The country of Peru borders Ecuador, Colombia, Brazil, Bolivia, and Chile. Its terrain is diverse, including “western arid coastal plains, central rugged Andean mountains, and eastern lowlands with tropical forests that are part of the Amazon basin” (U.S. Department of State 2009a). As is the case in many postcolonial states, the legacy of imperialism has been felt in a number of different ways. Peru has experienced a tumultuous political history. After Peru fought for independence from Spain, which it received in 1821, the regime changed hands twenty-four times between 1821 and 1845 (“Military Reform” 1992). Political instability has remained a challenge. Ideological differences play a significant part in the rivalries that have formed and their resulting conflicts.

Strife has also been layered in identity. Amid a diverse topography, not surprisingly, lives a diverse population of people largely defined by race. Although the majority of the population is indigenous, such groups exhibit disproportionately higher rates of extreme poverty than those of European descent or of mixed heritage (i.e., mestizo) (McClintock 1989; Strong 1992). The colonial legacy, involving political instability and differing racial classes with preferential treatment, creates the backdrop in which multiple rivalries emerged in the post–World War II era. The case provides an in-depth look at both episodic and enduring rivalries, all of which have resulted in similar frustrations. Despite the shared set of grievances, rivalries that occurred at the same time never coalesced and even sometimes fought against one another. Infighting among rivals in Peru helps in part to explain the conflict trajectories and tactical decisions that are examined here.

A state’s terrain can provide refuge for groups engaged in armed struggle against their government. This is certainly the case in Peru. The more remote mountainous and jungle regions of the country are where the bulk of armed struggle has occurred. All conflicts examined in this chapter have emerged from or otherwise benefited from the country’s terrain. Guerrilla warfare is the primary tactical approach employed by most of the conflict actors in Peru as a result. It is not the only tactic employed, however. Why that is the case has to do with cultural cleavages that exist in Peru, as well as the ideological and organizational structure of the key rebel faction, Sendero Luminoso.

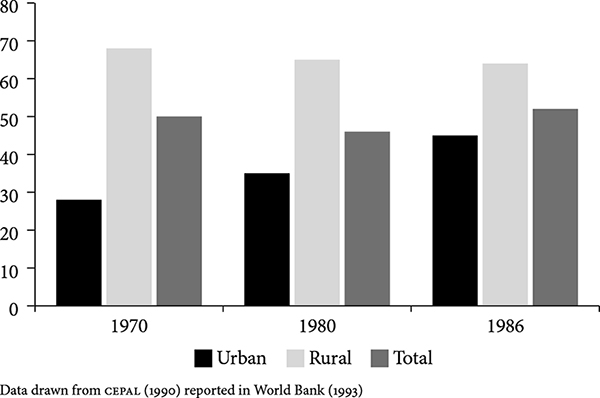

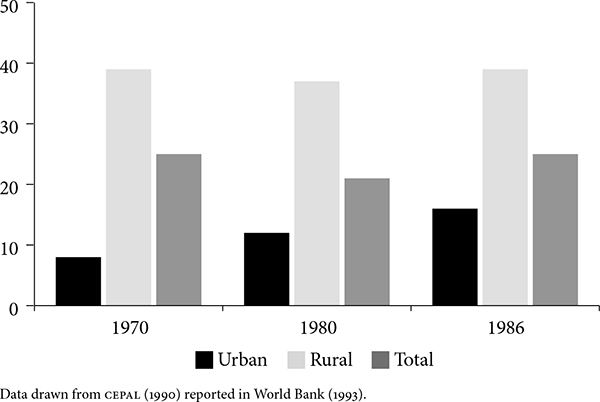

The armed struggle in Peru is also deeply a function of the country’s cultural and historical experience. It has the most unequal land tenure system in Latin America (McClintock 1989). Further, poverty rates have been historically high. Some Peruvian regimes have made headway into this problem. In 2005, the national poverty rate was 55.6 percent. By 2013, it had dropped to 25.8 percent (“World Development Indicators” 1960–2014). As with land, the percentage of those at or below poverty is unequally dispersed geographically. Among the urban population, in 2012, the poverty rate was 16.6 percent, whereas among the rural population, the rate was an astounding 53.0 percent (“World Development Indicators” 1960–2014). This snapshot of poverty represents a clear gap between the progress of those in the coastal, more urban areas and those in the Sierras. Throughout Peru’s history, as the country progressed it did so unevenly. This is illustrated in Figures 7.2 and 7.3. When the country experienced economic hardship, those in the lower socioeconomic strata felt the most drastic impact.

This gap emerged early in Peru’s history but became worse in the 1950s and 1960s as agricultural production stagnated in the midst of continued population growth and import substitution industrialization policies took their toll (Kay 1983). This coincided with the shift of the dominant political party, American Popular Revolutionary Alliance (APRA), toward the right, which sparked the first set of conflicts and elite-level rivalries analyzed below. As the figures indicate, Peruvians in the rural areas of the country have been significantly more likely to live at or below the poverty line over time. Nearly 40 percent were in situations of extreme poverty.1 Poverty had increased for Peruvian urban populations over the time period examined here, but remained significantly lower than rural percentages. Further, by the early 1960s, 0.1 percent of the Peruvian population controlled 60 percent of the cultivated land (UCDP/PRIO 2014).

