV was distinct from the European strain and appeared to be associated with a range of marine species such as herring (Clupea pallasii) and cod (Gadus macrocephalus). It is virulent to herring but unlike the European isolate it is avirulent in rainbow trout. In 2003, VHSV emerged in wild fish in the Laurentian Great Lakes in North America. Fish affected by VHS were dying in large numbers and washing up on shore in many areas. The number of fish and species affected was alarming with over 1823 cases and 19 fish species that tested positive for VHSV. This has led to further characterization of VHSV strains and now a series of four genogroups and additional subgroups exist, with the Great Lakes strain designated as genotype IVb.

11.3 Bacteria

Bacteria are categorised into a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. They are larger than viruses, are typically visualised using light microscopy, and may be rod‐shaped, spherical, or spiral‐shaped. Many bacteria are harmless or may even be beneficial to their host. They can be found in the environment, may be part of many animals' natural gut microbiota, or in some cases may invade an organism and cause disease. Bacterial disease outbreaks in aquaculture operations result in significant economic losses in both public (resource enhancement and stocking) and private sectors. In some cases, there are vaccines used to prevent bacterial disease outbreaks, and antibiotics delivered in feed have commonly been used to treat bacterial infections in fish and other animals. Such treatments have been important factors in disease management but represent risks due to the ability of bacteria to develop resistance to common antibiotic treatments. Infection to humans due to aquatic pathogens is relatively rare; however, bacteria are the most common aquatic pathogens found to cause zoonotic infections by transmission from fish or culture water to humans (see section 11.12).

In this section, an overview of select bacterial pathogens known to infect fish and cause significant economic impact for aquaculture is provided. It is not possible to cover all new and emerging bacterial pathogens of fish, crustaceans and shellfish here, but it should be noted that at this time there have been 13 genera of bacteria reported as pathogenic to aquatic animals. These include Gram‐negative pathogens such as Aeromonas, Edwardsiella, Flavobacterium, Francisella, Photobacterium, Piscirickettsia, Pseudomonas, Tenacibaculum, Vibrio and Yersinia; and Gram‐positive bacterial pathogens within the genera Lactococcus, Renibacterium and Streptococcus.

11.3.1 Aeromonas salmonicida

Furunculosis, caused by the Gram‐negative bacteria Aeromonas salmonicida was one of the earliest described fish diseases and was named due the formation of large boils (furuncles) just under the skin in clinically sick fish. First described in the late 1800s in cultured and wild fish in Europe, it is widely distributed and infects many salmonid and non‐salmonid species in marine and freshwater worldwide. Although the taxonomy of Aeromonas is not always agreed upon, there are four primary subspecies of A. salmonicida that are considered infectious. The ‘typical’ strain is considered A. salmonicida salmonicida primarily affecting salmonids, while the subspecies masoucida, achromogenes, and smithia are ‘atypical’ strains that affect salmonids, and A. salmonicida nova is an ‘atypical’ strain that is infectious for non‐salmonid fish.

Furunculosis is widely reported in commercial and ‘resource’ hatcheries in the USA that stock fish into public waters and is also known to impact wild fish. This disease became problematic in the Atlantic salmon industry due to outbreaks in smolts when they were moved from freshwater to seawater. When the disease affects young fish, mortality can be acute and clinical signs may be limited to darkening of fish, lethargy, and anorexia. The formation of haemorrhaged boils or furuncles may appear more often in fish that are chronically affected. If the furuncles rupture and release bacteria, toxins or necrotic cells, an increase in bacterial load can occur and thus an increase in the risk of horizontal transmission to other fish. As with other bacterial diseases of aquatic organisms, A. salmonicida is not considered by OIE as a notifiable disease; however, other regulatory agencies may restrict fish movement to non‐endemic areas (e.g., USA state or federal agencies acting under the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Aquatic Animal Health Program (FWS‐AAHP) Title 50 act).

Control of infection from A. salmonicida is most effective by preventing exposure. In areas where this pathogen is found in the environment, spring or ground water should be used as a water source for aquaculture facilities because they are typically free of most pathogens. If an open water source such as a river, lake, or marine environment is utilised then preventative measures such as vaccination should be incorporated if possible. Due to the long history of furunculosis, some of the earliest attempts at vaccinating fish were with A. salmonicida. Currently, there are a range of furunculosis vaccines commercially available. The use of these and other bacterial vaccines has nearly eliminated the need for antibiotic treatment in Norway’s Atlantic salmon industry. This is not the case everywhere and for some species and regions, antibiotic treatments are administered when fish show clinical signs of furunculosis. Due to the concerns over antibiotics, they should be used as a last resort.

11.3.2 Edwardsiella ictaluri

Enteric septicaemia of catfish (ESC) is caused by the Gram‐negative bacteria Edwardsiella ictaluri. This is considered one of the most severe bacterial diseases in the catfish industry in the USA and may account for 30% or greater losses. Cases of ESC are most often reported in the spring around May and June and also in autumn in September and October due to the bacterium’s preference for temperatures between 22 and 28 °C. In general, channel catfish (Ictaluri punctatus) are the primary species that is susceptible to ESC, but infection with E. ictaluri along with minor pathology has been reported in other species of catfish and non‐ictalurids. It has been a primary problem in the USA, but outbreaks, sometimes severe, have been reported in Australia, Indonesia, Japan, Thailand, and Vietnam.

Edwardsiella ictaluri infections can lead to acute or chronic forms of ESC. In the acute form the infection is systemic with bacteria moving into the blood stream. This causes septicaemia and results in ulcerations and necrosis in multiple organs. Haemorrhaging may appear around the mouth and operculum and along the base of the fins (Figure 11.4). Interestingly, in the chronic form, E. ictaluri may enter the olfactory organ or nasal passage and move into the skull and skin of the head to form a lesion, leading to a condition known as ‘hole in the head’.

Figure 11.4 Channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus) showing external clinical signs of haemorrhaging near the mouth and base of the fins following laboratory challenge with E. ictaluri.

Source: Reproduced with permission from Dr B. LaFrentz.

Control of ESC in commercial catfish operations has relied on antibiotic treatment, and such treatments continue to be used to control losses due to this disease. There is a commercial immersion vaccine consisting of a live‐attenuated strain of E. ictaluri available in the USA. The potential to prevent major impacts due to ESC through vaccination is high, but some practical difficulties exist because delivery of the vaccine to fish when they are fully immunocompetent is often not possible. Catfish production in many cases is on a large scale and ponds are often stocked shortly after the fry hatch, which is usually the only time fish are handled until harvest and therefore the only time a vaccine can be administered.

