Fig. 12.1. Recovery from unilateral left neglect (based on data in Hier et al. 1983b).

The Relationship between Lateralised and Non-lateralised Attentional Deficits in Unilateral Neglect

Medical Research Council Applied Psychology Unit, Cambridge, UK

Introduction

Posner and Peterson propose the existence of three broad classes of attentional mechanism—selection, orientation and vigilance/arousal. Posner has suggested that one aspect of orientation (i.e. disengagement) is a central aspect of unilateral neglect.

In the absence of evidence for differing hemispheric specialisation for orientation, it is difficult to explain the preponderance of left over right unilateral neglect once the acute phase is past. The present chapter hypothesises that severe, chronic unilateral neglect may require deficits in at least two attentional systems—disengagement/orientation and arousal/vigilance. Hence the preponderence of left over right neglect is explained by right hemisphere lesions affecting the vigilance system as well as the orientation system, while left hemisphere lesions only affect the latter. A number of studies are reviewed in the light of this hypothesis and, finally, some mechanisms of recovery from unilateral neglect are discussed, with indirect evidence of compensatory strategies in recovered neglect patients.

Precisely how the lateralised bias of attention and/or representation occurs in unilateral neglect has been the concern of most of the contributors to this volume. The purpose of this chapter is to examine to what extent unilateral neglect tends to be associated with non-lateralised attentional deficits, and to what extent any such deficits might contribute to the nature and natural history of unilateral neglect.

A number of different strands of evidence will be considered in turn: (1) the paradox of neglect (remission rates, laterality and chronicity); (2) evidence for deficits within ipsilesional hemispace; (3) evidence for increased neglect with increased attentional demands on non-visual/spatial aspects of tasks; (4) evidence for greater difficulties in feature vs conjunction search among neglect patients; (5) evidence for influence of arousal on neglect. A hypothesis is proposed which suggests that a full account of chronic neglect requires one to postulate the co-existence of at least two types of attentional deficit—one lateralised and one non-lateralised. This hypothesis is critically examined in the context of the five strands of evidence described above, and in the context of Posner and Peterson’s (1990) model of attention.

The Paradox of Neglect: Remission Rates, Laterality and Chronicity

The neglect paradox can be summarised thus: Recovery in the early stages is rapid and common for left brain-damaged patients, but right brain-damaged patients much less commonly recover completely, though the majority do so. Hier, Mondlock and Caplan (1983b) showed that unilateral spatial neglect (measured by Rey Figure left-side omissions) remitted very rapidly (all patients tested within 7 days of stroke), with the 35/41 patients who showed neglect at first testing taking a median of 8 weeks to recover on this measure. By 12 weeks post-stroke, there was an approximately 75% chance of full recovery. The equivalent figures for “neglect” (defined by “failure to attend to auditory or visual stimuli on one side of space”, otherwise unspecified) were 19/41 at intake, with a median 9 weeks to recovery, and an approximately 90% chance of recovery by 12 weeks. Figure 12.1 shows the results. In this study, the “best” remission candidates were: left neglect, prosopagnosia, anosognosia and unilateral spatial neglect on drawing (Rey Figure). Recovery was slower for hemianopia, hemiparesis, motor impersistence and extinction.

Fig. 12.1. Recovery from unilateral left neglect (based on data in Hier et al. 1983b).

Stone et al. (1991) followed up 44 consecutive patients who suffered an acute hemispheric stroke (18 right hemisphere, 26 left hemisphere) at 3 days and then 3 months post-stroke. Figure 12.2 shows the remission rates for the two groups on one of the tests of neglect, a line cancellation test. Altogether, 55% of right hemisphere subjects showed neglect at 3 days, as did 42% of the left brain-damaged subjects. By 3 months, the corresponding figures were 33% and zero, respectively. Hence it would appear from this last study that the incidence of right neglect is only slightly less than that of left neglect in the acute stages, but that recovery from right neglect is both more rapid and more complete. This differential recovery rate will be discussed later in terms of evidence for hemispheric specialisation for certain attentional functions.

Fig. 12.2. Recovery from unilateral neglect (based on data in Stone et al. 1991).

This relatively rapid remission of unilateral neglect in the first 3 months post-stroke, particularly for right neglectors, stands in contrast to the findings about remission of neglect in subjects recruited over a longer period post-stroke. Visual neglect has been detected in patients 12 years after their CVA, and the same retrospective study found no correlation between time since onset and extent of neglect among a group of 71 patients (Zarit & Kahn, 1974). Zoccolotti et al. (1989) found only a very small correlation between time since stroke and severity of neglect in a sample of 104 right CVA patients who were all at least 2 months post-stroke.

Denes, Semenza, Stoppa and Lis (1982) found that of 8 out of 24 RBD patients showing neglect on a cross-copying task given a mean of 50 days after their CVA, 7 still showed neglect 6 months later. Of the 5 out of 24 left brain-damaged patients who showed neglect initially, however, only 2 were still neglecting at 6 months. Kinsella and Ford (1985) reported that of eight patients showing neglect initially, four still showed it 18 months later. Robertson, Gray, Pentland, & Waite (1990) found that of 36 patients showing left neglect a mean of 15 weeks post-stroke, 73% (19 of the 26 who could be followed up) of those followed up a further 6 months later still showed clinically significant neglect.

