Just like any project we do in life, whether it’s to plan a trip, build a tree house, or start a business, careful planning will be a critical step and most likely will make the difference between success and failure. Athletic performance, and in this case, triathlon training, is no different. Developing a training plan is a crucial step in maximizing performance for every athlete. Doing it well will help you identify clear goals, understand your current level of readiness, and establish an accurate training regimen. The annual plan should be your training road map. It should be the instrument that guides training and facilitates improvement in technical, physiological, and psychological abilities. Planning is by far the most important tool you have regardless of your level of knowledge and experience. The planning process requires you to take a realistic look at your current position on a frequent basis throughout the season. It requires you to acquire new information and then make decisions on how you are going to train.

The objective of every training program is to ensure peak performance on a specific date. This is a challenging task that is often hard to achieve. For example, insufficient rest in the training plan will most likely cause the athlete to reach peak performance before the desired race date. On the other hand, not enough training will most likely result in peak performance after the desired race date. Knowledge, a methodical approach, and experience are the key factors in building that plan. Poor planning will lead to an inaccurate peak performance and a decrease in motivation, and it can dramatically increase the chances for injury and overtraining.

Periodization is the gold standard of developing an annual training plan. Knowing your goals and understanding your current level of fitness make up the first step of a successful plan. Although the concept of periodization and the development of a yearly plan vary a bit from one sport to another and even between coaches within a sport, the basics are still the same. I will try to convey them to you in this chapter.

The term periodization comes from period and means dividing a certain amount of time, in this case the training year, into smaller, easier-to-manage phases. The periodization concept is not new and was used in many forms as far back as the ancient Olympic Games. Many coaches, in a variety of sports, use the periodization concept, although the names, number, and length of phases in the plans might be slightly different. The most common periodization refers to three segments of time that repeat themselves and differ by size: macrocycle, mesocycle, and microcycle.

The macrocycle is a long stretch of training that focuses on accomplishing a major and important overall goal or a race. For example, if the Chicago Triathlon is your most important race of the season, the time from the first day of training at the beginning of the season until that race will be what you consider your macrocycle. A macrocycle is then made up of a number of different small- and medium-size phases and covers a period of a few weeks to 11 months.

For most athletes, and especially beginners, a macrocycle covers the entire racing season, focusing on one big race for the year and the development of basic physical and technical skills. More advanced and elite athletes will have two or three macrocycles per racing season; elite athletes race multiple important races per season because they may need to accumulate points or qualify for the championship race. The number of macrocycles mostly depends on the number of times these athletes need to reach peak performance within a given racing season. Elite athletes preparing for Olympic competition often use macrocycles to represent a 4-year cycle, planning different or progressive goals for each of the 4 years.

The mesocycle can be a confusing concept, as its definition might be different from one coach to another. In general, the mesocycle is a shorter block of training within the macrocycle that focuses on achieving a particular goal. A mesocycle usually covers 3 to 16 weeks and will repeat a few times within a macrocycle, each time with a different training objective or goal. There are three mesocycles, or phases, that coaches often use within the annual training plan: preparatory, competitive, and transition. These phases can be (and most of the time are) divided into smaller, more specific subphases because of the different training objectives for each.

