5

Digital and Twenty-First-Century Skills

Introduction: who is able to deal with digital media?

Learning how to work with digital technology is a crucial step. Researchers in the early twenty-first century understood that skills and usage would become their primary focus, and Eszter Hargittai (2002) framed this research as the second-level digital divide.

This does not mean that, in the 1980s and 1990s, the operation and management of computers and Internet connections was believed to be unimportant. On the contrary, computers were not considered to be user-friendly machines. Indeed, in the 1960s and 1970s only experts and programmers were able to handle them. Even when the general population started to work with PCs in the 1990s, their operation was still thought to be more difficult than that of other media.

In the first decade of the twenty-first century the capacity to work effectively with digital media was extended with content-related skills, as people began working with sources of information and communication. Twenty-first-century skills are problem-solving and decision-making, critical thinking, creativity, and cooperating with peers or in teamwork.

The following section will deal with the various concepts of these skills. I will explain why I prefer the term skills rather than competencies, capabilities, literacies or other terms. The early twenty-first century was marked by numerous attempts to find a framework for digital skills, competencies or literacies. I shall explain some of these frameworks and discuss the similarities and differences between digital skills and traditional media skills or literacies. Finally, I will ask whether digital skills are learned in formal courses and training or whether they are developed via informal social and public support and through self-study or practice.

The third section summarizes research into why people have different levels of digital skills. The causes are comparable with those we found in the stages of motivation or attitude and physical access. Are the same resources, positional and personal categories effective in the gaps in digital skills?

I will then explore the consequences of the differences of levels of digital skills. How do they affect the uses and outcomes of digital media? Will people with low levels of skill be excluded from society? Will a highly skilled information elite secure the best jobs and decide what happens in society?

The final section draws together the potential trends in the evolution of digital skills. Will ever more demanding and advanced skills be required in the future for employees, citizens and consumers, or will they be simplified because apparently accessible devices such as tablets are offered and because a growing number of applications work autonomously? Will the most recent skills be required for all people in the information and network society or for an information elite only?

Basic concepts

The core term

There are many terms that designate the individual ability to operate and use digital media. In the last twenty-five years those found most often are literacy, competence, capability, fluency, skill, and computer or web knowledge. The first term proposed in the 1980s and 1990s was computer literacy. Tobin (1983: 22) defined this simply as ‘the ability to utilize the capabilities of computers intelligently’. At the end of the 1990s Gilster (1997) extended this term to become digital literacy, which he defined as the usage and comprehension of information in the age of digital technologies – which means more than just computers.

Literacy is probably the most frequently used term, in combination with various adjectives: computer literacy, media literacy, digital literacy, information literacy and many others. The word ‘literacy’ has the connotations of reading or writing texts and cognitive processes such as understanding. However, researchers using this as the core term are also employing it for more comprehensive meanings (Bawden 2008). Media literacy, for example, is much broader than computer and digital literacy (Potter [1998] 2008; Hobbs 2011); it means being able to access, analyse, evaluate and create messages in a wide variety of media, including traditional media. It is often a normative concept too, because audiences are supposed to be critical in using media and their messages, and children in school have to be educated accordingly.

Competency is the most general term on the list. It often means having the capacity to evaluate knowledge appropriately and apply it pragmatically (Anttiroiko et al. 2001), notably in computer-mediated communication (Bubaš and Hutinski 2003; Spitzberg 2006) and in general Internet use (Carretero et al. 2017).

The most specific term is digital skills or e-skills, which focuses on (inter) action rather than on knowledge and its application. This interaction is with programs and web sources, as well as with other people (communication); it enables the transaction of goods and services and involves making decisions continually (van Dijk and van Deursen 2014: 140). Because the concepts of knowledge and literacy are so strongly associated with using more traditional media, I prefer to use the core term ‘digital skills’ in this book. However, in specifying these skills, I will show that particular knowledge and literacy are also necessary in order to attain specific goals in digital media use.

Literacy, competence or skill for which digital media?

In the previous chapter it was observed that there is an increasing diversity in types of digital media. To which of these do the concepts of digital literacies, competencies and skills apply? Working with advanced PCs, laptops, smartphones, feature phones, wearables, game consoles, Internet television and the Internet in general require different abilities. Some researchers refer to computer literacy, others to Internet skills. Most focus on one type of device and connection. In this chapter I propose a general framework of digital skills that applies to all digital media but concentrates on Internet skills, because it is the Internet that links and integrates all devices and connections.