It seems, therefore, that recovery from neglect is poor if subjects are first assessed in the post-acute phase following stroke (more than 2–3 months post-CVA). This contrasts with the relatively rapid remission in the acute phase. This fact will be discussed in the light of data examining non-lateralised attentional deficits in neglect.

Evidence for Attentional Deficits Within Ipsilesional Hemispace in Unilateral Neglect

Weintraub and Mesulam (1987) analysed search times in a cancellation test and found that right brain-damaged patients not only had longer search times on the left than controls and left brain-damaged patients, but also had longer right search times even than the left brain-damaged patients, for whom this was their impaired side. They suggested that this is attributable to the right hemisphere having an attentional role for both sides of space, resulting, in the case of damage to this hemisphere, in both bilateral and unilateral attentional deficits.

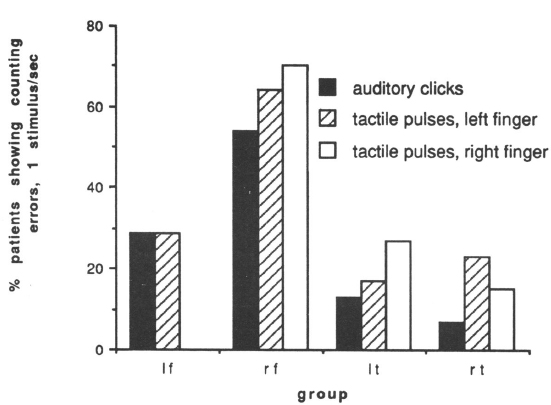

Some commentators (Gainotti, Giustolisi, & Nocentini, 1990) have argued that these results are open to an alternative explanation, namely that patients can often neglect with respect to some retintopically based midline which may not be related to the midline of the entire text. For example, in a densely packed visual task such as that used by Weintraub and Mesulam, what may be neglected may relate to a constantly shifting midline within a correspondingly moving narrow attentional field, even when the person is searching to the right side of the stimulus array. By this argument, omissions on the ipsilesional side may reflect simple lateralised neglect of localised areas of the target array. While this argument is an important one, it is not uncommon to observe left neglect patients who neglect at the very right extremity of the stimulus array. Figure 12.3 shows the cancellation performance of such a patient. Such results are difficult to explain by a model of deficit calling on purely lateralised deficits in attention.

Fig. 12.3. Example of cancellation omissions on the extreme right in a case of unilateral left neglect.

Robertson (1989) also proposed a non-lateralised attentional deficit in unilateral left visual neglect, and predicted that one result of this would be a significant increase in right-sided omissions as compared with controls when left neglect patients were cued to the left (in this case by being required to read a simple word under the left stimulus location at the same time as detecting the target stimuli) during the presentation of rapid single or double stimuli. This prediction was substantiated, with left cueing resulting in the equalising of left vs right errors among the left neglect patients.

Halligan and Marshall (1990) have shown in a case of unilateral neglect that not only is the displacement of line bisection greater to the right than in normals, but that the standard deviations of displacements of deviations is much greater than in normals. They therefore attribute unilateral neglect to the result of a combination of two distinct impairments: a consistent right-to-left approach to an “indifference zone” or approximate area of perceived middle of the line, and a greater Weber fraction (“a stimulus must be increased by a constant fraction of its value to be just noticeably different”). In other words, there is, apart from the lateralised deficit, a non-lateralised deficit in perceptual estimation which leads to a bigger margin of error in the bisection judgements of this neglect subject.

Evidence for Increased Neglect with Increased Demands Upon Attention

Robertson (1990) found that degree of neglect was highly correlated with the discrepancy between forward and backward digit span. The authors of a previous study which showed this (Weinberg, Diller, Gerstman, & Schulman, 1972) concluded that this reflected a deficit in visuo-spatial representation of the numbers. This conclusion rested, however, on the untested assumption that using a visuo-spatial strategy for the task is advantageous.

The validity of this assumption is cast in doubt by a study by Brooks and Byrd (1988), who showed that giving normals an imagery instruction to visualise the numbers while carrying out digit backward span produced no improvement in performance. This assumption is also challenged by the fact that Robertson (1990) showed that the Paced Auditory Serial Addition test, a test of information processing with no plausible spatial component, was almost as highly correlated with degree of neglect as was the digit discrepancy score. Furthermore, the digit discrepancy score independently predicted a proportion of the variance in neglect even when visuo-spatial capacity (measured by a line orientation test) was partialled out in a multiple-regression. Also, other indices of possible mental deterioration such as verbal memory or perseveration were uncorrelated with degree of neglect, and hence the relationship appears not to be a simple byproduct of severity of brain damage.