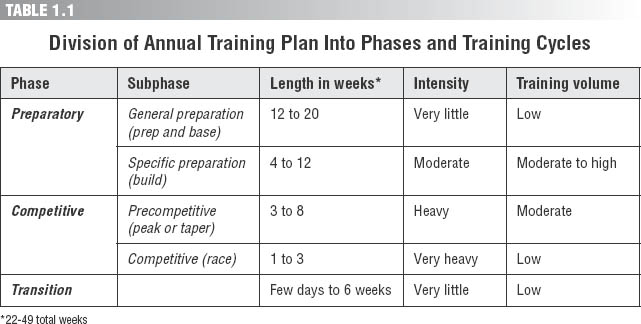

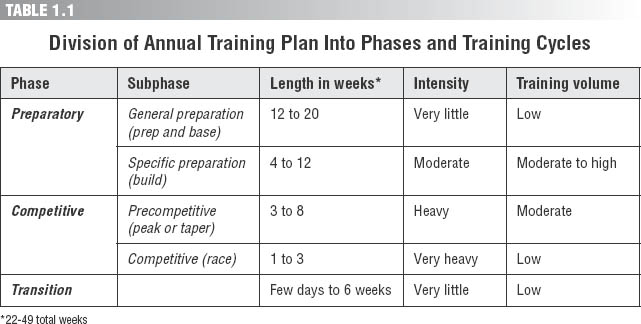

The preparatory phase is the period that establishes the physical, technical, and psychological base from which the next phase, the competitive phase, is developed. The preparatory phase is divided into general and specific preparation subphases. The general preparatory subphase focuses on developing high-level conditioning to tolerate the demands of both training and competition. The specific preparatory subphase also has the objective of elevating athletic working capacity specific to the demands of your race. Some coaches call these subphases “prep” and “build.” The next phase, the competitive phase, is divided into precompetitive and competitive subphases. The objective of this phase is to perfect all training factors to ensure successful racing. The precompetitive subphase uses racing to test your ability. It’s an objective feedback for your training and level of preparation. The competitive subphase is dedicated to maximizing your fitness for maximum performance. Finally, the third phase, called the transition phase, is the rest and rejuvenation phase in between training cycles or seasons.

The size of each mesocycle, or phase, is different and is mostly related to the training objective for that particular phase of training and its position within the race schedule. In the preparatory phase, the objective is to develop technique, endurance, and an overall conditioning foundation. These elements take a long time to develop, and therefore the preparatory phase will be the longest phase of your annual training plan. The competitive phase is shorter as the focus is on racing, which is very stressful, and therefore the amount of time you can be in that phase without detrimental effect on your body is limited. You will learn more about how to build the training phases in the section on dividing your season into training periods later in this chapter.

Keep in mind that the level of the athlete will also influence the length of each phase. For example, a beginner athlete most likely will have a very long preparatory phase, up to 22 weeks, if needed, to develop a strong foundation that will enable him to endure the load of progressive, more advanced training. On the other hand, an advanced athlete who has been training for a few years has already developed a strong foundation and may need only 12 to 16 weeks to get there, and therefore she can move to the competitive phase of training more quickly.

Table 1.1 provides general guidelines on how to divide the training season (macrocycle) into mesocycles and what the length, intensity, and volume of each phase would be. Table 1.2 provides general guidelines of what the focus of training in each mesocycle should be. Although the focus in each of these phases is mostly the same for every athlete, the length, intensity, and recovery time of each period will change based on the athlete’s goals and athletic experience and the time the athlete needs to adapt to the training stress.

A microcycle is the basic training phase that repeats itself within the annual plan. The microcycle is the smallest training period within the annual training plan, and it is structured according to the objectives, volume, and intensity of each mesocycle. The microcycle is probably the most important and functional unit of training, as its structure and content determine the quality of the training process. A microcycle can last for 3 to 10 days, but in most cases, it refers to the weekly training schedule. The progression of the microcycles within a mesocycle has to take into consideration the important balance between work and rest. Too much work without appropriate rest will lead to overtraining and injuries. On the other hand, too little work with too much rest will lead to underperformance. The common ratios of work to rest in a microcycle are 3:1 or 2:1; however, in some extreme cases of heavy-load weeks (the combined stress produced by volume and intensity on the body), a 1:1 work-to-rest ratio is used. Work-to-rest cycles are called training blocks.

You should first plan each microcycle, rather than plan individual workouts, and start by taking into consideration the physiological adaptation you are looking for during a particular training phase. For example, in the preparatory phase, your microcycles will be focused on developing endurance; therefore the key workouts of those weeks should be long and of endurance-promoting intensity. In the competitive phase, your objective is to develop speed; therefore your workouts will be shorter in nature and at a much higher intensity. Thus, make sure the order of the training sessions within the week promotes the desired training effect for the week and is relevant to the training objective. In the preparatory phase, you should plan short, high-intensity workouts before long, steady-state workouts, with a recovery day between these days. However, during the precompetitive phase, you may change the weekly schedule a bit; instead of having a recovery day between two hard days, plan the week with a high-intensity day followed by a long-endurance day, and then schedule a recovery day. Doing so increases the physiological and psychological stress on the body and develops a higher level of fitness that is appropriate for this period in the annual plan. You’ll learn more about how to plan your weekly schedule later in this chapter.

