Engraving and printing of The Art of Fugue

Since the engraving process of copper plates requires handwritten engraver copies, the identity of their transcribers can be determined with considerable accuracy. Studies ascertain the active involvement of Johann Sebastian Bach in the preparation of the engraver copies, himself writing those for 11 items in The Art of Fugue:11 Contrapuncti 1, 2(?), 3, 4, 11, 122, [13]2,12 as well as all four canons. His son, Johann Christoph Friedrich, wrote the engraver copies of the eight Contrapuncti 5(?), 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 121, and [13]1. The person(s) who prepared the engraver copies of the four Contrapuncti [10a],13 [181] (Fuga a 2. Clav:), [182] (Alio modo. Fuga a 2. Clav.) and [19] (Fuga a 3 Soggetti) as well as of the choral setting Wenn wir in hoechsten Noethen sein still has not been established.14 It is only known that they were written after Bach’s death, in the period of preparation of The Art of Fugue’s edition, probably in the winter of 1750–51.

Unfortunately, there is no direct information that Carl Philipp Emanuel proofread the sample printouts. While his list of errata in the 1751 edition is written on the blank verso of the fourth sheet in P 200/1–3,15 the ‘unfinished’ fugue, it is impossible to establish a link between this list and either the sample proofreading sheets or the published edition.

It is known, however, that Johann Sebastian took particular care of the sample proof sheets when preparing The Art of Fugue edition for print. Johann Christoph Friedrich Bach’s inscription on the engraving copy of the Canon in Augmentation (P 200/1–1) tells about his late father’s proofreading of the sample printouts of The Art of Fugue and making the necessary amendments himself.16

Where was the printing performed?

The place where The Art of Fugue was printed has not yet been established. Klaus Hofmann, summarising years of multiple efforts in Bach studies, had to conclude: ‘Die näheren Umstände der Drucklegung der Kunst der Fuge sind unbekannt’ [The details of the circumstances surrounding the print of The Art of Fugue are unknown.]17 However, at least three places can certainly be identified as having some relation to this process: Zella, Berlin and Leipzig.

Schübler’s engravings, made out of engraving copies prepared by Johann Sebastian and Johann Christoph Friedrich Bach, took place in Zella. However, while it is possible that the sample prints were issued there, it seems that the run printing was not performed in that town. It is hard to believe that Zella had sufficient printing capacities: else, the whole run printing would be done there, too. As a reminder, four years earlier the Musical Offering was engraved in Zella, too, but its run printing was performed in Leipzig. The Art of Fugue required even more printing resources than the Musical Offering.

Another possible printing place for The Art of Fugue is Berlin, the residing place of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach and Johann Friedrich Agricola, who managed the whole publication process. The fact that Emanuel was deeply involved in this process is beyond doubt, since he was the one who initiated and drafted all the newspaper announcements about the Original Edition. It is known that he did not leave Berlin during the period of publication, that is, from the end of November 1750 to the beginning of 1751. He owned and kept the Autograph and all the supplements,18 and it was in his house that almost all the engraved copper plates were later offered for sale to interested music publishers.19 However, circumstantial evidence indicates that Berlin was not the place of printing and publication of The Art of Fugue.

First, as Georg Kinsky shows,20 the important introductions to two publications—the Musical Offering (the title page and the dedication to the King) and the 1752 edition of The Art of Fugue (the title page and the Preface)—were not engraved, but typeset with the cast sorts of the Breitkopf Publishing Company in Leipzig. Furthermore, the music pages were printed on the same kind of paper as the title page of the 1752 The Art of Fugue, which would be too much of a fortuitous coincidence, were they printed in two different cities. Second, it is documented that on May 19, 1752, Anna Magdalena Bach brought to the Magistrate of Leipzig several copies of The Art of Fugue.21 This was most probably the fresh edition of 1752. Finally, as already mentioned, both editions were prepared to coincide with the Leipzig Fairs.22 It is likely, therefore, that at least the second edition was printed in Leipzig. As for the first (1751) edition, there are still many unclear points. On one hand, the above considerations point to Leipzig; on the other hand, the letterset of the title page and the Preface of the 1751 edition is not identical, and it is yet not established whether Breitkopf used it or not.

