Chapter 9 Gender and Work

Outline

- 1. Pay Equity and the Wage Gap

- Focus 9.1: Psychology and Public Policy: Employment Discrimination in the United States

- 2. Gender Discrimination and Workplace Climate

- 3. Leadership and the Glass Ceiling

- 4. Work and Family Issues

- Focus 9.2: Psychology and Public Policy: Family Leave

- Experience the Research: Entitlement

- 5. Chapter Summary

- 6. Suggestions for Further Reading

The majority of American women hold paying jobs. Among women between the ages of 25 and 54, 71% of White women and 69% of Black women hold jobs (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2010). The working woman, then, is not a deviation from the norm; she is the norm. Women today constitute 47% of the American labor force—very close to half—compared with 29% in 1948 (White House Council of Economic Advisers, 2016).

Pay Equity and the Wage Gap

In 1960, American women earned about 61 cents for every dollar American men earned (U.S. Census Bureau, 2016d). While that gap has decreased in the decades since, we have not yet achieved pay equity: today, women earn about 80 cents for every dollar men earn (U.S. Census Bureau, 2016d). This gender gap in wages is larger in the United States than it is in many developed nations, including Norway, Hungary, Italy, and New Zealand (White House Council of Economic Advisers, 2016). And this gap gets larger over the course of women’s careers. The wage gap occurs despite the fact that, on average, women are actually better educated compared with men.

An intersectional perspective demonstrates that the gender gap in wages is also linked to ethnicity. Table 9.1 shows median annual earnings as a function of both gender and ethnicity as well as the gender gap in wages within each ethnic group. These statistics clearly demonstrate that, within every ethnic group, women earn less than men. Yet the size of the wage gap varies across ethnic groups: It is largest among White Americans, and smallest among African Americans. Note, also, the highest paid group—Asian American men—earns nearly twice as much as the lowest paid group—Hispanic/Latina women. In sum, pay inequity exists in each group, but it’s most severe among Hispanic Americans.

Wages also vary at the intersection of age and gender, such that the wage gap is smallest among younger adults and largest among older adults (Joint Economic Committee Democratic Staff, 2016). What appears to happen is that, over time, small or minor discrepancies in wages accumulate, such that they are negligible among younger adults but grow over decades of work. The wage gap is significant beginning at about age 35. This wage gap is a serious concern for older adults, who are often on fixed retirement and social security income (which are determined largely by how much they earned in previous years). Older women are more likely than older men to live in poverty.

The Motherhood Penalty

What is behind the wage gap? One factor that seems to contribute to the wage gap is women’s family roles and responsibilities. Although heterosexual marriage and children raise the amount of household work for both women and men, the effect is much greater for women (a point we will return to in the section on work and family issues). In particular, there is a motherhood penalty in wages, such that women’s lifetime earnings are reduced by having children, typically by about 5% to 10% for each child (Budig & Hodges, 2010; J. R. Kahn et al., 2014). By contrast, fatherhood generally does not carry such a wage penalty; indeed, there is evidence of a fatherhood bonus (e.g., Budig, 2014; Evers & Sieverding, 2014)!

The reduction in women’s earnings is partly due to behaviors such as taking time off from work after the birth of a child, cutting their education short, working jobs with more flexible hours, and working fewer hours because of caregiving responsibilities. These are all things that women are more likely than men to do.

Source: Data from U.S. Census Bureau (2016c). Table created by Nicole Else-Quest.

The wage gap is women’s earnings as a percentage of men’s earnings.

For example, to be a successful partner in a law firm or to earn tenure as a college professor requires considerably more than 40 hours of work per week—often 60 to 80 hours. Some (though certainly not all) women in this situation may choose not to commit to the extra hours, because they want to spend them with their family or because family commitments simply prevent working beyond 40 hours per week. These women then work in the less well-paid and less prestigious levels of their occupations—lawyer but not partner, lecturer but not tenured professor. There is much questioning of why women’s family responsibilities should interfere with their job advancement when men’s do not.

Photo 9.1 A motherhood penalty for her and a fatherhood bonus for him? Family roles and responsibilities, as well as child care and family leave policies, contribute to the wage gap.

©iStockphoto.com/monkeybusinessimages.

The motherhood penalty is greatest for women who have three or more children and for women who have their children at younger ages (Kahn et al., 2014). An intersectional analysis suggests that women in low-wage work may also experience a more severe motherhood penalty (Budig & Hodges, 2010).

What can be done to reduce the motherhood penalty? Cross-national research suggests that affordable child care is crucial. A study of women in 13 European countries found that the motherhood penalty in wages was reduced in countries with publicly funded child care (Abendroth et al., 2014). The researchers concluded that, when women have improved access to child care, there is less of a need for them to leave their jobs or work fewer hours in order to take care of their children.

Of course, the motherhood penalty in wages may also stem from discrimination in the workplace. Employers might discriminate against mothers, something that is illegal but difficult to prove. We will return to the topic later in this chapter.

Occupational Segregation

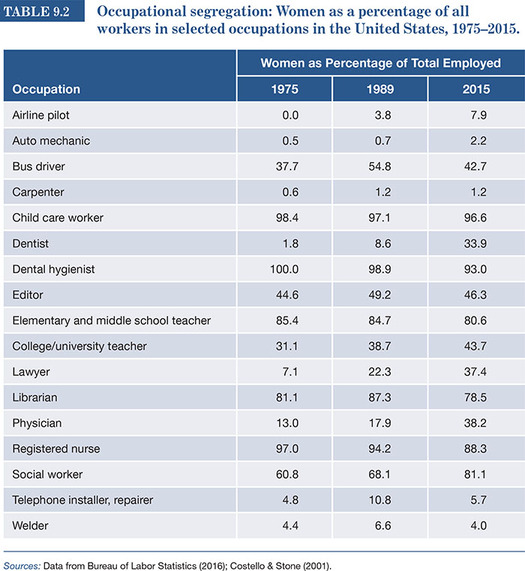

Another clear factor contributing to the wage gap is occupational segregation. Most occupations are segregated by gender. Very few jobs are held by equal proportions of men and women. Table 9.2 lists women’s share of a variety of occupations in the United States and how that share has changed in recent decades. Notice that most occupations are highly segregated by gender, with 90% or more of the workers coming from one gender. Men dominate as airline pilots, auto mechanics, carpenters, and welders. Women dominate as child care workers, dental hygienists, and registered nurses. Only a few occupations come close to a 50-50 gender ratio: bus drivers, editors and reporters, and college and university teachers.

Beyond the problem of the wage gap, occupational segregation remains a critical issue for other reasons. The stereotyping of occupations severely limits people’s thinking about work options. A man might think himself well suited to being a registered nurse or a woman might love carpentry, but they are discouraged from following their passions because certain occupations are not considered appropriate for them because of their gender (see Chapter 8).

