Introduction

USING THIS GUIDE

Divided into six parts, this guidebook is designed for planning your Everglades trips and for use in conjunction with navigational charts while you are paddling.

Part One leads you on a thru-paddle of the Everglades Wilderness Waterway, with detailed information for trip preparation. The thru-paddle itinerary is presented in 21 sections of text, with 21 full-page maps juxtaposed for your convenience. The maps guide you both north to south and south to north between the put-in and takeout points in Everglades City and Flamingo. (Map 22, The Historical Route, presents the original, though not recommended, passage across Whitewater Bay.)

Part Two describes day and overnight paddles (with suggested campsites) in the north end of Everglades National Park. Each of those paddles launches from and returns to Everglades City. No shuttles are required.

Part Three guides you on day and overnight paddles (and suggested campsites) in the south end of the park, launching from either the park road west of Homestead or from Flamingo. As with the trips from Everglades City, no shuttles are required.

In both Parts Two and Three, we open each day trip or overnight excursion with an overview of six key items:

| ► | the waterway or destination name |

| ► | distance in miles |

| ► | estimated paddle time in hours |

| ► | potential hazards |

| ► | GPS coordinates for significant points on that route |

| ► | navigational references |

Then we provide a brief description of each route and a run profile with commentary on the human history and flora and fauna of the area. Regarding the paddling duration given for these day and overnight trips, all times are approximate, depending on several factors: your paddling speed, whether you are moving with or against the tides, and, not to be overlooked, the number and length of breaks and photo stops along the way.

The potential hazards we cite in the overviews in Parts Two and Three include oyster beds, mudflats, strong currents, and other tide-related occurrences; wind and waves in open water; heavy boat traffic; wet and dry cycles; and hurricane season. (But we will remind you here and elsewhere to always check with the visitor centers for current conditions on your chosen routes.)

Part Four describes the particular challenges of summertime paddling in the Everglades.

Part Five describes the campsites that are cross-referenced in the Wilderness Waterway section (Part One) and in the overnight descriptions (Parts Two and Three).

Part Six provides interesting information about the natural and social history that will become part of your Everglades experience.

THE MAPS

The maps in this guidebook show put-in and takeout points; campsite locations; navigational markers; historical sites; and significant islands, bays, and streams. While these maps are exceedingly helpful to you as you plan and paddle the routes, do not rely solely on them for navigation. You will be traveling through intricate interlacings of mangrove islands and waterways. For safety’s sake, you must carry navigational charts if you undertake the full Everglades Wilderness Waterway. Charts are not as necessary for day trips, although they are always helpful as an extra precaution.

ROUTE DESCRIPTIONS

For the grand, 99-mile journey along the full length of the Everglades Wilderness Waterway, or even for a significant portion of it, the location of campsites and route paddling conditions described in this guide will help you determine an appropriate itinerary. Run profiles for short paddles from Everglades City or Flamingo offer choices; some lead you into the wilderness, and some keep you closer to civilization. Either way, you’ll find paddles for varying skill levels and interests.

GPS COORDINATES

We used a Global Positioning System (GPS) receiver to pinpoint the coordinates, or intersection of latitude and longitude lines, along each route or at each destination referenced throughout this book. For example, the box on the next page depicts the location of the beginning and end of the single Wilderness Waterway section we have labeled 1/U. (Sections in this guidebook are numbered 1–21 for the north-to-south route and lettered A–U for the south-to-north route, and all GPS coordinates are presented in the degree–decimal minute format.)

For a complete list of the GPS waypoints for the Wilderness Waterway, see Appendix 7, Everglades Wilderness Waterway GPS Coordinates.

The latitude and longitude grid system is likely quite familiar to you, but here is a refresher, pertinent to visualizing the GPS coordinates.

Imaginary lines of latitude—called parallels and approximately 69 miles apart from each other—run horizontally around the globe. Each parallel is indicated by degrees from the equator (established to be 0°): up to 90°N at the North Pole, and down to 90°S at the South Pole.

Imaginary lines of longitude—called meridians—run perpendicular to latitude lines. Longitude lines are likewise indicated by degrees: starting from 0° at the Prime Meridian in Greenwich, England, they continue to the east and west until they meet 180° later at the International Date Line in the Pacific Ocean. At the equator, longitude lines also are approximately 69 miles apart, but that distance narrows as the meridians converge toward the North and South poles.