The structure of the microcycle should also be based on training principles (i.e., developing general fitness before specific fitness; load progression that is specific to the level of the athlete; and a recovery period to reduce fatigue, energize the body, and provide time for fitness adaptation) while considering your ability, your past progress in training, and training and facility resources. Never develop more than three or four detailed microcycles at a time, as progression is not always as linear as you might predict. In addition, assess progress frequently, since progression and the training effect are highly individual and greatly differ from athlete to athlete.

Furthermore, training sessions scheduled within the microcycle should change from phase to phase based on the demand you want and to ensure progress. The physiological and psychological demands on the body should change every 4 to 6 weeks to ensure continued fitness development. This could be done simply by changing your weekly schedule around: Move the swim workouts one day forward and the run workouts one day back, switch your long bike workout day with your long run day, lift weights early in the day rather than late in the day, or just change the position of your rest day. These minor changes can have a great effect on the training stimulus. In addition, as we mentioned earlier, think of the delicate balance you need between the work done and the rest that is necessary to achieve these adaptations within a training week.

Now that you have a conceptual understanding of the building blocks of the annual training plan, you can start planning your racing season using periodization concepts and build your individual annual training plan. Applying periodization concepts to the process of building an annual training plan simply means developing a plan with training blocks where each block prepares the athlete for the next more advanced and more specific training period. Be patient, and be careful not to rush through the phases. Insufficient training in the preparation phase will result in the inability to maximize performance and will produce a higher risk of injury.

The best time to engage in building the yearly plan is a few weeks into the transition phase, just before the beginning of the new training season. It is essential to take a few weeks off after the last major competition to make sure you are mentally and emotionally recovered and can be objective in your planning process. Although it is tempting to find immediate solutions to last year’s shortcomings, patience will produce a better plan.

There are two major steps in putting together the annual plan. The first step is to analyze past performance and set goals and training objectives for the forthcoming season. This is a very important part that can easily be overlooked. At the end of this step, you should have a clear understanding of your true strengths and weaknesses, be clear about your racing goals for the season, and finally, know what actions you need to take to achieve these goals.

After you do this, the second step is laying down your goals and objectives and defining your training blocks. At the end of this step you will have a clear picture of your race calendar, know what your training blocks are and how long they are, know when your benchmark tests are going to be (you’ll learn more about these later in this chapter), and lastly, know the structure of your weekly training schedule.

To properly and accurately plan for peak performance for the upcoming year, it is essential to look at and understand your performance from the previous year or two. Past performance analysis should include past races, benchmark tests, and how they relate to the training plan. What worked? What did not? How consistent were you with the plan, and what effect did the training phases have on your performance? Doing this step well will help you identify your triathlon strengths and weaknesses and then adjust your new training program accordingly. If, for example, your bike segment on race day is consistently slower than that of your competition, you may want to add some bike-specific training blocks in the preparatory phase of the upcoming season. However, if you dedicated a significant amount of time to bike-focused training last season and still did not progress very much, you may have to look into changing your workout protocols and progression or changing your bike position or even your bike.

Pay particular attention to last year’s benchmark testing. Did you progress from test to test? Did the benchmark test consistently predict your race result or have no relevance to how well you did in your key races? If, for example, you were able to show progress from test to test but didn’t improve your performance on race day, you may be using the wrong test or you might need to add race-specific workouts in order to convert your workout fitness to race fitness. In addition, you may find that you need to change your testing protocols altogether because they may not be relevant to the fitness you are building. This process is critical and will play a major factor in this season’s training objectives.

Goals and training objectives are related but represent two different things. A goal is your destination (e.g., your key race, when you are going to do this race, and what the desired finish time or position in this race will be). Objectives are the milestones you need to reach in order to achieve your goal. Objectives are smaller goals that are derived from your major goal, and achieving them will increase your chances of achieving your major goal.

