4 THE PUBLIC

The transition from princely collection to public museum at the turn of the nineteenth century raised the question of who constituted the new museum public and how it should be served. The shift from private to public was gradual and uneven, occurring more rapidly and completely in some countries and at some institutions than at others, and nowhere did it occur without friction. Experts worried about the overexposure of delicate masterpieces to the gawking masses; bourgeois visitors complained about having to share a once-privileged space with their social inferiors and bemoaned new arrangements and precautionary measures aimed at the general public; guards monitored visitor behavior and attire, but little was done to instruct the novice. Throughout the nineteenth century, cartoonists made fun of the ignorant, reminding the uninitiated that they didn't quite belong.

The history of the art museum can be written as a history of efforts to reconcile the different needs and expectations of the museum-going public. The relationship between the museum and its publics has always been a live issue, but in recent decades it has become arguably the issue as external pressures have compelled museums to make public access and outreach an equal (and in some cases a greater) priority than the collecting and preservation of objects. The forces behind the transformation “from being about something to being for somebody,” as Stephen Weil put it, are ideological and financial.1

The “democratization of museums” has long been an ideal, but it has not always been a common cause among museum men, as the two epigraphs make clear. Tensions between the museum's goals to collect and preserve and to educate are built into the structure and staffing of museums. Some objects are deemed too delicate to be lent to exhibitions or displayed at all, limiting public access. Etymologically, the word curator comes from the Latin curare, to care, and to the extent that curators are trained and hired to care for their collections, they are drawn away from the visiting public. Care for the public is left largely to educators and volunteers, who, since their first appearance a century ago, have occupied a lower rung in the museum hierarchy. The exceptional rarity and value of art objects tend to make tensions between curators and educators especially prevalent in art museums. That the hierarchy is still alive and well is revealed by Philippe de Montebello's blunt admission: “To me, audiences are second…. Our primary responsibility is to works of art.”2 A further obstacle to democratization stems from the origins of our public museums in private collections. Alongside declarations of public service, art museums honor an aristocratic pedigree by occupying princely palaces (or purpose-built imitations of them) and cultivating ties to wealthy donors. While they invite the public to partake of their treasures, they also court collectors and patrons with a deference fit for a Renaissance prince. For some, the lingering aura of privilege is intimidating, but for just as many it is part of the allure. Like it or not, there would be no public art museums without the support of private benefactors.

What has tipped the balance toward audiences in recent decades has been the rise of social activism—political demands for museums to be more inclusive—and the need to meet escalating operating costs through higher attendance. Economic survival and the fear of being labeled elitist have combined to cast a negative light on Montebello's stated priorities. Curatorial attitudes notwithstanding, most museums can no longer afford to blithely concentrate on their collections at the expense of their visitors. At many museums, a shifting emphasis is reflected in diverse education and outreach initiatives, blockbuster exhibitions, and expanded recreational opportunities. A newspaper ad campaign for the Boston MFA from 1993 is representative of broader efforts at art museums to become all things to all people. Even the “top-ten” format of the ad borrows from a signature feature of a popular late-night television program (David Letterman):

| Top 10 Reasons to Visit the MFA This Fall | |

| 10. | Elvis was spotted wearing a security guard's uniform. |

| 9. | Chocolate Mousse Cake in Galleria Café. |

| 8. | The Museum Shop won Boston Magazine's “Best Shopping” Award. |

| 7. | “Robert Cumming: Cone of Vision”—his work can change the way you view the world. |

| 6. | It's changed a lot since you were in sixth grade. |

| 5. | Peter Tosh's “Red X” tapes on film through September 19. |

| 4. | Best people-watching off Newbury Street. |

| 3. | African sculpture—explore its secrets with a Nigerian art historian—September 29. |

| 2. | Nancy Armstrong and Robert Honeysucker sing Gershwin songs on September 26. |

| 1. | Escape to The Garden of Love in “The Age of Rubens,” beginning September 22. |

Art museum audiences have certainly grown since 1993, but it is less clear that higher numbers mean broader demographic diversity. At the same time, the turn to populism has frustrated seasoned art lovers who fear the loss of the museum they once knew. Recent programming trends have put pressure on traditional museological functions—scholarship, collecting, and conservation—not to mention works of art themselves, the most celebrated of which are frequently on loan to traveling exhibitions. Curators are now expected to be showmen as much as scholars and have drifted apart from their colleagues in academe, whose specialized knowledge is in turn increasingly marginal to the number-driven metrics of the successful museum. Shifting priorities are also changing the profile of museum directors and the composition of museum boards. In this time of contested ideals, growing popularity, and financial uncertainty, satisfying the museum's multiple constituencies constitutes one of the museum's greatest ongoing challenges.

The Age of Enlightenment

Collecting and enjoying art has long been an elite pastime. The emergence of art as an elite commodity coincided with the great age of Renaissance patronage and the creation of an aesthetic discourse that distanced art from social utility and privileged considerations of form, pictorial conceit, and authorship over function.3 As princes and kings turned to collecting art to affirm wealth and power, artists saw their own status rise and moved to define their craft as a liberal art worthy of comparison to poetry and philosophy. From newly created art academies a theory and history of art developed that articulated criteria for the proper evaluation of painting and sculpture. Emulation of princely example caused art collecting and appreciation to spread into polite society and become the mark of the gentleman. While not all aristocrats and wealthy bourgeois actively collected art, familiarity with classical antiquity and the fine arts conferred social distinction and indicated fitness to rule.4 By the eighteenth century an international network of critics and dealers, artists and collectors formed the infrastructure of an elite art world bound together by social contacts and shared discourse. Admission to the art world required appropriate social standing but also a mastery of critical terms and history. As mentioned in chapter 3, popular theorists such as André Félibien and Roger de Piles wrote books modeling connoisseurial dialogue for would-be art lovers, who in turn brought those texts to life in private collections across Europe. Though access to those collections was limited to recognized amateurs, much art could still be seen in churches and public spaces, but no matter where the art was displayed, the “public for art” effectively included only those who were capable of critically informed, aesthetically disinterested judgment. Conversely, those who responded to works of art with inappropriate emotion, or who attended to the content of a painting more than the way it was painted (the signified more than the signifier), revealed themselves as ignorant. These tendencies were eventually codified in the Enlightenment aesthetics of Kant and others, who defined legitimate aesthetic response as the prerogative of elevated beholders who were “freed from subjectivity and its impure desires.”5

Increases in wealth and education in the eighteenth century produced a concomitant expansion of the public for art, as reflected in the growth of the art market and the advent of public exhibitions and museums. Public sales and auctions became an early venue for an art-hungry public, and dealers used new marketing strategies—shop windows, newspaper ads, sales catalogs—to seduce the moneyed classes into the pleasures and social advantages of collecting.6 Engraving greatly extended the reach of high art, and the collecting of drawings became fashionable, but ownership of painting and sculpture required deep pockets. Critics demanded greater access to art on behalf of an expanding bourgeoisie without collections of their own, and from midcentury their calls were answered. Academies began to sponsor exhibitions of their members' work, the best known being the so-called Salon in Paris (from 1737) and the Royal Academy exhibitions in London (1768). Temporary exhibitions promoted artists' careers by introducing their work to potential patrons, but they also proved enormously popular with the public at large, consistently attracting large and diverse crowds. Overnight the public for art expanded beyond established amateurs and the cozy confines of collector's cabinets, and in the process became fragmented and difficult to define. As early as 1750 the painter Charles-Antoine Coypel remarked that the Salon attracted “twenty publics of different tone and character in the course of single day: a simple public at certain times, a prejudiced public, a flighty public, an envious public, a public slavish to fashion…. A final accounting of these publics would lead to infinity.”7 Self-styled critics stepped forward to guide this new and amorphous public. Private entrepreneurs seized on the public's enthusiasm and created commercial venues, such as Sir Ashton Lever's Museum in London (1773) and the Colisée in Paris (1776), offering potent mixtures of art, curiosities, and popular entertainment.8 The blurring of boundaries between high and low culture jeopardized the integrity of the fine arts and provoked disdain from the establishment, though the general public evidently paid little attention to such distinctions.

