5 COMMERCIALISM

Perhaps no development in the art museum of the last half-century has been more dramatic or controversial than the increase in commercialism, by which I mean the expansion of museum shops, the rise of the blockbuster exhibition and corporate sponsorship, and the influx of marketing and fund-raising personnel. A time traveler from the 1950s would surely be astonished to discover that it is now possible in our museums to eat (and eat well), shop, see a film, hear a concert, mingle at “singles night,” and attend a corporate function or wedding reception without seeing a single work of art, or to globe-trot from one museum to another and experience a seemingly unending round of blockbuster exhibitions, each accompanied by widespread advertising, a dizzying array of more or less art-related products for sale, and bundled package deals from airlines and hotels. Armed with sophisticated marketing and PR staff, museums have been working hard to shed their image as stuffy repositories. In London in the early 1990s Saatchi & Saatchi caught the public eye with an ad that described the Victoria and Albert Museum as “an ace caff with quite a nice museum attached.” In 2000 the venerable Worcester Art Museum in Massachusetts launched a membership drive aimed at younger visitors called “Friends of Steve” that used an image of the museum's founder, Stephen Sainsbury III (1835–1905), dressed in sunglasses, goatee, and a backward-turned baseball cap(fig. 95). The brochure asked: “Would you like a place to socialize with your contemporaries? Do you enjoy great parties and making new friends? Are you in your twenties or thirties? Worcester Art Museum's newest membership category is for you!” In New York the Guggenheim's Thomas Krens ruffled conventional feathers by suggesting that the successful twenty-first-century museum should include—besides a strong collection of art—a great building, multiple special exhibitions, shops, and eating opportunities (see below).

95. “Friends of Steve” marketing flier, Worcester Art Museum, ca. 2000.

Thanks to such initiatives art museums have never been more popular. Attendance is robust and special exhibitions are routinely congested, with some staying open overnight to accommodate the crowds. Once-sleepy shops stocked with postcards and scholarly catalogs have become attractive shopping destinations with satellite outlets and catalog-Internet operations. Many museum restaurants boast fine cuisine and merit culinary reviews. Despite the signs of success and visitor satisfaction, many in the art world have been disturbed by recent trends. Though on some level everyone in the art world benefits from the increased popularity of museums, a good number of academics, art critics, and museum professionals fear the erosion of the museum's integrity and scholarly profile through a “dumbing down” of standards in pursuit of larger audiences and enhanced revenue streams. Those critics liken the new museum to theme parks and shopping malls in which the viewing of art seems like an afterthought.

Press coverage of the art museum's metamorphosis has shifted over the years from wry observation to undisguised contempt. “Glory Days for the Art Museum,” declared the New York Times back in 1997: “It's cheap. It's fast. It offers great shopping, tempting food and a place to hang out. And visitors can even enjoy the art.”1 Another Times article a few weeks later announced: “This Isn't Your Father's Art Museum: Brooklyn's Got Monet, but Also Karaoke, Poetry and Disco.”2 An airline magazine informed weary travelers: “No longer the nation's attic, museums are now the places in town where lots of things happen.”3 But within a few years frontline journalists covering the art world had grown tired of the distractions. “What do art museums want?” asked Roberta Smith in the Times in 2000, since “it increasingly seems that they want to be anything but art museums.” “Don't Give Up on Art,” she pleaded.4 A year later Smith's colleague at the Times, Michael Kimmelman, chimed in that “museums are at a crossroads and need to decide which way they are going. They don't know whether they are more like universities or Disneyland, and lurch from one to the other.”5 Four years later Kimmelman was angry: “Museums are putting everything up for sale, from their artwork to their authority. And it's going cheap.” “Money rules,” he added, “and at cultural institutions today it seems increasingly to corrupt ethics and undermine bedrock goals like preserving the collection and upholding public interest.”6

Alarmed by the drift away from traditional values within their own institutions, a group of leading museum directors in the United States came together early in the new millennium to insist on the need to demonstrate “clear and discernible” differences between art and entertainment and a sharper contrast between the museum's activities “and those of the commercial world.”7 In their opinion, nothing less than public trust in the institution was at stake. As Philippe de Montebello put it: “It is clearly by differentiating ourselves from all manner of entertainment that we maintain our integrity.”8

Despite the dire warnings, the directors offered no easy solutions to the problem; nor did they acknowledge the extent of their own involvement in the situation they described. In an ideal world, most museum directors would do away with glitzy shops and blockbusters, marketing personnel and corporate sponsors. But in the real world, only extremely well-endowed museums (e.g., the Getty or Menil) can survive without them. Also missing from arguments against commerce and entertainment is concrete evidence of public disaffection. What evidence do museums have that public trust is weakened by blockbusters and corporate sponsorship? Is there reason to think the public would prefer museums without shops and restaurants, or to the contrary are they now both crucial ingredients of the museum experience? Are museums and commerce incompatible? The purpose of this chapter will be to survey the art museum's complex historical relationship to commerce, industry, and money. Because no two institutions are the same and funding patterns differ from one country to the next, this account can do no more than outline general trends and pressing theoretical issues.

Art and commerce have long enjoyed an uneasy relationship. Artists have always worked for a living, but beginning with the creation of art academies during the Renaissance they have projected an image of indifference to material concerns. The purpose of early art academies was to elevate the fine arts of painting, sculpture, and architecture above manual labor and the base concerns of the marketplace. In concert with princely patrons who transformed material wealth into symbolic capital through artistic patronage, artists of the early modern period distanced themselves from the artisanal crafts of the guilds by asserting the intellectual, nonmaterial value of their work. Academic art theory worked to ally the “high” arts with poetry, philosophy, and the pleasures of the imagination and to relegate the decorative arts to a lower plane of ornament, craft, and utility. Within the high arts, academies established a hierarchy of genres that deliberately inverted market forces by privileging “history painting” (the depiction of noble human actions) above the more popular and lucrative categories of landscape, still life, and portraiture. From the seventeenth century, the Royal Academy in Paris prohibited its members from engaging in overt commercial activity (advertising, setting up shop, etc.); as recipients of royal patronage and pensions, tax exemptions, exclusive exhibition rights, and royal accommodation, artists were liberated (in theory at least) from the normal circuits of economic exchange. Strictures and privileges may have been weaker in other countries, but in general membership in a fine arts academy implied genteel status and a corresponding distance from money. Sir Joshua Reynolds began his inaugural “Discourse” (1768) to the newly founded Royal Academy in London, for example, by insisting that its members ignore “mercantile” concerns and concentrate instead on the “Polite Arts.”9 What he termed the “inferior ends” of commercial design were consigned to separate organizations established alongside the fine arts academies—in London the Royal Society of the Arts (1753) and in Paris the École Royale Gratuite de Dessin (1767). According to nineteenth-century stereotypes, artists took to living in garrets and wore their lack of material success as a badge of honor.

At the same time, however, governments invested in the fine arts in good part for economic reasons. Producing superior artists glorified the nation, but it also produced objects that could be sold abroad; indeed, one measure of superior art was its standing among foreign patrons. Notwithstanding theoretical distinctions between “high” and “low” art, in France established academy artists produced tapestry and porcelain designs for the royal Gobelin and Sèvres factories, both of which were admired across Europe for the quality of their goods. “Art can be looked at from a commercial point of view,” wrote C. L. von Hagedorn of the Dresden Academy in 1763; “while it redounds to the honour of a country to produce excellent artists, it is no less useful to raise the demand abroad for one's industrial products.”10 Hagedorn had in mind the growing international competition in china and textiles, and he understood that commercial success in the decorative arts depended on high standards of artistry, which it was the function of academies to provide. Moreover, economic necessity forced many artists, Reynolds included, to pursue the lower genres and contribute to the production of decorative arts and commercial engraving.

