1 IDEALS AND MISSION

Art museums, like most institutions, are guided by ideals laid out in a statement of mission. Institutional goals vary in detail from one museum to the next, but generally art museums share a commitment to preserving the objects in their care for posterity and to making those objects available to the public. The British Museum “exists to illuminate the histories of cultures, for the benefit of present and future generations,” according to its Web site.1 Similarly, the mission of Washington's National Gallery of Art “is to serve the United States of America…by preserving, collecting, exhibiting, and fostering the understanding of works of art.”2 Halfway around the world, the National Palace Museum in Taiwan is dedicated to “protecting and preserving the 7000-year cultural legacy of China” and “bringing the Museum's collection to the global community.”3 Because of their role in protecting cultural memory and spreading public enlightenment, museums are viewed as important and socially benevolent institutions, worthy of community support and a charitable (tax-exempt) status.

What mission statements rarely articulate, however, is what is meant by benefit and whose artistic heritage is, or is not, collected and displayed. Who decides, and on what grounds, what qualifies as “art”? Social benefit is customarily defined in terms of education, but what constitutes the educational value of art? What do visitors learn on an outing to the local museum? For what purpose do art museums preserve and educate? In a recent interview, the director of the British Museum, Neil MacGregor, stated that museums today should embrace a vision of civic humanism in which the knowledge they generate “is to have a civic outcome.” What might that “civic outcome” look like?

As forward-looking institutions, museums have always been dedicated to building a better society, but visions of what constitutes it are always shifting. Consequently, museum priorities are not fixed in stone like their monolithic facades but subject to debate and modification as social needs change. Vaguely worded mission statements allow for change with no diminution of purpose. Change may appear subtle because it does not necessarily entail discarding past ideals and parts of the collection; instead, new or modified ideals are added to old, yielding a complex set of goals that aspires to serve a widening set of constituencies. For example, although multiculturalism is now broadly embraced by museums and has led to collecting initiatives in formerly marginalized visual traditions, European art has hardly been ignored. In times past, museums were considered vital to the formation of artists and were therefore built alongside art schools; those affiliations are still largely intact even though ambitious young artists no longer copy the Old Masters as their predecessors once did. Today museums are more likely to tout their role in the cognitive development of children or their economic contribution to the local community. Art museums owe their survival and success to their ability to promote new, and not-so-new, “missions,” depending on current needs.

Lately, with rising strife around the world, mainstream art museums have stepped forward with a powerful new raison d'être: to foster global cooperation and understanding through a heightened awareness of shared interests and common values bodied forth in works of art. This message is at the core of the “Declaration on the Importance and Value of Universal Museums” (see Appendix), issued jointly in 2002 by nineteen leading museums “to stress the vital role they play in cultivating a better comprehension of different civilizations and in promoting respect between them,” according to Peter-Klaus Schuster, director of the State Museums of Berlin.4 Schuster and others argue that museums, because of the trust and respect they enjoy and their disinterested stance toward ideological contention in today's public sphere, are uniquely placed to promote cross-cultural exchange and smooth the path to social harmony and world peace—no small ambition.

Today the art museum's core functions—conservation, acquisition, scholarship, education—are increasingly directed toward, and justified by, this encompassing humanist purpose. This chapter charts the emergence of this museological ideal in the context of the utopian currents that have sustained art museums since their inception over two centuries ago. Apart from whatever historical interest a survey of museum ideals may have, it is vital to reckon with them if we are to comprehend the controversies and challenges museums face today. Ideals drive museums; they inspire the public to come, donors to give, and busy trustees and underpaid staff to serve. The chapters that make up the rest of this book examine aspects of museum policy and operation that are either means or obstacles to fulfilling a core mission. To understand art museums we must grasp the evolving relationships between ideals and mission, theory and practice, and perceived social commitments and overlapping constituencies.

Utopian Ideals and Real Politics

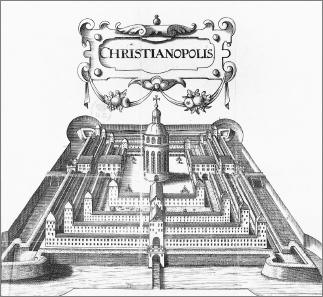

Before museums began appearing in the eighteenth century, they existed as notional spaces embodying ideals of collective learning and progress considered essential to a perfect society. Overlooked in the extensive literature on the origins of collecting and museums in early modern Europe is the appearance of museumlike structures in three famous utopian texts: Johann Valentin Andreae's Christianopolis (1619), Tomasso Campanella's City of the Sun (1623), and Sir Francis Bacon's New Atlantis (1627). Written by men of different nationalities, professions, and religions, the three texts signal the spread of a utopian museum ideal across Europe in step with the culture of collecting and curiosity. Andreae's model community of Christianopolis (fig. 3) is dominated by a college whose institutions represent universal knowledge: a library containing “the offspring of infinite minds,” a pharmacy amounting to “a compendium of all nature,” a natural history museum whose walls depict “the whole of natural history,” and so on.5 In Campanella's City of the Sun, knowledge is found, not in dedicated buildings, but in inscriptions on the city's seven concentric walls, integrating learning into everyday activity. Bacon's ideal city on the island of Bensalem is built around a college, Salomon's House, “dedicated to the study of the…true nature of all things,” “[the] enlarging of the bounds of human empire,” and “the effecting of all things possible.”6 Much of the New Atlantis is given over to a detailed description of the college, its facilities, collections, and goals, as if it were the true subject of the text. That Bacon's utopian model was designed to inspire real-world parallels is suggested by one of his earlier texts, Gesta Grayorum (1594), in which a fictional counselor advises his prince on the contents of an ideal museum. To achieve “in small compass a model of universal nature,” the prince should assemble, together with a “most perfect and general library,” a “spacious, wonderful garden,” a zoo with “all rare beasts and…all rare birds,” and “a goodly huge cabinet, wherein whatsoever the hand of man by exquisite art or engine hath made rare in stuff, form, or motion; whatsoever singularity chance and the shuffle of things hath produced; whatsoever Nature hath wrought in things that want life and may be kept; shall be sorted and included.”7

3. Johann Valentin Andreae, Christianopolis. Engraving from his Reipublicae Christianopolitanae descriptio, 1619. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Réserve des Livres rare.

4. Sébastien Le Clerc, The Academy of Sciences and Fine Arts, 1699. Etching, 24.8 × 38.4 cm. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1962 (62.598.300). Photo: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Bacon and Andreae were both adapting descriptions of ideal collections that had begun to circulate in the late sixteenth century, beginning with Samuel Quicchelberg's “universal theater” of 1565.8 What matters is the assumption that an elaborate institution for the collection, production, and dissemination of knowledge belonged at the heart of a perfect society. Inspired by the spread of collecting, museums and academies bodied forth in theoretical texts and images (fig. 4) became models for real-world institutions dedicated to serving the common good.9

From the Renaissance onward, the museum has been envisioned as a compendium of the world, a microcosm of the macrocosm, and a symbol of a harmonious, well-ordered society. But even as early imaginary museums provided a conceptual model for future academies and museums, they looked back to a common classical source of inspiration in the fabled mouseion at Alexandria (destroyed ca. AD 400) and the academies of Plato and Aristotle. Memories of those institutions haunted the early modern imagination, and the dream of recuperating and even surpassing lost knowledge underpinned all collecting and related study. Witness Andreae's traveler in the library at Christianopolis, “dumbfounded to find there very nearly everything that is by us believed to have been lost.”10 Ptolemy's “museum” at Alexandria, known only through scattered literary references hailing its vast collection of books and knowledge (“all the books in the inhabited world,” “the writings of all men,” and so on),11 established for later museums an ideal of universality all the more powerful because the collection itself no longer survived to reveal inevitable shortcomings.

5. Raphael, The School of Athens, ca. 1510–12. Fresco. Vatican Palace, Vatican State. Photo: Scala/Art Resource, New York.

Though knowledge progressed in the Renaissance beyond the written legacy of the ancients to encompass objects as well as books, antiquity nevertheless provided the visual means to represent the noble quest for knowledge. In paper projects and texts, museums and libraries took the form of ideal buildings modeled on classical temples, often lined with allegorical statues and busts of ancient philosophers. In Raphael's School of Athens (fig. 5) those philosophers are brought to life in a fittingly impressive space. One of four paintings decorating the Vatican library of Julius II (a collection that his contemporaries likened to the mouseion of Alexandria), it shows Plato and Aristotle engaged in metaphysical conversation at an imaginary gathering of history's great minds.12 The two men point, respectively, to heaven and to earth, which represent speculative and empirical philosophy, the combined source of causarum cognito (the knowledge of things), a phrase inscribed in the library's vault above. Though Julius's collection numbered only about five hundred books, the fresco illustrates the path to true understanding through the cumulative efforts of past, present, and future genius.