Since the editions of 1751 and 1752 are printed on different types of paper,23 one could argue that one of the editions might have been printed in Berlin and the other in Leipzig. However, were the first edition printed in Berlin and not in Leipzig, it would entail a rather unwieldy transfer of the engraved copper plates: more than 60 plates, about a hundredweight24 of copper, about 175 miles northeast from Zella to Berlin, then about 90 miles southwest from Berlin to Leipzig, and then back northeast to Berlin, a cumbersome total distance of 355 miles. It would thus seem more feasible to travel the approximate distance of 85 miles northeast from Zella to Leipzig and then continue in the same direction, another 90 miles, to Berlin, less than half the distance of the latter route, which even without taking into account the awkward and partly fragile load would logically be a preferred one. Such a choice, however, would locate the 1751, first edition, in Leipzig, and the 1752 second one in Berlin. Yet, it was the Leipzig edition that appeared in 1752.

Thus, there is not enough direct proof for affirming that it is Leipzig where both editions of The Art of Fugue were printed. Nevertheless, such a conclusion could be quite reasonable within the wider context of direct and indirect information. Klaus Hofmann, for example, writes: ‘Als Druckort kommt in erster Linie Leipzig’.25 Christoph Wolff shares this opinion and even more decisively names Leipzig as the location where both editions of The Art of Fugue were printed.26

Thus, the following unfolding of events concerning the publication of The Art of Fugue can be tentatively drafted. Based on the known facts and whereabouts of the individuals that had a role in the publication process, it becomes apparent that Johann Heinrich Schübler from Zella dealt just with the engraving, that is, with the preparation of the 67 copper plates. Thereafter, they were all transported to Leipzig for the printing of (probably) both editions, and eventually sent to Berlin, to Emanuel.

Carl Philipp Emanuel, in all likelihood, was the one responsible for writing the engraving copies of the pieces located on the edition’s pages 45–7 and 57–67 (Contrap: a 4; Fuga a 2 Clav:; Alio modo, Fuga a 2 Clav.; Fuga a 3 Soggetti; Choral. Wenn wir in hoechsten Noethen sein), which he sent to Zella. He provided the general design of the whole collection and further took upon himself the advertising of the edition, taking advantage of his connections among both enlightened and merchant circles and drafting practically all the related announcements and notices. Finally, he wrote the preface to the first edition, although it is possible that Johann Friedrich Agricola helped him in that.

As for Anna Magdalena Bach, her participation in preparing the fair and/or the engraver copies for The Art of Fugue—either when Bach was still alive or in a later stage of the publishing process—has left no trace. Most probably, her mission was limited to maintaining contacts with the Breitkopf publishing house and printing press.

Wilhelm Friedemann Bach left no evidence of immediate involvement in writing any kind of copies. Also, there is no indication of Altnickol being connected with this project. On the other hand, Agricola probably assisted C.P.E. Bach in preparing The Art of Fugue for print.

Two editions

As already mentioned, the publications of 1751 and 1752 differ only in their title pages and prefaces. The title pages of the two editions carry identical texts, in slightly different designs. The letters are larger in the 1752 edition, and the text is spread over seven lines rather than five. The two prefaces, however, differ significantly. The preface to the 1751 edition is titled Nachricht, and is printed on the verso of the title page:

Der selige Herr Verfasser dieses Werkes wurde durch seine Augenkrankheit und den kurz darauf erfolgten Tod ausser Stande gesetzet, die letzte Fuge, wo er sich bey Anbringung des dritten Satzes namentlich zu erkennen giebet, zu Ende zu bringen; man hat dahero die Freunde seiner Muse durch Mittheilung des am Ende beygefügten vierstimmig ausgearbeiteten Kirchenchorals, den der selige Mann in seiner Blindheit einem seiner Freunde aus dem Stegereif in die Feder dictirert hat, schadlos halten wollen.27

[Notice.

