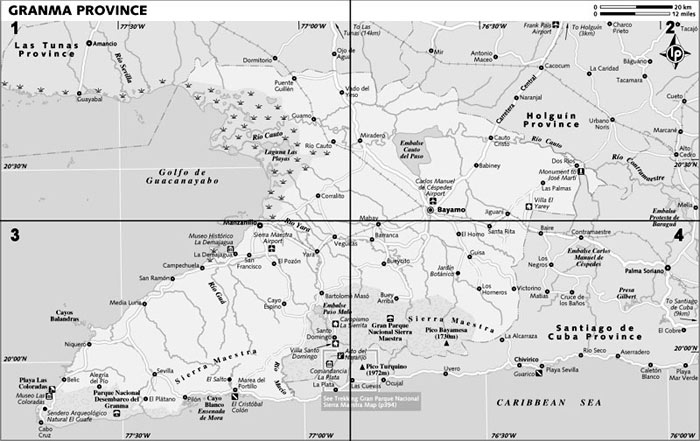

Granma Province |

|

BAYAMO

AROUND BAYAMO

DOS RÍOS & AROUND

YARA

GRAN PARQUE NACIONAL SIERRA MAESTRA

MANZANILLO

MEDIA LUNA

NIQUERO

PARQUE NACIONAL DESEMBARCO DEL GRANMA

PILÓN

MAREA DEL PORTILLO

Granma has ‘made in Cuba’ stamped all over it. This is the land where José Martí died, where Fidel Castro landed with his band of shipwrecked revolutionaries, and where Granma native Carlos Manuel de Céspedes freed his slaves and formally declared Cuban independence in 1868. And, if history doesn’t swing it, you can always ponder over the geographical significance of Cuba’s longest river (the Cauto), its most pristine coastal marine terraces (in Parque Nacional Desembarco del Granma) and its third-highest mountain (Pico Bayamesa; 1730m).

With much of its interior and southwestern coastal areas cut off from the main transport grid, one of Granma’s primary attractions is its isolation and the feisty individualism that goes with it. Street parties in towns such as Bayamo, Manzanillo and Pilón are a weekly occurrence here and are uniquely enlivened with homemade street snacks, hotly contested games of chess, and the kind of archaic street organs that were last seen in Europe when Cuba was still the property of Spain.

Juxtaposing pancake-flat rice fields with the soaring peaks of the Sierra Maestra, Granma is more rural than urban and even the two main cities of Bayamo and Manzanillo retain a faintly bucolic air.

But far from sucking on sugar stalks in the safety of their remote backcountry refuges, the resourceful locals are renowned for their creativity, particularly in the field of music. Two of the giants of Cuban nueva trova (philosophical folk guitar music) were born in Granma (Pablo Milanés in Bayamo and Carlos Puebla in Manzanillo), and in 1972 the province hosted a groundbreaking music festival that helped put this revolutionary new music style on Cuba’s – and Latin America’s – cultural map.

History

Stone petroglyphs and remnants of Taíno pottery unearthed in the Parque Nacional Desembarco del Granma suggest the existence of native cultures in the Granma region long before the arrival of the Spanish.

Columbus, during his second voyage, was the first European to explore the area, tracking past the Cabo Cruz Peninsula in 1494, before taking shelter from a storm in the Golfo de Guanacayabo. All other early development schemes came to nothing and by the 17th century Granma’s untamed and largely unsettled coast had become the preserve of pirates and corsairs.

Granma’s real nemesis didn’t come until October 10, 1868, when sugar-plantation owner Carlos Manuel de Céspedes called for the abolition of slavery from his Demajagua sugar mill near Manzanillo and freed his own slaves by example, thus inciting the First War of Independence.

Drama unfolded again in 1895 when the founder of the Cuban Revolutionary Party, José Martí, was killed in Dos Ríos just a month and a half after landing with Máximo Gómez off the coast of Guantánamo to ignite the Spanish-Cuban-American War.

Sixty-one years later, on December 2, 1956, Fidel Castro and 81 rebel soldiers disembarked from the yacht Granma off the coast of Granma province at Playa Las Coloradas. Routed by Batista’s troops while resting in a sugarcane field at Alegría del Pío, 12 or so survivors managed to escape into the Sierra Maestra, establishing headquarters at Comandancia La Plata. From there they fought and coordinated the armed struggle, broadcasting their progress from Radio Rebelde and consolidating their support among sympathizers nationwide. After two years of harsh conditions and unprecedented beard growth, the forces of the M-26-7 Movement triumphed in 1959.

Parks & Reserves

Granma has two expansive national parks: Gran Parque Nacional Sierra Maestra (sometimes called Parque Nacional Turquino) and Parque Nacional Desembarco del Granma. The latter is also a Unesco World Heritage Site.

Getting There & Around

You might have to resort to your first truck, guagua (local bus) or amarillo-inspired hitchhiking experience in Granma (see boxed text,). Bayamo is on the main Havana–Santiago Víazul bus and coche motor (cross-island) train routes, and a further train (but no Víazul bus) links Bayamo with Manzanillo. Outside this, you’re up against some of the poorest transport connections on the island, especially on the south coast. See individual towns for more details.

Return to beginning of chapter

BAYAMO

pop 143,844

Predating both Havana and Santiago, and cast for time immemorial as the city that kick-started Cuban independence, Bayamo has every right to feel self-important. Yet somehow it doesn’t. Instead, bucking standard categorization, Granma’s easygoing and understated provincial capital is one of the most peaceful and hassle-free places on the island.

That’s not to say that Bayameses aren’t aware of their history. Como España quemó a Sagunto, así Cuba quemó a Bayamo (meaning ‘as the Spanish burnt Sagunto, the Cubans burnt Bayamo’), wrote José Martí in the 1890s, highlighting the sacrificial role that Bayamo has played in Cuba’s convoluted historical development. But, while the self-inflicted 1869 fire might have destroyed most of the city’s classic colonial buildings (see below), it didn’t destroy its underlying spirit or its long-standing traditions.

Today, Bayamo is known for its cerebral chess players (Céspedes was the Kasparov of his day), tasty street snacks and quirky old-fashioned street organs (imported via Manzanillo). All three are on show at the weekly Fiesta de la Cubanía, one of the island’s most authentic street shows and Bayamés to the core.

History

Founded in November 1513 as the second of Diego Velázquez de Cuellar’s seven original villas (after Baracoa), Bayamo’s early history was marred by Indian uprisings and bristling native unrest. But with the indigenous Taínos decimated by deadly European diseases such as smallpox, the short-lived insurgency soon fizzled out. By the end of the 16th century, Bayamo had grown rich and was established as the region’s most important cattle-ranching and sugarcane-growing center. Frequented by pirates, the town filled its coffers further in the 17th and 18th centuries via a clandestine smuggling ring run out of the nearby port town of Manzanillo. Zealously counting up the profits, Bayamo’s new class of merchants and landowners lavishly invested their money in fine houses and an expensive overseas education for their offspring.

One such protégé was local lawyer-turned-revolutionary Carlos Manuel de Céspedes, who, defying the traditional colonial will, led an army against his hometown in 1868 in an attempt to wrest control from the conservative Spanish authorities. But the liberation proved to be short-lived. After the defeat of an ill-prepared rebel army by 3000 regular Spanish troops near the Río Cauto on January 12, 1869, the townspeople – sensing an imminent Spanish reoccupation – set their town on fire rather than see it fall into the hands of the enemy.

Bayamo was also the birthplace of Perucho Figueredo, composer of the Cuban national anthem, which begins, rather patriotically, with the words Al combate corred, Bayameses (Run to battle, people of Bayamo).

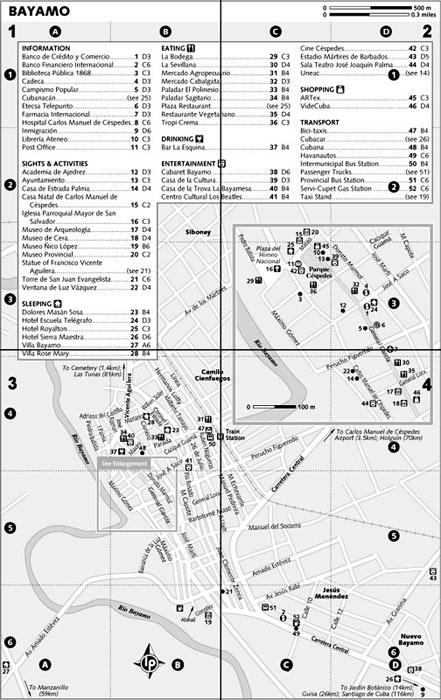

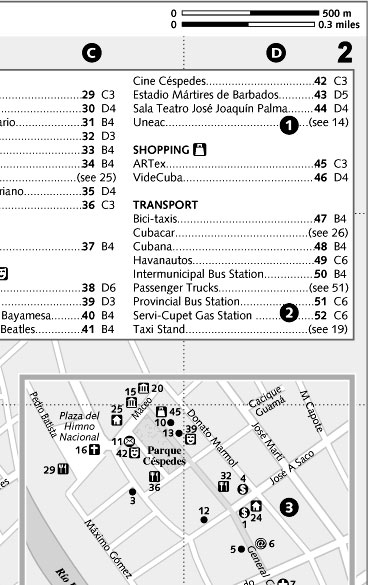

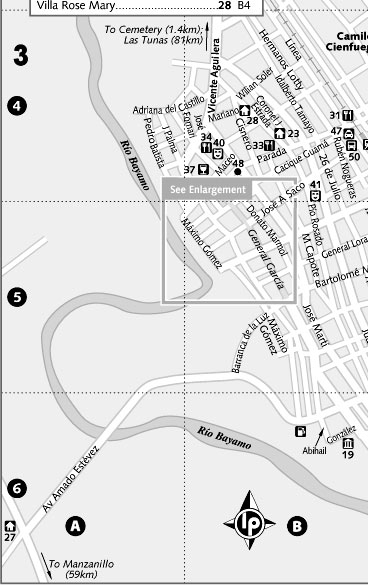

Orientation

Bayamo is centered on Parque Céspedes. The train station is located to the east of the park and the bus station to the southeast; they’re about 2km apart. General García (also known as El Bulevar), a bustling pedestrian shopping mall, leads from Parque Céspedes to Bartolomé Masó. Many of the facilities for tourists (including the bus station, Servi‑Cupet gas station and main hotel) are along the Carretera Central, southeast of town.

