Chapter 5 Gender and Communication

Outline

Verbal and nonverbal communication are at the core of human psychology, essential to our social interactions and relationships as well as to our thoughts and understanding of the world. In this chapter we will explore the evidence on the differences between how women and men communicate verbally and nonverbally, and on how women and nonbinary people are treated in language. We will also provide practical guidance on using inclusive, nonsexist language.

Verbal Communication

Suppose you found the following caption, torn from a cartoon: “That sunset blends such lovely shades of pink and magenta, doesn’t it?” If you had to guess the gender of the speaker, what would you say? Most people would guess that the speaker was a woman. Many people have ideas about what is typical or “appropriate” speech for men and women, and lovely and magenta just don’t sound like things a man would say. Are those ideas just inaccurate gender stereotypes, or is there some kernel of truth to them? Do women and men actually differ in their verbal communication?

Tentativeness

The study of gender differences and similarities in language was sparked by Robin Lakoff (1973, 1975), who theorized that gender differences in communication stem from gender roles and the relative power those roles have. In other words, women and men don’t differ in communication because they are innately different from one another, but because the social hierarchy makes them different. She argued that men use more assertive speech because they have power, whereas women use more tentative speech because they lack power.

What does tentative speech look (or sound) like? According to Lakoff, tentative speech has four forms or patterns: expressions of uncertainty, hedges, tag questions, and intensifiers. Expressions of uncertainty include disclaimers, like “I may be wrong, but . . .” or “This is just my opinion, but. . . .” Hedges are expressions such as “sort of” or “kind of.” A tag question is a short phrase at the end of a declarative sentence that turns it into a question, such as “This is a great class, isn’t it?” And intensifiers include adverbs like very, really, and vastly, such as “The governor is really interested in this proposal.” Lakoff maintained that intensifiers add little content to a sentence and actually reduce the strength of the statement, so they contribute to tentativeness.

Lakoff’s theorizing gained popularity as well as criticism in part because it highlighted a tension within feminism regarding gender differences and gender similarities. That is, if women and men are equal, does that mean that women and men are exactly the same? If women and men are different, how does patriarchal culture create those differences? Thus, it’s not surprising that critics said Lakoff exaggerated and overemphasized gender differences without giving adequate attention to power and status. Similarly, some criticized her theory because it seemed to reflect gender stereotypes rather than empirical evidence. Her theory also implies, for some, a female deficit interpretation in labeling women’s communication as deficient in respect to men’s communication, which is held up as the standard. That is, maybe tentative speech can be more effective speech, reflecting interpersonal sensitivity.

What do the data show? Campbell Leaper and Rachael Robnett (2011) conducted a meta-analysis to examine the evidence for gender differences in the four forms of tentative speech. Overall, they found that women used more tentative speech but that the gender differences were small. For expressions of uncertainty, such as disclaimers, d = −0.33, and for hedges, d = −0.15. For tag questions, d = −0.23, and for intensifiers, d = −0.38. In sum, the pattern of gender differences in tentative speech supports Lakoff’s claim, but those differences are small.

In addition, Leaper and Robnett (2011) interpreted the results of their meta-analysis to mean that women display greater interpersonal sensitivity, not that they lack assertiveness. If gender differences in tentative speech reflect issues of power and assertiveness, then they should be largest in mixed-gender groups, with men dominating and women being tentative. Yet gender differences in tentative speech were actually larger in same-gender groups (d = −0.37) than in mixed-gender groups (d = −0.21). Thus, we might say that the tag question is intended to encourage communication rather than to shut things down with a simple declarative statement. The tag question helps maintain the conversation and encourages the other person to express an opinion.

Affiliative Versus Assertive Speech

As the data evaluating Lakoff’s theory accumulated, linguist Deborah Tannen popularized the belief that women’s and men’s communication patterns are vastly different and that these differences create problems when women and men communicate with one another. In her widely read books, including You Just Don’t Understand: Women and Men in Conversation (Tannen, 1991), she proposed that gender differences in communication are so substantial that it is as though women and men come from different linguistic communities or cultures. Thus, communication between women and men is as challenging as communication between people from different cultures—say, a person from the United States and a person from Japan. Tannen’s position is called the different cultures hypothesis.

Photo 5.1 According to the theorist Robin Lakoff, we should expect these two social groups to differ in the amount of disclaimers, hedges, and tag questions. Do you interpret that gender difference as evidence of women’s greater tentativeness or interpersonal sensitivity?

©iStockphoto.com/kali9 & ©iStockphoto.com/digitalskillet.

Tannen’s perspective differed from Lakoff’s in an important way: Whereas Lakoff theorized that gender differences develop because of men’s power over women, Tannen claimed that gender differences in communication stem from the different goals that men and women have when they communicate. These different communication goals are rooted in gender roles. The female role emphasizes nurturing and relationships, whereas the male role emphasizes dominance and power. Thus, these roles require that women aim to establish and maintain relationships, whereas men aim to exert control, preserve their independence, and enhance their status (Tannen, 1991; J. T. Wood, 1994). Women try to show support or empathy by matching or mirroring experiences (“I’ve felt that way, too”), whereas men try to display their knowledge, avoid disclosing personal information, and avoid showing the slightest vulnerability. Women engage in conversation maintenance, trying to get a conversation started and keep it going (“How was your day?”), whereas men engage in conversational dominance (e.g., interrupting). Tannen claimed that women display tentative and affiliative speech, whereas men display assertive and authoritative speech.

Thus, another perspective on gender differences in verbal communication is Tannen’s different cultures hypothesis. To evaluate it, we can examine gender differences in affiliative and assertive speech. Affiliative speech is speech that demonstrates affiliation or connection to the listener and may include praise, agreement, support, and/or acknowledgment. By contrast, assertive speech is speech that aims to influence the listener and may include providing instructions, information, suggestions, criticism, and/or disagreement. Note that some speech could be both assertive and affiliative, such as when someone gives instructions that are supportive (e.g., “You seem tired; go and get some rest”).

Leaper and his colleagues have conducted two meta-analyses that examine gender differences in affiliative and assertive speech, one with children and one with adults. Let’s first consider affiliativeness. In general, girls and women are somewhat more affiliative relative to boys and men. Among children, the gender difference is small, d = –0.26 (Leaper & Smith, 2004). That gender difference shrinks in adulthood, d = –0.12 (Leaper & Ayres, 2007).

With regard to assertiveness, the gender differences are tiny. Among children, boys engage in more assertive speech than girls do, but the difference is very small, d = 0.10 (Leaper & Smith, 2004). Among adults, men are slightly more assertive than women, d = 0.09 (Leaper & Ayres, 2007). Thus, evidence suggests that male speech patterns are only marginally more assertive than female speech patterns.

In sum, the gender differences in affiliative and assertive speech are just too small to support the different cultures hypothesis. Apparently, cross-cultural communication is possible—girls and women can and do use assertive speech, just as boys and men can and do use affiliative speech!

Photo 5.2 According to linguist Deborah Tannen, women and men have different goals when they speak. Women aim to establish and maintain relationships, whereas men aim to exert control.

©iStockphoto.com/Wavebreakmedia.