The importance of technology change

Researchers into digital literacy, competence and skill are confronted with continual technological change. The evolution from PC to laptop to tablet, although retaining the same information and communication tasks, has demanded new skills of the user. The advent of the Internet of Things, marked by autonomous devices and systems, also requires fresh expertise: people have to evaluate and control these automatic decisions. Such examples demonstrate that digital literacy research has to react to a moving target of technological change.

General frameworks of digital literacy, competence and skill

In the last fifteen years multiple general frameworks, covering all digital literacies, competencies and skills, have been constructed and proposed to the scholarly and policy community (see summaries in van Deursen 2010; Litt 2013; and van Dijk and van Deursen 2014). It is very important to define any target group of people requiring these literacies or skills. In formal education they will be students, whose learning goals can be specified. In adult education, for instance, it might be the modules of a computer driving licence offered by training institutions in many countries. Training courses for employees can be designed for particular work tasks. For the general population, tuition in online digital skills is sometimes offered by local authorities and other organizations. Unfortunately, it is likely that businesses believe that their relatively simple and standard websites are easily managed by all consumers.

In this chapter I am concerned with basic digital media skills or competencies for the general public and, so, to establish a comprehensive framework aimed at everyone who wants to use a computer or phone with an Internet connection.

There are numerous proposals of such frameworks which cannot be discussed fully in this section. From 2001, Bawden formulated a number of very general ‘new literacies’, consisting of computer literacy, general information literacy, digital information literacy, network literacy and media literacy (Bawden and Robinson 2001; Bawden 2008). Warschauer (2003) offered five specific literacies: computer literacy (basic forms of computer and network operation), information literacy (the ability to manage vast amounts of information), multi-media literacy (the ability to understand and produce multi-media content) and computer-mediated literacy (managing applications such as e-mail, chatting and video-conferencing, and practising ‘netiquette’). Amichai-Hamburger et al. (2004) published the first experiments with assessments of five literacies: photo-visual (reading computer and Internet graphics), reproduction (to create new content from older material), information (evaluating information), branching (reading non-linear hyper-texts) and socio-emotional literacy (understanding the rules of Internet discourse), while Livingstone et al. (2005) offered a very broad list of literacy items for adults specified for every medium, both traditional and digital. Later, Livingstone and Helsper (2007, 2010) concentrated on Internet literacies and skills for children and teenagers.

A framework based on competencies was first proposed by Gilster (1997), who listed ten very general competencies, ranging from problem-solving and searching skills to critical judgement of contents found online and understanding network tools and hyper-text. Spitzberg (2006) itemized competencies of communication in e-mail and on the Internet. Finally, I come to The Digital Competence Framework for Citizens, by Carretero, Vuorikari and Punie (2017), published by the European Commission. The authors propose five general competence areas: information and data literacy, communication and cooperation, digital content creation, safety, and problem-solving.

The tradition of using skills as the core theme in research started with Hargittai (2002), who interviewed and assessed fifty-four randomly sampled Internet users in observational sessions and gave them tasks to find several types of information online. Bunz (2004) also asked for operational skills in using e-mail and websites to create a so-called computer–e-mail–web fluency scale. Van Dijk (2003, 2005) also proposed a framework to observe digital skills, which was elaborated and extended by van Deursen (2010) and fully described in the book Digital Skills: Unlocking the Information Society (van Dijk and van Deursen 2014). A summary is provided below.

Research strategies to investigate digital literacy, competence or skill

The basic concepts of digital literacy, competence and skill acquire different meanings through the ways in which they are observed, whether surveys, interviews, assessments or tests, and ethnography or field research.

The most frequent strategy is to conduct a survey with printed or online questionnaires or with interviews. Respondents are asked to report on their computer and Internet behaviour and rate their own performance in terms of literacy, competence and skills. Unfortunately, this strategy is poor in validity: most people overrate their performance, and males, especially young males, rate themselves higher than do females.

A relatively better type of survey is to ask proxy questions about the tasks, steps or procedures people have actually accomplished through using computers and the Internet. But the best strategy in validity and reliability is direct observation of performance. Hargittai (2002) Alkali and Amichai-Hamburger (2004) and van Deursen (2010) charged subjects in laboratory settings with tasks such as finding something on the Internet. The problems with this strategy are that it is very laborious and expensive and that only a small sample of subjects can be measured. So, in practice, researchers often turn to proxy questions in surveys.