Given that the first museums were commonly associated with fine arts academies, it is hardly surprising that they were dedicated from the first to high art. Yet here, too, ambiguities may be found. Witness the early Louvre. Disregarding the art market, which prized portraits and small decorative pieces for the home above all, the Louvre aimed to promote serious history painting and sculpture and thereby demonstrate the superiority of the French school and its academic system. In the 1780s the state commissioned patriotic statues of French heroes and grand moralizing paintings from David (the Oath of the Horatii and Brutus) and his colleagues to line the walls of the museum. Yet each of those paintings and sculptures was also intended to serve as a model for commercially available reproductions in tapestry and (on a reduced scale) in porcelain. And at least one Sèvres piece—a magnificent “Grand Vase” designed by the sculptor Boizot—was created especially for display at the Louvre to advertise the combined strengths of French art and manufacture.

When the Louvre opened definitively in 1794 at the height of the French Revolution it featured only Old Master paintings and ancient sculptures; the decorative arts, as a luxury commodity and staple of aristocratic interiors, were banished. The example of the Louvre did much to define the art museum as an exclusive space of authentic, highart masterpieces. Separate museums were created in and around Paris for the applied arts and modern French painting and sculpture.11 The Louvre hosted occasional exhibitions of new inventions and machines from the late 1790s, but they never compromised the museum's identity as a bastion of high art.12 Though the Louvre was “pure” in its contents, the commercial advantages it brought to France were not ignored. For ideological and economic reasons, foreign visitors were always vital to the museum. The Louvre “must attract foreigners and fix their attention,” in the words of the revolutionary minister who supervised its creation.13 The many thousands of visitors who flocked to Paris during peaceful interludes to see the Louvre commented on the inflated prices of food, accommodation, and transportation in central Paris. A British banker who made the trip in 1802 noted: “[T]hese pictures and statues must prove a mine of wealth to Paris, as all the world will go to see them.”14 Visitors bought catalogs offered for sale at the door, and from 1797 on they could also buy engraved reproductions of key works produced at the Chalcographie Nationale.15 In the second half of the nineteenth century, photographs and postcards replaced engravings, and competition among firms for the lucrative tourist market at the Louvre was intense.16 (The Chalcographie survived, ironically, by continuing to provide more expensive and “artistic” interpretations of original works of art.) From an early date the Louvre and other museums that followed its lead participated in and profited from the commercial reproduction of their masterpieces.

Utilitarian Commerce

As art museums evolved from princely collections to state-run institutions with a public purpose, economic justifications soon followed. In addition to bolstering national or civic pride and educating young artists, museums contributed to the elevation of taste among the general public—a matter of direct economic consequence, since improved taste made for better producers and consumers of art and manufactured goods. In the first decades of the nineteenth century the connection between the public display of high art and improved standards of design surfaced frequently to support investment in museums in Paris, London, and Berlin.17 In 1835 a Select Committee of the British Parliament, concerned that native industries suffered in the world marketplace because of inferior design, launched an inquiry “into the best means of extending a knowledge of the arts and of the principles of design among the People (especially the Manufacturing Population) of the Country.” A year later it concluded:

In many despotic countries far more development has been given to genius, and greater encouragement to industry, by a more liberal diffusion of the enlightening influence of the Arts. Yet to us, a peculiarly manufacturing nation, the connextion between art and manufactures is most important; and for this economical reason (were there no higher motive), it equally imports us to encourage art in its loftier attributes; since it is admitted that the cultivation of the more exalted branches of design tends to advance the humblest pursuits of industry, while the connextion of art with manufacture has often developed the genius of the greatest masters of design.18

After 1837 schools of design opened in London and the provinces for the purpose of training artisans. At the same time it became clear that consumers also needed training, and the means to that end were public exhibitions. Temporary exhibitions of domestic wares in Paris and London in the 1840s prompted Sir Henry Cole to organize a comprehensive international exhibition of manufactured goods, which resulted in the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London. In terms of its scale and drawing power it had no precedent. Over a five-month period, some six million visitors paid to see a stupendous array of one hundred thousand objects from around the world. Sir Joseph Paxton's building of glass and iron, known as the Crystal Palace, was itself worth the price of admission. Recreation at once useful and entertaining afforded to so many ideally met the needs of an emerging industrialized society. The overlapping economic and social benefits were plain to see, according to one report: “Magnificent was the conception of this gathering together of the commercial travelers of the universal world, side by side with their employees and customers, and with a showroom for their goods that ought to be such as the world has never before beheld.”19 So successful was the Great Exhibition and so contagious was Cole's vision of improved technology and design leading to peace, progress, and class harmony that for the next century and more Western nations competed for the right to host similar fairs. Civilization and progress, as defined by the expositions, required the marriage of industry and art, the ability to both produce and appreciate, and therefore consume, good design.

The ability of international exhibitions to stimulate taste and competition was limited, however, by their short duration, irregular occurrence, and shifting location. What was needed, as Horace Greeley put it at the time of the New York World's Fair in 1853, was a permanent “art and industry show-house…a broad national and cosmopolitan platform whereon genius or ingenuity may at once place its productions and obtain the highest sanctions.”20 Fully in agreement, Henry Cole created the South Kensington Museum in 1857, the first museum dedicated to the applied and decorative arts. Consistent with the twofold purpose of the Great Exhibition, to instruct and entertain, Cole's museum classified its contents (some of which had come from the Crystal Palace) by material and process (metalwork, glass, textiles, etc.), the better to serve the artisan and designer, yet also catered to a broad public by displaying domestic, commercially available objects, adopting evening hours, and opening a restaurant.

Just as the Great Exhibition spawned dozens of world's fairs, so the South Kensington Museum was imitated throughout Europe and the United States in the 1860s and 1870s, for each metropolitan center needed its own permanent design resource.21 Dedicated applied arts museums became especially popular in the industrialized countries of northern Europe, beginning with Germany, Austria, and France, while in the United States new museums sought to combine the virtues of the high-art museum and the kunstgewerbe type. The founding charter of New York's Metropolitan Museum, for example, spoke of “encouraging and developing the study of the fine arts [and] the application of arts to manufacture and practical life,…furnishing popular instruction and recreation.”22 The Met's first director, General Cesnola, argued that the “practical value of the American museum” entailed that it become “a resource whence artisanship and handicraft of all sorts may better and beautify our dwellings, our ornaments, our garments, our implements of daily life,” while also providing entertainment to the “casual visitor.”23 In like spirit, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts adopted “Art, Education, Industry” as its motto.

Over time, however, as discussed in chapter 1, the South Kensington philosophy came under fire on both sides of the Atlantic for failing to produce any demonstrable improvement in design standards or public taste. Manufacturers did not send workers to study in the museum. William Morris, among others, doubted whether a collection of artifacts could inspire new art. On a deeper level, he and John Ruskin rejected the notion that industrial production could yield good art and design, for in their eyes machine manufacturing violated the dignity of human labor.24 Instead of progress and higher living standards for all, industrial society had produced demeaning work routines, shoddy products, and urban slums. Meanwhile, the school of design affiliated with the museum had degenerated into a second-rate art school “for the delectation of shoals of female amateurs, and for the turning out of a cartload of mostly mediocre artists of both sexes.”25 What was worse, according to the painter Herkomer, it had led young artisans astray, filling their heads with high-art ambitions and diverting them from the “dignity of their craft.”26

Art and Antimaterialism

In the wake of growing mechanization and what Ruskin termed the “fury of avaricious commerce,” art museums became more a refuge from than a handmaiden to progress and modernity.27 For the likes of Ruskin, Morris, and Matthew Arnold, art and culture were the source of morality, transcendent beauty, and humanity, and as such an antidote to the dehumanizing consequences of capitalism and industry. Ruskin's experimental utopia, the Guild of St. George, banned machinery and common currency; as we have seen, his own museum near Sheffield (fig. 10) was devoted to the nonutilitarian education and delight of factory workers. The equally idealistic Arts and Crafts movement founded by Morris and his followers attempted to revive handicrafts and the premodern guild system. Arnold preached the widespread dissemination of “sweetness and light” as a remedy for poverty, ignorance, and soulless materialism. By century's end, the equation of material progress and civilization, and with it South Kensington's forced marriage of art and industry, had lost much of their credibility.