11.3.3 Flavobacterium psychrophilum

Bacterial coldwater disease (BCWD) and rainbow trout fry syndrome (RTFS) are caused by Flavobacterium psychrophilum. This bacterial pathogen and a number of other bacteria in the Flavobacteriaceae family can cause disease in cultured and wild fish. Flavobacterium psychrophilum is one of the best‐known pathogens in this genus (along with F. columnare) due to the significant impact BCWD has on salmonid aquaculture worldwide. Nearly all salmonids are susceptible to F. psychrophilum and it has been reported to cause disease in a number of non‐salmonid species as well. Young fish are primarily affected, but when early hatched fry are infected, mortality may be greater than 50%. Although considered ubiquitous in the aquatic environment, it appears that F. psychrophilum can be transmitted both horizontally and in some cases vertically from parent to progeny (Cain and Polinski, 2014). It has been isolated from salmonid eggs and egg contents, and it has been shown that F. psychrophilum could survive inside fertilised eggs following nano‐injection, which resulted in high mortality in eyed eggs and early hatched fry due to F. psychrophilum. Such findings make broodstock selection critical and highlight the potential for this bacterium to persist within a hatchery environment.

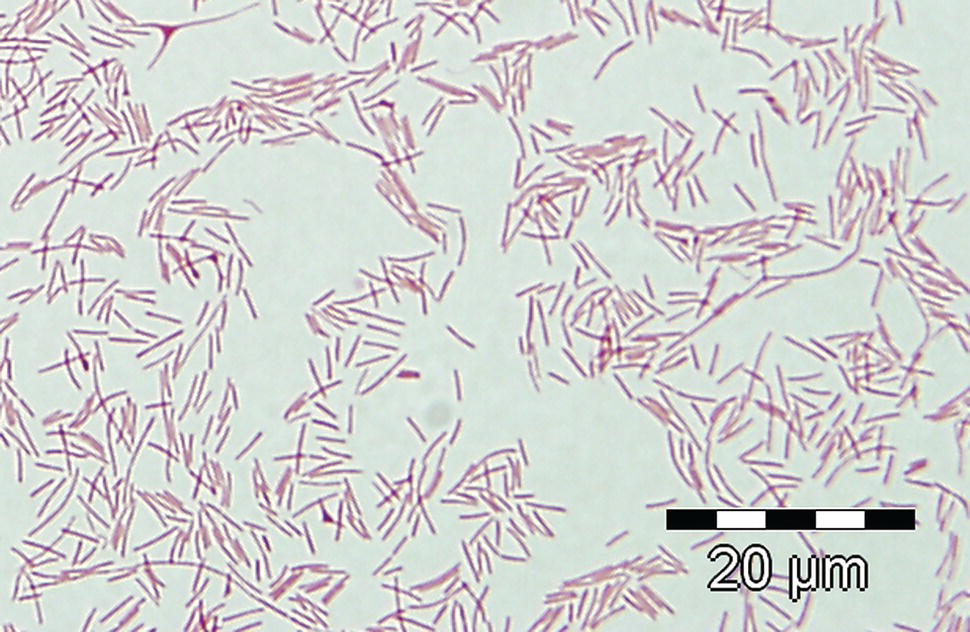

Flavobacterium psychrophilum is a Gram‐negative bacterium with cell morphology consistent with other Flavobacterium species. Although strain differences exist, most bacterial cells are rod shaped (Figure 11.5) and range in size from 0.2–0.75 × 2–7 μm. This bacterium has gliding motility and a gliding mobility protein (GldN) may affect the bacterium’s ability to enter and infect cells.

Figure 11.5 Light micrograph or Flavobacterium psychrophilum cells showing long thin rod‐shaped bacteria.

Source: Reproduced with permission from Dr B. LaFrentz.

Cases of BCWD and/or RTFS are widespread and include most salmonid producing countries. It is widespread in the USA and European trout industries, and F. psychrophilum has been reported in trout and other species in a number of countries, including Australia where it was reported in Atlantic salmon during the freshwater stages of production. There have been a large number of F. psychrophilum strains isolated and such strains can have varying levels of virulence. Although mortality may be high from BCWD or RTFS, commercial aquaculture also experiences losses due to growth and performance impacts as well as increased levels of deformities (resulting in a lower grade product) following an outbreak. In the USA, public hatcheries that rear steelhead (ocean run rainbow trout) and salmon for stocking purposes are also heavily impacted by BCWD, and this disease causes greater overall losses in these facilities than any other fish disease (Cain and Polinski, 2014).

Clinical signs of BCWD/RTFS will vary depending on the species and age of fish infected. There are acute forms of the disease that cause septicaemia and high mortality, but lingering chronic infections may also occur. Fish infected with F. psychrophilum exhibit behavioural changes such as spiral swimming or lack of feeding response. Internally, this bacterium has an affinity for the spleen but it can be isolated from many organs and tissues depending on the severity of infection. Externally, a range of clinical signs may appear including frayed fins, exophthalmia, dark pigmentation, or haemorrhages on the skin or bases of fins. In some cases, the caudal peduncle region may be severely eroded (Figure 11.6), which relates to this disease originally being referred to as ‘peduncle disease’.

Figure 11.6 Laboratory challenged rainbow trout showing severe erosion in the dorsal musculature at the site of Flavobacterium psychrophilum injection.

Source: Reproduced with permission from Dr B. LaFrentz.

Currently, control of BCWD/RTFS relies on good fish culture practices and antibiotic treatment following confirmation of an outbreak. However, there has been extensive work aimed at developing an effective vaccine to prevent and/or limit disease impacts. Due to the small size and the production requirements for species such as rainbow trout, the key to a successful vaccine has been creating one that can be mass delivered to very young fish. Recently, a live‐attenuated F. psychrophilum strain that provides protection following immersion vaccination has been developed. This shows great potential for commercial development, and more recent improvements in the formulation have improved efficacy in the laboratory and in the field. Other alternative control strategies may include the use of natural gut bacteria that can be incorporated into feed as probiotics. This has been shown to reduce mortality from BCWD following feeding of two bacterial strains (Enterobacter C6‐6 and C6‐8) isolated from the gut of healthy rainbow trout. Further work has demonstrated that reduced mortality is due to the expression of an anti‐microbial peptide by the Enterobacter.

11.3.4 Flavobacterium columnare

Flavobacterium columnare is the causative agent of columnaris and has historically been a major disease in warmwater aquaculture; however, columnaris is emerging as a significant problem in salmonid aquaculture with infections increasing in recent years. A wide range of species are affected by columnaris, and in the catfish industry, it has been estimated that infection by F. columnare resulted in mortality and 39% losses in 2009. Clinical disease occurs most often in young fish and transmission of this pathogen is considered horizontal. Good water quality is important as outbreaks can be linked to stress associated with poor environmental conditions. Temperature plays an important role in infection with occurrence in channel catfish being most prevalent at temperatures between 25–32 °C (Lio‐Po and Lim, 2014). In wild adult salmon in the Pacific northwest of the USA, columnaris has been an issue during migration from the ocean to spawning grounds since many of the reservoirs they must pass through have elevated water temperatures in spring and summer months.