All this suggests that the finding of a relationship between severity of neglect on the one hand and digit discrepancy on the other cannot be attributed to lateralised or spatial factors. That digit discrepancy is a valid measure of attentional capacity is supported not only by its correlation with the Paced Auditory Serial Addition test in the present study, but also by the work of Das and Molloy (1975), who showed that backward digit span required a “simultaneous processing” capacity more attentionally demanding than forward digit span.

Rapcsak, Verfaellie, Fleet and Heilman (1989) examined the degree of left hemi-inattention shown by a group of patients in a simple cancellation task under three conditions. The first required the patient to cancel all of a group of simple stimuli. The second required cancellation of only those of a group of similar stimuli which differed from the other stimuli by one simple feature—a “dot” in the top right- or left-hand corner. In the third condition, the stimulus to be cancelled had a dot in the top right- or left-hand corner but, in addition to the foils used in the first condition, there were additional foils which had a dot in the bottom right- or left-hand corner which were also to be ignored. The last condition differed from the other two only in that it required more selective attention from the subjects, i.e. the subjects had to select stimuli from among a greater variety of competing choices. The authors found that the degree of neglect in the latter condition was significantly greater than in the other two, suggesting a deterioration in hemi-inattention under greater non-lateralised attentional load. This finding has subsequently been replicated (Kaplan et al., 1991).

Robertson and Frasca (1992) studied the effect of engaging in an attentionally demanding secondary task (counting backwards in threes from 100) while carrying out a simple visual detection task for briefly presented stimuli. In two out of four patients with left neglect, the latency of response for left stimuli significantly lengthened in comparison to that for right stimuli. An obvious problem with this study, however, is that the “activation” task was primarily verbal and hence by Kinsbourne’s theory (see Chapter 3, this volume), the left hemisphere activation should skew attention further to the right, producing the effect attributed in this paper to dual-tasking. In one of these two patients, there was in fact no left-right difference in latency in the non-counting condition, but one emerged when the attentionally demanding secondary task was added.

Evidence for Relatively Greater Difficulty with Conjunction Versus Feature Search Among Neglect Subjects

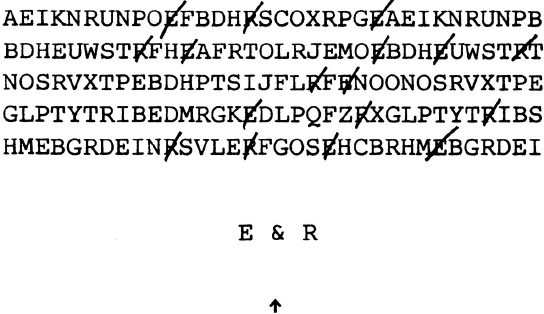

Eglin, Robertson and Knight (1989); (see also Chapter 8, this volume) have shown that serial (conjunction) search is more compromised in unilateral neglect than is feature search. Figure 12.4 shows results from this study, indicating that searching for stimuli defined by “conjunctions” of basic perceptual features (requiring serial, focused attention) was much more impaired on the left compared to the right than was search for stimuli defined by basic perceptual features.

Fig. 12.4. Feature vs conjunction search in unilateral neglect. Reprinted from Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 1, (4), Eglin et al. (1989), “Visual search performance in the neglect syndrome”, by permission of the MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Riddoch and Humphreys (1987) had previously demonstrated the same result. It must be noted, however, that feature search is not spared; neither is it parallel, as it is in normals, as evidenced by the slight slope on the feature search curve in Fig. 12.4.

Evidence for Influence of Degree of Arousal Upon Neglect

Fleet and Heilman (1986) compared the performance of neglect patients on repeated letter cancellation administrations under two conditions—one with feedback of results, one with no feedback. The feedback consisted simply of them being told the number of errors they had made after each cancellation trial. With serial administrations in a short time period, neglect increased in the no-feedback condition, but decreased in the feedback condition. The authors interpret this as being due to improved arousal as a result of feedback of results, causing a reduction in neglect, though of course other interpretations are possible, and the phenomenon cannot unequivocally be attributed to increased arousal.

The apparent association between unilateral neglect and non-laterialised attentional difficulties outlined in the studies just reviewed can now be set in the context of studies of hemispheric lateralisation of attentional function.

Evidence for a Right Hemisphere Specialisation for Certain Aspects of Attention

The following review of a right hemisphere specialisation for certain aspects of attention cannot be exhaustive because of the large number of studies dealing with this issue. The following brief review is therefore highly selective.

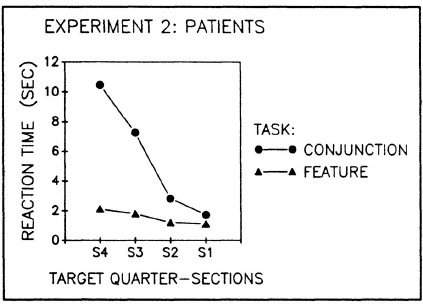

Howes and Boller (1975) compared unwarned reaction times to auditory stimuli in left vs right CVA subjects, who were matched in terms of size of brain lesion (in fact, the right CVAs had on average slightly smaller lesions). They found that the reaction times of the right CVA group were almost twice those of the left CVA groups (see Fig. 12.5).

