PROGRESS OF THE COMBINED OPERATIONS AGAINST PORT ARTHUR, AND ADMIRAL BEZOBRAZOV’S SECOND DIVERSION.

[Charts J, K 2. Map D.]

THE month which succeeded the sortie of June 23rd was a period singularly devoid of incident and yet, for the Japanese at least, it was perhaps the most critical of the war. It is just one of those intervals which history is inclined to slur over as unworthy of attention, although for technical purposes they merit close study. Such colourless periods have occupied the greater part of naval wars and upon their right treatment most wars have turned.

Barren as was Admiral Vitgeft’s effort of any positive result, it meant a profound change in the whole aspect of the war. Though superficially it seemed an ignominous failure for the Russians, it marked, in fact, a serious set-back for the Japanese, and with no illusions they frankly recognised a strategical reverse. Their war plan, as it then stood, turned on an immediate concentric advance upon Liau-yang and a blow at the Russian concentration zone in the week or ten days they had in hand before the rains set in. As we have seen, the orders for the preliminary forward movements had already been given; they were on the point of being executed on all three lines of advance, when on June 24th, the day after the sortie, the whole movement was stopped. It was not merely that the sortie, by preventing the formation of the supply base at Gobo, had made it impossible for General Oku to advance; the whole military plan had been based on the assumption that the fleet had obtained such a preponderance in the Yellow Sea that there was no serious danger of the army communications being interrupted. The events of June 23rd had demonstrated that no such preponderance existed. Not only was it clear for the first time that the blocking operations had entirely failed to seal the port but, to the surprise of the Japanese, the Russian Squadron had succeeded in finishing its repairs and to all appearance had completely recovered from the effects of the first blow. The situation therefore was changed to its foundations, and if the restored squadron were handled with anything like the dash of the Vladivostok cruisers, the supply of the four Japanese armies was highly precarious.

At any rate the risk was more than the Imperial Staff could face. In the evening of the 24th General Kawamura, who was on the point of moving forward on the Ta-ku-shan line to stretch out his left to the Second Army, received from Tokyo the following telegram:—“The fact has been proved that the Russian fleet is able to come out of Port Arthur. The transport by sea of the supplies, which will be required by the combined Manchurian armies after their arrival at Liau-yang, is therefore rendered uncertain, nor is it advisable for the Second Army to advance further north than Kaiping for the present. The battle of Liau-yang which we expected to fight before the rains will now be postponed till after them. Arrange your operations accordingly,” A similar order was sent to General Kuroki directing him “to make his dispositions in accordance with the new plan”; while as for General Oku his position was even worse than was realised at Tokyo. Until Dalny was clear of mines and locomotives could be brought from Japan to work the railway his progress even up to Kaiping depended, as we have seen, on an advanced supply base being established by the fleet in the Gulf of Liau-tung and nourished from the sea; and since the sortie of the Russians it was obvious that Admiral Togo could not undertake any operations on the far side of Port Arthur. The dispersal they would entail was not to be thought of. Consequently General Oku had to inform General Kawamura that he could not advance in time with him. Though he was but 13 miles north of Telissu his land transport was insufficient for the daily needs of his army; an accumulation of stores on his line of advance was out of the question; and consequently he would not be able to move on Kaiping for some time.1

Possibly the Japanese Staff was unduly nervous about the oversea communications, but it must be remembered the state of public feeling was such that the Government could not face the prospect of a repetition of such regrettable incidents as had recently occurred in the Straits of Tsushima. Even had they been willing to take the risk still it would have been useless and even vicious for the First and Fourth Armies to advance till the Second was able to move, and for the present without naval assistance General Oku could not stir.

Of such assistance there could be no immediate hope. It was not only that the fleet must be kept closely concentrated in view of the renewed vitality of the enemy; there were other reasons which were inherent in the sound, if cautious, plan which the Imperial Staff had now adopted. Stated theoretically the position was this. The defensive basis of the campaign had broken down—that is, the control of the Yellow Sea on which the offensive operations of the army depended was no longer secure. To restore the situation, the defensive basis must be restored. Not till then could the land forces recover their freedom of action and offensive impetus. Upon this work then the whole effort of the fleet must be concentrated, since by the Japanese war plan the fleet was the defensive force, and until it was done it was unsound to deflect any of Admiral Togo’s all too little strength in furthering the main offensive operations.

The key of the situation lay in Port Arthur, and so far as anyone could see the situation could not be restored until the place had fallen or the fleet it held had been destroyed. For this they had to look to General Nogi and the Third Army, and the fleet must devote itself to assisting and supplementing his operations. Every unit would be required. For it meant not only an increased rigour of blockade by mining and greater cruiser vigilance to prevent the possibility of escape, but also a considerable inshore force to give tactical support to the troops.

Not a day was lost in getting to work. General Nogi, whose position extended from the inlet west of Dalny across the peninsula to the western extremity of Society Bay, decided to push back the forces on his left front and seize the high ground which they occupied, known as Chien-shan. It was of vital importance, for it dominated not only his own position, but also the enemy’s ground as far as Port Arthur. Simultaneously, as two sections of the Dalny area had been cleared of mines, Admiral Togo was able to modify the disposition of the fleet in a way that set free a division of his force for the naval support required. On June 25th Admiral Miura received orders that the landing place of the army transports was to be advanced to Dalny Bay. This liberated the Fifth Division which had been employed in protecting the original landing places in Yentoa Bay and made it available for patrol work. Its new station was Cap Island, which it now occupied in alternate sub-divisions, and thence covered the completion of the sweeping in Talien-hwan and the inshore operations on the left of the army. Admiral Hosoya was again given general charge not only of the new base, but also of the operations for supporting from the sea General Nogi’s intended attack.

The latter function presented almost insuperable difficulties. The Russians were believed to have mined the whole coast, and until systematic sweeping operations could be undertaken tactical co-operation with the Army could not be given effectively.2 Nevertheless, the General did not wait. He made his attack, and it was so successful that by the 26th he had not only captured Chien-shan, but had pushed his left four miles beyond Ping-tu-tau as far as Lao-tso-shan, where he was only about six miles from the eastern face of the fortress. The whole thing was done with little or no naval support. A few of the auxiliary gunboats did indeed get in and harass the Russian right, but the broken nature of the ground made their fire negligible. Still the moral effect on the troops was sufficient to cause the general to telephone for naval assistance. In response, Admiral Loschinski came out in the Novik with two gunboats and 13 destroyers, and in the last phase of the operations began a severe bombardment of the Japanese left; but a demonstration by Rear-Admiral Togo, whose turn of blockade duty it was, was enough to drive him back. Next day, in expectation that the Japanese would continue their advance, Admiral Loschinski was ordered out again, but as the enemy stood fast he remained all day in Ta-ho Bay, occasionally firing, and retired again in the evening.3

So bold an advance of the Japanese Army could only render more acute the most serious anxiety, which was that as the military pressure on Port Arthur increased the fleet would be forced to break away. A report of smoke rising from the harbour on the 26th was enough to bring Admiral Togo out, and that night the whole fleet kept guard at its intercepting stations. The battle division accompanied by a strong flotilla was halfway between Port Arthur and the Korean coast in a position which may be taken as the centre of the Yellow Sea. Between it and Shangtung was Admiral Dewa with the Third Division, while on the left was Rear-Admiral Togo, some 25 miles north-east of Chifu. The disposal was thus approximately on the quadrant of a circle whose centre was Dalny Bay with a radius of some 60 miles.4 At dawn they closed in to Round Island, and hearing all was quiet Admiral Togo withdrew to the Blonde Islands, where he lay fog-bound till the end of the month.

