11 The evolution of the mind

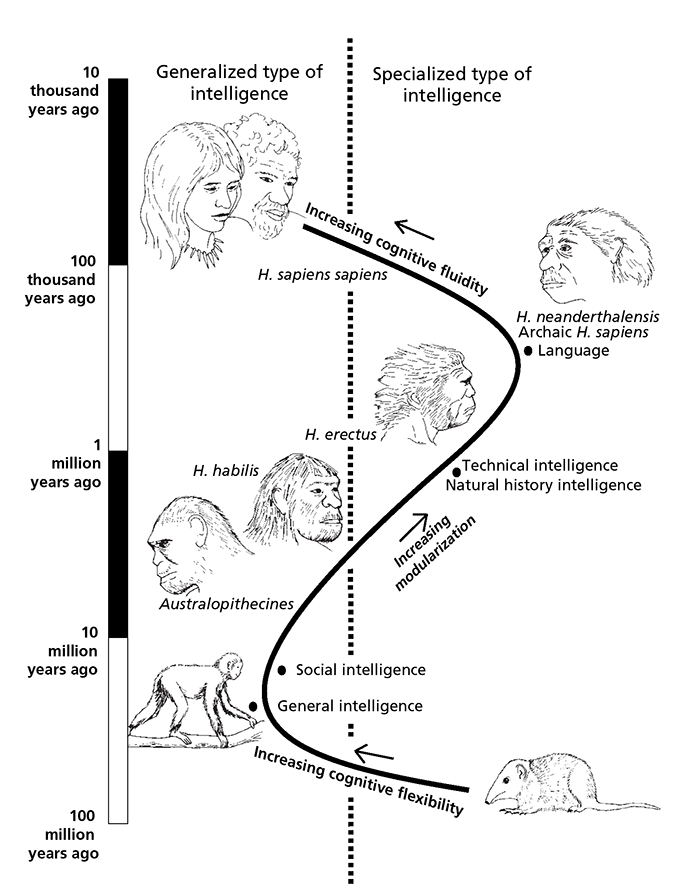

THE CRITICAL STEP in the evolution of the modern mind was the switch from a mind designed like a Swiss army knife to one with cognitive fluidity, from a specialized to a generalized type of mentality. This enabled people to design complex tools, to create art and believe in religious ideologies. Moreover, as I argue in the Boxes on pp. 196‒97 and 198, the potential for other types of thought which are critical to the modern world can be laid at the door of cognitive fluidity. So too can the rise of agriculture as I will explain in the Epilogue to this book – for agriculture and its consequences do indeed constitute the cultural epilogue to the evolution of the mind.

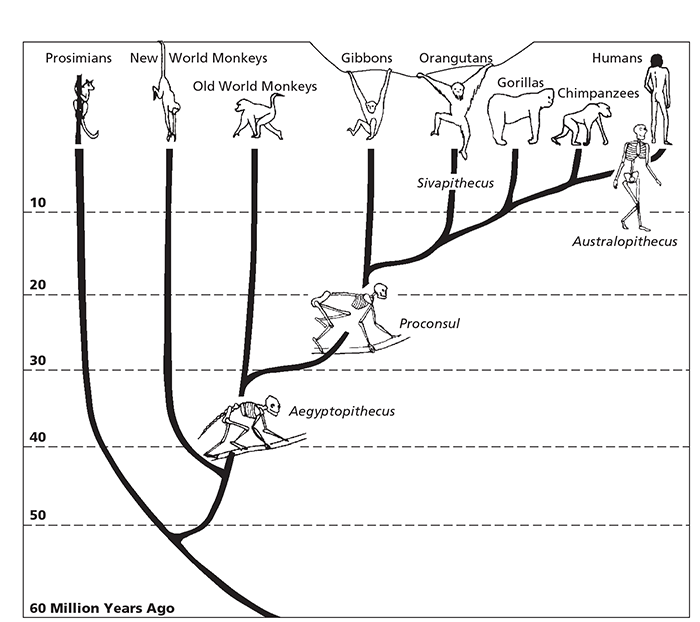

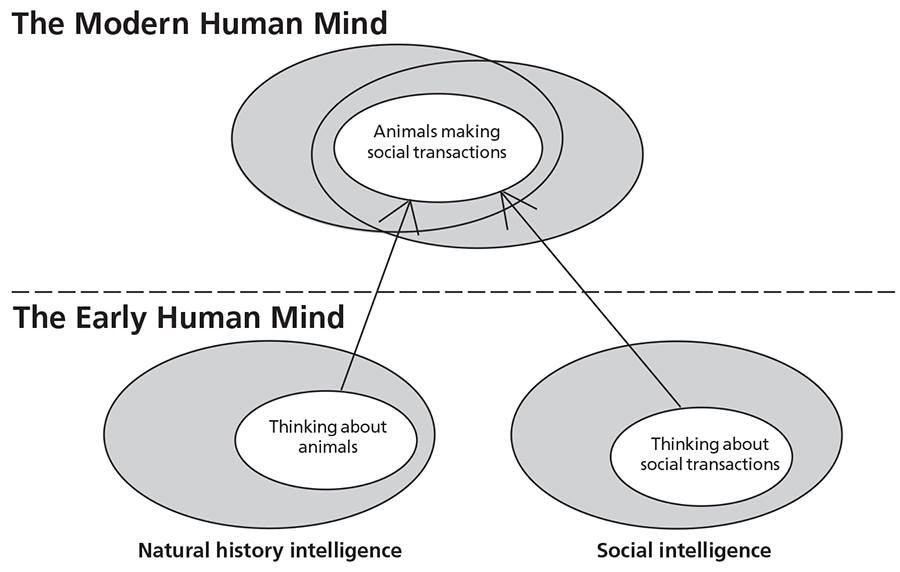

The switch from a specialized to a generalized type of mentality between 100,000 and 30,000 years ago was a remarkable ‘about turn’ for evolution to have taken. The previous 6 million years of evolution had seen an ever-increasing specialization of the mind. Natural history, technical and then linguistic intelligence had been added to the social intelligence that was already present in the mind of the common ancestor to living apes and humans. But what is even more remarkable is that this recent switch from specialized to generalized ways of thinking was not the only ‘about turn’ that occurred during the evolution of the modern mind. If we chart the evolution of the mind not just over the mere 6 million years of this prehistory, but over the 65 million years of primate evolution, we can see that there has been an oscillation between specialized and generalized ways of thinking.