Information

BOOKSTORES

- Librería Ateneo (General García No 9) On the east side of Parque Céspedes.

INTERNET ACCESS & TELEPHONE

- Etecsa Telepunto (General García btwn Saco & Figueredo; per hr CUC$6;

8:30am-7:30pm) Quick, easy internet access.

8:30am-7:30pm) Quick, easy internet access.

LIBRARIES

- Biblioteca Pública 1868 (

42-64-87; Céspedes No 352;

42-64-87; Céspedes No 352;  9am-6pm Mon-Sat)

9am-6pm Mon-Sat)

MEDICAL SERVICES

- Farmacia Internacional (General García btwn Figueredo & Lora;

8am-noon & 1-5pm Mon-Fri, 8am-noon Sat & Sun)

8am-noon & 1-5pm Mon-Fri, 8am-noon Sat & Sun) - Hospital Carlos Manuel de Céspedes (

42-50-12; Carretera Central Km1)

42-50-12; Carretera Central Km1)

MONEY

- Banco de Crédito y Comercio (cnr General García & Saco;

8am-3pm Mon-Fri, 8-10am Sat)

8am-3pm Mon-Fri, 8-10am Sat) - Banco Financiero Internacional (

42-73-60; Carretera Central Km 1) In a big white building near the bus terminal.

42-73-60; Carretera Central Km 1) In a big white building near the bus terminal. - Cadeca (Saco No 101;

8:30am-noon & 12:30-5:30pm Mon-Sat, 8am-noon Sun)

8:30am-noon & 12:30-5:30pm Mon-Sat, 8am-noon Sun)

POST

- Post office (cnr Maceo & Parque Céspedes;

8am-8pm Mon-Sat)

8am-8pm Mon-Sat)

TRAVEL AGENCIES

- Campismo Popular (

42-42-00; General García No 112)

42-42-00; General García No 112) - Cubanacán (

42-22-90; Hotel Royalton, Maceo No 53) Arranges hikes to Pico Turquino (two/three/four days per person CUC$45/65/99), El Yarey (CUC$19) and Parque Nacional Desembarco del Granma (CUC$45), among other places.

42-22-90; Hotel Royalton, Maceo No 53) Arranges hikes to Pico Turquino (two/three/four days per person CUC$45/65/99), El Yarey (CUC$19) and Parque Nacional Desembarco del Granma (CUC$45), among other places.

Sights

One of Cuba’s leafiest and friendliest squares, Parque Céspedes is an attractive smorgasbord of grand monuments and big, shady trees. Facing each other in the center are a bronze statue of Carlos Manuel de Céspedes, hero of the First War of Independence, and a marble bust of Perucho Figueredo, with the words of the Cuban national anthem carved upon it. Marble benches and friendly Bayameses make this a nice place to linger. In 1868 Céspedes proclaimed Cuba’s independence in front of the Ayuntamiento (city hall) on the east side of the square.

The birthplace of the ‘father of the motherlands,’ Casa Natal de Carlos Manuel de Céspedes (Maceo No 57; admission CUC$1;  9am-5pm Tue-Fri, 9am-2pm & 8-10pm Sat, 10am-1pm Sun), is on the north side of the park. Born here on April 18, 1819, Céspedes spent the first 12 years of his life in this residence, and the Céspedes memorabilia inside is complemented by a collection of period furniture. It’s notable architecturally as the only two-story colonial house remaining in Bayamo and was one of the few buildings to survive the 1869 fire. Next door is the Museo Provincial (Maceo No 55; admission CUC$1) with a yellowing city document dating from 1567 and a rare photo of Bayamo immediately after the fire.

9am-5pm Tue-Fri, 9am-2pm & 8-10pm Sat, 10am-1pm Sun), is on the north side of the park. Born here on April 18, 1819, Céspedes spent the first 12 years of his life in this residence, and the Céspedes memorabilia inside is complemented by a collection of period furniture. It’s notable architecturally as the only two-story colonial house remaining in Bayamo and was one of the few buildings to survive the 1869 fire. Next door is the Museo Provincial (Maceo No 55; admission CUC$1) with a yellowing city document dating from 1567 and a rare photo of Bayamo immediately after the fire.

There’s been a church on the site of the Iglesia Parroquial Mayor de San Salvador since 1514. The current edifice dates from 1740 and the section known as the Capilla de la Dolorosa (donations accepted;  9am-noon & 3-5pm Mon-Fri, 9am-noon Sat) was another building to survive the 1869 fire. A highlight of the main church is the central arch, which exhibits a mural depicting the blessing of the Cuban flag in front of the revolutionary army on October 20, 1868. Outside, Plaza del Himno Nacional is where the Cuban national anthem, ‘La Bayamesa,’ was sung for the first time in 1868.

9am-noon & 3-5pm Mon-Fri, 9am-noon Sat) was another building to survive the 1869 fire. A highlight of the main church is the central arch, which exhibits a mural depicting the blessing of the Cuban flag in front of the revolutionary army on October 20, 1868. Outside, Plaza del Himno Nacional is where the Cuban national anthem, ‘La Bayamesa,’ was sung for the first time in 1868.

A forerunner of the national anthem, co-written by Céspedes (and also, confusingly, called ‘La Bayamesa’) was first sung from the Ventana de Luz Vázquez (Céspedes btwn Figueredo & Luz Vázquez) on March 27, 1851. A memorial plaque has been emblazoned onto the wall next to the wood-barred colonial window.

Next door is the Casa de Estrada Palma (Céspedes No 158), where Cuba’s first postindependence president, Tomás Estrada Palma, was born in 1835. A one-time friend of José Martí, Estrada Palma was disgraced after the Revolution for his perceived complicity with the US over the Platt Amendment. His birth house is now the seat of Uneac (Unión Nacional de Escritores y Artistas de Cuba; National Union of Cuban Writers and Artists), but you’ll find little about the famous former occupant inside.

The Torre de San Juan Evangelista (cnr José Martí & Amado Estévez) is to the southeast. A church dating from Bayamo’s earliest years stood at this busy intersection until it was destroyed in the great fire of 1869. Later, the church’s tower served as the entrance to the first cemetery in Cuba, which closed in 1919. The cemetery was demolished in 1940, but the tower survived. A monument to local poet José Joaquín Palma (1844–1911) stands in the park diagonally across the street from the tower, and beside the tower is a bronze statue of Francisco Vicente Aguilera (1821–77), who led the independence struggle in Bayamo.

Not far away, just off the main road, is the Museo Ñico López (Abihail González; admission CUC$1;  8am-noon & 2-5:30pm Tue-Sat, 9am-noon Sun) in the former officers’ club of the Carlos Manuel de Céspedes military barracks. On July 26, 1953, this garrison was attacked by 25 revolutionaries in tandem with the assault on Moncada Barracks in Santiago de Cuba in order to prevent reinforcements from being sent. Though a failure, Ñico López, who led the Bayamo attack, escaped to Guatemala, and he was the first Cuban to befriend Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara in 1954. López was killed shortly after the Granma landed in 1956.

8am-noon & 2-5:30pm Tue-Sat, 9am-noon Sun) in the former officers’ club of the Carlos Manuel de Céspedes military barracks. On July 26, 1953, this garrison was attacked by 25 revolutionaries in tandem with the assault on Moncada Barracks in Santiago de Cuba in order to prevent reinforcements from being sent. Though a failure, Ñico López, who led the Bayamo attack, escaped to Guatemala, and he was the first Cuban to befriend Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara in 1954. López was killed shortly after the Granma landed in 1956.

Bayamo’s main shopping street, Calle General García (also known as Paseo Bayamés) was pedestrianized and reconfigured with funky murals in the late 1990s. It’s a great place to catch the nuances of city life. Halfway along its course you’ll find the tiny Museo de Cera ( 42-65-25; General García No 261; admission CUC$1;

42-65-25; General García No 261; admission CUC$1;  9am-noon & 1-5pm Mon-Fri, 2-9pm Sat, 9am-noon Sun), Bayamo’s version of Madame Tussaud’s, with convincing waxworks of personalities such as Polo Montañez, Benny Moré and local hero Carlos Puebla. Next door is an equally tiny Museo de Arqueología (cnr General García & General Lora; admission CUC$1).

9am-noon & 1-5pm Mon-Fri, 2-9pm Sat, 9am-noon Sun), Bayamo’s version of Madame Tussaud’s, with convincing waxworks of personalities such as Polo Montañez, Benny Moré and local hero Carlos Puebla. Next door is an equally tiny Museo de Arqueología (cnr General García & General Lora; admission CUC$1).

Activities

The Cubans love chess, and nowhere more so than in Bayamo. Check out the streetside chess aficionados who set up on Saturday nights during the Fiesta de la Cubanía. The Academia de Ajedrez (José A Saco No 63 btwn General García & Céspedes) is the place to go to improve your pawn-king-four technique. Emblazoned on the wall of this cerebral institution, pictures of Che, Fidel and Carlos Manuel de Céspedes offer plenty of inspiration.

Forty-five-minute horse & cart tours can be arranged at the Cubanacán desk in the Hotel Royalton for CUC$4 per person.

Festivals & Events

Bayamo’s quintessential nighttime attraction is its weekly Fiesta de la Cubanía on Saturday at 8pm. This ebullient and long-standing street party is like nothing else in Cuba. Set up willy-nilly along Calle Saco, it includes the locally famous pipe organs, whole roast pig, a local oyster drink called ostiones and – incongruously in the middle of it all – rows of tables laid out diligently with chess sets. Dancing is, of course, de rigueur.