The third strategy is ethnography or field observation. This means observing Internet users both online and offline and then interviewing them (Leander 2007). Tripp (2011) observed the Internet skills of Latino parents and children both at home and in the classroom, interviewed them, and analysed children’s homework for potential skills developed. This strategy offers a wide perspective of literacies or skills in the social context, but it involves only micro-settings and so presents no chance of generalization.

The specific framework of digital skills used in this book

In this section, my own general framework, developed in the last fifteen years with my colleague Alexander van Deursen, will be used for the following reasons to describe the most important specific digital skills (van Dijk 2005; van Deursen 2010; van Dijk and van Deursen 2014). First, all specific digital skills discussed in the remainder of the book can be directly related to this framework. Second, the framework is broad enough to cover most of the other literacies, competencies and skills previously mentioned. Third, it has been validated in several empirical laboratory assessments with representative groups of the Dutch population, in skill tests for employees, and in surveys with proxy questions for specific skills. Currently, it is being used in several international research projects, as it is part of the larger ‘from digital skills to tangible outcomes’ (DiSTO) approach (see www.lse.ac.uk/media-and-communications/research/research-projects/disto).

Before describing our framework, I have to explain that it follows a particular approach. The notion of digital skills is instrumental. While literacies focus on the perception, understanding and creation of contents and competencies on potential use and its results, skills concentrate on what users can actually do with and within digital media. They act and react with hardware, software and applications for a particular goal. The question is whether or not they are successful.

The framework has four other general characteristics (van Dijk and van Deursen 2014: 141):

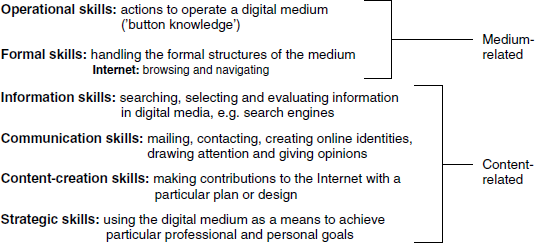

- A distinction is made between medium- and content-related skills.

- This distinction is sequential and conditional: without sufficient medium-related skills, content-related skills cannot be accomplished.

- The framework is empirical and not normative. For example, to assess information skills, only the accuracy and validity of information found in online sources and via search engines are evaluated.

- So far, the framework has been applied mainly to Internet skills, although it can easily be adapted to other (digital) media.

Special medium-related skills are involved in the use of digital media. For computers, the first requirement is operational skills. Users need to command keyboards and all kinds of peripherals, and they have to learn the interfaces of all programs and content, particularly operating systems and applications. Additionally, they need to understand the formal structures of the medium. Just like books, with their chapters, paragraphs, notes and indexes, computers and the Internet have specific structures. Computers have maps, files, menus and access codes and the Internet has websites, hyperlinks, fields for addresses and searches, and many other special entries. Browsing and navigating on the Internet is not as straightforward as people tend to believe. Obtaining the formal skills to find your way around the Internet requires exploration and practice.

In the 1990s these operational and formal skills were mainly understood as abilities of a technical kind, command of which was believed to solve the skill problem. In the first decade of the twenty-first century, information literacy, competence or skill was added to the mix. Information skill – the ability to search, select and evaluate information online – is the first and most important of these and involves, for instance, a systematic and accurate use of search engines. The evaluation of information is a critical accomplishment. An example is tackling disinformation or ‘fake news’. An empirical approach towards evaluating information might detect only specific statements as being evidently ‘fake’; a normative approach encounters problems in evaluating many more statements because almost every news item is biased to a certain extent.

Communication skills involve the effective use of e-mail and other message applications and the ability to contact people online successfully, to construct an attractive profile online, and exchange information or give opinions. Such skills are becoming more and more important in the network society.

The third type of content-related skill is content-creating skill. Most people contributing to the web are amateur writers, moviemakers and musicians, not professionals, and the quality of what they produce is highly diverse. A minimum of writing and creation skills is required to be effective and attractive in a web environment.