These early modern representations prepared the way for the full flowering of the utopian museum during the eighteenth century, when Enlightenment attempts to reduce the distance between an imaginary utopia and the actual world through philosophy and pragmatic reform lent urban planning and civic institutions a special prominence. In the words of Bronislaw Baczko, the Enlightenment propelled a shift from “cities in utopia to the utopia of the city, from power and government in the utopia to the power and government envisaged as the agent of the utopia and the executor of social dreams.”13 In the realm of utopian fiction, Sébastien Mercier's famous novel The Year 2440, published in 1771, is significant. Traveling into the future, Mercier's protagonist finds himself standing at the center of Paris, before a vast temple of knowledge that contains every specimen of nature and human culture, laid out with judgment and wisdom.14 Everywhere he turns he finds students and members of the public studying in an atmosphere of cooperation and freedom. Like earlier utopias, Mercier's fable contained recommendations for political and social reform. His futuristic museum was easily recognizable as the Louvre Palace, abandoned by the royal family for Versailles in the late seventeenth century and in need of a new purpose, and his fictional account read as a blueprint for government action.15 The French Revolution gave further impetus to utopian thinking about the Louvre. For Armand-Guy Kersaint, writing in 1792, the Louvre would “speak to all nations, transcend space, and triumph over time” by becoming a center of scholarship for the whole world that would accommodate “the reunion of all that nature and art have produced.”16 Revolutionary euphoria prompted the philosopher Condorcet, the great champion of human progress, to revive Bacon's vision of Atlantis, with its “vast edifices” consecrated to knowledge and its “crowd of researchers” working together for the good of mankind.17 What had been a dream in Bacon's day was, in Condorcet's view, close to being realized, thanks to the “rapid progress” made by the Enlightenment.

With the opening of the Louvre in 1793 the Revolution's particular sociopolitical ambitions superseded the general aspirations to universal knowledge found in earlier utopian tracts. The Revolution, in other words, appropriated the utopian potential of the museum and specified how it could be socially useful. Though the Louvre initially occupied only one wing of the palace, which was devoted solely to art (fig. 6), the museum was nonetheless infused with revolutionary optimism and purpose. It was inaugurated on August 10, 1793, the first anniversary of the founding of the republic, during a day-long Festival of Unity celebrating the republican ideals of liberty, equality, and fraternity. The key event planned for the festival was an elaborate parade though the streets of Paris that amounted to a symbolic mass appropriation of the French capital. “All individuals useful to society will be joined as one,” wrote the festival's mastermind, Jacques-Louis David. “[Y]ou will see the president of the executive committee in step with the blacksmith; the mayor with his sash beside the butcher and mason; the black African, who differs only in color, next to the white European.”18 Allegorical statues of liberty and national unity along the route replaced deposed monuments of former kings; on the site of Louis XVI's execution delegates from the eighty-six regional departments set fire to a symbolic pyre made of the “debris of feudalism.” The spirit of the festival continued inside the museum, where newly baptized citizens of the republic enjoyed free and equal access to treasures confiscated for the nation from the crown, the church, and émigré aristocrats in a royal palace turned palace of the people. Labels informed viewers who had owned the paintings prior to the Revolution, underscoring the power of liberation in the name of public instruction.

6. Hubert Robert, Grand Gallery of the Louvre between 1794–96, ca. 1794–96. Oil on canvas, 37 × 41 cm. Louvre Museum, Paris. Photo: Réunion des Musées Nationaux/Art Resource, New York.

At the same time, an orderly display of acknowledged masterpieces countered disturbing images of public executions and social turmoil by demonstrating the nation's commitment to universal cultural values. As a leading politician put it, the opening of the museum would quiet “political storms” and prove “to both the enemies as well as the friends of our Republic that the liberty we seek, founded on philosophic principles and a belief in progress, is not that of savages and barbarians.”19 The chronological sequence of pictures culminating in the French school affirmed the principle of progress on which the Revolution was founded and made clear that the future of art belonged to France. Finally, the Louvre served as a training ground for young artists following the dissolution of the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture in 1793. No longer constrained by a formal system of instruction, students were now free to choose their own masters from the canon of great art. Artists copying in the Grand Gallery became a common sight for more than a century beginning in the 1790s.

In the first decades of the nineteenth century, the multifaceted success of the Louvre—as a symbol of democratic access and responsible government, source of national and civic pride, and school for young artists and historians—proved irresistible to emerging nation-states in post-Napoleonic Europe. Newly formed nations shaped their cultural identity around their national patrimony, embodied in historical artifacts and works of art openly displayed in public museums.20 A nation exhibiting “classical” (Greco-Roman and Renaissance) art declared its adherence to civilized values and, by integrating homegrown artists, argued for including native traditions in the canon. Other countries followed the French example by using museums to instruct artists, artisans, scholars, and the public at large. Between 1800 and 1860, important museums modeled on the Louvre opened in Brussels (Royal Museum, 1803), Amsterdam (Rijksmuseum, 1808), Rome (Vatican Pinacotheca, 1816), Venice (Accademia, 1817), Milan (Brera, 1818), Munich (Glyptothek, 1815; Pinakothek, 1836), Madrid (Prado, 1819), London (National Gallery, 1824; British Museum, rebuilt 1823–47), Berlin (Altes Museum, 1830), and St. Petersburg (Hermitage, 1852). By the end of the century the museum movement had spread from Europe to North and South America, Asia, and Australia, so that virtually every capital and major city in the advanced world (and its colonies) could boast a public art museum of its own.

Useful Recreation

The belief, emanating from German philosophy, in the uplifting and harmonizing power of art further informed the spread of museum culture in the early nineteenth century. Art had long served to inspire religious devotion and loyalty to earthly rulers, but the new aesthetics of Kant and Schiller insisted that the beauty and autonomy of art could nourish the spirit of the individual subject by lifting consciousness above the contingent realities of the material world without letting it become lost in abstractions. “Through Beauty,” wrote Schiller in On the Aesthetic Education of Man (1795), “the sensuous man is led to form and to thought; through Beauty, the spiritual man is brought back to matter and restored to the world of sense.”21 By appealing to the sensibility of individual viewers, art exhibited in public museums could improve and harmonize society as a whole.

Though the belief in art's restorative powers dates back to antiquity, when paintings and sculptures decorated country retreats outside Rome and constituted an appropriate subject of leisurely conversation, it took on new urgency during the Industrial Revolution, when the pace of modern life quickened. Witness William Hazlitt's reflections on a visit to the London collection of John Julius Angerstein (fig. 7) in the early 1820s:

Art, lovely Art! “Balm of hurt minds, chief nourisher in life's feast, great Nature's second course!” Time's treasurer, the unsullied mirror of the mind of man!…A Collection of this sort…is a cure…for low thoughted cares and uneasy passions. We are transported to another sphere…. We breathe the empyrean air…and seem identified with the permanent form of things. The business of the world at large, and of its pleasures, appear[s] like a vanity and an impertinence. What signify the hubbub, the shifting scenery, the folly, the idle fashions without, when compared to the solitude, the silence of speaking looks, the unfading forms within.22

Facing mass immigration and unrest in newly industrialized cities, governments across Europe embarked on a course of museum building in the hope that the benefits described by Hazlitt could be extended to the population at large. Soon after Hazlitt's visit, the Angerstein collection in London became the nucleus of the new National Gallery (founded 1824).