To convert GPS coordinates given in degrees, minutes, and seconds to the format shown in the box below—degrees–decimal minutes, simply divide the seconds by 60.

For more on GPS technology, visit usgs.gov.

GPS Coordinates

SECTION 1/U: EVERGLADES CITY (GULF COAST VISITOR CENTER)/CHOKOLOSKEE ISLAND (SOUTH END)

Gulf Coast Visitor Center: N25° 50.730’ W81° 23.234’

Chokoloskee Island: N25° 48.537’ W81° 21.442’

CHARTS & USGS QUADRANGLES

At Everglades visitor centers, you can get maps for a few of the popular routes, such as Sandfly Island in the north and Nine Mile Pond and Hells Bay Canoe Trail in the south. Otherwise, for most of the paddles described in this book, navigational charts are essential. (See “Navigation”, and resources for buying the charts in Appendix 2, Launch Sites, and Appendix 5, Internet Sources.)

When you paddle interior routes not covered by nautical charts, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) 7.5-minute quadrangles (usgs.gov/pub) are useful. We list the quads in the overview information for each of those routes.

SHUTTLE DIRECTIONS

The Wilderness Waterway thru-paddle section of this guidebook includes shuttle information. Outfitters offering shuttle service are listed in Appendix 4, Resource Overview. All other paddles described in this guidebook start and end at the same location, so shuttles are not necessary.

PARKING & SECURING YOUR VEHICLE

When launching from Gulf Coast Visitor Center in the north or from Flamingo Visitor Center in the south, you may leave your car in the parking areas by the launch site. If you plan to paddle one of the canoe trails off the main park road in the southern section of the park, you will find a small parking area near your put-in. Either way, secure your valuables and lock your car.

you make backcountry campsite reservations, you will need to provide your vehicle license plate number, but there is no charge for use of the National Park Service (NPS) parking areas. (Note: It is understood that your car may be parked for more than a week if you paddle the entire Wilderness Waterway.)

PADDLING CONDITIONS

This section provides an overview of what to expect and plan for when you undertake your Everglades adventure.

MEAN WATER TEMPERATURES BY MONTH

Typically, water temperature is not a big issue for Everglades paddlers (though it is for fishermen). However, it is good to know that the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) site nodc.noaa.gov/dsdt shows water-temperature fluctuations for the region throughout the seasons. In July and August, the water temperature can reach into the high 80s; when a cold front comes through in the winter, the temperature can drop to the low 60s. To find current water-temperature data, you can access wunderground.com/MAR/GM/676 or marine.rutgers.edu/cool/sat_data.

GAUGING WATER LEVELS

The water-monitoring stations that you pass as you paddle in the Everglades measure water conditions such as temperature, flow, salinity, and water quality. This information is sent via satellite to the USGS. Its website waterdata.usgs.gov/nwis/rt traces the twice-daily rise and fall of water level and salinity, clearly showing how waterways in the Everglades are influenced by tides.

In addition to the daily tidal changes in water level, the yearly cycles of the rainy season (April–October) and dry season (November–March) affect many of your trips through the Everglades. In the dry season, there is a foot less water in the entire system than in the rainy season. A dry-season low tide may cause some routes to be impassable and make some chickees (sleeping platforms) inaccessible. Still, many of the routes in this guidebook are navigable in both wet and dry seasons. If a route or campsite might be difficult or impossible to access in dry conditions, we make note of this. But we suggest that you always inquire about current conditions at the visitor center.

The National Park Service (NPS) is the best source for current information about water levels on particular routes or campsites. For conditions at the north end of the park, call the Gulf Coast Visitor Center at (239) 695-3311; for the south end of the park, call the Flamingo Visitor Center at (239) 695-2945.

MIND THE TIDES

Keep in mind that one moderate low tide is generally followed by a high tide and then a more extensive low tide. But your awareness of the tides is more important in some areas than others. (See “Navigation”.) When paddling routes closely connected to the Gulf of Mexico, tide information is essential. Before leaving home, always download a tide chart (see saltwatertides.com), or ask for a tide chart at the visitor center. Paddling against the tide can double the time and effort required for some trips, so in the overview information that introduces each paddle in this book, we indicate the routes where it is particularly important to check tide tables.

