1 Why ask an archaeologist about the human mind?

THE HUMAN MIND is intangible, an abstraction. In spite of more than a century of systematic study by psychologists and philosophers, it eludes definition and adequate description, let alone explanation. Stone tools, pieces of broken bone and carved figurines – the stuff of archaeology – have other qualities. They can be weighed and measured, illustrated in books and put on display. They are nothing at all like the mind – except for the profound sense of mystery that surrounds them. So why ask an archaeologist about the human mind?

People are intrigued by various aspects of the mind. What is intelligence? What is consciousness? How can the human mind create art, undertake science and believe in religious ideologies when not a trace of these are found in the chimpanzee, our closest living relative?1 Again one might wonder: how can archaeologists with their ancient artifacts help answer such questions?

Rather than approach an archaeologist, one is likely to turn to a psychologist: it is the psychologist who studies the mind, often by using ingenious laboratory experiments. Psychologists explore the mental development of children, malfunctions of the brain and whether chimpanzees can acquire language. From this research they may offer answers to the types of questions posed above.

Or perhaps one would try a philosopher. The nature of the mind and its relation to the brain – the mind-body problem – has been a persistent issue in philosophy for over a century. Some philosophers have looked for empirical evidence, others have simply brought their considerable intellects to bear on the subject.

There are other specialists one might approach. Perhaps a neurologist who can look at what actually goes on in the brain; perhaps a primatologist with specialized knowledge of chimpanzees in natural, rather than laboratory, settings; perhaps a biological anthropologist who examines fossils to study how the brain has changed in size and shape during the course of human evolution, or a social anthropologist who studies the nature of thought in non-Western societies; perhaps a computer scientist who creates artificial intelligence?

The list of whom we might turn to for answers about the human mind is indeed long. Maybe it should be longer still with the addition of artists, athletes and actors – those who use their minds for particularly impressive feats of concentration and imagination. Of course the sensible answer is that we should ask all of these: almost all disciplines can contribute towards an understanding of the human mind.

But what has archaeology got to offer? More specifically, the archaeology to be considered in this book, that of prehistoric hunter-gatherers? This stretches from the first appearance of stone tools 2.5 million years ago to the appearance of agriculture after 10,000 years ago. The answer is quite simple: we can only ever understand the present by knowing the past. Archaeology may therefore not only be able to contribute, it may hold the key to an understanding of the modern mind.

Creationists believe that the mind sprang suddenly into existence fully formed. In their view it is a product of divine creation.2 They are wrong: the mind has a long evolutionary history and can be explained without recourse to supernatural powers. The importance of understanding the evolutionary history of the mind is one reason why many psychologists study the chimpanzee, our closest living relative. Numerous studies have compared the chimpanzee and human mind, notably with regard to linguistic capacities. Yet such studies have ultimately proved unsatisfactory, because while the chimpanzee is indeed our closest living relative, it is not very close at all. We shared a common ancestor about 6 million years ago. After that date the evolutionary lineages leading to modern apes and humans diverged. A full 6 million years of evolution therefore separates the minds of modern humans and chimpanzees.

It is that period of 6 million years which holds the key to an understanding of the modern mind. We need to look at the minds of our many ancestors3 during that time, including the 4.5-million-year-old ancestor known as Australopithecus ramidus; the 2-million-year-old Homo habilis, among the first of our ancestors to make stone tools; Homo erectus, the first to leave Africa 1.8 million years ago; Homo neanderthalensis (the Neanderthals), who survived in Europe until less than 30,000 years ago; and finally our own species, Homo sapiens sapiens, appearing 100,000 years ago. Such ancestors are known only through their fossil remains and the material residues of their behaviour – those stone tools, broken bones and carved figurines.

The most ambitious attempt so far to reconstruct the minds of these ancestors has been by the psychologist Merlin Donald. In his book The Origins of the Modern Mind (1991), he drew substantially on archaeological data to propose a scenario for the evolution of the mind. I want to follow in Donald’s footsteps, although I believe he made some fundamental errors in his work – otherwise there would be no need for this book.4 But I want to turn the tables on Donald’s approach. Rather than being a psychologist drawing on archaeological data, I am writing as an archaeologist who wishes to draw on ideas from psychology. Rather than having archaeology play the supporting role, I want it to set the agenda for understanding the modern mind. So here I provide The Prehistory of the Mind.