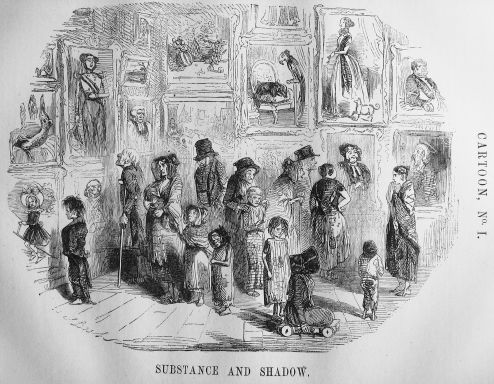

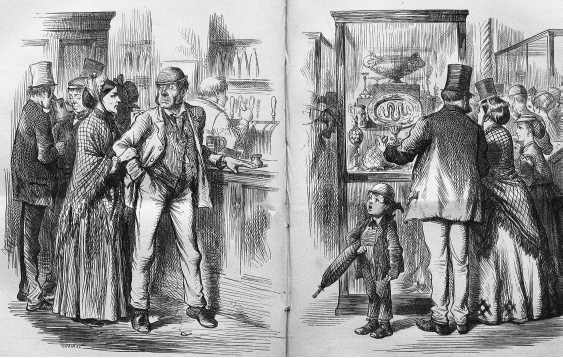

Urban riots in the early 1830s prompted Sir Robert Peel, a leading politician and the founder of the London police, to recommend the expansion and rebuilding of the gallery: “In the present times of political excitement, the exacerbation of angry and unsocial feelings might be softened by the effects which the fine arts had ever produced on the minds of man…. The rich might have their own pictures, but those who had to obtain their bread by their labour, could not hope for much enjoyment…. The erection of [the new National Gallery] would not only contribute to the cultivation of the arts, but also to the cementing of the bonds of union between the richer and poorer orders of state.”23 Government inquiries in the 1830s, 1840s, and 1850s confirmed the popularity of the new gallery (its attendance ran as high at ten thousand visitors a day) among a broad public. The satirical magazine Punch (fig. 8), however, was not convinced that Old Master paintings were what the people needed. It noted that the government seemed to have decided that since it “cannot afford to give hungry nakedness the substance which it covets, at least it shall have the shadow. The poor ask for bread, and the philanthropy of the state accords them—an exhibition.”24 But London's museum boosters were undeterred, insisting on the palliative effects of museum-going on the working multitudes. In the late 1840s, Dickens's friend Charles Kingsley had this to say in favor of art museums: “Picture-galleries should be the townsman's paradise of refreshment…. There, in the space of a single room, the townsman may take his country walk—a walk beneath mountain peaks, blushing sunsets, with broad woodlands spreading out below it…and his hard-worn heart wanders out free, beyond the grim city-world of stone and iron, smoky chimneys, and roaring wheels, into the world of beautiful things.”25 Museum men like Sir Henry Cole, founder of the South Kensington Museum, joined forces with temperance leaders to have museums open on Sundays and weekday evenings in order to give the working classes a wholesome recreational alternative to procreation and the pub (fig. 9). “Let the working man get his refreshment there in company with his wife and children,” Cole told an audience in 1875; “don't leave him to find his recreation in bed first, and in the public house afterwards.”26

7. Frederick Mackenzie, The Original National Gallery at J.J. Angerstein's House, Pall Mall, London, ca. 1834. Watercolor, 46.7 × 62.2 cm. Photo: Victoria and Albert Museum, London/Art Resource, New York.

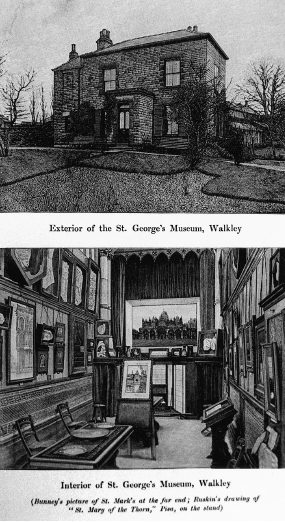

Museum historians and critics, inspired by the institutional critique of Michel Foucault, have argued that museums in the Victorian period, besides offering innocent diversion for the masses, contributed to what Foucault termed the “disciplinary technology” of the modern state, whose purpose was to produce “docile,” ordered, and patriotic citizens.27 This was clearly the case. For John Ruskin museums offered “an example of perfect order and perfect elegance…to the disorderly and rude populace.”28 Henry Cole believed they would “teach the young child to respect property and behave gently.”29 The chairman of the Art Union of London viewed museum visits by the workingman as productive on both social and economic levels: “Once refreshed he can return to work a productive member of society.”30 The first president of New York's Metropolitan Museum, Luigi di Cesnola, listed museums, with “the college, the seminary, the hospital, and the asylum,” as “blessings” that “benefit the community at large.”31 But museums, unlike asylums and prisons, Foucault's chief examples of disciplinary institutions, made art accessible to those whose lives were otherwise constrained by menial labor, poverty, and crowded tenements. What they offered was more “shadow” than “substance,” to be sure, but within modern capitalist society they were as much a source of release and respite as a source of discipline. Surviving the failure of his antimodern utopian community, the Guild of St. George, Ruskin created a museum (1875; fig. 10) that aspired to counter the relentless and dehumanizing forces of modern industry. Giving thought to where it could do most good, he sited his museum on a hilltop above the steel mills of Sheffield, a city portrayed by a journalist as “the black heart of the grimy kingdom of industry” and as a hotbed of “trades-union terrorism.”32 Visitors easily grasped Ruskin's purpose, describing his museum as a “refreshing and useful respite from daily toil” and “an ever-fresh oasis of art and culture amidst the barrenness and gloom of an English manufacturing district.”33 Housed in a modest cottage and run by Henry Swan, a workingman made good, Ruskin's museum was planned as a model for other industrial towns. Equally concerned about the effects of the new industrial order, Ruskin's contemporary Matthew Arnold advocated the softening effects of culture, which he famously defined as “the best that has been thought and said.” In his much-read book Culture and Anarchy (1869), Arnold stressed the value of embracing “all our fellow men”—not least the “the raw and unkindled masses”—in the “sweetness and light” of high culture in order to unify society and prevent anarchy. The purpose of culture and its broad dissemination was to bring about the “general expansion of the human family” and to “leave the world better and happier than we found it.”34 Arnold never mentioned museums specifically, but his theories greatly influenced museum culture on both sides of the Atlantic in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

8. “Substance and Shadow.” From Punch, July 8, 1843.

9. Sir John Tenniel, “The Sunday Question: The Public-House, or, the House for the Public?” From Punch, April 17, 1869.

Meanwhile the direct needs of industry and manufacturing led to the creation of a new type of museum devoted to the applied and decorative arts. The South Kensington Museum (fig. 11) opened in London in 1857 near the site of the immensely popular Great Exhibition of 1851 with the intention of making permanent the exhibition's benefits to the British economy and the general public.35 By displaying domestic goods (metalwork, pottery, textiles, glass, and so on) rather than rare and costly paintings, South Kensington appealed to the everyday tastes of the public at large even as it provided study samples for manufacturers and aspiring students of design. In other words, the museum was intended to be both popular respite and industrial resource; and in keeping with the positivist spirit of nineteenth-century capitalism, its “profits” would be both concrete and quantifiable. Improved industrial design could be measured in increased sales and exports of British goods, while improved morality among the laboring classes, a by-product of innocent recreation, would be reflected in decreasing rates of childbirth, drunkenness, and crime.

South Kensington's blend of popular appeal, economic relevance, and social reform made it a quintessentially utilitarian product of the Victorian era. Encouraged by the museum's success, founder Henry Cole took his message on the road in the hope that “every centre of 10,000 people will have its museum” and that thereby “the taste of England will revive [among] all classes of the people.”36 Just as medieval England once “had its churches far and wide,” so the modern world would have its engines of progress and social uplift in the form of museums.37 Surveying Britain in the late 1880s, Thomas Greenwood found that Cole's example had been widely imitated. Greenwood's book Museums and Art Galleries (1888), among the first texts devoted to the subject, documented the extraordinary spread of museum culture across Britain's industrial heartland. New museums in Sheffield, Preston, Liverpool, Manchester, and Birmingham, the fruit of civic enlightenment and private philanthropy, gave particular cause for optimism. “Unmistakably useful as are a large number of Museums and Art Galleries,” Greenwood remarked, “we have, as yet, only touched on the fringe of their possible usefulness.”38

10. St. George's Museum, Sheffield, Yorkshire. From The Works of John Ruskin, ed. E. T. Cook and A. Wedderburn, vol. 30 (London: George Allen, 1907).