Sleeping

CASAS PARTICULARES

Rooms are spread around, but Calle Pío Rosada a good place to start looking.

Villa Rose Mary ( 42-39-84; reas61@gmail.com; Pío Rosado No 22 btwn Ramirez & Av Aguilera; r CUC$25;

42-39-84; reas61@gmail.com; Pío Rosado No 22 btwn Ramirez & Av Aguilera; r CUC$25;

) Don’t be fooled by the name, Ramón’s the man in charge here and his house is kitted out like a mini hotel with two bedrooms, big baths, safe security boxes, and a patio/roof terrace ripe for a spot of afternoon R and R. Get Ramón to brew you up a cafecito and quiz him on his excellent local knowledge.

) Don’t be fooled by the name, Ramón’s the man in charge here and his house is kitted out like a mini hotel with two bedrooms, big baths, safe security boxes, and a patio/roof terrace ripe for a spot of afternoon R and R. Get Ramón to brew you up a cafecito and quiz him on his excellent local knowledge.

Dolores Masán Sosa ( 42-29-74; Pío Rosado No 171 btwn Parada & William Soler; r CUC$25;

42-29-74; Pío Rosado No 171 btwn Parada & William Soler; r CUC$25;

) The freshly painted mint-green facade lures you toward Dolores Sosa’s house on Pío Rosado. Proceed up the outside staircase, past the well-polished relic of Detroit in the car port, to where two rooms with an independent entrance and an interconnecting door (if required) enjoy pride of place above the street action below. If it’s full, try Frank Licea Milan (

) The freshly painted mint-green facade lures you toward Dolores Sosa’s house on Pío Rosado. Proceed up the outside staircase, past the well-polished relic of Detroit in the car port, to where two rooms with an independent entrance and an interconnecting door (if required) enjoy pride of place above the street action below. If it’s full, try Frank Licea Milan ( 42-58-16) at No 73 or Juan Valdes (

42-58-16) at No 73 or Juan Valdes ( 42-33-24) at No 64.

42-33-24) at No 64.

HOTELS

Hotel Escuela Telégrafo (Formatur;  42-55-10; Saco No 108; s/d CUC$15/20;

42-55-10; Saco No 108; s/d CUC$15/20;  ) Always a good bet for budget travelers, the Telégrafo is one of Cuba’s best hotel escuelas (hotel schools) staffed by students learning the ropes in the tourist trade. This one is housed in a beautiful old colonial building on busy Calle Saco where big shuttered windows open out onto the street. Rooms are basic but clean, service is suitably perky, and there’s a decent restaurant adjacent to the bustling lobby downstairs. Ask here about the possibility of taking Spanish lessons.

) Always a good bet for budget travelers, the Telégrafo is one of Cuba’s best hotel escuelas (hotel schools) staffed by students learning the ropes in the tourist trade. This one is housed in a beautiful old colonial building on busy Calle Saco where big shuttered windows open out onto the street. Rooms are basic but clean, service is suitably perky, and there’s a decent restaurant adjacent to the bustling lobby downstairs. Ask here about the possibility of taking Spanish lessons.

Hotel Royalton (Islazul;

Hotel Royalton (Islazul;  42-22-90; Maceo No 53; s/d CUC$26/33;

42-22-90; Maceo No 53; s/d CUC$26/33;  ) Melting in with the colonial ambience of Parque Céspedes, the Royalton is Bayamo’s best hotel – and best bargain. The 33 rooms, though small, are cozy and well maintained with the four at the front opening out over the leafy central square. Downstairs there’s an attractive sidewalk terrace and the Plaza restaurant, and you can sunbathe in private on the roof. Handy water machines furnish the corridors.

) Melting in with the colonial ambience of Parque Céspedes, the Royalton is Bayamo’s best hotel – and best bargain. The 33 rooms, though small, are cozy and well maintained with the four at the front opening out over the leafy central square. Downstairs there’s an attractive sidewalk terrace and the Plaza restaurant, and you can sunbathe in private on the roof. Handy water machines furnish the corridors.

Villa Bayamo (Islazul;  42-31-02; s/d CUC$30/35;

42-31-02; s/d CUC$30/35;

) This out-of-town option (it’s 3km southwest of the center on the road to Manzanillo) has a definitive rural feel and a rather pleasant swimming pool overlooking fields at the back. Well-appointed rooms are in a larger main block or detached cabins off to the side. There’s a reasonable restaurant on-site.

) This out-of-town option (it’s 3km southwest of the center on the road to Manzanillo) has a definitive rural feel and a rather pleasant swimming pool overlooking fields at the back. Well-appointed rooms are in a larger main block or detached cabins off to the side. There’s a reasonable restaurant on-site.

Hotel Sierra Maestra (Islazul;  42-79-70; Carretera Central; s/d CUC$36/41;

42-79-70; Carretera Central; s/d CUC$36/41;

) Check before you jump in the pool here – there may be no water in it. With a ring of the Soviet ’70s about the place, the Sierra Maestra hardly merits the three stars it professes, although the rooms have had some much-needed attention in the last three years and the coffee and TV reception are better. Three kilometers from the town center, it’s OK for an overnighter.

) Check before you jump in the pool here – there may be no water in it. With a ring of the Soviet ’70s about the place, the Sierra Maestra hardly merits the three stars it professes, although the rooms have had some much-needed attention in the last three years and the coffee and TV reception are better. Three kilometers from the town center, it’s OK for an overnighter.

Eating

There’s some unique street food in Bayamo, sold from the stores along Calle Saco and in Plaza Céspedes. Aside from the places reviewed here, you’ll find decent comida criolla (Creole food) in the two city-center hotels, the Royalton (left) and the Telégrafo (left), both of which have atmospheric restaurants.

PALADARES

Paladar Sagitario (Donato Marmol No 107 btwn Maceo & Vicente Aguilera; meals CUC$7-9;  noon-midnight) The Sagitario’s been in the game for 13 years, knocking out such delicacies as chicken cordon bleu and pork chops topped with cheese on an attractive back patio with occasional musical accompaniment.

noon-midnight) The Sagitario’s been in the game for 13 years, knocking out such delicacies as chicken cordon bleu and pork chops topped with cheese on an attractive back patio with occasional musical accompaniment.

Paladar El Polinesio ( 42-24-49; Parada No 125 btwn Pío Rosado & Cisnero) The cheaper and cozier Polinesio has meals served upstairs in what used to be the family dining room.

42-24-49; Parada No 125 btwn Pío Rosado & Cisnero) The cheaper and cozier Polinesio has meals served upstairs in what used to be the family dining room.

RESTAURANTS

Tropi Crema ( 42-41-69;

42-41-69;  9am-9:45pm) In the absence of a Coppelia, the Tropi, on the southwest corner of Parque Céspedes, does its best – in pesos, of course.

9am-9:45pm) In the absence of a Coppelia, the Tropi, on the southwest corner of Parque Céspedes, does its best – in pesos, of course.

Restaurante Vegetariano (General García No 173;  7-9am, noon-2:30pm & 6-9pm;

7-9am, noon-2:30pm & 6-9pm;  ) Manage your expectations before you check out this peso place. This is Cuba where vegetarianismo is still in its infancy. Don’t expect nut roast, but you should be able to order something other than the ubiquitous omelette.

) Manage your expectations before you check out this peso place. This is Cuba where vegetarianismo is still in its infancy. Don’t expect nut roast, but you should be able to order something other than the ubiquitous omelette.

La Sevillana ( 42-14-95; General García btwn General Lora & Perucho Figueredo;

42-14-95; General García btwn General Lora & Perucho Figueredo;  noon-2pm & 6-10:30pm) Cuban chefs have a go at Spanish cuisine – paella and garbanzos (chickpeas). This is a new kind of peso restaurant, with a dress code (no shorts), a doorman in a suit, and a reservations policy. It’s OK, if you don’t mind the formalities.

noon-2pm & 6-10:30pm) Cuban chefs have a go at Spanish cuisine – paella and garbanzos (chickpeas). This is a new kind of peso restaurant, with a dress code (no shorts), a doorman in a suit, and a reservations policy. It’s OK, if you don’t mind the formalities.

La Bodega (

La Bodega ( 42-79-11; Plaza del Himno Nacional No 34; cover after 9pm CUC$3;

42-79-11; Plaza del Himno Nacional No 34; cover after 9pm CUC$3;  11am-1am) The best of both worlds. The front door opens out onto Bayamo’s main square; the rear terrace overlooks Río Bayamo and is fringed by a bucolic backdrop that will leave you wondering if you’ve been transported to an isolated country villa. La Bodega is Bayamo’s best restaurant and not only for its urban-rural juxtapositions. Try the beef and taste the coffee, or relax on the open terrace before the traveling troubadours arrive at 9pm.

11am-1am) The best of both worlds. The front door opens out onto Bayamo’s main square; the rear terrace overlooks Río Bayamo and is fringed by a bucolic backdrop that will leave you wondering if you’ve been transported to an isolated country villa. La Bodega is Bayamo’s best restaurant and not only for its urban-rural juxtapositions. Try the beef and taste the coffee, or relax on the open terrace before the traveling troubadours arrive at 9pm.

GROCERIES

Mercado agropecuario (Línea) The vegetable market is in front of the train station. There are many peso food stalls along here also.

Mercado Cabalgata (General García No 65;  9am-9pm Mon-Sat, 9am-noon Sun) This store on the main pedestrian street sells basic groceries.

9am-9pm Mon-Sat, 9am-noon Sun) This store on the main pedestrian street sells basic groceries.

Drinking

Bar La Esquina ( 42-17-31; cnr Donato Marmol & Maceo;

42-17-31; cnr Donato Marmol & Maceo;  11am-1am) International cocktails are served in this tiny corner bar replete with plenty of local atmosphere.

11am-1am) International cocktails are served in this tiny corner bar replete with plenty of local atmosphere.