FIGURE 7.2 Peruvian Urban and Rural Poverty Rates, 1970, 1980, 1986

FIGURE 7.3 Peruvian Urban and Rural Extreme Poverty Rates, 1970, 1980, 1986

As was the case in many postcolonial, struggling countries, the poor migrated in search of work, which in part explains the increasing poverty levels in the urban centers illustrated in Figure 7.2. Migration to coastal cities brought with it the establishment of shantytowns. Governmental response to pervasive poverty and discontent in the Sierras involved efforts by the Belaunde government of the 1960s to provide modest agrarian reform and development projects in the high jungle (Crabtree 2002). These were ineffective and as a result failed to appease frustrated migrant urban youths or alienated peasants in the high country. Further, one of the initiatives to address underlying grievances had an even more problematic impact. In an effort to alleviate underdevelopment in the Sierras, the Peruvian government expanded educational opportunities for the poverty stricken. As a result, more universities were opened in administrative departments such as Ayacucho and Huancavelica.2 Graduates of these schools, however, were unable to find employment as economies in these regions continued to be depressed and inequality remained, leading to further frustrations and political mobilization.

The Peruvian government made serious attempts to address this underlying inequality following the military coup of 1968 that deposed Belaunde. Under the leadership of General Velasco, Peru nationalized much of its industry, redistributed land, embarked on structural reforms, and more generally undermined the economic base of power of the old ruling classes (Champion 2001). These efforts, however, led to increased national debt and spiraling inflation. Attempts at austerity in the late 1970s gave way to renewed mobilization in the form of strikes and protest. Economic hardship continued through the 1980s, coinciding with the reintroduction of democratic leadership beginning in 1980. Inequality and inflation serve as the backdrop for a second set of rivalries that emerged at this time.

Inequality in Peru is complex. According to Strong, a tension exists between Western and Indian culture: “The idea that the vast majority of the population— Indian peasants, small merchants, miners, industrial workers, and wandering street vendors—is discriminated against racially is not even entertained. Yet their poverty, which stems from a history of economic stifling and exploitation by the whites, is dismissed as inevitable and their plight next to hopeless on the grounds of their race” (Strong 1992, 51).

Layers of identity in Peru involve where one lives, one’s ancestry, and one’s language, but in particular the indigenous Spanish identity is powerful, with significant implications for one’s status in society. Ideology may be the mobilizing identity in the country, at least among the rivalries examined here, but the role of these other identities cannot be ignored. The animosities that exist between these varying identities may help to explain how ideological rivalries that appear ripe for guerrilla activity turn toward terrorizing civilian populations, the very people the leftist ideology sought to save.