11. South Kensington Museum, original “Brompton Boilers” building. Engraving from Illustrated Times, June 27, 1857.

Despite its great promise and influence on both sides of the Atlantic, the philosophy of the South Kensington Museum fell into disfavor toward the end of the century owing to its evident failure to inspire better-designed products or alleviate the demeaning nature of mechanized labor.39 Over the years few manufacturers had sent their designers to study at the museum, prompting the painter Hubert von Herkomer to declare that “William Morris had done more in a few years to promote true decorative art than had been done by South Kensington during the whole of its existence.”40 The design school attached to the museum had similarly fallen short of its goals, devolving into a conventional but second-rate art academy for aspiring artists not good enough to be admitted elsewhere. At the same time, the museum's West End location had deterred visits from the artisan class it was designed to serve; in his survey, Thomas Greenwood observed that the museum was patronized mostly by the residents of the well-to-do borough.41 In 1899 South Kensington was renamed the Victoria and Albert Museum and acquired a new direction, shifting its focus to collecting fine and rare objects and serving an antiquarian public. When the new Musée des Arts Décoratifs opened in Paris in 1905, contemporaries viewed it as an institution forty years too late in coming. “Are we to suppose, as we did in 1865,” wrote Paul Vitry, “that such collections of old and new objects will lift the imagination of artists and in themselves produce more bountiful and varied creations? We no longer believe that to be so.”42

The collapse of utilitarian ideals was felt across a broad spectrum of museum types in the late nineteenth century. Just as the applied arts museum was ill suited to the practical needs of industry, so, as Steven Conn has argued, the static, object-based epistemology of early science and anthropology museums proved incapable of evolving in step with the shift in the natural and human sciences toward theory, experimentation, and contextual analysis.43 The focus of knowledge production in those disciplines shifted to universities. The sudden obsolescence of the utilitarian Victorian museum even figures in the era's famous dystopian novel, H.G. Wells's Time Machine (1895), in which the time traveler stumbles across the abandoned, object-filled ruins of the once magnificent Palace of the Green Porcelain (a reference to South Kensington?) in a postapocalyptic London landscape.44

On the eve of the Great Exhibition, Prince Albert had declared that the display of manufactured goods from around the world would bring about the “union of the human race” through improved manufacturing, consumption, and international trade.45 A half-century later, the expansion of industry and trade was instead blamed for the rise of materialism, international competition, and strife. In Culture and Anarchy Matthew Arnold had warned against a creeping materialism that threatened society from within. The “unfettered pursuit” of wealth had produced both “masses of sunken people” that society could ill afford to leave behind and a crass new middle class blinkered by a love of money and material goods. Arnold believed that “the temptation to get quickly rich and to cut a figure in the world” had become a corrosive force in advanced industrial society. The purpose of high culture, therefore, was to reduce the materialism of the bourgeoisie even as it civilized the poor.46 Arnold's insistence that culture was as important to the middle classes as it was to the poor would have enormous implications for art museums in the twentieth century.

South Kensington's explicit encouragement of industry and consumption ran counter to antimaterial aspirations, but at the same time the world of high art itself was showing disturbing signs of overproduction and conspicuous consumption. Congested exhibitions (like the Salon in Paris), thriving art dealerships, and record prices for Old Master paintings at turn-of-the-century auctions signaled that high art had become a market commodity and source of social distinction. For the German critic and historian Julius Meier-Graefe, writing in 1904, the art exhibition, “an institution of a thoroughly bourgeois nature, due to the senseless immensity of the artistic output…may be considered the most important artistic medium of our age,” feeding the “mania for hoarding” that afflicts “the famous collectors of Paris, London, and America” like a “disease.”47 Meier-Graefe argued that art had long ago lost its purpose, becoming no more than a bourgeois trifle to “distract tired people after a day's work.”48 Commenting on New York's beau monde in the same year, Henry James famously remarked: “[T]here was money in the air, ever so much money…. And the money was to be all for the most exquisite things.”49 Five years earlier, Thorstein Veblen had published The Theory of the Leisure Class (1899), a blistering analysis of the indulgence of the rich.

The Social Utility of High Art

The challenge for art museums and collectors entering the twentieth century, then, was to chart a course that simultaneously eschewed claims to practical relevance and avoided the taint of materialism and bourgeois superficiality. Collectors did this by making well-publicized and seemingly selfless donations to local museums or by creating museums of their own. The astronomical sums paid for works of art in the early 1900s by the likes of Isabella Stewart Gardner, Henry Clay Frick, Henry Huntington, and J. P. Morgan were justified by the promise that those objects would soon be returned to the public realm and made accessible to all (the “house” museums of all four collectors date from that time).50 And museums in turn attempted to forestall complaints of useless excess by rededicating themselves to aesthetic idealism and insisting on the social value of providing nonmaterial nourishment to rich and poor alike.

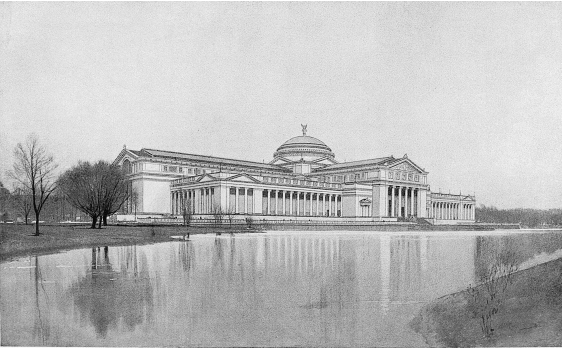

In Europe, well-established public art galleries needed only to refine their operation (principally culling overstocked collections, as we shall see in chapter 3), but in the United States the situation required a more significant redefinition of purpose. In a country looking to expand economically and eager to prove itself civilized, both European museum models—the utilitarian and the aesthetic—had enjoyed great appeal.51 The pioneering museums of Boston (founded 1870), New York (1870), Philadelphia (1876), and Cincinnati (1881), together with the great exhibitions at Philadelphia (1876), Chicago (1893), and St. Louis (1904), attempted to fuse the practical impetus of South Kensington with the aesthetic idealism of the Louvre, London's National Gallery, and the Berlin Museum. For example, a visitor to Philadelphia's Centennial Exposition in 1876 noted its “union of two great elements of civilization—Industry, the mere mechanical, manual labor, and Art, the expression of something not taught by nature, the mere conception of which raises man above the level of savagery.”52 Cesnola's Address on the Practical Value of the American Museum stresses the dual mission of museums, to serve as “a resource whence artisanship and handicraft…may beautify our dwellings” and as an exhibition of “the riper fruits of civilization.”53 By the time of Chicago's Columbian Exposition, however, we begin to sense a new role for art in the emerging socioeconomic order. 54 Removed from the din and bustle of new machines and myriad consumer products at the “White City” fairgrounds stood a classical temple dedicated to the fine arts (fig. 12). In the exposition's utopian vision of a prosperous, technology-driven future, the temple by the lake offered respite and the stabilizing comfort of transcendent values.

12. Charles B. Atwood, Fine Arts Palace, Chicago Columbian Exposition, 1893. From Ripley Hitchcock, The Art of the World (New York: D. Appleton, 1895).

In the years on either side of 1900, a renewed commitment to aesthetic idealism banished the remains of Victorian utilitarianism and set art museums on a path they still follow. The Metropolitan closed its technical school in 1894, and a decade later J. P. Morgan took over as head of the trustees and imported the English artist and critic Roger Fry to steer the museum toward the fine arts.55 Fry determined to collect only “exceptional and spectacular pieces,” a guideline that has described the Met's buying policy ever since.56 At Boston's Museum of Fine Arts, like-minded aesthetes Matthew Prichard and Benjamin Gilman fought to rid the museum of its utilitarian ethos and replace it with a doctrine of high aestheticism. Plaster casts, copies, and the applied arts gave way to original high art representing what Gilman, quoting Arnold, described as the visual equivalent of “the best that has been thought and said in the world.”57 Gilman insisted that “neither in scope nor in value is the purpose of an art museum a pedagogic one,”58 by which he meant that the worth of an art museum was to be measured not in terms of practical efficiency, as it had been at South Kensington, but in terms of the salutary effects of beauty and human perfection on each and every visitor multiplied across society. Museums “are not now asking how they may aid technical workers,” he wrote, but “how they may help to give all men a share in the life of the imagination.”59 The Boston museum was rebuilt at a healthy remove from the city center to signal the shift in purpose (see chapter 2), and a new program of popular instruction stressing aesthetic appreciation was put into operation. When the industrialist Andrew Carnegie created the Carnegie Institute in North America's equivalent to Sheffield, respite, not practical instruction, was uppermost in his mind. “Mine be it to have contributed to the enlightenment and the joys of the mind, to the things of the spirit, to all that tends to bring into the lives of the toilers of Pittsburgh sweetness and light,” he said (quoting Arnold) in his dedication speech in 1895.60 Philanthropic support of high art museums had particular appeal for captains of trade and industry like Carnegie and Morgan, who saw the gift of art as transforming their wealth into aesthetic and spiritual uplift for the people.