Similar to other Flavobacteria, F. columnare is Gram‐negative and represented as a long rod‐shaped bacterium. One characteristic that gives columnaris its name relates to the tendency of these bacteria to form ‘hay stacks’ or columns in wet mounts of the gills or other infected tissues (Figure 11.7). Clinical signs of disease often include frayed fins, skin lesions that may appear yellowish in colour or in some cases depigmented (Figure 11.8), or gill damage due to colonisation of bacteria (Figure 11.9). It has been suggested that acute mortality results more often when F. columnare is associated with the gills (Lio‐Po and Lim, 2014), but infections can become systemic and result in high mortalities and in some cases minimal pathology to infected organs. To prevent or control columnaris, it is critical to maintain fish in optimal conditions. Should an outbreak occur and represent primarily a systemic infection, then antibiotic treatment with medicated feed may be beneficial. External and gill associated infections may require application of chemical therapeutants, such as potassium permanganate to the water (Lio‐Po and Lim, 2014). Currently, in the USA there is a commercially available vaccine aimed at prevention of columnaris in channel catfish; however, it is not clear how widespread its use is or if this live‐attenuated vaccine is efficacious in other fish species.

Figure 11.7 Columns or ‘hay stacks’ formed by Flavobacterium columnare visible in a wet mount of infected gill tissue.

Source: Reproduced with permission from Dr A. E. Goodwin.

Figure 11.8 Depigmented lesions following laboratory challenge of tilapia Oreochromis sp. with Flavobacterium columnare.

Source: Reproduced with permission from Dr B. LaFrentz.

Figure 11.9 Gill necrosis following laboratory challenge of rainbow trout with Flavobacterium columnare.

Source: Reproduced with permission from Dr B. LaFrentz.

11.3.5 Piscirickettsia salmonis

Salmonid rickettsial septicaemia (piscirickettsiosis) caused by the intracellular Gram‐negative bacteria Piscirickettsia salmonis is a disease that impacts fish primarily in seawater. It infects salmonids and was first reported in coho salmon in Chile. This disease has had the greatest impact on salmonid aquaculture in Chile, but P. salmonis has been found in a number of countries including Europe, North America, and Australia, where a rickettsia‐like organism was isolated in Tasmania. In Chile, cases resulting in up to 90% mortality of coho salmon were reported in the 1980s with clinical disease occurring between 6–8 weeks post transfer to seawater cages. Transmission of P. salmonis appears to be primarily horizontal, but it has been suggested that vertical transmission can occur.

The intracellular nature of P. salmonis makes isolation and confirmation of disease more difficult. Typically, piscirickettsiosis is diagnosed following histological examination and immunohistochemistry of cells infected with P. salmonis. However, it can be isolated using fish cell lines in a similar manner to virus isolations. Cytopathic effect due to P. salmonis is evident on CHSE‐214 cells when incubated for up to two weeks at temperatures of 15–18 °C. Other serological and molecular methods such as PCR are available to confirm infection.

Fish that are affected by P. salmonis may be lethargic, go off feed, become dark in colour, and have pale gills. Internally, the posterior kidney and spleen may be enlarged, and the liver may develop nodules that if ruptured will result in crater‐like lesions. In some species, the nervous system can be affected, and fish will swim in an irregular manner.

Prevention and control options for piscirickettsiosis have been limited in the past and the use of antibiotics appears to have been less successful due to the intracellular nature of P. salmonis. Vaccination has shown promise and commercial vaccines have recently become available. Although the efficacy of these vaccines is still in question, it is clear that prevention of an outbreak through methods such as vaccination offer the best opportunity to manage this disease in aquaculture. Good management practices including low density stocking of pens and removal of mortalities early in an outbreak are important. Other considerations include potential screening of broodstock and rejection of eggs from fish that are positive for infection.

11.3.6 Vibrio spp.

Vibriosis is caused by a number of bacterial species in the family vibrionaceae and affects both coldwater and some warmwater species of fish, crustaceans and molluscs in marine or brackish water. It should be noted that many species of Vibrio cause disease in aquatic organisms, but the focus here will be primarily on the most common species causing vibriosis and include Vibro anguillarum (also referred to as Listonella anguillarum), V. ordalii, and V. salmonicida (also referred to as Aliivibrio salmonicida). Vibrio anguillarum had major economic impacts on salmonid aquaculture prior to the implementation of commercial vaccines, which can be highly effective against vibriosis. Mortality in Atlantic cod (G. morhua) aquaculture has also been reported due to V. anguillarum, and early reports from Chile indicated outbreaks with moderate mortality of up to 8% due to V. ordalii. Vibrio salmonicida has been shown to accumulate rapidly in the blood and colonise the intestine, which is thought to result in release and spread in the environment. However, overall losses and impact to commercial aquaculture can be kept low if vaccination procedures are implemented effectively.

Vibrio spp. can be diagnosed easily as it grows readily on or in standard culture media. Differentiation at the species level is more difficult but biochemical tests and PCR based assays are available. When fish succumb to Vibrio a range of external and internal clinical signs can be observed. Mortality in unvaccinated fish is usually high and infection results in a bacteraemia with fish showing signs of lethargy, dark colouration, reduced feeding response, and possible petechial haemorrhaging near the belly and base of the fins. Anaemia is common and multiple organs can be impacted.

As mentioned, vaccination is the preferred method of prevention for vibriosis; however, if outbreaks occur it is important to remove moribund and dead fish quickly and diagnose early in case antibiotic treatment is needed. As more species are reared in marine environments, there is concern that new problems involving vibriosis will develop and require additional strategies for control and prevention.

11.3.7 Yersinia ruckeri

Enteric redmouth (ERM) caused by the Gram‐negative bacterium, Yersinia ruckeri is a major cause of disease in aquaculture worldwide. ERM was first described in rainbow trout in the 1950s in the Hagerman Valley of Idaho, USA and referred to as Hagerman red mouth disease. This disease may also be referred to as yersiniosis in areas outside the USA and primarily impacts rainbow trout. Movements of fish and eggs are thought to have contributed to early spread of Y. ruckeri, and it was found in Canada shortly after initial isolation in Idaho. In the mid‐1980s it was reported in Europe and has since been found in Norway, Denmark, UK, France, Germany, Italy, South Africa, and Australia. One difficulty linked to ERM is that multiple varieties of Y. ruckeri strains or biotypes exist and may be linked to disease severity in salmonids. Outbreaks can cause significant impact and surviving fish can become asymptomatic carriers. However, similar to vibriosis, ERM is generally preventable by the use of commercial vaccines. Prior to vaccine development, it was believed that ERM caused up to 35% loss and an economic impact of approximately USD 2.5 million in Idaho’s Hagerman Valley.

ERM is readily confirmed through culture of Y. ruckeri in general media followed by biochemical tests and or other confirmatory serologic methods or PCR. This bacterium is motile and measures 0.5–0.8 × 1.0–3.0 μm. Although it impacts rainbow trout and other salmonids at colder temperatures (generally 15 °C or below) growth is optimal between 22–25 °C. As mentioned, different strains or biotypes exist. The Type I (Hagerman strain) is usually considered the most virulent. It has been found that the biotype of Y. ruckeri can be linked to vaccine efficacy and understanding this is important when developing vaccination programs. Separate biotypes have been found in Europe and North America, and recent atypical biotypes found in Australia were linked to high mortalities in Atlantic salmon (Bridle et al., 2012).