At international expositions the fine arts grew more autonomous. Following their happy union at the Philadelphia World's Fair of 1876, art and industry experienced a trial separation at the 1893 Columbia Exposition (see chapter 1), and then a complete divorce at Chicago's Century of Progress Fair in 1933, where the fine arts exhibition was held off-site at the Art Institute and, contrary to the fair's spirit, celebrated the past instead of the future.28 Similarly the Masterpieces of Art exhibition at New York's 1939 World of Tomorrow fair was decidedly antimodern, and even anti-American, in its focus on the “great epochs in the art history of Europe, from the beginnings of easel painting, about 1300, until the time of the French Revolution which marked the beginning of modern painting.”29 In the decades following the landmark Columbian Exposition, antimodern temples of art arose in urban parks (often in cities that had just hosted world's fairs, such as Buffalo, St. Louis, and San Francisco) as respites from city life. The selfsame industrialists and merchants whose products filled the exhibition halls relied on the collecting of (preindustrial) art and the patronage of classical museums to disprove Arnold's assertion that the United States had no culture.

The strongest proponent of art's divorce from utility and commerce was Benjamin Ives Gilman in Boston. At the new Museum of Fine Arts, opened in 1909, the merger of art and industry that had characterized the first museum disappeared and, as we have seen, was replaced by a Grecian temple dedicated to aesthetic contemplation of fine art (figs. 33–34). When Gilman stated that art museums were not primarily educational in purpose, he meant that they were not utilitarian and had no business competing with colleges and schools in the training of craftsmen or scholars. Heavily indebted to Arnold and Ruskin, and hoping to rebut charges of American philistinism, Gilman argued that art was not a means to an end but an end in itself.30 Because art's true utility resided in its transcendent aesthetic value—that is, its practical uselessness—Gilman insisted that art museums should reject associations with money and commerce, beginning at the front door with the abolition of admission fees: “For a museum of art to sell the right of admission conflicts with the essential nature of its contents.”31 Gilman continued: “Money and fine art are like oil and water: differing and even mutually repelling in essence. Art is necessarily joined with its ill-assorted companion in origin and generally in fate. Artists must make a living, and collectors inevitably compete for their achievements. A work of art is rescued from this companionship with money when it reaches a museum. Yet the divorce is not complete while money is demanded as the price of its contemplation. The office of a museum is not ideally fulfilled until access to it is granted without pay.”32 He also deemed publicity inappropriate because it made a museum seem too much like a commercial enterprise, and because a museum's effectiveness should not be measured in terms of visitor numbers, an increase in which was publicity's chief goal. Museums would not be more “effective because they gather crowds,” he insisted.33 For Gilman, visitor numbers and revenue were irrelevant and even contrary to the aesthetic experience of the individual beholder.

To suggest that art museums completely washed their hands of industry and commerce in the early 1900s would be incorrect, however. Gilman's principled rejection of utility, money, and publicity and his insistence on the integrity of aesthetic experience would become commonplace in the second half of the century—indeed, his ideals retain their currency today—but at other prominent museums the situation was more complicated. Though under attack from the late nineteenth century on, the utilitarian museum philosophy did not so much disappear as change focus. At museums dedicated to the applied arts, attention shifted from training artisans to producing informed consumers in the belief that refined taste would heighten demand for better products and thereby force improved design standards through a market form of natural selection. Museums in Germany were among the first to replace an emphasis on materials and techniques with contextual installations and period rooms in order to “raise the general popular taste” by demonstrating “the living connection of things.”34 By the 1920s Charles Richards could assert unequivocally “that the first and highest purpose of industrial art collections is the education of public taste.”35

In the United States, where commercial interests and their denial wrestled with each other in the hearts and minds of museum boosters, the first decades of the twentieth century witnessed tensions between a populist, consumer-oriented utilitarianism and Gilman's aesthetic philosophy. The pragmatic strain in North American museum thinking had deep roots. In a talk entitled “Museums of the Future,” given in 1889, George Brown Goode of the Smithsonian declared: “The museum of the past must be set aside, reconstructed, transformed from a cemetery of bric-a-brac into a nursery of living thoughts. The museum of the future must stand side by side with the library and the laboratory…as one of the principal agencies for the enlightenment of the people…adapted to the needs of the mechanic, the factory operator, the day laborer, the salesman, and the clerk, as much as those of the professional man and the man of leisure.”36 Goode's utilitarian ideals were embraced by John Cotton Dana at the Newark Museum, opened in 1909 at the heart of an industrial, immigrant-rich city. Indebted to Goode, but also to Thorstein Veblen, who viewed collections of art less as an antidote to capitalist excess than as a fetishized product of it, Dana defined his own museum in marked contrast to everything Gilman's art museum stood for. Where the latter housed expensive and unique treasures imported from Europe, Dana's museum promoted the everyday, often mass-produced products of local industries. Realizing that the Arts and Crafts movement had done little more than create expensive commodities for the moneyed classes, he embraced “articles made by machinery for actual daily use by mere living people,” not excluding shoes and shop signs, table knives and hatpins.37 Given the expansion of industry and mechanization, the “useful” museum should embrace the machine age and enable the public to master its possibilities. Dana saw his museum as an active learning center located at the hub of a working community rather than a passive receptacle of artifacts isolated in a distant park. To better serve area businesses, workers, and consumers, he recommended museum advertising in all forms. And Dana was at his most provocative when he acknowledged the “frankly commercial” nature of his enterprise while mocking the bourgeois discretion of “gazing museums” full of costly treasures. “Commerce is not sinful,” he wrote. “It exudes no virulent poison which is harmful to the elevated souls of art museum trustees, administrators and visitors.”38 If we were to judge the Newark Museum by its contents alone it would hardly merit discussion in a book on art museums, but it belongs here because art museums served as a point of departure and contrast for everything Dana did.

If Dana and Gilman represented opposite poles of museum theory and practice, a number of prominent art museums, including the Brooklyn Museum, the Met, and MoMA, searched for middle ground, promoting design and experimenting with strategies pioneered in the commercial sphere, notably in department stores, which for much of the twentieth century drew comparisons with museums as popular urban destinations.

Department Stores and Design

When it came to molding public taste with respect to domestic products, museums were soon surpassed by department stores, which by the 1920s had assumed a central place in the life and economy of North American and European cities. Like museums on the South Kensington model, department stores, often built of modern materials (steel, glass, terra-cotta) and organized by materials (glassware, linen, etc.), shared an origin in world's fairs. Though Henry Cole imagined that museums would make up for the impermanence of fairs, museums proved more interested in the past than the present, and the role of permanent bazaar was taken over by the store, which offered the public a constantly revolving spectacle of novel products and the appeal of instant consumer gratification. Motivated by profit, store managers exploited novel advertising and retail strategies, including seductive shop window displays, to seize the public's imagination and rival the museum as a source of visual delight and instruction. Stores invested in aesthetics and consumer psychology because they helped to sell products, and museums came to realize they had something to learn from their commercial cousins.39 Though museum men and store managers were quick to insist on the differences between their goals and functions, they nevertheless acknowledged common concerns. Jesse Strauss of Macy's, for example, stated categorically that “a successful store is not a museum” but then sounded like a curator in endorsing “clean-line modern architecture” and the avoidance of visual distractions in order to focus attention on products displayed.40 With equal ambivalence, Carlos Cummings, director of the Buffalo Museum of Science, titled a comparative study of museums, fairs, and merchandisers East Is East and West Is West (1940), as if never the twain should meet, yet proceeded to liken museum displays to “modern high pressure advertising” used “to sell a customer an object of real service to him,” and to urge his museum colleagues who were in search of new display strategies to examine “high-class shop windows in almost any big city.”41 What museums and stores had to “sell” might have been quite different, but the means of engaging their publics could be the same.