For our purposes the most significant innovation in eighteenth-century Europe was the gradual opening of royal and princely galleries to an increasingly broad cross section of the public. In the middle decades of the century, private and princely collections in Paris, Rome, Berlin, London, St. Petersburg, Florence, Stockholm, Vienna, Dresden, Düsseldorf, Kassel, and elsewhere opened to the public with varying degrees of liberality.9 In Paris and Kassel, museums were open to all (though it is not clear who actually came), while in Berlin and London visitors needed to apply in advance, and in Vienna entry was barred to those without clean shoes. International travelers on the Grand Tour tended to be welcome everywhere. As the Age of Absolutism gave way to the Age of Enlightenment, patronage of museums and related institutions became the mark of enlightened rule and superseded ceremonial pomp and grandiose monuments as a form of princely patronage. In Paris Louis XVI (1754–93) chose not to erect a public statue of himself in emulation of his Bourbon ancestors and instead invested in the Louvre museum as his monument to posterity. Many collections were relocated or reinstalled according to scholarly standards by newly hired curators. Those curators published catalogs (e.g., figs. 67–70) making the collection accessible to educated readers. Once opened to the public, princely collections came to be seen as the national patrimony, stewardship of which became a measure of good government. These fundamental transitions, part and parcel of the transition toward modern nationalism, occurred at different rates in different countries, but the signal moment in the evolution of the public art museum was undoubtedly the creation of the Louvre during the French Revolution.

As we have seen in chapter 1, the Louvre, founded in 1793 at the height of the Revolution, was “public” and “national” like no museum before it. Full of the confiscated and nationalized property of church and crown and housed in a royal palace turned palace of the people, the Louvre museum embodied and made tangible the principles of liberty, equality, and fraternity for which the Revolution stood. Admission was free to all, and shared enjoyment of the republic's patrimony aimed to cement the bonds of citizenship and foster devotion to the nation. Foreigners were surprised to be admitted without an introduction or a fee, and once inside they were equally surprised to find themselves rubbing shoulders with “the lowest classes of the community.”10 That the latter stood out so conspicuously revealed, however, that the stratified publics of the ancien régime could not so easily be made one. Even republican journals satirized the uninitiated, revealing the bourgeois underpinnings of the museum (and the Revolution itself).11 The mingling of classes and social types at the museum (and adjoining Salon) made the Louvre a microcosm of the modern social order and the setting for some of Honoré Daumier's most enduring caricatures. In one, “The Egyptians weren't good-looking!” (fig. 88), a humble family commits a faux pas no bourgeois would want to make in misconstruing the hieroglyphic conventions of the ancient Egyptians. Nothing was done to help the uneducated understand what they saw. There were no education programs or text panels in the gallery, and the printed catalogs sold at the door were beyond the means of the poor, assuming they could read. Absent prior knowledge or active gallery instruction, the methodical arrangement of the paintings, so instructive to the amateur, meant little to the man in the street.12

88. Honoré Daumier, “The Egyptians weren't good-looking!” 1867. Wood engraving.

At odds with the symbolic role of the Louvre as embodiment of a regenerated, egalitarian society was its propaganda value as a showcase of republican culture. To counter the impression of an anarchic society governed by mob rule, summary justice, and contempt for tradition, the Louvre offered itself as the supreme manifestation of aesthetic ideals shared by all civilized Europeans. At least as important as the local public, therefore, were international travelers who would take home with them a lasting image of canonical masterpieces preserved and displayed according the highest standards. To ensure that they did, a number of days each week were set aside for their exclusive enjoyment. Some foreign visitors were also interested in the spectacle of the mass public and came back during general open hours. Though the public days “were not suited to study or careful examination and reflection,” noted Carl Christian Berkheim from Germany, “on the other hand, it is interesting to hear the often bizarre observations that are made and to observe the hordes of people drawn from all classes and walks of life as they traverse the gallery.”13

Tourists flocked to the Louvre, as they have done ever since (today more than half of the Louvre's six million visitors are foreigners). At the height of his power, Napoleon remarked, “[I]t would please me to see Paris become the rendezvous of all Europe,” and thanks to the Louvre it largely did.14 As the city's chief cultural attraction, the museum figured prominently in every guidebook and itinerary. For many it was the first port of call, and repeat visits were customary. The fall of Napoleon and the prospect of the Louvre's dispersal prompted one Henry Milton to confess, as he crossed the English Channel for the first time: “I much doubt whether I should have taken the trouble to visit France had it not been for this collection.”15 John Scott, in his Visit to Paris in 1814, tells of a shopkeeper who made the journey with him with the express purpose of seeing “for himself what was fine in the Louvre.”16 In the stories of these early visitors to the Louvre we see the fault lines that divided, and still divide, the art museum public. Experienced travelers like John Scott recognized with regret that the Louvre would fundamentally change the way people engaged with works of art: the days of the Grand Tour and pleasures of private viewing were coming to a close, replaced by something new and public. Scott remarked that the combined glories of the new museum shone “with a lustre that obscures every thing but itself. In it are amassed the choicest treasures of art, that have been taken from their native and natural seats, to excite the wonder of the crowds instead of the sensibility of the few.”17 Alongside Scott there were fellow aristocrats, like the party of Sir John Dean Paul, banker, baronet, and author of The ABC of Fox Hunting, who evidently cared little for art but were drawn to the Louvre as a novel spectacle and rendezvous for the exchange of society gossip.18 There were also earnest bourgeois, like Scott's shopkeeper, or Henry Milton, who valued the convenience of a centralized museum and viewed those who failed to appreciate its wonders with contempt. “It is laughable,” Milton remarked, “to observe how very few are really attentive to the treasures which surround them.”19 Milton perhaps had more sympathy for the illiterate Parisian than he did for the likes of John Dean Paul. In any event, early testimonials suggest that public museums have always been a space of social encounter in which the needs of the uneducated and the elite, the art lover and the shallow tourist, democracy and diplomacy, are in play and potential conflict.

One further constituency served by the revolutionary Louvre was practicing artists, who, together with tourists, were given privileged access to the museum for the purpose of copying the Old Masters. The study and selective imitation of past art had been a cornerstone of artistic theory and training for two hundred years, and this practice was institutionalized at the Louvre and other museums. Art schools were often associated with and built near art museums well into the twentieth century. But over the past century the decline of copying, the accelerated pace of avant-garde movements, and the ambivalent place of contemporary art in many mainstream museums have together reduced the standing of living artists among the museum's publics.20