Acute infections with Y. ruckeri in young fish result in heavy losses as it causes a septicaemic infection. More chronic infections may appear in larger fish where clinical signs can include dark colouration, blindness, and lethargy. Ulceration and haemorrhaging in the mouth are classic signs and reflect the name ‘red mouth’. This is observed regularly in rainbow trout but infections in Atlantic salmon may not produce this classic sign. Often, ERM results in a septicaemic condition where internal clinical signs may include bloody ascites, enlarged spleens, as well as intestinal and muscular haemorrhaging.

Some antibiotics have been used to control mortality following ERM outbreaks. However, the most effective means of prevention and control for ERM is through the use of commercially available vaccines. Development of commercial immersion ERM vaccines was considered the single most important management tool for the trout industry in Idaho when introduced, and clearly limited the potential impact of ERM early on. Although vaccines are effective, it is important to implement good fish culture practices and minimise environmental stressors that would contribute to reduced disease resistance in any aquaculture situation.

11.3.8 Renibacterium salmoninarum

Renibacterium salmoninarum is a Gram‐positive bacterial pathogen that causes bacterial kidney disease (BKD), which was first described in Scotland in 1930. This disease is considered a problem in salmonids but has been reported in non‐salmonids such as ayu (Plecoglossus altivelis) and Pacific hake (Merluccius productus), and it was found that sablefish (Anoplopoma fimbri) developed clinical disease when experimentally challenged with R. salmoninarum. Most salmonid producing countries in Europe, Asia, as well as North and South America have reported BKD outbreaks in farmed and/or wild fish. At this time Ireland, Australia, and New Zealand are considered BKD free. Renibacterium salmoninarum is transmitted both horizontally and vertically. This poses serious problems in aquaculture programs where broodstock are highly valuable. To manage the problem of vertical transmission, resource enhancement hatcheries in the Pacific north‐west, USA have implemented an effective screening program for migrating adult Pacific salmon collected for hatchery production. Kidney samples from each female broodfish are taken at the time of spawning and infection levels are quantified using a standardised enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). If fish test positive with moderate or high levels of R. salmoninarum the fertilised eggs from that female are culled from the population. This has resulted in substantial reduction in overall incidence of BKD in these hatchery programs.

Renibacterium salmoninarum is considered a coryneform bacterium that is a non‐motile short rod measuring 0.3–1.0 × 1.0–1.5 μm. It is an intracellular bacterium and standard culture methods for identification are problematic as it grows slowly under most conditions, taking from 8–12 weeks to produce colonies at 15 °C. Improved culture methods can shorten this to as few 5–7 days. This may improve diagnosis of R. salmoninarum in the future; however, current confirmation of infections relies on serological or molecular methods.

Cases and reports of BKD are widespread and in general juvenile salmonids are severely impacted by BKD. However, adult fish can develop clinical disease in both freshwater and marine environments. Both wild and hatchery produced Pacific salmonids and Atlantic salmon can be affected by R. salmoninarum. Disease severity increases when smolts are transferred from freshwater to seawater most likely due to the physiological stresses of the smoltification process. Coho salmon smolts infected with R. salmoninarum experienced much higher mortality when held in seawater compared to siblings maintained in freshwater.

Clinical BKD may include a number of signs including darkening of the skin, lethargy, exophthalmia and abdominal distention. Spawning fish with heavy infections may show haemorrhaging at the base of their fins and internally can exhibit classic white‐grey granulomatous lesions in the kidney. The bacterium can be isolated from other organs as well, and in some cases the infection can move into the musculature where tissue destruction and necrosis may occur.

Prevention of BKD is best achieved through avoidance of exposure to R. salmoninarum. For broodstock that may be potential carriers, it is important to utilise the screening and egg culling methods described above. Movement of fish or eggs into facilities should require prior inspection of fish or eggs to determine disease status. If R. salmoninarum is endemic to a region, it is possible that outbreaks could occur. This may require antibiotic treatment of infected fish; however, few antibiotics have been successful. Use of erythromycin is common, but overall it has been relatively ineffective in young fish. A vaccine for BKD is commercially available and developed for Atlantic salmon. This is a live vaccine, but interestingly it consists of the bacteria Arthrobacter davidanieli, which is a closely‐related soil bacteria that provides cross‐protection when fish are injection‐vaccinated.

11.3.9 Streptococcus spp.

With the expansion of tilapia (Oreochromis spp.) aquaculture globally, one of the major disease problems has involved streptococcal septicaemic infections. Although most prevalent in freshwater fish, infections have also been reported in both wild and farmed marine fish. In freshwater, the following bacterial species appear to be the most problematic; Streptococcus agalactiae, S. iniae, S. ictaluri, S. difficile, and S. shiloi.

Streptococcal organisms are small Gram‐positive bacteria that may occur in chains consisting of 0.3–0.5 μm cocci. They can be isolated from various organs and cultured on different nutrient media. They are considered non‐motile and those associated with infections in fish have been divided into four primary groups based on specific characteristics.

Outbreaks have been reported in many fish species, but cumulative mortalities in tilapia have been reported as high as 50–60%. Clinical infection results in a variety of external signs including, but not limited to exophthalmia and petechial haemorrhaging near the operculum, anus, mouth, and fins. Internally, the intestinal tract, pyloric caeca, and liver may show petechial haemorrhaging. Once systemic, bacteria can move to various organs including the liver, heart, kidney, stomach, intestine, brain, eyes, and musculature. Outbreaks with S. agalactiae have been reported to cause mass mortality in tilapia. Streptococcal infections can also be a problem in catfish culture, and rainbow trout have been experimentally infected.

Prevention and control of streptococcal infections is difficult; however, it is important to maintain good water quality and minimise stress in an aquaculture setting. Removal of moribund or dead fish is important and should an outbreak occur, there have been reports of antibiotics such as enteroflaxin and erythromycin‐doxycycine being effective (Tung et al., 1985). In recent years, work has been carried out to develop vaccines to protect fish from major disease impacts. In tilapia, vaccines have been shown to be efficacious when injection delivered, and antibody mediated protection appears to be important. A commercial vaccine consisting of inactivated S. agalactiae (Biotype 2) is available for cultured fish but must be delivered via injection. Caution should be taken when handling fish suffering from streptococcal infections as some Streptococcus spp. are considered zoonotic and can cause infections in humans, which typically happens due to injuries to the skin while handling or preparing fish for cooking (see section 11.12).

11.4 Fungi

Fungi are considered eukaryotic organisms and are often referred to as water molds or oomycetes. They are microscopic, filamentous, absorptive organisms that function as decomposers in ecological systems. They reproduce both sexually and asexually and can produce toxins that may be harmful to animals. These water molds may be referred to as pseudo‐fungal organisms and cause diseases such as saprolegniasis and branchiomycosis, which are discussed in this section.