In the context of a rapidly expanding modern consumer society, a society hungry for material comforts as well as culture, museums and department stores enjoyed a degree of collaboration that today seems surprising. For an extended period in the 1910s, 1920s, and 1930s there was significant overlap between the spheres of retail and high culture. Store windows were likened to picture frames, and significant artists, architects, and designers—Archipenko, Georgia O'Keefe, Frederick Kiesler, Norman Bel Geddes, Raymond Loewy, Lescaze and Howe, and Mies van der Rohe—lent their talents to the enhancement of commercial spaces.42 Department stores displayed and sold contemporary art, often of the highest quality, and many major patrons of North American museums—George Hearn, Benjamin Altman, Samuel Kress—were department store magnates. Classes and clubs for businessmen, store buyers, and salespeople became commonplace at museums on the East Coast and in the Midwest.43 In the hope of attracting more visitors to his downtown branch museum in Philadelphia (fig. 92), Philip Youtz consulted with local merchants about marketing strategies and local shopping patterns. He learned that shopping picked up toward the weekend and that constant novelty was needed to keep customers coming back, which argued for closing museums early in the week and offering temporary exhibitions and programming.44

As we might expect, Dana was among the first to see the department store's potential and was typically polemical in his views: “A great city department store of the first class is perhaps more like a good museum of art than are any of the museums we have yet established,” he wrote in 1917.45 For Dana, “good art” was not limited to the contents of art museums but could be found “wherever the interested and intelligent open their eyes and find color, form, line and light and shade.” That included the shop windows of New York City, where millions of ordinary consumers unwittingly received daily lessons in art, design, and color harmony. “In fact, these millions of shoppers are building their own art content better than they know!”46 If anything, the traditional art museum impeded such learning by insisting on its own hermetic values, and one of Dana's goals at Newark was to liberate ordinary people to see beauty in their everyday environment. Among his many remarkable display initiatives were cases that featured everyday products that could be had for fifty cents or less (fig. 13). In conjunction with department stores, the useful museum would help to prepare the populace for the brave new world of industry and commerce. Significantly, the new building for the Newark Museum (opened in 1926) was the gift of local department store owner Louis Bamberger, who supported the museum over many years.

Perhaps the most interesting, and in hindsight most surprising, example of collaboration involved the Metropolitan Museum in New York. From 1917 through the 1930s, the Met hosted annual exhibitions of contemporary craft and industrial design together with programs for people involved with commerce. Richard Bach was hired as an associate in industrial arts and put in charge of the exhibitions. He described himself “as a sort of liaison officer between the Museum and the world of art in trade,” assisting “manufacturers and designers from the standpoint of their own requirements.” Visiting shops and workrooms and staying abreast of market trends, he aimed “to visualize trade values in museum facilities and thus help manufacturers towards their own objectives.”47 Working between designers and manufacturers on the one hand and the consuming public on the other, the Met mimicked the department store in obvious respects. As Richard Bach wrote in the trade magazine of Chicago's Marshall Field's department store: “Manufacturers, merchants, and the Museum of Art together seem to form a new magic circle of industry, a continuous and certain means of bringing art into the furnishings and clothing and other homely factors of daily life.”48 The president of the Met, no less, sounded like a Dana disciple when he told a gathering of business executives: “[Y]ou can all be missionaries of beauty. Your influence is far greater than that of all museums. You are the most fruitful source of art in America.”49 Also in 1917 the Met hosted a session of the American Association of Museums conference devoted to “Methods of Display in Museums of Art,” which included presentations by a representative from the Gorham Corporation and Frederick Hoffman, a well-known window dresser at Altman's.50 Ten years later, in 1927–28, the Met joined forces with Macy's to organize the “Art-in-Trade” expositions featuring contemporary room settings installed and furnished by major designers. Similar in appearance and purpose, the exhibitions at both venues attracted crowds that reached modern blockbuster proportions: some 250,000 people saw the Macy's 1928 trade show, and 185,000 went to see the Met's exhibition a year later.51 Collaboration gave the Met an opportunity to “compare the attractive force of a purely artistic demonstration against a background of business life with the results of similar displays in the atmosphere of the museum.”52 By all accounts the museum benefited more from the exchange, for, as Dana and others implied, there was nothing to compare with the visual allure of the modern shop window.

96. John Wellborn Root, “Woman's Bedroom,” from the exhibition The Architect and the Industrial Arts at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1929. Image © Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

The 1927 Macy's exhibition was organized by the well-known theatrical set designer Lee Simonson. Simonson, a Harvard graduate equally at home on Fifth Avenue and among the artists and impresarios who pioneered the modern movement in the United States, also had strong opinions about museums. In his view, what theaters and department stores had in common and museums sorely needed was “showmanship.” As early as 1914 he had complained that museums were “dreary asylums” owing to overcrowded and unimaginative installations. “You make a museum with fifty masterpieces, not with five hundred,” he wrote, and you display those fifty masterpieces with flair.53 Twenty years later he could still complain: “Our museums remain ineffective very largely because the arrangement of their collections inevitably dulls the interest they are supposed to arouse. Everything is shown; almost nothing is displayed…No effort is made to focus attention.”54 By that time, however, as we saw in chapter 3, much had already been done to answer his complaints; both of his suggested remedies—period decor and focused emphasis on masterpieces—had entered mainstream art museums. Such was the success of the Macy's-Met collaboration that from 1929 the museum hosted a series of exhibitions entitled The Architect and the Industrial Arts, in which major designers, including John Wellborn Root, Raymond Hood, Eliel Saarinen, Raymond Loewy, and William Lescaze, created seductive domestic room settings full of the latest in home furnishings (fig. 96).55 For a while art and design installations at museums and department stores became virtually indistinguishable. After a visit to the Met's 1934 applied arts exhibition, Lewis Mumford complained in the New Yorker that it “hardly differs seriously enough from that of a good department store to warrant the Metropolitan's special efforts.”56

Owing to such confusion, and to curatorial dislike of simulated environments more generally, designer installations enjoyed only a brief vogue in museums (they of course remain a staple of furniture showrooms). Bach's exhibitions were canceled during World War II, and the Met, like most art museums, never again invested seriously in contemporary design.

The exception to the rule was the Museum of Modern Art, which in the 1930s embraced modern design and set the standard for “showmanship” with respect to high art. A sparse hang in intimate rooms with white walls and focused light has become so ubiquitous that it is hard now to see the showmanship involved. But perhaps it can be best appreciated where least expected, in the 1934 Machine Art exhibition designed by architect and curator Philip Johnson (fig. 97). Johnson's simple but effective move in that installation was to cross Simonson's two forms of showmanship by displaying industrial products and applied arts not in a contextual setting, as at the Met and nearby department stores, but isolated like masterpieces of high art. Ignoring the function and working contexts of ball bearings, boiling flasks, and propellers and stressing instead formal qualities of material, surface, and volume through presentation, lighting, and photography, Johnson transformed utilitarian products of the machine age into seductive ready-made sculptures. One critic said the exhibition proved Johnson to be “our best showman and possibly the world's best.” The New York Times said it represented his “high-water mark to date as an exhibition maestro.”57