Occupations are segregated by race/ethnicity as well, and this segregation has numerous consequences. For example, in one study Black children 6 to 7 years of age were told about fictitious occupations, and people with those jobs were shown as either only Black, only White, or some from each (Bigler et al., 2003). The children then rated the status of the occupations. Jobs that had been shown as being done only by White people were rated as higher in status than jobs shown as being done only by Black people, with ratings for mixed-race jobs rated in between. This experiment provides powerful evidence that Black children have learned that Black adults generally hold lower-status occupations, and they generalize this principle even to fictitious occupations.

Economists estimate that about 51% of the wage gap is due to occupational segregation (White House Council of Economic Advisers, 2016). Occupations that are predominantly held by women are almost invariably low paying.

Yet even when men and women work side by side in similar jobs, the wage gap persists (White House Council of Economic Advisers, 2016). For example, about equal numbers of men and women work as financial managers, but women in those jobs make only 65 cents for every dollar men make (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2016). So occupational segregation is only one part of the puzzle.

It was the recognition of the gender gap in wages, and the fact that it was partly due to occupational segregation, that led to the concept of comparable worth. Comparable worth is the principle that people should be paid equally for work in comparable jobs—that is, jobs with equivalent responsibility, educational requirements, level in the organization, and required experience. As an illustration of the importance of comparable worth, in one state both liquor store clerks and librarians are employed by the state government. Liquor store clerks are almost all men, and the job requires only a high school education. Librarians are almost all women, and the job requires a college education. But in this state, liquor store clerks are paid more than librarians. The principle of comparable worth argues against this pattern. It says that librarians should be paid at least as much as, and probably more than, liquor store clerks because librarians must be college graduates. Several states have enacted comparable worth legislation, stating that at least all government employees must be paid on a comparable worth basis. This requires extensive job analyses by industrial/organizational psychologists to figure out which jobs have equivalent requirements in terms of responsibilities, education, and so on, regardless of gender. Preliminary results in states that have legislated this principle are promising, and it turns out not to be terribly expensive for employers to pay on a comparable worth basis. Federal laws have also been passed to ensure equal pay for equal work (see Focus 9.1).

Compensation Negotiation

Another cause of the wage gap that has been proposed has to do with wage negotiation; that is, maybe women are paid less because they don’t negotiate for higher pay as well as men do. This proposal may strike you as yet another female deficit explanation that blames women for being paid less than men, but let’s consider the evidence.

A recent meta-analysis examined gender differences in economic negotiation outcomes, analyzing data from studies that measured how successful people were at negotiating different economic outcomes, including salary (Mazei et al., 2015). Participants included undergraduate and graduate students as well as businesspeople. The overall effect size was d = 0.20, a small gender difference, indicating that men achieved somewhat better economic outcomes than women in negotiation situations. As is often the case, however, the size of the gender difference depended on context. Moderator analyses showed that gender differences were reduced when negotiators had experience with negotiation or when the negotiators were given information about the bargaining range (for example, information about the aspects of the situation that were negotiable). In other words, the more negotiators knew about negotiation generally and about the situation specifically, the smaller the gender difference in outcomes.

Focus 9.1 Psychology and Public Policy: Employment Discrimination in the United States

Several important pieces of federal legislation prohibit employment discrimination in actions such as unfair hiring, promotions, wages, termination, and layoffs. Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibits employment discrimination based on “race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.” Title VII also called for the creation of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), which has the authority to investigate and, when appropriate, file lawsuits against employers for violations of these and subsequent prohibitions against employment discrimination, including discrimination on the basis of disability, genetic information, and age (i.e., being 40 or older).

What is particularly relevant for the psychology of women and gender is the meaning of sex in Title VII. Initially, sex referred primarily to the status of being female (or male) and included protections for women during pregnancy and childbirth. Since then, the EEOC has clarified that sex includes pregnancy, gender identity, and sexual orientation. Thus, Title VII affirms that, for example, a qualified job applicant cannot be denied a job because they are pregnant, a transgender woman cannot be denied access to the women’s restroom at work, and a lesbian woman cannot be denied a promotion for not conforming to the employer’s gendered expectations or stereotypes. Although the EEOC defines sex in this way, legal precedent has not yet been set in the federal courts. In other words, federal protections against discrimination on the basis of gender identity (rather than gender assigned at birth) and sexual orientation exist only in theory, not in practice. Thus, it is uncertain the extent to which trans and nonbinary people are legally protected from employment discrimination under Title VII. Some states provide protections, but in most it is perfectly legal to fire someone for being trans, queer, or gender nonconforming.

Photo 9.3 President Barack Obama signed the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act of 2009 into law. The law states that the 180-day statute of limitations for employees to sue for wage discrimination resets at each paycheck.

Retrieved from the White House Archives.

Other legislation has focused specifically on the issue of pay equity between women and men. For example, the 1963 Equal Pay Act requires that people be paid the same wages for the same job, regardless of their gender. Yet it falls short of the standards set by the principle of comparable worth because it requires that, for gender-equal pay, the jobs must be identical, not merelycomparable.

More recently, the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act of 2009 made it easier for targets of wage discrimination to sue their employers for violating Title VII, in that it clarified that the 180-day statute of limitations for employees to sue for wage discrimination resets at each paycheck. The law was named after Lilly Ledbetter, who filed a pay discrimination claim with the EEOC and sued her employer, Goodyear Tire Company, for being paid less than her male counterparts. Ledbetter worked as a manager at Goodyear for 19 years and filed her lawsuit 6 months before her retirement in 1998. Initially, her pay was similar to that of men in her position, but over time a substantial wage gap developed, which also negatively affected her social security and eventual retirement income. Her claim was ultimately denied in 2007 by the U.S. Supreme Court in Ledbetter v. Goodyear Tire and Rubber Co. solely on the grounds that more than 180 days had passed since the discrimination started. In other words, before this law was passed, a person might be discriminated against for many years but have no grounds for legal action because the statute of limitations had run out 180 days after the first unfair paycheck. This statute of limitations is unrealistic in most cases. In the dissenting opinion, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg acknowledged that it is often difficult for employees to identify when pay discrimination has occurred:

Pay disparities often occur, as they did in Ledbetter’s case, in small increments; cause to suspect that discrimination is at work develops only over time. . . . It is only when the disparity becomes apparent and sizable, e.g., through future raises calculated as a percentage of current salaries, that an employee in Ledbetter’s situation is likely to comprehend her plight and, therefore, to complain. (pp. 2–3)

That is, discrimination in pay might occur in small increments, with minor raises here and there that accumulate to a major disparity over time. Moreover, in most jobs, people don’t know how much their coworkers make, so it may not be immediately obvious to a woman when she is being paid less than her male counterpart.

The EEOC also handles claims of sexual harassment in the workplace, a topic we discuss in Chapter 14. For more information about the EEOC and employment discrimination, visit https://www.eeoc.gov/.