Interruptions

Early researchers found that men interrupt women considerably more often than women interrupt men (e.g., C. West & Zimmerman, 1983; Zimmerman & West, 1975). For example, one important and widely cited study found that gender differences in interruptions are found only in mixed-gender conversation pairs (McMillan et al., 1977). That is, women interrupted women about as often as men interrupted men. However, women very seldom interrupted men, whereas men frequently interrupted women. How should we interpret this pattern of gender differences and similarities? The typical interpretation made by feminist social scientists involves the assumption that interruptions are an expression of power or dominance. That is, the interrupter gains control of a conversation, and that is a kind of interpersonal power. The gender difference, then, is interpreted as indicating that men are expressing power and dominance over women. This pattern may reflect the subtle persistence of traditional gender roles; it may also help to perpetuate traditional roles.

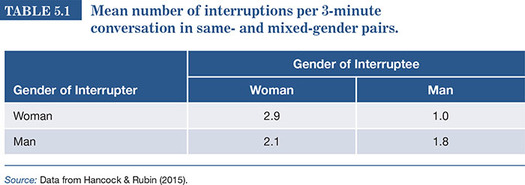

Yet one recent study found slightly different results (see Table 5.1; Hancock & Rubin, 2015). Across conversational pairs, women were more likely to be interrupted than men were, regardless of who was doing the interrupting. One interpretation of this finding, consistent with the feminist perspective, is that women are generally perceived as lower status and, thus, can be interrupted. Men, because they have higher status, are less likely to be interrupted.

Source: Data from Hancock & Rubin (2015).

Some researchers have suggested that interruptions can have multiple meanings, which complicates the interpretation of these gender differences (Aries, 1996; McHugh & Hambaugh, 2010). Some interruptions are requests for clarification. Others express agreement or support, such as an mm-hmm or definitely murmured while the other person is speaking. Some interruptions express disagreement with the speaker, and other interruptions change the subject. These last two types of interruptions are the ones that express dominance. Most interruptions in fact turn out to be agreements or requests for clarification and have nothing to do with dominance. Some researchers have found that women engage in more of this supportive interrupting, particularly when they are in all-female groups (e.g., Aries, 1996).

A meta-analysis of gender differences and similarities in conversational interruption provides us with some clarity on this controversy. Anderson and Leaper (1998) found that the gender difference in interruptions was d = 0.15, indicating that men interrupt more often than women. However, moderator analyses told a more complex story about interruptions. Effect sizes for intrusive interruptions (i.e., interruptions that display dominance, such as a change in subject or expression of disagreement) were considerably larger, d = 0.33.

Overall, then, to say that men interrupt more than women do, and that this indicates men’s expression of dominance, is not entirely accurate (Aries, 1996; McHugh & Hambaugh, 2010). Patterns of gender differences in interruption may vary depending on context (mixed-gender group vs. same-gender group, natural conversation vs. laboratory task), and interruptions can have many meanings besides dominance. For intrusive interruptions, however, men interrupt more often than women do.

The Gender-Linked Language Effect

As you’ve seen, many of the gender differences in verbal communication are unimpressive. Anthony Mulac (2006) proposed that, while many features of verbal communication show very small gender differences, it is the clustering of these features that matters. That is, there are feminine and masculine patterns of speech, each with multiple features that show subtle differences on their own but, in combination, are perceived as distinctly gendered. The verbal communication of girls and women tends to be rated as more socially intelligent and aesthetically pleasing, whereas the verbal communication of boys and men is rated as more dynamic and aggressive. Mulac calls these patterns of gender differences the gender-linked language effect.

Mulac (2006) conducted a series of studies in which the speech of men and women (or boys and girls) is transcribed, masked as to the identity of the speaker, and then presented to university students to see whether they can tell whether the speaker was male or female. If Tannen’s hypothesis is correct, the task should be a snap and students should be able to identify the gender of the speaker with a high degree of accuracy. In fact, though, students perform no better than chance on the task. These findings support the notion of gender similarities in communication.

Other studies, though, find significant differences between women’s and men’s speech when highly trained coders look for specific details such as intensifiers, tag questions, and references to emotions (Mulac, 2006). The differences must therefore be subtle, detectable by scientifically trained coders but not by the average person.

Mulac and his colleagues (2013) found some evidence of the gender-linked language effect in a recent study of written language. In the first task, participants wrote descriptions of landscape photographs and the research team coded those descriptions for 13 features of language that have been shown to differ between men and women. Only six of those features showed gender differences. For example, men tended to make more references to quantity (e.g., “60 feet tall”) and use elliptical sentences (e.g., “great picture”), whereas women tended to write more words overall and make more references to emotion (e.g., “a somber scene”). Many features of tentative language, such as hedges and intensifiers, showed gender similarities.

In the second task, the researchers asked the participants to write descriptions of more photographs, this time under the guise of specific genders. That is, participants were asked to describe the photographs “as a man” and “as a woman.” This task was used to indicate participants’ gender-linked language schemas. The results showed that schemas were somewhat consistent with the actual gender differences found in the first task: Gender differences in the second task matched four of the six features that showed gender differences in the first task, including references to quantity and emotion. In other words, participants had clear gender schemas about language, and these schemas were fairly accurate. These findings demonstrate that the gender-linked language effect exists but that the effect is subtle.

Clinical Applications

You might be wondering: How are the gender-linked language effect and other gender differences in verbal communication relevant? Well, there are at least two reasons that these findings matter. One reason is that language is often used to persuade, solve problems, and connect with people. Doing these things effectively requires using our language well. As discussed earlier, in some cases tentative language is more interpersonally sensitive and, therefore, more effective. As the old saying goes, you can catch more flies with honey than with vinegar.

Another reason the gender-linked language effect is relevant is in its clinical application, such as in the case of communication therapy. For transgender people, communication therapy is often a component of their transition. This therapy might include working with a speech-language pathologist to change such speech features as vocal pitch, resonance, intonation, volume, articulation, and others so that their speech is more aligned with their gender identity (Adler et al., 2012; Hancock et al., 2015). For example, a transgender woman might work with a therapist to speak in a higher vocal pitch and to alter her intonation so that some of her declarative statements end with a rise in pitch. Even if the differences in speech are subtle, they can improve the quality of social interactions and may help to prevent painful misgendering experiences in which others misidentify their gender identity.

Nonverbal Communication

Nonverbal communication is just as important as verbal communication. Imagine saying to someone “How nice to see you” while standing only 6 inches from them or while actually brushing up against them. Then imagine saying the same sentence while standing 6 feet away from them. The sentence conveys a much different meaning in the two instances. In the first, it will probably convey warmth and possibly sexiness. In the second case, the meaning will seem formal and perhaps cold. As another example, a sentence coming from a smiling face conveys a very different meaning from that of the same sentence coming from a stern or frowning face.

Focus 5.1 Gender and Electronic Communication

How we communicate with one another has changed dramatically in the last two decades. Today, much of our communication is via e-mail, text messaging, social media, and other online platforms. Do we see gender differences in electronic communication?

Let’s first consider texting. Research on texting has been mixed with regard to whether there are gender differences in the quantity of texts sent (e.g., Forgays et al., 2014; Tossell et al., 2012). When we look at the qualities of text messages, women tend to use more emoticons, but men tend to use a greater variety of emoticons (Tossell et al., 2012). This pattern may have more to do with gender roles than actual gender, though; another study found that femininity (on the Bem Sex Role Inventory, discussed in Chapter 3) was more strongly linked to emoticon usage than gender (Ogletree et al., 2014). Men are somewhat more permissive about the range of contexts in which they feel texting is appropriate, such as while sharing a meal with someone or being at church (Forgays et al., 2014). While there are gender similarities in the amount of sexually explicit text messages (i.e., “sexts”) sent, men report receiving more of such messages (Ogletree et al., 2014).