Fig. 12.5. Simple unwarned auditory reaction times in right CVA, left CVA and aged-matched controls (based on data in Howes & Boller, 1975).

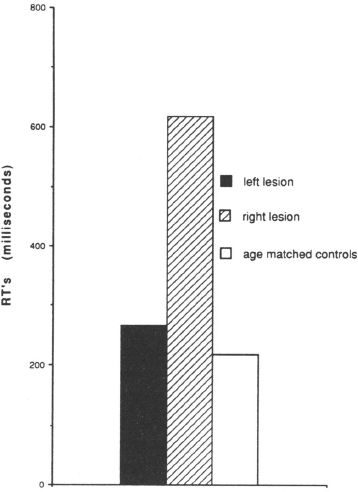

Wilkins, Shallice and McCarthy (1987) showed that right frontal lesioned patients showed significantly more errors than left frontal, left temporal or right temporal groups in their capacity to accurately count stimuli appearing at a rate of one per second. The stimuli consisted of auditory clicks and tactile pulses to the right and left index fingers, respectively (see Fig. 12.6). The results showed that right frontal lesioned patients were particularly poor at sustaining the attention required to count the pulses, whether auditory or tactile, when these pulses occurred at a rate of one per second. In contrast, they were not differentially impaired (in terms of their % deviation from the true value) when the rate of presentation was increased to seven per second. The authors argue that this is evidence for a deficit in sustained attention associated with right frontal lesions, as the one per second task is more demanding of this type of attention than is the seven second per task.

Fig. 12.6. Errors in counting by lesion group (based on data in Wilkins et al., 1987).

Coslett, Bowers and Heilman (1987) compared auditory unwarned reaction time performance in right and left CVA subjects under two experimental conditions: one in which the reaction time task was performed on its own and one in which it was performed in conjunction with a second task. The authors argued for a right hemisphere dominance for mediating arousal and hence predicted poorer dual-task performance in right than left brain damage. The results confirmed this. When the second task was added (sorting coins), the mean reaction times (RTs) of the left brain-damaged group rose from 0.3 to 0.5 sec. However, the RTs of the right brain-damaged group rose from 0.5 to 1.3 sec under the dual-task condition. This interaction was statistically significant and could not be attributed to lesion size effects. Half of the right brain-damaged patients showed neglect, whereas all of the left brain-damaged patients were aphasic.

Sandson and Albert (1987) have shown that right brain-damaged patients show significantly more perseveration on tasks such as writing alternative cursive letters (m and n) than do left brain-damaged aphasics or controls. They have also reported a high incidence of perseveration on cancellation shown by neglect patients. Heilman and Van Den Abell (1979) showed that, in normals, lateralised warning stimuli projected to the right hemisphere before a central stimulus reduced RTs significantly more than stimuli projected to the left hemisphere, suggesting a role for phasic activation for the right hemisphere. Heilman, Schwartz and Watson (1978) found that stimulating the ipsilesional arm with an electrode produced lower galvanic skin responses (GSRs) among right brain-damaged patients with neglect than among left brain-damaged aphasics or normals. In contrast, left brain-damaged aphasics showed higher GSRs than normals. This suggested a particular role for the right hemisphere in modulating arousal. Finally, Posner, Inhoff, Friedrich and Cohen (1987) showed that patients with right parietal lesions were greatly affected when a cue was omitted before a target, whereas those with left parietal lesions were not, and deduced from this that patients with right-sided lesions have a particular problem with maintaining alertness.

In conclusion, it appears that the right hemisphere has a particular role in one particular aspect of attention, namely that class of faculties variously described as “alertness”, “vigilance”, “arousal”, and (perhaps) “sustained attention”. Given the evidence of Wilkins et al. (1987) that the right frontal lobe is implicated in particular in the maintenance of this function, what is the evidence that the frontal lobes in turn are implicated in neglect?

Vallar (Vallar & Perani, 1986; see also Chapter 2, this volume) reports that a variety of cortical and subcortical lesions may be associated with neglect, including the frontal lobes (e.g. Heilman & Valenstein, 1972), though the inferior parietal lobe is much more commonly associated with the neglect syndrome. He also notes how neglect may be correlated with diaschisis-type hypoperfusion in areas of the brain quite distant from, though connected with, the structurally damaged areas.

Kertesz and Dobrowolski (1981) showed that both neglect and perseveration were significantly worse in patients with frontal and extensive central lesions. Hier at al. (1983b, p. 349) reported that “recovery from constructional apraxia, unilateral spatial neglect on drawing and extinction was more rapid in patients without injury to the right frontal lobe”. In contrast, Egelko et al. (1988) found that while neglect seldom occurred in patients with lesions to a single lobe of the brain (based on CT scans), neither frontal nor parietal regions were any more associated with the presence of inattention than were temporal or occipital lesions. They did, however, find an association between lesions in the basal ganglia and unilateral neglect, and there are very strong anatomical connections between the basal ganglia and frontal lobes. They also found that the size of the lesion was correlated with the degree of neglect, a finding also reported by Hier, Mondlock and Caplan (1983a).