In this final chapter I want to put the modern mind in its truly long-term context by charting and explaining this long-term oscillation in the nature of the mind. Only by doing so can we appreciate how we are products of a long, slow gradual process of evolution and how we differ so much from our closest living relative, the chimpanzee. And in doing so I want firmly to embed the evolution of the mind into that of the brain, and indeed the body in general. I must begin by introducing some rather shadowy new actors who now appear in a long prologue to the play that is our past (see Figure 28).1

Sixty-five million years of the mind

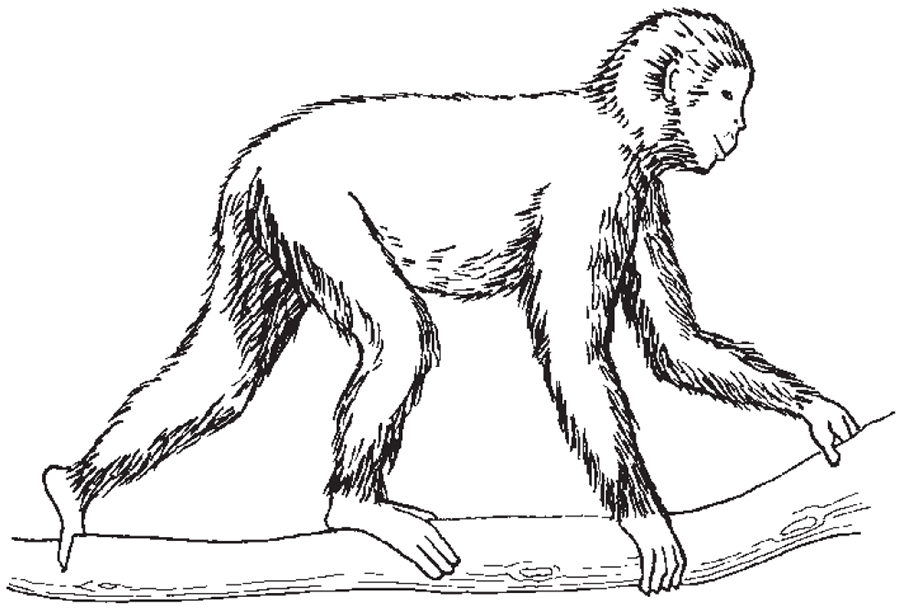

We must start 65 million years ago with a creature known as Purgatorius, represented by sparse cranial and dental fragments coming from eastern Montana, USA. This animal was a member of a group known as the plesiadapiforms. Purgatorius appears to have been a mouse-sized creature which lived on insects. The best preserved of its group was known as Plesiadapis: about the size of a squirrel, it fed on leaves and fruit (see Figure 29).

Racist attitudes as a product of cognitive fluidity

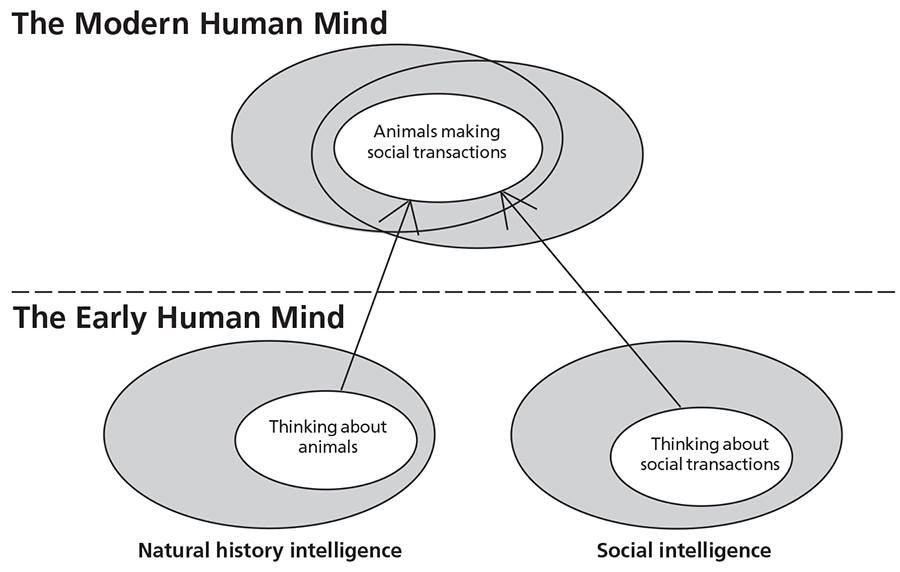

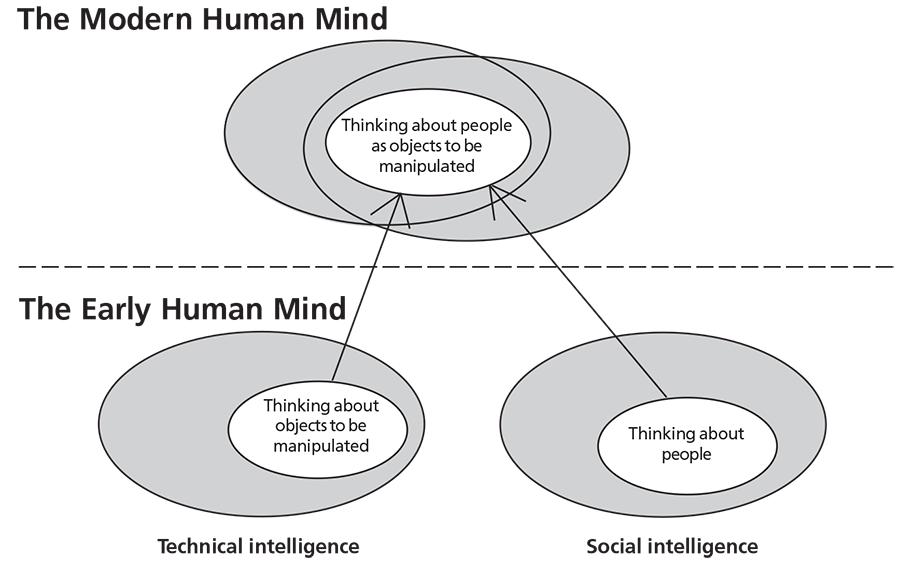

In Chapter 9 I argued that cognitive fluidity led to anthropomorphic and totemic thinking, since the accessibility between the domains of natural history and social intelligence meant that people could be thought of as animals, and animals could be thought of as people. The consequences of an integration of technical and social intelligence are more serious. Technical intelligence had been devoted to thought about physical objects, which have no emotions or rights because they have no minds. Physical objects can be manipulated at will for whatever purpose one desires. Cognitive fluidity creates the possibility that people will be thought of in the same manner.