The late Author of this work was prevented by his disease of the eyes, and by his death, which followed shortly upon it, from bringing the last fugue, in which at the entrance of the third subject he mentions himself by name (in the notes B A C H, i.e., B![]() A C B

A C B![]() ), to conclusion; accordingly it was wished to compensate the friends of his muse by including the four-part church chorale added at the end, which the deceased man in his blindness dictated on the spur of the moment to the pen of a friend.]28

), to conclusion; accordingly it was wished to compensate the friends of his muse by including the four-part church chorale added at the end, which the deceased man in his blindness dictated on the spur of the moment to the pen of a friend.]28

The preface to the 1752 printing (here titled Vorbericht) is signed by Friedrich Wilhelm Marpurg. It has been expanded into two full pages and carries an additional remark: ‘in der Leipziger Ostermeße / 1752’ [during the Leipzig Easter Fair / 1752.]29

The music in the Original Edition

As indicated above, the musical text in the Original Edition is identical in both 1751 and 1752 prints. However, when the edition is compared with the Autograph, significant differences emerge:

• Six compositions that appear in the Original Edition are absent from the Autograph:

• Contrapunctus 4

• Contrapunctus 10. a. 4. Alla Decima

• Canon alla Decima Contrapunto alla Terza

• Canon alla Duodecima in Contrapunto alla Quinta

• Fuga a 3 Soggetti

• Choral. Wenn wir in hoechsten Noethen … Canto Fermo in Canto

• The compositions in the Original Edition have different titles than those appearing in the Autograph. The first 14 compositions in the edition are fugues. While the fugues in the Autograph are just numbered (as a reminder, J.S. Bach numbered only the first eight), those in the edition are all titled Contrapunctus (Contrapunctur30 for the fifth fugue) except for the 14th, which is titled Contrap: a 4. Additionally, fugues 1–12 are also numbered.31

• The remaining three fugues appear in the edition after the presentation of the canons. They are not numbered and use Fuga in their titles:

• Fuga a 2 Clav:

• Alio modo. Fuga a 2. Clav.

• Fuga a 3 Soggetti

• The first four fugues and the last one (Fuga a 3 Soggetti) have no indication of the number of voices.

• The canons are not numbered. To indicate the interval in which the second part enters, Italian designations were used (Ottava, Decima, Duodecima), while in the Autograph the designations are Greek (Hypodiapason, Hypodiateßeron).

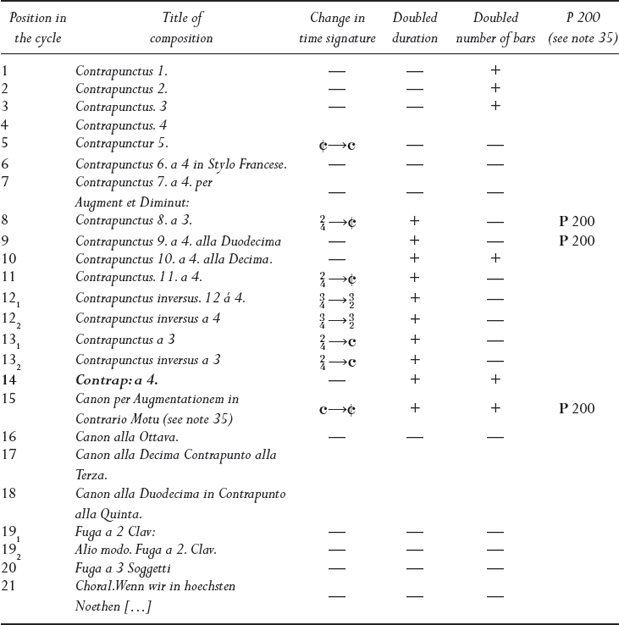

• The order of compositions in the Original Edition differs from their order in the Autograph (see Scheme 5.1). The order of compositions and their titles in the entire cycle is shown in Table 5.1.

• In the Autograph, only the canons are supplied with textual comments:

• Canon in Hypodiapason

• Resolutio Canonis

• Canon in Hypodiateßeron. al roversio e per augmentationem, Perpetuus

• Canon al roverscio et per augmentationem

• Several fugues, however, have additional textual comments (see below).

Other differences relate to the general layout.

• The Original Edition has an unusual pagination system, which starts not from the title page, as does the Autograph, but from the left page of the first spread. Consequently, the odd numbers appear on the verso pages while the even numbers on the recto ones.

• The fragment of the ‘unfinished’ triple fugue’s presentation in the Original Edition differs from that of the Autograph (P 200/1–3) in three elements. First, it is titled Fuga a 3 Soggetti in the edition, while in the Autograph it has no title; second, in the Autograph the fugue is written in a two-stave clavier layout while in the edition it is presented in a four-stave score; finally, in the Original Edition, the seven last bars of this fugue, as it appears in the Autograph, are missing. Most probably, Emanuel made all these changes.