Victorian Ideals

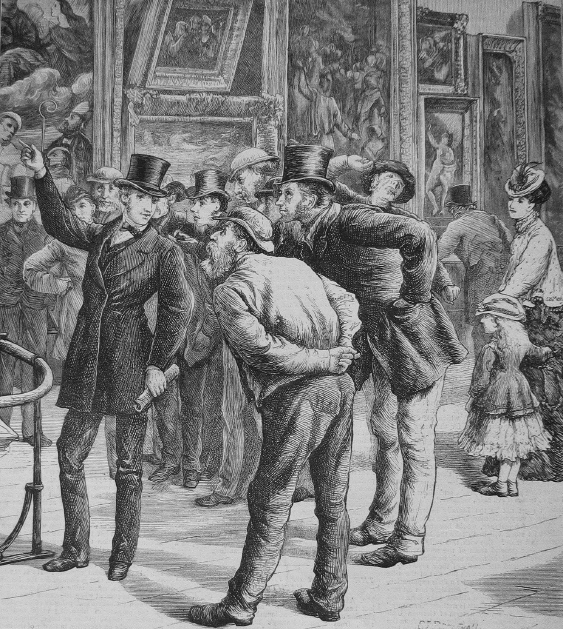

With the spread of museums and their integration into the cultural apparatus of the modern state after 1815, the question of the public became not so much who was granted admission, for in time virtually all were welcome, but how museums could be called upon to shape the public in keeping with perceived political and social needs. In what ways could museum-going benefit the public, and thus the nation as a whole? During the Victorian era and beyond, the museum public was commonly represented as an idealized projection of what patrician politicians and social critics hoped it would become (fig. 89). The rhetoric of aspiration informed official discourse and mission statements and tells us more about what a museum aimed to do for its visitors than what it actually did. Throughout the nineteenth century, utility and progress, instruction and innocent recreation, were the watchwords for all public institutions, including art museums. A “gallery…erected at the Nation's expense…must of course be rendered as generally useful as possible, every one being admitted capable of deriving from it enjoyment or instruction,” according to Gustav Waagen, director of the Berlin Museum.21

During the Victorian era, in the context of unprecedented challenges arising from the Industrial Revolution, utility was measured primarily in socioeconomic terms. In Britain especially, owing to its vanguard position in the industrial movement, an explosion of urban populations teetering on the edge of poverty, immorality, and anarchy prompted the need for new social controls, systematic education, and healthy recreation. The desire to control and civilize the masses was all the more pressing as successive political reforms gave voting rights to larger segments of society. Politicians supported the diffusion of museums in the belief that they would contribute to the moral and intellectual refinement of “all classes of the community” and the formation of “common principles of taste,” to quote from a parliamentary report of 1853.22 For Matthew Arnold, writing in 1869, a common culture disseminated through educational institutions should take the place of organized religion as the necessary adhesive for the new society in the making.23 Arnold believed in the top-down imposition of what we would today call canonical values as the means of elevating the populace to a more enlightened level of existence. The hero of Walter Besant's novel All Sorts and Conditions of Men (1883) took the belief in the softening effect of culture to the point of caricature when he insisted that the arts could tame “the reddest of red hot heads”: “He shall learn to waltz…This will convert him from a fierce Republican to a merely enthusiastic Radical. Then he shall learn to sing in part: this will drop him down into advanced liberalism. And if you can persuade him to…engage in some Art, say painting, he will become, quite naturally, a mere conservative.”24

89. “A Party of Working Men at the National Gallery,” The Graphic, August 6, 1870.

London's National Gallery went beyond the museums of Paris and Berlin by actively encouraging visits by the laboring classes. Despite concerns that the smoky chimneys and noxious breath of the poor threatened the nation's pictures, the gallery remained in Trafalgar Square within reach of the “grim city-world of stone and iron, smoky chimneys, and roaring wheels.”25 A survey of area businesses in 1857 revealed that the gallery was indeed popular with local tradesmen and workers. During the previous year, among various firms surveyed, 338 men from Jackson the Builders went to see the pictures 583 times; 46 employees of Hooper the Coach Makers made 66 visits; and Cloughs the Printers reported 117 workers visiting the gallery 220 times.26 The Working Men's Club and Institute organized tours, and the Pall Mall Gazette published a guide aimed at laborers that went through many editions from the 1880s.27

For those with firsthand experience of conditions in London's East End, however, Trafalgar Square was too remote to make a difference, and rather than oblige workers to travel to the West End, the founders of the Whitechapel Gallery, the Reverend Samuel Barnett and his wife, Henrietta, brought high art to the poor. Starting in the early 1880s, the Barnetts organized an annual exhibition of paintings, borrowed from artists and collectors, intended to stimulate moral sentiments, patriotism, and a feeling for beauty among the residents of the East End slums and settlement houses. As the vicar of St. Jude's, Whitechapel, Barnett spoke with authority when he said: “[P]ictures in the present day take the place of [biblical] parables.”28 By his reckoning 95 percent of the local population did not attend church; organized religion had lost its moral force where it was most needed.29 Open every day, including Sundays, for two to three weeks around Easter, the exhibitions proved enormously successful. The first year's exhibition, in 1881, drew ten thousand visitors; a decade later attendance had risen to seventy-three thousand. In 1898, the temporary exhibitions became the basis of a permanent gallery (the present Whitechapel Gallery) erected alongside the public library. For her part, Henrietta Barnett was an important advocate of philanthropy and among the first to suggest that women had a special role to play in outreach efforts in museums and galleries. “Why should the poor spend their hardly earned pence in taking the journey to see treasures the beauty of which they do not half understand, having never been educated to see and appreciate them?” she asked. If women devoted themselves to bringing “beauty home to the lives of the poor,” through the loan of pictures or by taking “groups of her poor friends to see galleries or exhibitions,” “they would find a field of work but yet little trodden, a wealth of flower-rewards only waiting to be plucked.”30 Well-educated women would soon become the mainstay of education departments and volunteer programs in twentieth-century museums (fig. 90).

90. Apprentice Docents, Newark Museum, 1929–30 (from left to right: Freda House, University of Chicago; Lois Cole, Wheaton College; Helen Jenkins, Mount Holyoke College; Grace Jones, Wheaton; Rosaline Forman, Mount Holyoke; Harriet Seelye, Smith College; Emily Cooley, Wilson College; Caroline Green, Wheaton). Photo courtesy of the Newark Museum.

The South Kensington Museum also had populist goals, as discussed in chapter 1. Its founder, Henry Cole, hoped the museum would stimulate native design and industry while improving the taste of ordinary Britons and providing amusing diversion during hours of leisure. Given the enormous popular success of the Great Exhibition, staged nearby in Hyde Park, a permanent museum displaying household objects and decorative arts had a good chance of being “useful” on numerous levels. Promotion of everyday aesthetics and the conscious rejection of the art connoisseur's priorities contributed to making the South Kensington Museum the most popular museum in Britain. Annual attendance rose from 456,000 in 1857 to over a million in 1870. The combination of free admission, evening hours, and a popular holiday could boost single-day attendance above twenty thousand. Cole envisaged similar museums achieving like success across the land, bringing about a revolution of popular taste among “all classes of people.”31 Just as medieval England once “had its churches far and wide,” so modern Britain would have its engines of social reform in the form of museums.32

As we might expect, given the capitalist underpinnings and trickle-down aesthetics of the Victorian museum, the ideal public consisted of those most eager to help themselves. Virtually everyone who spoke on the subject agreed with Ruskin when he said that museums, while instructive for the multitude, must not be “encumbered by the idle, or disgraced by the disreputable.” He wrote to a correspondent in Leicester: “You must not make your Museum a refuge against the rain or ennui, nor let into perfectly well-furnished, and…palatial rooms, the utterly squalid and ill-bred portion of the people. There should indeed be refuges for the poor from rain and cold, and decent rooms accessible to indecent persons…but neither of these charities should be part of the function of a Civic Museum.”33 Similarly, Gustav Waagen was in favor of discouraging visits from those “whose dress is so dirty as to create a smell obnoxious to the other visitors” or babes in arms escorted by their wet nurses. In his opinion, both groups were too plentiful at London's National Gallery, obliging him “more than once…to leave the building.”34

Excluding the squalid and ill-bred suited the middle classes, but it also benefited the aspiring laborer, for, as Tony Bennett has argued, the Victorian museum was a “space of emulation” where watching others and being seen was as important as scrutinizing the art. To the extent that museums functioned as arenas “for the self-display of bourgeois-democratic” values, they had to offer an environment in which appropriate civil behavior was encouraged and its opposite forbidden.35 For Arnold, the purpose of culture was ultimately “to do away with classes; to make all live in an atmosphere of sweetness and light,” which in effect entailed the eventual “embourgeoisiement” of society.36 To achieve societal progress, “all our fellow-men, in the East End of London and elsewhere, we must take along with us in the progress towards perfection,”37 and this could best be achieved by helping those who most wanted to help themselves. “The best man is he who most tries to perfect himself, and the happiest man is he who most feels that he is perfecting himself,” said Arnold.38 As we have seen, for Arnold, the spread of culture would address not only the brute ignorance of working men and women but also the shallow materialism of the expanding middle classes. Material wealth was not an end in itself to be pursued for individual satisfaction but the means to lift all toward an “ideal of human perfection and happiness.”39 The beauty of philanthropy was, and remains, that it allowed those who supported museums to prove their own sophistication while discharging a civic duty by lifting the less fortunate around them upward toward the light.