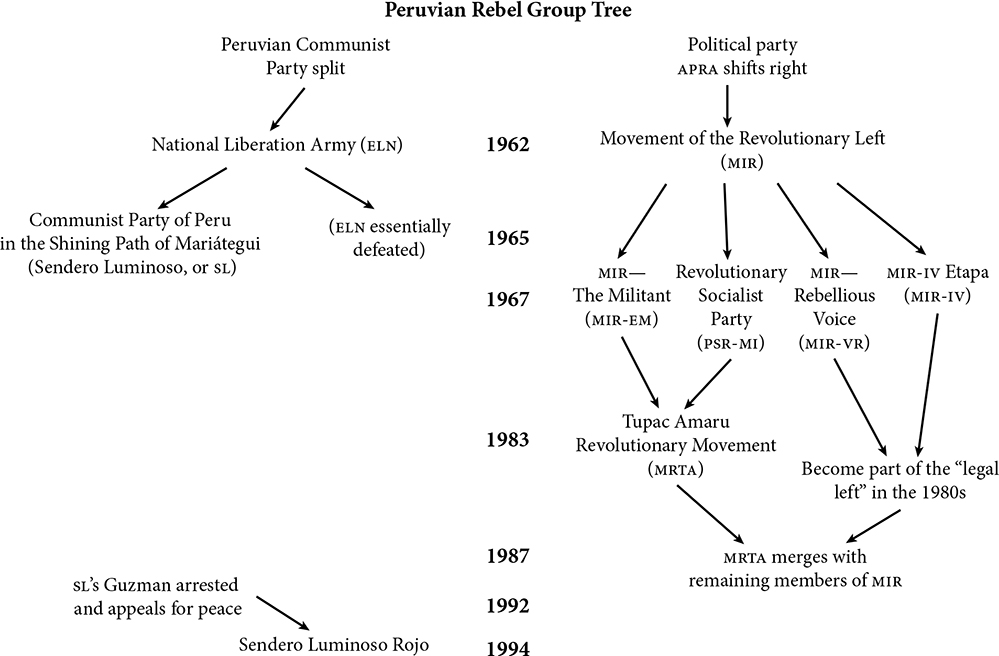

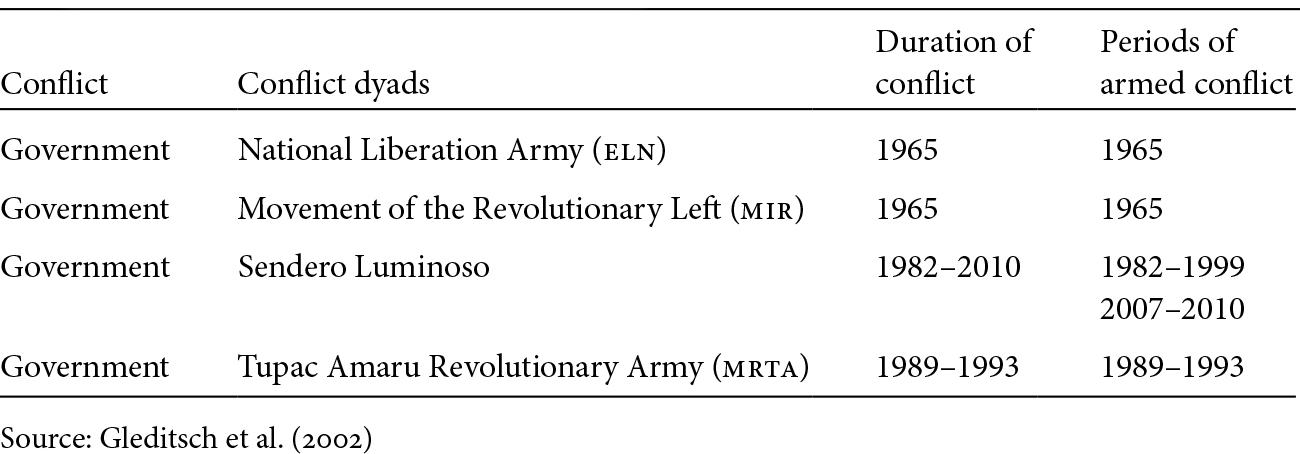

Peru has experienced four different armed conflicts with a short bout of violence in 1965 involving two factions and two more sustained intrastate conflicts that began in 1982 (Gleditsch et al. 2002). Each was leftist in nature and emerged over the same set of grievances. As a result, their histories are intertwined even when groups remained distinct from one another. Figure 7.4 illustrates how and when these groups emerged. The most well-known rebel faction to the Peruvian government is Sendero Luminoso, originally named Communist Party of Peru in the Shining Path of Mariátegui (i.e., “Shining Path”). Sendero’s predecessor, however, was the National Liberation Army (ELN), which split from the Peruvian Communist Party in the early 1960s (Béjar 1969). In a similar fashion, the Movement of the Revolutionary Left (MIR) emerged in response to the decision by the American Popular Revolutionary Alliance (APRA) to become more moderate in order to gain political power. In 1962, APRA decidedly embraced an anti-Communist and anti-Castro position. Further, APRA supported cooperation with the United States (Keesing’s World, August 1962). Both the ELN and MIR mobilized in 1962 in response to the shifting political landscape and engaged in armed struggle beginning in 1965 (UCDP). MIR began its attacks from Cuzco and Junin, while the ELN emerged in Ayacucho. Despite the small size of these groups (discussed further below), each was able to survive for several months in the face of significant repression on the part of the government because of the terrain in which they operated. However, both were readily defeated by the Peruvian military, which appeared to bring these episodic conflicts to an end.

TABLE 7.1 Timeline of Key Events in Peruvian Conflicts, 1945–1997

Date | Event |

1945 | Civilian government of Jose Luis Bustamante elected |

1948 | General Manuel Odria overthrew Bustamante |

1956 | Manuel Prado y Ugarteche elected with the backing of the American Popular Revolutionary Alliance (APRA) |

1962 | Military coup. APRA moved from leftist to moderate. |

1963 | Constitutional government formed by the Popular Action (AP) party. Fernando Belaunde Terry became president. |

1965 | National Liberation Army (ELN) and Movement of the Revolutionary Left (MIR) began their insurgencies. Neither survived longer than three months. |

October 1968 | Bloodless coup led by Juan Velasco Alvarado. Congress dissolved. Inca Plan in place socialized economy. |

August 1975 | Velasco overthrown by Francisco Morales Bermudez Cerruti |

September 1975 | Oscar Vargas Prieto replaced Morales Bermudez |

January 1976 | Jorge Fernandez Maldonado replaced Vargas |

July 1976 | Fernandez replaced by Guillermo Arbulu Galliani. State of emergency declared following unrest of austerity. |

January 1978 | Arbulu retired. Molina Pallochia replaced him. Constitutional assembly elected, paving the way for democracy. Belaunde Terry and his AP party won. |