The last type of digital skill, and the one most difficult to achieve, is the strategic skill of using the Internet as a means to reach a particular professional and personal goal. Strategic skills require the mastering of all the other skills. None of the four content-related skills can be deployed without sufficient operational and formal skills, and strategic skills cannot be achieved without information, communication and content-related skills. Additional strategic operations are needed to work with privacy settings and security aids on the Internet.

I will give two examples of professional and personal goals. Writing a letter or application for a job requires first the information skill to find that suitable post among the many thousand online. Communication skill is needed to write an e-mail introducing a convincing application letter, and content-creating skill is necessary to write the letter and to generate an effective job profile. Second1ly, looking for a partner though online dating needs information skill to select the preferred candidate from a huge pool of contenders, content-creating skill to represent an attractive profile, and communication skill to write an effective introduction or invitation in order to realize the strategic skill of addressing the best match available.

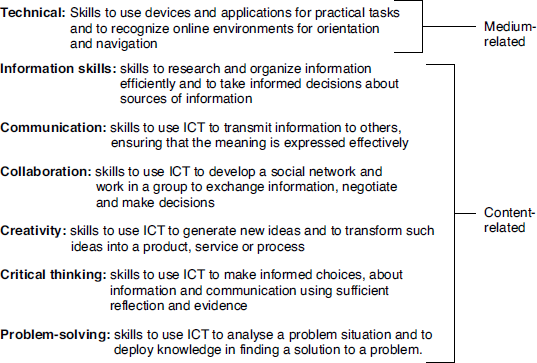

Figure 5.1. A general framework of six medium- and content-related digital skills

These six conditional and sequential skills are summarized in figure 5.1. Medium-related skills are needed to realize content-related skills. In a wealthy country such as the Netherlands, with 98 per cent Internet access, the majority of the population has sufficient medium-related skills, but most strategic skills are mastered by only about 20 per cent of the population (van Deursen 2010, van Deursen and van Dijk 2015a). The six digital skills of the framework are specified for the Internet by van Dijk and van Deursen (2014: 42).

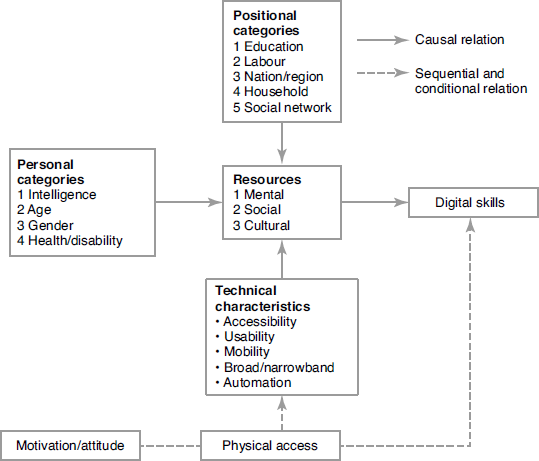

Causes of divides in digital skills

Divides in digital skills can be explained by people’s resources and positional or personal categories. Digital skills primarily require cognitive characteristics such as intelligence, knowledge and technical ability, though motivation also remains important.

Resources supporting digital skills

Evidently, if people do not have sufficient material and temporal resources, they will not develop digital skills. However, we will see that, while considerable Internet experience is likely to support medium-related skills, there is no guarantee that it will help develop content-related skills (van Deursen and van Dijk 2011).

Mental, social and cultural resources, then, are more important for explaining differences in people’s digital skills. Mental resources – technical proficiency or know-how, knowledge of technological and societal affairs, and analytic capabilities – are the most significant. Søby (2003), Mossberger et al. (2003) and Carvin (2000) found that technical proficiency or competence – an accumulated knowledge of hardware, software, applications and connections – is a basic component of digital literacy. It is well known that people turn to tech-savvies to help them with technical problems.

Most people do not develop digital skills on their own, and their social context is very relevant when they meet problems and require assistance. However, not everyone benefits from the social resources of colleagues, family members and friends with better skills or is able to consult a help desk or find a computer course.