The goal of museum advocates was to transform art from, as Arnold put it, “an engine of social and class distinction, separating its holder, like a badge or title, from other people who have not got it,”40 into a source of common inspiration, and to make museum visits a form of recreation for all classes. Henry Cole envisaged evening hours at South Kensington as a great boon to working-class families: “The working man comes to this Museum from his one or two dimly lighted cheerless rooms, in his fustian jacket, with his shirt collars a little trimmed up, accompanied by his threes, and fours, and fives of little fustian jackets, a wife, in her best bonnet, and a baby, of course, under her shawl. The looks of surprise and pleasure of the whole party when they first observe the brilliant lighting inside the Museum show what a new, acceptable, and wholesome excitement this evening entertainment affords to all of them.”41

Evidence and common sense suggest, however, that the barriers of class were not so easily overcome, that the hard-won politesse of the bourgeoisie was not graciously forsaken in the interests of class harmony. The space of emulation could also be a space of contempt, condescension, and disappointment. Henrietta Barnett, eavesdropping at the Whitechapel in the hope of gleaning evidence of some good rubbing off on her East End flock, tired of people wondering how much the pictures were worth and at times overheard the voice of daily struggle: “Lesbia, by Mr. J. Bertrand, explained as ‘A Roman Girl musing over the loss of her pet bird,’ was commented on by, ‘Sorrow for her bird, is it? I was thinking it was drink that was in her’—a grim indication of the opinion of the working classes of their ‘betters’; though another remark on the same picture, ‘Well, I hope she will never have a worse trouble,’ showed a kindlier spirit and perhaps a sadder experience.”42 Following a visit to the same gallery in 1903, Jack London concluded that the poor “will have so much more to forget than if they had never known or yearned.”43 One thinks of Henry Cole's family returning to their “dimly lighted cheerless rooms” after seeing the beautiful things at South Kensington.

In a society dominated by class, in which art and cultural knowledge continued to circulate as elite commodities and museums depended on the rich for support, it was at best highly idealistic to expect art to cease to function as a badge of privilege. Moreover, the bourgeois ideal of elevated aesthetic contemplation, manifested in Hazlitt's account of the Angerstein collection from chapter 1 (“We are transported to another sphere…we breathe the empyrean air”), became difficult to achieve when the Angerstein pictures went to Trafalgar Square and the presence of laborers and wet nurses polluted the air with noxious fumes. On those days popular with the broad public, the likes of Hazlitt and Gustav Waagen were inclined to stay at home. For utilitarian reformers like Greenwood, “art should not be approached as something unusual…for the aristocratic few, and not for the many,”44 but for the amateur it was precisely what made art unusual, rarefied, and difficult to grasp that mattered.

The Progressive Era: Museums for a New Century

What could public museums do to demystify art and bridge the gap between the informed and the ignorant? The need to overcome barriers to broad participation in museum culture led to two major innovations: first, the systematic rearrangement of collections in the interest of visitor comfort and comprehension, discussed in chapter 3; and, second, the development of museum-based education programs. By the late nineteenth century, the growing clutter of the Victorian museum had come to be seen as an impediment to popular instruction. Swelling collections and increased attendance raised visitor fatigue and diminished the visibility of the most important objects on display. William Stanley Jevons, a staunch supporter of public libraries, had his doubts about the utility of museums because of the failure to make them comprehensible and appealing to the broad public. In particular he lamented the lack of attention paid to presentation and the visitor's physical comfort. At South Kensington, for example, “The general mental state produced by such vast displays is one of perplexity and vagueness, together with some impression of sore feet and aching heads.”45 Jevons led a growing chorus of voices recommending simpler displays, clearer organization, and public education. Recognizing different publics with different needs, Jevons and others called for a distinction to be made between public galleries featuring highlights for general consumption and research collections containing everything else for the use of students and scholars. A Professor Herdman of Liverpool went so far to say: “It should always be remembered that public museums are intended for the use and instruction of the general public…and not the scientific man or the student.”46 Not only should the public's attention be focused on masterpieces, but the underlying system of classification should also be made visible. For Greenwood, “[T]he usefulness of a museum does not depend entirely so much on the number or intrinsic value of its treasures as upon proper arrangement, classification, and naming of the various specimens in so clear a way that the uninitiated may grasp quickly the purpose and meaning of each particular specimen.”47

German museum men reached the same conclusions during the reform movement of the 1880s and 1890s sponsored by Kaiser Friedrich III.48 Wilhelm von Bode, Alfred Lichtwark, Karl Osthaus, and others helped to redefine the modern museum around notions of simplified displays and public pedagogy. Lichtwark, director of the Hamburg Kunsthalle, was especially active on the latter front, advancing his museum's role as an “institution…actively engaged in the artistic education of our community” through programs for children and adults alike.49 New German thinking about education and museum management and design formed an important resource for museum pioneers in the United States in the decades on either side of 1900, and nowhere more so than in the planning of Boston's new Museum of Fine Arts, opened in 1909.

As we have seen, the shift from the old to the new museum entailed abandoning a utilitarian purpose and collection in favor of high art and aesthetics. It also ushered in a new commitment to public education. “The problem of the present,” wrote Benjamin Gilman, the museum's longtime secretary, “is the democratization of museums: how they may help to give all men a share in the life of the imagination.”50 Gilman and his colleagues at the MFA undertook a number of influential initiatives intended to make the museum more effective as a tool of public education. As discussed in chapter 3, secondary objects were relegated to the study collection on the lower floor while the best art was presented to the general public on the main floor in simple, spacious, well-lit galleries, “to help the visitor to see and enjoy each object for its own full value.”51 Gilman's training in the nascent discipline of psychology made visitor response a priority and led to improvements in lighting and hanging, seating and signage, all aimed at reducing what he termed “museum fatigue.” Under Gilman's leadership a broad array of education programs came into being. Acknowledging that the ability to appreciate and understand art was “left aside in our educational system,” Gilman invented the idea of gallery “docents,” whose purpose was to provide “companionship in beholding,” or what today we would call art appreciation. The purpose was not to offer a watered-down art history but to call attention to the “vital elements in a work of art,…insuring that it is really perceived in detail, and taken in its entirety.”52 The docent program was a great success. In 1916, for example, some thirty trained docents served 4,300 visitors “of both sexes and all classes” without charge. In that same year the museum also welcomed 5,600 schoolchildren and their teachers, as well as a further 2,380 students who came on their own. Teacher training was offered, also free of charge, and museum staff visited every school in Boston and distributed some twenty-five thousand reproductions for classroom use. During the summer 6,800 underprivileged children were bused to the museum from settlement houses, and a further 850 children attended story hour on Saturday afternoons (repeated on Sundays for Jewish children).53 The effort to cultivate interest among the young was particularly forward looking and influential. “If the children of Boston can learn to enjoy works of art as children,” wrote the director, Arthur Fairbanks, “a more wide and real and intelligent enjoyment of art may be expected in another generation than exists today.”54 Sunday opening hours at Boston and other museums, though controversial at first for religious reasons, greatly expanded the public. “The Sunday visitors especially represent the American public at its best,” wrote Gilman. “All sorts and conditions of men contribute their quota to the well-behaved, interested, almost reverent throng.”55 In 1918 the MFA abolished admission fees (it had been free hitherto only on certain days) to encourage adult visitors, and attendance soon doubled. In 1924, Gilman's last year at the museum, attendance rose above four hundred thousand, and more than nine thousand people signed up for docent tours. To supplement guided tours, Gilman wrote a jargon-free handbook of the collection, copies of which were available for consultation in the galleries and for purchase at the front door. During the same years, a similarly impressive record of educational programming and docentry was achieved at the Metropolitan Museum in New York under Henry Watson Kent and at Newark under Dana.56

91. Instructor Ruth Krupp leading a class at the Toledo Museum of Art, 1936. Photo courtesy of the Toledo Museum of Art Archives.