In one field experiment, researchers published two versions of a job ad: both versions offered the same wage, but one version said the wage was negotiable and the other version was ambiguous about the possibility of negotiation (Leibbrandt & List, 2015). The researchers measured how many men and women applied for the job and whether the applicants initiated wage negotiations. When ads were ambiguous about whether wages were negotiable, fewer women applied for the jobs and, when they did, they were less likely to initiate wage negotiations. By contrast, when ads explicitly said that wages were negotiable, more women applied and the gender difference in initiating wage negotiation was eliminated. Again, the context of having more information—such as whether a salary is negotiable—can significantly change outcomes related to the wage gap. Employers would be wise to consider this information when writing their job ads.

In sum, the evidence indicates that, while men tend to negotiate better, this difference is small and, well, negotiable. A logical extension of these findings, then, would seem to be this: We need to teach girls and women how to negotiate for higher pay. But before we jump into salary negotiation workshops, let’s reconsider the concern about female deficit interpretations and dig deeper into this pattern. Why do women, on average, negotiate for higher pay less effectively than men do?

There is evidence suggesting that, for women, salary negotiation comes with a price that goes beyond wages. Negotiating for higher pay involves expressing confidence about one’s ability to do the job well and advocating for one’s financial worth. These behaviors are consistent with the male role, which demands self-confidence, personal agency, and being a breadwinner. By contrast, these behaviors are at odds with the female role requirements of being modest and putting the needs of others ahead of one’s own needs. Thus, women tend to be more reticent to negotiate for higher pay because of the social backlash for doing so (Amanatullah & Morris, 2010; Bowles & Babcock, 2012; Rudman & Glick, 1999). Suppose Alicia is offered a job and she negotiates for higher pay, violating her gender role and others’ expectation that she should be modest and simply grateful for whatever is offered to her. The social backlash to Alicia’s effective self-advocacy would involve negative evaluations of her interpersonal qualities. In short, Alicia’s new boss and colleagues may perceive her as aggressive, out for herself, and overconfident. Who wants to start a new job under those conditions? For many women, the risk of alienating coworkers is greater than the benefit of higher pay, particularly if the opinions of those coworkers are important for job advancement.

Women aren’t imagining this risk: The research evidence supports the existence of a social backlash in the workplace (e.g., Bowles et al., 2007). A meta-analysis of the social backlash examined penalties for expressions of dominance, assertiveness, or agentic behavior and found that expressing dominance reduces women’s hirability considerably more than it does men’s, d = –0.58 (M. J. Williams & Tiedens, 2016). Moreover, making explicit or direct demands for a raise or better job benefits has a more negative effect on women’s likability than on men’s, d = –0.28. In many cases, then, it seems that women (but not men) must choose between better pay and being liked by their coworkers.

Remember that a feminist perspective always involves finding a path forward, a way to make things more equitable and just. Therefore, feminist researchers have focused their efforts on devising strategies that improve women’s pay negotiation effectiveness while avoiding the social backlash for gender role violations (e.g., Bowles & Babcock, 2012; Heilman & Okimoto, 2007). These strategies often involve women conveying their communal traits—such as interpersonal warmth and concern for the well-being of others—during the negotiation process, which reduces the perception that they are violating their gender role.

Entitlement

A related factor that may contribute to gender differences in salary negotiation is entitlement. Entitlement refers to the individual’s sense of what they should receive (e.g., pay) based on who they are or what they’ve done. If a woman thinks she is entitled to better pay, she’s more likely to ask for it. A number of studies have demonstrated that, relative to men, women have a lower sense of entitlement to pay for their work (Hogue & Yoder, 2003; Major, 1994).

What drives this gender difference in entitlement? Social psychologist Brenda Major (1994) developed a theory that explains how social structural factors and psychological factors interact to perpetuate the wage gap. The process begins with inequalities in the social structure in the United States, such as occupational segregation by gender, the chronic underpayment of women and of women’s work, and the lack of equal opportunities for women. These inequalities in the social structure then lead women and men to have different standards of comparison—that is, standards against which they compare their own pay when deciding whether it is equitable. The result is that women compare their pay with that of other women and with others in their typically female-dominated occupation. Women see other women and those in their own occupation as the appropriate comparison group because of a proximity effect—that is, those are the people who are around them and about whom they have information. The average administrative assistant is unlikely to have information on what electricians earn. Self-protective factors may also play a part. An underpaid female librarian who is a college graduate may not want to know what a male high school graduate working in a skilled trade earns. It will just make her feel bad. Her tendency will be to compare her pay with that of other female librarians, and then she won’t be doing so badly.

Cartoon 9.1

Public domain

These gender differences in standards of comparison then have a great impact on women’s and men’s perceptions of their entitlement to pay. Many women do not feel entitled to high pay for their work in the way that men do because (a) their pay is reasonable relative to those with whom they compare themselves, (b) their pay is reasonable compared with their own past pay, and (c) their pay is reasonable according to what is realistically attainable given restricted job opportunities for women.

The result is that women have less of a sense of entitlement to high pay than men do. This in turn leads them to tolerate wage injustice. Another consequence is that others come to believe that women will settle for less in pay, precisely because many women do, leading to further bias in setting wage rates. And so the cycle continues.

What evidence is there to support this theory? Many experiments have been conducted testing various aspects of it, and virtually all of them support it. In one study (O’Brien et al., 2012), female and male undergraduates were given 20 minutes to circle every letter e they could find in a legal document. In a self-report measure of entitlement, participants were asked to report how much they thought they deserved to be paid for their work. The researchers also measured entitlement by observing the participants’ behavior. Participants were initially paid $8 for the work, and they were also given the option of awarding themselves bonuses. Participants paid themselves bonuses privately from an envelope containing $5. The gender differences were striking: Not only did men report that they deserved higher pay than did women (d = 0.75), but they also paid themselves higher bonuses (d = 0.63). Yet, compared with men, women actually completed more work and did so with greater accuracy! Thus, men’s greater entitlement couldn’t possibly have resulted from doing superior work.

As we noted in Chapter 1, we must be careful of interpretations of these phenomena, so that this theory does not become another female deficit model. One interpretation is that women have a low sense of personal entitlement compared with men—that is, that women have a deficit in their sense of entitlement. The other possible interpretation is that men have an inflated sense of entitlement—a sense that they are entitled to more than they are worth. An inflated sense of entitlement characterizes many dominant groups, including men, White people, and people from upper social classes (O’Brien & Major, 2009). In an interesting twist, researchers have been able to manipulate men’s (but not women’s) sense of entitlement by priming their belief in meritocracy (O’Brien et al., 2012). That is, members of dominant groups feel more entitled when they’re reminded of beliefs that justify or seem to legitimize the systems of inequality that perpetuate their dominance. Yet this effect does not occur for members of subordinate groups.

Photo 9.4 How can women feel entitled to higher pay and effectively negotiate for a fair wage while avoiding the social backlash for violating their gender role?

©iStockphoto.com/asiseeit.

The research on entitlement is an excellent example of the ways in which social structural factors, such as the gender segregation of occupations, are linked to psychological processes, like sense of entitlement, to create gender bias.