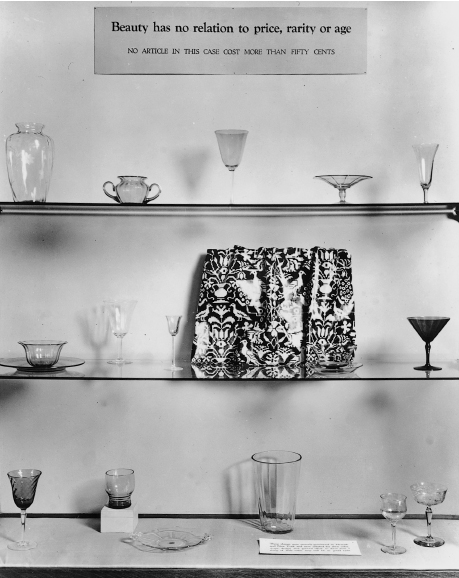

Utilitarianism did not vanish altogether, however. It retained a forceful advocate in the person of John Cotton Dana, director of the Newark Museum. Through the first decades of the twentieth century, Dana and Benjamin Gilman sparred over the direction of the museum, with Dana shaping his own institution in opposition to what he termed “gazing museums” like the Met and MFA, whose main function, as he saw it, was to satisfy the “culture fetishes” of the privileged classes.61 Influenced by Veblen's Theory of the Leisure Class, Dana saw the collecting of art and patronage of art museums as exemplifying the “conspicuous waste of the rich” and providing “another obvious method of distinguishing their life from that of the common people.”62 The air of wealth and hushed reverence, combined with the “splendid isolation of a distant park,” made the new art museums (such as those in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia, all built in new parks) the antithesis of the useful, community-based institution Dana had dedicated his life to creating. Where Gilman advocated silence and separation as necessary conditions for contemplation and “respite” from which museum-goers emerged “strengthened for that from which it has brought relief,”63 Dana insisted that museums serve their constituents through active involvement in their everyday lives. Instead of acquiring costly European works of art, whose “utility [was] vastly over-rated” and whose cost was “out of proportion to their value,”64 Dana thought the modern museum should be grounded in the community and should respond to its specific needs. In place of “undue reverence for oil paint,” museums should showcase “objects which have quite a direct bearing on the daily life of those who support it…from shoes to sign posts and from table knives to hat pins.”65 Dana argued that department stores were as useful as museums, and he staged provocative displays of “beautiful” everyday objects available for less than fifty cents at the local dime store (fig. 13).

13. Inexpensive Objects exhibition, Newark Museum, 1929. Photo courtesy of the Newark Museum.

Dana's writings are being rediscovered and recirculated today by both latter-day disciples in the museum and outside critics, but his impact on art museum practice in his own time was limited.66 Though Gilman's name has also been largely forgotten, his advocacy of respite and the restorative power of beauty proved far more influential. Gilman answered Dana's rejection of art's limited utility by insisting on the usefulness of the useless: though art might not “bring anything else worth while to pass,” it had the power to provide pleasure, virtue, and knowledge.67 Gilman's model proved more influential in part because it provided a social justification for the collecting and philanthropy of the rich, but it also satisfied middle-class desires in a way Dana's utilitarianism did not. While Dana spoke to everyday material needs, Gilman preached transcendence of the mundane, an aspiration that the leisured classes could more easily afford to pursue. Gilman cared greatly about extending the art museum's franchise to the poor, and designed education programs to that end, but he knew it would not happen overnight; in the meantime his sermons on beauty and transcendence found an eager audience among the already educated, who have ever since provided the art museum's loyal base of support. The eager participation of the bourgeois public in search of spiritual uplift and escape overtook the top-down social engineering ideals of the museum's early sponsors.

Art Museums and War

The art museum's standing as an oasis of high culture in a brutalized, materialistic world increased greatly during and after World War I. Many blamed the war on rising economic competition and its catastrophic death toll on improved technological efficiency. Addressing students at Yale University in the first year of the Great War, the architect Ralph Adams Cram insisted that because art was “the revelation of the human soul, not a product of industrialism,” it stood above “the economic and industrial Armageddon that surges over the stricken field of contemporary life.”68 Charles Hutchinson, president of the Art Institute of Chicago, inaugurated the Cleveland Art Museum in 1916 with a speech that hailed art as an antidote to the materialism that had fueled the war and as the means to “increase the happiness of future generations.” Fiercely rejecting the doctrine of “art for art's sake,” he insisted that art's utility had never been more apparent: “Art for art's sake is a selfish and erroneous doctrine, unworthy of those who present it. Art for humanity and service of art for those who live and work and strive in a humdrum world is the true doctrine and one that every art museum should cherish.”69 A year later, the critic Mariana van Rensselaer wrote that the horrors of war raised the need “to cultivate the idealistic side of human nature” and “to combat the ambitious materialism, the self-seeking worship of ‘practical efficiency’ which is so largely to blame for the agony of Europe and which threatens the happiness of America also.”70 She held out hope that museums could demonstrate that “material things are not all in all” and “that art, that beauty is not a mere ornament of existence but a prime necessity of the eye and the soul.”71

Following the war the art museum's emerging humanitarian charge broadened to include greater international cooperation and understanding. Colonial expansion across the globe, coupled with world's fairs and avant-garde initiatives in the arts (for example, Japonisme and the influence of African masks), encouraged growing interest in world art traditions, which reached the public through museums and exhibitions. Roger Fry, an early enthusiast of African and modern art, had insisted in his influential book Vision and Design (1920) that an essential part of what was experienced by beholders of a work of art was “sympathy with the man” who brought it into being: “[W]e feel that he has expressed something which was latent in us all the time, but which we never realized, that he has revealed us to ourselves in revealing himself.”72 Ernest Fenollosa, the distinguished scholar of Asian art, wrote: “We are approaching the time when the art work of all the world of man may be looked upon as one, as infinite variations of a single kind of mental and social effort…. A universal scheme or logic of art unfolds, which as easily subsumes all forms of Asiatic and of savage art…as it does accepted European schools.”73 Our ability and desire to feel in works of art an immediate and profound connectedness with people and communities separated by time and cultural difference made art uniquely suited to act as a bridge between peoples. Art is “a kind of universal solvent, a final common denominator,” wrote Cram, “and before our eyes the baffling chaos of chronicles, records, and historic facts open[s] out into order and simplicity.”74 While art constituted a unique record of a people and its beliefs, it was also a vehicle for mutual understanding, and on both scores it had to be safeguarded for the good of humanity. Writing at the end of the war, Benjamin Gilman said that “a penetration of the spirit of other peoples, a recognition of their ideals, and as far as may be a sharing of them” had become “the duty of an international culture” that art museums could help to fulfill.75

Just as art museums were assuming a new diplomatic responsibility, forty-one nations ratified the Hague Convention, which included (article 27) the first international accord on the protection of art during war: “In sieges and bombardments all necessary steps must be taken to spare, as far as possible, buildings dedicated to religion, art, science, or charitable purposes, historic monuments.”76 The preservation of artistic heritage took on great importance during World War I as a result of the Hague agreement. For the first time efforts were made to spare cultural sites, including museums, and at the same time to document for propaganda purposes damage inflicted by the enemy. Amid the carnage of a horrific war, both sides claimed a love of art as if seeking absolution for their sins against humanity. As the aggressors, the Germans tried especially hard to trumpet their respect and responsibility for art. Despite inflicting terrible damage on French and Belgian monuments, including Reims Cathedral, they insisted that the “culture of art and war” were “the most extreme opponents conceivable, like two poles which flee from one another just as the principles of preservation and destruction.”77 Puncturing German rhetoric, the French mounted an exhibition in Paris in 1916 of battle-scarred works of art for all to see. The inspector general of French museums, Arsène Alexandre, published a catalog of lost monuments—“many of which were cherished by the whole world”—to demonstrate to posterity that the Germans were “the enemies of humanity.”78 But looking to the future, Alexandre also hoped his book would inspire a greater respect for civilization and “association among all the human races.”79 Alexandre declared that even greater cooperation and a deeper appeal to civilized values were needed in view of the failure of the Hague Convention to prevent the devastation of modern war: “It was not in the name of the Hague Convention, nor the Geneva Convention, that the scholars and artists of France and the civilized world cried in protest [against the destruction of art]…. The laws in whose name one protested have no date…. [T]he laws of beauty, goodness, and justice are not written in perishable words but in the hearts of individuals and the consciences of nations.”80