Entertainment

Cine Céspedes ( 42-42-67; admission CUC$2) This cinema is on the western side of Parque Céspedes, next to the post office. It offers everything from Gutiérrez Alea to the latest Hollywood blockbuster.

42-42-67; admission CUC$2) This cinema is on the western side of Parque Céspedes, next to the post office. It offers everything from Gutiérrez Alea to the latest Hollywood blockbuster.

Centro Cultural Los Beatles (42-17-99; Zenea btwn Figueredo & Saco; admission 10 pesos;

Centro Cultural Los Beatles (42-17-99; Zenea btwn Figueredo & Saco; admission 10 pesos;  6am-midnight) Just as the West fell for the exoticism of the Buena Vista Social Club, the Cubans fell for the downright brilliance of the Fab Four. Guarded by life-size statues of John, Paul, George and Ringo, this quirky place hosts Beatles tribute bands (in Spanish) every weekend. Unmissable!

6am-midnight) Just as the West fell for the exoticism of the Buena Vista Social Club, the Cubans fell for the downright brilliance of the Fab Four. Guarded by life-size statues of John, Paul, George and Ringo, this quirky place hosts Beatles tribute bands (in Spanish) every weekend. Unmissable!

Uneac (Céspedes No 158; admission free;  4pm) You can catch heartfelt boleros on the flowery patio here in the former home of disgraced first president Tomás Estrada Palma, who is largely blamed for handing Guantánamo to the Yanquis.

4pm) You can catch heartfelt boleros on the flowery patio here in the former home of disgraced first president Tomás Estrada Palma, who is largely blamed for handing Guantánamo to the Yanquis.

Sala Teatro José Joaquín Palma ( 42-44-23; Céspedes No 164) In a stylish old church, this venue presents theater on Friday, Saturday and Sunday nights, while the Teatro Guiñol, also here, hosts children’s theater on Saturday and Sunday mornings.

42-44-23; Céspedes No 164) In a stylish old church, this venue presents theater on Friday, Saturday and Sunday nights, while the Teatro Guiñol, also here, hosts children’s theater on Saturday and Sunday mornings.

Cabaret Bayamo ( 42-51-11; Carretera Central Km 2;

42-51-11; Carretera Central Km 2;  9pm Fri-Sun) Bayamo’s glittery nightclub/cabaret opposite the Hotel Sierra Maestra draws out the locals on weekends in their equally glittery attire.

9pm Fri-Sun) Bayamo’s glittery nightclub/cabaret opposite the Hotel Sierra Maestra draws out the locals on weekends in their equally glittery attire.

Casa de la Trova La Bayamesa (cnr Maceo & Martí; admission CUC$1;  9pm) One of Cuba’s best in a lovely colonial building; closed Mondays.

9pm) One of Cuba’s best in a lovely colonial building; closed Mondays.

Casa de la Cultura ( 42-59-17; General García No 15) Wide-ranging cultural events, including art expos, on the east side of Parque Céspedes.

42-59-17; General García No 15) Wide-ranging cultural events, including art expos, on the east side of Parque Céspedes.

Estadio Mártires de Barbados (Av Granma) From October to April, there are baseball games at this stadium, approximately 1km northeast of the Hotel Sierra Maestra.

Shopping

ARTex (General García No 7) The usual mix of Che Guevara T-shirts and bogus Santería dolls on Parque Céspedes.

VideCuba (General García No 225;  8am-10pm) This outlet should meet your photographic requirements.

8am-10pm) This outlet should meet your photographic requirements.

Getting There & Away

AIR

Bayamo’s Carlos Manuel de Céspedes Airport (airport code BYM;  42-75-14) is about 4km northeast of town, on the road to Holguín. Cubana (

42-75-14) is about 4km northeast of town, on the road to Holguín. Cubana ( 42-75-07; Martí No 52) flies to Bayamo from Havana twice a week (CUC$103 one way, two hours). There are no international flights to or from Bayamo.

42-75-07; Martí No 52) flies to Bayamo from Havana twice a week (CUC$103 one way, two hours). There are no international flights to or from Bayamo.

BUS & TRUCK

The provincial bus station (cnr Carretera Central & Av Jesús Rabí) has Víazul (www.viazul.com) buses to several destinations.

The service to Havana also stops at Holguín (CUC$6, two hours 10 minutes), Las Tunas (CUC$6, 2½ hours), Camagüey (CUC$11, 5½ hours), Ciego de Ávila (CUC$17, seven hours 20 minutes), Sancti Spíritus (CUC$21, 9½ hours) and Santa Clara (CUC$26, 10¾ hours).

Passenger trucks leave from an adjacent terminal for Santiago de Cuba, Holguín, Manzanillo and Pilón. You can get a truck to Bartolomé Masó, as close as you can get on public transport to the Sierra Maestra trailhead. Ask which line is waiting for the truck you want, then join. The trucks leave when full and you pay as you board.

The intermunicipal bus station (cnr Saco & Línea), opposite the train station, receives mostly local buses of little use to travelers. However, trucks to Las Tunas and Guisa leave from here.

State taxis can be procured for hard-to-reach destinations such as Manzanillo (CUC$30), Pilón (CUC$70) and Niquero (CUC$65). Prices are estimates and will depend on the current price of gas. Nonetheless, at the time of writing it was cheaper to reach all these places by taxi than by hired car.

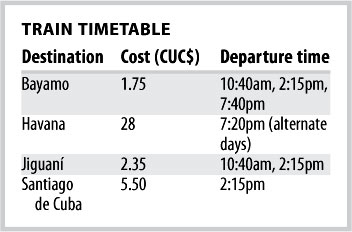

TRAIN

The train station ( 42-49-55; cnr Saco & Línea) is 1km east of the center. There are three local trains a day to Manzanillo (via Yara). Other daily trains serve Santiago and Camagüey. The long-distance Havana–Manzanillo train passes through Bayamo every other day (CUC$28).

42-49-55; cnr Saco & Línea) is 1km east of the center. There are three local trains a day to Manzanillo (via Yara). Other daily trains serve Santiago and Camagüey. The long-distance Havana–Manzanillo train passes through Bayamo every other day (CUC$28).

Getting Around

Cubataxi ( 42-43-13) can supply a taxi to Bayamo airport for CUC$3, or to Aeropuerto Frank País in Holguín for CUC$25. A taxi to Villa Santo Domingo (setting-off point for the Alto del Naranjo trailhead for Sierra Maestra hikes) or Comandancia La Plata will cost approximately CUC$35 one way. There’s a taxi stand in the south of town near Museo Ñico López.

42-43-13) can supply a taxi to Bayamo airport for CUC$3, or to Aeropuerto Frank País in Holguín for CUC$25. A taxi to Villa Santo Domingo (setting-off point for the Alto del Naranjo trailhead for Sierra Maestra hikes) or Comandancia La Plata will cost approximately CUC$35 one way. There’s a taxi stand in the south of town near Museo Ñico López.

Havanautos ( 42-73-75) is adjacent to the Servi-Cupet, while Cubacar (

42-73-75) is adjacent to the Servi-Cupet, while Cubacar ( 42-79-70; Carretera Central) is at the Hotel Sierra Maestra.

42-79-70; Carretera Central) is at the Hotel Sierra Maestra.

The Servi-Cupet gas station (Carretera Central) is between Hotel Sierra Maestra and the bus terminal as you arrive from Santiago de Cuba.

The main horse-cart route (one peso) runs between the train station and the hospital, via the bus station. Bici-taxis (a few pesos a ride) are also useful for getting around town. There’s a stand near the train station.

Return to beginning of chapter

AROUND BAYAMO

For a floral appreciation of Bayamo’s evergreen hinterland, head to the Jardín Botánico de Cupaynicu (Carretera de Guisa Km 10; admission with/without guide CUC$2/1), about 16km outside the city off the Guisa road. It’s on very few itineraries, so you can have the 104 hectares of the tranquil botanic gardens to yourself. There are 74 types of palms, scores of cacti, blooming orchids and sections for endangered and medicinal plants. The guided tour (Spanish only) gains you access to greenhouses, notable for the showy ornamentals.

To get here, take the road to Santiago de Cuba for 6km and turn left at the signposted junction for Guisa. After 10km you’ll see the botanic gardens sign on the right. Trucks in this direction leave from the intermunicipal bus station in front of the train station.

Return to beginning of chapter

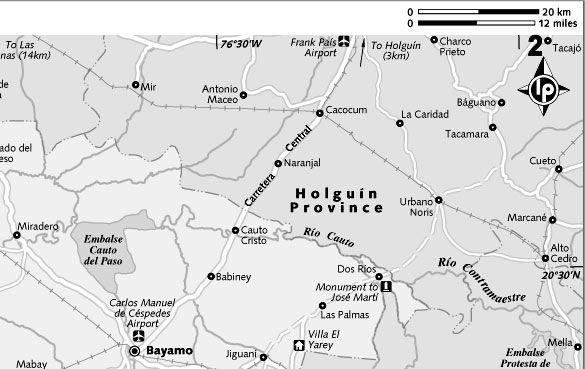

DOS RÍOS & AROUND

At Dos Ríos, 52km northeast of Bayamo, almost in Holguín, a white obelisk overlooking the Río Cauto marks the spot where José Martí was shot and killed on May 19, 1895. In contrast to other Martí memorials, it’s surprisingly simple and low-key. Go 22km northeast of Jiguaní on the road to San Germán and take the unmarked road to the right after crossing the Cauto.

Sleeping & Eating

Villa El Yarey (Cubanacán;  42-76-84; s/d CUC$31/46) Back toward Jiguaní, 23km southwest of Dos Ríos, is this relaxed, attractive hotel with 16 rooms on a ridge with an excellent view of the Sierra Maestra. This accommodation is perfect for those who want tranquility in verdant natural surroundings. Cubanacán organizes bird-watching trips here. Book through its office in Bayamo Click here.