1982 | Sendero Luminoso began operations in Ayacucho department |

1984 | Tupac Amaru Revolutionary Army (MRTA) began its armed struggle. Sendero’s conflict intensified. |

1985 | Economic crises |

April 14, 1985 | APRA’s Alan García Pérez won election. Economic crises continued. Government prematurely declared victory over Sendero. MRTA briefly suspended its campaign. |

1986 | MRTA renewed its campaign |

1989 | Victor Polay of MRTA captured, later to escape |

July 28, 1990 | Alberto Fujimori took office as president |

April 1991 | Sendero launched new wave of attacks |

June 1991 | Congress granted emergency powers to Fujimori |

April 5, 1992 | Fujimori dissolved Congress in self-coup September 12, 1992 Abimael Guzman of Sendero captured |

1993 | Polay arrested |

December 17, 1996 | MRTA took Japanese embassy in Lima |

April 22, 1997 | MRTA embassy siege ended |

Source: CQ Press (2009a). | |

FIGURE 7.4 Peruvian Rebel Group Tree

TABLE 7.2 Conflicts in Peru, 1965–2010

The ELN, however, had splintered when its leadership decided to take up arms in 1965. Abimael Guzman, along with a contingent of followers, broke away from the ELN, choosing instead to pursue a longer term, revolutionary strategy. Guzman became the well-known leader of Sendero Luminoso.

The MIR also splintered following the death of its leader during the 1965 outbreak of violence. Four separate groups emerged as indicated in Figure 7.4. The MIR, MIR—the Militant (MIR-EM), and the Revolutionary Socialist Party (PSR-MI) found more common ground in the 1980s, emerging as the Tupac Amaru Revolutionary Movement (MRTA) in 1983. A new armed struggle, and the fourth faction emerged. MIR was essentially defeated as an armed opponent in 1965. Those that continued to operate did so politically. In 1986, however, the remnants of the MIR merged once again with MRTA. Although both Sendero and MRTA were active during the same time period, and even shared the same leftist orientation vis-à-vis the government, they never coalesced. In fact, Sendero often targeted MRTA members and other leftist opponents during its campaign.

Both Sendero Luminoso and MRTA were engaged in more sustained conflicts with the state than the previous ELN and MIR factions. Although Sendero began mobilization in the aftermath of the 1965 armed conflict, it did not become an active rivalry until 1980, when it launched its guerrilla war against the government of Peru out of the Ayacucho region (Peruvian Times 1990). It is under the dire economic conditions of the Sierras, which were brought about by the inflationary policies of the administration described earlier, that this armed struggle took place. Although poverty levels and inequality in the Peruvian system have changed over time (in fact, recently national poverty levels have declined), the divide between the urban centers and the more rural territory of the country has remained. This division is central to the longest-lasting conflict involving Sendero.

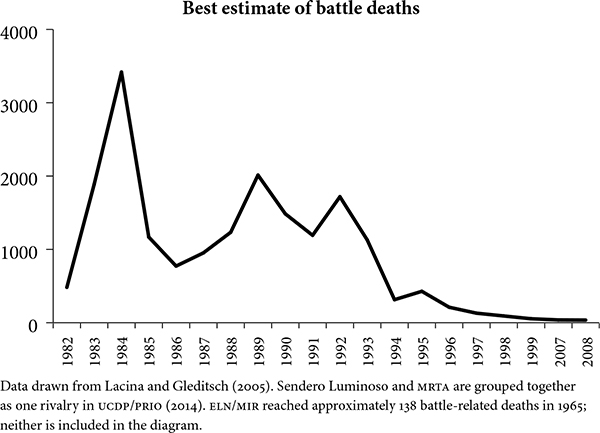

Sendero Luminoso was organized first at the University of Huamanga in Ayacucho, a region that is isolated from the urban centers of Peru. As a result, the initial mobilization went largely unnoticed or was ignored (de Witt and Gianotten 1994). Later in the Sendero conflict, the group shifted toward northern Peru, focusing on the Huallaga Valley, where they were able to benefit economically from their role in the drug trade (discussed further below). The group built momentum during the early 1980s as the government failed to take it seriously. Conflict intensified in 1983 and 1984 as the Peruvian military turned its attention to the countryside in pursuit of Sendero rebels. By 1985 the government declared victory, albeit prematurely. Although numbers of casualties decreased during 1986 and 1987, Sendero presence continued to be felt among the indigenous population. Further, group activity spread to include attacks on Lima and areas bordering both Ecuador and Bolivia, as well as establishing a foothold in the Huallaga Valley, the center of coca production (UCDP). After this brief lull, Sendero renewed armed struggle in the late 1980s and early 1990s when the group’s power peaked (Center for Defense Information 2003). In 1992, however, Guzman was captured. As a movement, Sendero continued beyond that time, maintained significant operational capacity (Palmer 1994), and even spawned the splinter group Sendero Luminoso Rojo. Its impact was significantly diminished, however. The group makes use of the dense jungle terrain in the Vraem region of eastern Peru, where the government estimates that 80 members remain in operation, though the rebels claim a force of 350 (Martel 2015).