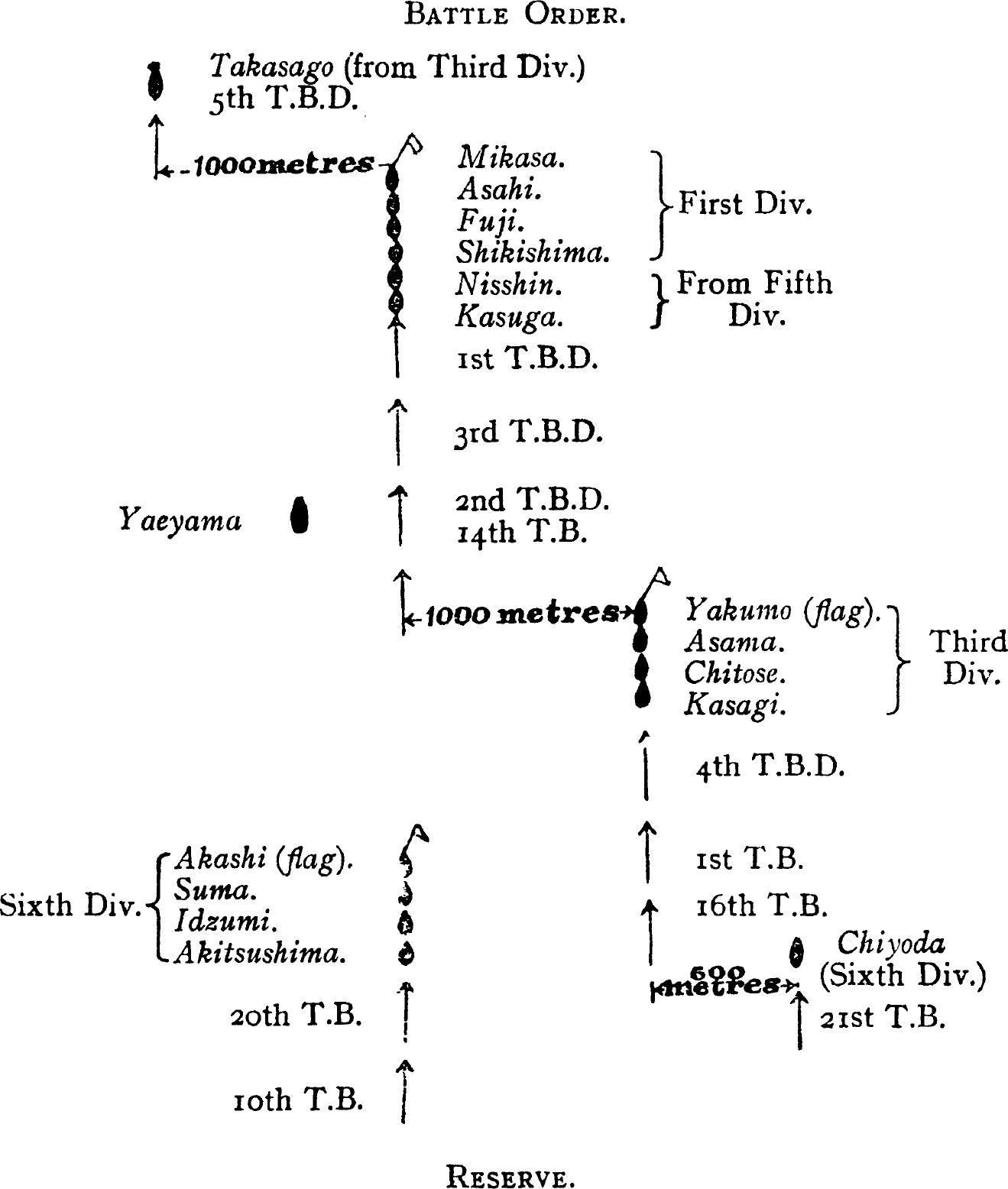

This period the Admiral employed in drawing up fresh battle instructions in view of the new situation. They were issued when he was able to return to the Elliot Islands base on July 2nd. His scheme was founded on the estimate that the enemy’s working strength was 5 battleships, 5 cruisers, and 13 destroyers, and that their speed when the Sevastopol was in company would not exceed 12 knots. “The tactics we must employ,” he wrote, “must be designed so that we may constantly take the offensive, utilising the superior speed of our battleships and the superior numbers of our destroyers and torpedo-boats.” The order of battle would be composed of the First, Third, and Sixth Divisions. The Fifth Division would act as a reserve. With the battle squadron would be a flotilla composed of four divisions of destroyers and eight of torpedo-boats; with the Reserve, three divisions of torpedo-boats. The battle formation was laid down in the accompanying diagram. It was to be “maintained to within 10,000 metres of the enemy, after which the separate divisions are to act as circumstances dictate.” Each section of the flotilla was to follow the division to which it was attached on the disengaged side. The Reserve was to keep out of action but within sight, and “if necessary” to come up and engage. In this arrangement, it will be observed, he seems to have been influenced by Nelson’s Trafalgar memorandum in that he kept the approach up to effective range in his own hand and left the conduct of the actual attack to his divisional commanders. For their general guidance he drew up the following instructions:—

“The First Division with the Nisshin and Kasuga from the Fifth Division are to be the main force. The chief duty of the Nisshin and Kasuga is to protect the flotillas, but if occasion offers they are to bring them up to attack the enemy’s line.”

Defence against torpedo attack was provided for by the Takasago of the Third and Chiyoda of the Sixth Division, the former leading a division of destroyers, the latter one of torpedo-boats. Disposed respectively in van and rear they were told off to “act independently against the Novik and the Russian destroyers, and to prevent them making torpedo attacks,” but they were also directed to “make feints at high speed against the enemy’s main body, so as to throw it into confusion.”

Fifth Division—Chinyen, Itsukushima (flag), Hashidate, Matsushima. Attached flotilla—2nd, 12th, and 6th T.B. Divisions.

The rest of the Third Division (Yakumo, Asama and Kasagi) was to act primarily against the enemy’s other cruisers but it was also “to co-operate with the First Division and attack the enemy’s rear as convenient,” and if occasion offered it might attack the Russian flotilla.

The main duty of the Sixth Division was to destroy the hostile flotilla and isolated ships, and so long as it did not obstruct the movements of the other two divisions it might bring up the flotilla when it saw a chance of attack.

The Yaeyama was to carry orders and pass signals.

Then follow the tactics to be employed. They were to be based as in his original memorandum on the T and L formations. “But when within 4,000 metres (4,400 yards),” he adds, and they can fire torpedoes at us, these will be avoided by a turn together towards the disengaged side, returning to single line ahead again when at appropriate range. When we turn the flotilla which will be on our disengaged side will also turn together.” Even when the formation he intended could not be taken up precisely, the First Division, he says, “will try to utilise its superior speed as in previous battles to press the van of the enemy’s line. When this occurs the Third Division will break off to starboard and vigorously attack their rear.”