Setting goals can be tricky, and it should be done with proper balance between your emotions and reality. Your goal should be in line with your current athletic position and the time and resources you have for training on the one hand, but it has to stretch you on the other. A goal that is realistic but too easy to accomplish will not motivate you to go out and train. An unrealistic goal that is so far from your current athletic ability can be discouraging and can cause a great amount of stress. For the same reason, your goal should be believable. You need to know you can accomplish the goal in order to bring up the necessary energy to work toward it. If you can’t make yourself believe in your goal, you will not make the effort to train for it. Setting bad goals can be the cause of anxiety and stress; setting good goals will provide you with a sense of satisfaction, confidence, and calm—great assets when you are about to engage in endurance training and especially demanding and time-consuming triathlon training. It takes a great amount of courage and inner control to pick the right goals. Here are two principles that can guide you toward setting good goals:

1. Make your goal specific and measurable. For example, your goal may be to finish the Chicago Triathlon with a time of 2:05:00 or better. This goal gives you all the details you need. You now know what you want to do and when.

2. Make your goal stretchable and believable. For example, a time of 2:05:00 for the Chicago Triathlon should be a finishing time that you have never achieved before. However, you know that if you work hard and improve certain factors in your readiness, you can achieve it.

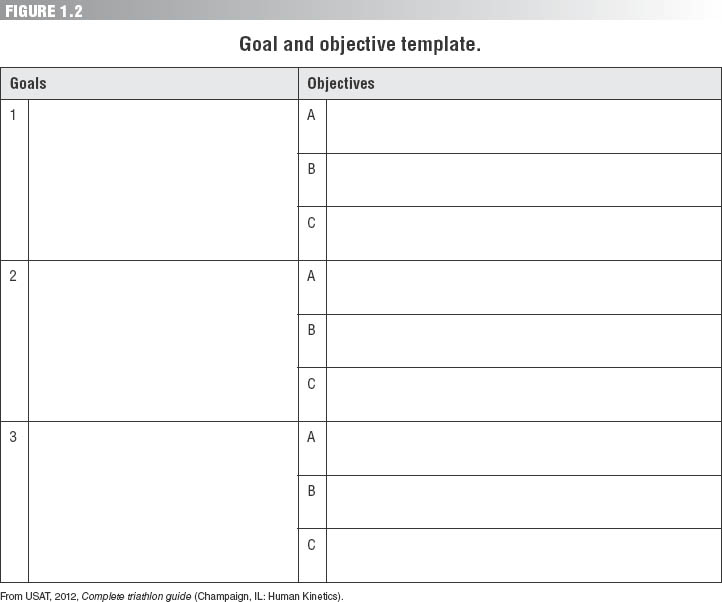

Once you have set your goals, you then need to set up objectives for your training plan. As mentioned already, objectives are the milestones or smaller goals you need to hit in order to make your major goal possible. Using the Chicago Triathlon time of 2:05:00 as an example, these subgoals should be derived from analyzing your past performance and determining your needs based on your strengths and weaknesses. Finally, your objectives will guide the training you need in order to improve your weaknesses and build on your strengths. Just like goals, training objectives need to be specific, measurable, stretchable, and believable and should be written in the same manner. Figure 1.1 gives you an example of what your goals and objectives may look like.

Figure 1.2 is a blank template you can use to define your own goals and objectives. As you can see, you first write down your top three goals, and within each of these three goals, you list three related objectives to help you meet that overall goal.

The race calendar is what drives the annual training plan. The races you select to do should first and foremost support your needs, level of development, conditioning, and psychological readiness. Before we begin, note that a blank training plan template has been included at the end of this chapter; see figure 1.3 on page 15).

Your key races (let’s call these your A races) are the major factor and the most influential element in your periodization. Place your key races on the annual training plan template first. Your secondary and training races (let’s call these your B and C races, respectively) will have lesser effect on your periodization, although they play an important role in your race preparation and fitness development for the upcoming key races. These races will be spread out mostly in the competitive phase at strategic times on the training plan template, including the end of a training block (three to eight microcycles) and 1 or 2 weeks before major competition.