Implicit Stereotypes

New research points to another factor that may be behind the wage gap: implicit stereotypes. In Chapter 3 we discussed implicit stereotypes, or learned, automatic associations, and how they are measured with the Implicit Association Test (IAT). Researchers have used the IAT and uncovered automatic associations between the category of “male” and the category of “rich” (Williams et al., 2010). That is, people may possess implicit stereotypes that men (not women) may be rich. Moreover, when the participants in this study were asked to estimate the salaries of men or women in different occupations, they tended to estimate higher salaries for men than for women. This tendency to overestimate men’s salaries was linked to the participant’s implicit stereotypes.

Other studies have found that implicit stereotypes about gender and leadership are linked to the evaluation of women’s and men’s work (e.g., Latu et al., 2011). This research points to another layer of psychological factors that may contribute to the wage gap. Recall that implicit stereotypes are not conscious; thus, a manager may believe they are fair and equitable in determining salaries or wages, but their implicit bias may still lead them to make unfair decisions. Still, conscious forms of bias and discrimination may also contribute to the wage gap.

Gender Discrimination and Workplace Climate

Gender discrimination in the workplace may take several forms, including gender discrimination in job ads, in hiring decisions, in pay, and in the evaluation of work, as well as phenomena such as the glass ceiling. Sexual harassment is also a tool of sexism in the workplace, but we will discuss that in the context of gender-based violence in Chapter 14.

Gender Discrimination in Job Advertisements

Often, the first step in the employment process is the job ad. There is a long history of gender discrimination at that initial stage. For many years, newspapers published job ads in two sections distinguished by gender: Jobs for Men and Jobs for Women. The Jobs for Women were largely clerical and invariably low-paying. Women were explicitly told that they should not bother applying for the higher-paying jobs reserved for men. It was old-fashioned sexism, and today it’s shocking. The courts then ruled that it was illegal to advertise jobs for just one gender and newspapers switched to having a single section of job ads.

Yet today we grapple with the subtle ways of modern sexism, which is just as inequitable yet often more difficult to identify. For example, job ads often include gendered wording. One study found that ads for male-dominated occupations contained significantly more masculine words (e.g., leader, competitive, dominant; Gaucher et al., 2011). In follow-up laboratory experiments, the researchers asked participants to read job ads that were identical except for masculine or feminine wording. For example, in the ad for a real estate agent, the feminine wording said, “We support our employees with an excellent compensation package,” whereas the masculine wording said, “We boast a competitive compensation package.” When the ads included more masculine words, participants estimated that there were more men in the occupation. In addition, female participants found such jobs less appealing, largely because they felt less sense of belonging in jobs advertised with masculine wording. That is, with masculine wording, women felt less like they belonged in that job, compared with feminine wording. This research demonstrates how subtle forces can maintain occupational segregation by gender and discourage women from applying for certain occupations. If we don’t think we belong in a job, why would we apply for it?

Gender Discrimination in the Evaluation of Work

Psychologists have made important contributions to the study of gender discrimination in the evaluation of work over many years. For example, a classic experiment demonstrated that even when a woman’s work was identical to a man’s, her work was judged to be inferior to his (Goldberg, 1968; replicated by Pheterson et al., 1971). Participants read and evaluated essays written either by a male author (e.g., John T. McKay) or a female author (e.g., Joan T. McKay). The essays were identical except for the names of the authors. Results showed that essays by male authors were rated more highly than essays by female authors, even when the topic of the essay was traditionally feminine (e.g., dietetics). In other words, the work of a man was judged better than that of a woman, even when the work was identical in quality.

Since that classic experiment, several meta-analyses of similar experiments have been conducted (e.g., Davison & Burke, 2000; Koch et al., 2015; Swim et al., 1989). In general, these meta-analyses have found little evidence of bias in the evaluation of women’s work. For example, the most recent meta-analysis reported an average effect size of d = 0.08, indicating that men’s work was given slightly higher ratings than women’s work, but the d was so small that we could say it was zero (Koch et al., 2015). Notice that—in contrast to other meta-analyses we have reported, in which d reflected the difference between the performance of men and the performance of women—here the effect is for the difference between evaluations of work with a man’s name on it and evaluations of work with a woman’s name on it. The effect size d, in this instance, is a measure of the extent of gender bias or discrimination.

Wouldn’t it be satisfying to say that women’s work is evaluated fairly and that gender bias is no longer a problem? Yet, as is often the case, the moderator analyses reveal complexities in the data and tell us that there is much more to this story (Koch et al., 2015). For example, the gender bias was greater in jobs that were male-dominated (e.g., police officer) than in jobs that were female-dominated (e.g., teacher), d = 0.13 versus d = –0.02. That is, gender bias depended on whether the job appeared congruent with the gender role of the applicant or employee. In addition, men tended to have more gender-biased ratings than women did.

Another layer of complexity in the data was that gender bias depended on how much information the rater had about the applicant or employee. For example, when raters were given only a small amount of information—maybe just a male or female name—there was more gender bias (favoring men) than when raters were given more information (Koch et al., 2015). This is consistent with a general finding in social psychology that people stereotype others less the more they know about them.

Yet an important limitation in these meta-analyses was that nearly all the studies reviewed were laboratory experiments with college students serving as the raters. In short, the studies do not directly measure what really matters: Gender discrimination in the actual evaluations of real work done by real people. Such experiments don’t tell us about gender bias and discrimination in the evaluations conducted by supervisors, by people actually making hiring decisions, or by other powerful persons. The laboratory experiments in these meta-analyses provide only analogies to the real situation, and for that reason they are called analog studies. We are left wondering how much gender bias shapes real hiring decisions and whether it contributes to the wage gap.

In Chapter 8 we described an experiment using a similar design with science faculty rating job applications for a lab manager position (Moss-Racusin et al., 2012). That experiment demonstrated that the equally qualified man not only was rated as more competent and hirable but also was offered a higher starting salary and more career mentoring. Studies like this provide more reliable evidence of gender discrimination in the evaluation of women’s work and have alarming implications for the wage gap. In addition, because this study was conducted with people with the power to make hiring decisions, it addressed the limitation of previous laboratory experiments conducted with students.

Workplace Climate

The problems of discrimination and harassment have much to do with the climate of a workplace. For example, is the climate or general environment and culture of a workplace one that promotes fair and equitable treatment of all employees? Or is it one that permits and fosters microaggressions, indirect aggression, and feelings of exclusion or anxiety?

Workplace climate matters for everyone’s job satisfaction, productivity, and well-being, of course, but it is a particular concern for individuals from marginalized groups, such as sexual and gender minority groups. While U.S. federal laws currently do not provide clear protections for members of such groups in the workplace (see Focus 9.1), corporate America has led a shift toward more inclusive nondiscrimination policies. For example, 91% of Fortune 500 companies explicitly include sexual orientation in their nondiscrimination policies, and 61% include gender identity (Fidas & Cooper, 2015). In addition, many employers have extended benefits to members of sexual and gender minority groups in an effort to recruit and retain the most talented and qualified employees, no matter their sexual orientation or gender identity. Simply put, it’s good business to make all employees feel valued and protected at work!