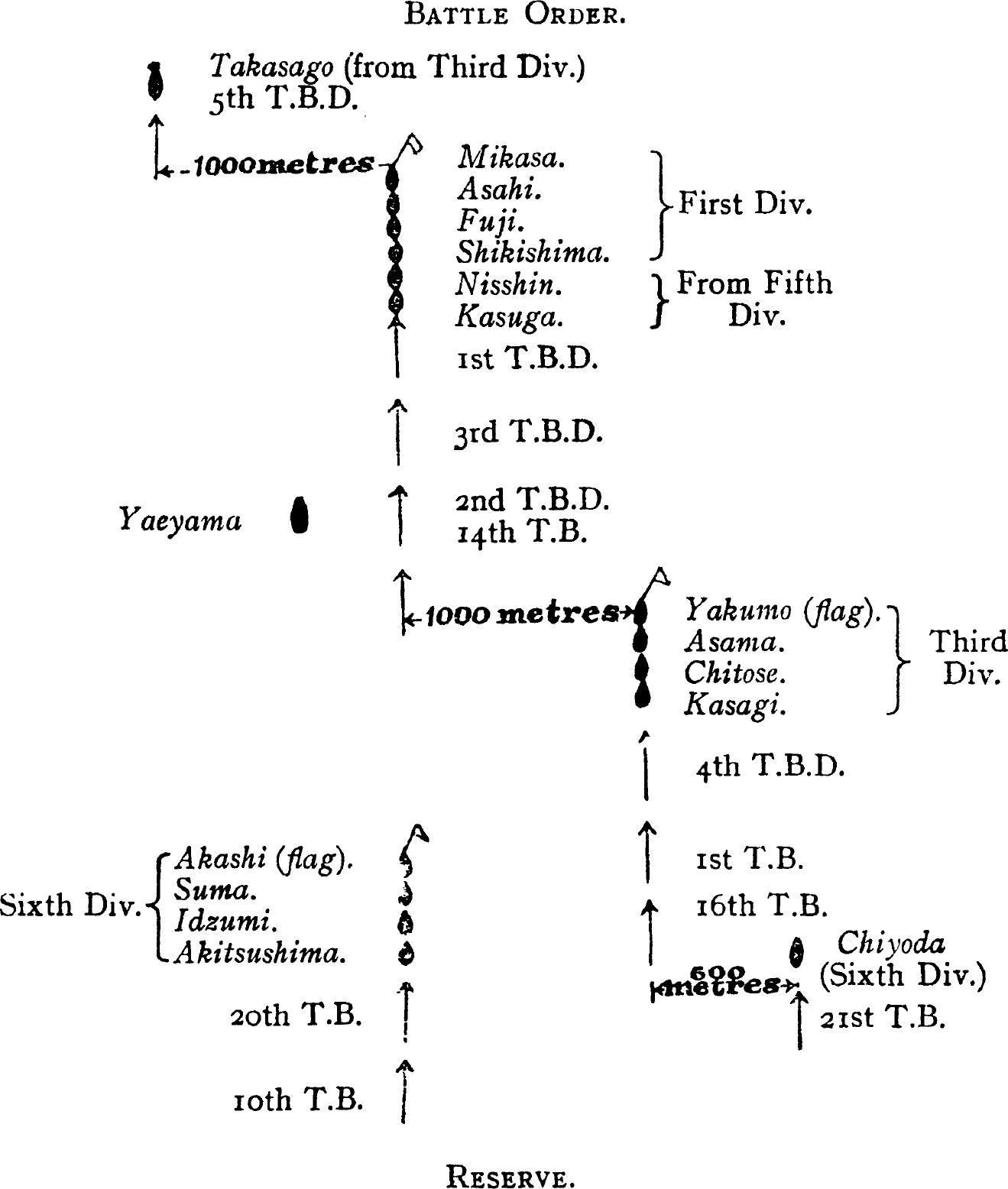

As to the use of the torpedo in action he adds—“Up to the present time practical experience has shown that the enemy’s fire on flotillas is almost entirely ineffective: the only hits they have made have been by shrapnel. It is, therefore, probable that a torpedo attack delivered even in broad daylight might well be successful. A moonlight night should be even more favourable to us. There should be no useless waiting for the moon to set [a remark obviously prompted by the behaviour of certain divisions during the recent attack]. I shall, therefore, in the future order torpedo attacks in the daytime, and all the flotillas must be fully prepared for them. The method to be followed is for two divisions to run up together, turn to port and starboard respectively and make a simultaneous attack,” as in the diagram opposite.5

This of course was a striking innovation marking significantly the modern tendency to throw into the battle any class of vessel which can possibly add to the weight of an attack, no matter what the specialisation of the type.

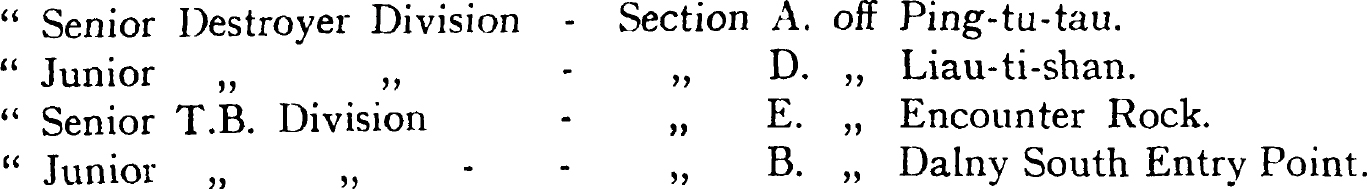

At the same time he revised the arrangements for securing contact. The watch he was keeping was still “open” in form with the bulk of the fleet massed at the Elliot Islands and one cruiser sub-division off the port as an in-shore or observation squadron supporting the flotilla patrols. It was known as “the sub-division on blockade duty.” By the new order it was to be relieved every three days instead of every two and at night it would retire from its day station (that is, Position P. four miles south of Encounter Rock) to Position H (22 miles N.E. of Shantung Promontory). The night flotilla patrols were carefully re-arranged to provide early notice of a sortie and their shelter and rest station was advanced to Odin Cove, just inside Talien-hwan.6

If the warning signal came in the hours of darkness the fleet would move from the Elliot Islands as follows:—

The Third Division and attached flotilla will steam S. 6° E. between position T (three miles S.W. of Chang-zu-do) and position 560 (60 miles west of Ross Island).

The First Division and attached flotilla will steam S. 16° E. between position T and position 241 (west of Ross Island).

The Nisshin, Kasuga and Yaeyama of the Fifth Division7 and the Sixth Division with attached flotilla will steam S. 11° E. between position T and position 418 (40 miles west of Ross Island).

Unless special orders are given the speed is to be battle speed. Course should be altered as convenient to the westward according to the time of the enemy’s emergence and their progress.

If the blockading squadron and flotillas lose sight of the enemy, they are to steam S. 46 E. from position P to position H; and from position H they will proceed on the track laid down for the Third Division.