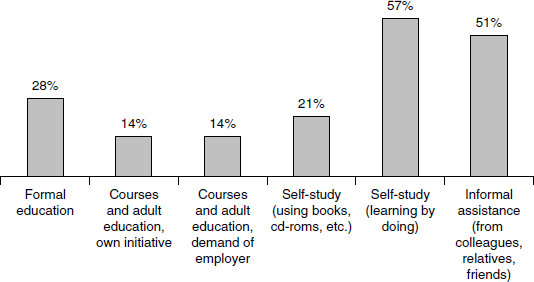

figure 5.2 shows the various ways of acquiring computer and Internet skills in the European Union. Unfortunately, the statistics date from 2011, but in my estimation they are an indication of a distribution that still holds, and not only in the EU but also elsewhere. The figure shows that informal ways of acquiring digital skills are much more important than formal ways. Seeking social support from others is the second most common course of action.

Figure 5.2. Ways of acquiring computer and Internet skills in the European Union

Source: Eurostat, Internet Use in Households and by Individuals in 2011.

Van Deursen et al. (2014) created a typology of users acquiring digital skills and, in a representative survey of the Dutch population, found that their characteristics confirmed the distribution shown in figure 5.2. The first group, the independents, learn skills by doing or through trial and error, though they might also make use of manuals, DVDs or websites. This type significantly consists largely of young, male and highly educated people. The second group, the socially supported, ask colleagues, relatives and friends for assistance when they find a problem. This type is made up mainly of seniors, females and people with low education. The third group are the formal help seekers, who follow classes of formal adult education or special computer classes and courses, either on their own initiative or via their employer. They also consult computer experts and help desks. Formal help seekers are mainly employed, relatively old, and have followed low- or medium-level education.

According to surveys, the independents have the highest levels of all kinds of skills. The socially supported learn some operational and formal skills but no information or strategic skills. This mode of learning is unreliable because relatives or friends often provide partial or wrong solutions and answers. Thus, the socially supported are the worst performers, even in operational and formal skills. Unfortunately, people with the lowest digital skills obtain the worst social support (Helsper and van Deursen 2017; van Deursen et al. 2014). Formal help seekers obtain information and strategic skills in their courses and classes.

As far as cultural resources are concerned, a lifestyle that involves using digital media throughout the day, and for every imaginable purpose, makes it easier for such ‘digirati’ to develop their skills (Ragnedda 2017), especially operational and formal skills. The status earned by an expert in the operation of ICT stimulates their motivation to maintain their reputation by acquiring even more skills. Advising people also helps such experts to have a better understanding of problems. Finally, status markers motivate owners who have purchased a number of flashy new devices and apps to master them thoroughly in order to demonstrate them to others.

Positional categories determining resources and digital skills

The first series of background factors determining all these resources are positional categories. In all observations of digital skills, literacies or competencies, by both assessments and proxy survey questions, the attainment of education, whether in school or via adult education, is the most important factor (Bonfadelli 2002; Gui and Argentin 2011; Hargittai 2010; van Deursen 2010; van Deursen and van Dijk 2009, 2011, 2015b). Van Deursen (2010) and van Deursen and van Dijk (2009, 2011) have found in both laboratory assessments and surveys that people with higher education perform better, particularly in content-related skills and strategic decision-making.

An individual’s labour position is the second important category explaining differences in digital skills. Clearly, people with a job that requires the use of computers have more opportunities to improve their skills (van Deursen and van Dijk 2012).

On average people in a developing country have fewer opportunities to learn digital skills, even when they are part of the elite, than people in a developed country. The availability and quality of a nation or region’s information and communication infrastructure, together with its educational institutions, dictate the opportunities available to the population. Unfortunately, there is no international comparative research concerning the level of digital skills attained by different countries. Institutions such as the World Bank (2016), the Economist Intelligence Unit (2019) and Unesco (Broadband Commission et al. 2017) have tried to estimate the national level of digital skills mainly through educational performance.

People living in multi-person households clearly have more opportunities to improve their skills. In particular, parents can help their children with content-related skills, though many children have better medium-related skills than their parents.

The final category is a position in a social network. People with large social networks are the first to receive strategic information from others in their circle (Kadushin 2012), a position that allows them to ‘hoard’ all kinds of opportunities (Tilly 1998). In every society there is a big overlap between the information elite and the social, economic, political and cultural elite.

Personal categories determining resources and digital skills

The most important personal category determining technical proficiency, knowledge and analytic capabilities is intelligence and the technical ability to understand and operate digital technology. Unfortunately, these have not been directly measured in digital divide research, where IQ tests are rarely conducted. Intelligence and technical ability are sometimes tested in research in computer classes and the like in schools. However, the results are valid only for the particular course and not for the levels of intelligence and digital skills in the general population.