To explore gender differences and similarities in language use online, researchers may analyze language used in e-mail messages and posts to blogs and comment boards, for example.In one study, researchers examined the language used by men and women in postings to electronic bulletin boards as a function of whether the topic was gender stereotyped or gender neutral (Thomson, 2006). When topics were female stereotyped (e.g., fashion) or male stereotyped (e.g., sports), findings were similar to those found in face-to-face interactions. Women used more hedges and intensifiers, and they expressed more emotion and disclosed more personal information. Men, in contrast, issued more directives,disagreed more, and boasted more. These differences, however, were not found when the topic was gender-neutral.

Photo 5.3 Researchers have found evidence of gender differences and gender similarities in electronic communication.

©iStockphoto.com/m-imagephotography.

In another experiment by the same team, participants conducted e-mail correspondence with two fictitious netpals and received responses that, in actuality, came from the experimenter (Thomson et al., 2001). For each participant, one netpal responded with female-linked language (more emotion references, more intensifiers, etc.) and the other netpal responded with male-linked language (more opinions, fewer emotions, etc.). Interestingly, participants—whether male or female—responded differently depending on the gendered content coming from the netpal, shifting their e-talk to be like that of their netpal. This is a great illustration of how gender is constructed in social interactions and how gender patterns depend heavily on social context.

Gender stereotypes generally hold that women are more nonverbally expressive than men are (Briton & Hall, 1995). Are these stereotypes accurate? Here we will review the evidence on gender differences in nonverbal communication and what those differences mean (for meta-analyses, see Hall, 1998; McClure, 2000).

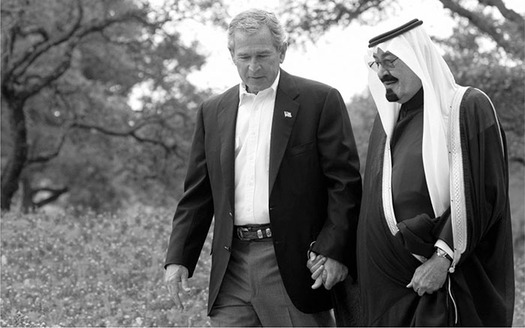

Photo 5.4 According to gender stereotypes in most Western cultures, two adult men hold hands only if they are romantically involved. By contrast, in some cultures, this nonverbal behavior merely conveys friendship. Images of President George W. Bush holding hands with Saudi Crown Prince Abdullah went viral when the two men met to discuss oil prices in 2005.

Jim Watson/AFP/Getty Images.

Encoding and Decoding Nonverbal Behavior

Effectively encoding (i.e., sending or conveying) and decoding (i.e., perceiving or reading) nonverbal behaviors are important for social interaction. Are men and women equally accurate in encoding and decoding nonverbal messages?

Meta-analysis tells us that women convey nonverbal messages or cues more accurately than men do (Hall, 1984). Is this because men are not very expressive in general or because their expressions are difficult to read? Some evidence indicates that men tend to suppress their nonverbal expressions, beginning around adolescence, whereas women tend to amplify their expressions (LaFrance & Vial, 2016). Women are also more accurate at decoding or reading others’ nonverbal cues. The gender difference in decoding exists even in childhood (McClure, 2000), though it is somewhat larger in adults (Hall, 1984; LaFrance & Vial, 2016).

These patterns of gender differences in encoding and decoding suggest that men and women differ not because they are inherently or innately different, but because they face pressure to adhere to different gender roles. In particular, the female role entails communality, or establishing and maintaining social relationships, which requires interpersonal sensitivity.

Smiling

Around the world, women smile more than men (LaFrance et al., 2003). According to meta-analyses, this gender difference fluctuates across the lifespan. In infancy and childhood, for example, it is nonexistent, d = –0.01 (Else-Quest et al., 2006), but in adolescence, the gender difference swells to d = –0.56 (LaFrance et al., 2003). The gap then declines, such that d = –0.30 in middle adulthood and d = –0.11 in older adulthood (LaFrance et al., 2003). In addition, some evidence suggests that gender differences seem to vary as a function of ethnicity; the pattern is more characteristic of White women than African American women (LaFrance et al., 2003).

Understanding the meaning of these gender differences in smiling requires thinking about why people smile. Sometimes, it indicates positive affect, such as happiness. Other times, its meaning is more complicated. Smiling has been called the female version of the “Uncle Tom shuffle”—that is, rather than indicating happiness or friendliness, it may serve as an appeasement gesture, communicating, in effect, “Please don’t hurt me or be mean.” A person who is smiling is not likely to be perceived as threatening.

Smiling may also be a status indicator: Dominant people smile less and subordinate people smile more, so women’s smiling might reflect their subordinate status (Henley, 1977, 1995). A number of studies, however, contradict this status interpretation. Although women consistently smile more than men in these studies, lower-status people (e.g., employees in a company) do not smile more than higher-status people (e.g., supervisors; Hall & Friedman, 1999; Hall et al., 2001).

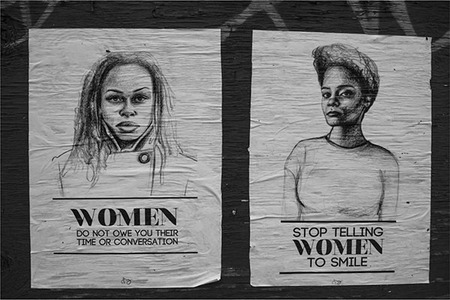

Photo 5.5 Artist Tatyana Fazlalizadeh’s work, Stop Telling Women to Smile (http://stoptellingwomentosmile.tumblr.com/)

Robert Stolarik/Polaris/Newscom

Smiling is also a part of the female role, which requires being warm, nurturant, and physically attractive. Most women can remember having their faces feel stiff and sore from smiling at a party or some other public gathering at which they were expected to smile. The smile, of course, reflected not happiness, but rather a belief that smiling was the appropriate thing to do. Women’s smiles, then, do not necessarily reflect positive feelings and may even be associated with negative feelings and pressure to adhere to the female role and “put on a happy face.”

Consistent with this view that smiling is part of the female role and therefore important in social situations, a meta-analysis found that the gender difference was more than twice as large when participants knew that they were being observed (d = –0.46) than when they did not know they were being observed (d = –0.19; LaFrance et al., 2003).

Most women can recall being told by men to smile, regardless of how they might be feeling. Popular media has even created an unfortunate term for women’s neutral (i.e., nonsmiling) facial expressions: resting bitch face. Indeed, when women violate the role requirement of smiling, others react negatively. For example, in one study, participants were given a written description of a person, accompanied by a photograph of a man or woman who was smiling or not smiling (Deutsch et al., 1987). The results indicated that the women who were not smiling were given more negative evaluations: They were rated as less happy and less relaxed in comparison with men and in comparison with women who were smiling.

Interpersonal Distance

In many countries, including the United States, it seems that men tend to prefer a greater distance between themselves and another person, whereas women tend to be comfortable with a smaller distance between themselves and others. This is particularly evident in same-gender pairs. For example, when two women interact, they tend to sit or stand closer to one another than two men do (e.g., Gifford, 1997). Similarly, people tend to prefer to maintain greater interpersonal distance from unfamiliar men than they do from unfamiliar women. Regardless of our own gender, we tend to need greater interpersonal space with men than with women in order to feel comfortable (e.g., Iachini et al., 2016).