If the enemy, although lost sight of, are thought to be still north of Shantung Promontory all ships will assemble at position 769 (25 miles east of Shantung Promontory.)”

The idea it will be seen was that as soon as he had reached position T. and was clear of the Elliot Islands he would begin to spread his fleet on three diverging courses with his fastest cruisers nearest the enemy and the battleships furthest away. On these courses he would proceed to occupy a line west from Ross Island unless contact were secured previously. If his information as to the position and speed of the enemy justified it, he would alter to the westward with a view of getting contact earlier. If the observation squadron lost touch and there was reason to believe the enemy had not passed the narrows he would occupy a line off Shantung Promontory.

If Admiral Togo considered such a disposition necessary to make sure of preventing the enemy’s escape it is easy to understand the nervousness of the Military Staff about their communications. The Ross Island position, which might have to be taken up, left practically the whole of the Yellow Sea open to the activities of the Russian squadron should it double back in the way Admiral Vitgeft had intended when he last came out.

The motive which determined the disposition is probably to be found in the consideration that if the enemy broke out at night they would be able to get too far south to be easily headed back and that a decisive battle would probably have to be fought. Such an action demanded the whole available force that could be assembled. Now at Ross Island the Commander-in-Chief would be in wireless touch with Admiral Kamimura through Hakko and he would thus have his whole battle strength concentrated at the decisive time and place.

That this was the master consideration seems clear from an order which he gave at this time to his colleague. On June 30th while he was still fog-bound at the Blonde Islands and was actually settling the new instructions, information had come that the Vladivostok cruisers were out again and had appeared before Gensan. He immediately stopped the movement of all transports and sent the news on to Admiral Kamimura with the caution that unless there was a good chance of closing with the Russians he was not to go far from his station, an order which seems to suggest that he did not approve of the way in which the Straits Squadron had been handled on the occasion of the last raid of the northern cruisers. In any case Admiral Kamimura was told to content himself with keeping a firm hold on the keys of the Straits, and to distribute his patrols so as to make sure his communications should be certain and quick. The inference is that he suspected the Vladivostok detachment might be bent on drawing Admiral Kamimura away from the strategical centre at the vital moment so as to defeat the concentration he was planning. Till the hour of battle came Admiral Kamimura’s function was strictly defensive—to keep control of the main line of communication—and he was to be held to it. In view of what occurred afterwards, this order has a peculiar importance.

The meaning of the appearance of the Russian cruisers off Gensan was precisely what Admiral Togo was anticipating. On hearing of the sortie of June 23rd the Viceroy telegraphed to the Commander-in-Chief at Vladivostok suggesting that he should endeavour to facilitate Admiral Vitgeft’s task by making a diversion on the Japanese line of communications. In pursuance of this suggestion, while the Russian headquarters were still without any news of the result of the sortie, Admiral Bezobrazov was ordered to sea and sailed on June 28th, two days before Admiral Vitgeft’s depressing report reached the Viceroy.8 The force entrusted to him comprised the three armoured cruisers and the auxiliary cruiser Lena, as parent ship to eight torpedo-boats, and his instructions were to take the flotilla down to Gensan and make a night attack on the port. The Lena would then escort the torpedo-boats back while Admiral Bezobrazov with his cruisers made a dash through the Straits for the neighbourhood of Quelpart. In the early hours of the 30th the attack on Gensan was made. Two small merchant vessels were found. Both were destroyed and the Japanese settlement bombarded, but the only material result was that one of the Russian torpedo-boats ran ashore and had to be blown up. The delay caused by the accident was even more serious, for the cruisers were not able to begin their move south till noon, too late to run the Straits in the night, and Admiral Kamimura had timely warning.

Early in the morning he heard from Tokyo of the torpedo-boat bombardment at Gensan and that three cruisers appeared to be in the offing. The moment was peculiarly inopportune. The last raid had taught the importance of getting early and certain intelligence of the movements of the northern cruisers, and for this purpose it had been decided to establish a new signal station on the Korean coast at Chukupen Bay,9 about half way between Gensan and Takeshiki, which eventually was to be connected by cable with Matsushima. That very morning Admiral Uriu with the Naniwa and a torpedo-boat had started to escort to the spot a naval transport Seiryo Maru, which was proceeding from Fusan with the necessary staff and material. These vessels were obviously in a very dangerous position, and in view of the recent regrettable occurrences all Admiral Kamimura’s arrangements for getting contact with the enemy if he came south had to be subservient to their safety.

He was lying as before at Osaki with his four armoured cruisers, his despatch-vessel Chihaya being at Takeshiki. The rest of Admiral Uriu’s division had started to take up their day patrol positions, Niitaka for section C (20 miles north of Tsushima), the Tsushima at section A (20 miles about W.N.W. from Tsunoshima on the Japanese coast) and the Takachiho at section B between them. From these centres they worked 15 miles each way and thus covered the whole of the line Fusan—Tsunoshima. All the flotilla had come in from night guard, three divisions (11th, 17th, 18th) being ready for immediate service and two (15th and 19th) requiring to coal and water.

In these circumstances at 8.0 a.m. he ordered his own division to prepare to steam up the Western Channel. The Chihaya was called from Takeshiki and the Niitaka told by wireless to close on the Naniwa and inform her of the danger and that he himself was coming to a rendezvous 20 miles east of Unkofskago Bay (that is off Cape Clonard) before sunset.

The 15th and 19th torpedo divisions were to coal and meet him there, while the other three divisions were to take over the duty of patrol. On these orders the 17th and 18th divisions proceeded to stations 10 miles respectively west and east of Okinoshima, while the 11th division apparently took patrol section D in the Western Channel between Osaki and Sentinel Island off Cargodo.

At 8.35 the Admiral started with the armoured cruisers up the Western Channel, but in an hour’s time had seen cause to modify his arrangements. By 9.40 the Chihaya had joined, and she was sent ahead at full speed to try to overtake the Chukupen transport and send her back. This done, she was to rejoin off Cape Tikmenev, outside Ulsan. Half an hour later he received a message from the Staff at Tokyo, saying that they regarded the Naniwa and her consorts as being in danger. Whether or not as a consequence of this intimation, his next step was to call both the Takachiho and Tsushima to leave their guard stations and join him at the Cape Clonard rendezvous. The reason he took this step is nowhere explained.10

The next communication he had from the Staff was at 3.40, when he learnt that at 9.30 the enemy’s cruisers and flotilla had been seen going south-east past Kodrika Point, just south of Gensan. By that time he knew the Naniwa and Niitaka had met, but they had no news of the enemy or the transport. As he approached his rendezvous there was still no news, and at 5.30 he issued his orders for the night. The squadron would turn back south at 7.0 at ten knots for a rendezvous in patrol section B. (Position 285, 30 miles E.

![]() N. of Mitushima), reaching it at 4 A.M. At the same hour the Niitaka was to be 23 miles N. by W, of Minoshima (Position 498) and the Chihaya off Cape Tikmenev (26 miles E. by N.

N. of Mitushima), reaching it at 4 A.M. At the same hour the Niitaka was to be 23 miles N. by W, of Minoshima (Position 498) and the Chihaya off Cape Tikmenev (26 miles E. by N.