42-76-84; s/d CUC$31/46) Back toward Jiguaní, 23km southwest of Dos Ríos, is this relaxed, attractive hotel with 16 rooms on a ridge with an excellent view of the Sierra Maestra. This accommodation is perfect for those who want tranquility in verdant natural surroundings. Cubanacán organizes bird-watching trips here. Book through its office in Bayamo Click here.

To get to Villa El Yarey from Jiguaní, go 4km east of town on the Carretera Central and then 6km north on a side road. From Dos Ríos proceed southwest on the road toward Jiguaní and turn left 2km the other side of Las Palmas. It makes an ideal stop for anyone caught between Bayamo and Santiago de Cuba, or for those taking the backdoor Bayamo–Holguín route. Note that public transport here is scant.

Return to beginning of chapter

YARA

pop 29,237

A small town with a big history, Yara – sandwiched halfway between Bayamo and Manzanillo amid vast fields of sugarcane –

is barely mentioned in most travel literature. While ostensibly agricultural, the town’s soul is defiantly Indian. The early Spanish colonizers earmarked it as one of their pueblos Indios (Indian towns) and a statue of rebel cacique (chief) Hatuey in the main square supports claims that the Spanish burned the dissenting Taíno chief here rather than in Baracoa. Chapter two of Yara’s history began on October 11, 1868, when it became the first town to be wrested from Spanish control by rebel forces led by Carlos Manuel de Céspedes. A second monument in the main square recalls this important event and the famous Grito de Yara (Yara Declaration) that followed, in which Céspedes proclaimed Cuba’s independence for the first time.

Just off the square, the Museo Municipal (Grito de Yara No 107; admission CUC$1;  8am-noon & 2-6pm Mon-Sat, 9am-noon Sun) chronicles Yara’s historical legacy along with the town’s role as a key supply center during the revolutionary war in the 1950s.

8am-noon & 2-6pm Mon-Sat, 9am-noon Sun) chronicles Yara’s historical legacy along with the town’s role as a key supply center during the revolutionary war in the 1950s.

There’s a Servi-Cupet here if you need a gas top-up. The Bayamo–Manzanillo train stops here three times a day.

Return to beginning of chapter

GRAN PARQUE NACIONAL SIERRA MAESTRA

Comprising a sublime mountainscape of broccoli-green peaks and humid cloud forest, and home to honest, hardworking campesinos (country folk), the Gran Parque Nacional Sierra Maestra is an alluring natural sanctuary that still echoes with the gunshots of Castro’s guerrilla campaign of the late 1950s. Situated 40km south of Yara, up a very steep 24km concrete road from Bartolomé Masó, this precipitous and untamed region contains the country’s highest peak, Pico Turquino (just over the border in Santiago de Cuba province), unlimited birdlife and flora, and the rebels’ one-time wartime headquarters, Comandancia La Plata.

History

History resonates throughout these mountains, the bulk of it linked indelibly to the guerrilla war that raged throughout this region between December 1956 and December 1958. For the first year of the conflict Fidel and his growing band of supporters remained on the move, never staying in one place for more than a few days. It was only in mid-1958 that the rebels established a permanent base on a ridge in the shadow of Pico Turquino. This headquarters became known as La Plata and it was from here that the combative Castro drafted many of the early revolutionary laws while he orchestrated the military strikes that finally brought about the ultimate demise of the Batista government.

Information

Aspiring visitors should check the current situation before arriving in the national park. Tropical storms and/or government bureaucracy have been known to put the place temporarily out of action. The best source of information is Cubamar ( 7-833-2523/4) in Havana, or you can go straight to the horse’s mouth by directly contacting Villa Santo Domingo (

7-833-2523/4) in Havana, or you can go straight to the horse’s mouth by directly contacting Villa Santo Domingo ( 56-53-02). These guys can put you in touch with the Centro de Información de Flora y Fauna next door (Click here). Additional information can be gleaned at the Cubanacán desk at the Hotel Royalton in Bayamo (Click here).

56-53-02). These guys can put you in touch with the Centro de Información de Flora y Fauna next door (Click here). Additional information can be gleaned at the Cubanacán desk at the Hotel Royalton in Bayamo (Click here).

Sights & Activities

Santo Domingo is a tiny village that nestles in a deep green valley beside the gushing Río Yara. Communally it provides a wonderful slice of peaceful Cuban campesino life that has carried on pretty much unchanged since Fidel and Che prowled these shadowy mountains in the late 1950s. If you decide to stick around, you can get a taste of rural socialism at the local school and medical clinic, or ask at Villa Santo Domingo about the tiny village museum. The locals have also been known to offer horseback riding, pedicure treatments, hikes to natural swimming pools and some classic old first-hand tales from the annals of revolutionary history.

The park closes at 4pm but rangers won’t let you pass after mid-morning, so set off early to maximize your visit.

All trips into the park begin at the end of the near-vertical, corrugated-concrete access road at Alto del Naranjo (after Villa Santo Domingo the road gains 750 vertical meters in 5km). To get there, it’s an arduous two-hour walk, or you can ask about passage in a bone-rattling Russian truck (formerly used by the military in Angola). There’s a good view of the plains of Granma from this 950m-high lookout, otherwise it’s just a launching pad for La Plata (3km) and Pico Turquino (13km).

Situated atop a crenellated mountain ridge amid thick cloud forest, Comandancia La Plata was first established by Fidel Castro in 1958 after a year on the run in the Sierra Maestra. Well camouflaged and remote, the rebel HQ was chosen for its inaccessibility and it served its purpose well – Batista’s soldiers never found it. Today it remains much as it was left in the ’50s, with 16 simple wooden buildings (including a small museum) providing an evocative reminder of one of the most successful guerrilla campaigns in history.

Comandancia La Plata is controlled by the Centro de Información de Flora y Fauna in the village of Santo Domingo. Aspiring guerrilla-watchers must first hire a guide at the park headquarters (CUC$11), get transport (or walk) 5km up to Alto del Naranjo, and then proceed on foot along a muddy track for the final 3km. For further information, contact Villa Santo Domingo or Cubanacán in Bayamo Click here.

Sleeping & Eating

There are three accommodation options for park-bound visitors.

Campismo La Sierrita (Cubamar;  59-33-26; s/d CUC$9/14) Situated 8km south of Bartolomé Masó you start to feel the slanting shadow of the mountains here. The campismo (camping installation) is 1km off the main highway on a very rough road and boasts 27 cabins with bunks, baths and electricity. There’s a restaurant, and a river for swimming. Ask at the desk about trips to the national park. To ensure it’s open and has space, reserve in advance with Cubamar (

59-33-26; s/d CUC$9/14) Situated 8km south of Bartolomé Masó you start to feel the slanting shadow of the mountains here. The campismo (camping installation) is 1km off the main highway on a very rough road and boasts 27 cabins with bunks, baths and electricity. There’s a restaurant, and a river for swimming. Ask at the desk about trips to the national park. To ensure it’s open and has space, reserve in advance with Cubamar ( 7-833-2523/4) in Havana or at the Campismo Popular (

7-833-2523/4) in Havana or at the Campismo Popular ( 42-42-00; General García No 112) office in Bayamo.

42-42-00; General García No 112) office in Bayamo.

Motel Balcón de la Sierra (Islazul;  59-51-80; s/d CUC$22/28;

59-51-80; s/d CUC$22/28;

) One kilometer south of Bartolomé Masó and 16km north of Santo Domingo, this attractively located place nestled in the mountain foothills is a little distant for easy access to the park. A swimming pool and restaurant lie perched on a small hill with killer mountain views, while 20 air-conditioned cabins are scattered below. A lovely natural ambience is juxtaposed with the usual basic but functional Islazul furnishings.

) One kilometer south of Bartolomé Masó and 16km north of Santo Domingo, this attractively located place nestled in the mountain foothills is a little distant for easy access to the park. A swimming pool and restaurant lie perched on a small hill with killer mountain views, while 20 air-conditioned cabins are scattered below. A lovely natural ambience is juxtaposed with the usual basic but functional Islazul furnishings.

Villa Santo Domingo (Islazul;

Villa Santo Domingo (Islazul;  56-53-68; s/d with breakfast CUC$32/37;

56-53-68; s/d with breakfast CUC$32/37;  ) This villa, 24km south of Bartolomé Masó, sits at the gateway to Gran Parque Nacional Sierra Maestra. There are 20 separate cabins next to the Río Yara and the setting, among cascading mountains and campesino huts, is idyllic. From a geographical aspect, this is the best jumping-off point for the La Plata and Turquino hikes. You can also test your lungs going for a challenging early morning hike up a painfully steep road to Alto del Naranjo (5km; 750m of ascent). Other attractions include horseback riding, river swimming and traditional music in the villa’s restaurant. If you’re lucky, you might even catch the wizened old Rebel Quintet, a group of musicians who serenaded the revolutionary army in the late 1950s. Fidel stayed here on various occasions (in hut 6) and Raúl Castro dropped by briefly in 2001 after scaling Pico Turquino at the ripe old age of 70.

) This villa, 24km south of Bartolomé Masó, sits at the gateway to Gran Parque Nacional Sierra Maestra. There are 20 separate cabins next to the Río Yara and the setting, among cascading mountains and campesino huts, is idyllic. From a geographical aspect, this is the best jumping-off point for the La Plata and Turquino hikes. You can also test your lungs going for a challenging early morning hike up a painfully steep road to Alto del Naranjo (5km; 750m of ascent). Other attractions include horseback riding, river swimming and traditional music in the villa’s restaurant. If you’re lucky, you might even catch the wizened old Rebel Quintet, a group of musicians who serenaded the revolutionary army in the late 1950s. Fidel stayed here on various occasions (in hut 6) and Raúl Castro dropped by briefly in 2001 after scaling Pico Turquino at the ripe old age of 70.

Getting There & Around

There’s no public transport from Bartolomé Masó to Alto del Naranjo. A taxi from Bayamo to Villa Santo Domingo should cost from CUC$30 to CUC$35 one-way. Ensure it can take you all the way; the last 7km before Villa Santo Domingo is extremely steep but passable in a normal car. Returning, the hotel should be able to arrange onward transport for you to Bartolomé Masó, Bayamo or Manzanillo.