There is therefore a small amount of evidence that recovery from neglect may be increased if the right frontal lobe is relatively spared by the lesion, though this can only remain a hypothesis given the present state of the evidence. What is clear, however, is that neglect is associated with large lesions involving several different areas of the brain, and therefore it is at least plausible that more than one attention system may be implicated in chronic neglect. Posner and Peterson’s three-factor model of attention will now be considered in the light of this evidence.

Posner and Peterson’s Model of Attention

According to Posner and Peterson (1990), three interrelated mechanisms, operating semi-autonomously, underlie attention in humans. These are orienting, target detection and alerting. Orienting is said to be based in a posterior attentional system, based largely in the posterior parietal lobe, the superior colliculus and the lateral pulvinar nucleus of the posterolateral thalamus, among other areas. Its function is to disengaged from, move to and engage attention to, high-priority stimuli. The right hemisphere is specialised for attention to low spatial frequency stimuli, leading to better detection of large “Gestalt” forms. The left hemisphere is specialised for high spatial frequency “micro” stimuli.

Target detection involves the focal or conscious attention system, which is closely related, functionally and anatomically, to the posterior attention system. It is related to target search and recognition (other than automatic recognition, e.g. of automatically detected word forms), and is to some extent related reciprocally to the third category of attention, alerting. Its anatomical basis is possibly the anterior cingulate and supplementary motor areas. Posner and Peterson suggest a possible hierarchy of attentional systems, with the anterior system delegating to the posterior one when it is not occupied with processing other material.

Alerting or vigilance is a system for preparing the brain for processing high-priority signals. It does not improve the processing of the signals, but increases the rate at which attention can respond to stimuli. The right hemisphere—possibly the right prefrontal cortex—appears, according to Posner and Peterson, to be specialised for this, namely for vigilance-type tasks.

Noradrenaline may be the mechanism for alerting, and there is some evidence for a right hemisphere bias in the NA system, and that it is stronger in the frontal cortex, to where it goes first from the locus coeruleus before spreading back into the parietal areas. Hence the alerting system is particularly strong in its effects on the posterior attention system of the right hemisphere. Functionally, the alerting system acts through the posterior system to increase the rate at which high-priority information can be selected for further processing.

Overview and Hypothesis

The evidence reviewed above on the role of non-lateralised attentional deficits associated with (mainly left) unilateral neglect can be related to Posner and Peterson’s model to explain the apparent paradox of neglect recovery outlined at the beginning of the chapter, namely the differential recovery rates for acute and chronic neglect patients on the one hand, and left vs right neglect on the other. The hypothesis suggests that for neglect to be manifest in the acute phase following brain injury, damage to the posterior orientation system may be sufficient. This would explain why the incidence of neglect in right and left brain-damaged patients is more similar in the acute than in the chronic phase, since Posner and Peterson do not suggest any asymmetry in lateralisation of the right and left orientation systems.

It must be noted, however, that Kinsbourne (Chapter 3, this volume) and Robertson and Eglin (Chapter 8. this volume) propose an alternative possible explanation for the right hemisphere preponderance of neglect, drawing on the fact that the left hemisphere is responsible for local vs global processing. By this argument, the damaged right hemisphere will lead to a reduction in representation of global forms and to a relative strengthening of representation of local forms. Given that there are by definition more of the latter, the right brain-damaged subject will be confronted with a greater number of stimuli to scan on the ipsilesional side, resulting in a greater degree of neglect of the left side. While this argument accommodates some of the data reviewed above, it does not explain fluctuations in neglect according to attentional factors which are independent of the visual field.

Weintraub and Mesulam (1987), among others, suggest another reason for the right hemisphere preponderance of neglect, i.e. that the right hemisphere has bilateral attentional responsibilities, resulting in bilateral deficits. Such a view implies impairment in quite basic attentional processes and does not rest easily with those findings mentioned above that higher level attentional processes may be implicated in neglect. Furthermore, several studies have failed to establish in normals that the left and right hemispheres differ in their attentional responsibilities in the way that Weintraub and Mesulam describe (e.g. Roy et al., 1987).

The defective vigilance hypothesis is therefore still a strong contender for explaining the low incidence of right neglect. Turning to how recovery from neglect takes place, one can argue that most patients learn spontaneously to compensate for the inattention caused by damage to the posterior attentional system in ways which will be discussed below. However, those patients who have large right hemisphere lesions are also more likely to show deficits in a second attentional system, namely the arousal or vigilance system. By this argument, they do not learn to compensate for the skewed attention of the posterior orientation system, because arousal and vigilance deficits impair the learning of compensatory strategies which in other patients result in improvements in neglect.