![]() N., Position 390), and they were to remain there guarding his right and left respectively till further orders. Most of the torpedo-boats missed him as the weather was growing thick. Two only joined, and as it was coming on to blow they were sent back with instructions to collect all boats they could at the O-Ura wireless station, and there await instructions. At 6.22 the Naniwa and Niitaka joined him, and half an hour later the Commander-in-Chief’s instructions about keeping fast hold of the Straits at last came to hand. Admiral Kamimura’s dispositions had already anticipated them, and at 7.0 he turned south.

N., Position 390), and they were to remain there guarding his right and left respectively till further orders. Most of the torpedo-boats missed him as the weather was growing thick. Two only joined, and as it was coming on to blow they were sent back with instructions to collect all boats they could at the O-Ura wireless station, and there await instructions. At 6.22 the Naniwa and Niitaka joined him, and half an hour later the Commander-in-Chief’s instructions about keeping fast hold of the Straits at last came to hand. Admiral Kamimura’s dispositions had already anticipated them, and at 7.0 he turned south.

Directly afterwards the Takachiho appeared and as there was still no news of the Chihaya and the transport, he presently dropped her to keep up communication. He also heard from the Tsushima that she had missed him but had picked up one torpedo-boat division and was following him. Carrying on past his rendezvous he was by 7.0 next morning (July 1) a little north of Okinoshima. The dawn had brought no sign of the enemy, and he turned 16 points back towards his rendezvous in section B (Pos. 385), a course which took him quickly to the Tsushima. She had only managed to keep two torpedo-boats with her, and they were at once sent in to combine with other divisions in patrolling the Western Channel.

By 11.0 he again reached his rendezvous in Section B., but the only news was from the Takachiho to say she had found the Chihaya, who reported the work at Chukupen done and the transport safe on her way back, and that she herself was coming on to rejoin. Of the enemy there was no trace. They seemed completely lost, and mindful presumably of what had occurred during the last raid, Admiral Kamimura, increasing to 11 knots, turned round again S. 38° W. for the fatal area where the Eastern Channel cut the transport route from Shimonoseki to Hakko.

All day he held this course, receiving no intelligence except a report from Gensan that the Russians had apparently gone northward the previous afternoon, and by 6.0 he had reached the southern limit of the strait. He had now with his Flag besides his four armoured cruisers, the Naniwa, Takachiho, and Tsushima, and was steaming in single line ahead. The Chihaya and Niitaka were the only two scouts remaining out, an arrangement for which there seems no justification. In default of an explanation we can only put it down to bad leading and cramped handling of his force. Even on elementary principles to keep three of his five light cruisers tied to the tail of his battle division, which was superior to the enemy he was seeding, was an inexplicable mistake and in this case it condemned him to failure. Had he made even the most ordinary attempt to feel round him, he could scarcely have failed to get contact with the Russians in such a way as to force them to an action. For at this time he must have been steaming approximately on the same course as the enemy without seeing them. About noon,11 that is two hours after he turned back for the strait, they were passing Okinoshima, which they could just see on the horizon. They must have been steaming very slow, for by 5.0 they were only just entering the strait. Admiral Kamimura, who had been doing 11 knots, would then have been somewhere on their starboard quarter, and, if his light cruisers had been spread, he must have got contact and been able to cut off their retreat. As it was, by keeping his cruisers in the line he blind-folded himself and ruined his chance.

The Russians, so far as can be gathered from their known positions, must have been hanging about on the scene of their last exploit, for it was not till after 6.30 p.m. that they were through the channel and turned west for Quelpart. By that time Admiral Kamimura, keeping his speed and still completely ignorant of their whereabouts, must have passed them; for the first intimation which he had of their presence was a wireless call at 6.14 from the Naniwa, who was in the rear of the line. But there was interference; the message could not be read, and the Admiral held on. Twenty minutes later distant smoke could be seen about east by north, and then, at 6.40, there came into view the three Vladivostok cruisers, “coming south,” about 15 miles away.12

It was far too late to hope for any good with his squadron, but he at once turned N. 60° E. “to press the enemy,” as he says, towards Okinoshima, where the 17th and 18th torpedo-boat divisions should be in position to cut off their retreat. He also kept making to Tsutsu the cypher warning, “Enemy sighted, send torpedo-boats,” and tried to enforce it by firing shotted rounds towards Takeshiki, which the Russians believed were fired at them.

The moment he had put his helm over the enemy had turned back in quarter-line prepared for a retiring action and were now running off as fast as they could gather speed. At first the courses, of the squadrons inclined to each other and as the Japanese began to work up their speed the range was found to be diminishing. The Rurik, moreover, could be seen to be lagging and there was some hope of bringing on an action. The Tsushima was now sent away at full speed to bring up the flotilla, and the other two cruisers of the light division were ordered to drop to 15 knots, while the armoured ships held on at 19. But soon the courses became parallel; the Rurik, after falling as low as 15 knots, began to recover her speed; and though the Japanese worked up to 20 knots they could gain no more on the chase. By 8.0, when the sun had set, the range was still from eight to ten miles, and the enemy could scarcely be seen. In a few minutes they were completely lost to sight, but there was still hope. Just before sunset distant forms had been made out which could only be the torpedo-boats of the Okinoshima patrol, and the enemy were heading straight for them. Sure enough at 8.17 the Russian cruisers suddenly began working their searchlights and firing; their position was again revealed, and Admiral Kamimura, taking care to train his own searchlights to starboard to prevent the enemy doubling back unseen, held on in chase.

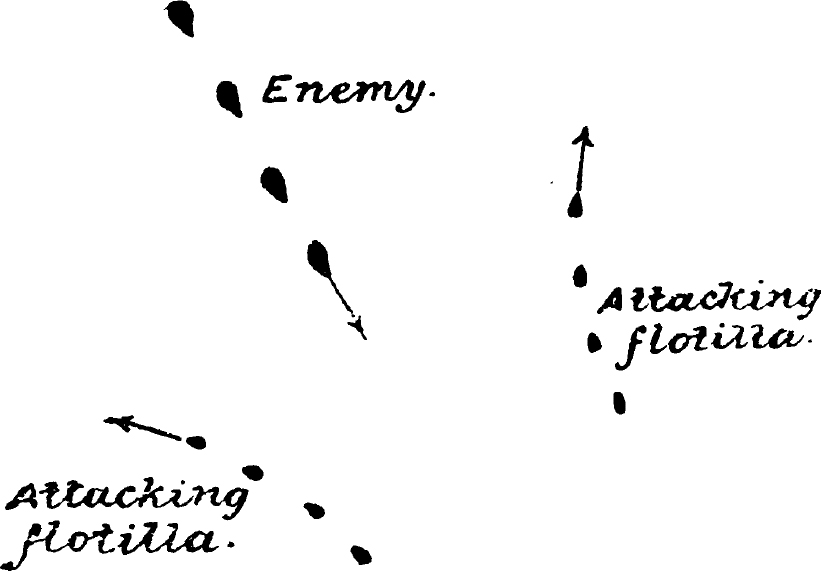

Both torpedo divisions were, in fact, attacking. Neither had seen anything of the enemy as they came south, but at 7.55 the 17th division, west of the island, had seen smoke to the southward as the Russians ran from the Japanese cruisers at full speed. Five minutes later the 18th division saw it. Both at once turned for it and ran up in excellent position for attack. But so clear was the evening that both were detected at a distance of 2,000 (2,200 yards) to 3,000 (3,300 yards) metres, and were received with so heavy a fire that they were forced to haul off and wait till it grew darker. After letting the enemy pass they turned again and chased. But this time the Russians had put out their searchlights and though the torpedo-boats chased till nearly midnight they never recovered touch. It had come on to blow with a rising sea, and they were only second-class boats of 80 tons. So in spite of their nominal 24 knots, the enemy ran clean away from them and there was nothing to do but resume their guard stations.