MRTA officially began its armed struggle against the Peruvian government in 1984 (Center for Defense Information 2003). Unlike its predecessors, MRTA did not embrace rural guerrilla-based warfare. Its campaign began in Lima, located on the coastal flatlands. However, even in this case, the mountains provided sanctuary for the rebels. In fact, Victor Polay, the leader of MRTA, was first captured in 1989 in the Andean city of Huancayo along with forty-seven other group members (Los Angeles Times 1989). Prior to that, however, in 1985, MRTA had suspended its campaign following the election of APRA’S Alan García, a childhood friend of Polay (Baer 2003). When it failed to experience the anticipated land reform, at least to the extent desired, MRTA took up arms again in 1986. The group was at its strongest, coinciding with the heyday of Sendero, in the late 1980s. Counterterrorism efforts of the Alberto Fujimori administration greatly diminished the power of MRTA by the end of 1993 (Palmer 1994), although not entirely. MRTA staged its last and most notable assault in 1996, when a group of MRTA members (numbering fourteen to twenty-five, depending on the source) stormed the Japanese Embassy in Lima and took approximately five hundred people hostage. The siege continued for 126 days, after which Fujimori, having refused any of the hostage takers’ demands, used commandos to retake the embassy (CQ Press 2009a). All MRTA members were killed along with one hostage (Center for Defense Information 2003). The group continues to exist, although its armed approach appears to have ended. Its focus has changed in light of the 1996 embassy attack. Rather than engage in armed insurrection, members work to call attention to random arrests, decry human rights violations of those imprisoned, and seek the release of jailed MRTA leaders (Baer 2003).

Each of the conflicts that have occurred in Peru is ideological in nature, with various forms of identity woven throughout. This complicates the typical tactical choice assumptions that have been made to this point. Ideological battles over the state are likely to be particularly intense and enduring. That is certainly true for Sendero Luminoso, although less so for MRTA. It was not the case for the ELN or MIR. These groups, however, lacked the capacity of Sendero, which is discussed further below. The nature of these groups suggests that both the rebels and the government are less likely to compromise. This has certainly been the case. The intransigence may also be a function of the complex ideological/ identity nexus. Sendero Luminoso employed extreme views of identity, drawing a clear line between those on the side of the movement and those working against it. The us-versus-them dichotomy both helped and hurt group capacity building, as discussed below, but it also made terrorist tactics an option despite the typically natural combination of ideological causes and guerrilla warfare.

To understand the brutal tactics employed by Sendero more fully, it is essential to understand the foundation on which the organization is based and how it emerged. Guzman was prevented from joining the Communist Party in Peru as a student in Arequipa because he was not a child of a worker, which he explained was a “serious mistake” (Guzman 1993, 52). This would appear to be the beginning of Guzman’s discontent with the policies and approaches of the Peruvian left, particularly those who aimed to work with reformist government leadership. According to Guzman, “I evaluated the party situation: Revisionism continued and we could make no progress unless it was wiped out” (56). By the late 1960s, Guzman thought it necessary to create this “Red Faction” utilizing revolution to bring a true government to Peru (Guzman 1993) without foreign interference. Guzman viewed all Peruvian governments since Spanish colonialism as illegitimate (Manwaring 1995). His 1975 trip to China solidified his approach, making Sendero Luminoso distinct by embracing Maoist ideology. He also maintained a steadfast unwillingness to compromise his ideals of a cohesive, revolutionary front led by him. According to Manwaring (1995), the primary objective of Guzman was power, and gaining that required discipline, intelligence, and motivation. The training of Sendero Luminoso revolutionaries was methodical and focused on creating a loyal set of followers with a centralized core that Guzman ruled through fear (Burgoyne 2010; Onís et al. 2005). His previous experience with leftist rivals and his lack of compromise in the area of ideology and loyalty made for an organization with a clear us-versus-them mentality. To not pledge loyalty to the organization made one an opponent and a threat—and, therefore, a target. Under such conditions, rival organizations, such as MRTA and unsupportive peasants, became targets.

The government, for its part, was quite willing to target civilians as well. Its disregard for the civilian population can be explained in large part by identity. Whether an individual was Indian, Quechua speaking, rural peasant, or leftist, all were considered fair game in the armed struggle against Peru’s insurgents.

Leftist opposition to the Peruvian government had a large population of sympathizers from which to draw membership due to the vast inequality in the system. Not all groups were able to harness this support and improve their capacity with numbers. The first two armed factions of Peru involving the ELN and the MIR were rather small in size and lacked organizational capacity (UCDP/PRIO 2014). Héctor Béjar (1969), a former leader in the ELN, examined his experience from prison shortly following the 1965 insurrection. Although the Peruvian army was fifty thousand strong, both the MIR and the ELN were working with small bands, as few as thirteen rebels. These were separated by distance, however, making communication between the various fronts difficult. According to Béjar, “when Lobaton [one of the MIR fronts] opened fire in June, de le Puenta [another front] was still not prepared and the northern front had not even begun its operations” (Béjar 1969, 79). This disconnect further handicapped these already small groups.