11.4.1 Saprolegniasis

Saprolegnia disease (saprolegniasis) can develop and impact cultured and wild fish or their eggs/embryos. In general, Saprolegnia is considered an opportunistic pathogen that feeds on necrotic tissue or organic debris. When conditions are optimum Saprolegnia can cause infection in just about any fish species at any life stage. However, infections are most prevalent in aquaculture facilities during egg incubation or early larval rearing or may become a problem in pre or post spawning salmonid broodstock.

Saprolegnia are classified as fungal‐like organisms and with filamentous hyphae, sporulation, and a classic ‘cotton tuft’ like appearance. However, some differences separate them from true fungi and place them more closely taxonomically to heterokonts, which include organisms such as diatoms and brown algae. Presumptive diagnosis may rely on visualization of cotton‐like tufts and identification of non‐septate filamentous hyphae. Confirmation to species level is difficult by microscopy, but genetic sequencing based on PCR identification is becoming more common. In most cases Saprolegnia are rarely diagnosed to the species level since treatment procedures are identical for all. Nevertheless, common species that are known to infect fish or fish eggs include S. parasitica, S. diclina, and S. ferax (see Cain and Polinski, 2014).

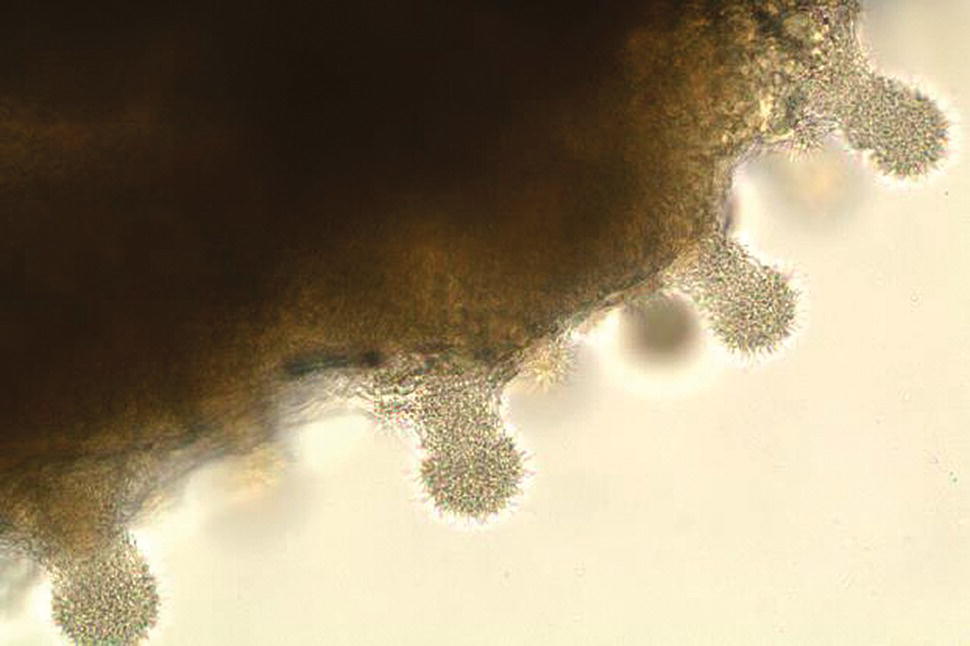

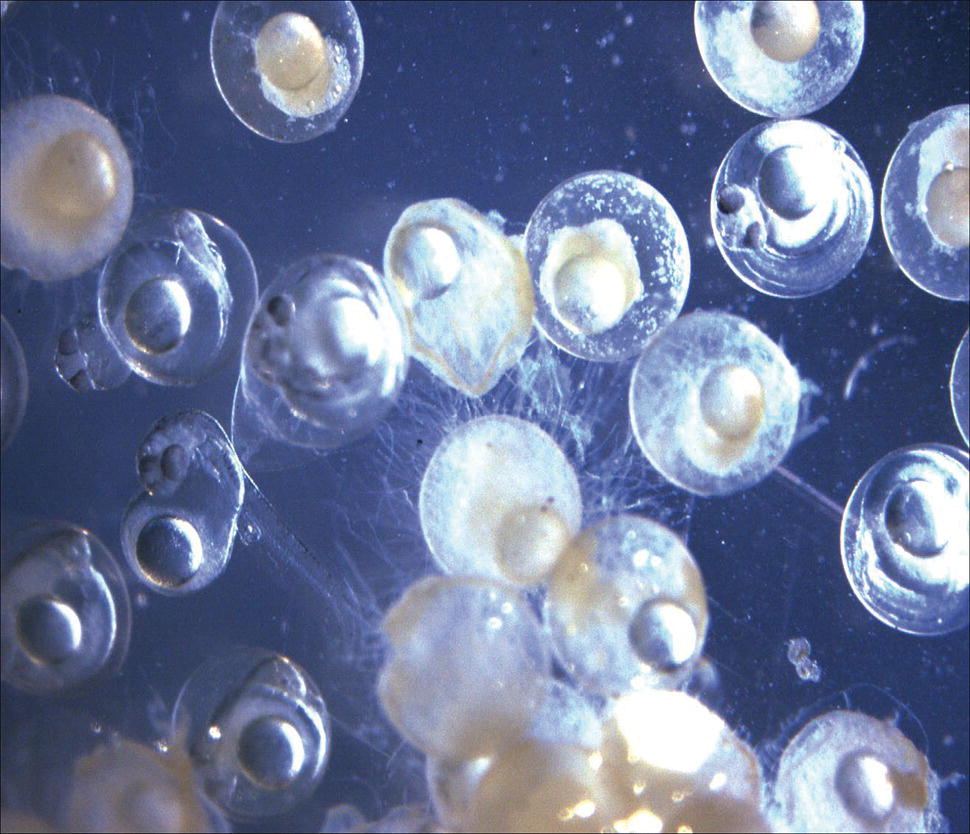

In general, Saprolegnia is opportunistic and can parasitise at temperatures ranging from 2–35 °C. In most aquaculture operations, S. parasitica is considered the most prevalent and concerning. Costs associated with this pathogen are estimated to be in the tens of millions of dollars in salmon and catfish culture facilities annually. Although S. parasitica is more common, S. diclina and S. ferax are considered more pathogenic than S. parasitica to Atlantic salmon eggs during incubation. New aquaculture species such as burbot (Lota lota), which require temperatures below 4 °C for egg incubation are highly susceptible to Saprolegnia (Figure 11.10). It was shown that without administration of chemical treatments, mortality of both eggs and larvae due to Saprolegnia was near 100%.

Figure 11.10 Characteristic hyphae shown attached to incubating burbot eggs. Eggs clearly infected with Saprolegnia appear cloudy and are dead, while visibly uninfected eggs appear healthy with developing embryos inside.

Source: Reproduced with permission from Dr M. Polinski.

