7

Outcomes

Introduction: who benefits and is harmed by digital media use?

After having described the causes and consequences of the phases of appropriation of digital media, we have now arrived at the result of this process. What are the hazards of (not) using digital media? Does it matter if one has no access to the Internet, has insufficient digital skills and is an infrequent user, for example? It might be that traditional media remain adequate for many aspects of daily life, including work and education. We cannot rule out the fact that particular offline activities may be just as good as, or even better than, comparable online activities.

How can we understand these questions? Are they problems as far as economic growth, employment and innovation are concerned? Is there a problem of people being excluded from society and participation in all kinds of domains? Or is there a security problem because people cannot be easily registered and controlled by governments and businesses? These three perspectives were the main approaches of the digital divide as discussed in chapter 1. In this chapter I am choosing the second perspective: inclusion in or exclusion from society. In my former book about the digital divide (van Dijk 2005) I took the normative perspective of participation in the labour market, the community, politics, citizenship, culture, etc. Here I am taking a more neutral and empirical approach: which positive and negative outcomes of digital media use have been observed? Up until now, digital divide research has been concerned with positive outcomes, outcomes achieved by people with digital access, skills and use. In this chapter, negative outcomes – excessive use, cybercrime or abuse, and loss of security or privacy – will be discussed. The question is what outcomes are achieved by people with an adequate level of access to digital media, together with the skills for their use.

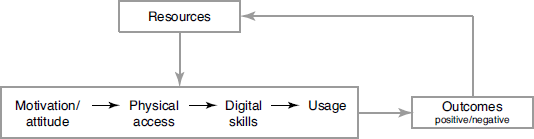

The causal process behind the argument in this chapter is that following the four phases of technology appropriation will lead to positive or negative outcomes. These outcomes then lead to the same resources causing the four phases of appropriation. This is a feedback loop of reinforcement, a core statement of resources and appropriation theory as discussed in chapter 2. This particular statement is a case of structuration theory (Giddens 1984). In structuration theory, social structures influence actions, and actions affect these structures, a duality of reinforcement. In resources of appropriation theory, resources influence the process of appropriation, and the outcomes of this process reinforce the resources in a feedback loop. The argument is portrayed in figure 7.1. Supporting the resources are lists of both positional and personal categories as used previously. Via motivation/attitude, physical access, digital skills and usage, these categories will be related in this chapter to positive and negative outcomes.

Figure 7.1. Causes and consequences of digital media appropriation for outcomes and the reinforcement of resources

The second section will frame the term ‘outcomes’. These may be positive or negative, absolute or relative, concomitant or separate, online or offline, and traditional or digital media outcomes.

The third section is about the positive outcomes of digital media use. They are listed according to familiar domains of social and daily life: economic, social, cultural, political and personal. The most important potential outcomes for society and individuals will be discussed, related to positional and personal categories and added to a final score.

This is followed by the negative outcomes, which are clustered in three parts: excessive use, cybercrime or abuse, and loss of security or privacy. After this we will be able to see whether people who enjoy positive outcomes are also able to prevent negative outcomes.

The final section of this chapter draws up a balance sheet. What is the final situation with the digital divide? Considering all these positive and negative outcomes, are we able to conclude that the effects of digital inequality are increasing or decreasing? Which categories of society benefit more and are harmed less by the use of digital media? The answers are given in the following chapter, where digital inequality will be related to existing social inequality.

Framing the outcomes

The ‘third level’ of digital divide research (see chapter 1), which is a fairly recent focus, is to do with observing the outcomes. While the term was first used in 2010, empirical research of outcomes in terms of benefits started a few years later. Helsper and van Deursen (2015, 2017) undertook the most extensive surveys, in the UK and the Netherlands, showing the lack of equality in achieving benefits. Unfortunately, by that time the focus of most research was on positive outcomes. This is not surprising given that, from the start, all digital divide perspectives had focused on loss of economic growth, employment or innovation, the lack of participation or inclusion, and the failure to register or control citizens. After 2015 the general public became more aware of the negative consequences of the Internet, particularly in relation to social media, the rise of cybercrime and all kinds of abuse, problems of disinformation, hacking, and excessive use.