The last two decades have seen a remarkable advance in our understanding of the behaviour and evolutionary relationships of our ancestors. Indeed many archaeologists now feel confident that the time is ripe to move beyond asking questions about how these ancestors looked and behaved, to asking what was going on within their minds. It is time for a ‘cognitive archaeology’.5

The need for this is particularly evident from the pattern of brain expansion during the course of human evolution and its relationship – or the lack of one – to changes in past behaviour. It becomes clear that there is no simple relationship between brain size, ‘intelligence’ and behaviour. In Figure 1 I depict the increase in brain size during the last 4 million years of evolution across a succession of human ancestors and relatives whom I will introduce more fully in the next chapter. But here just consider the manner in which brain size increased. We can see that there were two major spurts of brain enlargement, one between 2.0 and 1.5 million years ago, which seems to be related to the appearance of Homo habilis, and a less pronounced one between 500,000 and 200,000 years ago. Archaeologists tentatively link the first spurt to the development of toolmaking, but can find no major change in the nature of the archaeological record correlating with the second period of rapid brain expansion. Our ancestors continued the same basic hunting and gathering lifestyle, with the same limited range of stone and wooden tools.

The two really dramatic transformations in human behaviour occurred long after the modern size of the brain had evolved. They are both associated exclusively with Homo sapiens sapiens. The first was a cultural explosion between 60,000 and 30,000 years ago, when the first art, complex technology and religion appeared. The second was the rise of farming 10,000 years ago, when people for the first time began to plant crops and domesticate animals. Although the Neanderthals (200,000–30,000 years ago) had brains as large as ours today, their culture remained extremely limited – no art, no complex technology and most probably no religious behaviour. Now big brains are expensive organs, requiring a lot of energy to maintain – 22 times as much as an equivalent amount of muscle requires when at rest.6 So here we find a dilemma – what was all the new brain processing power before the ‘cultural explosion’ being used for? What was happening to the mind as brain size expanded in the two major spurts during human evolution? And what happened to it between these spurts, and to the mind of Homo sapiens sapiens to cause the cultural explosion of 60,000–30,000 years ago? When did language and consciousness first arise? When did a modern form of intelligence arise – what indeed is this intelligence and the nature of the intelligence that preceded it? What are the relationships of these, if any, to the size of the brain? To answer such questions we must reconstruct prehistoric minds from the evidence I introduce in Chapter 2.

1 The increase in brain volume during the last 4 million years of human evolution. Each symbol denotes a specific skull from which brain volume has been estimated by Aiello & Dunbar (1993). Upper graph based on figure in Aiello (1996a) who discusses the evidence for the two bursts of brain enlargement separated by over a million years of stasis.

We will only be able to make sense of the evidence, however, if we have some expectations about the types of minds that our ancestors may have possessed. Otherwise we will simply be faced with a bewildering mass of data, not knowing which aspects of it may be significant for our study. It is the task of Chapter 3 to begin to set up these expectations. I am able to do so because psychologists have realized that we can understand the modern mind only by understanding the process of evolution. Consequently while archaeologists have been developing a ‘cognitive archaeology’, psychologists have been developing an ‘evolutionary psychology’. These two new sub-disciplines are in great need of each other. Cognitive archaeology cannot develop unless archaeologists take note of current thinking within psychology; evolutionary psychologists will not succeed unless they pay attention to the behaviour of our human ancestors as reconstructed by archaeologists. It is my task within this book to perform a union, the offspring of which will be a more profound understanding of the mind than either archaeology or psychology alone can achieve.