What do we make of such differences? There are several possibilities. Our interpersonal space preferences may, at least in part, reflect concerns about falsely signaling that we are sexually or romantically interested in someone. It is a significant gender role violation for a heterosexual man to signal sexual interest in another man. Another possibility is that men are perceived as a threat or considered potentially dangerous, so we try to stay out of their “territory” to avoid conflict. By contrast, women are perceived as nonthreatening and considered safe, so we may feel less wary of getting in their space. Indeed, some have suggested that women have a small interpersonal distance as a result of, or in order to express, warmth, caring, or friendliness (Mast & Sczesny, 2010). Each of these possibilities is plausible; researchers who study interpersonal distance theorize that our interpersonal space preferences are shaped by sexual attraction, self-protective, and affiliative forces (Iachini et al., 2016). Also, each of these interpretations suggests that gender differences in interpersonal distance have more to do with gender roles than with gender. That is, how we position ourselves relative to other people is one way that we perform our gender roles.

One study compared the effects of gender, gender role identification, and sexual orientation on interpersonal distance (Uzzell & Horne, 2006). The researchers first administered the Bem Sex Role Inventory (see Chapter 3) to a sample of British college students who were diverse in terms of their sexual orientation (but not in terms of race/ethnicity; all were White). Then they assigned participants to interact with one another in a structured conversational task: Every 2 minutes, participants moved around to different stations or zones in the research lab. The researchers videotaped the interactions and marked the floor of the stations with a grid so that they could measure the distance between the feet of the conversational pairs. Results indicated significant effects of gender: Female-female pairs stood significantly closer to one another than did male-male or female-male pairs.

However, the effects of gender were completely eliminated when the researchers considered gender role identification. That is, self-reported femininity and masculinity were far more important than gender in determining interpersonal distance: Feminine people stood closer to their conversational partner, and masculine people stood farther away from their conversational partner. Sexual orientation had minimal effects on interpersonal distance. Although we don’t know if we can generalize these findings to other cultures or ethnic groups, it is clear that just examining differences between men and women is too simplistic. Gender roles are important!

Eye Contact

Eye contact between two people when speaking to each other can reflect patterns of power and dominance. Although the meaning of eye contact varies across cultures, in North American cultures higher-status people tend to look at the other person while they (the dominant people) are speaking. Lower-status people tend to look at the other person while listening. Researchers in this area compute a visual dominance ratio, defined as the ratio of the percentage of time looking while speaking relative to the percentage of time looking while listening (Dovidio et al., 1988; Mast & Sczesny, 2010).

Research on the connection between visual dominance and social power indicates, for example, that patterns of visual dominance are expressed across different levels of military rank and different levels of educational attainment (e.g., Dovidio et al., 1988). One study found that gender differences in visual dominance aligned with gender differences in knowledge about a gendered task, such as changing a tire versus changing a diaper (Brown et al., 1992). When researchers trained participants and eliminated gender differences in knowledge, the gender difference in visual dominance was also eliminated.

Another experiment investigated visual dominance as a function of both gender and power (Dovidio et al., 1988). College students were assigned to mixed-gender dyads. Each pair discussed three topics in sequence. The first discussion was on a neutral topic, and there was no manipulation of power (control condition). For the second topic, one member of the pair evaluated the other member and had the power to award extra-credit points to that person. For the third topic, the roles were reversed, and the person who had been evaluated became the evaluator.

In the control condition, men were visually dominant: Men looked at their partners more while speaking, and women looked more while listening. This was as predicted, given that men tend to have greater status or power relative to women. However, in the second and third discussions, when women were in the powerful role, they looked more than men while speaking, and men looked more while listening. That is, when women were given social power, they became visually dominant. These results again support a power or status interpretation of gender differences in eye contact and visual dominance. And as women gain more power in society, such patterns may well change.

Posture: Expansive or Contractive?

Another relevant aspect of nonverbal communication here is posture. People who are sitting or standing with their legs together and their arms close to their body are displaying a closed or contractive posture. By contrast, people who are sitting or standing with their limbs extended away from their body are displaying an open or expansive posture (see Photo 5.6). Expansive posture, sometimes referred to as power posing, takes up more space with one’s body and conveys social dominance and confidence, whereas contractive posture makes a person seem smaller and conveys submissiveness (LaFrance & Vial, 2016). In one study, participants were randomly assigned to conditions in which they were instructed to position their bodies in specific expansive or contractive poses (Carney et al., 2010). Relative to participants in the contractive pose condition, those in the expansive pose condition felt more powerful, were more willing to gamble their payment for participation, and even showed hormonal changes that are usually associated with power. The experimenters found these effects in male and female participants alike. Since then, over 30 experiments have replicated some of these effects (Carney et al., 2015), but they generally link expansive posture to feelings of power and dominance.

With all this discussion of power and dominance conveyed with nonverbal behaviors, it’s probably not surprising that we see gender differences in posture. Women are more likely than men to sit or stand in contractive poses (Hall, 1984). The gender difference in expansive posture is large, with men more likely than women to sit or stand in expansive poses (Hall, 1984). In one study, researchers observed passengers on the subway in Amsterdam and found that men more often displayed an expansive posture whereas women more often displayed a contractive posture (Vrugt & Luyerink, 2000). Indeed, some feminists have coined the term manspreading to refer to men’s expansive posture on public transit (Jane, 2016; see Photo 5.7).

Photo 5.6 What information do these people convey with their expansive and contractive postures?

©iStockphoto.com/drbimages.

Why do women tend to have more contractive posture? In some cases, it may be a strategy to avoid being perceived as threatening. In other cases, it may be a strategy to protect or shield one’s body from scrutiny and the male gaze (Kozak et al., 2014). So we might think of contractive posture as a protective strategy for women, which they’ve developed as an adaptation to objectification.

In summary, displaying expansive (vs. contractive) postures makes people feel more powerful and more willing to take risks, and men are more likely than women to display expansive postures.

How Women and Nonbinary People Are Treated in Language

Up to this point we have discussed gender differences and similarities in both verbal and nonverbal forms of communication. Another aspect of communication that needs to be considered is how gender issues are treated in our language. That is, how are women and people who do not fit within the gender binary treated in language? For example, trans and nonbinary people are often described with language that is inadequate, incomplete, or inaccurate, which can make them feel invisible and alienated (Langer, 2011). For genderqueer people, in particular, neither of the standard English language options he or she is an appropriate pronoun, but the alternative it is dehumanizing. Feminists have sensitized the public to the issue of sexist language, which includes inappropriate or irrelevant reference to gender, the use of masculine generics and male-as-normative/female-as-exception word choices, as well as the use of misgendering speech. Objectifying, sexualizing, or infantilizing euphemisms are also examples of sexist language. Here we will discuss patterns of sexist language and why they matter for the psychology of women and gender.

Photo 5.7 The Metropolitan Transportation Authority in New York City launched a campaign in 2015 to stop manspreading on subways and buses. http://web.mta.info/nyct/service/CourtesyCounts.htm#DUDESTOPTHESPREAD

© Copyright 2017 Metropolitan Transportation Authority.