What the ELN lacked in armed members, it attempted to make up for with support among the community indigenous to the region in which the group operated. Having been exploited by fraudulent lawyers, judges, and landowners, the impoverished population of the Ayacucho region was indeed welcoming to guerrillas working to return communal lands. As Béjar indicates, wherever the rebels traveled in this region, they found friends. Rebels with significant sympathy among the population can potentially survive even if small in size. In order to grow and engage the government in larger battles, the ELN needed to convert sympathizers into rebels. Identity differences between the city dwellers taking up arms and the indigenous rural peasant farmers they sought to protect were too great. Further, the ELN underestimated the government’s willingness to repress sympathizers. As Béjar indicates, “when the invasion finally comes, all of our supporters are tortured and shot” (Béjar 1969, 101). Although the ELN was able to work the mountainous and jungle terrain to its advantage somewhat, staying hidden in this region depends on secrecy. The Peruvian military readily utilized torture and repression on the indigenous population to find the rebels. Ultimately, these small bands of rebels were surrounded and exterminated or arrested. This experience helped form part of the historical memory for the indigenous peoples in the Andean region.

FIGURE 7.5 Patterns of Violence in Peru, 1982–2008

The MIR, operating simultaneously, suffered a similar experience. Neither the ELN nor the MIR was large enough or organized in a way that allowed for surviving the government’s response to their mobilization. The two early factions never coordinated their activities to improve their organizational capacity vis-à-vis the government. Despite their size, both chose to engage the government in guerrilla warfare and were quickly surrounded. As a result, they were both short-lived affairs culminating in an estimated 138 total battle-related deaths in 1965 (Lacina and Gleditsch 2005).

Sendero Luminoso and MRTA were both better organized and larger in size than their predecessors. They were also able to draw upon available resources to ensure longer survival. Sendero was the largest of the rebel factions and, as a result, the most successful. Estimates of the size of Sendero Luminoso suggest the organization could claim as many as eight thousand armed members (Cunningham, Gleditsch, and Salehyan 2009), though other estimates suggest it was larger (Gregory 2009). It attacked towns and government forces in bands as large as seven hundred (Keesing’s World, May 1983). Because it enjoyed significant numbers, it is not surprising that Sendero was the only faction in Peru that was able to engage directly in armed conflict with the government. It successfully employed guerrilla warfare early on, particularly as the government underestimated its strength and dedicated only a small fraction of its force to counter the Sendero threat.

Sendero Luminoso’s relationship with the peasants it sought to save from the oppressive poverty discussed above has been complicated. Early in the campaign, Sendero enjoyed a significant amount of passive support (Berg 1994). Employing the indoctrination training mentioned above, Sendero was able to expand its membership well beyond its predecessors. Having formed at the University of Huamanga, the organization benefited from a significant number of sympathizers who, though educated, were unable to improve their lot in life. Unlike the experience of the ELN, some of these sympathizers took up arms and joined the cause. Of course, not all Sendero Luminoso supporters participated in the insurrection freely. The organization took a zero sum approach to its campaign. In the view of the rebels, indigenous peasants were either supporting the organization or the government, which made such traitors a target for reprisals in much the same way the government had done in past rivalries and would continue to do again in its battle to eliminate the Sendero rival. As a result, the conflict involved massive, well-documented human rights abuses. Membership and Sendero sympathy were also undermined by the group’s ideologically driven efforts to transform indigenous societies. Rather than seeing themselves as participants in a revolution, the poor were once again victims of external aggressors (Isbell 1994). Despite a large amount of frustration on the part of the poor in Peru, the membership of Sendero, though large, was actually undercut by the group’s policies and the atrocities it committed in the name of its cause. As was the case in the previous 1965 rivalries, the government contributed to this problem further. By the mid-1980s, indigenous peasants were organized into their own security forces to protect themselves against Sendero Luminoso. The government encouraged this to the extent that President Belaunde offered medals to peasants who killed terrorists (Keesing’s World, May 1983).

At its height in the 1980s, MRTA was approximately two thousand strong (Baer 2003). Unlike the other armed factions in Peru, MRTA did not engage in guerrilla warfare. MRTA’S tactics were carefully aimed at achieving its goals, which were “to create a new society in which all people were treated equally, enjoyed the same opportunities and level of prosperity, and shared ownership of all property” (Baer 2003, 4). MRTA leadership focused much of its activity on foreign, particularly U.S., interests that it blamed for persistent inequality and poverty in Peru. Its tactics have included bombing or small arms attacks on the U.S. embassy in Lima, hijacking food trucks that it then used to feed the poor, and, later, kidnapping foreign executives for ransom (Baer 2003). As a result, MRTA members did not require significant armaments. These tactics are clearly terrorist in nature. Interestingly, however, MRTA was careful to avoid civilian casualties by frequently calling in warnings of attacks and suggesting that buildings be evacuated. Rather than seeking to take over the government through force, MRTA aimed to gain attention for its causes.