From its earliest days MoMA had expressed an interest in contemporary design, yet the design ethos under Barr and Johnson owed more to European modernism than to the everyday concerns dear to Dana or Bach. The Machine Art exhibition, for example, did feature products that could be had in local department stores, but the emphasis was placed on things that had little resonance with middle-class shoppers on Fifth Avenue. The museum bulletin claimed the exhibition served “as a practical guide to the buying public,” but how many households needed the ring of ball bearings that graced the catalog cover or the oversized spring voted the most beautiful object by a panel of celebrity judges? The most familiar photograph of the show highlighted objects that had little place in the home (fig. 97). According to ARTnews, “[T]he man in the street feels that these things are all very nice, but that the pure joys of functional beauty are for the cerebral aesthete.”58 Notably absent from the exhibition were those contemporary U.S. designers—Loewy, Bel Geddes, Walter Teague, Henry Dreyfuss—whose work had revolutionized product design in everything from trains to telephones.59 By 1934 their “streamlined” products could be seen everywhere—from the Met annual show to department stores and city streets—except at MoMA. Having saturated the market, those designers succeeded in realizing Henry Cole's dream of integrating quality design, mass production, and efficient distribution to a broad consumer public. But for the men at MoMA, streamlining's reliance on sensual effect and advertising to sell products and planned obsolescence to endlessly renew consumer desire had cheapened contemporary design and warped public taste. MoMA's mission was to counter the superficial allure of commercial design, and to that end it privileged the structural austerity of European modernism. Where native design had “sold out” by catering to popular tastes, European design retained its integrity, that is to say its distance from the mass market, through kinship with modern architecture and rejection of seductive ornament. Le Corbusier, in his book The Decorative Art of Today (1925), dismissed decoration as a form of disguise for poor quality. “Trash is always abundantly decorated,” he wrote; by contrast “the luxury object is well made, neat and clean, pure and healthy, and its bareness reveals the quality of its manufacture.”60 The latter appealed to sophisticated tastes, while “decorative objects flood the shelves of the Department Stores; they sell cheaply to shopgirls.” For Europeans—and by extension the men at MoMA—streamlining came to be seen as the hallmark of a vulgar, fad-driven society.61 Perhaps the issue of integrity and betrayal was sharpened by the fact that streamlining's leading advocate, Raymond Loewy, was a French èmigrè and contemporary of Le Corbusier who had struck it rich in America. In 1949, toward the end of his illustrious career, Loewy appeared on the cover of Time magazine surrounded by his products and a caption that read “He streamlines the sales curve,” a reference to his own definition of good design as “a beautiful sales curve, shooting upward.”

97. Installation view of the Machine Art exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, 1934. Photo: Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Art Resource, New York.

Nowhere was MoMA's rejection of mainstream taste and commercial culture more evident than in the exhibition Art in Our Time, organized to coincide with the 1939 New York World's Fair. As a counterpoint to the enormously popular, streamlined, corporate-sponsored pavilions designed by Loewy, Bel Geddes (fig. 43), and others, Art in Our Time limited its section on design to four single European chairs by Le Corbusier, Mies, Marcel Breuer, and Alvar Aalto (and a futuristic bathroom by Buckminster Fuller).62

To be sure, beginning in 1938, under the guidance of John McAndrew, Philip Johnson's successor in the design department, MoMA organized a series of traveling exhibitions of inexpensive useful objects, following the example of John Cotton Dana in Newark. (A price limit per object was first set at $5 and later rose to $100.) Subscribing institutions included colleges, department stores, and local art associations: “[T]he lenders, including retailers, wholesalers and manufacturers, received gratifying requests from all over the country and several wholesalers found enough attendant business in the provinces to establish new retail outlets in other sections of the country.”63 In 1940 MoMA hosted an exhibition entitled Organic Design in Home Furnishings with the aim of fostering collaboration between designers, merchants, and manufacturers. Department stores, led by Bloomingdale's, sponsored prizes in return for the right to sell the winning designs. Installations simulated domestic environments, in some cases down to picket fences and fake lawns and trees.64 The Useful Objects shows were canceled in 1948 but briefly reborn with a modified focus between 1950 and 1954 under McAndrew's successor, Edgar Kaufmann Jr., son of the Pittsburgh department store founder (who naturally viewed his emporium as a font of good taste for the consuming public). Kaufmann's Good Design shows, organized in conjunction with the Merchandise Mart in Chicago, also enjoyed success during their brief run. Extensive media advertising promoted the exhibitions; a television game show involving chosen products was even planned. Selected pieces were stocked by department stores with MoMA “Good Design” labels to boost sales.

The design exhibitions struck a chord with middle America, but their emphasis on “shoppers” and improving “the quality of many Christmas gifts,” as museum patron A. Conger Goodyear sarcastically put it, was out of step with the increasingly canonical direction of the museum.65 In 1953 MoMA officially became a collecting institution and abandoned direct involvement in the retail end of design. Thereafter the museum dedicated itself to acquiring objects of the past on the basis of their “quality and historical significance.” Those criteria come from the catalog to Arthur Drexler's 1959 exhibition Introduction to Twentieth-Century Design from the Collection of the Museum of Modern Art and were used to justify the exclusion of utilitarian objects—“not because such objects are intrinsically unworthy, but because too often their design is determined by commercial factors irrelevant, or even harmful, to aesthetic quality.”66

The Blockbuster Era

In museological terms, the 1950s may be viewed as a period of professional consolidation following the populist expansion and experimentation of previous decades. Budgets were under control, the art market flourished, and museums found themselves in the steady hands of curators and directors whose connoisseurial priorities aligned with the interests of their patrons and collectors. Commercial overlaps disappeared, audiences became more elite, and a solemn hush prevailed. But all that began to change in the 1960s and 1970s because of a resurgence of populism and mounting financial challenges. For reasons both ideological and economic, museums turned to marketing and high-profile programming to increase and diversify visitors and raise revenue. Progressive leaders of major urban institutions expanded outreach at the same time that the ranks of middle-class “culture consumers” (to borrow the resonant title of Alvin Toffler's 1964 book) multiplied. In 1963, as a Cold War demonstration of cooperation between “free world” allies (fig. 98), the Louvre sent Leonardo's Mona Lisa to the National Gallery in Washington, an event that drew some two million people. The gallery's director, John Walker, recoiled at the sight of “busloads of tourists” engaged in superficial “cultural sightseeing.” These were not the “truly devout” that, in his opinion, justified “the maintenance of public collections.”67 But they underlined the magnetic power of the masterpiece and revealed the potential size of the public for art. The modern “blockbuster” era had begun.

98. Mona Lisa crowds at the National Gallery, 1963. Photo courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., Gallery Archives.

The exhibitions organized by Thomas Hoving at the Met in the late 1960s are often referred to as the first real blockbusters, but it depends on how the term is defined. Certainly large-scale shows full of masterpieces and accompanied by extensive publicity were nothing new in the 1960s. If size, quality, foreign loans, and publicity are the blockbuster's essential criteria, then the Italian Renaissance exhibition held at London's Royal Academy in 1930, with its star pictures considered by some too fragile to travel and “crowds…so great that one couldn't possibly see the pictures,” would surely qualify.68 So, too, would the van Gogh show at MoMA in 1935. “By the time the exhibition opened in November,” recalled Russell Lynes, “the press coverage had already made it famous and nearly every suburban housewife knew about van Gogh's ear.”69 Reviews declared the show “superb,” “fraught with wonder,” “magnificent.” To the annoyance of local businesses, a banner advertising the show (among the first of its kind?) hung over the street in front of the museum. “Store windows on Fifth Avenue were filled with ladies' dresses in van Gogh colors, displayed in front of color reproductions of his paintings. His sunflowers bloomed on shower curtains, on scarves, on tablecloths and bathmats and ashtrays.” Queues stretched around the block. Trains marked “Van Gogh Special” brought people from as far away as nine hundred miles. Attendance in New York over a two-month period reached 123,339; a further 227,540 people saw the show in San Francisco. The show's success confirmed Philip Youtz's assertion a year earlier at the Madrid museum conference that temporary exhibitions were “agreed to be one of the methods best calculated to attract the general public.”70

Though a small admission fee was charged for the Van Gogh exhibition, money was not MoMA's motive for organizing it. For Barr what mattered was cultivating a broad public for high art. Similarly for Hoving, at least in his first blockbusters, including Harlem on My Mind, populism and publicity (for himself and the Met) came before profit. If making money has become a fundamental goal of the blockbuster as we know it today, we can trace the origins of the phenomenon to the moment in the late 1960s and early 1970s when rising financial pressures made generating revenue a chief impetus for exhibition planning.