Misgendering

One form of sexist language that can be particularly harmful is misgendering. Misgendering occurs when we use gendered language that is inconsistent with a person’s gender identity or when a person’s gender identity is misidentified by some other means. Misgendering occurs in a variety of circumstances and is particularly common among women working in stereotypically male professions, who may be referred to using masculine pronouns (e.g., Stout & Dasgupta, 2011). Transgender people are frequently misgendered (McLemore, 2014, 2016), such as when medical and mental health professionals label them by the gender they were assigned at birth rather than by their gender identity (Ansara & Hegarty, 2014; Hagen & Galupo, 2014). When people are misgendered, they may feel ignored, devalued, stigmatized, and hurt, or worse.

Using incorrect gendered pronouns to refer to transgender people has clearly harmful effects. When a person is misgendered in this way, their personal identity has not been affirmed, which threatens their sense of a strong and coherent identity (McLemore, 2014, 2016). Surveys of transgender men and women show that their experiences of being misgendered are linked to negative moods (such as anxiety and depression), feeling negatively about their identity and appearance, and feelings of stigmatization (McLemore, 2014, 2016).

Euphemisms

Generally, when there are many euphemisms for a word, it is a reflection of the fact that people find the word and what it stands for to be distasteful or stressful. For example, consider all the various terms we use in place of bathroom or toilet. And then note the great variety of terms that we substitute for die, such as pass away.

Feminist linguists have argued that we similarly have a strong tendency to use euphemisms for the word woman (Cralley & Ruscher, 2005; Lakoff, 1973). That is, people have a tendency to avoid using the word woman and instead substitute a variety of terms that seem more polite or less threatening, the most common euphemisms being lady and girl. Other euphemisms objectify or sexualize women, such as chick, shorty, honey, or ho. Another euphemism for woman is bitch, which has a hostile connotation.

How common are these different euphemisms? In one study, undergraduates were asked to list as many slang terms as they could for either woman or man (Grossman & Tucker, 1997). Fully 93% of men listed bitch as a term for woman! But then, so did 73% of the women. Overall, the euphemisms listed for woman were more likely to carry a sexual meaning than those listed for man; roughly 50% of the slang terms for woman were sexual, compared with 23% of the terms for man.

In contrast to the word man, which is used frequently and comfortably, woman is used less frequently and apparently causes some discomfort or we wouldn’t use euphemisms for it. However, the tendency to use euphemisms for woman can be changed by becoming sensitive to this tendency and by making efforts to use the word woman when it is appropriate.

Infantilizing

A 25-year-old man wrote to an advice columnist, depressed because he wanted to get married but had never had a date. Part of the columnist’s response was “Just scan the society pages and look at the people who are getting married every day. Are the men all handsome? Are the girls all beautiful?”

This is an illustration of the way in which people, rather than using woman as the parallel to man, substitute girl instead. As noted in the previous section, this in part reflects the use of a euphemism. But it is also true that boy refers to male children, and man to male adults. Somehow girl, which in a strict sense should refer only to female children, is used for female adults as well. Women are called by a term that seems to make them less mature and less powerful than they are; women are thus infantilized in language. Just as the term boy is offensive to Black activists, girl is offensive to feminists.

There are many other illustrations of this infantilizing theme. When a ship sinks, it’s “Women and children first,” putting women and children in the same category. Other examples in language are expressions for women, such as baby or babe. The problem with these terms is that they carry a meaning of immaturity and lack of power.

Male as Normative and Female as the Exception

One of the clearest patterns in the English language is the male as normative, or androcentrism, a concept discussed in Chapter 1 (Smith et al., 2010). The male is regarded as the normative (standard) member of the species, and this is expressed in many ways in language, for example, the use of man to refer to all human beings and the use of he for a neutral pronoun (as in the sentence “The infant typically begins to sit up around 6 months of age; he may begin crawling at about the same time”). The male-as-normative principle in language can lead to some absurd statements. For example, there is a state law that reads, “No person may require another person to perform, participate in, or undergo an abortion of pregnancy against his will” (Key, 1975).

At the very least, the male-as-normative usage introduces ambiguity into our language. When someone uses the word men, is the reference to male adults or to people in general? When Dr. Karl Menninger writes a book titled Man Against Himself, is it a book about people generally, or is it a book about the tensions experienced by male adults?

Masculine generics—that is, using masculine nouns and pronouns to refer to all people in a gender-neutral sense—have long been used in English. Some people excuse masculine generics and say they aren’t an example of male as normative speech. However, this explanation is problematic and inadequate. To illustrate the flaw in the “generic” logic, consider the objections raised by some men who joined the League of Women Voters. They complained that the name of the organization should be changed, for it no longer adequately describes its members, some of whom are now men. Suppose in response to their objection they were told that woman meant “generic person,” which of course could include a man. Do you think they would feel satisfied? Why are masculine generics acceptable but feminine generics aren’t?

For some time, feminist linguists have theorized that the masculine generic is an example of sexism in language (e.g., Lakoff, 1973; Stahlberg et al., 2007; Swim et al., 2004). And the use of masculine generics in English has been linked to the status of women in the United States. For example, Jean Twenge and her colleagues (2012) analyzed the ratio of male to female pronouns (e.g., he/she, his/hers, him/her) in the full texts of about 1.2 million U.S. books in the Google Books database. They found that when women’s status was higher, such as when women had greater educational attainment and labor force participation, the proportion of female pronouns was also higher. By contrast, when women’s status was lower, the use of female pronouns was less frequent.

The male-as-normative principle is also reflected in the female-as-the-exception phenomenon. This phenomenon occurs when a category that is considered normatively male has a female example; in those cases, gender is noted because it is a deviation from the norm. A newspaper reported the results of the Bowling Green State University women’s swimming team and men’s swimming team in two articles close to each other. The headline reporting the men’s results was “BG Swimmers Defeated.” The one for the women was “BG Women Swimmers Win.” As another example, in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, which destroyed much of New Orleans, federal officials referred to the governor of Louisiana, Kathleen Blanco, as the “female governor” (Lipton, 2005). At the same time, the governor of Mississippi, Haley Barbour, was never referred to as the “male governor.” His maleness would not have been considered newsworthy. We assume that athletes and governors are male, so in cases where they are female, this exception is often noted.

Many parallel words also reflect the male-as-normative, female-as-exception pattern. Some nouns can be qualified by adding a suffix—such as ess, euse, ette, or ix—that indicates female gender. For example, actor can be modified to actress, adulterer can be modified to adulteress, and comedian can be modified to comedienne. With such words, the masculine form is clearly the norm and the feminine form is a deviation from that norm.

Sometimes, noting a person’s gender in this way can be a strategy to increase visibility of an underrepresented gender group, but other times it’s just not relevant to the situation and may even stigmatize the person as the exception to the norm.

Gendering of Language

Languages vary with regard to how they handle gender. Some languages are gendered and others are genderless (Stahlberg et al., 2007). Languages such as English and Swedish are natural gender languages, which means that although personal pronouns are differentiated by gender (as in she, he, her, him, etc.), most personal nouns are gender neutral. So, for example, student is gender neutral, but you would use the subject pronoun she to refer to a female student.

By contrast, languages such as Spanish, German, Hindi, and Hebrew are grammatical gender languages, such that various parts of speech (including nouns, pronouns, verbs, adjectives, etc.) that would not naturally be considered masculine or feminine are inflected with gender. For example, in German the word for the noun student is masculine, as in der Student, but the word for the noun university is feminine, as in die Universität. Young children whose first language is a grammatical gender language, such as Spanish, quickly learn this information as they learn to speak correctly (Lew-Williams & Fernald, 2007).