Both MRTA and Sendero attempted to increase their strength in 1987 by shifting their area of operations. MRTA, which had emerged out of Lima, moved to embrace a “new strategy of rural guerrilla operations,” paying homage to revolutionary leader Che Guevara (Keesing’s World, February 1988). The organization, led by Victor Polay, raided the towns of Juanjui and San Jose de Sisa in the Upper Huallaga Valley. In the same year, Sendero Luminoso intensified its drive for political support by increasing its urban operations (Keesing’s World, February 1988). The decision by MRTA to shift toward guerrilla tactics in the more remote Upper Huallaga Valley required additional resources. It has been suggested that it was here that MRTA members began to cooperate with coca producers. Sendero Luminoso already dominated this market by the time MRTA made its entrance, however.

Once again, a contradiction emerged in examining conflict involving Sendero Luminoso. The Peruvian government has benefited greatly from U.S. efforts to address the drug trade. The United States has trained antidrug agents in Peru, while providing assistance to destroy coca crops and encourage coca growers to substitute less lucrative options for drug crops. Although this assistance was intended to bolster the government’s capacity, this was not necessarily what occurred. Efforts to eradicate coca and pursue rebels threatened peasant farmers’ livelihood. In the end, the peasant farmers were willing to support whichever group would secure their economic livelihood (Gonzales 1994). As a result, a guerrilla-farmer security relationship emerged. Sendero was able to obtain the financial support its members needed, and the peasant farmers were protected from government efforts and policy.

Although the MRTA and Sendero factions coincided with one another, as was the case with the MIR and the ELN, the two never cooperated. To the contrary, the organizations worked against one another. MRTA took issue with Sendero policy of “selective killings,” while Sendero Luminoso turned its back on, or targeted, all leftist groups that did not embrace its revolutionary, “ideologically pure” approach (Washington Post 1988).

Despite the lack of cooperation these rivals displayed, both were at their strongest in the late 1980s. Their success at this time coincided with a further deterioration of the Peruvian economy. Inflation, increasing debt, and loan defaults, along with crippling austerity programs, fed the population’s dissatisfaction with its leadership. The Peruvian government appeared particularly inept at dealing with both the insurgencies and the economic crisis. This changed, however, with the election of Alberto Fujimori in 1990. Fujimori embarked on a severe austerity program that was able to rein in the triple-digit inflation and replenish government revenue (CQ Press 2009a). In addition, he launched a new counterterrorist effort that included a dramatic increase in its rural defense patrols (CQ Press 2009a) while introducing new antiterrorism laws (which were later ruled unconstitutional). This led to the capture of Sendero’s Guzman in September 1992 and MRTA’S Polay in 1993, along with other Sendero and MRTA leaders.

Both MRTA and Sendero Luminoso survived these arrests, but in significantly weaker states. The arrest of Guzman was particularly crippling for Sendero. The indoctrination training employed by the group provided a highly structured organization. Guzman was painstakingly careful in structuring the organization so that he would be the central figure of Sendero Luminoso (Gorriti 1999). This meant the group would benefit significantly from its cohesion. Rumors of potential splintering were rare (see Keesing’s World, May 1990, as an example). But such a structure also meant that by arresting the rebel group’s leadership the government had rather effectively decapitated the organization. Attacks by Sendero members continued, but at a dramatically reduced rate. It is at this time that Guzman and other Sendero members called for peace from their jail cells (Keesing’s World, January 1994). This shift in tactics brought about a splinter faction of Sendero Luminoso, which refers to itself as the Red Faction, or Sendero Luminoso Rojo. Remnants of Sendero, approximately several hundred strong, continued to operate in the Upper Huallaga, Apurimac, and Ene River Valleys (Sullivan 2010). The armed conflict has not resulted in more than twenty-five battle-related deaths since 2010, however. This may be due in part to the group’s shift in priorities. The region in which they reside is particularly suited for coca plantations. While still employing ideology as a tool of indoctrination, the rebellion has become more of a series of profit-seeking organizations proficient in money laundering for terrorist organizations (De Angelis 2015) than a revolutionary movement. In order to ensure continued survival, the group enslaved approximately two hundred people, particularly from the Ashaninka ethnic group. By using systematic rape and continued indoctrination of children born of rape, the group is literally growing its army. The government renewed its campaign, once considered dead, in 2015, capturing two Sendero leaders and freeing fifty-four slaves, thirty-three of which were children (Martel 2015).