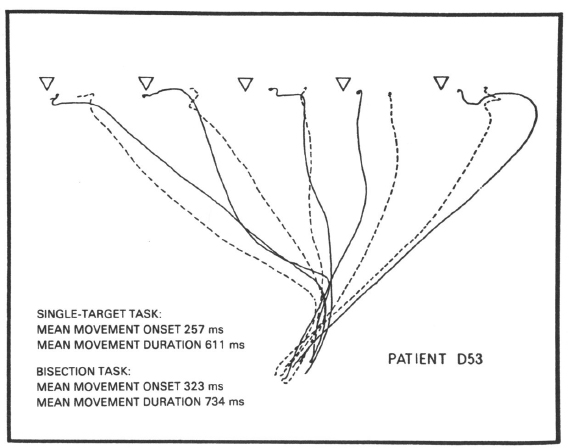

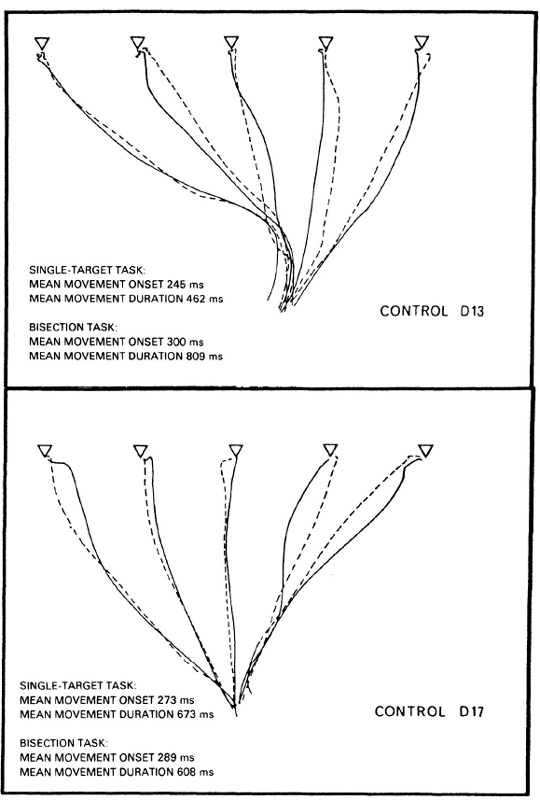

What is the evidence that neglect patients recover by such hypothetical compensatory mechanisms? A study by Goodale, Milner, Jakobson and Carey (1990) provides some relevant evidence. They studied a group of nine subjects who had suffered unilateral right hemisphere lesions a mean of 21 weeks after the onset of the lesion. Many of these patients had previously shown signs of unilateral neglect, but by the time they were tested by the authors, there was no clinically significant neglect. The experiment consisted of two tasks, one involving reaching out and touching one of a number of lighted targets presented on a vertical screen in front of the subjects, and the other consisted of requiring the subjects to bisect the distance between two specified targets on the screen.

The brain-damaged patients showed no difference from the controls on their accuracy of touching the targets, while they did show a significant tendency to bisect to the right of the true midpoint of the distance between adjacent targets, suggesting the existence of an enduring subclinical manifestation of left unilateral neglect which was not revealed by standard clinical testing. More interesting, however, were the trajectories of the hand as it reached in to the targets. In both the target and bisection conditions, kinematic video analysis of the reaching movements was made. This revealed that the patients made a wide right arc into the final target, a pattern which was not apparent in the controls. Figure 12.7 shows the movements of patient D53 of the Goodale et al. series during detection as well as bisection of the distances between targets. Figure 12.8 shows the pathways of two control subjects.

Fig. 12.7. Limb trajectories of a right brain-damaged subject while reaching out to touch a target. From Goodale et al. (1990). Copyright 1990. Canadian Psychological Association. Reprinted with permission.

Fig. 12.8. Limb trajectories of two control subjects while reaching out to touch a target. From Goodale et al. (1990). Copyright 1990. Canadian Psychological Association. Reprinted with permission.

These results suggest that even after the apparent recovery of neglect, underlying distortions in spatial or attentional mechanisms still exist (for instance, the deficit may have been attributable to a persisting “hypokinesia”, namely a difficulty in making movements in the contralesional direction). It may be the case that the patients had learned to compensate for their neglect by compensatory visual control. When the patients first sent their arms out on ballistic trajectories, it appears that they did so on the basis of a distorted body-referenced spatial system. The rightward trajectory may then have been corrected by a compensatory visual feedback system, which the subjects had spontaneously learned to use to correct the spatial errors of which they may have been aware. Alternatively, they may not have been aware of the deficits, and these compensatory visual responses may have been elicited by some kind of conditioning process along the lines of those which have been hypothesised in hemianopics spontaneously learning to compensate for their visual field deficits (e.g. Meienberg et al., 1980; Williams & Gassell, 1962).

If it is true that underlying deficits still persist which are obscured by compensatory mechanisms, then it should be possible to cause the basic deficit to re-emerge by presenting a task which is attentionally demanding or requires a high degree of spatial thought. An example of the former may be the results for a case reported in Robertson and Frasca (1992), where left-right differences in response latency only emerged during an attentionally demanding secondary task performance. An example of the latter may be the poor performance of Goodale and co-workers’ subjects on the bisection task compared to the target pointing task.

There are important rehabilitation implications for the above arguments but these are discussed elsewhere in this volume (see Chapter 13).