A 4WD vehicle with good brakes is necessary to drive the last 5km from Santo Domingo to Alto del Naranjo; it’s the steepest road in Cuba with 45% gradients near the top. Russian trucks pass regularly, usually for adventurous tour groups, and you may be able to find a space on board for approximately CUC$7 (ask at Villa Santo Domingo). Alternatively, it’s a tough but rewarding 5km hike.

Return to beginning of chapter

MANZANILLO

pop 110,952

Bayside Manzanillo might not be pretty but – like most low-key Granma towns – it has an infectious vibe. Sit for 10 minutes in the dilapidated central park with its old-fashioned street organs and distinctive neo-Moorish architecture and you’ll quickly make a friend or three. With bare-bones transport links and only one grim state-run hotel, not many travelers make it out this far. As a result, Manzanillo is a good place to get off the standard guidebook trail and see how Cubans have learned to live with 50 years of rationing, austerity and school playground–style politics with their big neighbor in the north.

Founded in 1784 as a small fishing port, Manzanillo’s early history was dominated by smugglers and pirates trading in contraband goods. The subterfuge continued into the late 1950s, when the city’s proximity to the Sierra Maestra made it an important supply center for arms and men heading up to Castro’s revolutionaries in their secret mountaintop headquarters.

Manzanillo is famous for its hand-operated street organs, which were first imported into Cuba from France by the local Fornaris and Borbolla families in the early 20th century (and are still widely in use). The city’s musical legacy was solidified further in 1972 when it hosted a government-sponsored nueva trova festival that culminated in a solidarity march to Playa Las Coloradas (Click here).

Information

- Banco de Crédito y Comercio (cnr Merchán & Saco;

8:30am-3:30pm Mon-Fri, 8am-noon Sat)

8:30am-3:30pm Mon-Fri, 8am-noon Sat) - Cadeca (

57-71-25; Martí No 188;

57-71-25; Martí No 188;  8:30am-6pm Mon-Sat, 8am-1pm Sun) Two blocks from the main square. With few places accepting Convertibles here, you’ll need some Cuban pesos.

8:30am-6pm Mon-Sat, 8am-1pm Sun) Two blocks from the main square. With few places accepting Convertibles here, you’ll need some Cuban pesos. - Post office (cnr Martí & Codina) One block from Parque Céspedes.

Sights

IN TOWN

Although it may be a little dingy these days, Manzanillo is well known for its striking architecture, a psychedelic mélange of wooden beach shacks, Andalusian-style townhouses and intricate neo-Moorish facades. Check out the old City Bank of NY building (cnr Merchán & Doctor Codina), dating from 1913, or the ramshackle wooden abodes around Perucho Figueredo, between Merchán and JM Gómez.

Manzanillo’s central square, Parque Céspedes, is notable for its priceless glorieta (gazebo/bandstand), where Moorish mosaics, a scalloped cupola and arabesque columns set off a theme that’s replicated elsewhere. Completely restored a decade ago, the bandstand – an imitation of the Patio de los Leones in Spain’s Alhambra – shines brightly amid the urban decay. Nearby, a permanent statue of Carlos Puebla, Manzanillo’s famous homegrown troubadour, sits contemplatively on a bench admiring the surrounding cityscape.

On the eastern side of Parque Céspedes is the Museo Histórico Municipal (Martí No 226; admission free;  8am-noon & 2-6pm Tue-Fri, 8am-noon & 6-10pm Sat & Sun), giving the usual local history lesson with a revolutionary twist. There’s an art gallery next door. The city’s neoclassical Iglesia de la Purísima Concepción was initiated in 1805, but the twin bell towers were added in 1918. The church, named after Manzanillo’s patron saint, is notable for its impressive gilded altarpiece.

8am-noon & 2-6pm Tue-Fri, 8am-noon & 6-10pm Sat & Sun), giving the usual local history lesson with a revolutionary twist. There’s an art gallery next door. The city’s neoclassical Iglesia de la Purísima Concepción was initiated in 1805, but the twin bell towers were added in 1918. The church, named after Manzanillo’s patron saint, is notable for its impressive gilded altarpiece.

About eight blocks southwest of the park lies Manzanillo’s most evocative sight, the Celia Sánchez Monument. Built in 1990, this terra-cotta tiled staircase embellished with colorful ceramic murals runs up Calle Caridad between Martí and Luz Caballero. The birds and flowers on the reliefs represent Sánchez, lynchpin of the M-26-7 Movement and longtime aid to Castro, whose visage appears on the central mural near the top of the stairs. It’s a moving memorial with excellent views out over the city and bay.

OUTSIDE TOWN

The Museo Histórico La Demajagua (admission CUC$1;  8am-6pm Mon-Fri, 8am-noon Sun) started with a cry. Ten kilometers south of Manzanillo across the grassy expanses of western Granma lies La Demajagua, the site of the sugar estate of Carlos Manuel de Céspedes whose Grito de Yara and subsequent freeing of his slaves on October 10, 1868, marked the opening shot of Cuba’s independence wars. There’s a small museum here along with the remains of Céspedes’ ingenio (sugar mill), a poignant monument (with a quote from Castro) and the famous Demajagua bell that Céspedes tolled to announce Cuba’s (then unofficial) independence. In 1947, a then unknown Fidel Castro ‘kidnapped’ the bell and took it to Havana in a publicity stunt to protest against the corrupt Cuban government. To get to La Demajagua, travel south 10km from the Servi-Cupet gas station in Manzanillo, in the direction of Media Luna, and then another 2.5km off the main road, toward the sea.

8am-6pm Mon-Fri, 8am-noon Sun) started with a cry. Ten kilometers south of Manzanillo across the grassy expanses of western Granma lies La Demajagua, the site of the sugar estate of Carlos Manuel de Céspedes whose Grito de Yara and subsequent freeing of his slaves on October 10, 1868, marked the opening shot of Cuba’s independence wars. There’s a small museum here along with the remains of Céspedes’ ingenio (sugar mill), a poignant monument (with a quote from Castro) and the famous Demajagua bell that Céspedes tolled to announce Cuba’s (then unofficial) independence. In 1947, a then unknown Fidel Castro ‘kidnapped’ the bell and took it to Havana in a publicity stunt to protest against the corrupt Cuban government. To get to La Demajagua, travel south 10km from the Servi-Cupet gas station in Manzanillo, in the direction of Media Luna, and then another 2.5km off the main road, toward the sea.

Sleeping

Manzanillo – thank heavens – has a smattering of private rooms, as there’s not much happening on the hotel scene.

CASAS PARTICULARES

Adrián & Tonia (

Adrián & Tonia ( 57-30-28; Mártires de Vietnam No 49; r CUC$20-25;

57-30-28; Mártires de Vietnam No 49; r CUC$20-25;  ) This attractive casa, full of clever workmanship (double-glazed windows) and weeping plants, would stand out in any city, let alone Manzanillo. The position, on the terra-cotta staircase that leads to the Celia Sánchez monument, obviously helps. But youthful Adrián and Tonia have gone beyond the call of duty with a vista-laden terrace, Jacuzzi-sized cool-off pool and dinner provided in a paladar (privately owned restaurant) next door.

) This attractive casa, full of clever workmanship (double-glazed windows) and weeping plants, would stand out in any city, let alone Manzanillo. The position, on the terra-cotta staircase that leads to the Celia Sánchez monument, obviously helps. But youthful Adrián and Tonia have gone beyond the call of duty with a vista-laden terrace, Jacuzzi-sized cool-off pool and dinner provided in a paladar (privately owned restaurant) next door.

Villa Luisa ( 57-27-38; Rabena No 172 btwn Maceo & Masó; r CUC$20-25;

57-27-38; Rabena No 172 btwn Maceo & Masó; r CUC$20-25;

) Two newly renovated rooms in a clean, open house with coco palms and a small pool in the garden.

) Two newly renovated rooms in a clean, open house with coco palms and a small pool in the garden.

HOTELS

Hotel Guacanayabo (Islazul;  57-40-12; Circunvalación Camilo Cienfuegos; s/d low season CUC$17/22, high season CUC$18/24;

57-40-12; Circunvalación Camilo Cienfuegos; s/d low season CUC$17/22, high season CUC$18/24;

) The cheapest and most austere of Islazul’s Cuban hotels, the Guacanayabo looks like a tropical reincarnation of a Gulag camp. The fake flamingos in the lobby fail to lighten the mood, although the affable staff tries its best. Rooms are badly lit, if relatively clean, and the restaurant’s awaiting a visit from Gordon Ramsay’s Kitchen Nightmares.

) The cheapest and most austere of Islazul’s Cuban hotels, the Guacanayabo looks like a tropical reincarnation of a Gulag camp. The fake flamingos in the lobby fail to lighten the mood, although the affable staff tries its best. Rooms are badly lit, if relatively clean, and the restaurant’s awaiting a visit from Gordon Ramsay’s Kitchen Nightmares.

Eating & Drinking

Manzanillo is known for its fish, though strangely not a lot of the fresh seafood seems to find its way onto the plates in the restaurants. In common with many untouristed Cuban cities, the culinary scene here is grim. If in doubt, eat in your casa particular, or drop in on the weekend Sábado en la Calle (see below) where the locals cook up traditional whole roast pig.

Restaurante Licetera ( 57-52-42; Av Masó btwn Calles 9 & 10;

57-52-42; Av Masó btwn Calles 9 & 10;  noon-9:45pm) A decent indoor-outdoor place down near the seafront that specializes in local fish served with the head and bones on but still rather tasty. Prices are in moneda nacional (Cuban pesos).

noon-9:45pm) A decent indoor-outdoor place down near the seafront that specializes in local fish served with the head and bones on but still rather tasty. Prices are in moneda nacional (Cuban pesos).