Admiral Kamimura could do no better. When the Russians extinguished their searchlights he, of course, lost them altogether. Still he held on hoping that another flotilla attack would force them to reveal their position, and for another hour the blind chase continued. At about 10.0 he took in the code signal, “Enemy sighted, west of Okinoshima.” What was he to do? It might well mean that the enemy, as he feared, had doubled back south. The moon was up, and the night very clear; yet no sign of the enemy was to be seen, and he had the strictest orders not to chase wide unless contact was certain. He decided, therefore, his duty was to return to the straits, and after a short cast to the north-east he held back S.W.

![]() S. still at high speed. At midnight he met a boat of the 18th division that had been disabled in a collision. She reported the enemy had disappeared to the northward, but the Admiral merely reduced speed and held on as he was.13

S. still at high speed. At midnight he met a boat of the 18th division that had been disabled in a collision. She reported the enemy had disappeared to the northward, but the Admiral merely reduced speed and held on as he was.13

All next day, the 2nd, he continued to cruise in the Shimonoseki area, still fearing lest the enemy had doubled back. While thus engaged he received an anxious query from Admiral Togo, “In what direction do you think the enemy have gone? Let me know, as it affects my guard arrangements.” All that night he tried to get an answer back through Tsutsu, but in vain, and early on the 3rd he sent a torpedo-boat in to telegraph from Iki. He could only say they had been last seen going off north-eastward, but that he could not tell whether they might not have taken some chance to steal by him. He was keeping the strictest watch he could on the straits, but owing to the high wind his flotilla was in difficulties. The anxiety was still great, and all through the 3rd in response to reiterated orders from Tokyo that until Port Arthur fell he was not to move far away, he continued to cruise in the straits.14 Nor was it till the morning of the 4th he thought it safe to return to Osaki, and resume the normal dispositions.

Thus it was the Russians were able to make away unhindered. A slight change of course after the torpedo attack had sufficed to throw their pursuers off the track. Next morning, as they ran northward, they fell in with the British steamer Cheltenham of 3,700 tons from Otaru, laden with sleepers for the Fusan-Seoul railway. She was captured, and on the 3rd they were safe in Vladivostok again with their prize.

Once more Admiral Kamimura had failed to deal effectively with the embarrassing squadron. To what is the failure to be attributed? In a measure to bad luck, to the incalculable chances of the sea, but mainly to his neglect to minimise those chances by a sound system of watching the Straits. His arrangements undoubtedly left much to be desired. All through we note a loose hold on fundamental principles—a failure to base his operations scientifically on a clear conception of his function, and of the organic constitution of his force. His function was to bar the Straits and defend the military line of communications against a force of three armoured cruisers, one protected cruiser, and a weak flotilla. For this he was given four armoured cruisers, four protected cruisers, and a numerous flotilla. In his armoured cruisers he had in effect a superior battle division, and on general principles (being on the defensive) he should have kept it in such a position that it could not fail to strike his enemy, if they came near to doing what it was his function to prevent. To this end it should have been rigidly confined, and all scouting that was needed to give it timely warning should have been performed entirely by his other cruisers and the flotilla. Yet we see a recurring tendency to confuse the functions of the two sections of his force, a restless anxiety “to seek out” the enemy’s fleet with his battle division, or with his massed force, on any alarm and on quite inadequate information. The result was that not only did he miss decisive contact, but that he permitted the enemy to penetrate the vital area from which it was his primary object to exclude them.

No doubt in this case his restlessness was mainly due to the fact that the Chukupen detachment was in jeopardy, but it is doubtful whether this can justify his abandonment of the position he was charged to defend. The risk of the Russians finding the exposed detachment was no greater than the risk of his failing to find them, and the possible consequences of his own failure were far the greater. A patient occupation of the vital area with his armoured division was the key of the problem he had to solve; but in extenuation of his error it must not be forgotten that for moral reasons such an attitude of apparent inaction is always difficult to maintain. It may well have been that to satisfy public opinion and for the sake of enheartening his crews he was over anxious to seize any plausible occasion for inspiriting movement. But theoretically his whole handling of the situation was faulty, and theory justified itself in his succession of practical failures.

For the Japanese the incident did much to emphasise the critical situation. True, Admiral Kamimura had maintained the strategical position entrusted to him, but it was clear that the Vladivostok detachment must continue to occupy nearly twice its own force until it could be brought to action. Nothing could be withdrawn to strengthen Admiral Togo’s hands; he had even to face new calls. For after receiving Admiral Kamimura’s unsatisfactory answer to his query he felt it necessary to detach the Yakumo and Chiyoda from his over-strained force to a position 40 miles north of Shantung Promontory, so as to give timely warning of the raiders’ approach.15 He was worried, too, by communications from the Staff about the intentions of the enemy. There was no doubt, he was told, the Port Arthur squadron meant to join hands with the Vladivostok cruisers and then to meet the Baltic Squadron so as to form an overwhelming Pacific Fleet, or perhaps they would run into neutral ports to preserve the ships. Such and similar information of course told the Admiral nothing. It can only be taken as evidence that at Tokyo there was a growing nervousness and irritation at the failure of the Navy to recover the grip of the situation, which it had seemed to have had since the delivery of the first blow. It would appear that the Imperial Staff had never clearly understood that the immunity of the Army communications had been due to the inaction of the Russians rather than to what their own fleet could do against a force of almost equal strength. But now that the Port Arthur Squadron was recovering its activity the real situation was declaring itself with disturbing effect.

This unhealthy atmosphere was further aggravated by the state of affairs in Kwangtung. In spile of his promising opening General Nogi had been unable to make further progress. So far from advancing, it was all he could do to hold his own. The Russians who had fallen back but slightly to the formidable “Position of the Passes” were making heroic efforts to recapture the high ground of Chien-shan. They failed, but on his extreme left General Nogi was forced back to withdraw from the position at Lao-tso-shan which he had originally taken to the next headland to the eastward.

Here there was crying need of assistance from the sea. Unable to give it, Admiral Togo handed over to the General the whole of the Naval Brigade to be at his sole disposal. But the Russian gunboats and destroyers continued to worry his left, and he asked for further help. As sweeping had progressed a little, Admiral Togo ordered in two gunboats, and then as the Russian efforts increased the Chinyen and Itsukushima followed. He also ordered Admiral Dewa, who had the day watch, to use his ships in supporting the Army; but so thick was the weather he could do nothing. The result of the effort was that the coast-defence ship Kaimon, which was covering the sweeping operations, fouled a mine, and was lost, with her commander and over a score of officers and men.