In my view, digital divide research has turned a blind eye to the importance of intelligence. In most research, education has been found to be the most significant background factor in the digital divide and so is the most important key to solving this problem. However, what actually explains the role of education in differences in skill?

Whether we like it or not, natural science has shown that intelligence is partly hereditary (Lee et al. 2018). Intelligence is related to the ability to process information. According to Guilford (1967), this requires five mental operations: 1) to recognize information quickly and to give it meaning, 2) to recall information immediately, 3) to find many solutions to problems, 4) to bring different things in a common denominator and 5) to evaluate information to make a judgement. Clearly, these mental operations are needed for content-related digital skills, especially information and strategic skills.

Technical ability is a kind of practical intelligence related more to medium-related than to content-related skills. At all levels of education some people are more tech-savvy – ‘being good at computers’ and the like – than others.

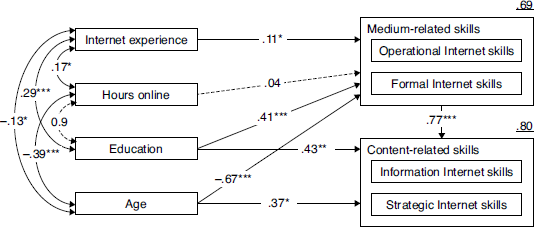

In contrast to the other personal categories, age is frequently investigated in digital skills research. The general conclusion is that young people are better than older people in medium-related digital skills, but the results are mixed as far as content-related skills are concerned (Litt 2013). A popular notion is that young people are better at using digital media and the Internet, and new terms have been created to describe them, such as ‘digital natives’ and ‘net generation’ (Tapscott 1998; Prensky 2001). However, this notion largely is a myth: in fact, the level of digital skills among the young generation is very wide-ranging (Hargittai and Hinnant 2008; Hargittai 2010; Helsper and Eynon 2010; Calvani et al. 2012). What is more surprising is that research has shown that older generations might be better at using the Internet than the young! This is explained by the fact that young people have better medium-related skills such as ‘button knowledge’ and fast navigation, while seniors have superior content-related skills (provided that they have sufficient medium-related skills to start with). Figure 5.3 is a causal model of the results of a representative Dutch survey that supports these statements (though note that communication and content-creating skills were not measured in this survey). The figure shows that increasing age has a negative impact on medium-related skills and a positive effect on content-related skills. While older people have less Internet experience and spend fewer hours online than young people, experience is barely significant and the number of hours spent online is not meaningful. Adequate medium-related skills are needed for content-related digital skills to be developed. Finally, the figure shows that age and education are very important personal categories affecting the level of digital skills. These results have been confirmed in other countries by Alkali and Amichchai-Hamburger (2004), Helsper and Eynon (2010) and Gui and Argentin (2011).

Figure 5.3. Causal path model of four independent factors explaining digital skills

Source: van Deursen et al. (2011).

Gender is the third personal category often investigated in digital skills research, though most does not find significant differences between the skills of males and females (Litt 2013) – at least, not in advanced high-tech countries. The situation might well be different in developing nations and in countries where there is a lack of female emancipation. I have already stated in this book that people, especially (young) males, overrate the level of their skills as compared to the objective results of tests. Just before conducting his laboratory assessments, van Deursen (2010) gave a questionnaire to all participants and asked them to rate their own level of skill. While males rated their expertise at a much higher level than did females, the actual performance of both in the assessment was shown to be equal. The same observation was also made by Hargittai and Shafer (2006) and Hargittai and Hinnant (2008).

The last personal categories to be discussed are health or disability and illiteracy. Disabled people are less likely to go online than the able-bodied (Dobransky and Hargittai 2016), and the disabled on average show lower levels of skill (van der Geest et al. 2014; van Dijk and Van Deursen 2014: 129–31). Complete and functional illiterates will have no content-related and very few medium-related digital skills since they cannot handle words, documents or the names of menus or links. The Human Development Report 2009 (UNDP 2009) estimated the proportion of functional illiterates to be 20 per cent in the US, 22 per cent in the UK and 7.5 per cent in Sweden (the lowest figure). The number of illiterate people in modern society, let alone in the information and network society, is a persisting problem that is very difficult to solve.