We are all aware of such racist attitudes in the modern world, typified in the treatment of racial minorities. The roots of denying people their humanity would appear to stretch back to the dawn of the Upper Palaeolithic. Perhaps this is indeed what we see with the burial of part of a polished human femur with one of the children at Sungir 28,000 years ago and the defleshing of human corpses at Gough’s Cave in Somerset, England, 12,500 years ago, which were discarded in the same manner as animal carcasses. Early Humans, with their Swiss-army-knife-like mentality, could not think of other humans as either animals or artifacts. Their societies would not have suffered from racist attitudes. For Neanderthals, people were people, were people. Of course those early societies could not have been peaceful Gardens of Eden with no conflict between individuals and groups. The idea that our ancestors may have lived in an idyllic state of cooperation and harmony was shown to be nonsense as soon as Jane Goodall, in her 1990 book Through a Window about the chimpanzees of Gombe, described how she saw bloodthirsty brutal murder and cannibalism of one chimpanzee by another. There can be little doubt that Early Humans engaged in similar conflicts as they attempted to secure and maintain power within their groups, and access to resources. But what Early Humans may have lacked were beliefs that other individuals or groups had different types of mind from their own – the idea that other people are ‘less than human’ which lies at the heart of racism.

The social anthropologists Scott Atran and Pascal Boyer have both independently suggested that the idea that there are different human races comes from a transfer into the social sphere of the concept of ‘essences’ for living things that, as we saw in Chapter 3, is a critical part of intuitive biology. This transfer appears to happen spontaneously in the minds of young children. As another social anthropologist, Ruth Benedict, made clear in her classic 1942 study entitled Race and Racism, believing that differences exist between human groups is very different from believing that some groups are inherently inferior to others. For this view, which we can call racism, we seem to be looking at the transfer into the social sphere of concepts about manipulating objects, which indeed do not mind how they are treated because they have no minds at all. My argument here is that the cognitive fluidity of the Modern Human mind provides a potential not only to believe that different races of humans exist, but that some of these may be inferior to others due to the mixing up of thoughts about humans, animals and objects. There is no compulsion to do this, simply the potential for it to happen. And unfortunately that potential has been repeatedly realized throughout the course of human history.

It is unclear whether or not the plesiadapiforms should be classified as primates. They lack characteristic primate features in certain regions of their skulls and in their mode of locomotion, as far as these can be reconstructed from fragmentary fossil remains. It is in fact possible that rather than being primates, the plesiadapiforms shared a common ancestor with the earliest true primates which appeared after 55 million years ago. In view of this uncertain evolutionary status, plesiadapiforms are best described as ‘archaic primates’.

Our concern is with the type of mind that should be attributed to these creatures. It would seem appropriate to characterize their pattern of behaviour as more directly under the control of genetic mechanisms than of learning. A strict division between these – between ‘nature’ and ‘nurture’ – has long been rejected by scientists. Any behaviour must be partly influenced by the genetic make-up of the animal and partly by the environment of development. Nevertheless, the relative weighting of these varies markedly between species, and indeed between different aspects of behaviour within a single species.

Humour as a product of cognitive fluidity

Here is a joke:

A kangaroo walked into a bar and asked for a scotch and soda. The barman looked at him a bit curiously and then fixed the drink. ‘That will be two pounds fifty’ said the barman. The kangaroo pulled out a purse from his pouch, took out the money and paid. The barman went about his business for a while, glancing from time to time at the kangaroo, who stood sipping his drink. After about five minutes the barman went over to the kangaroo and said, ‘You know, we don’t get many kangaroos in here.’ The kangaroo replied, ‘At two pounds fifty a drink, it’s no wonder.’

This joke was quoted by Elliot Oring in his 1992 book Jokes and their Relations to illustrate what he believes to be a fundamental feature of successful humour: ‘appropriate incongruities’. In this joke there are lots of incongruities: kangaroos walking into bars, speaking English and drinking scotch. But the response of the kangaroo to the barman’s remark is an ‘appropriate incongruity’ due to the way the barman framed his remark. This implied that there were scotch-drinking, English-speaking kangaroos around, but that they simply were not visiting his particular bar.

It is readily evident that the potential to entertain ideas that bring together elements from normally incongruous domains arises only with a cognitively fluid mind. Had Neanderthals known about kangaroos, scotch and bars, they could not have thought of the incongruous situation of kangaroos buying a drink because their knowledge about social transactions would have been in one cognitive domain and that about kangaroos in another. And consequently their Swiss-army-knife mentality may have denied them what seems to be an essential element of a sense of humour.

It is useful here briefly to consider some findings from laboratory studies on the learning capacities of different types of animals. These studies require animals to solve problems, such as about getting food by pressing the correct levers, and have shown that primates as a whole have a greater capacity for learning than other animals, such as rats, cats and pigeons. By ‘learning’, I am referring here to what I have called throughout this book ‘general intelligence’ – a suite of general-purpose learning rules, such as those for learning associations between events. Only primates appear able to identify general rules that apply in a set of experiments, and to use the general rule when faced with a new problem to solve. While rats and cats can solve simple problems, they do not show any improvement over a series of learning tasks.2

28 A simplified chart of human evolution.

29 Plesiadapis.

Returning to the plesiadapiforms, and remembering that they may not be primates at all, it would seem likely that they would fall in with the rats and the cats on such tasks, rather than with the primates. In other words, we should attribute them with a minimal general intelligence, if one at all. The lives of the plesiadapiforms were probably dominated by relatively innately specified behaviour patterns, that arose as a response to specific stimuli and which were hardly modified at all by experience. We could indeed think of the plesiadapiform mind/brain as being constituted by a series of modules, encoding highly specialized knowledge about patterns of behaviour. To put it in other words, they possessed a type of Swiss-army-knife mentality.