It seems clear that ashore the apparent impotence of the fleet was breeding some ill-feeling. It must always be so, when a military force is engaged in doing what seems to them the work of the Navy. Nothing is more difficult than for an Army to realise the limitations of the sister service, and such tension has been the commonest feature of these operations from Drake’s failure at Lisbon to that of Sampson at Santiago. The note of the strained relations has always been that in the eyes of the Army the sister service shows backwardness in incurring danger. Failing to realise the difference between land and sea warfare soldiers have seldom been able to make sufficient allowance for the fact that the danger which holds back the Navy is not danger to men but danger to irreplaceable ships.

The real cause of such friction as existed was certainly that the Japanese Imperial Staff had under-estimated the Russian power of resistance. Until further sweeping had been done the fleet could effect no more, nor could the Army till it was reinforced; and the passage of the reinforcements only increased the strain at sea. The whole of the IXth Army Division, a Reserve brigade, and large quantities of field and heavy artillery were on their way from Japan in the usual unescorted groups and their movement laid new cares upon both sections of the fleet. Till the greater part of them were safe at Dalny the deadlock must continue.

At sea the monotony was broken by occasional alarms that the Russians were coming out, which gained weight from the knowledge that the destroyer Lieutenant Burakov, which had succeeded once before in getting through to Newchwang, had performed the feat again and that Admiral Skruidlov had been there to meet her. It was even rumoured he had sailed in her to take command at Port Arthur. These and similar alarms from time to time forced Admiral Togo to take up his intercepting positions. Inshore, moreover, there were constant conflicts between the opposed flotillas and mining vessels and the cruisers supporting them. The general result was that the Japanese sweeping and mining operations gradually dominated those of the Russians, and did something to improve the prospects of naval co-operation with the Army when the time should come for a further advance.

It was now within measurable distance and the period of arrested offence ashore was drawing to a close. Since Rear-Admiral Togo’s recall the Navy had been able to do nothing to establish the advanced depôt for General Oku and the Army Staff had had to take over the work. By dint of great exertions they had succeeded in organising a sea supply service of their own, and while it was being set on foot General Oku had been slowly moving northward. The way they solved the difficulty was to collect a large number of junks and send them round to Kinchau Bay. There they were loaded with supplies brought across the Isthmus from Talien, in Hand Bay, which had been constituted the Second Army’s base, and so the danger of passing round Port Arthur without escort was avoided. From Kinchau Bay they could proceed with little fear of interference up the coast to the new supply base which the Navy had surveyed at Gobo. By July 10th, General Oku had reached Kaiping and the system was in working order. He had now only to wait till he had accumulated three weeks supplies and then the general advance could begin. On July 14th Marshal Oyama arrived to take up the supreme command of all the armies, and a few days later Admiral Togo was informed that the advance northward was to be accompanied by a great effort to settle the business of Port Arthur, and that on the 21st a general assault on the Position of the Passes would take place. He at once set about preparing to support it on both flanks. The completion of the sweeping operations in Talien-hwan had relieved the pressure on the inshore craft, and Admiral Hosoya was instructed to organise from his command at Dalny a detachment which would proceed to the other side of the Peninsula and worry the Russian left flank. It was to consist of the coast-defence vessel Saiyen, three regular16 and two auxiliary gunboats and two torpedo-boats.

Such a detachment meant a considerable increase of strain, for its operations would have to be covered by a cruiser force in the Pe-chi-li Strait and this would entail a modification in the blockade arrangements just when the crisis seemed at hand. For a desperate dash of the Port Arthur squadron was now confidently expected as a result of the coming military movements, and the day before they were to begin the expectation was reinforced by a most disturbing piece of news. Early on the 20th all stations were informed that at dawn that morning three of the Vladivostok cruisers had passed the Tsugaru Strait.

The immediate conclusion of the Staff at Tokyo was that an attempt to join hands with the Port Arthur squadron was on foot, and their first order to Admiral Kamimura was to hold himself in readiness to proceed off Shantung at the shortest notice. So far then the concentration on which Admiral Togo’s plans were based was not affected. There were, however, minor complications which were peculiarly inopportune. In the first place the British China Squadron had just left Wei-hai-wei and the Japanese saw in the place a harbour of refuge which the Russians would not scruple to use in order to save their fleet if it were hard pressed. The other difficulty was that the cable between the Elliot Islands and the Sir James Hall Islands had broken down, and the only way Admiral Togo had of keeping up communication with Tokyo and Admiral Kamimura was by the precarious means of detaching a cruiser to make wireless contact between Thornton Haven and the Station at Peng-yong-do in the Sir James Hall Islands.

On the 21st, the day the military movements were to begin, came news which further confirmed the Staff impressions. After passing the Tsugaru Straits the Russians had disappeared to the south-eastward as though to make a wide sweep round the Japanese Islands. For the moment, however, the pressure was relieved by the weather. A recurrence of the rains made all movement ashore impossible, and General Nogi’s advance had to be postponed till the 23rd. During these days it would seem that Admiral Togo was without news from Tokyo owing probably to the interruption of the cable.17 At all events on the 23rd he issued his operation orders to the fleet without any idea that his instructions for the Straits Squadron had been over-ridden by the Staff at Tokyo and that Admiral Kamimura was no longer at the strategical centre.

In the meantime he had obtained information of value from prisoners captured by the blockading destroyers. Amongst them were two officers who had been despatched from the Viceroy and were trying to get back to Newchwang. From these men he learnt for certain the truth about the accident which the Sevastopol had met with when re-entering the port on June 23rd and that her repairs would not be finished for ten days. They also told him that Admiral Skruidlov was at Liau-yang and that Admiral Vitgeft was still in command at Port Arthur. He had designed the sortie of June 23rd, they said, merely as a reconnaissance and his determination was to preserve the squadron intact and attempt no offensive measures till the Baltic Fleet arrived. Whether this news were true or not it was obvious that Admiral Vitgeft’s hand might be forced by the Japanese Army, and on this basis Admiral Togo drew up his orders.

After explaining the general idea of the Third Army’s attack he impressed the principle that though the primary work of the fleet was to be ready to meet a sortie, it would also assist the operations of the army. The attack would develop on the 26th. At dawn on that day the Saiyen detachment would appear on the Russian left flank, while the Fifth Division with a special sweeping party would operate from Cap Island to prevent annoyance of the Japanese left from the sea, retiring each night to Terminal Head. The Third Division would keep watch 14 miles south of Liau-ti-shan and cover the Saiyen detachment. For the Sixth Division the day position was at Encounter Rock, and at night it was to withdraw out to sea to position 910 (65 miles north of Shantung Promontory). The battle squadron would be at Round Island, retiring at night to Chang-zu-do in the Blonde Islands. The disposition, it will be seen, constituted a blockade of the closest kind practicable under modern conditions, and the base idea which it indicates is still to prevent an escape. The order further explained that if the enemy’s whole squadron came out and tried to get south, all the fleet would assemble at Encounter Rock and form the line of battle as previously laid down. If it anchored outside at night or in fog the flotilla was to seize every chance to attack.18

The same night a brilliant little affair gave happy promise of the spirit in which the flotilla would interpret its instructions. So far as concerned tactical co-operation on the Japanese left flank the key of the situation was Takhe Bay, an inlet on General Nogi’s left front. On the 22nd some Russian destroyers had occupied it, and three of them decided to lie in wait there all night with the idea of entrapping Japanese mining vessels on their way to the entrance of the harbour. Amongst them was the Lieutenant Burakov, their best destroyer, who had so distinguished herself in keeping up communication with Newchwang. The trap, however, was detected by the Japanese local torpedo-boat patrol, and its commander obtained leave to attack. His plan was to use two picket-boats furnished by the Mikasa and Fuji. In these he placed his junior officers, while with his torpedo-boats and two auxiliary gunboats he stood by to cover them and divert the enemy’s attention. The trick proved a brilliant success. Two of the Russian destroyers were torpedoed at close range. The Burakov was one of them. She was sunk on the spot, and the other completely disabled. Nothing so encouraging had been done for weeks and as the boats returned in triumph General Nogi began to move.