Restaurante Yang Tsé ( 57-30-57; Merchán btwn Masó & Saco;

57-30-57; Merchán btwn Masó & Saco;  7am-10pm) Comida China is served for moneda nacional in this centrally located place with delusions of grandeur (there’s a dress code!). It overlooks Parque Céspedes and gets good reports from locals.

7am-10pm) Comida China is served for moneda nacional in this centrally located place with delusions of grandeur (there’s a dress code!). It overlooks Parque Céspedes and gets good reports from locals.

Cafetería La Fuente ( 57-82-54; cnr Avs Jesús Menéndez & Masó;

57-82-54; cnr Avs Jesús Menéndez & Masó;  8am-midnight) The Cubans are as stalwart about their ice cream as the British are about their cups of tea. Come what may, the scooper’s always in the tub. Join the line here to sweeten up your views of surrounding Parque Céspedes.

8am-midnight) The Cubans are as stalwart about their ice cream as the British are about their cups of tea. Come what may, the scooper’s always in the tub. Join the line here to sweeten up your views of surrounding Parque Céspedes.

Cafetería Piropo Kikiri ( 57-78-13; Martí btwn Maceo & Saco;

57-78-13; Martí btwn Maceo & Saco;  10am-10pm) This place has everything from ice-cream sandwiches to sundaes, available for Convertibles.

10am-10pm) This place has everything from ice-cream sandwiches to sundaes, available for Convertibles.

Dinos Pizza La Glorieta ( 57-34-57; Merchán No 221 btwn Maceo & Masó;

57-34-57; Merchán No 221 btwn Maceo & Masó;  8am-midnight) This small Cuba pizza chain could come in handy here. Perched on the main square, it’s run by the government restaurant group, Palmares, and accepts Convertibles.

8am-midnight) This small Cuba pizza chain could come in handy here. Perched on the main square, it’s run by the government restaurant group, Palmares, and accepts Convertibles.

Entertainment

As in most Cuban cities, Manzanillo’s best ‘gig’ takes place on Saturday evenings in the famed Sábado en la Calle, a riot of piping organs, roasted pigs, throat-burning rum and, of course, dancing locals. Don’t miss it!

Teatro Manzanillo (Villuendas btwn Maceo & Saco; admission 5 pesos;  shows 8pm Fri-Sun) Touring companies such as the Ballet de Camagüey and Danza Contemporánea de Cuba perform at this lovingly restored venue. Built in 1856 and restored in 1926 and again in 2002, this 430-seat beauty is packed with oil paintings, red flocking and original detail.

shows 8pm Fri-Sun) Touring companies such as the Ballet de Camagüey and Danza Contemporánea de Cuba perform at this lovingly restored venue. Built in 1856 and restored in 1926 and again in 2002, this 430-seat beauty is packed with oil paintings, red flocking and original detail.

Casa de la Trova ( 57-54-23; Merchán No 213; admission 1 peso) In the spiritual home of nueva trova, this is not the hallowed musical shrine it ought to be. In fact, it was being renovated at the time of writing.

57-54-23; Merchán No 213; admission 1 peso) In the spiritual home of nueva trova, this is not the hallowed musical shrine it ought to be. In fact, it was being renovated at the time of writing.

Uneac (cnr Merchán & Concession) For traditional music you’re better off heading for this more dependable option, which has Saturday and Sunday night peñas (musical performances) and painting expos.

Cabaret Salón Rojo ( 57-51-17;

57-51-17;  8pm-midnight Tue-Sat, 8pm-1am Sun) This place on the north side of Parque Céspedes has an upstairs terrace overlooking the square, for drinks (pay in pesos) and dancing.

8pm-midnight Tue-Sat, 8pm-1am Sun) This place on the north side of Parque Céspedes has an upstairs terrace overlooking the square, for drinks (pay in pesos) and dancing.

Cine Popular (Av 1 de Mayo;  Tue-Sun) This is the town’s top movie house.

Tue-Sun) This is the town’s top movie house.

Getting There & Away

AIR

Manzanillo’s Sierra Maestra Airport (airport code MZO;  57-75-20) is on the road to Cayo Espino, 8km south of the Servi-Cupet gas station in Manzanillo. Cubana (

57-75-20) is on the road to Cayo Espino, 8km south of the Servi-Cupet gas station in Manzanillo. Cubana ( 57-49-84) has a nonstop flight from Havana once a week on Saturday (CUC$103, two hours). Skyservice (www.skyserviceairlines.com) flies directly from Toronto in winter and transfers people directly to Marea del Portillo.

57-49-84) has a nonstop flight from Havana once a week on Saturday (CUC$103, two hours). Skyservice (www.skyserviceairlines.com) flies directly from Toronto in winter and transfers people directly to Marea del Portillo.

A taxi between the airport and the center of town should cost approximately CUC$6.

BUS & TRUCK

The bus station ( 57-34-04) is northeast of the city center. There are no Víazul services to or from Manzanillo. This narrows your options down to local Cuban guaguas or trucks (no reliable schedules and long queues). Services run several times a day to Yara and Bayamo in the east and Pilón and Niquero in the south. For the latter destinations you can also board at the crossroads near the Servi-Cupet gas station and the hospital (which is also where you’ll find the amarillos).

57-34-04) is northeast of the city center. There are no Víazul services to or from Manzanillo. This narrows your options down to local Cuban guaguas or trucks (no reliable schedules and long queues). Services run several times a day to Yara and Bayamo in the east and Pilón and Niquero in the south. For the latter destinations you can also board at the crossroads near the Servi-Cupet gas station and the hospital (which is also where you’ll find the amarillos).

TRAIN

All services from the train station on the north side of town are via Yara and Bayamo. Trains go to several destinations but they are painfully slow.

Getting Around

Cubacar ( 57-77-36) has an office at the Hotel Guacanayabo. There’s a sturdy road running through Corralito up into Holguín, making this the quickest exit from Manzanillo toward points north and east.

57-77-36) has an office at the Hotel Guacanayabo. There’s a sturdy road running through Corralito up into Holguín, making this the quickest exit from Manzanillo toward points north and east.

Horse carts (one peso) to the bus station leave from Doctor Codina between Plácido and Luz Caballero. Horse carts along the Malecón to the shipyard leave from the bottom of Saco.

Return to beginning of chapter

MEDIA LUNA

pop 15,493

One of a handful of small towns that punctuate the swaying sugar fields between Manzanillo and Cabo Cruz, Media Luna is worth a pit stop on the basis of its Celia Sánchez connections (see boxed text, opposite). The Revolution’s ‘first lady’ was born here in 1920 in a small clapboard house that is now the Celia Sánchez Museum (Paúl Podio No 111; admission CUC$1;  9am-noon & 2-5pm Tue-Sat, 9am-1pm Sun).

9am-noon & 2-5pm Tue-Sat, 9am-1pm Sun).

If you have time, take a stroll around this quintessential Cuban sugar town dominated by a tall soot-stained mill and characteristic clapboard houses decorated with gingerbread embellishments. Aside from the Sánchez museum, Media Luna showcases a lovely glorieta, almost as outlandish as the one in Manzanillo. The main park is the place to get a take on the local street theater while supping on peso fruit shakes and quick-melting ice cream.

Return to beginning of chapter

NIQUERO

pop 20,273

Niquero, a small fishing port and sugar town in the isolated southwest corner of Granma, is dominated by the local Roberto Ramírez Delgado sugar mill, built in 1905 and nationalized in 1960 (you’ll smell it before you see it). Like many Granma settlements, it is characterized by its distinctive clapboard houses and has a lively noche de Cubanilla, when the streets are closed off and dining is at sidewalk tables. Live bands replete with organ grinders entertain the locals.

Ostensibly, there isn’t much to do in Niquero, but you can explore the park, where there’s a cinema, and visit the town’s small museum. Look out for a monument commemorating the oft-forgotten victims of the Granma landing, who were hunted down and killed by Batista’s troops in December 1956.

Niquero makes a good base from which to visit the Parque Nacional Desembarco del Granma. There’s a Servi-Cupet gas station in the center of town and another on the outskirts toward Cabo Cruz.

Sleeping & Eating

Hotel Niquero (Islazul;  59-24-98; Esquina Martí; s/d CUC$22/29;

59-24-98; Esquina Martí; s/d CUC$22/29;

) Nestled in the middle of the small town, this low-key, out-on-a-limb hotel situated opposite the local sugar factory has dark, slightly tatty rooms with little balconies that overlook the street. The service here is variable, though the affordable on-site restaurant has been known to rustle up a reasonable beef steak with sauce. Better hunker down because it’s the only accommodation in town.

) Nestled in the middle of the small town, this low-key, out-on-a-limb hotel situated opposite the local sugar factory has dark, slightly tatty rooms with little balconies that overlook the street. The service here is variable, though the affordable on-site restaurant has been known to rustle up a reasonable beef steak with sauce. Better hunker down because it’s the only accommodation in town.

Return to beginning of chapter

PARQUE NACIONAL DESEMBARCO DEL GRANMA

Mixing unique environmental diversity with heavy historical significance, the Parque Nacional Desembarco del Granma (admission CUC$3) consists of 275 sq km of teeming forests, peculiar karst topography and uplifted marine terraces. It is also a spiritual shrine to the Cuban Revolution – the spot where Castro’s stricken leisure yacht Granma limped ashore in December 1956 to be met with a barrage of gunfire from Batista’s waiting army.

Named a Unesco World Heritage Site in 1999, the park protects some of the most pristine coastal cliffs in the Americas. Of the 512 plant species identified thus far, about 60% are endemic and a dozen of them are found only here. The fauna is equally rich, with 25 species of mollusk, seven species of amphibian, 44 types of reptile, 110 bird species and 13 types of mammal.

In El Guafe, archaeologists have uncovered the second-most important community of ancient agriculturists and ceramic-makers discovered in Cuba. Approximately 1000 years old, the artifacts discovered include altars, carved stones and earthen vessels along with six idols guarding a water goddess inside a ceremonial cave. As far as archaeologists are concerned, it’s probably just the tip of the iceberg.