Gilman and Kent's reforms in education and classification provided a blueprint for art museums from the 1920s; by the Second World War scarcely a museum could be found that had not culled its collections, adopted simplified display techniques, and embraced public participation as an ideal. In the United States, especially, education programs of the sort pioneered in Boston and New York became commonplace. In 1936, for example, the Toledo Art Museum in Ohio published a report that represents a high-water mark for prewar efforts to make a local art museum central to an urban community (fig. 91). The report opened with a straightforward statement of mission: “The Toledo Museum purpose is to lead people to like art, to apply its principles to their daily living, and to discriminate between good and bad pictures, sculpture and music. It aims primarily to help them to enjoy looking at art and listening to music, and teaches them how to go about it to receive their fullest reward.”57 Backing the rhetoric was an astonishing range of educational activities that reached all ages and walks of life. Beyond the usual “talks, tours, illustrated lectures, forums on current exhibitions and talks which relate art to the subject matter of the elementary and secondary schools,” the museum offered practical instruction in music and art for children and teens from the age of five (in art alone “students fill twenty-one classes of the Museum school each Saturday and delight in their thirty-eight weeks course in color, design, water color, drawing and modeling”); classes for women in clothing and home furnishing; classes for department store buyers, managers, and salespeople; classes for designers from local industries; general classes in color and design for dressmakers, florists, contractors, architects, and furniture dealers; evening music classes for adults; and frequently scheduled concerts and “educational movies.”

At the same time, however, the interwar years witnessed a sharp increase in the professionalization of museum staff, which had the effect of separating curatorial responsibilities for acquiring and arranging works of art from the work of public interpretation. While educators and docents worked with an expanding range of visitors, newly minted curators, trained at universities as art historians, turned inward on their collections. Though committed to a broadly democratic mission, museums in the United States were equally determined to catch up to their European counterparts in terms of their holdings, making it imperative that “the curatorial staffs…be recruited with…reference to scholarly competence and training,” in the words of Charles Rufus Morey, chairman of Princeton's art history department.58 Paul Sachs, whose Museum Course at Harvard trained many prominent curators and directors between the wars, argued vigorously that a museum's integrity depended on maintaining the highest scholarly standards. Taking a swipe at populist programming, he told the dignitaries assembled for the opening of MoMA in 1939:

Let us be ever watchful to resist pressure to vulgarize and cheapen our work through the mistaken idea that in such fashion a broad public may be reached effectively. In the end a lowering of standards must lead to mediocrity and indeed to the disintegration of the splendid ideals that have inspired you and the founders…. The Museum of Modern Art has a duty to the great public. But in serving an elite it will reach…the great general public by means of work done to meet the most exacting standards of an elite.59

Needless to say, meeting the “most exacting standards of the elite” inevitably meant that the narrow cut of collectors, scholars, critics, and fellow museum professionals, not the general public, constituted the curator's primary audience. “The museum of the future,” concluded Sachs, “should be a comprehensive and enduring community of scholars” pursuing the functions of “study, teaching and research.”60 Instead of museums reaching down to an uninformed public, Sachs implied that the public should rise up to the standards of those in the know. Dana, for one, had warned that curators, “once enamored of rarity,” were at apt to “become lost in their specialties and forget their museum…its purpose…[and] their public.”61 And according to Theodore Low, a pupil of Sachs who took an unusual turn (for a man) into museum education, that is precisely what happened. Writing in 1942, Low lamented the failure of American art museums to live up to the democratic promise of their founding charters and laid much of the blame on the seductive “charms of collecting and scholarship.”62 The mutual interest of benefactors and directors (drawn from the ranks of curators) in collection building on the European model had reduced education to a “moral quarantine” within the museum, “a necessary but isolated evil.”63 “As a result museum men have drifted further and further away from the public.”64 Twenty years later the situation had not changed, according to the director of Washington's Smithsonian, who noted that curators regarded “teaching and explanation” as a “descent from the sacred to the profane.”65

At the root of the problem, Low felt, was the narrow focus on connoisseurship in graduate art history programs, including Sachs's Museum Course, in which “the approach to the public” had been ignored in favor of “the training of connoisseurs for curatorial work.”66 No doubt because conventional doctoral programs, like Princeton's, viewed (and still view) vocational training with contempt, Sachs was careful to emphasize his unequivocal commitment to museum scholarship.67 It is telling that neither Gilman nor Dana figured prominently in the Museum Course bibliography despite their standing in the field. In 1945, Francis Henry Taylor, then director of the Met, echoed Low by arguing that Americans, “of all the peoples of history, have had a better, more natural, and less prejudiced opportunity to make the museum mean something to the general public,” yet had failed.

We have placed art…both literally and figuratively, on pedestals beyond the reach of the man in the street…. He may…visit the museum on occasion, but he certainly takes from it little or nothing of what it might potentially offer him. This is nobody's fault but our own. Instead of trying to interpret our collections, we have deliberately highhatted him and called it scholarship…. There must be less emphasis upon attribution to a given hand and greater emphasis upon what an individual work of art can mean in relation to the time and place of its creation…. There must also be a more generous attitude on the part of the scholar toward the public.68

What Taylor and Low were speaking to was the proper balance between the goals of collecting and interpretation, an equilibrium difficult to achieve owing to the imbalanced power structure within the museum: on one side curators and directors emulating a European model and academic standards, and on the other educators mindful of a broad public hungry for knowledge. Low meant it as a compliment when he said of Dana: “He was an American rather than a pseudo-European…and thought in broad terms of the American social scene.”69

92. Sixty-ninth Street Branch Museum, Philadelphia, 1931.

To be sure, the 1930s witnessed an extraordinary expansion of educational activity and outreach in U.S. museums, motivated in good part by social pressures arising from the Great Depression. Writing in 1932, Paul Rea, author of The Museum and the Community, an influential study sponsored by the Carnegie Corporation, argued that museums should offer more in the way of public service in exchange for the tax support they received. One man who took Rea's study to heart was Philip Youtz, who directed the short-lived, Carnegie-funded Sixty-ninth Street Branch of the Philadelphia Museum of Art (fig. 92), one of a number of branch museums created in the 1920s and 1930s in imitation of branch libraries (pioneered by Dana in his first career as a librarian) to spread art to the masses. Like Dana, Youtz believed that museums had much to learn from department stores and commercial venues in their effort to reach the community, and he located his branch museum in a storefront across the street from a supermarket and a five-and-dime. Objects displayed attractively in street-level windows lured passersby, and the museum remained open daily until 10:00 P.M. Whereas most museums arranged their collections “according to the tastes and interests of the staff and trustees” and the public encountered only the guards, at the Sixty-ninth Street museum the interests of “the public at large” were borne in mind and the staff “maintained intimate contact with the public it serves.” “It is high time that museums of all kinds became more definitely oriented toward the public,” Youtz declared. “The aloof policy inherited from old private collections must be abandoned and museums must accept the leadership in public education.”70 When he took over at the Brooklyn Museum in 1934, Youtz sought to infuse the stately Beaux Arts temple with the populism of a branch museum, stating at the outset, “[T]he public is the starting point, not the collections.”71 Following Rea, Youtz believed museums had an obligation to serve the public, especially in difficult times like the Depression. “The detachment and calm which is experienced by a visitor to a museum helps to maintain public morale in the face of severe social tension,” he wrote. “Museums offer a necessary and essential form of recreation to an over-burdened and distraught citizenry.”72