By the 1960s, the income from loyal benefactors, endowments, and local subsidies was no longer sufficient to meet the rising costs of building maintenance, new programs, and staffing in many private museums.71 State-run museums were insulated from economic change, but those without substantial government subsidies (which includes most museums in the United States) were forced by budget shortfalls to seek new audiences and to entice visitors new and old to give and spend money. Through the 1950s, development offices, capital campaigns, marketing, and membership drives were virtually unheard of in art museums. Admission charges were rare. Gradually, however, recurring deficits forced museums to join universities and hospitals in charging for services, enlarging their circle of generous friends, and pursuing grants and donations. To increase attendance and justify new fees and solicitations, museums had to make themselves more appealing, which meant renovating or adding buildings and expanding programs, which in turn entailed additional staff and higher associated costs. The old art museum public wasn't big enough to pay the bills, and new audiences, surrounded by recreational alternatives, required new forms of stimulation to keep them coming back. At the same time grant-awarding agencies wanted tangible results for their investment in the form of healthy visitor numbers.72 Museums gradually became audience driven, and, as everyone knew, there was no more effective way to attract crowds than the welladvertised blockbuster exhibition.

Because they are dependent on heavy marketing and valuable masterpieces flown in from distant museums, blockbusters are expensive to mount, but their proven popularity has made them attractive to corporations willing to exchange financial support for advertising. To make a profit, museums then charged special admission and created new spending opportunities; and to keep the profits flowing, major exhibitions had to be planned to follow one another with regularity. In short, beginning in the 1970s, blockbusters became many museums' financial salvation. As Jay Gates, director of the Phillips Collection in Washington, observed in 1998 at the height of the blockbuster craze: “It is no longer a revelation to observe that, over the course of the last 30 years, art museums in America have come to be driven, if not dominated, by their major exhibition schedules. Virtually everything that is quantifiable about America's major museums follows the performance of their exhibitions…. Attendance, ticket sales, membership, shop revenues, activity in the cafè, the private use of the building for business or social purposes—all of these things climb or fall in connection with exhibitions.”73

Because it has always been heavily dependent on private funding, Boston's Museum of Fine Arts offers a particularly good example of creeping commercialism in the art museum. Though we think of it (and others like it) as a “public” institution, it was founded and for much of its history financed by local benefactors. The MFA received no public subsidies until 1966, when the city stepped in to subsidize visits by local schoolchildren.74 It remains the least subsidized major urban art museum in the United States. Over the years costs regularly exceeded income, but the problem became acute in the 1960s, and a new approach was needed. In 1966 the museum imposed a general admission fee for the first time in fifty years. Further deficits ensued, leading to raised admission fees and internal cutbacks. A Centennial Fund drive, the first of its kind in the museum's history, was launched to pay for a building that would offer new “creature comforts” in the form of an auditorium, added exhibition space, and a better restaurant.75 The board of trustees was enlarged “to attain a larger number of trustees who would give substantial sums themselves or assume close personal responsibility for…fundraising in relation to a permanent Development Department.”76 As important as behind-the-scenes efforts were, then-director Perry Rathbone acknowledged in the early 1970s that it would take a host of new public initiatives—“exhibitions of international scope, events of record-making popularity, breathtaking acquisitions, lavish publications, programs involving visiting scholars, seminars, and films”—to significantly boost attendance and revenue. The measures were sufficiently novel to warrant a public explanation: “While we believe that such programming is not outside the province of museums, it is no secret that the motivation behind this effort has been, perhaps, less to deepen the experience of our visitors than to broaden the appeal of the museum and thus to increase its income.”77 Half a century earlier Rathbone's recipe might have been justified as “showmanship” aimed at broadening access, but now the goal was raising money. In fiscal year 1971 popular exhibitions of the work of Andrew Wyeth and Cèzanne produced record attendance and merchandise sales, but a year later, Rathbone's last as director, with no blockbusters scheduled, the red ink returned. In his seventeen years at the museum, Rathbone witnessed membership grow from two thousand to fifteen thousand and shop revenues increase tenfold from $30,000 to $350,000; annual and corporate appeals had been introduced. Yet owing to inflationary pressures the museum was no closer to financial stability.

Recurring deficits in the mid-1970s forced the MFA to reduce hours and increase admission fees, triggering a significant drop in attendance and revenue. In 1975–76 a new president of trustees, Howard Johnson, was brought in to revitalize the museum.78 Johnson, a former president of MIT and dean of its business school, initiated another capital campaign, hired a money manager and other managerial staff, and began planning a major physical expansion that would result in I.M. Pei's West Wing (fig. 48). All the while, he realized above all that “the program must also become more attractive to our potential viewers.”79 Confronted with escalating admission charges and membership fees, visitors expected a greater return on their investment. Though averse to the language and practices of for-profit business, the MFA and other museums had no choice but to welcome the marketers, managers, and merchandise and to start treating their visitors as customers.

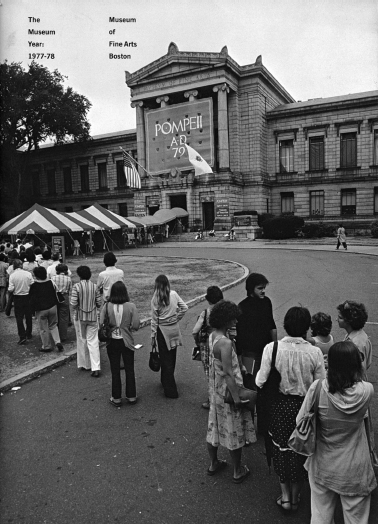

In 1977–78 a model for the new Pei extension went on display amid a string of popular exhibitions (in the old building) that included Pompeii AD 79, Thracian Gold, Monet Unveiled, Peter Rabbit, Art in Bloom (paintings paired with elaborate flower arrangements), Winslow Homer, and Hiroshige, a list that reveals a marketer's grasp of public taste. Almost half of the 892,000 visitors to the MFA that year lined up to see the Pompeii exhibit (fig. 99) and to buy related posters, T-shirts, mugs, and buttons that read “I survived Pompeii.” It was among the first shows at the MFA to offer an audio guide and to receive corporate sponsorship (from Xerox). Retail sales doubled, membership rose, and the restaurant enjoyed a profit for the first time in years. A visiting celebrity—Peter Falk, star of the Columbo television show—graced the back cover of the annual report, shopping bag in hand. A winning formula had been established, and with the opening of the Pei wing in 1981, providing space for traveling blockbusters, a much-expanded shop, and new restaurants, attendance climbed above one million and the museum enjoyed its first budget surplus ($126,000) in a decade. Further good years followed, culminating in the annus mirabilis of 1985, when a Renoir retrospective set a record for exhibition attendance and boosted the museum's surplus to $2.5 million. Thanks to unprecedented marketing on television and in the print media (paid for by IBM), a market survey commissioned by the museum discovered that 83,000 people came to the MFA for the first time to see the Renoir exhibit and that 3,654 of them became new members. The annual report stated: “The highly developed ancillary services of the Museum helped make ‘Renoir’ much more than a simple box-office success and enabled the Museum to restore to the endowment all of the operating deficits taken from it during the seventies.”80

99. Front cover of Annual Report, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1978.

A downturn in corporate giving in the late 1980s compounded by significant cutbacks in federal aid to the arts during the Reagan administration made it all the more imperative that the MFA follow up the success of Renoir with other popular exhibitions. It had become clearer than ever, at the MFA and elsewhere, that blockbusters made the museum world go round. In 1990, the museum hosted the immensely popular Monet in the 90s: The Series Paintings, which helped to generate another surplus of $2.4 million. “If we could have a Monet exhibition every other year,” the president of the trustees wrote, the museum “would have few financial concerns…. In the years when these unusual events are not part of the program, the Museum is finding it increasingly difficult to make ends meet.”81 Indeed, the following year further deficits were again projected and staff laid off for the first time in the museum's history. “As we have now learned,” he admitted, blockbusters offered a quick fix but they “cannot sustain the future.”82

From the 1990s a more complex and sophisticated response to financial challenges emerged at the MFA and other museums. Under a new director, Malcolm Rogers, blockbusters became more frequent to avoid down years between major events. The fiscal year 1998–99 witnessed three major impressionist blockbusters in a row: Monet in the 20th Century (569,000 visitors), Mary Cassatt: Modern Woman (230,750), and John Singer Sargent (320,000). In all there were seventeen shows during the year contributing to a total attendance of 1.7 million, a record-high 103,000 memberships, and a reported surplus of $1.9 million. The museum found new ways of exploiting the perennial appeal of impressionism, plumbing its own permanent collection for the exhibition Impressions of Light: The French Landscape from Corot to Monet (2002), which was marketed as a blockbuster with the usual ticketed entry, catalogs, and banners. Beyond impressionism, programming ventured into new areas of popular interest with exhibitions on fashion, jeweled tiaras, celebrity photographs, rock guitars, racing cars, and the clay animation characters Wallace and Gromit.