A WORD ABOUT BOATING SKILLS

For safety’s sake, know your abilities on the water. If you are a beginner, choose day trips from the park’s north or south routes, or one-nighters on the Wilderness Waterway, before attempting to paddle longer segments of the Waterway. Trails such as Nine Mile Pond or the Buttonwood Canal minimize the dangers of wind and waves, while at the same time exposing you to the richness of Everglades bird life and vegetation. Kayakers and canoeists with more experience in paddling and navigation might choose longer trips through the rivers and bays in the Glades. Veteran paddlers can tackle the full Wilderness Waterway experience.

WATERWAY HAZARDS & SAFETY

While the Everglades may seem forbidding to absolute beginners, novices can enjoy some of the routes described in this guidebook. For all the pleasures, there are risks to consider when you head out onto any body of water, and paddling the Everglades is no exception. You may encounter waves caused by windy conditions in the bays and the Gulf of Mexico; strong tidal flow in rivers close to the Gulf; shallow water with exposed oyster beds, seagrass meadows, and mudflats; and mangrove tangles in narrow passages.

Paddlers may face heavy powerboat traffic on some routes, especially in high season. In every season in this part of the country, there is the risk of sunburn and heatstroke. Summer brings volatile thunderstorms, and winter introduces the chance of hypothermia. We highlight particular hazards of the routes in the introductory material for each route and give more detailed safety information in Parts One and Four respectively.

EMERGENCY RESCUE

Everglades paddlers often travel in remote areas, especially if you follow the entire Wilderness Waterway. While isolation adds to the beauty and appeal of the Everglades, there are no roadways where you will be paddling. Thus, any rescue along the routes covered in this guidebook will be by boat or helicopter.

If you find yourself in an emergency situation, stay with your boat and, if possible, remain near a marker or a campsite. Most of the Everglades National Park paddling area does not have cell phone coverage. For the full Waterway trip, we recommend carrying a marine radio, both for weather reports and to call for help in emergencies. The U.S. Coast Guard monitors channel 16, and powerboaters are required to keep their radios on and tuned to channel 16 to report emergency calls coming over the radio. Some paddlers may want to invest in or rent a satellite phone or a personal locator beacon, known as a PLB.

Still, never depend on electronic equipment alone. Trip planning and preparation, maps, a compass, and navigation skills should always be a part of paddling in this water world. Be sure to monitor weather reports in advance and check at the visitor center for seasonal conditions. Always carry more water than you think you will need, as well as extra food, emergency supplies, and first-aid equipment.

When paddling the Waterway or any of the overnight routes in this guidebook, you must make campsite reservations in person at one of the visitor centers within 24 hours before your launch, but you will not be required to check out when you complete the trip. Thus, prior to launching, be sure to let someone know your itinerary and give that person the park’s emergency number: (305) 242-7740.

For more information on safety and for more on equipment. Also see Appendix 1, Checklist.

WEATHER BY SEASON

Generally, Florida’s sunshine and warm temperatures make it an ideal destination for year-round paddling, as long as seasonal conditions are taken into account. Save the full Wilderness Waterway trip for fall, winter, or spring to avoid thunderstorms, extreme heat, and myriad insects. In the summertime, explore breezy, beautiful Chokoloskee Bay, do the serene Hurddles Creek Loop, or head out toward the Gulf of Mexico or Florida Bay, where the wind can blow the bugs away. Regardless of season, take along plenty of sunscreen, insect repellent, and water.

Winter

The region’s dry winter season—with clear skies, lower temperatures, and fewer mosquitoes and biting flies—is the most popular time for paddling. Temperatures average a daily high in the upper 70s and lows in the upper 50s. Monthly precipitation averages below 2 inches. But be aware that cold fronts may come through, dropping temperatures into the 30s and 40s. Cold fronts also can bring north winds that sweep water out of small bays, making some routes and campsites difficult to access. Be sure to check at the visitor centers for up-to-the-minute weather conditions.

Spring

The moderate temperatures and low rainfall of an Everglades spring begin in February and run into May. Spring highs average in the 80s in the daytime, 60s at night. Rainfall averages around 2 inches, increasing to 5 inches as the rainy season begins. A disadvantage of springtime paddling is that it comes at the end of the dry season. Water levels may still be low, creating more extensive mudflats and exposed oyster beds in tidal areas and making some interior routes too shallow to paddle.