While branch museums were short-lived owing to a lack of consistent funding, mainstream art museums on both sides of the Atlantic explored ways of making their collections seem more relevant to their audiences. For a brief moment before the war, numerous Western museums experimented with programs that promoted cultural history in ways that seem surprising today. In his survey of educational trends, Theodore Low quoted prominent museum men such as Victor d'Amico, head of education at MoMA, who held that “art is an expression of a culture and society” and that “to isolate a work of art from its background and set it up alone in a glass case is to deprive it of the fullness which gives the work significance and beauty.”73 As early as 1930, Philip Youtz stated: “Art is meaningless without its social setting…. To try to study art apart from sociology, economics, social history, and anthropology, is as ridiculous as it would be to investigate coral without considering the life cycle of the zoophytes which produce it.”74 A few years later he described the tendency to segregate art from life as the gravest symptom of “museumitis,” a disease that could be cured only by “a new kind of art education that shall stress the vital social connection of art.” “Appreciation courses have failed,” he said, because they neglected “the rich fabric” of a culture and made an “idol” of art.75

Yet Youtz and Low, Taylor and d'Amico understood that their efforts to promote social art history ran counter to the rising tide of “aesthetic idolatry.” Everywhere one turned, Newark and Brooklyn aside, one found Gilman's “appreciative acquaintance” alive and well. Even museums commended by Low for their educational initiatives, such as the Toledo Museum, happily admitted that “their primary interest is in the development of public appreciation of art.”76 Under the leadership of Sachs's disciple Alfred Barr, MoMA established new curatorial standards with respect to the quality of acquisitions and shows, installations, and scholarship. Consistent with the clean, new, autonomous interiors of the museum, yet evidently at odds with the philosophy of his education staff, the exhibitions organized by Barr in the 1930s and the exemplary catalogs he wrote to accompany them were emphatically visual in nature; installation and text combined to encourage familiarity with the “formal” properties of modern art and the stylistic influences linking one artist and school to another. Barr tended to neglect the social import of avantgarde movements like the Bauhaus, Dada, and De Stijl. In the mid-1930s Meyer Schapiro criticized Barr for his neglect of the social and political contexts for modern art, but Barr was indifferent to such concerns, and his example proved enormously influential for later museums.77

On one important subject—the display of art—curators and educators could agree. The introduction of single-row hangs, controlled electric lighting, and the elimination of architectural distraction all favored the easy visual consumption of select masterpieces. Pioneering studies of visitor behavior conducted in the late 1920s and 1930s by the Yale psychologists Edward Robinson and Arthur Melton had demonstrated empirically that the dense arrangements prevalent in older museums increased fatigue and loss of attention (fig. 74). But in the process of streamlining gallery installations, interpretation in the form of gallery texts and docent tours came under review as a potential distraction in itself. As we have seen, the ethos of the modernist museum dictated that masterpieces speak for themselves, rendering suspect efforts to speak on their behalf. Even Benjamin Gilman was ambivalent about wall labels and guided tours. Gilman created his docent program because he understood that many people needed instruction to help them appreciate what they saw, yet he also worried that the “the use of galleries for vive voce instruction may become a disturbance of the public peace for him who would give ear to the silent voices therein.”78 Similarly, though he made heavy use of written gallery aids he looked forward to the day when they would no longer be necessary. Indeed, when the new Boston museum was under construction Gilman experimented with a mock-up gallery without labels: “The impression was that of ideal conditions, surely to be realized in the museum of the future.” Without labels the works of art “were able to create about themselves a little world of their own, most conducive to their understanding.”79 Gilman's successors shared his misgivings, much to the frustration of populist critics. In his 1935 study, Arthur Melton criticized the minimalist labeling practices of art museums for conflating “the typical visitor” with “those individuals who manage museums” and omitting “essential information which is assumed to be the knowledge of everyone.”80 The left-leaning museum critic T. R. Adam bemoaned the “mystification in this belief in the power of great paintings to communicate abstract ideas of beauty to the uninformed spectator.”81 After the war an official report on participation in the arts in Britain urged art museums to better serve their visitors. “The majority of their visitors do not know how to look at works of art and all too many walk around an exhibition and out again without having stopped to consider any one of the individual works…. Wellprinted labels and catalogues giving adequate information will help to arrest their attention.”82

But museum professionals held their ground. In 1945, Kenneth Clark, director of London's National Gallery, insisted that with works of art “the important thing is our direct response to them. We do not value pictures as documents. We do not want to know about them; we want to know them, and explanations may too often interfere with our direct responses.”83 A few years later, the Fogg Museum's director, John Coolidge, insisted: “The primary way to explain a work of art is to exhibit it.” “Let us isolate the object,” he urged, “let us be sure that it is at all times lit to the greatest advantage, and let us so arrange the gallery that the visitor can sit comfortably in front of it and lose himself in communion with the work of art.”84 Despite recent efforts to make museums more userfriendly and the introduction of audio guides and multimedia support in a select few galleries (notably African), attitudes to interpretation remain generally conservative. Note, for example, how relevant the following statement issued by the Cleveland Museum of Art in 1971 still is today: “The Museum's permanent galleries…are designed as quiet areas where the individual visitor can see and respond to the individual work of art. This personal encounter between the viewer and the object is the deep and particular satisfaction a museum offers. Explanatory gallery labels usually keep their text to a minimum to avoid intruding between the visitor and the work of art.”85

Education programs took root in art museums everywhere in the middle decades of the century, yet residual attitudes among directors and curators suggest that Low's description of their “moral quarantine” was scarcely an exaggeration. In the eyes of some, the public itself became a nuisance to be tolerated but not indulged. Take the case of Eric Maclagen, director of the Victoria and Albert Museum in the 1930s. When asked if his museum had become “a mere museum for connoisseurs and collectors,” he agreed it was a fair description “but for the insertion of the word ‘mere.’”86 A few years later he had this to say to a gathering of fellow museum professionals: “If we were to be entirely candid as to the view taken by museum officials with regard to the public I fear we should be bound to admit that there are occasions when we have felt that what is wanted might be described in the language of the cross-word puzzle, as a noun of three letters beginning with A and ending with S. We humour them when they suggest absurd reforms, we placate them with small material comforts, but we heave sighs of relief when they go away and leave us to our jobs.”87 And lest we dismiss such talk as after-dinner humor from an aloof British aristocrat, we find much the same relief expressed by John Walker, director of Washington's publicly funded National Gallery, as he anticipated the departure of the day's last visitors:

When the doors are closed a metamorphosis occurs, and the director or curator is transformed into a prince strolling alone through his own palace with an occasional bowing watchman accompanied by his dog the only obsequious courtier. The high vaulted ceilings, shadowy corridors, soaring columns, seemed to have been designed solely for his pleasure, and all the paintings and sculpture, those great achievements of human genius, to exist for no one else. Then, undisturbed by visitors, he experiences from time to time marvelous instants of rapt contemplation when spectator and work of art are in absolute communion. Can life offer any greater pleasure than these moments of complete absorption in beauty?88

If characteristic images of the Victorian museum show healthy crowds (fig. 11) seeking wholesome recreation, the twentieth-century curatorial ideal in the form of the “installation shot” (fig. 41) rids the gallery of visitors altogether, leaving the disembodied eye to roam freely without distraction.89 Curators and art critics customarily enjoy the privilege of seeing and reviewing new exhibitions and installations without the throngs who make those events so challenging for the average museum-goer.