Coda

Shallice (1988) and Posner et al. (1987) have argued that a general-purpose limited-capacity attentional system impairment cannot be what is impaired in unilateral neglect, on the basis of the valid/invalid cue paradigm developed by Posner. This paradigm involves testing patients on a reaction time task, where stimuli are presented to the left or right in a random fashion (Posner, Cohen, & Rafal, 1982). Some stimuli are preceded by a cue, which indicates on which side the stimulus will appear, and in a minority of trials this cue is “invalid”, i.e. it indicates the wrong side. Posner et al. demonstrated that subjects with parietal lesions were particularly impaired when they were invalidly cued to the ipsilesional side, with the target appearing on the contralesional side. They argued that a fundamental deficit in neglect is a deficit in a parietal lobe based “disengagement” mechanism, whereby there is difficulty in disengaging in the contralesional direction. Left and right parietal patients did not differ in the extent to which they exhibited this phenomenon.

Posner et al. (1987) studied nine patients with parietal lesions due to CVA, four with left parietal and five with right parietal damage. They compared the performance of these patients on the reaction time paradigm just described under normal conditions vs under conditions of a secondary task. If the disengagement attentional system is part of a wider “awareness” or general-purpose limited-capacity attentional system, then addition of the secondary task should cause a more marked disengagement difficulty for invalid cues than normal. Posner et al. did not, however, find this: The secondary task (phoneme monitoring) increased reaction times in both the valid and invalid trials by roughly the same amount.

Shallice and Posner conclude from this that the visual orienting system functions independently of a general-purpose limited-capacity attentional system. How does this square with the hypothesis advanced in the present chapter? First, it should be noted that of the nine subjects in Posner and co-workers’ (1987) study, only one showed any signs of visual neglect at the time of testing and two of the subjects were more than 5 years post-stroke. It is possible, therefore, that what the valid/invalid cue paradigm yielded was a subclinical sign of a lasting underlying deficit comparable with Goodale and co-workers’ (1990) limb-movement pattern described above. Such a deficit is almost certainly part of a spatial orienting system which is independent of a general purpose limited-capacity attentional system, and so it should not be surprising to find no differential effect of secondary task on valid and invalid trials with the kinds of subjects studied by Posner et al. (1987).

However, such a disengagement deficit is probably not, on its own at least, a sufficient deficit to account for the full florid phenomenon of unilateral neglect, at least in the chronic stage. By the argument of the present chapter, simultaneous damage to the orienting/disengagement and vigilance systems is required for unilateral neglect to persist. Hence in subjects for whom this is the case, then secondary tasks should exacerbate neglect, as has been demonstrated in many of the studies described above.

In short, very different conclusions may be derived about the nature of unilateral neglect depending upon the chronicity of the subjects studied. This factor has not sufficiently been taken into account in the neglect literature.

References

Brooks. D.A. & Byrd, J. (1988). The effect of internal visualization on digit span performance. International Journal of Neuroscience, 43, 145–147.

Coslett, H.B., Bowers, D., & Heilman, K.M. (1987). Reduction in cerebral activation after right hemisphere stroke. Neurology, 37, 957–962.

Das, J.P. & Malloy, G.N. (1975). Varieties of simultaneous and successive processing in children. Journal of Educational Psychology, 67, 213–220.

Denes, G., Semenza, C., Stoppa, E., & Lis, A. (1982). Unilateral spatial neglect and recovery from hemiplegia: A follow-up study. Brain, 105, 543–552.

Egelko, S., Gordon, W.A., Hibbard, M.R., Diller, L., Lieberman, A., Holliday, R., Ragnarsson, K., Shaver, M.S., & Orazem, J. (1988). Relationship among CT scans, neurological exam and neuropsychological test performance in right brain damaged stroke patients. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 10, 539–564.

Eglin, M., Robertson, L.C., & Knight, R.T. (1989). Visual search performance in the neglect syndrome. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 1, 372–385.

Fleet, W.S. & Heilman, K.M. (1986). The fatigue effect in unilateral neglect. Neurology, 36, 258 (suppl. 1).

Gainotti, G., Giustolisi, L., & Nocentini, U. (1990). Contralateral and ipsilateral disorders of visual attention in patients with unilateral brain damage. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, 53, 422–426.

Goodale, M.A., Milner, A.D., Jakobson, L.S., & Carey, D.P. (1990). Kinematic analysis of limb movements in neuropsychological research; Subtle deficits and recovery of function. Canadian Journal of Psychology, 44, 180–195.

Halligan, P.W., Manning, L., & Marshall, J.C. (1990). Individual variation in line bisection: A study of four patients with right hemisphere damage and normal controls. Neuropsychologia, 28, 1043–1051.

Halligan, P.W. & Marshall, J.C. (1990). Line bisection in a case of visual neglect; Psychophysical studies with implications for theory. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 7, 107–130.

Heilman, K.M., Schwartz, H.D., & Watson, R.T. (1978). Hypoarousal in patients with the neglect syndrome and emotional indifference. Neurology, 28, 229–232.