Languages such as Finnish, Mandarin, and Turkish are genderless languages, in that neither personal nouns nor pronouns are differentiated for gender. For example, in Turkish the word for the noun student is öğrenci, which is gender neutral, and you would use the subject pronoun o for that student, regardless of their gender.

Researchers have demonstrated that these different language types reflect societal gender equality. In a study of 111 countries with different language types, researchers found that a country’s level of gender equality (as described in Chapter 1) was associated with its language type (Prewitt-Freilino et al., 2012). Countries with grammatical gender languages tend to have less gender equality relative to countries with natural gender languages or genderless languages. In addition, masculine generics are more prominent in grammatical and natural gender languages (Vainapel et al., 2015).

Does Sexist Language Actually Matter?

You might be asking yourself: Does any of this stuff—such as the use of masculine generics and gendered languages—actually matter? It’s good to be skeptical, but it’s better to examine the data and weigh the evidence.

Sexist language and sexist attitudes go hand in hand. The use of masculine generics reflects not only the cultural or societal status of women (Twenge et al., 2012), but also personal attitudes about gender. For example, Janet Swim and her colleagues (2004) conducted two studies on sexist beliefs and the use of sexist language. In the first study, participants completed measures of sexist beliefs and were asked to mark a list of sentences for grammatical and sexist language errors. Swim et al. found that participants who endorsed modern sexist beliefs (discussed in Chapter 1) were less able to detect sexist language, in part because they had narrower definitions of sexist language. In the second study, participants completed measures of sexist beliefs and wrote responses to how they would respond to several moral dilemmas. Swim et al. then coded participants’ responses for the use of sexist language, such as masculine generics. Participants who held modern sexist beliefs used sexist language more often.

Some research finds gender differences in attitudes toward sexist language: Men are generally more supportive of sexist language, and women are more supportive of nonsexist language (e.g., Douglas & Sutton, 2014; Parks & Roberton, 2004). Karen Douglas and Robbie Sutton (2014) conducted a study to explore why this gender difference exists. Participants completed a questionnaire measuring their general preference for social hierarchy and inequality over equality (known as social dominance orientation; Sidanius & Pratto, 1999) and their tendency to think gender inequality is fair and legitimate (or system-justifying beliefs). Douglas and Sutton found that gender differences in attitudes toward sexist language were explained by social dominance orientation and system-justifying beliefs. In other words, the finding that men are more supportive of sexist language was explained by men’s preference for social inequality and belief that gender inequality is fair. These findings are in line with the argument that sexist language is caused by sexist beliefs, but, because the data are quasi-experimental, we can’t actually infer causation.

Some argue that sexist language is a symptom of sexist attitudes and societal gender inequality. The generic use of man and he reflects the fact that we think of the male as the norm for the human species and that we carry gender stereotypes and biases in our thoughts (Cralley & Ruscher, 2005; Stahlberg et al., 2007). That is, we use sexist language because we think in sexist terms. The practical conclusion from this is that if we change our thought processes, language will change with them.

An alternative perspective comes from one of the classic theories of psycholinguistics, the Whorfian hypothesis (Whorf, 1956). The Whorfian hypothesis states that the specific language we learn influences our mental processes. If that is true, then gendered language doesn’t just reflect gender inequality; gendered language perpetuates gender inequality. Similarly, some experts have argued that language encodes inequalities in a culture and that language can normalize bias by making it part of everyday speech (Ng, 2007).

In one study, researchers examined how using a natural gender language or a grammatical gender language influenced people’s self-reported sexist attitudes (Wasserman & Weseley, 2009). Participants who were native English speakers and bilingual were randomly assigned to respond to the survey in either a natural gender language (English) or a grammatical gender language (Spanish or French). Participants who completed the survey in a grammatical gender language reported more sexist attitudes than participants who completed the survey in the natural gender language. These findings suggest that using a grammatical gender language may actually promote sexist attitudes. Yet feminists need not despair—another study found that, even in a grammatical gender language such as German, nonsexist language can still be used (Koeser et al., 2015).

In another study, researchers randomly assigned research participants in Israel to complete a survey measuring aspects of academic motivation in Hebrew (a grammatical gender language) using either masculine generics or a gender-neutral form (i.e., using both masculine and feminine forms; Vainapel et al., 2015). They found gender differences in self-efficacy when the survey used masculine generics but gender similarities when gender-neutral forms were used. That is, women’s self-efficacy scores were lower than men’s scores only when masculine generics were used.

In addition, the Whorfian hypothesis would predict that practices like the use of masculine generics actually make us think that the male is normative and the female is the exception. The process by which language encodes inequality and influences how we think about gender might start with very young children when they are just beginning to learn their first language. As we develop, then, cultural linguistic practices become deeply ingrained and form the foundation for how we think about gender.

In fact, many studies show that the use of masculine generics shapes how we think (e.g., Braun et al., 2005; Foertsch & Gernsbacher, 1997; Gastil, 1990; Hamilton, 1988; Moulton et al., 1978; Vervecken & Hannover, 2015). We highlight a few of these studies here.

One of us (JSH) conducted a series of studies to investigate the effects of sexist language on children (Hyde, 1984a). First, she generated an age-appropriate stimulus sentence and asked first-, third-, and fifth-grade children to tell stories in response to it. The children were divided into three groups. The stimulus sentence was as follows:

When a kid goes to school, ___ often feels excited on the first day.

One-third of the children received he for the blank, one-third received they, and one-third received he or she. When the pronoun was he, only 12% of the stories were about women, versus 42% when the pronoun was “he or she.” Interestingly, when the pronoun was he, not a single elementary school boy told a story about a girl. Clearly, then, when children hear he in a gender-neutral context, they think of a boy or man. Hyde also asked the children some questions to see if they understood the grammatical rule that he in certain contexts refers to everyone, both men and women. Few understood the rule; for example, only 28% of the first graders gave answers showing that they knew the rule.

Hyde also had the children fill in the blanks in some sentences, for example:

If a kid likes candy, ___ might eat too much.

The children overwhelmingly supplied he for the blank; even 72% of the first graders did so.

This research shows two things. First, the majority of elementary school children have learned to supply he in gender-neutral contexts (as evidenced by the fill-in task). Second, the majority of elementary school children do not know the rule that he in gender-neutral contexts refers to both men and women and have a strong tendency to think of men in creating stories from neutral he cues. For them, then, the chain of concepts is as follows: (1) The typical person is a “he.” (2) He refers only to boys and men. Logically, then, might they not conclude that (3) the typical person is male? Language seems to contribute to androcentric thinking in children.

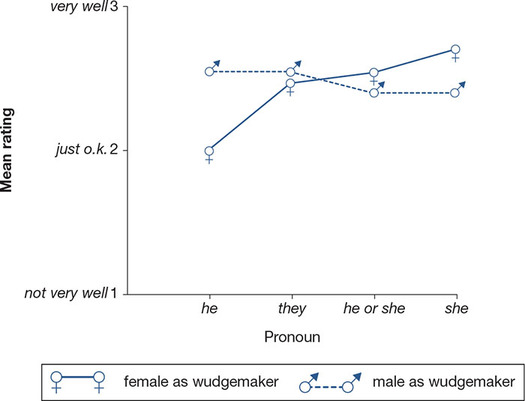

In a final task, Hyde created a fictitious, gender-neutral occupation: wudgemaker.