Given that social history had found a natural home in the art museums of the Soviet Union and was preferred in the West by labor unions and leftist educators, is it any wonder that it had so little purchase with mainstream museum donors, trustees, and curators?90 And what support it had was washed away in the wake of World War II and the rise of the cold war, an era that sealed the ascendance of a universal conception of art in landmark exhibitions such as MoMA's Timeless Aspects of Modern Art (1948–49) and The Family of Man (1955). Where art had been reduced to propaganda under fascist and communist regimes, in the West it became the embodiment of individual freedom, and this freedom extended to the public to enjoy a museum's contents without interpretation, at least of a social nature. In art history graduate programs social art history experienced the same eclipse. At Harvard Paul Sachs's famed Museum Course was taken over by Jakob Rosenberg, who steered the program, and future curators, still further toward connoisseurship.

Though perhaps not intended, the triumph of silent contemplation in the art museum reversed the social activism of the 1920s and 1930s and lessened the appeal of museums for the uninitiated. In Britain, the 1946 report cited above found that museum attendance had dropped 25 percent in the previous twenty years and concluded: “[T]he numbers might be very much greater if the directors and their staffs were as interested in attracting and educating the public at large as they are in the specialist needs of students and connoisseurs.”91 One wonders if the same causes were behind a similar decline registered at the Metropolitan Museum over the same period, notwithstanding extensive educational programming. Theodore Low's 1948 report on the state of the field noted that the Met's visitors came disproportionately from the “upper circles” and that educational services at all art museums tended to be monopolized by the “upper layer of cultured residents,” hampering the efforts of educators to expand the public.92

Postmodernism: The End of Innocence?

It is a mark of how completely social activism had disappeared from museum discourse that its return in the 1960s in the context of broad social upheaval and looming financial crisis seemed radical and without precedent. Or perhaps it would be more accurate to say that while many education programs carried on as they had for decades and directors and trustees continued to believe they were serving their institutions and communities, the world beyond the museum had changed dramatically and many museums, especially those in urban settings, awoke to find themselves out of touch with social developments.

Social activism and protest directed at art museums on both sides of the Atlantic concerned public access, who went to museums and who did not, and why. In what ways could museums become more socially inclusive and responsive to the needs of the public? In 1966 the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu teamed with statistician Alain Darbel to write The Love of Art, a comprehensive analysis of participation in museum culture in France. Armed with carefully compiled empirical data, Bourdieu and Darbel argued (as others had done before) that the art museum public consisted overwhelmingly of the “cultivated classes.” In their broad demographic survey, 75 percent of visitors could be identified as belonging to the upper classes, against just 4 percent from the working classes. Bourdieu explained this social imbalance in terms of “habitus”—superior access to the codes of art appreciation and rituals of museum-going available to the upper classes through education and upbringing. Schooling had the potential to level the field—indeed, Bourdieu argued, it is the “specific function of the school…to develop or create the dispositions which make for the cultivated individual”—but if and when schools fell short, that left “cultural transmission to the family,” perpetuating “existing inequalities.”93 “There is nothing better placed to give the feeling of familiarity with works of art than early museum visits undertaken as an integral part of the familiar rhythms of family life,” he wrote.94 According to Bourdieu, museums helped maintain the status quo by assuming knowledge in visitors and failing to help the uninitiated make proper sense of what they saw; in so doing, they betrayed “their true function, which is to reinforce for some the feeling of belonging and for others the feeling of exclusion.”95

Bourdieu's critique inspired protests against museums during and after the Paris uprisings of 1968 and laid the ground for the opening of the populist Pompidou Center in 1977 (fig. 46).96 Across the Atlantic social ferment fueled similar protests at the major New York museums. As mentioned in chapter 1, various groups—including the Art Workers' Coalition, Women Artists in Revolution, the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition, and the Guerrilla Girls—called for greater representation of women and African Americans at all levels of museum life. In 1970 protesters crashed the annual meeting of the American Association of Museums to demand greater “democratization” of museums as well as an end to the Vietnam War and persecution of the militant Black Panthers. After heated debate, the conference concluded that museums, as collections of objects, “are not those organizations best suited to cope with the social and political concerns of the moment” but that at the same time “neither are [they], surely, doing everything they might to bring to bear their own special resources on what now shakes the peace of mind of their visitors.”97 To which Nancy Hanks, chair of the National Endowment for the Arts, responded: “I do not think we can any longer spend time discussing the role of the museum as a repository of treasures versus its public role. It simply has to be both.”98

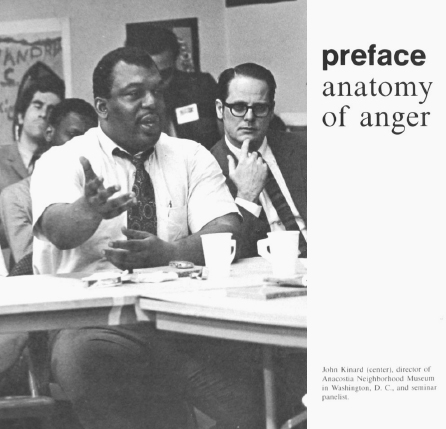

Bourdieu's critique of museums focused on making the high art of mainstream museums more accessible to a broader audience, but a second approach revived prewar ideas about validating popular culture and creating local museums responding to specific community needs. In France, “Ecomuseums” showcased regional popular culture across the country.99 In the United States, the Anacostia Museum opened in 1967 in a depressed area of Washington, D.C., under the aegis of the Smithsonian Institution, reviving the prewar concept of the branch museum. Led by John Kinard, Anacostia was run by members of the local community and focused on “social issues affecting its constituents and neighbors”100 but also on “Afro-American history and culture.”101 Kinard intended the museum to be a showcase for the “unique and creative…contributions of the black man to America.”102 The museum was conceived by the director of the Smithsonian Institution, S. Dillon Ripley, who wanted to extend the museum's benefits to “all our people, those…who most deserve to have the fun of seeing, of being in a museum,” especially in light of the crisis that gripped many U.S. cities, including Washington.103 Though Ripley was himself thoroughly at home in the corridors of high culture (he felt no “generation gap” separating him from the great masterpieces of the past, for example), he understood that mainstream art museums, because of their continued dependence on the “dominant forces in the community, the civic boosters and the wealthy,” had neglected various constituencies, including artists and art historians, but above all “the poor people, products of a self-perpetuating disease found in our cities.” He continued: “Such people were neither objects of pride to our civic boosters nor particular objects of concern to our aggressive middle class who had responded to the urge to better themselves. If the art museum had become a symbol only to the community leaders and those conditioned to the concept of getting ahead, who realized that art was a subject of elitist veneration and that culture should be subscribed to and taken in doses like vitamin pills, then of course it had failed.”104

93. John Kinard at the Seminar on Neighborhood Museums, Brooklyn, New York, 1969. From Emily Dennis Harvey and Bernard Friedberg, A Museum for the People (New York: Arno Press, 1971).