The plesiadapiforms declined in abundance around 50 million years ago. This coincided with a proliferation of rodents, which probably out-competed the plesiadapiforms for leaves and fruit. However, by around 56 million years ago two new primate groups had appeared, referred to as the omomyids and the adapids. These are the first ‘modern primates’ and looked similar to the lemurs, lorises and the tarsier of today. These first modern primates were agile tree dwellers, specialized for eating fruit and leaves. The best preserved is Notharctus, whose fossil remains come from North America (see Figure 30).

The most notable feature of these early primates is that they were the first to possess a relatively large brain. By this I mean that they had a brain size larger than what one would expect on the basis of their body size alone when compared with other mammals of their time period.3 In general, larger animals need larger brains, simply because they have more muscles to move and coordinate. Primates as a group, however, have brains larger than would be predicted by their body size alone. The evolution of this particularly large brain size is described as the process of encephalization – and we can see that it began with these early primates of 56 million years ago.

I referred to this group at the end of Chapter 5 when we were considering the evolution of social intelligence. As I noted, if their minds were similar to those of lemurs today, it is unlikely that they possessed a specialized social intelligence. It is probable, however, that they possessed a ‘general intelligence’, supplementing the modules for relatively innately specified behaviour patterns. The biological anthropologist Katherine Milton has argued that the selective pressure for this general intelligence was the spatial and temporal ‘patchiness’ of the arboreal plant resources they were exploiting. Simple learning rules allowed primates to lower the food acquisition costs and improve foraging returns.4 Yet general intelligence may also have had benefits in other domains of behaviour, such as by facilitating the recognition of kin.

30 Notharctus.

It is at this date, therefore, of about 56 million years ago, that we have the first ‘about turn’ in the evolution of the mind. We can see a switch from a specialized type of mentality possessed by archaic primates, with behavioural responses to stimuli largely hard-wired into the brain, to a generalized type of mentality in which cognitive mechanisms allow learning from experience. Evolution appears to have exhausted the possibilities for increasing hard-wired behavioural routines: an alternative evolutionary path was begun of generalized intelligence.

General intelligence required a larger brain to allow the information processing required to make simple cost/benefit calculations when choosing between behavioural strategies, and to enable knowledge to be acquired by associative learning. For a larger brain to have evolved, these early modern primates would have needed to exploit high-quality plant foods such as new leaves, ripe fruits and flowers – as is confirmed by their dental features. Such dietary preferences were essential in order to permit a reduction in gut size and consequently the release of sufficient metabolic energy to fuel the enlarged brain while maintaining a constant metabolic rate.5

The next important group of primates come from Africa, notably the sedimentary deposits of the Fayum depression in Egypt. The most important of these is Aegyptopithecus, which lived around 35 million years ago. This was a fruit-eating primate, living in the tall trees of monsoonal rainforests. Its body appears to have been adapted for both climbing and leaping. Like all the previous primates, it was a quadruped committed to moving on all four limbs. The most important primate fossils from the period 23–15 million years ago are likely to represent several species, but are referred to as Proconsul. These fossils are found in Kenya and Uganda, and show both monkey-like and ape-like features (see Figure 31).

The mind of Aegyptopithecus probably differed from that of Notharctus and the other early modern primates in two major respects. First the domain of general intelligence became more powerful – giving greater information processing power. The second change is of more significance: the evolution of a specialized domain of social intelligence.

If we follow the scenario put forward by Dick Byrne and Andrew Whiten, by 35 million years ago there was a form of social intelligence which resulted in significantly more complex behaviour in the social domain than in the interaction with the non-social world – as I discussed in Chapter 5. This domain of social intelligence evolved thanks to the reproductive advantage it gave individuals in terms of being able to predict and manipulate the behaviour of other members of the group. As argued by Leda Cosmides and John Tooby, those individuals with a suite of specialized mental modules for social intelligence are likely to have had more success at solving the problems of the social world. In other words, by 35 million years ago evolution seems to have exhausted the possibilities of improving reproductive success by enhancing general intelligence alone: an evolutionary turn around was made which began an ever-increasing specialization of mental faculties that continued until almost the present day.

31 Proconsul.

It is during this period that Andrew Whiten’s characterization of brain evolution as deriving from a ‘spiralling pressure as clever individuals relentlessly selected for yet more cleverness in their companions’ is appropriate.6 As Nicholas Humphrey has described, when intellectual prowess is correlated with social success, and if social success means high biological fitness, then any heritable trait which increases the ability of an individual to outwit his fellows will soon spread through the gene pool.7

This ‘spiralling pressure’ probably continued in the period between 15 and 4.5 million years ago, during which the fossil record is particularly sparse.8 It was in this time period, at around 6 million years ago, that the common ancestor of modern apes and humans lived, and it was with this missing actor that I began the play of our past. Byrne and Whiten suggest that by the time of the common ancestor, social intelligence had become sufficiently elaborated to involve abilities at attributing intentions to other individuals and to imagining other possible social worlds.

When the fossil record improves after 4.5 million years ago, the australopithecines are established in East Africa and possibly elsewhere in that continent. As we saw in Chapter 2, the best preserved of these, A. afarensis, displays adaptations for a joint arboreal and terrestrial lifestyle. As can be seen in Figure 1, the fossils between 3.5 and 2.5 million years ago suggest that this was a period of stability with regard to brain size. Why should the ‘spiralling pressure’ for ever greater social intelligence, and consequently brain expansion, have come to an end – or at least a hiatus? The probable answer is that evolution now confronted two severe constraints: bigger brains need more fuel, and bigger brains need to be kept cool. With regard to fuel, brains are very greedy, requiring over 22 times more energy than muscle tissue while at rest. With regard to temperature, an increase of only 2°C (3.6°F) can lead to impaired functioning of the brain.9

The australopithecines are likely to have been mainly vegetarian and lived in the equatorial, wooded savannahs. This lifestyle constrained the amount of energy that could be supplied to the brain, and exposed them to constant risk of over heating. Brain expansion could therefore not have occurred, even if the selective pressures for it had been present.