Summer

This is the rainy season, with higher water levels caused by daily afternoon thunderstorms and the occasional tropical storm or hurricane. Rainfall averages for the summer range from just below 5 inches in July to more than 7.5 inches in August. Average temperatures run from the high 80s and low 90s in the daytime to the mid-70s at night. Mosquitoes and biting flies are much more of a nuisance this time of year, so be sure to protect yourself with insect repellent and/or bug suits. On the positive side, summertime paddling on short routes brings great opportunities for wildlife viewing and for a quiet, uncrowded experience. (See Part Four, Summer Paddling.)

Fall

In October and November, the extreme heat of summer is over, and the threat of afternoon thunderstorms has receded. Fall temperatures may hit the 80s in the daytime but drop to the 60s and 70s at night. Fall rainfall averages 4.25 inches in October, decreasing to 2.5 inches in November as you move into the dry season. And because rains have been falling for several months, there’s more water in the system. Paddling is lovely. But watch weather reports for afternoon thunderstorms or approaching tropical storms.

WILDLIFE

Birds

We present the topic of Everglades birds within the broader context of the Everglades ecology and environment.

Insects

These invertebrates are the smallest and least appreciated of the wildlife you will encounter in the Everglades. The most bothersome are mosquitoes, known as “swamp angels”; no-see-ums, also called sand flies; and yellow flies, often referred to as deer flies. At certain times of the year and in some locations, biting insects can be fierce, so bring plenty of insect repellent and be sure to have a tent with fine-mesh netting. Carry some topical Benadryl or other remedy to soothe your itches after the inevitable bites. (For additional tips on dealing with nuisance insects, “Insects”.)

You also may hear the buzz of black-and-yellow mud daubers, which are nonaggressive wasps that build tubular mud nests under chickee roofs. Less frequently encountered are paper wasps, whose nests may be found hanging from branches over narrow passages. Although these wasps are not aggressive either, take care not to knock the nest with your kayak paddle. They will defend their nest from attack.

But don’t forget to notice the charms of smaller wildlife. You may feel more welcoming toward other insects—especially the beautiful ones without stingers. We marvel at the butterflies that flutter around our boat far out on open water; at the large, patterned moths at the chickees; and at the dragonflies in the mangroves when we tie up for lunch or wait out a storm.

Mammals

There is little chance of seeing a bear or Florida panther in the Everglades any longer, although you may spot a bobcat. We have seen bats at several campsites and know there are opossums in the Everglades because Darwin’s Place is on Opossum Key. But we have never seen opossums, bears, or panthers.

Raccoons, however, are a different story. As smart and aggressive in the Everglades as they are elsewhere, raccoons will try to steal your food at ground sites, so be sure to secure your food supply with bungee cords. And because freshwater is scarce in the Glades, they may also try to chew their way into your water containers. Although we have never had problems with rats, the park rangers have related stories of these critters being pesky at campsites too. As long as you protect your supplies, however, seeing raccoons and rats can be part of the adventure.

You might catch a glimpse of deer, particularly if you stay at Highland Beach. Although deer are generally upland creatures, even antlered deer can penetrate the thick tangle of mangrove forests.

But the most frequent mammals you will encounter on your paddles are Atlantic bottlenose dolphins. Although they are saltwater mammals, dolphins travel upriver in search of prey and can be observed splashing in bays or herding fish onto riverbanks. They are curious and sometimes tilt their bodies to watch you with an inquisitive eye.

Consider yourself fortunate if you encounter another marine mammal, the manatee. Not carnivorous like dolphins, manatees feed on seagrass and can be spotted at the mouths of Everglades rivers or in the Flamingo marina. Look for manatee “footprints,” the flat circles on the surface of the water that indicate a manatee may be paddling by.

Oysters

This may surprise you, but one animal of the Everglades that has the potential to cause harm is the oyster. This marine invertebrate starts its life in larval form floating around in salt water until it anchors itself with many other oyster larvae on a shallow spit of land. There it makes its living filtering food from the incoming tide. The danger lies in the fact that oyster shells are razor-sharp and some oysters carry disease—Vibrio vulnificus or Vibrio parahaemolyticus. To avoid cuts, we advise you to always wear water shoes while paddling—and do not step out of your boat without those shoes securely on your feet.