Races should not be scheduled early in the preparation phase because the focus of training at this time is to develop basic fitness and skills. In addition, races impose extreme load on the body and may cause injuries if done too early in the preparatory phase. Secondary races should be scheduled in the annual plan to mirror the progression in training load toward the goal race. For example, if running is a major limitation and you want to use a half-marathon race as a B race, you should schedule the race far into the preparatory phase of the training plan, allowing sufficient time for proper training. The number of B and C races you schedule should be determined by your fitness level and your ability to recover and return to training after each race. Too many races on your schedule will interrupt your training and lead to premature peak performance. Too few races will lead to less-than-optimal performance at your major and most important race. In addition, proper taper and recovery must be built into the training plan, especially after B and C races that lead to your A race. More information about recovery is found in chapter 8, and tapering is covered in chapter 10. It is recommended that beginner and less experienced athletes reach peak performance once in their first and even second seasons and dedicate most of their training time to building basic endurance, strength, and skills. More advanced and experienced athletes may reach peak performance more often.

Once the race calendar is determined, try not to change it because the entire training plan is based on that schedule. In the event you need to change your race calendar, you may have to reset your training phases. If you are skipping or adding a B or C race, then a small adjustment in your plan may be sufficient. However, if it is an A race, you may have to reevaluate the entire plan, but stay true to your goals and training objectives.

Setting up your training period and the progression slope from period to period is the most important task in building your annual plan. Figure 1.3 on page 15 should help you set up your training phases and the number of weeks you should schedule for each phase. Training periods should be determined based on your race calendar and the number of times you want to reach peak performance in the upcoming season.

Again using figure 1.3, your annual training plan template, divide the season into phases by first making it useful for the current calendar year. In the date of the week column, place the date for each Monday for the entire year, starting with the first Monday of your training plan. Next, add the month’s name in the month column to the left of the first Monday of that month. Now you are ready to use the template for the current year. Place your races on the calendar, with the option of using different colors to differentiate between the importance of each of the races (e.g., A, B, or C race). Moving back from your key race (or in the case of more than one peak performance, from your first peak performance), start filling in the weekly focus column. For the competitive phase, start by setting up 2 or 3 weeks for the race period, then 3 to 8 weeks for the precompetitive phase.

For the preparatory phase, I suggest starting at the beginning of the training season with 3 to 5 weeks of acclimation, building your load from your transition-phase fitness level. Next, start marking training blocks of 3- or 4-week cycles until you meet the precompetitive phase on your plan. Early in the season, you may be able to endure a 4-week training cycle because the load of each week is somewhat low. Later in the season, as the demand of each training week increases, you may have to use a 3-week training cycle. You may also need to adjust the number of weeks in the last training block because the weeks of the training year might not divide exactly into your cycles. Once you are finished planning toward your first A race, you should do the same from the second A race. Continue dividing the season all the way down to the level of the microcycle.

Your next step is to assess your starting abilities. This can be done by asking yourself three simple questions:

1. What is the distance I can currently swim?

2. How long can I comfortably bike in time?

3. How long can I comfortably run in time?

These starting abilities will give you an idea of the required length of each workout in the first few weeks. My suggestion is to start at a lower volume than you are currently capable of; the combined effect of having a new and complete training routine may make the load much higher, and therefore a stand-alone 60-minute run might feel much harder within a full training program.

Next you should set up your weekly schedule. Start by choosing your day off, and then schedule your swimming days, biking days, running days, and weightlifting days. In most cases you want a day of easy recovery between high-intensity days. However, as mentioned earlier, that might change as you progress into more advanced stages in the plan.

Last, mark your mesocycles to the left of the month column, based on descriptions you put in the weekly cycle for each week and training block. As you can see, the planning of your season and the focus of each training block start from the end and go backward and are determined by the A race, your training objectives, and your level of fitness and experience.

As mentioned earlier, the progression slope normally includes 3- or 4-week cycles, but depending on the training phase, a 2-week cycle is used as well. Starting at the beginning of the preparatory phase, the first week in a 3-week cycle will have a training volume of about 30 to 40 percent of your maximum load. In the second week, the training volume will increase by 10 to 20 percent, and in the third week, the volume will drop by about 6 to 7 percent. Continue to progressively increase the training this way through the preparatory phase, maximizing your training volume toward the end of the general preparatory phase and the beginning of the specific preparatory phase, and stay that way for a period of one to three cycles. At that point, volume will start to decrease by about 5 to 10 percent per cycle and will stay at about 75 to 80 percent throughout the competitive phase. During taper, volume will decrease to about 50 percent of the maximum load.