Still, more subtle aspects of the workplace climate, such as coworkers’ implicit stereotypes and microaggressions, remain problematic for many individuals from sexual and gender minority groups. For example, one national study surveyed lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people and found that more than half reported hiding their sexual orientation or gender identity in the workplace, and more than one-third reported feeling compelled to lie about their personal lives at work (Fidas & Cooper, 2015). Yet it is the norm across workplaces for coworkers to discuss personal topics such as their weekend plans, children, or romantic relationships. So, while coworkers have such non-work-related conversations, members of sexual and gender minority groups feel compelled to keep quiet or closeted. Their concerns are well founded: The same national study found that 70% of non-LGBT respondents said it was “unprofessional” to talk about sexual orientation or gender identity at work. A workplace climate that tolerates only cisgender, heterosexual employees talking openly and honestly about their personal lives is one that excludes members of sexual and gender minority groups. Whereas a workplace climate that is inclusive and accepting retains its LGBT employees, 9% of LGBT employees surveyed said they’d left a job because the workplace climate was not accepting. Of course, not everyone has the means to leave a job because of workplace climate.

Leadership and the Glass Ceiling

On November 9, 2016, after losing the U.S. presidential election, Hillary Rodham Clinton stated in her concession speech, “I know we have still not shattered that highest and hardest glass ceiling, but some day, someone will, and hopefully sooner than we might think right now.” Throughout Clinton’s presidential campaigns in 2008 and 2016, the glass ceiling was discussed in the popular media. The term is a metaphor used to describe the barrier or ceiling that prevents women from advancing to the highest-level jobs, including the presidency. Women may be promoted and move up the ranks in their company, but there is a point past which they can’t seem to rise any further. For example, some women make it to the upper levels of management, but don’t break into executive positions in the C-suite—they can see the highest levels through the glass ceiling, but they can’t break through it.

Photo 9.5 In the 2016 presidential election, Hillary Rodham Clinton won the popular vote but lost the election, and the “highest and hardest glass ceiling” remained intact.

The Washington Post/Getty Images.

What evidence is there that a glass ceiling exists? A study of S&P 500 companies found that although 44.3% of all employees in these companies were women, women made up only 25.1% of executives and managers (see Figure 9.1). At the highest level of the company, less than 5% of CEOs were women. These data indicate that the higher one goes in corporations, the fewer women (and, often, people of color) one will find. This pattern clearly demonstrates the glass ceiling.

The glass ceiling hurts everyone. Corporations with more women at the top actually perform better than other corporations. One study examined a sample of 353 Fortune 500 companies and found that those with the highest representation of women in top management showed better financial performance than the companies with the lowest representation of women (Catalyst, 2004). Breaking the glass ceiling isn’t just good for women; it’s good for business.

Leadership Effectiveness and Gender Role Congruity

We’ve discussed how discrimination can lead to a shortage of women in leadership positions, but we should also explore whether and how women can be successful when they reach those leadership positions. In real-world job situations, women might be perceived as ineffective leaders, managers, and supervisors for various reasons. One possibility is that women are truly lacking in the abilities, personality traits, interpersonal skills, and so on that are necessary to be successful in the leadership role. Another possibility is that, regardless of whether women are actually effective in leadership roles, they are judged or evaluated unfairly; that is, people are biased in their evaluations of female leaders.

Figure 9.1 Statistics on the glass ceiling: As the level at S&P 500 companies increases, the percentage of women decreases.

Source: Catalyst (2016). Figure created by Nicole Else-Quest.

Let’s consider the evidence for these possible explanations. In regard to the first hypothesis—whether women can do the job—research generally shows no gender differences in the actual effectiveness of leaders. Eagly and her colleagues (1995) conducted a meta-analysis of studies of the effectiveness of leaders and found that the magnitude of the gender difference in leadership effectiveness was d = –0.02. In other words, there was no gender difference. Leadership effectiveness can be measured either subjectively, as when a manager’s skills on relevant dimensions are rated by other managers, or more objectively, as when the productivity of a leader’s group is assessed. The results were similar with subjective measures (d = 0.05) and objective measures (d = –0.02). Still, in some situations, female leaders may be more effective than male leaders, and vice versa. When the leadership position was consistent with the female gender role, female leaders were judged as more effective. Similarly, when the leadership position was consistent with the female gender role, female leaders were more effective.

The second hypothesis is that people are biased in their evaluation of female leaders. A meta-analysis of laboratory studies evaluating women and men in leadership roles generally found little evidence of gender bias when all other factors were controlled (Eagly et al., 1992). That is, female and male leaders were given similar evaluations (d = 0.05). Yet this finding was qualified by leadership style: Under certain conditions women received notably poorer evaluations. If women used an autocratic or dictatorial leadership style rather than a more democratic and nurturant style, they received lower evaluations (d = 0.30). It may be, then, that it is not so much a question of bias against women leaders as bias against women leaders who do not behave in a style consistent with their female gender role. The female gender role requires that women be gentle, nurturant, and cooperative, not assertive, confrontational, or bossy. People have trouble with autocratic, pushy women, while men who engage in the same behaviors are not judged as harshly. This is the social backlash discussed earlier; women’s dominant behavior is perceived negatively because it violates their gender role. These are important findings for women as they assume leadership roles and consider the management style they adopt.

Social psychologist Alice Eagly has proposed a role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders (Eagly & Karau, 2002). The theory holds that people tend to perceive an incongruity or incompatibility between leadership behaviors and the female gender role. This perceived incongruity in turn leads to two forms of prejudice. First, people perceive women less favorably than men as potential occupants of leadership positions. This gives women less access to leadership opportunities. Second, when women engage in leadership behavior, the behavior is evaluated less favorably than the same behavior enacted by a man. One implication is that female managers who engage in behaviors that, objectively, represent effective leadership may nevertheless be ineffective as leaders because subordinates react negatively to that kind of behavior coming from a woman.

Taking an intersectional approach to gender and leadership, we must consider how race or ethnicity can shape the evaluation of women and men in leadership positions. In some cases, being marginalized or lower status on multiple social categories—such as being both Black and a woman—means facing double jeopardy, in which the multiple disadvantages are combined or amplified. By contrast, sometimes the effects of low status in one category might cancel out the effects of low status in another category. For example, we might ask what happens when a woman of color displays agency or dominance. Is the role incongruity and social backlash to her behavior similar to or different from that faced by White women? One study compared evaluations of leaders at the intersection of race and gender, asking participants to rate leaders who were (a) Black or White, (b) female or male, and (c) dominant and assertive or communal and compassionate (Livingston et al., 2012). The participants rated the effectiveness and expected salaries of the leaders. The researchers found that White men and Black women were rated similarly regardless of their behavior, while Black men and White women were penalized for expressing dominance. In short, the gender role incongruity, and subsequent social backlash, was defined differently based on race. Reflecting on the complexity of these findings, the researchers cautioned that Black women and White women likely face some unique barriers and bias in the workplace as well as some similar ones. In addition, because gender and racial stereotypes are intertwined, the perceived gender role incongruity of dominance or assertiveness depends on gender as well as race (Rosette et al., 2016). This is an exciting and important area of research as we continue to use an intersectional approach to explore how the glass ceiling impacts women from diverse backgrounds.