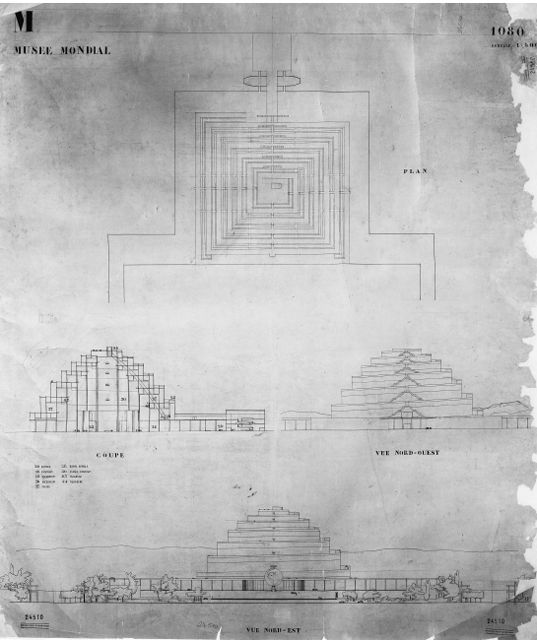

With such sentiments in mind, the League of Nations was formed in the decade following the war. In 1926 the League's International Committee on Intellectual Cooperation created the International Museums Office (forerunner of the International Council on Museums, or ICOM) and two years later sponsored an international congress of popular arts in Prague. Because the popular arts manifested “the deepest currents of civilization,”81 as the art historian and International Committee member Henri Focillon put it, they could “characterize in a direct and immediate manner a people, region, and locality” and thus, when exhibited together, could demonstrate “the similitude and analogies that link the members of the large human family.”82 One of the organizers of the Prague exhibition wrote: “From the assembly of these documents emerges a human aesthetic—one might even say a ‘human ethic’—that rises above the specificity of national aesthetics. Right there, at the tip of one's fingers, one has a common ground for all peoples and all times.”83 Conceived by Focillon, the event was organized by Jules Destrée, first director of the International Museums Office, who fervently believed that art was the “most universal instrument of reciprocal understanding among peoples” and “one of the most effective means of establishing a solidarity of heart and mind in a world dislocated by the war.”84 The League of Nations attempted to institutionalize global understanding a year after the Prague exhibition through the Mundaneum project, which was conceived as a “[c]enter for intellectual union, liaison, cooperation and coordination[;]…[a] synthetic expression of universal life and comparative civilization; a symbol of the intellectual Unity of the World and Humanity; [a]n image of the Community of Nations[;]…[a] means of making different peoples known to each other and leading them into collaboration; [a]n Emporium of works of the spirit…. The desire is: That at one point on the Globe, the image and total signification of the World may be seen and understood.”85 The symbolic heart of the unrealized Mundaneum complex was Le Corbusier's “World Museum” (fig. 14), designed as a square ziggurat, ancient and fundamental in form, to house “all the world's civilizations” laid out chronologically from prehistoric times to the present. (The simultaneous discovery of prehistoric painted caves in France and Spain gave art added weight as a transcendent human document.) Against the backdrop of recent turmoil, the World Museum would allow visitors to behold “the unchanging soul of humanity in the form of artworks which are, for us, immortal…, unadulterated witnesses.”86 Across the Atlantic at the same time, DeWitt Parker expressed similar ideas in a lecture at the Metropolitan Museum:

Art is the best instrument of culture. For art is man's considered dream; experience remodeled into an image of desire and prepared for communication…. Art puts us into touch with the desires of other classes, races, nations. Through art we not only know what these desires are, but we are compelled to sympathize with them; for the dream is embodied in such a way as to make us dream it as if it were our own. The barrier between one dream and the dream of another is overcome. The understanding of other nations, which by any other path would be long and difficult, is immediate through art…. Even as love creates an instant bond between diverse man and woman, so does art between alien cultures.87

Though art and culture had failed to prevent the Second World War, they were called upon to soften its effects and remind people of what was worth fighting for. During the darkest days of the war, London's National Gallery symbolized the endurance of a people—and of civilization—by hosting daily lunchtime concerts under the leadership of Dame Myra Hess (fig. 15).88 “This was what we had all been waiting for—an assertion of eternal values,” the gallery's director, Kenneth Clark, later recalled.89 The evacuation of London's museums as a precaution against German bombing only prompted a heightened sense of art's soothing power. “Art is one of the simplest and most effective ways of taking a man ‘out of himself’ and making him forget the trials and troubles of ordinary life, and especially life in war-time,” wrote J. B. Manson, a former director of the Tate Gallery in 1940, regretting the sudden termination of normal museum functions.90 Two years later a letter to the London Times pleaded for access to the nation's treasures notwithstanding terrible bomb damage to the capital: “Because London's face is scarred and bruised these days, we need more than ever to see beautiful things…. Music lovers are not denied their Beethoven, but picture lovers are denied their Rembrandts just at a time when such beauty is most potent for good.”91 Soon thereafter the National Gallery initiated its highly popular “Picture of the Month” exhibitions, featuring a masterpiece brought back from safekeeping in the mines of Wales. The gallery invited public input on the selection of pictures and duly received a large number of suggestions. “These make it perfectly clear,” wrote Kenneth Clark, “that people do not want to see Dutch painting or realistic painting of any kind: no doubt at the present time they are anxious to contemplate a nobler order of humanity.”92 The first three shows featured Titian's Noli Me Tangere, El Greco's Purification of the Temple, and Botticelli's Mystic Nativity. Thereafter the selection became more eclectic and included some of the gallery's most beloved works, including Constable's Hay Wain, Velázquez's Rokeby Venus, Bellini's The Doge, and a Rembrandt self-portrait.

14. Le Corbusier, plan of the Musée Mondial, 1929. Drawing.

© 2006 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris/FLC.

During the war years Frank Lloyd Wright began designing his Guggenheim Museum (1943–59; fig. 16) as a monument to the transfiguring power of art in the modern world. The museum's founder, Solomon Guggenheim, guided by his adviser Hilla Rebay, believed that his collection of “nonobjective” (abstract) art embodied a universal language that could lead to a “brotherhood of mankind” and a “more rhythmic creative life and…peace.”93 As Rebay put it to Wright, the new art would usher in a “bright millennium of cooperation and spirituality,…understanding and consideration of others…. Educating humanity to respect and appreciate spiritual worth will unite nations more firmly than any league of nations.” “Educating everyone…may seem to be Utopia, but Utopias come true.”94 As Neil Levine has written, Wright responded to Rebay's and Guggenheim's belief that “art's utopian social values were primary” by creating what he called an “optimistic ziggurat” designed to foster communication and community under a magnificent dome of light.

15. Dame Myra Hess in concert at the National Gallery, London, 1939. From Museums Journal, October 1939.

After the war, museums and exhibitions were asked to help rebuild the human spirit. A 1946 article in Museum News declared: “The champion of man turns out to be man, and it is in the arts that we find the mirror of human dignity, a microcosm both of order and serenity, of vitality and valor.”95 At the first meeting of the American Association of Museums after the war, the poet and Librarian of Congress Archibald MacLeish delivered a paean to the power of museums to create a better world. Rapid advances in destructive technology made ineffectual any “physical defenses against the weapons of warfare,” he wrote. “There are only the defenses of the human spirit.”

The work to be done is the work of building in men's minds the image of the world which now exists in fact outside their minds—the whole and single world of which all men are citizens together…. What is required now is…communication between mankind and man; an agreement that we are, and must conduct ourselves as though we were, one kind, one people, dwellers on one earth…. The world is not an archipelago of islands of humanity divided from each other by distance and by language and by habit, but one land, one whole, one earth…. It is precisely to their power to communicate such recognitions that the great cultural institutions of our civilization owe their influence…. The great libraries and the great galleries…demonstrate to anyone with ears to pierce their silence that the extraordinary characteristic of human cultures is their human likeness.96

16. Frank Lloyd Wright, Guggenheim Museum, New York, 1959.

MacLeish understood that “the conception of the gallery or the museum as the glass in which the total community of the human spirit can best be seen” could too easily become a “banal slogan of rhetorical idealism,” but he insisted that “there never was a time in human history when it was more essential to take [the] simple meaning [of that idea] and to understand it and to act.”97

Research is still needed to discover in what ways art museums responded to MacLeish's call to action. How typical was the “Wings around the World” program initiated in 1948 by the Minneapolis Institute of Art to teach high school students “the background, ideas, and cultures of the many peoples who have contributed to contemporary civilization” and “illustrate through works of art, the sociological, economic, political, and aesthetic ideals which constitute the heritage of all religious and racial groups”?98 The most famous exhibition of postwar humanism was The Family of Man, which opened at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1955 and subsequently toured the world in various formats for a decade (fig. 17). When the tour came to an end, it had been seen by some eight million people in thirty-seven countries; the book accompanying the exhibition is still in print and has sold over three million copies.99 The Family of Man used contemporary photographs, many by unknown photographers, to enhance its immediacy and relevance and featured images of ordinary people from around the globe engaged in universal human activities: working and at play, laughing and crying, giving birth and dying. The wall panel at the entrance read:

There is only one man in the world / and his name is All Men.