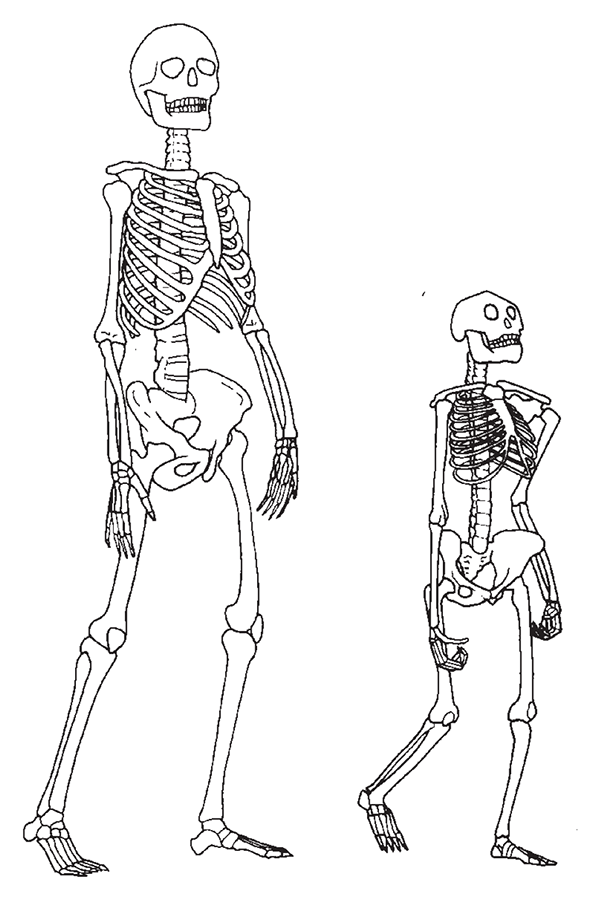

Had it not been for a remarkable conjunction of circumstances, it is likely that australopithecines would still be foraging in Africa and that the Homo lineage would not have evolved. But as we saw in Figure 1, at around 2 million years ago there started a very rapid period of brain expansion, marking the appearance of the Homo lineage. This could only have arisen if the constraints on brain expansion had been relaxed – and of course if selective pressures were present. When trying to explain how this happened, the inter relationships between the evolution of the mind, the brain and the body become of paramount importance. There are two behavioural developments in this period which are of critical importance: bipedalism – habitual walking on two legs – and increased meat eating.

The evolution of bipedalism had begun by 3.5 million years ago. Evidence for this is found in the anatomy of A. afarensis (see Figure 32), and, more dramatically, by the line of australopithecine footprints preserved at Laetoli in Tanzania. The most likely selective pressure causing the evolution of bipedalism was the thermal stress suffered by the australopithecines when foraging in the wooded savannahs of East Africa. With their tree-climbing and tree-swinging ancestry, the australopithecines had a body already conditioned for an upright posture. The anthropologist Peter Wheeler has shown that by adopting bipedalism australopithecines could achieve a 60 percent reduction in the amount of solar radiation they experienced when the sun was over head. Moreover, the energetic costs of locomotion would have been reduced. Bipedalism enabled australopithecines to forage for longer periods without the need for food and water, to forage in environments which had less natural shade, and thus to exploit foraging niches not open to other predators who were more heavily tied to sources of shade and water.10 The shift to increasingly efficient bipedalism may have been partly related to the environmental change to more arid and open environments that occurred in Africa at around 2.8 million years ago,11 increasing the value of reducing exposure to solar radiation by adopting an upright posture.

Bipedalism required a larger brain for the muscle control needed for balance and locomotion. But bipedalism and a terrestrial lifestyle had several other consequences for brain enlargement. Some of these have been discussed by the anthropologist Dean Falk.12 She explains how a new network of veins covering the brain must have been jointly selected for with bipedalism to provide a cooling system for the brain – or a ‘radiator’ as she describes it. Once in place, the constraint of over heating on further expansion of the brain was relaxed as this radiator could easily be modified. Consequently the possibility (not necessity) arose of further brain enlargement.

32 A comparison of the size and posture of ‘Lucy’ (right) – A. afarensis – and a Modern Human female (left). Lucy was about 105 cm (3 ft 5 in) tall, with notably long arms.

Dean Falk also suggests that bipedalism would have led to a reorganization of the neurological connections within the brain: ‘once feet had become weight bearers (for walking) instead of graspers (a second pair of hands) areas of cortex previously used for foot control were reduced thus freeing up cortex for other functions’.13 This of course went with the ‘freeing’ of the hands, providing opportunities for enhanced manual dexterity for carrying and toolmaking. There may also have been significant changes in the perception of the natural environment due to an increase in the distances and directions regularly scanned; and a change in the social environment by an increase in face-to-face contact, enhancing the possibilities for communication by facial expression.

Perhaps the most significant consequence of bipedalism, however, is that it facilitated the exploitation of a scavenging niche. A ‘window of opportunity’ was opened to exploit carcasses during periods of the day when carnivores needed to find shade. As Leslie Aiello and Peter Wheeler have discussed, with an increasing amount of meat in the diet, the size of the gut could be further reduced, releasing more metabolic energy to the brain while maintaining a constant basal metabolic rate.14 And in this way a further constraint on the enlargement of the brain was relaxed.

The main selective pressures for brain enlargement no doubt continued to come from the social environment: the spiralling pressures caused by socially clever individuals creating the selective pressure for even more social intelligence in their companions. And this pressure itself was present due to the need for large social groups that a terrestrial lifestyle in open habitats required, partly as a defence against predators.

Confirmation of the importance of the social environment for the expansion of brain size was found in Chapter 6. As we saw in that chapter, it is clear that the Oldowan stone tools of early Homo demanded more knowledge to make than those which chimpanzees use today, and therefore those likely to have been used by the australopithecines. But this knowledge probably arose from the enhanced opportunities for social learning in larger groups rather than as a consequence of selection for a domain of technical intelligence. Similarly, the narrow range of environments exploited by early Homo suggests that a discrete domain of natural history intelligence had not yet evolved and that the information requirements for scavenging were also being met as a by-product of living in larger social groups.