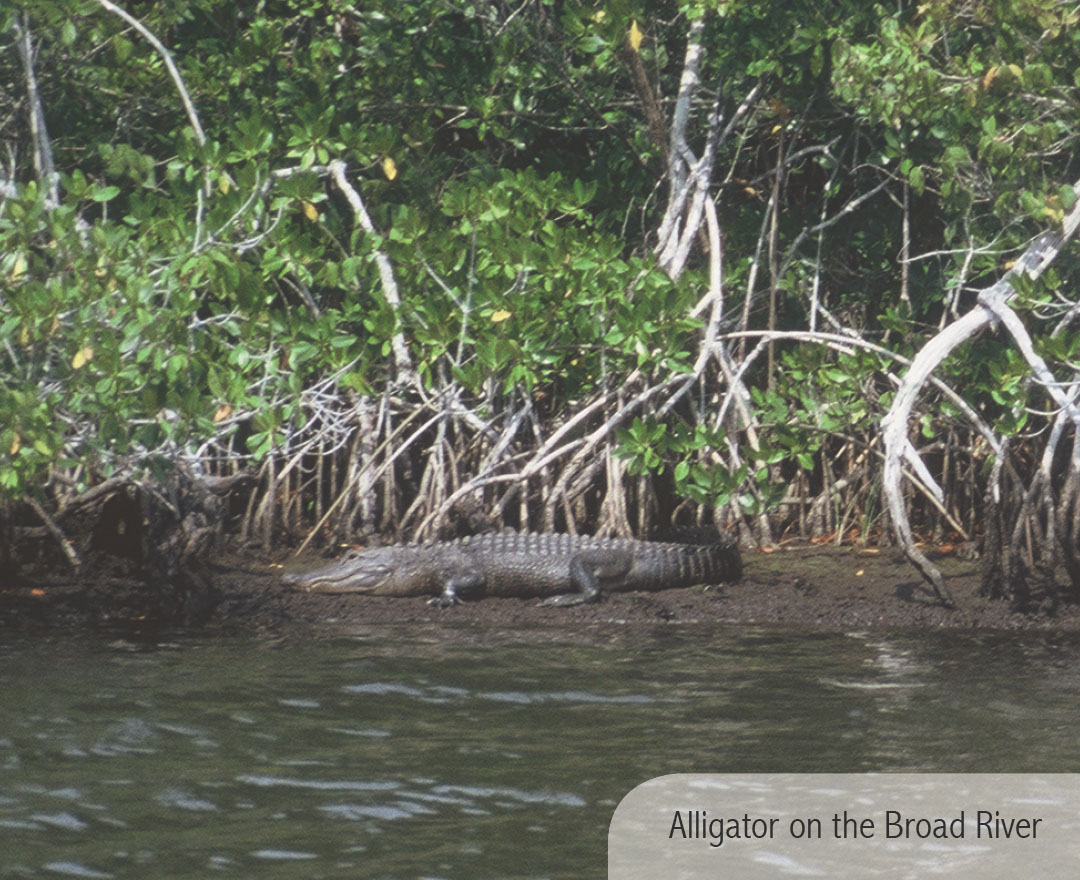

Reptiles

Many people who venture into the Everglades for the first time worry about snakes and alligators. We’ve seen only two snakes on the Waterway and they were small and nonvenomous. We’re sure there must be some snakes out there on the ground sites, but snakes tend to want to keep away from humans.

Widespread press coverage of nonnative pythons, introduced into the park by pet-owner release, may raise questions for some. These pythons are reproducing, and the population of small mammals, a food source, seems to be diminishing. Park biologists are studying these reptiles, and they ask that anyone who sees a python notify them of the location.

As you paddle, you may see alligators on the banks along the routes, but these animals are shy and will slide into the water as you pass. The only cases where we have observed this not to be the case is when an alligator hangs around a campsite because it has become habituated to getting scraps from campers and fishermen. When fed by humans, alligators can become dangerous. So do not dump food scraps, even small ones, into the water.

American crocodiles also have a presence in the Glades. They are an endangered species, and you will be fortunate if you see one, with its pointed snout and toothy grin. Whereas alligators prefer fresh or brackish water, American crocodiles require salt or brackish water. Like the alligator, the American crocodile is a nonthreatening presence in its natural habitat. Enjoy these creatures respectfully.

For more on individual members of the animal kingdom, Part Six, Everglades Flora, Fauna, People, & Places.