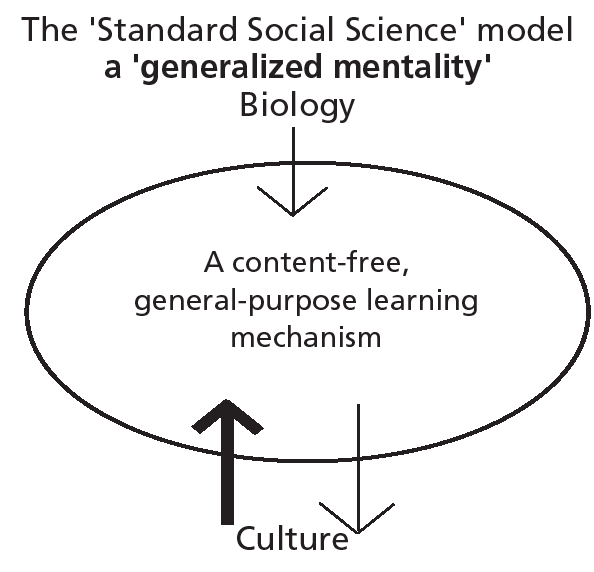

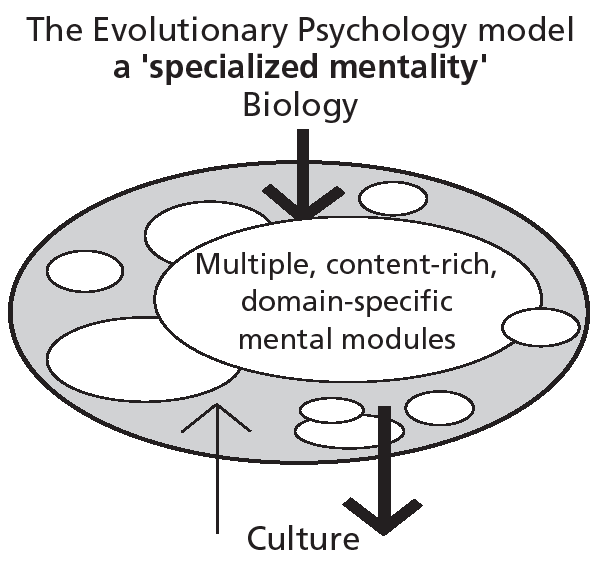

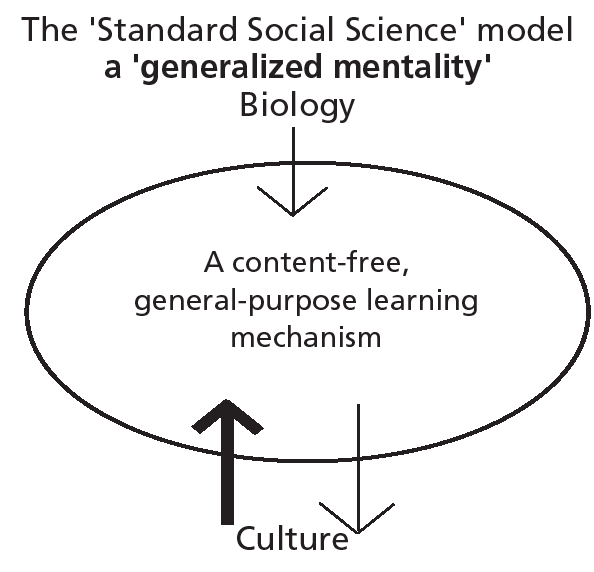

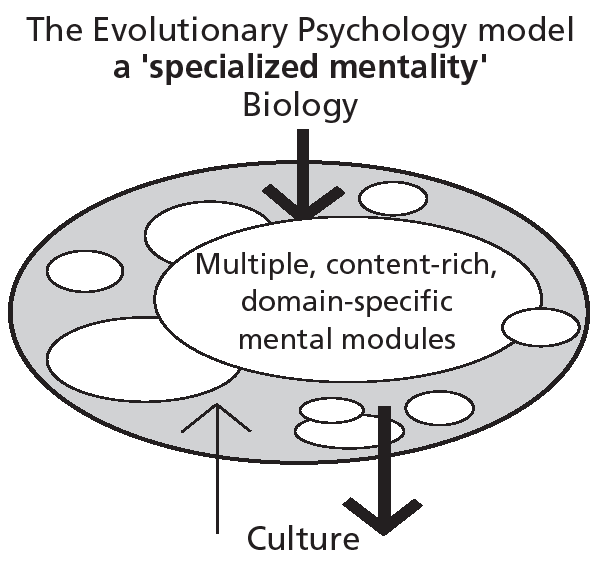

Chapter 3 will be concerned with outlining the developments in psychology that need to be brought into contact with the knowledge we have of past behaviour. One of the fundamental arguments of the new evolutionary psychology is that it is wrong to view the mind as a general-purpose learning mechanism, like some sort of powerful computer. This idea is dominant within the social sciences, and is indeed a ‘commonsense’ view of the mind. The evolutionary psychologists argue that we should replace it with a view of the mind as a series of specialized ‘modules’, or ‘cognitive domains’ or ‘intelligences’, each of which is dedicated to some specific type of behaviour7 (see Box p. 14) – such as modules for acquiring language, or tool-using abilities, or engaging in social interaction. As I will explain in the following chapters, this new view of the mind does indeed hold a key to unlocking the nature of both the prehistoric and modern mind – although in a very different way from that in which the evolutionary psychologists currently believe. The contrast between a ‘generalized’ and ‘specialized’ mentality will emerge as a critical theme throughout this book.

Two views of the mind

(after Cosmides & Tooby 1992)

|

|

| According to psychologists Leda Cosmides & John Tooby, social scientists tend to regard the mind as a content-free, general-purpose learning mechanism. At birth the mind is a 'blank slate' and our knowledge of the world and the manner in which we think is acquired from our culture. In this view of the mind, our biology plays a limited role in the nature of our minds. |

Evolutionary psychologists argue that our biological makeup has a major influence over the way we think. They believe that the mind is constituted by a series of specialized cognitive processes, each dedicated to a specific type of behaviour – like the blades of a Swiss army knife. At birth these already contain a substantial amount of knowledge about the world. |

As we look at the new ideas of evolutionary psychology, we will find another dilemma that requires resolution. If the mind is indeed constituted by numerous specialized processes each dedicated to a specific type of behaviour, how can we possibly account for one of the most remarkable features of the modern mind: a capacity for an almost unlimited imagination? How can this arise from a series of isolated cognitive processes each dedicated to a specific type of behaviour? The answer to this dilemma can only be found by exposing the prehistory of the mind.