In my reconstruction of the evolution of the mind I only found the first evidence for distinct domains of natural history and technical intelligence at 1.8–1.4 million years ago with the appearance of H. erectus, and the technically demanding handaxes. What were the causes, conditions and consequences for these new domains of intelligence?

The ultimate cause for these new specialized intelligences was the continuing competition between individuals – the cognitive arms race that had been unleashed when the constraints on brain enlargement had been relaxed. But the evolution of these specific intellectual domains may well reflect the appearance of a constraint on any further enhancement of social intelligence itself. As Nicholas Humphrey noted, ‘there must surely come a point when the time required to solve a social argument becomes insupportable’.15 So, just as the possibilities of increasing reproductive success by enhancing general intelligence alone by natural selection had been exhausted by 35 million years ago, we might also conclude that the ‘path of least resistance’ for a further evolution of the mind in the conditions existing at 2 million years ago lay not in enhanced social intelligence but in the evolution of new cognitive domains: natural history and technical intelligence.

In other words, those individuals gaining most reproductive success were the ones who were most efficient at finding carcasses (and other food resources) and most able to butcher them. These individuals gained a better quality of diet, and spent less time exposed to predators on the savannah. As a result, they enjoyed a better state of health, could compete more successfully for mates, and produced stronger offspring. With regard to toolmaking, behavioural advantage was gained by those individuals who were able to have ready access to suitable raw materials for removing meat and breaking open bones of a carcass. The advantages of artifacts such as handaxes may well have been that they could be carried as raw material for flakes, as well as used as a butchering tool themselves. Experimental studies have repeatedly shown that they are very effective general-purpose tools.

Bipedalism, the scavenging niche, the existence of raw materials, the competition from other carnivores – these were all conditions that enabled the enhanced intellectual abilities at toolmaking and natural history to be selected for. Had one of these conditions been missing, we might still be living on the savannah.

The most significant behavioural consequence of these new cognitive domains was the colonization of large parts of the Old World. The evolution of a natural history and technical intelligence thus opened up a further window of opportunity for human behaviour. Within less than 1.5 million years, our recent relatives were living as far apart as Pontnewydd Cave in north Wales, the Cape of South Africa and the tip of Southeast Asia. There could be no more effective demonstration that the Swiss-army-knife mentality of Early Humans provided a remarkably effective adaptation to the Pleistocene world. Indeed, there appears to have been no further brain enlargement and no significant changes in the nature of the mind between 1.8 and 500,000 years ago.

This is not to argue that all minds were exactly the same; the H. erectus and H. heidelbergensis populations that dispersed throughout much of the Old World were living in diverse environments, resulting in subtle differences in the nature of their multiple intelligences. An example I gave in Chapter 7 referred to juveniles living in relatively small social groups in wooded environments during inter glacial periods who will have had less opportunity to observe toolmaking, and whose minds consequently will not have developed the technical skills found in other Early Human populations.

The fourth cognitive domain to have evolved in the Early Human mind was that of language. It is likely that as far back as 2 million years ago, selective pressures existed for enhanced vocalizations. In this book I have followed Robin Dunbar’s and Leslie Aiello’s arguments that language initially evolved as a means of communicating social information alone rather than information about subjects such as tools or hunting. As group sizes enlarged, mainly due to the pressures of a terrestrial lifestyle, those individuals who could reduce the time they needed to spend in building social ties by grooming – or who acquired greater amounts of social knowledge with the same time investment – were reproductively more successful.

Just as the tree-living ancestry of the australopithecines enabled bipedalism to evolve, so too did bipedalism itself make possible the evolution of an enhanced vocalization capacity among early Homo, and particularly H. erectus. This has been made clear by Leslie Aiello.16 She has explained how the upright posture of bipedalism resulted in the descent of the larynx, which lies much lower in the throat than in the apes. A spin off, not a cause, of the new position of the larynx was a greater capacity to form the sounds of vowels and consonants. In addition, changes in the pattern of breathing associated with bipedalism will have improved the quality of sound. Increased meat eating also had an important linguistic spin off, since the size of teeth could be reduced thanks to the greater ease of chewing meat and fat, rather than large quantities of dry plant material. This reduction changed the geometry of the jaw, enabling muscles to develop which could make the fine movements of the tongue within the oral cavity necessary for the diverse and high-quality range of sounds required by language.

The linguistic capacity was intimately connected with the domain of social intelligence within the Early Human mind. But technical and natural history intelligence remained isolated from these, and from each other. As I discussed in Chapter 7, this created the distinctive characteristics of the Early Human archaeological record, appearing very modern in some respects, but very archaic in others.

As I explained at the end of Chapter 7, while H. erectus probably possessed a capacity for vocalizing substantially more complex than what we see in apes today, it is likely to have remained relatively simple compared with human language. The evolution of the two principal defining features of language, a vast lexicon and a set of grammatical rules, seems to be related to the second spurt of brain enlargement that happened between 500,000 and 200,000 years ago. Yet even with these elements present, it remained in essence a social language. Explanations for this second period of brain enlargement are less easy to propose than for the initial spurt, which is clearly related to the origin of bipedalism and a terrestrial lifestyle.

One possibility is that the renewed brain enlargement relates to a further expansion of the size of social groups, resulting in those individuals with enhanced linguistic capacities being at a selective advantage. But the need for large group size is unclear – even remembering that this refers to the wider ‘cognitive group’, not necessarily the narrower group within which one lives on a day-to-day basis. Aiello and Dunbar suggest that it may simply reflect the increase in global human population and the need for defence not against carnivores, but other human groups.17

Yet here again another new window of opportunity arose for evolution. As soon as language acted as a vehicle for delivering information into the mind (whether one’s own or that of another person), carrying with it snippets of non-social information, a transformation in the nature of the mind began. As I suggested in Chapter 10, language switched from a social to a general-purpose function, consciousness from a means to predict other individuals’ behaviour to managing a mental data base of information relating to all domains of behaviour. A cognitive fluidity arose within the mind, reflecting new connections rather than new processing power. And consequently this mental transformation occurred with no increase in brain size. It was, in essence, the origins of the symbolic capacity that is unique to the human mind with the manifold consequences for hunter-gatherer behaviour that I described in Chapter 9. And, as we can now see, this switch from a specialized to a generalized type of mentality was the last in a set of oscillations that stretches back to the very first primates.