CAMPING

Two front-country, drive-in campgrounds sit at the southeastern entrance to the park near Homestead. Long Pine Key Campground, which does not accept reservations, is 6 miles southwest of the Ernest F. Coe Visitor Center. Flamingo Campground, which does take reservations, is on Florida Bay, near the Flamingo Visitor Center at the end of the 38-mile park road. (Additional lodging and campgrounds are available near the northern and southern ends of Everglades National Park and are listed in Appendix 4, Resource Overview, on page 278.)

You must make reservations with the NPS to camp at any of the three types of backcountry sites available within the park and briefly described here. For detailed information about each overnight locale referenced in this book, please see Part Five, The Campsites. Also visit nps.gov/ever.

Chickees

Constructed on pilings over water, chickees are open-sided, wooden platforms with a roof. See more about chickees in “Camping on Water, Land, & Shore.”

Ground Sites

Ground sites consist of small, cleared areas primarily on old Calusa shell mounds. Most ground sites have picnic tables and portable toilets, and some have docks.

Beach Sites

Beach sites are just what their name suggests—campsites directly on the sandy shores of the Gulf of Mexico or on keys in Florida Bay.

YOUR RIGHTS & RESPONSIBILITIES

The paddles described in this book are all within Everglades National Park, whose waters have been preserved from development and commercial use by the NPS. As members of the public, we are invited to enter the Glades thoughtfully and responsibly. An entrance fee is required for access at the south end (Homestead) and, except in the summertime, you must also pay a small fee for a permit if you intend to camp.

Rules and regulations are printed on Everglades camping permits and in the Wilderness Trip Planner brochure available at the visitor centers or online at nps.gov/ever. When you purchase permits, a ranger will go over the requirements. Examples of regulations include:

| ► | Florida Bay keys are closed for boat landings (except for Bradley Key and the keys designated as campsites). |

| ► | to some islands and bays is limited because of protected bird rookeries. |

| ► | Fires are not permitted except on beach sites. |

| ► | No ash-producing fuel, such as charcoal or wood, may be used on chickees or ground sites. |

| ► | Leave no trace. Whatever you take with you, you must pack out. |

| ► | Urinate directly into the water; for human waste, if there is no privy, bury the matter 6 inches deep in the ground. |

The areas immediately around Everglades City and Chokoloskee Island are not themselves part of Everglades National Park. When visiting or launching from these sites, please respect landowners’ rights. Be aware, as well, that many of the outfitters and marina operators in this area are descendants of original pioneer families. They are knowledgeable and proud of where they live, and they will be helpful to and appreciative of those who respect the history and the ecological integrity of their home. Many of the residents are committed to offering ecotourism opportunities. We encourage you to get to know them if you have questions or need guides.

WATERWAY ETIQUETTE

Here are a few reminders to enhance everyone’s pleasure:

| ► | Stay to the side of channels and, if motorboaters slow to idle speed, stop paddling until they pass. To avoid being swamped when powerboats pass without slowing, turn your bow into the wake. |

| ► | For group paddles, plan your choice of campsites carefully. Only one tent will fit on a single chickee platform (double chickees accommodate two), and ground sites as well as some beach sites are small. For the maximum number of people and parties allowed at each location, see Part Five, The Campsites. And remember, unless you encounter dangerous conditions or emergency situations, do not stay at sites you have not reserved. |

| ► | When camping in proximity to others, be respectful of their needs for a quiet and peaceful wilderness experience. |

ECOLOGY & ENVIRONMENT

Diverse waters mingle in the Everglades. The Wilderness Waterway and the paddling areas to the north and south of it are fed by three different watersheds, each of which is called a slough (pronounced “slew”). Here is a brief orientation:

When you are deep in wilderness in the central areas of the Waterway, you will be paddling in waters from the Shark River Slough as it travels to the Gulf of Mexico.

When you travel routes in the Chokoloskee Bay area, you are paddling in water of the Fakahatchee Slough, which has passed through Big Cypress Swamp.

If you paddle one of the canoe trails off the park road at the south end of Everglades National Park, you will be traveling on water from Taylor Slough.

And if you venture out into Florida Bay, you leave the freshwater flow of the sloughs behind and enter an open marine environment spreading from the tip of peninsular Florida to the Florida Keys.