In the course of the day, however, came news of quite another colour. The cable had been repaired and the first intelligence it brought was, that since the previous day the Vladivostok cruisers had been off Tokyo playing havoc with the trade. Admiral Togo promptly came to one of those sagacious decisions which were so characteristic of his conduct all through. Whatever damage the adventurous cruisers might inflict he would do his best to see they never got back to tell the tale. Notwithstanding, therefore, the weakening it entailed at the strategical centre he sent an order to Admiral Kamimura to take the necessary steps. “You must leave at once,” he telegraphed, “with the Second Division (that is, the four armoured cruisers) the Chihaya (despatch-vessel) and two divisions of first-class torpedo-boats for the west side of Oshima (off the Tsugaru Strait) and Shirakami Zaki to bar the return of the Vladivostok Squadron which you will attack with your utmost strength. . . . You must guard the Tsushima Strait with the Fourth Division (Admiral Uriu’s cruisers) and the rest of your flotilla.” To provide against the possibility of the Russians being bent on carrying on to the Yellow Sea, east-about, he was further told to send the Chihaya to communicate with various signal stations on his way north,19 and if he found from them indications that the enemy was proceeding westward he was to return at once to Tsushima.

To the Commander-in-Chief’s unfailing eye the movement was obviously a diversionary raid and not an attempt to reach Port Arthur, though against that too his masterly plan provided. He calculated surely that the limit of the enemy’s radius of action must have been reached and that they would be already on their way back to Vladivostok. To all appearance he had them at his mercy. What then must have been his feelings when after many hours’ delay he received Admiral Kamimura’s reply? It was to the effect, that before Admiral Togo’s telegram reached him he had been ordered by the Chief of the Naval Staff at Tokyo to proceed not with his armoured cruisers only, but with both divisions and the best half of his flotilla to Toi Misaki, which is the first cape through the Van Diemen Strait at the extreme south of Japan. There he was to await further instructions. This order20 he informed his Commander-in-Chief he felt bound to obey and was already on his way to execute it.

At that very hour General Nogi was about to develop his attack on the Position of the Passes, and to the northward General Oku was forcing back the Russian relieving force from its position at Ta-shih-chiao. A sortie of the Port Arthur squadron was thereby rendered more and more imminent and Admiral Togo knew not only that the Vladivostok squadron must escape, but also that the corner stone of his combination had been torn from its place.

![]()

1 C.I.D., Vol. I., pages 231, 257.

2 The Russians in fact had laid no mines between Talien-hwan and a point 2

![]() miles west of Ping-tu-tau, except a few in Malanho Bay.

miles west of Ping-tu-tau, except a few in Malanho Bay.

3 Russian Military History, Vol. VIII, Part i., p. 363, Russian Edition.

4 The exact positions were:—

First Division.—40 miles E.S.E.

![]() E. of Round Island. Pos. 821.

E. of Round Island. Pos. 821.

Third Division.—58 miles S.E.

![]() E. of Encounter Rock. Pos. 910.

E. of Encounter Rock. Pos. 910.

Sixth Division.—45 miles S.

![]() E. of same. Pos. 1110.

E. of same. Pos. 1110.

5 Japanese Confidential History, Vol. VIII., Sec. i, pp. 416 et seq.

6 Flotilla Patrols. July i.

“In case of bad weather likely to cause the flotilla watch to be inefficient one cruiser of the duty sub-division to be left at Encounter Rock for the night.”

7 The Nisshin now bore Admiral Kataoka’s Flag, and though in battle order she and the Kasuga were attached to the First Division they still formed part of his own, the Fifth Division. The rest of that division was included in the “blockading” (or inshore) squadron,

8 Russian Military History, Volume VIII., Part ii., page 69. Admiral Vitgeft’s report of his failure was not sent off until June 27th, The Viceroy’s reply was despatched on July 1st,

9 Also written “Cheku Pien.”

10 The Japanese narrative is not quite clear here owing apparently to a misprint. The Naval Staff message is said to have been received at 10.9; the call to the two cruisers followed it, but is said to have been sent at 9.40. This time must be a misprint as 9.40 occurs again previous to the 10.9 entry.

11 According to the Rossiya, it was “about noon.” If the Russians were using Vladivostok time this would be 0.12 Japanese time; or 0.20, if they were using S.M.T.

12 The Rossiya gives “6.30” as the time the Japanese were seen. Admiral Kamimura says the Russians held on for some time after they were sighted as though they did not see his squadron as soon as he saw theirs. This is borne out by the times given, since the Russian 6.30 would mean Japanese 6.42 or 6.50.

13 According to the officer of the Rossiya, the Russians believed they were attacked by eleven boats, but there were in fact only eight. He also says that after the attack the Japanese fired on their own boats, but this the Japanese deny.

14 This message also expressed dissatisfaction with the bad working of his intelligence communications and suggested the possibility of using the old plan of “beacons on suitable peaks.”

15 In this he forestalled an idea of Admiral Alexeiev, who, on July 16th, told Admiral Vitgeft that at his next attempt the Vladivostok cruisers would try to meet him “even as far as Shantung.”

16 Heiyen, Chokai, Akagi.

17 The auxiliary cruiser Nippon Maru had been detailed to maintain wireless connection, but on the 20th the despatch-vessel Yaeyama was ordered to take her place.

18 For the text of the orders see Appendix J., p. 523.

19 The points at which the Chihaya was to call were Saigo in the Oki Islands, Hajiki Zaki in Sado Island and Henashi Zaki (50 miles south of the Tsugaru Straits).

20 The provenance of this order is not quite clear. The Japanese Confidential History, Ch.VIII., Sec. ii., says, “Admiral Ito, Chief of the Naval Staff, . . . thought it necessary to make the Second Squadron come at once from Takeshiki to Toi Misaki . . . At seven he sent to Admiral Kamimura the following telegraphic orders,” &c. But in Sec. iii. it says his orders came from the Imperial Staff, that he informed Admiral Togo that they came from the Imperial Staff and that he communicated directly with the Imperial Staff in reference to them. The explanation seems to be that Admiral Ito acted in two capacities. As Chief of the Naval Staff he only made suggestions to a Commander-in-Chief, but as Chief of the Naval Side of the Imperial Staff he conveyed the Emperor’s orders, and this is why Admiral Kamimura regarded the order as overriding that of his immediate chief.