Infection with Saprolegnia in fish will often start at the site of a previous injury or even a lesion resulting from other infections. Saprolegnia will manifest and appear as cotton‐like tufts on the external surface of the lesion of a fish or will rapidly spread once an infection is established on the surface of eggs. If fish are immunocompromised in any way as a result of predisposing stress or other factors, infection with Saprolegnia may be enhanced (Cain and Polinski, 2014).

Saprolegnia are considered ubiquitous in most freshwater environments and therefore fish or eggs will likely be exposed in an aquaculture facility. Infections can be limited in fish by minimizing stress and maintaining optimum culture conditions. Handling can cause physical injury, which predisposes fish to fungal type infection at these sites. For incubating eggs or newly hatched larvae, Saprolegnia may develop if nutrients are present; therefore, it is important to clean all organic material including dead eggs or egg shells as often as possible. Standard procedures in most facilities utilise routine treatments of eggs (and possibly larvae) with approved chemicals such as hydrogen peroxide, formalin, or in some cases sodium chloride. For fish, such as adult salmon, that may be heavily infected at sites where skin abrasions and damage occur (common if utilizing wild broodstock returning to spawning grounds), it is important to administer treatments as soon as possible. Malachite green was an early historic treatment and was quite effective; however, it is no longer allowed as it was found to have carcinogenic and toxicological effects. In the US, formalin and hydrogen peroxide are the most common chemicals used to treat saprolegniasis.

11.4.2 Branchiomycosis

Branchiomyces sanguinis and B. demigrans infections cause a condition known as ‘gill rot’. Branchiomycosis is known to impact cultured fish and has been linked to severe losses in tilapia in Israel and in farmed catfish. This condition can be linked to poor environmental conditions that affect gill health and provide an environment that favours colonisation of Branchiomyces on the gills. This condition occurs at temperatures between 25–32 °C and may manifest within 2–4 days following exposure if predisposing stressors are present.

To diagnose and distinguish between B. sanguinis and B. demigrans, gill preparations should be examined under light microscopy. B. sanguinis infects the lamellar capillaries and is characterised by a (0.2 μm) thin hyphal wall and spores of 5–9 μm in diameter, while B. demigrans is found in the parenchyma of the gills and is thicker with walls of 0.5–0.7 μm and spores measuring 12–17 μm. Gill rot may result in high mortalities and clinical signs of disease include those typical of most gill problems. These include lethargy and gulping of air at the surface of the water. Examination of fish may show striated gills with pale areas of necrosis due to infection.

Unlike Saprolegnia it does not appear that Branchiomyces are ubiquitous in the environment and movement of infected fish should be prevented. Prevention of disease is directly linked to good management practices that maintain high water quality and minimise other stressors in an aquaculture setting. Infected fish are considered carriers of these pathogens and should be separated from non‐infected fish. Treatment with formalin or copper sulphate may be effective at controlling mortality due to branchiomycosis, but to limit the spread of these pathogens all dead fish should be disposed of appropriately and ponds dried and disinfected.

11.5 Protozoans

Protozoans are among the most significant parasite problems in bivalve and finfish aquaculture industries where open water sources are utilised. They comprise a diverse group of unicellular eukaryotic organisms, many of which are motile. Protozoans range from 10 to 52 micrometers, but can grow as large as 1 mm, and can be observed using a microscope. The protozoan cell has one or more nuclei, a set of cellular organelles and special organelles serving vital functions such as locomotion, food intake or invasion of the host organism. Some parasitic protozoa have life stages alternating between proliferative stages and dormant cysts. As cysts, protozoa can survive harsh conditions, including exposure to extreme temperatures or harmful chemicals, or long periods without access to nutrients, water, or oxygen. At present there are no commercial vaccines available for any fish‐parasitic protozoa. This section provides an overview of the most common groups that occur in aquatic animals including flagellates, amoebae, haplosporidians, apicomplexans, microsporans and ciliates (Figure 11.11).

Figure 11.11 Schematic diagram of representative protozoa that may be present in invertebrate and finfish aquaculture. (a) flagellates (e.g., Icthyobodo); (b) amoebae (e.g. Paramoeba); (c) haplosporidians (e.g., Bonamia); (d) apicomplexans (e.g., Perkinsus); (e) microsporidia (e.g., Thelohania); and (f) ciliates (e.g., Cryptocaryon).

Source: Reproduced with permission from Dr Kate Hutson, graphics by Eden Cartwright, Bud Design.

11.5.1 Mastigophora (Flagellates)

The subphylum Mastigophora includes the dinoflagellates, blood parasitic trypanosomatids and ectoparasitic bodonids (Figure 11.11a). This group is characterised by elongate flagella (singular: flagellum) which undulate to propel the cell through liquid environments. Flagella are ‘whip‐like’ extensions of the cell membrane with an inner core of microtubules. Most parasitic flagellates have a simple, one‐host life cycle and reproduce by longitudinal binary fission.

The dinoflagellate Amyloodinium ocellatum is a dangerous agent of marine aquaculture fishes, causing fatal epidemics worldwide. Outbreaks can occur rapidly and result in 100% mortality within a few days. Amyloodinium has a direct but tri‐phasic life cycle. The parasites feed as stationary trophonts on the epithelial surfaces of the skin and gills. Trophonts attach to fish with an attachment disc that has filiform projections (rhizoids) that embed deep into the epithelial tissue of the host. After reaching maturity the trophont detaches from the fish skin and forms a reproductive cyst, the tomont, in the substrate. The tomont divides forming multiple free‐swimming individuals (dinospores) that can infect a new host. Under optimal conditions that parasite can complete its life cycle in less than one week. The severe disturbance of the parasite on the epithelia can lead to infected fish rubbing their body against objects or hard surfaces and osmoregulatory problems. Infections can result in hyperventilation, anorexia and mass mortality. The free‐swimming dinospore is suceptible to certain drugs, but trophonts and tomonts are relatively resistant, making eradication challenging. Infection can be diagnosed by observing parasites through light microscopy and molecular diagnostic tools have been developed.

Ichthyobodosis is an important parasitic disease that has caused severe loss among ornamental and farmed fish worldwide. Infections by members of the genus Ichthyobodo (Figure 11.11a) have been reported from more than 60 different host species in freshwater and seawater. The disease is caused by heavy infections on the skin and gills. In the past, infections have commonly been associated with a single variable species, Ichthyobodo necator. However, molecular studies have revealed that the genus Ichthyobodo consists of several different species. Two life stages are known, a kidney‐shaped free‐swimming stage and a sessile pyriform state which penetrates the epithelial cell lining. Infected fish may show discoloration of the skin and hyperventilate. Osmoregulation of fish hosts may be impaired due to destruction and fusion of gill lamellae and can cause considerably morbidity and possibly mortality. Both life stages are susceptible to formalin and oxidising agents.