THIS “RIVER OF GRASS”

The definition of the word Everglades is unknown, although the term may have its roots in the Middle English word glad, meaning “bright, shining.” The venerable author, environmentalist, and Everglades champion Marjorie Stoneman Douglas (1890–1998) aptly called her beloved wetlands and her 1947 classic work, The Everglades: River of Grass. In that book (a 60th-anniversary edition was published in 2007), she noted that the term Everglades first appeared on an 1823 map.

Seminoles called it Pa-hay-okee, meaning “grassy water.” In his account of his 1896–97 trip, Across the Everglades, Hugh Willoughby described it as “a sea of apparently pathless grass.” Naturalist author Ted Levin titled his Everglades book Liquid Land.

Regardless of the word’s source, these “glad” Glades, this bright, shining place, consists of 1,508,571 acres that stretch diagonally from the southern Gulf Coast of Florida into Florida Bay. The region’s aesthetic and ecological value has earned it three of our planet’s most prominent designations: International Biosphere Reserve, a World Heritage Site, and a Wetland of International Significance.

All appellations aside, the place is surprising. Visitors often expect to see swamps and cypress trees and are awed by the sawgrass prairies extending across a flat landscape to the horizon. In fact, the Everglades harbors five distinct ecosystems:

| ► | sawgrass prairie |

| ► | rock pineland |

| ► | hardwood hammock |

| ► | dwarf cypress forest |

| ► | mangrove forest |

While most of the paddling areas are in the mangroves, if you enter the park on the Homestead side and drive the 38 miles of the main park road to Flamingo, you will pass through all five ecosystems. In that short distance, you will travel from freshwater sawgrass through brackish habitats to saline estuaries characterized by mangroves.

With its mosaic of habitats, a unique combination of geography, water flow, and weather, the Everglades presents an ideal environment for a rich diversity of both plants and animals. Poised at both the southern limit of the temperate zone and the northern limit for many tropical species, temperate and tropical species blend here in ways that are rare in the world. It is this richness of biological diversity that earned the Everglades its status as a national park. This was the first park to be preserved not for its gigantic or geological wonders but for its biological uniqueness and the subtleties of its cycles.

WADING BIRDS

Because these flying creatures are such an encompassing part of Everglades environment and history, as well as an indicator for its future, we include them in this discussion rather than in the previous “Wildlife” section.

In the wondrous diversity of the Everglades, wading birds are among the features people most admire and enjoy. Wood storks, white ibis, glossy ibis, and roseate spoonbills soar over the park’s wetlands. Herons and egrets of all sorts—great blue, little blue, green, reddish, and tricolored herons and great and snowy egrets—wade and wait along narrow streams, in shallow seagrass meadows, and on low-tide mudflats. But there are not as many as there once were.

Nothing was more striking at one time than the vast numbers of wading birds that fed and multiplied in the Everglades. Audubon wardens in the 1930s estimated a population of 250,000 wading birds, primarily white ibis, along with roseate spoonbills, egrets, herons, and wood storks. But that population was small compared to the sightings of earlier naturalists. They wrote of flocks that blackened the sky. For decades, dating back into the early 1800s, the beauty of these birds’ nuptial plumage charmed not only potential mates and Florida naturalists but also the eye of big-city fashion designers who sought to adorn ladies’ hats with feathers. There was money to be made as a plumer, with the price of feathers rising to $32 an ounce (which would equal almost $800 an ounce today).

As the feather trend raged, the population of wading birds was being decimated, with hunters often shooting up an entire rookery, killing hundreds or even thousands of adult birds on the nest, leaving eggs and chicks abandoned. Finally, in 1901 the state of Florida passed Chapter 4357, a bird protection act that opened the way for game wardens to patrol the rookeries in the Everglades. Contracted by the American Ornithologists’ Union (which later became the Audubon Society), Guy Bradley was the first of these wardens. He was killed in 1905 when he went after suspected plume hunters in the Oyster Keys of Florida Bay. Bradley was the first of several wardens who would lose their lives in the line of duty. (For more on Guy Bradley, see the Johnson Key overnight paddle description.)

Ultimately, it was fashionable women themselves who came to the rescue of the birds. For a while they had believed what they were told, that the birds shed their feathers naturally. When the truth came to light, small groups of women banded together to boycott and to urge others to boycott hats that were adorned with feathers. As fashion changed and demand dropped, so did the price paid to plumers for feathers, and the trade ceased to be profitable.