Are We Making Any Progress?

Feminists have been talking about the glass ceiling for decades now. Have things gotten better? Yes and no. Social psychologists Alice Eagly and Linda Carli (2007) have argued that barriers to women’s advancement today are more permeable than the rigid, impenetrable barrier suggested by the glass ceiling metaphor. Instead, they propose that a labyrinth is a more apt metaphor for women’s advancement in corporations. That is, today women can make it to the top, but they often have to do it by navigating complex and sometimes indirect paths, much like maneuvering through a labyrinth. Improved opportunities for women have been created by several trends. One of these is changing definitions of leadership in corporations. The old image of the dictator boss has, in many sectors, been replaced by an ideal of transformational leadership in which the leader motivates and mentors employees. The dictator boss model did not work well for many women, but the transformational leader model does. Moreover, women are rated more highly than men on many of the characteristics of transformational leadership (Eagly et al., 2003).

Photo 9.6 Women aspiring to nontraditional careers may face various forms of bias and discrimination; for example, some people have difficulty recognizing a woman—especially a Black woman—in a leadership role. This photograph shows a woman attorney and her client. When you saw the picture, did you perceive him as being her boss?

©iStockphoto.com/kali9.

Nonetheless, the data are clear that there remain barriers preventing or hindering women’s advancement in corporations. Progress has been slow in this area. Still, in certain fields, women have quickly risen to earn substantial numbers of professional degrees. Some statistics from professions in which women have made some of the greatest advances are shown in Table 9.3. Now that women are earning so many of the professional degrees in these areas, occupational segregation will surely decrease. It is particularly interesting to note that all of these are high-paying, high-status occupations. Education can be one of the most important solutions to the problems women face in the workforce.

You may be interested in which jobs pay the best for women. The top four are pharmacists, lawyers, computer software engineers, and physicians (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2011b).

Work and Family Issues

The female gender role has always centered on maintaining the family and providing care to children. During the second wave of feminism in the 1970s and 1980s, women marched into the paid workforce, adding the responsibilities of paying jobs to their workload. Yet this all happened while women maintained their family responsibilities. In turn, the issue of combining work and family emerged. It remains one of the most important social issues in the 21st century, especially for women. Work and family issues rank high on the feminist agenda, and corporate executives realize their importance. Even the U.S. government has recognized the centrality of this issue for families; legislation on parental leave went into effect in 1993 (see Focus 9.2).

Work and Women’s Psychological Well-Being

The average American woman today holds a full-time job while managing a household and a marriage and raising a child or caring for an elderly relative. Is she on overload, stressed out with all her responsibilities, prone to physical and mental illness? Or is she Supermom, able to have it all and be happy? The answer is somewhere in between these extremes, often complicated by structural and political factors.

Social scientists have asked important questions about the effects of multiple roles (e.g., worker, spouse, parent) on well-being. Broadly speaking, researchers in this area have taken two major theoretical approaches(Barnett & Hyde, 2001).

One approach proposes the scarcity hypothesis, which assumes that each person has a fixed amount of energy and that any role makes demands on this pool of energy. Therefore, the greater the number of roles, the greater the strain on their energy and the more negative the consequences on well-being. The conclusion from this view, then, is that as women take on increased work responsibilities in addition to their family responsibilities, stress and negative mental and physical health consequences must result.

Photo 9.7 Work/family issues are among those at the top of the feminist agenda. Does combining work and motherhood serve as a source of stress, or does it enhance women’s well-being?

©iStockphoto.com/monkeybusinessimages.

An alternative approach proposes the expansionist hypothesis, which assumes that people’s energy resources are not limited and that multiple roles can have benefits for well-being. That is, just as a regular program of physical exercise makes one feel more energetic, not less energetic, multiple roles can be beneficial. According to this approach, the more roles one has, the more the opportunities for enhanced self-esteem, stimulation, social status, and identity (Barnett & Hyde, 2001). Indeed, one might be cushioned from a traumatic occurrence in one role by the support one is receiving in another role.

If the scarcity hypothesis is correct, then Maria is likely to feel stressed and overwhelmed by the demands of multiple roles when she takes on a paying job while her child is at day care or school. By contrast, if the expansionist hypothesis is correct, Maria is likely to feel greater self-esteem and personal fulfillment from her multiple roles. Alternatively, it might also be true that both of these theoretical approaches have some validity.

Actual research on the effects of paid employment on women’s health paints a generally positive, but also complex, picture (Barnett & Hyde, 2001; Perry-Jenkins et al., 2000). In general, employment does not appear to have a negative effect on women’s physical and mental health. Actually, employment seems to improve the health of both unmarried women and married women who hold positive attitudes toward employment. By being employed, Maria might gain social support from her colleagues and supervisors, as well as opportunities for success or mastery. She can develop and use different skills at work that she might not use at home, and vice versa. Factors such as opportunities for mastery and social support seem to be important to the health-enhancing effects of employment for women.

Of course, many women are not in such ideal situations. If Maria is underpaid relative to her male colleagues or if she is sexually harassed by her supervisor, she probably won’t experience positive health benefits from employment. And, as income inequality persists and grows in today’s economy, many work-family issues are highlighted at the intersection of gender and class. For example, poor or low-income families have few choices when it comes to finding sustainable work-family arrangements. If Maria’s job has little flexibility in hours or a stingy leave policy, she’ll have few options when her child gets sick and needs to stay home from school. Moreover, if Maria lacks a college education or a skilled trade, she may not have access to a better job. These factors make it less likely that poor or low-income women will find benefits from multiple roles.

A critical factor in the relation between employment and women’s well-being is child care. If a mother cannot find child care, or if she feels that the available sources do not offer high-quality care for her child or are so expensive that she cannot afford them, then combining work and motherhood becomes stressful. Maria might question the value of working if the bulk of her wages go to child care or if the child care is of poor quality. Alternatively, if the child care she can afford is excellent, and she feels that her child is thriving while she’s at work, then work and family roles are more likely to enhance each other.

These complexities demonstrate the importance of the quality of roles, not simply the quantity of them. Clearly, combining multiple low-quality roles isn’t likely to help anyone. But a high-quality role that elicits joy, pride, or happiness can make a big difference in one’s life, especially if other roles are less satisfying.

Researchers have proposed two processes by which multiple roles might contribute to our well-being in both positive and negative ways. One such process is spillover, in which positive or negative feelings in one role might carry or spill over into another role. For example, if Maria has a productive day at work, she might bring feelings of accomplishment and satisfaction home with her, being in a generally positive mood when she interacts with her child. Spillover could also be negative, such as when her child has a tantrum at preschool drop-off, putting Maria in a bad mood just as she starts her workday. Another possible process is compensation, in which positive aspects or rewards from one role compensate or make up for the stresses or costs in another role. For example, Maria’s supportive and loving relationship with her partner might compensate for the stresses she’s been enduring at work.