Blank and Lutz (2018) were the first to investigate these negative outcomes. In their survey in the UK they asked participants whether they had experienced six specific harms: ‘In the past year have you ever … received a virus onto your computer? … bought something which was misrepresented on a website? … been contacted by someone online asking you to provide bank details? … accidentally arrived at a pornographic website when looking for something else? … received obscene or abusive e-mails? … had your credit card details stolen?’ While people on the right side of the digital divide clearly amassed the benefits of Internet use, the results concerning harms from using digital media were mixed for people on both sides of the divide. A similar conclusion will be drawn below after discussing a much longer list of negative outcomes.

A second type of framing is the estimation of outcomes. Are they absolute or relative? We will see that they are relative. Everybody who uses digital media experiences both positive and negative outcomes, some more than others.

Thirdly, outcomes may be observed separately and in combination. In this chapter we cluster them in linked domains of society For example, people gaining benefits from using social-networking sites might also discover more opportunities to find a job or a particular product in the economic domain. We will show that the economic and social domains and the cultural and personal domains are most closely related.

Finally, wherever possible, outcomes online have to be compared with similar offline outcomes. The same goes for digital and traditional media use. What is the difference between finding a job online and doing so through using traditional media? An example of a question that might be asked here is: ‘Without using the Internet, I would not have found a job. Yes/No’. In other words, a traditional job search would not have led to this positive outcome.

Positive outcomes of digital media use

Positive outcomes of digital media use are benefits generally endorsed by most contemporary societies. In the economic domain they are, for example, finding a job or lower prices for products or services. In the social domain they might be more and better contacts or relationships and contributions to the community. In the political and civic domain they might be voting in elections or receiving public and social benefits. In the cultural domain examples are attending, sharing or contributing to cultural events. In the personal domain they might be finding an educational course or benefiting from health information.

Table 7.1 lists the most important positive outcomes in all these domains that were part of nationwide Dutch and British surveys conducted by van Deursen and van Dijk (2012), Helsper et al. (2015), van Deursen and Helsper (2018) and Van Deursen (2018). Van Deursen and van Dijk (2012) and van Deursen (2018) posed questions such as ‘By using the internet I obtained X: Yes/No’. Helsper et al. (2015) and van Deursen and Helsper (2018) asked not only for objective achievement but also for subjective satisfaction – for example, whether finding a romantic date online was satisfying. However, future survey questions need to become more valid and reliable, because answers may be biased and lack sufficient detail. So, one needs to be circumspect in accepting the data presented.

Economic domain

Positive outcomes in the economic domain for individuals are threefold and concern work and schooling, e-commerce (buying and selling online) and income or property. Digital media have become a necessity in most parts of the world as far as work and education are concerned. Both searching and applying for a job are now done mostly online, and those who lack the access or skills to do this are increasingly excluded from the labour market. Approximately three-quarters of Internet users who have found employment, at least in the UK and the Netherlands, claim that they have found a job online they would not have found otherwise (van Deursen and van Dijk 2012; Helsper et al. 2015).

Table 7.1. The most important positive outcomes of Internet use as achievements

Source: Information from van Deursen and van Dijk (2012); Helsper et al. (2015); van Deursen and Helsper (2018).

| Domain | By using the Internet I … |

| Economic | –found a job opportunity – found a job – improved my work (tasks) – earned a higher wage – saved money buying a product or service online – saved money selling/sharing a product or service online – saved money investing in stocks or shares online |

| Social | –found friends I subsequently met offline –found a romantic date I subsequently met offline –have more contact with family, friends or acquaintances –have better contact with family, friends or acquaintances –found people sharing my interests –discovered an opinion online or added a new one –became a member of an association or community |

| Political/civic | –signed a petition online –contacted a representative, party or government department –became a donor of a political or civic organization |

| Political/civic | –became a member of a political or civic organization –voted after finding political information or using a voting aid –received better government information online –received a public or government service online –found a benefit, subsidy or tax advantage online |

| Cultural | –found a ticket online for an event or concert –found entertainment (games, music, video) not available offline –became a member of a hobby, sports or cultural club –changed lifestyle choices after receiving information online –created cultural content not available offline |

| Personal | –recognized my identity finding people with the same interests –found a course or study that fits me –completed a course or study outline –improved my health after finding health information online –found (more) about my disease – found a hospital or clinic to help me more quickly or to a greater degree |