Since then, bird populations have recovered somewhat, but issues related to water quality, quantity, and timing have interfered with a fuller recovery. For decades, discussions of how to preserve what remains of the Glades, its birds, and other biological wonders have circled, repeated, and droned on, as funds for restoration have been allocated and then never delivered and as life-giving water dynamics have deteriorated.

Sometimes, for example, large quantities of water have been unnaturally released into the park from dikes built to protect agricultural lands and developments. Such a release of water, at a time when water levels in the park would normally be low, can have devastating effects on wildlife, including the endangered wood stork, the only true stork native to North America. These birds are touch feeders: they locate their prey by moving their curved beaks in shallow water until the beak bumps into something, at which point it opens and snaps up whatever fish or crustacean it has bumped. During the nesting season, a wood stork needs to have several hundred pounds of nourishment, an ounce or two at a time, bump into its beak in order to have sufficient food for itself and its young. Shallow water, where creatures are concentrated, is essential. If water comes roaring in from the north during the wood stork’s nesting time, artificially raising water levels and dispersing aquatic animals, the stork cannot feed its young, and a whole nesting season, for a bird already endangered, can be lost. Water timing is essential. The dry season is as life-supporting as the wet season.

For more on the prevalent bird species you are apt to observe here, see Part Six, Everglades Flora, Fauna, People, & Places.

EVERGLADES UNDER THREAT

We will never see what the original vast expanse of sawgrass must have been like. Agriculture, urban expansion, and dredging have forever altered natural Florida. The full Everglades system, stretching from just south of Orlando to Florida Bay, is now beyond the possibility of restoration. Everglades National Park protects only about one-fifth of the original Everglades, and even this fraction is endangered.

The Everglades formed approximately 5,000 years ago when rain and rising sea levels flooded South Florida. Natural barriers formed by the Atlantic Coastal Ridge on the east and, to a lesser extent, Big Cypress Swamp on the west held these waters in a shallow trough, forcing them to make a journey south from Lake Okeechobee to the tip of the Florida peninsula. In this flow, upland plant species died, and marsh plants such as Jamaica swamp sawgrass (Cladium jamaicense) thrived, becoming the primary vegetation of the “River of Grass.”

Waters of these historical Everglades originated in central Florida in the Kissimmee River. Fed by drenching summer rains, river waters flowed slowly southward toward the shallow, southward-tilting bowl of Lake Okeechobee. Spilling over the edges of Okeechobee, the wide, shallow flow continued (“an excruciatingly slow descent,” according to author Archie Carr) in two directions—southwest to the Gulf of Mexico and south into Florida Bay.

But in 1904, a time when most of South Florida was viewed as useless swampland, Governor Napoleon Bonaparte Broward campaigned under the slogan “Drain the Everglades,” and the land boom began. The areas south of Lake Okeechobee buzzed and clattered with activity—dredging canals to drain the land and irrigate fields for sugarcane, vegetable farming, and ranching industries; building roads; and constructing housing developments. The Everglades, whose area once totaled 6,000 square miles, began to dry up. Canals and construction interrupted the flow and threatened ecosystems that would become increasingly dependent upon rainfall as a source of water.

Although the dominant cultural idea of the time was to drain and develop, some people recognized that a rich resource was being lost. In 1916 the Florida Federation of Women’s Clubs lobbied to preserve a small portion of land in the Glades, a hammock called Royal Palm. Then, along with similar groups and noteworthy individuals such as Ernest F. Coe and Marjory Stoneman Douglas, they labored over the next 30 years promoting the creation of a national park. In 1947, with neither spectacular mountain scenery nor dramatic waterfalls and canyons, Everglades National Park became the first national park established to protect plants and animals and their unique habitat. But protection hasn’t been easy because the park is affected by what happens outside its boundaries. Water that does get through to the Glades from the north, either naturally or by human decision, is often polluted by runoff.

But all of the news is not bad. One major, long-awaited project has broken ground—a stretch of bridge to replace a section of the Tamiami Trail (FL 41), a road that has, in effect, been damming the flow of water into the Everglades. This bridge is hailed as an essential element in assuring that the ecosystems of the park can survive.

Further Information

For information and updates on threats to the Everglades and current preservation and restoration efforts, including how you can help, consult the websites of Friends of the Everglades (everglades.org), an organization founded in 1969 by Marjory Stoneman Douglas, and Audubon of Florida (fl.audubon.org).