There is only one woman in the world / and her name is All Women.

There is only one child in the world / and the child's name is All Children.

A camera testament, a drama of the grand canyon of humanity, and epic woven of fun, mystery and holiness—here is the Family of Man!100

The Family of Man was the last of a series of photomontage exhibitions curated at MoMA by Edward Steichen and dating back to World War II (Road to Victory, Power in the Pacific, Airways to Peace), but here seductive display strategies honed in the service of war were mobilized to support the common cause of life and peace. For Steichen, the exhibition was conceived “as a mirror of the universal elements and emotions in the everydayness of life—as a mirror of the essential oneness of mankind throughout the world”101 and thus represented “an antidote to the horror we have been fed from day to day for a number of years.”102 As a widely circulated photo exhibition and illustrated book, The Family of Man realized André Malraux's dream that museums and photography would advance the communication of universal values. In his famous postwar book Museum without Walls (1951, translated into English 1953), Malraux hailed the ability of the photograph and the museum to minimize differences of scale, media, and culture in the interests of expressing instead “the mysterious unity of works of art” and their essential value as symbols of “a fundamental relationship between man and the cosmos.”103

17. Installation view of The Family of Man exhibition, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1955. Photo: Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Art Resource, New York.

During the Cold War decade of the 1950s, art museums in the West supplemented the rhetoric of universal humanism by promoting art as the embodiment of freedom and creativity. When the Guggenheim opened in 1959, it was described by President Eisenhower (in a letter read aloud at the opening) as “a symbol of our free society, which welcomes new expressions of the creative spirit of man.”104 During that decade, the abstract tradition celebrated by the Guggenheim gained legitimacy as the expression of bold individualism and the antithesis of the censorship and social-realist propaganda of fascist and communist regimes.105 Moreover, Western museums countered the heavy-handed ideological use of text and interpretation in Soviet and Nazi museums and art exhibitions before the war (notably the 1937 Degenerate Art show in Munich, see chapter 3) by minimizing wall labels and interpretation and allowing works of art to “speak for themselves.” A yearning for freedom from all ideological systems became the prevailing ideology of the postwar generation in the West, as we see, for example, in a passage from Walter Pach's 1948 book The Art Museum in America: “Today we must leave every person free to form his own convictions, and the way to do that is to concentrate on the collections themselves, allowing the masters and the schools to say their say, independent of interpretations by educators.”106 Privileging aesthetics over ideology or contextual analysis had long been the policy of MoMA under Alfred Barr, whose tenure at the museum stretched from 1929 to 1967 (and who served as director from 1929 to 1943). From the 1930s, MoMA's pioneering exhibitions and catalogs on modern art “relieved formal analysis of any interpretive responsibility by conveying…only what could be seen,” in the words of Barr's recent biographer.107 Barr's successor at MoMA, William Rubin, was equally committed to a “wordless history of art” that allowed “the esthetic values of the pictures, their analogies, cross-relationships and historical filiations…to tell [their] own story.”108 In the 1950s and 1960s MoMA emerged as both the showcase for advanced Western art and, as we shall see in subsequent chapters, the model for modern museology.

The Return of Social Relevance

Nevertheless, the easy spread of humanist rhetoric in the West, carried along by postwar optimism and Cold War anxiety, did not go uncontested. Seeds of resistance may be found in reactions to its public manifestations. In a 1953 review of Malraux's Museum without Walls, for example, Francis Henry Taylor, director of the Met, rejected the author's argument as a misguided form of escapism born of war-inspired fatalism about the human condition: “[Malraux] finds mankind wanting and seeks refuge from the tragic inadequacy of our society in the artifacts which man has left behind him.” “Maybe we can find comfort in the contemplation of a work of art but not necessarily a solution,” Taylor continued, “for the emptiness is of our own creation and cannot be filled with fragments of stone and canvas from exotic lands.”109 Tired and evidently disillusioned by the rhetoric of “gazing museums,” Taylor resigned from the Met soon after writing his review. No less wary of art's beguiling potential, Roland Barthes attacked the Family of Man exhibit when it came to Paris in the mid-1950s for its sentimental portrayal of a generalized humanity shorn of diversity. For Barthes, a superficial assurance that we are at bottom all the same obscured recognition of real differences that stood in the way of true understanding and justice: “Everything here, the content and appeal of the pictures, the discourse which justifies them, aims to suppress the determining weight of History: we are held back at the surface of an identity, prevented precisely by sentimentality from penetrating into this ulterior zone of human behavior where historical alienation introduces some ‘differences’ which we shall here quite simply call ‘injustices.’”110 The Family of Man relied on, and bolstered, a “myth of the human ‘condition,’” a myth dangerous in its failure to reveal the impact of what Barthes meant by History—the realities of race, politics, gender, creed, and class—on people's lives:

Any classic humanism postulates that in scratching the history of men a little, the relativity of their institutions or the superficial diversity of their skins (but why not ask the parents of Emmet Till, the young Negro assassinated by the Whites [lynched in Mississippi in 1955 for whistling at a white woman] what they think of The Great Family of Man?), one very quickly reaches the solid rock of a universal human nature. Progressive humanism, on the contrary, must always remember to reverse the terms of this very old imposture, constantly to scour nature, its “laws” and its “limits” in order to discover History there, and at last to establish Nature itself as historical.111

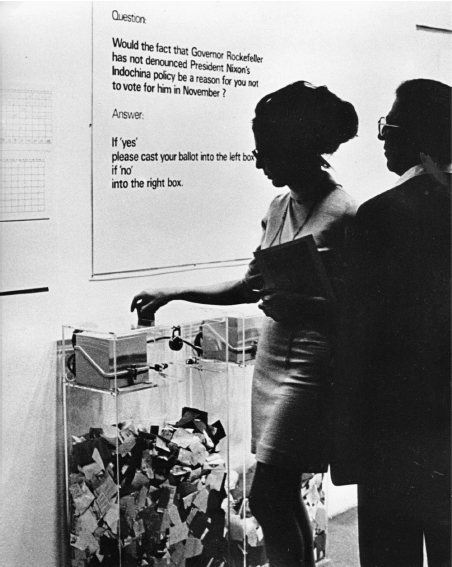

In the 1960s exposing the “imposture” of humanism and redressing the injustices of “History” became in effect the motivating purpose of social activism and critique, which included the civil rights and feminist movements, student protests on both sides of the Atlantic, and development of critical theory in academe. In that politically charged environment, the proclaimed autonomy of art and disengaged stance of art museums struck social activists and avant-garde artists as unacceptable establishment complacency and elitism. All of a sudden the postwar tranquillity of art museums was rudely disturbed by new calls for social relevance, community outreach, and heightened self-awareness. Bourgeois assumptions about public access to high culture were exploded by the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, whose important book The Love of Art (1966) demonstrated that aesthetic taste and judgment were the product of class and education (see chapter 4).112 Backed by Bourdieu's empirical research, activists behind the Paris riots of 1968 called for a greater democratization of culture. A year later, President Pompidou announced plans for the creation of a new multipurpose cultural institution at the heart of Paris, realized as the Pompidou Center in 1977 (see chapter 2). Also motivated by the radicalized political environment, revisionist art history began to challenge the depoliticized, formalist orthodoxy of Barr, Clement Greenberg, and their followers. Art entered a “postmodern” phase by renouncing formal purity, engaging with politics and mass culture, and “erupting” with language to make its politics perfectly clear.113 In the late 1960s art museums became the target of activist artists who used the visual arts as a vital medium of popular and political communication. In 1969 various radical groups—the Art Workers' Coalition (AWC), Women Artists in Revolution (WAR), and the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition (BECC)—led protests in front of New York museums against the Vietnam War and the underrepresentation of minority artists.114 Visitors to MoMA's Information show the following year were greeted by Hans Haacke's MoMA-Poll (fig. 18), which linked the museum and its administration, through trustee Nelson Rockefeller, to President Nixon's controversial policy in Indochina. Rockefeller, a four-term Republican governor of New York, was running for reelection that year. The poll asked: “Would the fact that Governor Rockefeller has not denounced President's Nixon's Indochina policy be a reason for you not to vote for him in November?”115 Hilton Kramer, chief spokesman for the cultural right, singled out Haacke's work as a sign of the dangerous and lamentable “politicization of art.”116

