6

THE INHERITED TRADITION

When Hagiwara Jūzō founded the school under the guidance and instruction of Niki Shinjūrō, the school would have been considered a comprehensive combat school, including but not confined to:

• sword quick draw

• hand-to-hand fighting

• projectile weapons

• rope skills

• chain and sickle

• quarterstaff

• the arts of the shinobi

• defensive magic

• mounted warfare

• martial philosophy

• secret traditions

When the school became an official school taught at the Keibukan dōjō, it is listed as a jūjutsu, kumiuchi, and taijutsu school, all of which are unarmed combat skills. This raises the question, how many of the traditions of Mubyōshi Ryū were passed on? If the school was registered as only teaching hand-to-hand combat, where did the other skills go, and for how long were the traditions passed on? The current grandmaster, Uematsu Sensei, is the inheritor of the unarmed combat tradition. The skills of the kusarigama (sickle and chain) are the result of his research, and the Mubyōshi Ryū Shinobi Arts and other scrolls were collected and presented by me, Mieko Koizumi, and Yoshie Minami. Through the multiple transcriptions and scrolls, we know that many of the skills continued to be passed on even into the nineteenth century, but the fact that a selection of them is no longer passed on shows that a concentration on unarmed fighting skills has led to a loss of sections of the school.

ADAPTING JŪJUTSU TO THE MODERN DAY

For an aficionado of jūjutsu, the images in this book may contain stances that appear peculiar and that resemble more of a karate attitude. For those who are not familiar, traditional jūjutsu often begins with a raised hand and, for want of a better word, a chopping motion, giving the iconic and wrongly titled “judo chop” its fame. Japanese martial arts start with this rigid chopping action, and kata (forms) are used to defend against them.

Karate, on the other hand, is not Japanese and was introduced from the Okinawan islands in the early twentieth century. The current grandmaster of Mubyōshi Ryū is also a teacher of traditional karate and decided that he would adopt a more karate-like attitude to the traditional jūjutsu. This may be horrific for some traditionalists, who may disagree with his intention (me included). However, know that the stances in this book are based on a karate attack and a jūjutsu response. Those who wish to return the skills to a more traditional slant may adopt the classic jūjutsu-style attack, a transition that will offer little difficulty.

That being said, lurking like a dragon at the rear of a cold cave is an argument that is at the forefront of my mind. It has to be understood that over the hundreds of years that traditional schools have existed, stagnation, dogma, and simplification have crept into their techniques, and what may once have been a very dynamic, versatile, and effective skill may in some schools have become a theater show of its original form. Kata may have lost the “middle elements,” the connecting flow between each position where body manipulation would have originally been found. It is my opinion that the world of Japanese martial arts needs a complete overhaul, and the skills need to be stripped back to their original incarnation. Keep this in mind as you study old schools.

Figure 6.1. Karate and jūjutsu opening stances. There are multiple versions of both karate and jūjutsu stances, and this image represents the basic differences. Each traditional school has its own version.

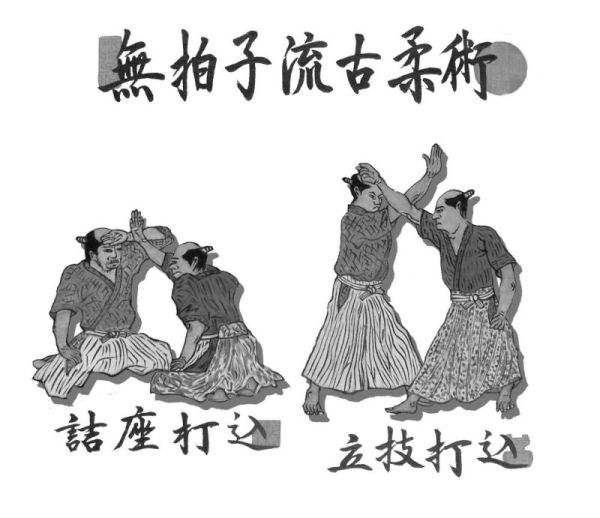

TO SIT OR NOT TO SIT, THAT IS THE QUESTION

The question of sitting or standing to execute a martial technique has long been a factor that never “sits” well with me. In both swordsmanship and grappling, adopting a seated position is sometimes used. Most people jump to the conclusion that such skills were performed when samurai sat together, but this is not as straightforward as it appears. There are often hierarchical seating positions to consider, the tradition of taking the longsword off the waist, the retaining of the shortsword in the sash, and the distance between the seated people—which could be some distance away. In addition, it appears that in some schools, skills that were once displayed and practiced from a standing position moved to be practiced while seated. This has led to schools of many arts using skills only when seated but which may have been established as standing combat.

I would like to suggest that the reader and any neophyte of the skills in this book keep in mind that most of these skills should be studied from a standing position, but that they can also be attempted while sitting. Retain this mind while remembering that it is the principle of the application that should be studied, not the detail. Some of the skills in the book change between both, but always remember that most skills would have started from a standing position. The argument behind this and its answer have yet to be satisfied, and a journey into discovering the truth behind “to sit or not to sit” is well outside of the scope of this work. Even though the argument cannot be settled, it is best to understand and consider these factors:

• All skills were originally developed to tackle unexpected situations, fast and unplanned.

• Most likely, the predominant number of skills were performed standing.

• Some skills were developed and originally used from a seated position.

• A samurai would not sit down with his katana in his belt, except in some cases. He may retain it at the waist while being present in ritual suicide or when arresting others, thus some skills may have been developed for those situations.

• At some point in the Edo Period—the period of peace and the last era of the samurai—traditional standing drills moved from being performed upright to being done from the floor in a seated position.

• It is important to note that this move from standing to seated has caused an immense complication in understanding what was originally intended as a sitting skill or a standing one.

• While Edo Period manuals—such as those found in Mubyōshi Ryū—state that a skill is done from a seated position, this may be a reflection of the trend to move to a seated position and may not have been the original way it was practiced, even though the schools’ scrolls themselves say so.

• This issue causes problems with the names of some scrolls, as some are considered to mean standing skills and some mean sitting skills. See the scroll list in appendix D.

In conclusion, understand that at present there is no definite way to establish those skills that should be performed seated and those that should be performed standing. Instead, apply yourself to understanding the concept of each skill from both positions.

Figure 6.2.

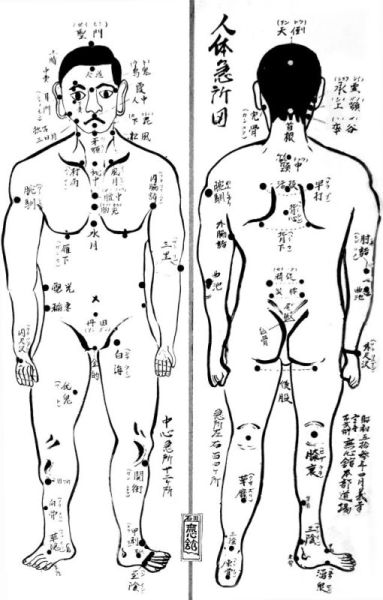

PRESSURE POINTS AND VITAL STRIKING AREAS

Striking vital points is a cornerstone of Japanese martial arts. Figure 6.3 shows the vital striking points on the human body and is studied in the main dōjō itself. These can be found in many arts.

Figure 6.3.