Sights & Activities

The area is famous as the landing place of the yacht Granma, which brought Fidel and Revolution to Cuba in 1956 (see boxed text, opposite). A large monument and the Museo Las Coloradas (admission CUC$1;  8am-6pm Tue-Sat, 8am-noon Sun) just beyond the park gate marks the landing spot. The museum outlines the routes taken by Castro, Guevara and the others into the Sierra Maestra, and there’s a full-scale replica of the Granma.

8am-6pm Tue-Sat, 8am-noon Sun) just beyond the park gate marks the landing spot. The museum outlines the routes taken by Castro, Guevara and the others into the Sierra Maestra, and there’s a full-scale replica of the Granma.

About eight kilometers southwest of Las Coloradas is the easy 3km-long Sendero Arqueológico Natural El Guafe (admission CUC$3), the park’s only advertised nature/archaeological trail. An underground river here has created 20 large caverns, one of which contains the famous ĺdolo del Agua, carved from stalagmites by pre-Columbian Indians. You should allow two hours for the stroll in order to take in the butterflies, 170 different species of birds (including the tiny colibrí), and multiple orchids. There’s also a 500-year-old cactus. A park guard can guide you through the more interesting features for an extra CUC$2.

The park is flecked with other trails, but access to them is limited. Inquire about guided excursion with Cubamar in Havana. Cuban students have recounted fascinating expeditions retracing the footsteps of the Granma survivors from Alegrío del Pío into the Sierra Maestra.

Three kilometers beyond the El Guafe trailhead is Cabo Cruz, a classic fishing port with skiffs bobbing offshore and sinewy men gutting their catch on the golden beach. There’s not much to see here except the 33m-tall Vargas lighthouse, which was erected in 1871. An exhibition room labeled ‘Historia del Faro,’ inside the adjacent building, has lighthouse memorabilia and is open sporadically.

There’s good swimming and shore snorkeling east of the lighthouse; watch out for strong currents.

Sleeping & Eating

Campismo Las Coloradas (Cubamar; Carretera de Niquero Km 17; s/d CUC$8/12;  ) A Category 3 campismo with 28 duplex cabins standing on 500m of murky beach, 5km southwest of Belic, just outside the park. All cabins have air-con and baths and there’s a restaurant, a games hall and water-sport rental on-site. Las Coloradas underwent a lengthy reconstruction following damage inflicted by Hurricane Dennis in 2005. You can book through Cubamar in Havana.

) A Category 3 campismo with 28 duplex cabins standing on 500m of murky beach, 5km southwest of Belic, just outside the park. All cabins have air-con and baths and there’s a restaurant, a games hall and water-sport rental on-site. Las Coloradas underwent a lengthy reconstruction following damage inflicted by Hurricane Dennis in 2005. You can book through Cubamar in Havana.

Getting There & Away

Ten kilometers southwest of Media Luna the road divides, with Pilón 30km to the southeast and Niquero 10km to the southwest. Belic is 16km southwest of Niquero. It’s another 6km from Belic to the national park entry gate.

If you don’t have your own transport, getting here can be tough. Irregular buses go as far as the Campismo Las Coloradas daily and there are equally infrequent trucks from Belic. As a last resort, you can try the amarillos in Niquero. The closest gas stations are in Niquero.

Return to beginning of chapter

PILÓN

pop 11,904

Pilón is a small, isolated settlement wedged between the Marea del Portillo resorts and the Parque Nacional Desembarco del Granma. It is the last coastal town of any note before Chivirico over 150km to the east. Since its sugar mill shut down nearly a decade ago, Pilón has lost much of its raison d’être, though the people still eek out a living despite almost nonexistent transport links and a merciless bludgeoning from Hurricane Dennis in 2005.

Inspired by Fidel’s revolutionary call, the town’s inhabitants were quick to provide aid to the disparate rebel army after the Granma yacht landed nearby in 1956, and Castro muse Celia Sánchez briefly based herself here. The tiny Casa Museo Celia Sánchez Manduley (admission CUC$1;  9am-5pm Mon-Sat, 9am-1pm Sun) has been named in her honor – though it functions mainly as a local history museum.

9am-5pm Mon-Sat, 9am-1pm Sun) has been named in her honor – though it functions mainly as a local history museum.

There’s a popular dance in Cuba called the pilón (named after the town), which imitates the rhythms of pounding sugar. Your best chance of seeing it is to attend a festive Sábado de Rumba, Pilón’s weekly street party – similar to those in Manzanillo and Bayamo – with whole roast pig, shots of rum and plenty of live music. The hotels at Marea del Portillo run a weekly Saturday evening transfer bus to Pilón for CUC$5 return.

Sleeping & Eating

Villa Turística Punta Piedra (Cubanacán;  59-70-62; s/d CUC$26/45;

59-70-62; s/d CUC$26/45;

) On the main road 11km east of Pilón and 5km west of Marea del Portillo, this small low-key resort, comprising 13 rooms in two single-story blocks, makes an interesting alternative to the larger hotel complexes to the east. There’s a restaurant here and an intermittent disco located on a secluded saber of sandy beach. The staff, once they’ve recovered from the surprise of seeing you, will be mighty pleased with your custom.

) On the main road 11km east of Pilón and 5km west of Marea del Portillo, this small low-key resort, comprising 13 rooms in two single-story blocks, makes an interesting alternative to the larger hotel complexes to the east. There’s a restaurant here and an intermittent disco located on a secluded saber of sandy beach. The staff, once they’ve recovered from the surprise of seeing you, will be mighty pleased with your custom.

Getting There & Around

Public transport in and out of Pilón is dire in both directions. The only regular bus is the Astro to Santiago de Cuba via Bayamo on alternate days – but this is no longer available to non-Cubans. Otherwise it’s car, long-distance bike, or winging it with the amarillos (for tips, see boxed text,).

The Servi-Cupet gas station is by the highway at the entrance to Pilón and sells snacks and drinks. Drivers should be sure to fill up here; the next gas station is in Santiago de Cuba nearly 200km away.

Return to beginning of chapter

MAREA DEL PORTILLO

There’s something infectious about Marea del Portillo, a tiny south-coast village bordered by two low-key all-inclusive resorts. Wedged into a narrow strip of dry land between the glistening Caribbean and the cascading Sierra Maestra, it occupies a spot of great natural beauty – and great history.

The problem for independent travelers is getting here. There is no regular public transport, which means that you may, for the first time, have to go local and travel with the amarillos. Another issue for beach lovers is the sand, which is of a light gray color and may disappoint those more attuned to the brilliant whites of Cayo Coco.

The resorts themselves are affordable and well maintained places but they are isolated; the nearest town of any size is lackluster Manzanillo 100km to the north. Real rustic Cuba, however, is a hop, skip and a jump outside the hotel gates.

Activities

There’s plenty to do here, despite the area’s apparent isolation. Both hotels operate horseback riding for CUC$5 per hour (usually to El Salto; see boxed text, below) or a horse-and-carriage sojourn along the deserted coast road for CUC$4. A jeep tour to Las Jaguas waterfall is CUC$49 and trips to Parque Nacional Desembarco del Granma start at about the same price. Trips can be booked at Cubanacán desks in either hotel.

The Marlin Dive Center ( 59-70-34), adjacent to Hotel Marea del Portillo, offers scuba diving for a giveaway CUC$25/49 per one/two immersions. A more exciting dive to the Cristóbal Colón wreck (sunk in the 1898 Spanish-Cuban-American War) costs CUC$70 for two immersions. Deep-sea fishing starts at CUC$200 for a boat (four anglers) plus crew and gear.

59-70-34), adjacent to Hotel Marea del Portillo, offers scuba diving for a giveaway CUC$25/49 per one/two immersions. A more exciting dive to the Cristóbal Colón wreck (sunk in the 1898 Spanish-Cuban-American War) costs CUC$70 for two immersions. Deep-sea fishing starts at CUC$200 for a boat (four anglers) plus crew and gear.

Other water excursions include a seafari (with snorkeling) for CUC$35, a sunset cruise for CUC$15 and a trip to uninhabited Cayo Blanco for CUC$25.

Sleeping & Eating

Hotel Marea del Portillo (Cubanacán;

Hotel Marea del Portillo (Cubanacán;  59-70-08; s/d all-inclusive CUC$70/100;

59-70-08; s/d all-inclusive CUC$70/100;

) It’s not Cayo Coco, but it barely seems to matter here. In fact, Marea’s all-round functionalism and lack of big-resort pretension seem to work well in this traditional corner of Cuba. The 74 rooms are perfectly adequate, the food buffet does a good job, and the dark sandy arc of beach set in the warm rain shadow of the Sierra Maestra is within baseball-pitching of your balcony/patio. Servicing older Canadians and some Cuban families means there is a mix of people here; plus plenty of interesting excursions to some of the island’s lesser heralded sights.

) It’s not Cayo Coco, but it barely seems to matter here. In fact, Marea’s all-round functionalism and lack of big-resort pretension seem to work well in this traditional corner of Cuba. The 74 rooms are perfectly adequate, the food buffet does a good job, and the dark sandy arc of beach set in the warm rain shadow of the Sierra Maestra is within baseball-pitching of your balcony/patio. Servicing older Canadians and some Cuban families means there is a mix of people here; plus plenty of interesting excursions to some of the island’s lesser heralded sights.

Hotel Farallón del Caribe (Cubanacán;  59-70-09; s/d all-inclusive CUC$95/120;

59-70-09; s/d all-inclusive CUC$95/120;

) Perched on a low hill with the Caribbean on one side and the Sierra Maestra on the other, the Farallón is Marea’s bigger and richer sibling. Cozy and comfortable all-inclusive facilities are complemented by five-star surroundings and truly magical views across Granma’s hilly hinterland. Exciting excursions can be organized at the Cubanacán desk here into the Parque Nacional Desembarco del Granma, or you can simply sit by the pool/beach and do absolutely nothing. The resort is popular with package-tour Canadians and is only open April through October.