In addition to exhibitions, Rogers created new departments of marketing and development and visitor services (“whose mandate is to introduce a culture of visitor awareness to the Museum with the goal of exceeding visitor expectations”);83 invited “young people” to attend Friday “singles evenings”; hosted a dog show, business receptions, and corporate-sponsored events; entered lucrative partnerships with the Nagoya Museum in Japan and a casino in Las Vegas; rearranged the permanent collection to better promote the MFA's famous impressionist paintings; introduced tiered levels of membership; raised member fees and admission charges (among the highest in the United States); expanded ancillary entertainment and culinary offerings; transformed the definition of the museum shop; and cut back on educational services to area colleges and universities that offered prestige but little profit. Rogers was heavily criticized in the art press and national media. “Show Me the Monet,” was the title of the Newsweek article announcing the MFA's deal with the Bellagio casino resort in Las Vegas, and reporters had little difficulty securing a negative comment on virtually any of his initiatives from peers in the art establishment.84 Those who criticized him, however, offered no constructive advice on how else to pay the bills at an institution that receives less than a quarter of I percent of its annual operating budget from state and federal sources.

Museum Shops

From the late nineteenth century through the 1960s, museum shops were often no more than a desk or corner in the lobby selling a few postcards and scholarly publications (fig. 100). Such materials were educational and offered as a public service. The subject of shops merited only a paragraph in Laurence Coleman's authoritative 1950 treatise on museums, and he was clear about their purpose: “Most small museums do their selling at the information desk, but some large museums have the sales job differentiated to the point of featuring a separate little bookshop…A few badly run museums make the mistake of offering mere souvenirs and other unsuitable stuff; but, properly conducted, the business of selling is useful.”85 One wonders what Coleman would have made of retail operations at today's museums, which frequently extend beyond a large gift shop to include specialized blockbuster shops (fig. 101), satellite outlets in malls and airports, and online/catalog shopping services. The new commercialism is perhaps most conspicuous at shops that accompany blockbuster exhibitions, not infrequently positioned at the exit to the show. At the MFA gift shop accompanying Monet in the 20th Century (1998), for example, visitors were tempted by the following orgy of Monet products: scholarly catalogs and books, videos, posters, framed reproductions, T-shirts and sweatshirts, postcards and pens, Monet watercolor and paint sets, chocolate paint palettes, kaleidoscopes, toys, cosmetic bags, coin purses, desk blotters, napkin holders, address books, personal organizers, water lily boxes, photo frames, stationery sets, note cubes and cards, wrapping paper, pillows, aprons, umbrellas, tote bags, night lights, magnets, calendars, “Monet's Garden Latte Cup and Saucers,” tray sets, trivets, soup bowls, cups, pasta dishes, plates, salt and pepper shakers, suncatchers, bottle stoppers, water bottle and cup sets, candle holders, soap, and Christmas tree ornaments. Set above the rest in terms of price was “Claude Monet's Museum Collection,” a line of domestic wares labeled “antique reproduction porcelain pieces…patterned after Claude Monet's own beautiful, white and yellow collection which he often filled with fresh fruit or flowers from his garden.” During a two-month stretch the museum sold fifty thousand postcards, thirty-four thousand catalogs, and ten thousand posters, not to mention plenty of what Coleman would surely have labeled “unsuitable stuff.”86 The MFA proved what retailers know to be true: “[A]nything Monet sells—anything.”87

100. Walker Art Center Lobby Book Corner, ca. 1942. Photo: Rolphe Dauphin. Photo courtesy of the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis.

101. Mary Cassatt exhibition shop, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1999.

Under U.S. law, museums avoid tax liability if what is sold at their shops is related to their educational mission. But the connection can be tenuous at times. Take, for example, the following label found on a box of Christmas crackers on sale at the MFA: “Our festive crackers are decorated with designs from William Morris patterns housed in the Museum's collection. The breathtaking design work of Morris & Co., catalyst of the Arts and Crafts movement, created some of the world's finest wallpapers and tapestries…. Morris' credo was ‘Have nothing in your house that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful.’” Flimsy rationales of this sort (which, moreover, represent a travesty of Morris's beliefs) breed cynicism and disparaging comparisons to the shopping mall, but for many museums today commerce is essential. According to Malcolm Rogers, it is “one of the pillars of the success of the museum.”88 In the hope of increasing profitability, in 2002 the MFA became one of the first American museums to turn its retail division into a for-profit company. For its managers, if not also MFA staff, there is no shame in comparisons to a mall. “Museums are the new malls,” said a buyer for the new store. “You can eat here, hang out, go to a movie or shop.”89 The atrium of Pei's West Wing (fig. 48), surrounded by potted trees, reflective surfaces, a cafè, movie posters at the theater box office, and a busy shop, makes analogies to a mall seem entirely appropriate. But does it matter if museums and malls overlap? The public clearly enjoys shopping in the museum; for many the shop has become an integral part of the visit.90 With the rise of self-contained and attractive shopping precincts (sometimes occupying historic sites such as London's Covent Garden or Boston's Faneuil Hall), shopping has joined museum-going as a leading leisure activity, engine of urban renewal, and reason for travel. According to Jeffrey Inala, co-editor with architect Rem Koolhas of the Harvard Design School Guide to Shopping (2001): “We have reached a moment when culture and retailing can no longer be separated.”91 “Our culture is a commodity culture,” observes John Fiske, “and it is fruitless to argue against it on the basis that culture and profit are mutually exclusive terms.”92 Koolhas himself is equally at home designing museums and upscale boutiques, notably his Prada store in New York (2001), described by the New York Times as a “museum show on indefinite display.”93

Recurrent warnings (from the elite on the right and left) that commerce will erode the public's regard for museums have yet to be substantiated.94 Commercialism has penetrated every facet of life in the United States, and it will slowly do the same everywhere. The challenge for museums is to be able to take advantage of commercial opportunities without sacrificing their rhetorical withdrawal from the everyday world. No one knows, or can agree on, where the line should be drawn. Leaving aside the tchotchkes that have no real relevance to the museum experience, the role of reproductions is itself a source of contention. Museums work hard to defuse the tension between the unique status of their masterpieces and their reproduction by defending the latter as a form of educational outreach. Note in the following statement from the Met store Web site how the museum blurs distinctions between original and reproduction, disinterested scholarship and commerce, in an attempt to sell shopping as central to its mission:

Visitors to The Met Store often ask how our products are selected and produced. Every product created by the Museum is the result of careful research and expert execution by the Metropolitan's staff of art historians, designers, and master craftspeople, who ensure that each reproduction bears the closest possible fidelity to the original. The Metropolitan's reproduction and publication programs are a source of pride to the Museum, not only because they are executed with a focus on quality and attention to art-historical scholarship, but also because publishing and reproducing our collection is part of the original mission of the Museum, and has been a tradition here for over a century.95

Proximity to the original and a pedagogic purpose are what elevate the shop's contents—and the shopper—above the level of kitsch. Reproduction enhances the stature of the original while making it available to everyone, as Andreas Huyssen has noted: “The original artwork has become a device to sell its multiply-reproduced derivatives; reproductability turned into a ploy to auraticize the original after the decay of aura.”96 Referring to the role of reproduction in the tourist's worldview, Dean MacCannell has observed: “It is…mechanical reproduction…that is most responsible for setting the tourist in motion on his journey to find the true object.”97 Discovery of that object prompts the traveler to secure his or her own authentic (“I was there”) reproduction in the form of a photograph, postcard, or other memento. For many, by extension, consumption of the reproduction frames, and is integral to, the experience of the “true object” in museums. Those who look down on museum shops and shoppers are the same people who denigrate mass tourism and the gaping crowds before the Mona Lisa. Art world insiders, who are invariably also citizens of the world, claim their own authenticity by distancing themselves from the tour groups and the Monet fridge magnets.