Figure 5.4. Causal and sequential model of divides in digital skills

The various causes of inequality in digital skills are shown in figure 5.4. The order of factors in the boxes is estimated.

Technical characteristics

Finally, there are a number of technical characteristics of contemporary digital media that affect the possibility of developing digital skills. The first of these is accessibility. Being able to access the same kind of hardware, software and applications – for instance at work, in school, at home, while commuting or at public access points – is particularly helpful when one is learning digital skills. Taking advantage of mobile access at all times is an option. However, many applications can better be performed on PCs or laptops, with their bigger screens, keyboards and often faster connections (see the characteristic of mobility below).

The second characteristic is usability – the ease of use and learnability of the hardware, software and applications. Shneiderman (1980) and Nielsen (1994) have created a framework for usability with the following attributes: learnability (the ease of accomplishing a basic task), efficiency (how quickly this task may be performed), memorability (remembering how to carry out a certain task), correction of errors (how many errors are made and how they can be recovered) and satisfaction (the pleasure of using the tool). All of these affect the learning of digital skills.

Another characteristic of usability is the intuitiveness of a device or application. Tablets and smartphones are relatively easy to use instinctively by, for example, dragging horizontally or vertically across the screen with your finger. Intuitive use can help with the development of medium-related skills. However, ease of use also is deceptive: it both seduces us to avoid learning more difficult content-related skills (van Dijk and van Deursen 2014: 99–101; van Deursen et al. 2016), and it stimulates constant following, swiping and tapping on links, words or pictures presented on the screen rather than encouraging input of content by users themselves.

The third technical characteristic is mobility. This offers the same tradeoffs as usability. People who are able use the same digital media at all times and in all places have more chances of learning the required medium-related skills. However, users tend to avoid the more advanced applications offered on PCs and laptops (Bao et al. 2011; Napoli and Obar 2014), meaning that they also learn fewer content-related skills (van Deursen and van Dijk 2019). (See more about this in chapter 6.) Broadband as compared to narrowband connections do not show the same trade-off. Broadband is always better for both medium- and content-related skills, as many more visual cues of understanding are presented and many more and diverse advanced applications are offered (Mossberger et al. 2012). Pictures and videos can be downloaded and uploaded quickly and response times in all interfaces are much shorter.

The final important technical characteristic is automation. More and more applications are now offered that work on the basis of artificial intelligence. In the context of the Internet of Things, augmented reality and personal assistants (provided in search engines or with smart home devices), more and more decisions are made via algorithms. Users need to learn only a few additional operational skills to utilize their health and sport wearables, smart watches and glasses, self-driving cars, energy meters at home, online heating and kitchen remote controls, search engines for assistance, and many others. The devices and their intelligent software do all the work.

This means that information, communication and content-creation skills would seem to be less important. Even strategic skills may no longer be needed when smart applications take the decisions. However, in truth they are needed more (van Deursen and Mossberger 2018). Users need to know first whether it is actually smart to purchase these applications and whether the decisions made would be their own preferred decisions. Using these technologies people are additionally confronted with systems – transport systems, energy provision, health care and assurance systems, and provider systems of platforms such as Google. Understanding these systems requires more knowledge than most people actually possess. In fact, advanced strategic skills are needed, a type of content-related skill least performed by the average user (see above). Again, this technical characteristic is a trade-off of a technology that makes it both easier and more difficult for users to learn the required digital skills.

The consequences of divides in digital skills

Having sufficient digital skills is a turning point in the whole process of adopting technology. It is most likely that people with a high level of digital skills will be the most frequent users of all types of media, while those with a low level of skills will use them only for relatively simple or attractive tasks such as personal communication, e-shopping and entertainment. The final result is that such people will gain fewer benefits and those with a high level of digital skills will benefit more and suffer less harm from its negative aspects (security and privacy problems, cybercrime, cyberbullying and other abuse; see chapter 7).

The causal links between digital skills, frequency and diversity of use, and positive or negative outcomes are demonstrated in nationwide survey results from several countries (Helsper 2012; Pearce and Rice 2013; van Deursen and van Dijk 2015b; van Deursen and Helsper 2015; van Deursen et al. 2017).