Few people have heard of a job in factories, being a wudgemaker. Wudges are made of plastic, are oddly shaped, and are an important part of video games. The wudgemaker works from a plan or pattern posted at eye level as ___ puts together the pieces at a table while ___ is sitting down. Eleven plastic pieces must be snapped together. Some of the pieces are tiny, so ___ must have good coordination in ___ fingers. Once all eleven pieces are put together, ___ must test out the wudge to make sure that all of the moving pieces move properly. The wudgemaker is well paid and must be a high school graduate, but ___ does not have to have gone to college to get the job.

One-quarter of the children received he in all the blanks, one-quarter received they, one-quarter received he or she, and one-quarter received she. The children then rated how well a woman could do the job on a 3-point scale: 3 for very well, 2 for just okay, and 1 for not very well. Next, they rated how well a man could do the job, giving ratings on the same scale. The results are shown in Figure 5.1. Which pronoun the children were given didn’t seem to affect their ratings of men as wudgemakers, but the pronoun had a big effect on how women were rated as wudgemakers. Notice in the graph that when the pronoun he was used, women were rated at the middle of the scale, or just okay. The ratings of women rose for the pronouns they and he or she, and finally were close to the top of the scale when children heard the wudgemaker described as she. These results, then, demonstrate that pronoun choice does have an effect on the concepts children form; in particular, children who heard he in the job description thought that women were significantly less competent at the job than children who heard other pronouns did.

Other experiments show that when job titles are marked for gender (e.g., policeman), children are more likely to view those occupations as being appropriate for only one gender, relative to when job titles are unmarked for gender (e.g., plumber; Liben et al., 2002). There is also reason for concern about the effect on broader issues, such as girls’ self-efficacy in male-stereotyped jobs (Vervecken & Hannover, 2015). Research demonstrates that men and boys remember material better when it is written with masculine generics, but girls and women remember it better when it is written with gender-neutral or feminine generics (Conkright et al., 2000).

Figure 5.1 Children’s ratings of the competence of women and men as wudgemakers, as a function of the pronoun they heard repeatedly in the description of the wudgemaker.

Source: Hyde (1984a). Copyright © 1984 by the American Psychological Association.

In answer to the original question of whether this language business is really important, the data show that it is. We need to be concerned about the effects that sexist pronoun usage has on children as their attitudes about gender and aspirations for themselves are developing. Of course, social learning theory would tell us that, if we want children to use nonsexist language, we adults should model it for them!

Some people believe that in theory it would be a good idea to eliminate sexism from language, but in practice they find themselves having difficulty doing this in their speaking or writing. Next we discuss some practical suggestions for avoiding sexist language (American Psychological Association, 2010; Miller & Swift, 1995) and for dealing with some other relevant situations.

Toward Nonsexist Language

Our review of the evidence indicates that sexist language reflects societal gender inequality and has harmful effects on how we think. Not surprisingly, feminists advocate for nonsexist language in order to reduce sexist stereotyping and discrimination (e.g., Sczesny et al., 2016; Stahlberg et al., 2007). Nonsexist language might include omitting inappropriate or irrelevant references to gender, replacing masculine forms of words (e.g., nouns such as policeman, pronouns such as he) with gender-unmarked forms (e.g., police officer, they), and increasing the use of feminine forms (e.g., using he or she instead of only he) to make female referents more visible.

A common solution is to use he or she instead of the generic he, him or her instead of him, and so on. Therefore, the generic masculine in sentence 1 is modified as in sentence 2:

- When a doctor prescribes birth control pills, he should first inquire whether the patient has a history of blood clotting problems.

- When a doctor prescribes birth control pills, he or she should first inquire whether the patient has a history of blood clotting problems.

Some believe that the order should be varied so that he or she and she or he appear with equal frequency. If he or she is the only form that is used, women still end up second!

In addition, the problem with using a phrase such as he or she is that, while it makes women more visible, it also reaffirms the gender binary and, therefore, makes nonbinary people invisible. So another possibility is to switch from the singular to the plural, because plural pronouns do not signify gender, at least in English. Therefore, the generic masculine in sentence 1 can be modified as follows:

- When doctors prescribe birth control pills, they should first inquire whether the patient has a history of blood clotting problems.

Another possibility is to reword the sentence so that there is no necessity for a pronoun, as in this example:

- A doctor prescribing birth control pills should first inquire whether the patient has a history of blood clotting problems.

Another solution to this problem in English is the singular use of they and their. Singular they was standard usage in English until the late 1700s, when a group of grammarians decided it was wrong (Bodine, 1975). Today, there is increasing acceptance of the use of singular they in written English, and its use has long been widespread in spoken English. Singular they is especially useful when someone’s gender is not known or identified.

As consciousness of sexist language and critiques of the gender binary have become more visible, new gender-neutral pronouns have been created. For example, one set that has been proposed is tey for he or she, tem for him or her, and ter for his or her. Thus one might say, “The scientist pursues ter work; tey reads avidly and strives to overcome obstacles that beset tem.” Entire books have been written with this usage. These new pronouns have a great deal of merit, but they are not widely used yet. If the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Wall Street Journal, and the president all started using ter, tey, and tem, these terms would certainly have a better chance of widespread use.

Making a conscious effort to avoid misgendering people is also important for using more inclusive and nonsexist language. When in doubt of the correct pronouns to use for a person, sometimes the best solution is to politely ask that person. Still, if you make a mistake and misgender someone, a simple apology and correction will do.

Space does not permit a complete discussion of all possible practical challenges that may arise in trying to avoid sexist language and be more inclusive with our word choices. Usually, however, a little thought and imagination can solve most problems. For example, the salutation in a letter, “Dear Sir,” can easily be changed to “Dear Colleague” or simply “To Whom It May Concern.” Salutations such as “Dear Madam or Sir” and “Dear Sir or Madam” reaffirm the gender binary and are therefore best avoided.

Another aspect of nonsexist language is to avoid irrelevant reference to a person’s gender and gender identity. When a person’s gender isn’t relevant, it’s best not to identify it (Dumond, 2014). Likewise, if a person’s transgender or cisgender status isn’t relevant, it shouldn’t be identified (National Lesbian & Gay Journalists Association, 2016).

Honorific titles such as Mr., Miss, Mrs., and Ms. can be problematic for several reasons. First, these titles necessarily identify gender even when gender may not be relevant. In turn, using these titles carries the risk of misgendering people. In addition, looking just at Miss and Mrs., these terms are considered by many to be outdated and condescending to women. How often is it necessary to identify a woman’s marital status in her title? Moreover, Miss is often used in an infantilizing manner. Ms. addresses both of these concerns and affords the same status to a woman as to a man, regardless of marital status. But is there a title that is more inclusive of nonbinary people, a title that avoids misgendering? In fact, more people have begun to adopt the use of the gender-neutral title Mx. (pronounced mix; Corbett, 2015). Like Ms., this title isn’t an abbreviation of an existing word in English. Its use isn’t yet widespread, but neither was Ms. until quite recently!

Institutional Change

A number of institutions have committed themselves to using and encouraging nonsexist language. For example, most textbook publishers have guidelines for nonsexist language and refuse to publish books that include sexism. (Two examples are Scott, Foresman and McGraw-Hill, which initiated this policy in 1972 and 1974, respectively.) The American Psychological Association (2010) requires the use of nonsexist language in articles in the journals it publishes. And Webster’s Dictionary has a policy of avoiding masculine generics and other forms of sexist language (“No Sexism Please,” 1991). In general, these are good sources for the reader wanting more detail on how to reduce sexist language.