Trypanosomes are parasites of invertebrates and fishes worldwide in freshwater and marine environments. They are normally found in the blood system, on the gills or in the digestive system. These parasites have a complex life cycle, with several development stages within the intestinal caecae of an intermediate leech host. Leeches may transfer blood trypanosomes (e.g., Cryptobia spp.) when they bite fish, although some species may be transmitted directly between hosts. Blood smears on stained slides show the presence of these parasites using light micropsy. Anaemia may result due to haemolysins released from the parasites; lipids and proteins that cause lysis of red blood cells by destroying their cell membrane. Young fish tend to be more vulnerable and mortality can result from an infection.

To avoid infection by parasitic flagellates there should be high filtration and treatment of receiving water. Leeches and other blood‐sucking parasites such as gnathiid isopods can serve as vectors of flagellates that infect the blood system and should be eradicated to reduce transmission. External flagellates may be treated with formalin, hydrogen peroxide or hyposalinity (for marine species) and some anaesthetics can cause flagellates to detach. High or low temperatures or salinity may inhibit multiplication of flagellates but may not be feasible for the host organism.

11.5.2 Sarcodina (Amoebae)

Most species of amoebae are free‐living although a small number are parasitic in animals. In aquaculture amoebae can be problematic for crustaceans, echinoderms and fish. Amoebae exhibit locomotion by the formation of pseudopodia (false feet) or by distinct protoplasmic flow. Movement is also used by many species to engulf and ingest food items by phagocytosis. Amoebae are extremely robust and survive under a wide range of challenging environments. They reproduce by binary fission or multiple fusion.

Paramobae perurans (the causative agent of amoebic gill disease) has become an issue for Atlantic salmon farming worldwide and affects a range of farmed marine fish species. Presently amoebic gill disease is a major issue for salmonid aquaculture in Australia, Ireland, Scotland, Norway and the USA with 10% to 82% mortality (see section 17.8). The severity of the disease is largely influenced by high salinity and high temperature. Clinical signs include respiratory distress and lethargy, which are associated with grossly visible gill lesions. The case definition of amoebic gill disease is based on histology, the presence of hyperplastic lesions and associated amoebae. The disease causes characteristic changes in the gill tissue, including severe hyperplasia of lamellar epithelium and an inflammatory response which leads to mortalities if left untreated.

The most effective treatment for P. perurans is a fresh water bath for two hours which alleviates pathological signs of infection. Gills are usually scored based on macroscopic examination to indicate the necessity for bath treatment, but there are limitations with this method because it is based on subjective interpretation and experience. Baths are stressful to fish and impact production, because fish need to be starved prior to bathing. There is evidence that a percentage of amoebae can survive and recover from a fresh water bath as they are able to form vacuoles to separate and then expel influxes of freshwater (Lima et al. 2015). Excluding caged salmon from upper cage depths where free‐living P. perurans tend to be more abundant could be an effective management strategy to reduce the speed at which initial infections occur. Use of cleaner fish as a biocontrol may be limited as many species are susceptible to amoebic gill disease.

11.5.3 Haplosporidia

The protist phylum Haplosporidia comprises over 40 described species with representatives infecting a range of marine mollusc hosts with some found in freshwater. They produce spores without the complex structures found in similar groups (such as polar filaments or tubules), but the spore stage has ornamentation consisting of tails or wrappings (Figure 11.11c). Haplosporid spores have a single nucleus and an opening at one end, covered with an internal diaphragm or a distinctive hinged lid. After emerging, it develops within the cells of its host, usually a marine mollusc or annelid. They develop within the digestive system and undergo internal budding to produce multicellular spores. The dynamics of haplosporidians in their hosts is seasonal and depends on environmental parameters.

Bonamiosis is a lethal infection of the haemocytes of flat oysters caused by Haplosporidia in the genus Bonamia (see section 10.5.1.1). This intrahaemocytic protozoan quickly becomes systemic with overwhelming numbers of parasites coinciding with the death of the oysters. Infection in oysters rarely results in clinical signs of disease and often the only indication of the infection is increased mortality. In some cases, the disease is accompanied by yellow discoloration and lesions on the gills and mantle, but in most cases infected oysters appear normal. Lesions can be detected by histology and may occur in the connective tissue of the gills, mantle, and digestive gland. Although the life cycle is unknown, it has been possible to transmit the disease experimentally in the laboratory by cohabitation or inoculation of purified parasites. Bonamia ostreae has been associated with considerable devastation of oyster populations. It was first observed in France in 1979 and caused substantial destruction of Ostrea edulis populations before spreading through much of Atlantic coastal Europe.

Similarly, outbreaks of Haplosporidium nelsoni along the mid‐Atlantic coast of the USA have devastated oyster populations and caused significant economic disruption of coastal communities. Oyster mortality associated with outbreaks can exceed 90%, producing significant financial losses for oyster industries. Haplosporidium nelsoni is believed to have been introduced to the USA from Asia. It infects the Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas) in Asia, Europe and the west coast of the USA and the eastern oyster (C. virginica) along the east coast of North America and Canada. Mortalities are usually highest in the summer months, and also increase in higher salinity waters. The disease reduces the feeding rates of infected oysters and reduction in stored carbohydrates inhibits normal gametogenesis in the spring, with a reduction in fecundity.

11.5.4 Apicomplexa (Sporozoans)

The phylum Apicomplexa is a large group of protozoan parasites with over 8000 species described as parasites of invertebrate and vertebrate hosts. Apicomplexans have a special cell organelle, the apical complex, which facilitates invasion of the host cell (Figure 11.11d). They undergo cyclic development involving three divisional processes: merogony, gamogony and sporogony. Cell division can occur by fission or endogeny. Fish apicomplexans are divided into two major groups; coccidia are primarily intestinal parasites, while haematozoa are blood parasites which have stages in fish with spore formation in leeches or gnathiid isopods. Species are usually differentiated based on the morphology of the spore, also termed the oocyst.

Several species of the genus Perkinsus are responsible for causing disease in molluscs including oysters, mussels, clams and abalone worldwide. Perkinsus olseni is the only species known to cause disease in the Asia–Pacific region and occurs in abalone, clams and pearl oysters. It was first described from the abalone, Haliotis rubra, in southern Australia. Perkinsus olseni is included on OIE’s list of notifiable diseases because infection can cause widespread mass mortality. Clusters of Perkinsus cells near the surface of the abalone appear as a white nodule or micro‐abscess in the foot and muscle. This develops to form a brown spherical pustule up to 8 mm or more in diameter. Transmission is direct from host to host and all life stages are infective, with parasite cells released from the host following host death and decomposition. Prevalence is highly variable depending on host and environmental conditions, but it is often 100%, as determined by histology or PCR. Infections can impede respiration and other physiological processes including growth and reproduction, and stress from high temperatures is believed to exacerbate the disease. Adaptive immunity is not known in oysters or other molluscs, so they cannot be immunised against Perkinsus species. Selective breeding of disease‐resistant strains may confer some protection against infection.