As I discussed in Chapter 10, one of the strongest selective pressures for this cognitive fluidity is likely to have been the provisioning of females with food. The expansion of the brain had resulted in an extension of infant dependency which increased the expenditure of energy by females and made it difficult for them to supply themselves with food. Consequently male provisioning is likely to have been essential, resulting in a need for connections between natural history and social intelligence. It is perhaps not surprising, therefore, that these cognitive domains appear to have been the first two to have become integrated – as is apparent from the behaviour of the Early Modern Humans of the Near East – to be followed some what later by technical intelligence. Moreover, the prolonged period of infancy provided the time for cognitive fluidity to develop.

This transition to a cognitively fluid mind was neither inevitable nor pre-planned. Evolution simply capitalized on a window of opportunity that it had blindly created by producing a mind with multiple specialized intelligences. It may be the case that by 100,000 years ago the mind had reached a limit in terms of specialization. It might be asked why cognitive fluidity did not evolve in the other types of Early Humans, the Neanderthals, or the archaic H. sapiens of Asia. Well, there may indeed be a trace of cognitive fluidity between social and technical intelligence in the very latest Neanderthals in Europe, as they seem to start making artifacts whose form is restricted in time and space, and consequently may be carrying social information.18 Yet before this could develop fully, they were pushed into extinction by the incoming Modern Humans, who had already achieved full cognitive fluidity.

Cognitive fluidity enabled people to engage in new types of activities, such as art and religion. As soon as these arose the developmental contexts for young minds began to change. Children were born into a world where art and religious ideology already existed; in which tools were designed for specific tasks, and where all items of material culture were imbued with social information. At 10,000 years ago the developmental contexts began to change even more fundamentally with the origins of an agricultural way of life, which, as I will explain in my Epilogue, is a further product of cognitive fluidity. As I described in Chapter 3, with these new cultural contexts, the hard-wired intuitive knowledge within the minds of growing infants may have ‘kick-started’ new types of specialized cognitive domains. For instance, a young child growing up in an industrial setting may no longer have developed a ‘natural history intelligence’. Instead, in some contexts, a specialized domain for mathematics may have developed, kick-started by certain features of ‘intuitive physics’, even though no prehistoric hunter-gatherer had ever developed such a domain.

The hectic and ongoing pace of cultural evolution unleashed by the appearance of cognitive fluidity continues to change the developmental contexts of young minds, resulting in new types of domain-specific knowledge. But all minds develop a cognitive fluidity. This is the defining property of the modern mind.

Oscillations in the evolution of the mind

If we stand back from this 65 million years, we can see how the selective advantages during the evolution of the mind have oscillated from those individuals with specialized intelligence, in terms of hard-wired modules, up to 56 million years ago, to those with general intelligence up to 35 million years ago, and then back again to those with specialized intelligence in the form of cognitive domains up until 100,000 years ago.

33 The evolution of human intelligence.

The final phase of cognitive evolution involved a further switch back to a generalized type of cognition represented by cognitive fluidity.

In the light of this evolutionary trajectory, as illustrated in Figure 33, it is not surprising that the modern mind is so frequently compared with that of a chimpanzee. Both have a predominantly generalized type of mentality (although chimpanzees have a specialized, isolated social intelligence), and therefore both look superficially similar. When we look at chimpanzees and modern hunter-gatherers we see a very smooth fit in each case between their technology and subsistence tasks. Both are very adept at making ‘tools for the job’. Chimpanzees often behave in a similar way to humans, especially when they are taught and encouraged by humans to make tools, or paint pictures or use symbols. We are led to believe that the chimpanzee and the human mind are essentially the same: that of Modern Humans simply being more powerful because the brain is larger, resulting in a more complex use of tools and symbols. The evolution of the mind, as I have documented in the preceding pages, shows this to be a fallacy: the cognitive architecture of the chimpanzee mind and the modern mind is fundamentally different.

Yet this poses an important question. If the end point of cognitive evolution has been to produce a mind with a generalized type of mentality, superficially similar to the generalized type of mentality of the chimpanzee (excepting social intelligence) and the one we attribute to our early primate ancestors, then why did it bother to go through a phase of multiple, specialized intelligences which had limited integration? Why did natural selection not simply build on general intelligence, gradually making it more complex and powerful?

The answer is that a switch between specialized and generalized systems is the only way for a complex phenomenon to arise, whether it is a jet engine, a computer program or the human mind. Indeed my colleague Mark Lake believes that repeated switching from general-purpose to specialized designs is likely to be a feature of evolutionary processes in general.19 To explain it let me return to one of the first analogies for the mind that I used in this book: the mind as a computer. Actually, let me be more specific and characterize the mind as a piece of software, and natural selection as the computer programmer – the designer. Both are common analogies, but no more. The mind/brain is as much a chemical soup as a series of electronic circuits, and natural selection has no goal; it is in Richard Dawkins memorable phrase the ‘Blind Watchmaker’.20 Let us briefly consider how natural selection blindly wrote the computer programs of the mind.

How is a complex piece of software produced? There are three stages. First one must write an overall plan for the program, often in the form of a series of separate routines that are linked together. The aim of this stage is simply to get the program to ‘run’, for all the routines to work together. This is analogous to natural selection building the general intelligence of our early primate ancestors: no complexity but a smoothly functioning system. The next stage is to add the complexity to the program in a piecemeal fashion. A good programmer does not try to add the required complexity to a program as a whole and all at once: if this is attempted, de-bugging becomes impossible and the program repeatedly crashes. The faults cannot be located and they pervade the system.

The only way to move from a simple to a complex program is to take each routine in turn, and develop it on an independent basis to perform its own specialized and complex function, ensuring that it remains compatible with the initial program design. This is what natural selection under took with the mind; specialized intelligences were developed and tested separately, using general intelligence to keep the whole system running. Only when each routine has been developed on an independent basis does a programmer glue them back together in order simultaneously to perform their complex functions as an advanced computer program. This integration is the third and final stage of writing a complex program. Natural selection did it for the mind by using general-purpose language and consciousness as the glue. The result was the cultural explosion I described in Chapter 9.