A majority affirm that they have found improvements in their job in terms of speed or productivity, through increasing flexibility and variety, and by receiving a greater number of courses (for using ICT) and more contacts with colleagues (van Deursen and van Dijk 2012). Finally, it has been confirmed from several sources that being able to use ICTs leads to a premium in wages (see chapter 5). All these positive employment outcomes have benefited the young (those aged sixteen to thirty-five) and people in the higher professions more than older (aged fifty-five plus) and nonprofessional workers (van Deursen and van Dijk 2012; van Deursen 2018).

Also in the economic domain is the market of products and services. For consumers – which means everybody – the advantages of e-commerce (buying and selling products and services) are among the most attractive benefits of Internet use. Large majorities assert that they have saved money buying a product online rather than in a shop and close to a majority that they have sold goods online that they wouldn’t otherwise have sold. Again, young people and the higher educated benefit more (van Deursen and van Dijk 2012; Helsper et al. 2015; van Deursen 2018).

The third economic subdomain is property and income. A majority of people in the developed countries are now using Internet banking. The wealthy also are investing in stocks and shares. However, this minority need to have sufficient financial knowledge and a high level of information and strategic digital skills.

The conclusion here is that young people, particularly males, those with higher education or income, and the employed have statistically significant advantages of Internet use in this domain (van Deursen and Helsper 2018; van Deursen 2018).

Social domain

The use of digital media and especially the Internet offers many opportunities for social contact, civic engagement and sense of community; this was realised early on (e.g. Katz and Rice 2002; Quan-Haase et al. 2002), though some scholars doubted it (e.g. Nie and Erbring 2002; Putnam 2000). Twenty years on, the average American claims that helping people connect is the second best thing about the Internet after easier access to information (Pew Research Center 2018). Research involving nationwide surveys shows that a majority confirm they have found new friends online (and have subsequently met them in person) and that they also received more contacts (van Deursen and van Dijk 2012; Helsper et al. 2015). At least one-third of the Dutch population say that they have formed a better relationship with friends and family (van Deursen 2018).

Online dating is popular today and is becoming a real alternative to dating in traditional ways. More than 10 per cent of couples met online in the Western world (van Deursen and van Dijk 2012; Smith and Page 2016). The Internet is also helpful in finding people with the same interests or opinions, an activity performed by a majority of Internet users (see Helsper et al. 2015 for the UK). Finally, individuals can become members of associations or communities online, though this is realized by a relatively small minority of Internet users today (van Deursen and van Dijk 2012; Helsper et al. 2015; van Deursen 2018).

It would appear that these outcomes are achieved much more by young people than by older generations, although there is no significant difference in terms of level of education and income (van Deursen and Helsper 2018). This is because the use of social media is widespread and very popular.

Political and civic domain

Generally, there is more civic participation (using government services and engaging with local communities online) than political participation. Though in most countries a majority of people continue to go to the polls at election time, online political participation is a minority affair (Boulianne 2009; Anduiza et al. 2012; van Dijk and Hacker 2018). The most frequent activities are retrieving political and election information, discussing political affairs, mailing or messaging a political representative, and signing online petitions (Smith 2013). Nevertheless, a substantial minority in the UK secured a better contact with an MP, local councillor or political party (Helsper et al. 2015), while those in the Netherlands decided which party to vote for by using a voting aid (van Deursen and van Dijk 2012).

It would seem that people who are specifically interested in politics are benefiting most in this domain. Generally, such people are highly educated and have good incomes (Jorba and Bimber 2012; Smith 2013; van Dijk and Hacker 2018). The surprising finding is that it is older generations more than the young who are benefiting from online political applications (Smith 2013; Mounk 2018; van Dijk and Hacker 2018), probably on account of different motivations.