11.5.5 Microsporidia (Microsporans)

Microsporidia or microsporans are obligate intracellular parasites which lack mitochondria and form small unicellular spores. Microsporans proliferate in host tissues by merogony (asexual division) followed by sporoblastogenesis and sporogony (spore formation). Mature spores contain a unique coiled polar tube which everts forcibly to inject the infective sporoplasm into host cells (Figure 11.11e). Infections may be disseminated throughout the tissues or they may cause focal lesions, inflammation and granulomas.

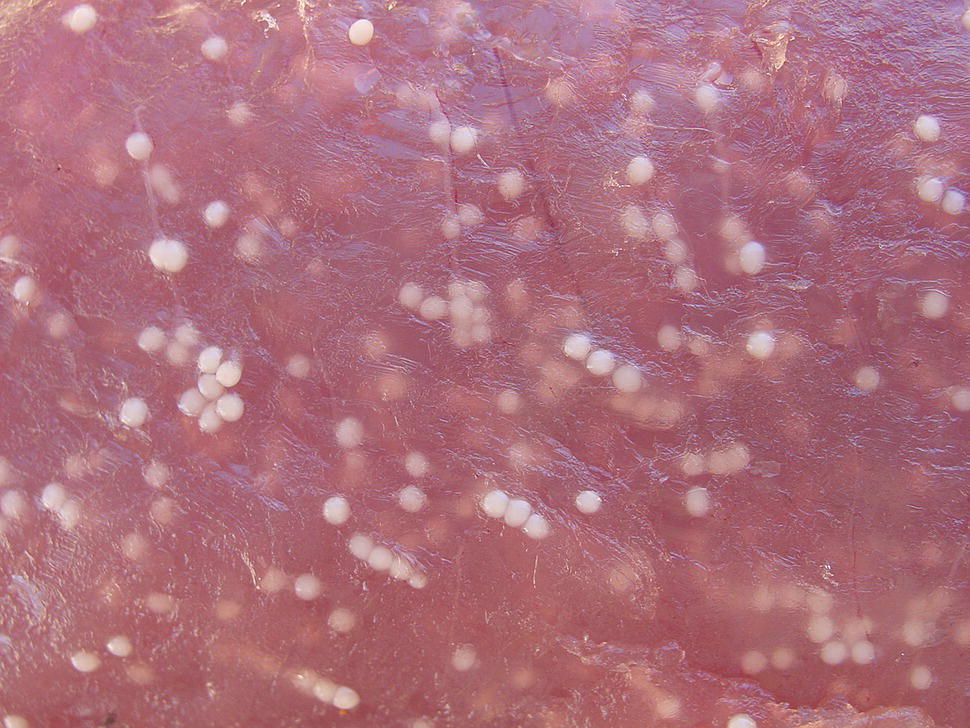

Microsporan species in the genus Thelohania (family Thelohaniidae) cause ‘cotton‐tail’ disease in aquatic crustaceans. Infections have been detected in most freshwater crayfish species, including wild and cultured marron (Cherax tenuimanus), yabbies (Cherax destructor) and redclaw (Cherax quadricarinatus). Heavily infected muscles become white in appearance and are unmarketable. Mildly infected crustaceans may be stunted in growth, while heavy infections may be fatal. Transmission is assumed to be direct, via water‐borne transport of infective spores and/or ingestion. In infected individuals, mature spores may penetrate adjacent cells, injecting infective sporoplasm which subsequently divides and ultimately forms new spores. Heavy infections can be detected macroscopically by visual examination of crayfish tails which are opaque in appearance, rather than translucent and clear. Alternatively, infections can be diagnosed by microscopic detection of cysts and spores in squash preparations or histology of the muscle. The most successful prevention of infection is to drain culture ponds, lime them and dry them before restocking. There are no drugs currently available to treat infestations.

11.5.6 Phylum Ciliophora

Ciliated protozoa are among the most common external parasites of fish but can also infect invertebrates. Most ciliates have a simple life cycle and divide by binary fission. Ciliates can be motile, attached, or found within the epithelium. Ciliates living in or on fishes range from harmless ecto‐commensals to dangerous parasites in fish aquaculture. With few exceptions, ciliates possess cilia at some stage of their life cycle. Asexual reproduction occurs by transverse binary fission. About 150 species occur in fish, most as ectoparasites causing fouling, irritation and local lesions and sometimes penetrating wounds. Some are endoparasites and can damage of the tissues or organs. Ciliates can irritate the surface cells, penetrate into deep tissue layers and ingest the cell debris produced.

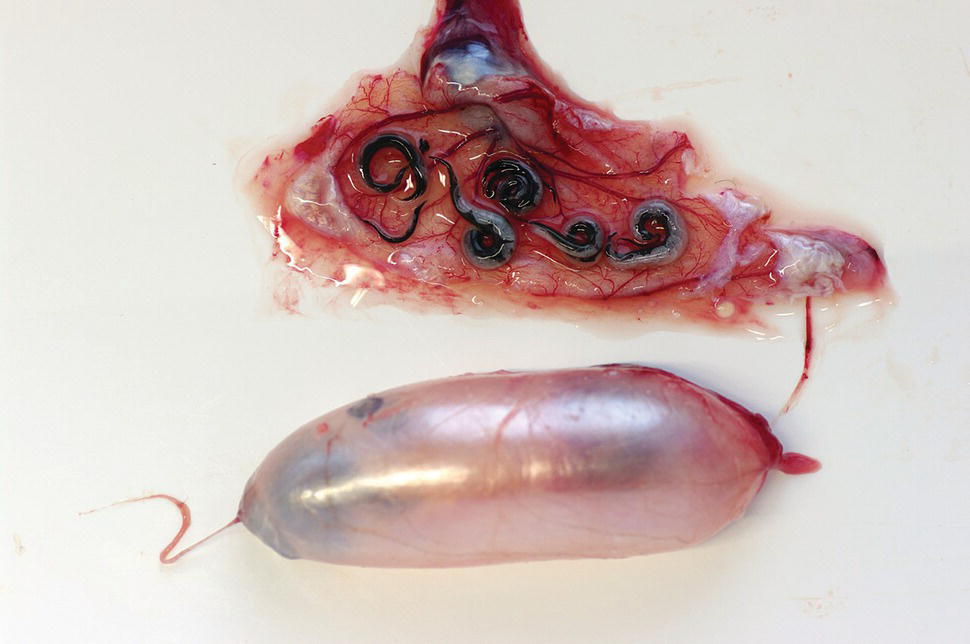

Some of the most important ciliates in captive freshwater fishes include Ichthyophthirius multifiliis, Chilodonella spp., the trichonids (including Trichodina, Trichodinella, Tripartiella, and Vauchomia spp.) and Tetrahymena species. In fish confined to ponds, tanks or aquaria, ciliates that live freely in the water column, such as Trichodina spp. and Chilodonella spp., can form dense populations on fish resulting in morbidity and mortality. Chilodonella spp. have a voracious appetite for living cells and use a specialised mouth organ, the cytostome, to graze on bacteria, diatoms, filamentous green algae and cyanobacteria present on biofilm substrates of fish gills and skin.