18. Hans Haacke, MoMA-Poll, 1970. © 2006 ARS, New York/ VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

In New York calls for action and “relevance” found a powerful voice within the museum world in Thomas Hoving, the maverick young director of the Met. In an address to the American Association of Museums in 1968, Hoving called on his colleagues to “get involved and become far more relevant,” to “re-examine what we are, continually ask ourselves how we can make ourselves indispensable and relevant.”117 Hoving then set an example of social relevance by staging the provocative exhibition Harlem on My Mind: Cultural Capital of Black America, 1900–1968. Hoving prepared the museum faithful for what was to come through the pages of the Met's monthly bulletin: “On the eighteenth of this month [January 1969] The Metropolitan Museum of Art will open an exhibition that has nothing to do with art in the narrow sense—but everything to do with this Museum, its evolving role and purpose, what we hope is its emerging position as a positive, relevant, and regenerative force in modern society.”118 Justifying the exhibition in advance, he resurrected the commitment to “practical life” advocated earlier by Dana and Henry Cole, only now practicality was concerned, not with industry or commerce, but with politics and activism. “'Practical life' in this day,” he wrote, “can mean nothing less than involvement, an active and thoughtful participation in the events of our time.”119 Though Harlem on My Mind borrowed Steichen's familiar mass media format and though the show was dedicated to buttressing, in Hoving's words, “the deep and abiding importance of humanism,”120 it made the mistake of coming down from an abstract plane of global humanity to the racially tense streets of New York City in the late 1960s. Some critics complained about the presence of photography in a high art museum, but what most disturbed the museum's loyal constituents, surely, was the introduction of race and social issues where they didn't belong. Instead of respite, Hoving offered a dose of social reality; in place of outright hope and celebration, he prompted reflection on social inequity, black-white relations, and an uncertain future.

For the majority of Hoving's professional peers, not to mention local critics and museum-goers, what Barthes meant by History was unwelcome in an art museum. In an essay prompted by the exhibition, entitled “What's an Art Museum For?” Katharine Kuh answered her own question by rejecting Hoving's social justification and suggesting instead that museums “offer us islands of relief where we can study, enjoy, contemplate, and experience emotional rapport with man's finest man-made products.” As for the Harlem show, she concluded: “The exhibition shows us the pain, but where are the fantasies?”121 A survey commissioned by ICOM in the same year as Harlem on My Mind revealed a museum-going public hostile to an overlap of art and “everyday” issues. By a clear margin, “images overtly or otherwise suggestive of catastrophe, human or social decay or other negative aspects of life” were held to be “offensive” and “out of place” in art and museums.122 There was plenty to celebrate in Harlem's history but also plenty to generate feelings of anxiety and guilt in a predominantly white, middle-class audience.

Hoving knew Harlem on My Mind would be controversial—indeed, he wanted it to be “an unusual event,” “a confrontation” that would change the “lives and minds” of its viewers “for the better.”123 According to the show's organizer, Allon Schoener, he and Hoving “saw the exhibition as an opportunity to change museums,”124 “the first step toward rethinking and expanding our concepts of what exhibitions should do.”125 Even the Bulletin announcing the show broke with precedent by featuring on its cover not a precious new acquisition but a young African American boy face turned upward (fig. 19), as if looking forward to a better tomorrow. Intoxicated by the radical air of the late 1960s, Hoving had a vision of museums on the move: “An art museum today can neither afford to be, nor will it be, tolerated as silent repository of great treasures…. We are deeply committed by conscience to getting involved…in the ferment of the times…. We intend to shake off the passivity that renders too many museums unresponsive and by default almost irresponsible.”126

With his “modishly-longer hair”127 and knowing references to “happenings,” zonked-out hippies, and SDS (Students for a Democratic Society), Hoving might have been in touch with the latest on the streets of New York, but he was out of step with the conservatism of his fellow museum directors elsewhere in the country. The Harlem exhibition sparked a swift and decisive backlash in the form of a redoubled affirmation of the value of the art museum as a haven of nonpolitical aesthetic contemplation. In the view of Hoving's antagonists (there were few supporters among his peers, it would seem), recent social turmoil, political instability, and war had made the art museum's function as respite from the world more relevant than ever. The chief spokesman for the disengaged museum was Sherman Lee, director of the Cleveland Museum of Art. In a speech delivered while the Harlem exhibition was still open, Lee insisted that “[t]he art museum is not fundamentally concerned with therapy, illustrating history, social action, entertainment or scientific research…. The museum is…a primary source of wonder and delight for mind and heart.”128 From the marble halls of Washington's National Gallery, John Walker concurred: “I am indifferent to [the art museum's] function in community relations, in solving racial problems, in propaganda for any cause.”129 In 1971 the Guggenheim Museum canceled an exhibition by Hans Haacke (including a piece attacking a New York “slumlord”) because of policies that “exclude active engagement toward social and political ends.”130 Leaders of the art world convened a few years later—with Lee but without Hoving—for a summit on the future of the museum and concluded: “Art museums should not become political or social advocates except on matters directly affecting the interests of the arts.”131 As the dust from the Harlem controversy settled, museum directors rallied around the position concisely put by George Heard Hamilton, director of the Clark Art Institute, that art museums were “most psychologically useful” to society by being irrelevant to the world outside; it was precisely in art's removal from daily life and the “effacement” of its social meanings that its “life-enhancing difference” could be felt.132 Once it was clear that art museums were not about to follow Hoving's lead, the soothing “irrelevance” of timeless art reasserted itself in museum discourse. Witness a talk given in 1974 by Otto Wittmann, director of the Toledo Art Museum, entitled “Art Values in a Changing Society”:

19. Cover of the Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin announcing the show Harlem on My Mind (January 1969).

In these precarious and unsettled times in which we all live, there is a great hunger for a sense of lasting significance…. The very nature of art and of the museums which preserve and present works of art reassures people of the continuity of human vision and thought and of the importance of their place in the vast stream of significant developments over centuries of time. A Mayan figure in Manhattan, a T'ang figure in Toledo[,] even though seemingly irrelevant to our culture today, can tell us much about humanity and human relationships…. These silent witnesses of the past can bridge the gap of time and place if we will let them…. The universal truths of all art should be shared.133

Activism of the 1960s produced the multiculturalism and outreach initiatives that have become the norm in museums in the decades since, and in terms of programming and audience museums are now more broadly representative than they were in 1970, but a reluctance to engage in potentially polemical political discourse remains in place. A number of prominent exhibitions in recent decades illustrate the broad turn in museum policy toward what can be called a depoliticized global humanism. A notable example was Jean-Hubert Martin's Magiciens de la Terre (Magicians of the Earth), held at the Pompidou Center in 1989. In that sprawling global survey, works by hundreds of contemporary artists from around the world, floating free of their original contexts and significations and endowed alike with what Martin called an “aura” and “magic” that set true art apart, were brought together on equal terms to further “a culture of dialogue.”134 Building on Malraux, Martin designed the exhibition to substantiate the maxim that the “multiplication of images around the world is one of the symptoms of the tightening of communication and connections…among the people of the planet.” Martin had also read his Barthes and was aware of the postcolonial politics of difference, so he understood that his selection and display of objects necessarily reflected his own European perspective and obscured “the complexity of certain local situations.” His intention was not to speak for other cultures, for he realized no one could do that; rather, it was to celebrate “the diversity of creation and its multiple directions.” Inevitably Magicians of the Earth revealed a problematic tension at the heart of much postmodern museology: although, as Martin confessed, it is “difficult, if not impossible to understand the cultural reality of…other cultures,” it is asserted that exposure to what we can never fully understand will nevertheless foster appreciation, respect, and eventually dialogue. The tentative solution offered to this dilemma of otherness is the possibility—the hope—that the strange may be made familiar through contact mediated by the museum.