Heilman, K.M. & Valenstein, E. (1972). Frontal lobe neglect in man. Neurology, 22, 660–664.

Heilman, K.M. & Van Den Abell, T. (1979). Right hemisphere dominance for mediating cerebral activation. Neuropsychologia, 17, 315–321.

Hier, D.B., Mondlock, J., & Caplan, L.R. (1983a). Behavioral abnormalities after right hemisphere stroke. Neurology, 33, 337–334.

Hier, D.B., Mondlock, J., & Caplan, L.R. (1983b). Recovery of behavioural abnormalities after right hemisphere stroke. Neurology, 33, 345–350.

Howes, D. & Boller, F. (1975). Simple reaction time: Evidence for focal impairment from lesions of the right hemisphere. Brain, 98, 317–332.

Kaplan, R.F., Verfaillie, M., Meadows, M.E., Caplan, L.R., Peasin, M.S., & De Witt, D. (1991). Changing attentional demands in left hemispatial neglect. Archives of Neurology, 48, 1263–1266.

Kertesz, A. & Dobrowolski. S. (1981). Right-hemisphere deficits, lesion size and location. Journal of Clinical Neuropsychology, 3, 283–299.

Kinsella, G. & Ford, B. (1985). Hemi-inattention and the recovery patterns of stroke patients. International Rehabilitation Medicine, 7, 102–106.

Meienberg, O., Zangmeister, W., Rosenberg, M., Hoyt, W., & Stark, L. (1980). Saccadic eye movement strategies in patients with homonymous hemianopia. Annals of Neurology, 9, 537–544.

Posner, M.I., Cohen, Y., & Rafal, R.D. (1982). Neural systems control of spatial orienting. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, B298, 187–198.

Posner, M.I., Inhoff, A., Friedrich, F.J., & Cohen, A. (1987). Isolating attentional systems: A cognitive-anatomical analysis. Psychobiology, 15, 107–121.

Posner, M.I. & Peterson, S.E. (1990). The attention system of the human brain. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 13, 25–42.

Rapscak, S.Z., Verfaellie, M., Fleet, S., & Heilmann, K.M. (1989). Selective attention in hemispatial neglect. Archives of Neurology, 46, 172–178.

Riddoch, M.J. & Humphreys, G.W. (1987). Perceptual and action systems in unilateral visual neglect. In M. Jeannerod (Ed.), Neurophysiological and neuropsychological aspects of neglect. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Robertson, I. (1989). Anomalies in the lateralisation omissions in unilateral left neglect: Implications for an attentional theory of neglect. Neuropsychologia, 27, 157–165.

Robertson, I. (1990). Digit span and visual neglect: A puzzling relationship. Neuropsychologia, 28, 217–222.

Robertson, I. & Frasca, R. (1992). Attentional load and visual neglect. Intemational Journal of Neuroscience, 62, 45–56.

Robertson, I., Gray, J., Pentland, B., & Waite, L. (1990). Microcomputer-based rehabilitation of unilateral left visual neglect: A randomised controlled trial. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 71, 663–668.

Roy, E., Reuter-Lorenz, P., Roy, L., Copland, S., & Moscovitch, M. (1987). Unilateral attention deficits and hemispheric asymetries in the control of attention. In M. Jeannerod (Ed.), Neurophysiological and neuropsychological aspects of neglect. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Sandson, J. & Albert, M.L. (1987). Perseveration in behavioural neurology. Neurology, 37, 1736–1741.

Shallice, T. (1988). From neuropsychology to mental structure. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Stone, S.P., Wilson, B., Wroot, A., Halligan, P.W., Lange, L.S., Marshall, J.C., & Greenwood, R.J. (1991). The assessment of visuo-spatial neglect after acute stroke. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, 54, 345–350.

Vallar, G. & Perani, D. (1986). The anatomy of unilateral neglect after right hemisphere stroke lesions: A clinical CT/scan correlation study in man. Neuropsychologia, 24, 609–622.

Weinberg, J., Diller, L., Gerstman, L., & Schulman, P. (1972). Digit span in right and left hemiplegics. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 28, 361.

Weintraub, S. & Mesulam, M. (1987). Right cerebral dominance in spatial attention: Further evidence based on ipsilateral neglect. Archives of Neurology, 44, 621—625.

Wilkins, A.J., Shallice, T., & McCarthy, R. (1987). Frontal lesions and sustained attention. Neuropsychologia, 25, 359–365.

Williams, D. & Gassell, M. (1962). Visual function in patients with homonymous hemianopia. Part 1. The visual fields. Brain, 85, 175–250.

Zarit, S. & Kahn, R. (1974). Impairment and adaptation in chronic disabilities: Spatial inattention. Journal of Nervous and Mental Diseases, 159, 63–72.

Zoccolotti, P., Antonucci, G., Judica, A., Montenero, P., Pizzamiglio, L., & Razzano, C. (1989). Incidence and evolution of the hemineglect disorder in chronic patients with unilateral right brain damage. International Journal of Neuroscience, 47, 209–216.