Though I have focused heavily on the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, it is hardly alone. Rising costs, shrinking government subsidies, and an uncertain economy have compelled museums everywhere, big and small, public and private, to behave more like businesses, expand their programs and buildings, and mount crowd-pleasing exhibitions. A small sampling of museums in the United States around the year 2000 reveals activities that would have been unthinkable a generation earlier. At the Brooklyn Museum visitors were encouraged to “adopt a masterpiece” and join in karaoke evenings between visits to an exhibition of hip-hop culture (Hip-Hop Nation: Roots, Rhymes, and Rage, 2000) and a self-promoting exhibition of the Saatchi collection (Sensation, 1999).98 A sparkling new entrance by James Polshek drew further attention to the museum. San Francisco's Museum of Modern Art organized an exhibition of athletic sneakers (Design Afoot: Athletic Shoes, 1995–2000), while the Houston Museum of Fine Arts hosted a show of Star Wars memorabilia (Star Wars: The Magic of Myth, 2001). Visitors to the Monet and Cèzanne blockbuster shops at Brooklyn and Philadelphia found everything from soup mixes and olive oil to Rodin-shaped pasta and autographed Cèzanne baseballs for sale.99 The Philadelphia Museum went one step further by packaging the Cèzanne show and its products for a home shopping television network. Thanks to admission fees and shop sales connected to the exhibition Van Gogh: Face to Face, the Detroit Institute of Arts saw its miscellaneous income in 2000 rise nearly tenfold over previous years to $9.6 million.100 Even the Met, despite Montebello's outspoken distaste for commerce and entertainment, boasts a solid record of corporate and retail involvement. “The Business behind Art Knows the Art of Good Business,” announced a Met brochure hoping to attract corporate sponsors in the mid-1980s.101 In 2001 the museum operated thirty-nine stores worldwide, producing over $87 million in revenue.102

No museum has gone further to emulate a business model than the Guggenheim under Thomas Krens. With degrees in fine art and financial management, Krens is the venture capitalist of the museum world, leveraging the Guggenheim collection and exporting the Guggenheim brand to new “branch” museums (franchises?) around the world. Since the 1990s he has angered the art world establishment by hosting exhibitions of motorcycles, Armani fashion, and the paintings of Norman Rockwell and doing business with a Las Vegas casino (fig. 94).103 While other directors quietly oversee the expansion of shops and restaurants, Krens openly embraces business practices and discourse. His by-now famous formula for the successful museum embodies values and language that his mainstream colleagues abhor: “Great collections, great architecture, a great special exhibition, a second exhibition, two shopping opportunities, two eating opportunities, a high-tech interface via the Internet, and economies of scale via a global network.”104 Even more commercial are the terms the Guggenheim's director of corporate relations used to defend its policies: “We are in the entertainment business, and competing against other forms of entertainment out there. We have a Guggenheim brand that has certain equities and properties.”105 Traditional museum people have always loathed Wright's building (as a museum), and its transformation into a seeming showcase for motorcycles and haute couture has only hardened attitudes. The press has reported Krens's triumphs and travails with great interest. Retrenchments at the museum following a downturn in the post-9/11 world economy prompted the following from Michael Kimmelman: “You could almost hear the door shut on an era. The age of the go-go Guggenheim was over…Having mimicked the dot.com businesses of the era, the hype about global networking, cutting-edge growth and a new economy, Mr. Krens's dream, like the bubble of the dot.coms, burst…. Mr. Krens was right in one sense. Arts institutions are not really different from other businesses, at least not when they act like them. They are just as vulnerable.”106 The Guggenheim empire may decline and fall; even the successful venture in Bilbao may wither over time, but the hard reality that museums are part of the entertainment industry and will need to innovate to survive financially cannot be wished away. As MoMA director Glenn Lowry has acknowledged: “No museum, except maybe the Getty, has an endowment big enough to be free of the marketplace, so all other museums have to retail products, solicit corporations, franchise themselves, seek members.”107

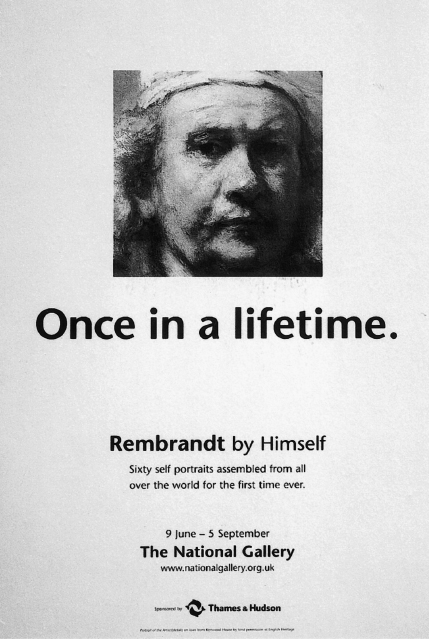

102. Advertisement for the Rembrandt's Self-Portraits exhibition, National Gallery, London, 1999.

The economic challenges of the 1970s and 1980s affected small private museums as much as large civic ones. In Boston, inflation and pressing conservation needs awoke the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum after decades of genteel slumber. Gardner's original endowment no longer covered expenses, the cafè ran at a loss, the modest shop barely broke even, and the membership program cost more than it earned. The centuryold building badly needed climate control. An aging board of trustees had neither the expertise nor the personal resources to solve the problem. In 1987 a new director, Anne Hawley, modernized the museum from top to bottom, reforming and enlarging the board of trustees and initiating financial planning, a capital campaign, development and public relations departments, and dynamic new programs. Only the museum's installation, set in stone by the terms of Gardner's will, remained the same.108

Recent cutbacks in government funding have left European museums with little choice but to follow suit. Throughout Europe governments are pressuring museums to earn more of their own keep through increased retail, catering, and corporate sponsorship.109 The most august of state-run museums have begun to hype blockbusters (fig. 102) and open their doors to commerce. Donor plaques and “naming opportunities” are as commonplace in Europe as they are in the United States. Beneath I.M. Pei's Pyramid at the Louvre, visitors may browse and eat at an American-style shopping mall and food court.110 Corporate funds paid for the Louvre's new English galleries and Mona Lisa room and for the restoration of the Apollo Gallery. In 2007, the Louvre sold its name for $520 million to a new museum rising in Abu Dhabi.111 Money from a chain of grocery stores and a French couturier paid for the Sainsbury Wing and the Yves Saint Laurent Room at London's National Gallery. The Spanish government hoped 40 percent of the Prado's budget would be covered by corporate donations by 2008.112 Museums in Italy are being privatized.113 And so on. Where once Europeans scoffed at the commercialism of U.S. museums, now they are looking across the Atlantic for ideas and cash, in some cases entering into joint commercial ventures and appealing directly to wealthy North American donors.114

Weighing the Costs of Commercialism