In Chapter 4 I will draw upon the ideas of evolutionary psychology, supplemented by ideas from other fields, such as child development and social anthropology, to suggest an evolutionary scenario for the mind. This will provide the template for the reconstruction of prehistoric minds in the following chapters. In Chapter 5 we will begin that task by tackling the mind of the common ancestor to apes and humans who lived 6 million years ago. We have no fossil traces or archaeological remains of that ancestor and will consequently make an assumption that the mind of this ancestor was not fundamentally different from that of the chimpanzee today. We will ask questions such as what do the tool-using and foraging abilities of chimpanzees tell us about the chimpanzee mind – and hopefully that of the 6-million-year-old common ancestor?

In the next two chapters we will reconstruct the minds of our human ancestors prior to the appearance of Homo sapiens sapiens – our own species – in the fossil record 100,000 years ago. In Chapter 6 we will focus on the first member of the Homo lineage, Homo habilis. As well as being the first identifiable ancestor to make stone tools, Homo habilis was also the first to have a diet with a relatively large quantity of meat. What do these new types of behaviour tell us about the Homo habilis mind? Did Homo habilis have a capacity for language? Did this species possess a conscious awareness about the world similar to ours today?

In Chapter 7 we will look at a group of human ancestors and relatives whom I will refer to as the ‘Early Humans’. The best known of these are Homo erectus and the Neanderthals. The Early Humans existed between 1.8 million years ago and a mere 30,000 years ago. It will be when reconstructing the Early Human mind that we face the problem of explaining what the new brain processing power that appeared after 500,000 years ago was doing, given that we see limited change in Early Human behaviour during this period – which is why we can group all these ancestors together as Early Humans.

The Neanderthals provide us with our greatest challenge, a challenge I take up when I ask in Chapter 8 what it may have been like to have the mind of a Neanderthal. Popularly thought to be rather lacking in intelligence, we will see how in many ways Neanderthals were very similar to us, such as in terms of their brain size and their level of technical skill as evident from their stone tools. Yet in other ways they were very different, such as in their lack of art, ritual and tools made from anything but stone and wood. This apparent contradiction in Neanderthal behaviour – so modern in some ways, so primitive in others – provides vital evidence for reconstructing the nature of the Neanderthal mind. By doing so we will gain a clue as to the fundamental feature of the modern mind – a clue that remains hidden from psychologists, philosophers and indeed any scientist who ignores the evidence from prehistory.

The climax of our enquiry then comes with Chapter 9, ‘The big bang of human culture’. We will see that when the first modern humans, Homo sapiens sapiens, appeared 100,000 years ago they seem to have behaved in essentially the same manner as Early Humans, such as Neanderthals. And then, between 60,000 and 30,000 years ago – with no apparent change in brain size, shape or anatomy in general – the cultural explosion occurred. This resulted in such a fundamental change in lifestyles that there can be little doubt that it derived from a major change in the nature of the mind. I will argue that this change was nothing less than the emergence of the modern mind – the same mentality that you and I possess today. Chapter 9 will be concerned with describing the new mentality, while Chapter 10 will then suggest how it arose.

In Chapter 11, my final chapter, I will move from considering the prehistory of the mind, to the evolution of the mind. Whereas the course of the book tracks how the mind has changed during the last 6 million years, in that final chapter I will adopt a truly long-term perspective by beginning 65 million years ago with the very first primates. By doing so we will be able to appreciate how the modern mind is the product of a long, slow evolutionary process – although a process that has a remarkable and hitherto unrecognized pattern.

I complete my book with an epilogue which addresses the origins of agriculture 10,000 years ago. This event transformed human lifestyles and created new developmental contexts for young minds – contexts within sedentary farming societies rather than a mobile hunting and gathering existence. Yet I will show in the course of this book that the most fundamental events which defined the nature of the modern mind occurred much earlier in prehistory. The origins of agriculture are indeed no more than an epilogue to the prehistory of the mind.

In this book I intend to specify the ‘whats’, ‘whens’ and ‘whys’ for the evolution of the mind. While following its course I will be searching for – and will find – the cognitive foundations of art, religion and science. By exposing these foundations it will become clear how we share common roots with other species – even though the mind of our closest living relative, the chimpanzee, is indeed so fundamentally different from our own. I will thus provide the hard evidence to reject the creationist claim that the mind is a product of supernatural intervention. At the end of this prehistory I hope I will have furthered an understanding of how the mind works. And I also hope to have demonstrated why one should ask an archaeologist about the human mind.