Nonetheless, some forms of sexism—particularly cisgenderism, which privileges cisgender people—have not yet been adequately addressed by most institutions. For example, although the American Psychological Association’s (2010) Publication Manual instructs authors to avoid masculine generics when referring to groups of people, it also instructs authors to “be clear about whether you mean one sex or both sexes” (p. 73). The problem with such statements is that it reaffirms the gender binary and makes transgender, intersex, and nonbinary people invisible.

The use of gender-neutral pronouns is increasing at public and private universities in the United States, some of which now offer incoming students the option to register their gender pronouns. For example, in the fall of 2015, Harvard University gave new students the following options: he, she, they, e, and ze. Notice that three of these pronouns—they, e, and ze—are gender-neutral!

In Sweden, a new gender-neutral pronoun (hen) has been incorporated into the official Swedish language and is used in Swedish media and government settings. Recall that Swedish is a natural gender language, like English.

Many occupational titles, particularly in government agencies, have also changed. It is worth noting that some of the changes introduce definite improvements. For example, firemen has been changed to firefighters. In addition to being nonsexist, the newer term makes more sense, because what the people do is fight fires, not start them, as one might infer from the older term.

Language and Careers

Our discussion of gender and language raises important practical questions for gender and the workplace. Though we discuss gender and work in detail in Chapter 9, there are two issues regarding language that are relevant in this chapter.

One issue is how the use of sexist language in job descriptions may contribute to a lack of gender diversity in the workplace. For example, the use of sexist language in a job ad might signal that only men should apply. A series of experiments explored the psychological effects of using sexist language during a mock job interview (Stout & Dasgupta, 2011). Under the guise of a career development program, researchers invited undergraduate participants to the lab to do mock job interviews. In the first part of the interview, participants read a job description that used sexist language (e.g., masculine generics such as he, him, guys), “gender-inclusive” language (e.g., he or she), or gender-neutral language (e.g., one, the employee). Both male and female participants reported the job description in the sexist language condition to be sexist. Among women only, the type of language used affected their feelings about the job. Women in the sexist language condition expected lower sense of belonging in the job, reported lower motivation to get the job, and identified less with the job, relative to the other two language conditions. In a follow-up study with only female participants, the researchers also observed the participants’ nonverbal behavior and found that, in the sexist language condition, women displayed less interested and more negative nonverbal behaviors. If an employer wants a diverse workforce, they shouldn’t use sexist language!

For women aspiring to careers in male-dominated occupations, consider the implications of gender differences in verbal communication. Which styles of speaking will work best for such women? One interesting experiment assessed the impact of women using stereotyped patterns of tentative speech compared with assertive speech (Carli, 1990). Participants listened to an audiotape of a persuasive speech delivered by either a woman or a man. On one of the tapes, the woman used many tag questions (“Great day, isn’t it?”), hedges (“sort of”), and disclaimers (“I’m no expert, but . . .”), indicating tentativeness. On another tape, she used no tag questions, hedges, or disclaimers, thus indicating assertiveness. In the third tape, a man used tentative speech, and in a fourth tape, a man used assertive speech. The results indicated that the female speaker who used tentative speech was more influential to men than the assertive female speaker. For female listeners, the effect was just the reverse: They were more influenced by the woman using assertive speech than by the woman with tentative speech. Interestingly, men were equally influential whether their speech was tentative or assertive. Apparently, men acquire their status and influence simply by being male; speech style makes little difference. But to return to the implications for women and careers, the results of this study indicate that changing from tentative to forceful speech for women is likely to have different effects, depending on whether the woman is speaking to a man or a woman. Tentative speech seems to work best with men, and assertive speech works best with women. Other research shows that some people react negatively to gender-norm violations in women’s speech (Lindsey & Zakahi, 2005). Women have to strike a delicate balance as they try to advance their careers without evoking the ire of gender traditionalists.

In Conclusion

In this chapter, we began by considering the evidence on gender differences in verbal and nonverbal communication.We think it is important to remember that verbal and nonverbal communication, like many other forms of human behavior, are regulated by cultural norms and gender stereotypes. Violations of gender stereotypes are sometimes perceived as evidence that a person is queer. Indeed, people often rely on both verbal and nonverbal behaviors for cues regarding a person’s sexual orientation (e.g., Ambady et al., 1999; Van Borsel & Van de Putte, 2014). Although many people believe that they can rely on particular gestures, styles of speech, and other nonverbal behaviors as cues to sexual orientation—often referred to as gaydar—evidence indicates that gaydar is inaccurate (Cox et al., 2016). In other words, it is often difficult to interpret violations of gender stereotypes of verbal and nonverbal behavior.

Gendered patterns of verbal and nonverbal behaviors—whether tentativeness in speech or interpersonal distance—always develop in cultural contexts. As such, we should be mindful of the intersectionality of gender and culture when interpreting gender differences and similarities.

Experience the Research: Gender and Conversational Styles

Recruit four students, two who identify as men and two who identify as women (and who are not in this class), to participate. Pair one man and one woman together alone in a room and tell them that you are going to give them a topic to discuss and that you want to record their discussion to analyze it for a class. Be sure to obtain their permission to record the conversation, and assure them that you will not reveal to anyone the identities of your participants. Then give the pair a controversial topic to discuss—perhaps a current controversy on your campus or in national politics. Be sure that the topic is not gender stereotyped so that one person will feel superior to the other. For example, “How good is the new quarterback on the football team?” would probably not be a good topic. By contrast, “Would you vote for the new health care bill before Congress and why?” is a good topic. Tell them that you will record their discussion for about 10 minutes. You should remain in the room and note any observations you have of their discussion. Specifically, count the number of times each person nods in response to what the other is saying.

Repeat this procedure with the second male-female pair. You now have two audio recordings for data. Analyze the recordings in the following ways:

- Count the number of times the man interrupted the woman and the woman interrupted the man. Did men interrupt women more than the reverse?

- Count the number of tag questions (see text for explanation). Did women use more tag questions than men did? Having listened to their conversation, how would you interpret the difference you found? Were the women indicating uncertainty, or were they trying to encourage communication and maintain the relationship?

- Count the number of hedges (e.g., “sort of”). Did women use more hedges than men?

- Did women nod more in response to what men were saying or the reverse?

Chapter Summary

Tannen’s different cultures hypothesis holds that gender differences in speech patterns stem from the different goals that men and women have when they communicate, such that women use more affiliative speech, whereas men use more assertive speech; meta-analyses provide limited support for this position, as the gender differences found are very small. Mulac proposed that the verbal communication of girls and women tends to be rated as more socially intelligent and aesthetically pleasing, whereas the verbal communication of boys and men is rated as more dynamic and aggressive. While data show these differences to be subtle, this research may be used to inform communication therapy for transgender women and men.

Many gender differences in nonverbal communication—including encoding and decoding communication, smiling, visual dominance, interpersonal distance, and posture—are tied to gender roles and power.

Analyses of the way women are treated in language reveal patterns in which the male is normative, as in the use of masculine generics. Research with adults as well as children shows that masculine generics are not psychologically gender neutral, but rather evoke images of men. In addition, such sexist language appears to both reflect and perpetuate gender inequalities. Sexist language may contribute to the early social construction of gender for children.

Nonsexist language involves omitting inappropriate or irrelevant references to gender, using gender-unmarked forms, and avoiding misgendering language. While many efforts to reduce sexist language have become standard, some forms of sexism, such as cisgenderism, persist.