Table 5.1 Order of pieces in the Original Edition (in bold: not in the Autograph)

| Position in the cycle | Title of composition |

| 1 | Contrapunctus 1. |

| 2 | Contrapunctus 2. |

| 3 | Contrapunctus 3 |

| 4 | Contrapunctus. 4 |

| 5 | Contrapunctur 5. |

| 6 | Contrapunctus 6. a 4 in Stylo Francese. |

| 7 | Contrapunctus 7. a 4. per Augment et Diminut: |

| 8 | Contrapunctus 8. a 3. |

| 9 | Contrapunctus 9. a 4. alla Duodecima |

| 10 | Contrapunctus 10. a. 4. alla Decima. |

| 11 | Contrapuntus. 11. a 4. |

| 121 | Contrapunctus inversus. 12 á 4. |

| 122 | Contrapunctus inversus a 4 |

| 131 | Contrapunctus a 3 |

| 132 | Contrapunctus inversus a 3 |

| 14 | Contrap: a 4. |

| 15 | Canon per Augmentationem in Contrario Motu. |

| 16 | Canon alla Ottava. |

| 17 | Canon alla Decima Contrapunto alla Terza. |

| 18 | Canon alla Duodecima in Contrapunto alla Quinta. |

| 191 | Fuga a 2 Clav: |

| 192 | Alio modo. Fuga a 2. Clav. |

| 20 | Fuga a 3 Soggetti |

| 21 | Choral. Wenn wir in hoechsten Noethen sein. Canto Fermo in Canto). |

Changes in rhythm and metre

The changes between the Autograph and the Original Edition involve not only the number of works in the set, their ordering and layout, but also modifications of the music itself: change of metre, double rhythmic values, double number of bars, addition of bars and the reworking of a one-theme simple contrapunctus into a double fugue.

• The metre of most fugues (Contrapuncti 1, 2, 3, 8, 9, 11, 12, [13] and [14]) and of the Canon per Augmentationem in Contrario Motu was changed in the Original Edition in comparison with the Autograph.32 Consequently, these pieces (except the first three) have doubled rhythmic values in the edition.

• Contrapuncti 1, 2, 3 and 10 underwent further changes on their way to the Original Edition, including additional musical fragments. In the first three fugues these modifications were limited to several extra bars in the cadenza. In Contrapunctus 10, however, the simple (monothematic) fugue with the regular countersubject was re-worked into a double one. The Original Edition includes both Contrapuncti 10 (the re-worked variant) and [14] (the Autograph version with the augmented rhythmical values that doubled the number of bars).

• While the two mirror fugues (Contrapuncti 121, 2 and [13]1, 2) have their metre changed in relation to the Autograph  , the third mirror fugue (Fuga a 2. Clav in both rectus and inversus), that had been derived from the second one, did not undergo such a transformation.33 This particular case requires special explanations and leads to a discussion relevant not only to the mirror fugues but to the entire cycle.

, the third mirror fugue (Fuga a 2. Clav in both rectus and inversus), that had been derived from the second one, did not undergo such a transformation.33 This particular case requires special explanations and leads to a discussion relevant not only to the mirror fugues but to the entire cycle.

Table 5.2 shows that transformations of metre and rhythm from the Autograph to the Original Edition are the rule rather than an exception.34 The following types of changes in metre and rhythm are found in the Original Edition:

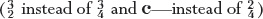

• Doubled metre with no rhythmic or bar number modifications. Such is Contrapunctur 5 (in the Autograph it is fugue IV), where the metre ![]() in the Autograph is replaced by

in the Autograph is replaced by ![]() , though neither rhythmic values nor number of bars changed in the fugue.

, though neither rhythmic values nor number of bars changed in the fugue.

• Changed metre and doubled rhythmic values, leaving the bar numbers intact, happen in Contrapuncti 8, 11,121, 122, [13]1 and [13]2.

• The rhythmic values and bar number were doubled in Contrapuncti 9 and 10 while their metre was left intact.

• In the first three contrapuncti, the number of bars was doubled but the metre and rhythmic values remained unchanged.

As follows from the Original Edition and Table 5.2, all metre and rhythm changes were performed when Bach was still alive and—evidently—on his initiative, while Emanuel did not intervene at all in Bach’s text.