The MIR, ELN, and Sendero Luminoso each sought to bring about revolution in Peru. The ELN was inspired by the Cuban Revolution, whereas the MIR was frustrated by the APRA’S decision to reject communism entirely. It is not surprising that both groups took their fight to the rural, mountainous areas of Peru and engaged in guerrilla warfare. Sendero Luminoso also clearly wanted to bring Peru under Communist rule of its own making. It too took its fight to the mountains. Interestingly, however, despite Guzman’s embrace of Maoist philosophy, the very people the Sendero group claimed to want to help became frequent targets. Mao claimed that to win the revolution, the revolutionaries needed to win the hearts and minds of the peasants. Guzman attempted to do this through indoctrination, often forced. The rebels’ commitment to the Sendero ideology and its approach left no room for compromise. As a result, political avenues to address inequality in Peru were eliminated at the onset. Further, any leftist organization that attempted to do work politically, or any person who participated in elections, became an enemy. Rather than working with and embracing exploited workers and peasants, Sendero revolutionaries attempted to dominate them and impose their views and approach them often through force. Guerrilla warfare, as a result, relied heavily on terrorizing the Peruvian civilian population.

The theoretical model presented in chapter 1 suggests that groups and governments learn from their experiences and adjust their approaches in light of their successes or failures in previous interactions. Guzman appeared to have learned from the experience of the ELN and the MIR. Sendero took its time and effectively prepared to emerge as a revolutionary force. Its organizational capacity far exceeded that of its predecessor. What it did not overcome, however, were the various identity-based divisions in Peru. Sendero was able to find common ground with the peasant farmer in the Huallaga Valley, but for the most part, Sendero’s tactical approach with the peasantry remained unchanged through the 1980s.

The shift by Sendero from an entirely rural approach to one that included an urban strategy appears to have come about by the limitations of the rural-only strategy. Competing leftist organizations, particularly MRTA, were making headway in the coastal urban areas. Ignoring this capacity-growing potential was to the detriment of each group’s long-term goals. The same can be said of MRTA’S shift toward the rural areas. What neither group could come to terms with, however, was overcoming their intergroup differences. Given the vast inequality in Peru, both historically and at the time of insurrections, the country was ripe for revolution. This is evident by the number of leftist groups that emerged over time. The differences among them and the fighting between them did not allow for cooperative endeavors.

There is evidence that the government learned from its mistakes, although its anti-insurgency campaigns were never truly successful. Under General Velasco, the military regime worked to address the issue of internal peace by implementing a series of structural reforms aimed at alleviating chronic poverty and underdevelopment in the mountainous regions where much of the indigenous population lives (“Military Reform” 1992; Champion 2001). The efforts were well received initially, at least by the poor and leftist groups, but they ultimately failed as a result of ineffective economic policy. The result was economic collapse, which only stimulated more insurrection. Subsequent efforts to alleviate the sources of intrastate conflict have been comparatively successful. The poverty rate in Peru in 2011 was 27.8 percent (Peruvian Times 2012). This has reduced the attractiveness of taking up arms and engaging in revolution, although the regional divide remains. The 2011 poverty rate for the rural population of Peru was 56.1 percent (Peruvian Times 2012).

The Peruvian government also shifted its antiterrorism tactics over time. The most notable was Fujimori’s decision to strengthen antiterrorism laws. He also was able to improve intelligence, which allowed for the arrest or killing of key leadership of MRTA and Sendero Luminoso. Further, the 1992 Repentance Law allowed rebel group members to surrender for lenient or suspended sentences in exchange for turning over names of other guerrillas. The United Nations has indicated that 5,516 Sendero members and 814 MRTA members took advantage of the law (Human Rights Watch 1995a). The actions of these arrepentidos resulted in many arbitrary imprisonments, as those repenting did not have to provide much in the way of evidence, but it also significantly weakened both insurgencies.

Despite counterterrorist and poverty reduction efforts, Sendero Luminoso remains active primarily in the rural parts of Peru and seems more attached to the drug trade than its political goals (Skeen n.d.), while MRTA members continue to advocate for the more humane treatment of prisoners. The persistence of these groups can be explained in large part by the pervasive poverty and inequality in Peru. Despite the targeting of civilians by Sendero Luminoso, those suffering the most have not been able to trust the government either. Grievances remain. The failure of earlier factions to address this problem was a function of the lack of group capacity relative to the government. A terrain ripe for guerrilla warfare can actually be a detriment for groups that are too small to communicate effectively over large, dense terrain.

Unlike other cases examined in this book, intrastate conflict in Peru has not been influenced dramatically by outside intervention. Although the United States does unknowingly benefit Sendero Luminoso when it helps Peru with crop eradication and substitution, diplomatic or military efforts by external actors appear to have been entirely absent. In this regard, capacity by armed groups is in large part dependent on what resources they can capture or whose sympathies they can garner. Sendero has done well in this regard, utilizing terrain to its advantage as well as capturing revenues from the drug trade. MRTA, in choosing not to target civilians, has been able to endure because of its tactical approach and the sympathy it has gained for its cause.