Focus 9.2 Psychology and Public Policy: Family Leave

In 1993, the United States passed the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA). Prior to that legislation, the United States was one of only two industrialized nations in the world (the other being South Africa) that did not have a nationally legislated policy on parental leave. Parental leave refers to leave from work for purposes of recovering from childbirth and/or caring for a newborn, adopted, or foster child. An even broader term, family leave, also includes caring for a family member (such as an ill spouse or parent). Medical leave refers to attending to one’s own medical condition. FMLA covers family and medical leave. Until FMLA was passed, in all but a handful of states a woman could give birth to a baby and return to work quickly—say, a month later—only to find that she had lost her job, and it was perfectly legal for her employer to have fired her for not working. There was an urgent need for legislation that ensured parents the right to care for a newborn infant and know they had their jobs waiting for them; among other things, they obviously need the income to support the baby.

FMLA requires that employers allow employees a minimum of 12 weeks of job-guaranteed, unpaid leave at the time of a birth or adoption. FMLA has several important features to note. First, it is gender fair—that is, all parents have equal rights to take the leave, regardless of their gender, and some couples might choose to take the leaves back to back so that the child has a parent at home with them for a total of 24 weeks, or nearly 6 months. Yet, for most families, this isn’t feasible (as we explain below). A second feature is that the leave is job guaranteed, which means that the employee has a right to return to the same or a comparable job (in terms of pay and responsibilities) after their leave. A third feature is that the leave can be unpaid, at least as a minimum standard. Most couples cannot afford to lose one member’s income for very long, if at all, and even fewer couples can afford to lose both members’ income for any period of time. Thus, most families find it’s not feasible to take back-to-back leaves totaling 24 weeks. A fourth feature is that the legislation sets a minimum standard. Employers can choose to be more generous. It’s like the minimum wage—if it is $7.25 per hour, employers are perfectly free to pay a highly skilled person $20 per hour; they just can’t pay anyone less than $7.25. In the same way, employers can be more generous with parental leave. They can allow more than 12 weeks and they can provide paid leave. Some progressive corporations have realized that it is beneficial to provide paid leave and are already doing so.

This legislation could be improved in a number of ways to support parents. Providing paid leave is a major necessary improvement. Several states—including California, Rhode Island, New Jersey, and (starting in 2018) New York—have passed additional family leave legislation mandating paid leave. Employers worry about how costly this would be to them, but these states have solved this problem as Canada has, using a small payroll tax paid by employees and then administered by their disability programs. A second improvement that is needed is to expand coverage to employees at small businesses. FMLA applies only to employers with 50 or more employees. Women work disproportionately for small businesses, and it is important to extend the coverage to all parents.

Psychology played an important role in developing and passing FMLA. Often, as Congress considers legislation, it calls on expert witnesses, such as psychologists, who can provide evidence on the need for the legislation and the potential impact that it might have. Developmental psychologists had a wealth of knowledge to share. For example, decades of research with families led to the consensus among psychologists that infants need to spend at least the first 4 months of life with a stable caregiver who can provide consistent, sensitive, and responsive care (Brooks-Gunn et al., 2010; Zigler & Frank, 1988). This stability helps infants establish a predictable routine with a reliable caregiver, regulate body processes like sleeping and eating, and ultimately form secure attachments to their caregiver. Therefore, psychologists testified before Congress that legislation should provide 4 months of parental leave to meet the important developmental needs of an infant. This expert testimony on psychological research was influential in the passage of the bill.

If parental leave is beneficial for babies, what effects might it have for parents? Feminist psychologists immediately noticed that the well-being of mothers was invisible in the parental leave debate. So they conducted a large-scale research project that adds a second focus to the psychological research: the effects of parental leave, or the lack of it, on mothers and fathers (Hyde & Essex, 1991; Hyde et al., 1993; Hyde et al., 1995). The researchers found that, in that sample, fathers took an average of 5 days of leave and mothers took an average of 8 weeks. The researchers studied the impact of taking a short leave (6 weeks or less) compared with a long leave (12 weeks or more) on women’s mental health. They found that a short leave can act as a risk factor for mental health problems: When a short leave is combined with some other risk factor such as a stressful marriage or a stressful job, problems such as depression result. For example, women who took short leaves and had many concerns about their marriages had elevated levels of depression, compared with women who took longer leaves or who took short leaves but had happy marriages. They also found that many of the women in the sample wished they could have taken a longer leave than they did. The leading reason why they didn’t take a longer leave was that they could not afford to do so. Parental leave also affected whether and how long mothers breastfed their babies. In short, many families wanted to take parental leave, and longer leave was beneficial for families.

This research and the research of developmental psychologists on infants’ attachment needs illustrate how important psychological research can be in framing legislation that will have an impact on most of us at some time in our lives.

Sources: Berger et al. (2005); Brooks-Gunn et al. (2010); Gale (2006); Kamerman (2000); Waldfogel (2001).

The Second Shift

In her book The Second Shift: Working Parents and the Revolution at Home, sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild (1989, 2012) wrote about the rewards and challenges of working while raising a family. The book is based on her qualitative research with dual-earner couples with children—that is, two-parent households in which both parents work. And, as with nearly all of the research on dual-earner couples, all of the couples in Hochschild’s sample were cisgender and heterosexual. She found that most employed mothers put in a full day of work on the job and then return home to perform a second shift of house and family work. By contrast, employed fathers did not work a second shift.

She also described studies from the 1970s concluding that, if “work” is defined as including work for pay outside the home plus work done in the home, then women worked, on average, 15 hours more per week than men did (Hochschild, 1989, 2012). Thus, over the course of a year, women worked an extra month of 24-hour days!

The problem of multiple roles for women is more than just a question of hours and quantity of roles. Hochschild found that women were also more emotionally torn between the demands of work and the demands of family. In addition, the second shift creates a struggle in some marriages. The wife, in many cases, struggles to convince the husband to share the housework equally; alternatively, she does almost all of it and resents the fact that she does. And even when husbands contribute to some of the housework, women are still responsible for all of it. In addition, much of the work the women were doing—in particular, caring for children and other relatives—was undervalued.

Hochschild concluded that we are living in a time of transition amid a social revolution in which gender roles are in flux. She described this as a “stalled revolution” in which women have been catapulted into the world of paid work even as men have not shown an analogous move into caring for children and the home environment. In this period of transition, we have not yet arrived at stabilized new social structures that promote and maintain gender equality.