In this regard, natural selection was simply being a very good (though blind) programmer when building the complex modern mind. If it had tried to evolve the complex, generalized type of modern mind directly from the simple, generalized type of mind of our early ancestors, without developing each cognitive domain in an independent fashion, it would simply have failed. Moreover, it is perhaps not surprising that we have found in this book a similar sequence of changes in the cognitive development of the child as in the cognitive evolution of the species.

The cognitive origins of science

Knowing the prehistory of the mind provides us with a more profound understanding of what it means to be human. I have used it to understand the origins of art and religion. And I must draw this book to a close by considering the third of the unique achievements of the modern mind, science, which I referred to in my introductory chapter, since this will lead us to identify the most important feature of our cognitively fluid minds.

Science is perhaps as hard to define as art or religion.21 But I believe there are three critical properties. The first is the ability to generate and test hypotheses. This is something which, as I argued in previous chapters, is fundamental to any specialized intelligence: chimpanzees are evidently generating and testing hypotheses about the behaviour of other individuals when they engage in deceptive behaviour by using their social intelligence. I argued that early Homo and Early Humans were needing to generate and test hypotheses about the distribution of resources, especially carcasses for scavenging, by using their natural history intelligence.

A second property of science is the development and use of tools to solve specific problems, such as a telescope to look at the moon, a microscope to look at a flea, or even a pencil and paper to record ideas and results. Now although the hunter-gatherers of the Upper Palaeolithic did not make telescopes and microscopes, they were nevertheless able to develop certain dedicated tools by being able to integrate their knowledge of natural history and toolmaking. Moreover, they were using material culture to record information in what the archaeologist Francesco D’Errico has described as ‘artificial memory systems’:22 the cave paintings and engraved ivory plaques of the Upper Palaeolithic are the precursors of our CD-Roms and computers. The potential to develop a scientific technology emerged with cognitive fluidity.

So too did the third feature of science. This is the use of metaphor and analogy, which are no less than the ‘tools of thought’.23 Some metaphors and analogies can be developed by drawing on knowledge within a single domain, but the most powerful ones are those which cross domain boundaries, such as by associating a living entity with something that is inert, or an idea with something that is tangible. By definition these can only arise within a cognitively fluid mind.

The use of metaphor pervades science.24 Many examples are widely known, such as the heart as a mechanical pump and atoms as miniature solar systems, while others are tucked away in scientific theories, such as the notion of ‘wormholes’ in relativity theory and ‘clouds’ of electrons in particle physics. Charles Darwin conceived of the world in metaphor ‘as a log with ten thousand wedges, representing species, tightly hammered in along its length. A new species can enter this crowded world only by insinuating itself into a crack and popping another wedge out.’25 The biologist Richard Dawkins is a master at choosing appropriate metaphors to explain evolutionary ideas, such as ‘selfish’ DNA, ‘natural selection as a blind watchmaker’ and ‘evolution as a flowing river’. Mathematicians are prone to talk about their equations and theorems using terms such as ‘well behaved’ and ‘beautiful’, as if they were living things rather than inert marks on pieces of paper.

The significance of metaphors for science has been discussed at length by philosophers, who recognize that they play a critical role not only in the transmission of ideas but in the practice of science itself. In his 1979 essay entitled ‘Metaphor in Science’, Thomas Kuhn explained that the role of metaphor in science goes far beyond that of a device for teaching and lies at the heart of how theories about the world are formulated.26 Much of science is perhaps similar to Daniel Dennett’s description of the study of human consciousness – a war of competing metaphors.27 Such a battle has indeed been fought in this book. If we could not think of the mind as a sponge, or a computer, or a Swiss army knife, or a cathedral, would we be able to think about and study the mind at all?

In summary, science like art and religion, is a product of cognitive fluidity. It relies on psychological processes which had originally evolved in specialized cognitive domains and only emerged when these processes could work together. Cognitive fluidity enabled technology to be developed which could solve problems and store information. Of perhaps even greater significance, it allowed the possibility for the use of powerful metaphors and analogy, without which science could not exist.

Indeed, if one should want to specify those attributes of the modern mind that distinguish it not only from the minds of our closest living relatives, the apes, but also our much closer, but extinct, ancestors, it would be the use of metaphor and what Jerry Fodor described as our passion for analogy. Chimpanzees cannot use metaphor and analogy, because with one single type of specialized intelligence, they lack the mental resources for metaphor, not to mention the language with which to express it. Early Humans could not use metaphor because they lacked cognitive fluidity. But for Modern Humans, analogy and metaphor pervade every aspect of our thought and lie at the heart of art, religion and science.

The human mind is a product of evolution, not supernatural creation. I have laid bare the evidence. I have specified the ‘whats’, the ‘whens’ and the ‘whys’ for the evolution of the mind. I have explained how the potential arose in the mind to undertake science, create art and believe in religious ideologies, even though there were no specific selection pressures for such abstract abilities at any point during our past. I have demonstrated that we can only understand the nature of language and consciousness by understanding the prehistory of the mind – by getting to grips with the details of the fossil and archaeological records. And I have found the use of metaphor and analogy in various guises to be the most significant feature of the human mind. I have myself only been able to think and write about prehistory and the mind by using two metaphors within this book: our past as a play and the mind as a cathedral.

It is perhaps fitting, therefore, that this last chapter has been largely written while staying in the Spanish city of Santiago de Compostela. This was one of the great centres of pilgrim age in the medieval world. The town has a remarkable collection of religious buildings which were built, and constantly modified, during the Middle Ages. These range from the simplicity of small churches with no more than a single nave to the complexity of the cathedral. Built on the site of a small ninth-century church, the cathedral is one of the masterpieces of Romanesque architecture. It has a three-aisled nave and no fewer than 20 chapels, each of which is dedicated to a different saint. The original Romanesque design has been modified by Gothic and later additions. My guide book to this cathedral and the other churches of Santiago tells me that walking within and between them will be like walking through history. But for me, it has been like walking through the Prehistory of the Mind.