On the other hand, intensity trails volume throughout the annual plan, starting at about 25 percent of maximum load, and stays around that level for 3 or 4 weeks. After that, intensity increases by about 15 percent every two or three training cycles, in the same way training volume increases and reaches its highest levels at the end of the specific preparatory phase. At that point, intensity levels will be just under volume levels and in some cases may match volume levels. During the precompetitive and competitive phases, intensity will stay around the same level, with slight variation to allow recovery and high-intensity race-simulation cycles. Toward the end of the competitive phase, training intensity should drop down to around 60 percent.

The ultimate goal of every athlete is to reach peak performance in key races throughout the season. You will achieve this goal through careful planning and proper progression of the training cycles in your annual plan. In the early part of the season, during the preparatory and competitive phase, you build your technical, physiological, and mental foundation. The last part of the competitive phase is where you start the process of peaking. Peaking, or taper, is achieved by manipulating volume, frequency, and intensity during the last one to four microcycles to reduce overall training load and maximize adaptation. Proper taper can be achieved by systematically reducing physiological and psychological fatigue while maintaining a high level of sport-specific fitness. Taper should last 1 to 4 weeks depending on the athlete, the pretaper load, and the race distance. In most cases an Ironman taper will last 3 or 4 weeks, and taper for an Olympic-distance triathlon leading to major competition will last 1 or 2 weeks. During taper you should maintain training intensity to prevent detraining, decrease training volume by 40 to 60 percent of the pretaper volumes, and keep the frequency of your training sessions at around 80 percent of pretaper frequency. Proper taper should lead to about a 3 percent improvement in performance.

Testing is a critical and integral part of the annual plan and should be performed throughout the season systematically and consistently. The main objectives of the tests are to determine your strengths and weaknesses; monitor your progress; and produce data that will allow you to calculate training zones, pace, and load. Test results should steer the training program and keep you on course toward reaching your goals. Baseline testing should be performed in each sport 3 to 5 weeks from the beginning of the program. Follow-up testing should be scheduled every 3 to 10 weeks after that.

For testing to produce meaningful results, make sure you test what you train or for data you may need for future training to calculate heart rate training zone or pace and power zones. Don’t train aerobically and look for progress at anaerobic endurance levels. In addition, make sure your training objectives are lined up with your goal. There are many lab and field tests that let you compare your performance against standards to see where you stand. However, don’t hesitate to use one of your favorite workouts as your test; a certain bike loop or a swim workout that always feels good can be a great measure of progress.

The timing of the tests is critical for producing accurate results. Most of your testing should be done in the preparatory phase to make sure your training produces the adaptation you are looking for. During the competitive phase, it is much harder to find the time for testing and to produce accurate results. The best time to test is at the end of or right after the recovery week of a certain training block.

As you learned earlier, the microcycle, or in other words, the weekly training schedule, is by far the most important period of the training program. Its design and content are the cornerstone of the annual training plan. You should consider the weekly schedule as a 7-day training program (could be as little as 3 and up to 10, but 7 days is most common) for achieving a predecided training adaptation. Based on the goals and objectives you set for the season, your weekly schedule should change from one training phase to another in order to promote different training loads. Another important factor in scheduling your workouts is the balance between work and rate of recovery. Too much load with too little rest will lead to injury and overtraining. On the other hand, too little load and too much rest will slow your progress dramatically and will prevent you from reaching peak performance.

There are many approaches to developing an annual training plan. Find or build the one that works best for you. Not having an annual training plan would be like walking in the dark and not understanding why you can’t see anything. Without a training plan, you will have no direction and will produce poor, or at best unpredictable, results. You should take the time at the beginning of the year to gather the proper information, establish goals, set objectives, and build a detailed annual training plan.

An annual training plan template will help you record and organize the information you gathered as well as plan the training phases down to the level of the training session. Figure 1.3 shows the template I have developed that works best for my needs. The template contains the yearly calendar by weeks and allows you to plan the year down to your weekly schedule and your individual workouts. It also allows you to change the plan from phase to phase and add any necessary information you might need in order to build a complete yearly plan.