While Hochschild’s arguments were challenged by some researchers (e.g., Gilbert, 1993; Pleck, 1992), other research supports her conclusions. One question is whether Hochschild adequately took account of changes over the last few decades. Men’s contributions to family work have increased from 1970 to the present, yet the change has been gradual and there is still not gender equity. Women have adapted, in large part, by altering the way they spend their time. In particular, women today spend as much time with their children as they did in the 1960s (Bianchi & Milkie, 2010). The dramatic change has been in the amount of time spent in housework. Today, survey data show employed married women spend only 1.6 hours per day on housework, compared with 1 hour per day spent by husbands (White House Council on Women and Girls, 2011). That is unequal, but it hardly seems like a second shift. Overall, the gender gap in housework and child care appears to have narrowed substantially over the past few decades (Bianchi & Milkie, 2010).

Yet these studies have largely relied on survey data, in which researchers ask people to estimate how much time they typically spend on housework and child care each week. Such surveys are problematic for at least two reasons: They don’t take into account multitasking (i.e., doing more than one activity at a time), and people’s estimates of their time use in the past week are often unreliable. Another measure is to ask participants to complete time diaries, in which they record how they use their time throughout a given day. Time diaries are more reliable and accurate because they include more detail, can take multitasking into account, and ask participants to remember only one day at a time.

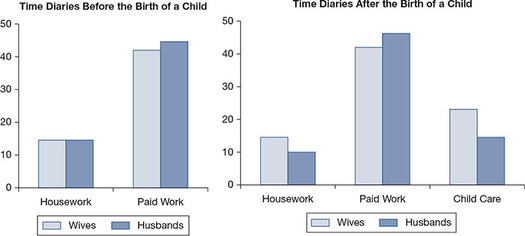

In one longitudinal study, researchers asked heterosexual dual-earner couples to complete both surveys and time diaries of their time spent in paid work, housework, and child care (Yavorsky et al., 2015). The researchers were interested in how the division of labor within couples changed after having a baby, so they asked couples to complete the measures during the third trimester of pregnancy and then again when the baby was 9 months old. Results showed that having a baby didn’t change how much time wives and husbands spent in their paid jobs: Before and after the birth, husbands spent about 2.5 hours more per week at work (see Figure 9.2). However, time diaries told a different story when it came to housework and child care. Prior to the birth, husbands and wives shared equally in their housework; after the baby arrived, wives spent 4 hours more than husbands did on housework each week. And, compared with their husbands, wives spent nearly 8 hours more on child care each week. In other words, the birth of a child resulted in a greater workload at home for wives and husbands, but wives did a greater share of that work. This isn’t exactly a second shift, but it amounts to nearly 2 hours more work at home each day for women.

Some researchers have pointed out that the type of housework husbands and wives tend to do differs in terms of when it needs to be done and how often (Hook, 2010). Routine housework is more demanding of time and energy than nonroutine housework, and routine housework is more likely to be done by women. For example, dinner needs to be made every night and within a particular window of time, but mowing the lawn or changing the oil in the car can be done less often and when it’s convenient.

Figure 9.2 The division of household labor changes after the birth of a child in heterosexual dual-earner couples.

Source: Yavorsky et al. (2015). Figure created by Nicole Else-Quest.

Attitudes about gender roles and the importance of women’s paid employment have also changed since Hochschild’s original work. Today, many couples aspire toward an egalitarian division of labor. Yet only about one-third of dual-earner couples share in the paid work, housework, and child care equally (Gilbert & Dancer, 1992). An important factor for the marital satisfaction of dual-earner couples is the perception of fairness in the division of labor (Coltrane & Shih, 2010). For some couples, equity in work does not necessarily require equality in work.

Overall, work–family arrangements in the 2lst century have continued to evolve and are shaped by two trends: increasing diversity in families and increasing diversity in the nature of work and workplaces (Bianchi & Milkie, 2010). Heterosexual married couples have long been described as the norm, but there are increasing numbers of single parents with children, cohabiting couples, queer couples, and divorced parents with children. The research on the division of household labor in lesbian and gay couples indicates that these couples tend to have more egalitarian arrangements than heterosexual couples (Goldberg, 2013). That is, household tasks are divided more equally between same-gender partners, who also tend to be more attentive and sensitive to issues of equality within their relationships. Finding the right work–family arrangements is likely challenging across each of the diverse family arrangements in America today, but work–family researchers have not yet studied each of these in equal depth.

In parallel, work arrangements have become more complex, in part because of the trend toward a 24/7 economy, in which some businesses are expected to be open at all hours. That trend puts increasing pressure on employees to work in nonstandard arrangements, such as teleworking and evening shifts. And communication and information technologies, including e-mail and texting, often presume that workers, even when at home, are constantly available. In many of these cases, the boundaries between work and home have become blurred, which makes spillover more likely.

Experience the Research: Entitlement

In this exercise you will investigate Brenda Major’s notion of entitlement and how it is related to the gender gap in wages.

Interview four psychology majors, two men and two women, preferably seniors. In each case, read them the following paragraph:

Imagine that you have just graduated with your degree in psychology. You want to get some research experience before deciding whether to go to graduate school. You manage to land a job as a full-time research assistant in the laboratory of a professor at the University of Wisconsin. What do you think your pay would be for your first year at that full-time job? How did you come up with that number—that is, what factors did you take into account?

Write down the gender of your respondent, their estimate of pay (be sure to get it in terms of an annual salary, not an hourly wage), and their reasoning about the pay.

Were your results consistent with Major’s theory of entitlement? Did the men estimate higher salaries than the women? What factors did the women take into account in deciding on the salary? Were these factors different from the men’s?

Chapter Summary

This chapter reviewed the research on how, across ethnic groups, the gender gap in wages persists and what factors might contribute to that gap, including occupational segregation, compensation negotiation, and implicit bias. Discrimination and the climate are also important considerations in gender equity in the workplace. The glass ceiling continues to prevent women from serving in leadership positions, as the leadership role seems incompatible with femininity. Moreover, federal laws regarding gender discrimination and family leave do not provide adequate protection and support for women and individuals from gender and sexual minority groups. What directions do we need to take for the future?

A combination of private change and public change is needed to foster gender equity and help all people find productive and satisfying work. In the private realm, gender roles must continue to change so that men contribute equally to and feel equal responsibility for household and child care tasks. In the public realm, some states and corporations have led the way in protecting gender and sexual minority groups against workplace discrimination, but federal protections are long overdue. We must have pay equity so that all people are paid fairly for the work they do. In addition, we need new social policies planned by the government that provide real support for dual-earner families—policies that are truly pro-family. The U.S. government urgently needs to promote high-quality, affordable child care. It also needs to devise a system to provide paid parental leave for new mothers and fathers, and opportunities for part-time work, flextime, telework, and job sharing so that working parents can successfully manage their multiple roles.

Suggestions for Further Reading

Eagly, Alice H., & Carli, Linda L. (2007). Through the labyrinth: The truth about how women become leaders. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press. Psychologists Eagly and Carli assembled the evidence about women climbing the career ladder, concluding that a labryinth is a better metaphor than the glass ceiling.

Slaughter, Anne-Marie. (2015). Unfinished business. New York, NY: Random House. The first female director of policy planning at the U.S. State Department writes about the importance of caregiving and how public policy can promote gender equality in work and family responsibilities.