The success of Anacostia gave rise to a remarkable Seminar on Neighborhood Museums held in Brooklyn in 1969 (fig. 93) at which the frustrations of marginalized urban minorities came to a head. A succession of speakers, including Kinard, denounced the failure of mainstream museums to understand or grapple with the needs and interests of local communities. Also present was Allon Schoener, director of the visual arts program of the New York State Council on the Arts and organizer of the Met's Harlem on My Mind exhibition. Challenging the social relevance of mainstream art museums, Schoener used Cleveland, whose director, Sherman Lee, had been the most vocal critic of the Harlem exhibition, as his example:

I think there is another measure (other than fine collections) which has to be applied to institutions like the Cleveland Museum of Art—and that is, how does this museum relate to the community? The Cleveland Museum sits on an idyllic island with only one entrance. It's surrounded on three sides by one of the worst black areas in the United States. Within the last few years, the Cleveland Museum has obtained a bequest of $20 million, and the $20 million is going to be used to build a new building, buy more collections—and it isn't really doing anything in relationship to the community that is right at its doors. How can major cultural institutions in our society today be so oblivious?105

Representatives from major museums were largely absent from the event, and those who came offered little in the way of defense. Among the conclusions summarized by one of the organizers, Emily Dennis Harvey, were the need to reexamine “fundamental questions about art and culture, about their function in a community, what a museum is and what its function should be” and the “realization of the extreme difficulty of communication between members of the museum establishment and representatives of militant minority groups.”106 The museum establishment had little interest in changing the fundamental nature of the art museum, or in addressing the social issues that surrounded them. In response to Thomas Hoving and calls for social relevance, most mainstream directors reiterated a commitment to their collections and left it to the educators to cope with the growing audiences asking to be heard. As early as 1961, the Guggenheim's first director and former MoMA curator, James Johnson Sweeney, railed against the rise of education programs and hoped his colleagues had “the courage to face the fact that the highest experiences of art are only for the elite who have ‘earned in order to possess.’”107 Some years later in the wake of the Harlem brouhaha, John Walker, safely ensconced across the Potomac from Anacostia at the National Gallery, bemoaned the pursuit of “relevance” and hoped the future would return museums to “their original mission, which once was to assemble and exhibit masterpieces.”108 Though by hosting the Mona Lisa at the National Gallery in 1963 he was responsible for one of the most popular exhibitions of all time, Walker was baffled by the crowds and continued to believe his primary responsibility was to his collection and the small minority who really understood it: “I was, and still am, an elitist, knowing full well that this is now an unfashionable attitude. It was my hope that through education, which I greatly promoted when I became a museum director myself, I might increase the minority I served; but I constantly preached an understanding and a respect for quality in works of art…. The success or failure of a museum is not to be measured by attendance but by the beauty of its collections and the harmony of their display.”109 In response to the misguided populists, Sherman Lee in Cleveland also took issue with the idea of the museum as instrument of mass education or social action. “Merely by existing—preserving and exhibiting works of art,” he wrote, “it is educational in the broadest and best sense, though it never utters a sound or prints a word.”110 He supported education programs so long as they respected the silence and integrity of the visual experience of great art, and consequently he also rejected the hoopla of blockbuster exhibitions, fund-raising cocktail parties, and audio tours, suggesting that such activities, if necessary at all, should be held at a separate site, like a branch museum.111

The 1970s witnessed a deepening divide between director-curators and educators in art museums. A 1984 report Museums for a New Century noted that an unparalleled movement in the direction of “democratization,” access, and involvement “in our nation's social and cultural life” over the previous fifteen years had done nothing to close the gap between education and curatorial departments or lessen the tendency to keep audiences in the dark about choices affecting exhibition programming and the collection.112 However, external forces were already working to foster closer collaboration between the two and to raise the profile of “visitor services.” Even as Allon Schoener bemoaned the lack of community involvement at mainstream art museums, he correctly predicted that change for the better would come from funding sources. “The problem museums are facing today, I think, is one of changing patronage,” a shift from reliance on “a few billionaires” to businesses and government agencies that, as a condition of funding, would ask probing questions: “Who is being served by the money that is being spent? How many people are going to experience something as a result of this? Where is the money going to be used?”113 Schoener recognized that museums were entering a new age of accountability, in which visitors would begin to matter as much as the permanent collection.

Pressure to know who visited art museums and who did not, and why, prompted a surge in audience research and evaluation that continues to this day. The museum literature is now rich in “easy-to-understand” guides to “designing and conducting your own visitor survey from start to finish”; helping “museum staff understand their clientele and their interactions with them”; “assessing the impact of exhibitions”; investigating “how people learn, their understandings, attitudes, and beliefs”; and so on.114 Audience surveys have become a staple of all museums, but especially those dependent on visitor revenue or public or foundation grants that come with social desiderata. Perhaps the strongest—or at least most public—example of conditional funding comes from the United Kingdom, where under the Labour government of Tony Blair national museums were asked to undertake serious diversity reviews as a condition of continued state support. Major museums were even given minority visitation targets (British Museum, 11 percent of total admissions; Tate Gallery, 6 percent, etc.).115 Though such targets are somewhat arbitrary and impractical (how are minorities to be counted?), the point behind them has been taken to heart by museums in Britain.116 Similar expectations now accompany many grants-in-aid from private and public funding agencies elsewhere.

In addition to external pressure to monitor and diversify audiences, internal pressure to generate more revenue has equally motivated private museums to find out more about who goes to art museums and who does not. Surveys help to develop larger and more loyal audiences, which mean more income. Where revenue is the driving force behind visitor evaluation, the size of the audience matters more than its color or ethnic diversity. Knowing your audience means knowing what it likes and is willing to pay for in the way of programs and ancillary services. The line between visitor surveys and marketing blurs.

It was recognized long ago that temporary exhibitions were a most effective audience enhancement tool, but from the 1970s the blockbuster became a way of life at museums in search of more visitors and money.117 The overlap of exhibition programming, audience enhancement, and revenue growth may be clearly seen at Boston's MFA in the late 1970s, when the need to impose admission charges (for the first time since Gilman's day) to offset mounting operating costs resulted in significant declines in attendance and prompted a sudden need to program special exhibitions the public was willing to pay for. Visitors responded in record numbers, and the MFA, like many other museums, has been dependent ever since on a steady diet of special shows to keep people coming. To house the exhibitions and ancillary services, museums embarked on extensive physical expansion. I.M. Pei's West Wing at Boston, opened in 1981 (fig. 48), houses functions—special exhibition spaces, multiple restaurants, a cloakroom, bathrooms, a bank machine, an ever-expanding shop, and an information desk—whose aim is to entice visitors and keep them entertained. Should we be surprised that the West Wing also houses the education department and school reception area? Where once architecture was criticized as a barrier to public use, new buildings have become crucial attractions in themselves. Pei's Boston wing was hailed as a “temple of cultural democracy” when it opened, and during the 1980s his high-profile additions to the National Gallery in Washington (East Wing) and the Louvre in Paris (fig. 47) helped to redefine the art museum as a multipurpose leisure destination and to greatly increase attendance.118 More recently, Calatrava's Quadracci Pavilion (fig. 52) has similarly transformed Milwaukee's old art museum. The new wing does nothing to enhance the permanent collection, but it provides much-needed space for blockbusters, commerce, school and group visits, and so on, in addition to an exciting new destination for locals and tourists alike.

At the end of the 1960s, the anthropologist Margaret Mead recommended that museums invest in shops, restaurants, and other amenities in an effort to combat their “snobby” profile and “welcome those people unaccustomed to the way of seeing and being of museums.”119 The advent of new programs and amenities has certainly increased visitation numerically, but it is less clear that audiences have expanded in ways Mead and others wished. As visitor numbers began to rise early in the 1960s, Rudolph Morris wondered whether larger attendance would also mean “a breakthrough to social classes formerly not affected by the existence of art museums.” He predicted that further increases were likely to be among “individuals of higher socio-economic status and better educational background.”120 According to Alan Wallach, Morris was largely correct: recent gains in audience size at art museums are the product of a swelling population of the educated and affluent whose appetite for art has been whetted by expanding university curricula and television (Kenneth Clark, Sister Wendy, etc.).121 In other words, as the educated population increases, so does the public for art museums; but museums still have difficulty reaching the underprivileged. The poor and marginalized people interviewed by Robert Coles many years ago who knew instinctively that art museums were “for other people, not for us” would have little reason to think differently today.122