Another consequence of the differences in mastering digital skills is that the already strong position of the information elite in society, the professional-managerial class, academics, government officials and businessmen, will become reinforced (Michaels et al. 2014). Conversely, the already feeble position of people with low education in manual or unskilled jobs will become even weaker in an information society. Such workers are at permanent risk of their jobs being eliminated by automation and robotization; their wages tend to stagnate or be cut. In the meantime, people with higher education and average or advanced ICT skills earn a ‘skills premium’ (Nahuis and de Groot 2003); these skills are substantially rewarded in the labour market (Falck et al. 2016; O’Mahoney et al. 2008). The use of ICT has polarized skills demand in the last twenty-five years: instead of requiring staff with medium-level education, industries now call for people with higher education and high digital skills (Michaels et al. 2014).

A similar polarization occurs among those enrolling in educational institutions. The higher the level of courses, the greater are the digital skills needed to follow the programme of study and to succeed in exams. Today, it is impossible to pursue higher education without sufficient digital skills.

The evolution in the level and nature of digital skills

In the last ten years the absolute levels of digital skills attained by the general public have increased, as have the relative differences in skills attained by particular groups (van Deursen and van Dijk 2015a). This means that people of every social class, age and gender, and with all levels of education, have developed higher skills, especially medium-related skills. However, relative gaps in mastering digital skills between those at the higher and lower ends of educational attainment and labour position have also grown, though they do not seem to occur as far as gender and age are concerned: females and seniors are now catching up with males and the young, at least in the developing counties.

Two opposing trends will decide the future of digital skills. The first consists of the growing requirements that our societies and advanced technologies impose on the use of ICT: the complexity of both is increasing. More and more difficult tasks are set for and performed by digital media in all ways of life. These tasks require much information processing, abstract thinking and strategic decision-making, meaning that the necessity for content-related skills will increase.

The other trend is composed of the affordances of new technology: new methods of carrying out existing tasks will tend to require simpler skills. Speech and face recognition, replacing the need to use keyboards, and images and speaking inputs and outputs replacing texts will reduce the demands on medium-related skills. For example, instead of using a textual search engine, individuals can speak to a ‘personal assistant’. New artificial intelligence software will help users to make decisions, thus reducing the requirements of content-related skills. However, the operations and communications performed by digital technology will not be reduced: people, organizations and societies want more and more complex tasks to be carried out in this manner. For example, the advent of the Internet of Things might lead to fewer demands on medium-related skills but more demands on making decisions about the acceptance of the advice given and the service of the systems offering such applications (van Deursen and Mossberger 2018). Will I accept the advice of my wearable smart watch to take more steps a day? Is it wise to transmit the data provided by this device concerning my performance to my doctor and health insurer? More strategic digital skills are needed for this purpose than before.

The demands on content-related digital skills are also increasing on account of the requirements of so-called twenty-first-century skills. These substantial cognitive and behavioural skills are very similar to content-related digital skills. The most popular frameworks have been made by the Partnership for 21st Century Skills (2008) and Binkley et al. (2012). Following a systematic literature review, van Laar et al. (2017) created a list of core twenty-first-century digital skills (see figure 5.5). These authors also found some additional skills in the literature – self-direction, ethical and cultural awareness, lifelong learning skills and flexibility skills – though these will not be discussed here.

Figure 5.5. Framework of core twenty-first-century skills

Source: Adapted from van Laar et al. (2017: 583).

These seven core skills are content-related, and digital media or ICTs are among the most important tools to realize these skills. Today there are effective, reliable and valid search engines, online personal assistants and other applications to find, process and evaluate online information. Communication these days requires an appropriate and effective use of e-mail, social-networking sites and messaging services. Collaboration often involves content management systems, wikis, document cooperation among groups, and chat platforms. Creativity can be enhanced by an appropriate use of tools to devise online content. Critical thinking, defined as observable informed choices, is required in using search tools and evaluating any information or disinformation on the web. Problem-solving skills can be improved by an effective use of various online tools, from search consoles (advanced search engines) to development apps.

It is to be expected that professional workers, e-participating citizens and experienced e-commerce consumers with a high level of educational attainment will be the first to develop these twenty-first-century skills, but this is not yet supported by empirical research. Meanwhile the need for medium-related skills at a basic level will continue or even be reduced. We should bear in mind, however, that the number of digital devices and programs is multiplying with the rise of the Internet of Things and virtual or augmented reality, all of which require a number of additional operational skills.