In developed countries, where people are increasingly forced to use online government services, there is a more widespread use of civic applications. However, we found the same inequality of access, skills and use as in most other domains: people with higher education or income and the young are benefiting most from more and better government information and services (van Dijk et al. 2008; United Nations 2014). Most telling is that a quarter to half of Dutch and British citizens claimed the discovery online that they were entitled to receive a particular benefit, subsidy or tax advantage that they would not otherwise have found (van Deursen and van Dijk 2012; Helsper et al. 2015; van Deursen 2018).

Cultural outcomes

Cultural use of the Internet is also very popular. Even novice users find music, video and games online that are not easily available elsewhere. Almost everyone has on occasion made an online reservation for an event. A much smaller majority of the Dutch and British population confirms that they have become a member of a hobby, sports or any other cultural club or that they changed their lifestyle after finding cultural information online (van Deursen and van Dijk 2012; Helsper et al. 2015; van Deursen 2018).

The number of people creating content online depends on the nature of that content: for example, 75 per cent of the British population have posted photos and shared them on social-networking sites, uploaded music and video, written a blog or set up a personal website. Creating skilled, professional-looking content was achieved by 34 per cent but political content only by 14 per cent (Blank 2013).

By far the most personal characteristic showing statistically significant differences in cultural outcomes is age, not level of education or gender (van Deursen and Helsper 2018), and young people manifest the greatest benefits in online cultural outcomes, even where skilled content creation is concerned. Social and entertainment content, however, is produced more by people of lower education (Blank 2013).

Personal outcomes

There are all kinds of personal benefits to be gained from using digital media or the Internet: two very important, even vital, benefits are personal development (identity and education) and health. A majority of Internet users manage to find people with the same interests, while a minority of British and Dutch users have found or completed a course of study online (Helsper et al. 2015). On the other hand, a majority of these users affirmed in 2012–15 that they had found details about their disease, improved their health after retrieving information, and secured better or faster health care after receiving advice online (Helsper et al. 2015).

Van Deursen and Helsper (2018) observed that people with a higher level of education achieve such personal outcomes more than do people with lower education. Remarkably, older generations are also benefiting more (especially where health and adult education are concerned) than the youngest generation.

Relations of domains and their outcomes

Helsper (2012) claims that economic, social (including the political and civic domain), cultural and personal domains are interrelated. For example, someone who finds information concerning a job opportunity via a social-networking site may be able to secure the job in the economic domain. While the economic domain was generally found to be relatively separate, a strong link was found between social and cultural domain achievements in Dutch and British surveys (Helsper et al. 2015). However, the most frequent interrelation found is between the personal and social and cultural domains (van Deursen and Helsper 2018). The achievement of positive outcomes is found to be higher for economic and personal than for social and cultural outcomes (Helsper et al. 2015). The online benefits in the economic and personal fields are higher than in the social and cultural field, where traditional media offer face-to-face alternatives.

Negative outcomes of digital media use

As previously mentioned, the negative outcomes of digital media use have become widely discussed in society only recently. They are the last focus in digital divide research (Blank and Lutz 2018). There are so many potential negative outcomes that it is difficult to classify and analyse them. Both a selection of experts and a representative sample of the American population found that the benefits of digital media for society and daily life were overwhelmingly positive (Pew Research Center 2018; Smith and Olmstead 2018). However, a small, albeit growing, number of experts and the general public were concerned about the negative outcomes. The experts mentioned mainly psychological characteristics: information and communication overload, problems of trust regarding security and privacy, especially in relation to the big Internet platforms, personal identity problems such as a loss of self-confidence or self-esteem, a negative world-view after using the Internet, and failures of concentration. The survey of ordinary Americans, also published by the Pew Research Center (Smith and Olmstead 2018), revealed the answers that the Internet ‘isolates people’ (25 per cent), produces ‘fake news or misinformation’ (16 per cent), is ‘bad for children’ (14 per cent), ‘contains criminal activities’ (13 per cent) and damages ‘personal information or privacy’ (5 per cent).

Table 7.2. The most important negative outcomes of Internet use as liabilities

| Domain | Problems |

| Excessive use | –Addiction to the Internet and other digital media –Extreme stress in using the Internet and other digital media –Information overload –Loss of concentration –Lack of sleep –Lack of exercise –Lack of face-to-face communication |

| Cybercrime and abuse | –Financial fraud or theft –Extortion or blackmail (ransomware) –Identity theft –Criminal hacking of another’s computer or connection –Bullying –Harassment –Provocation in Internet discussions (e.g. ‘trolling’) –Spam –Creation of disinformation |

| Loss of security and privacy | – All intrusion in a computer or smartphone – Data theft –Receipt of a computer virus or spyware/malware –No (attention to) privacy settings and agreements –Concerns about and inadequate use of passwords –No or inadequate computer protection: anti-virus programs, firewalls, automatic updates, spam-filters, pop-up blockers, anti-spyware |

In this section I will deal with potential negative outcomes in three sections: excessive use, cybercrime or abuse, and loss of security or privacy (see table 7.2). These are individual negative outcomes rather than societal outcomes (for the latter, see, among others, van Dijk [1999] 2012). The discussion will relate these negative outcomes to the digital divide problem, looking at distinctions of age, gender, and social class and status (income, income and lifestyle).

To discuss these negative outcomes in a digital divide perspective we will look at the risks encountered by particular users and at the way they cope with these risks. People on the right side of the digital divide who are frequent users are more likely to encounter these risks; however, with their experience and skills they may also be better at coping with such risks.

Excessive use

Excessive use of digital media ranges from using a computer or the Internet for too many hours a day to outright addiction. Addiction is manifested in such activities as compulsive Internet shopping or gaming, or constantly checking Facebook, and results in withdrawal symptoms – mental and physical pain – when an individual tries to stop (Young 1998). In addition, other daily activities – work, school, sleep, exercise and eating – are impeded. Clearly, young people and those frequently using computers for work, education or leisure are liable to show excessive use. This is the flipside of being included in the digital world.

Almost every research project concerning excessive use focuses on adolescents and young adults, who are most likely to take advantage of social-networking sites (SNS), messaging services and computer games. Excessive use of SNS is more of a problem for girls, while boys tend to play games too much (van Beuningen and Kloosterman 2018; Anderson et al. 2017). Excessive digital or social media use leads to a lack of concentration, e.g. at school and at work, as well as lack of sleep and face-to-face communication. In the Netherlands, 13 per cent of female Internet users consider themselves to be addicted to social media as compared to 7 per cent of males, though percentages among young people are generally higher (van Beuningen and Kloosterman 2018). However, as older generations make more use of SNS, messaging services and gaming, they too will exhibit such problems.

Excessive use is related more to mental characteristics and disorders such as (social) anxiety, depression and ADHD than to social characteristics of class, age and gender (Anderson et al. 2017). While particular users are more likely to be at risk in particular activities (SNS, chatting, gaming, gambling, etc.), some of them might also be better at coping with the problems. People with superior content-related digital skills, especially information, communication and strategic skills, and those with good social and parental relationships are more capable of reducing excessive use.

A related negative outcome is the problem of information or communication overload. Many people are overwhelmed by the amount and complexity of sources and messages on the Internet. In 2016, 20 per cent of American Internet users experienced information overload. Females, people above the age of fifty, and those with low incomes and an educational level of high school or less perceived significantly more information overload. They also had more trouble in coping with this problem (Horrigan 2016). Although there are no supporting data, it would seem most likely that individuals with good information, communication and strategic digital skills are better at handling these problems.

Cybercrime and abuse

It is possible for any Internet user to suffer from intrusion (hacking) and be a victim of computer identity theft (username and password). However, people with higher incomes and more property are also more likely to suffer from financial fraud or theft. However, the great majority of Internet users in the developed countries are now adopting Internet banking. In general, those with low education and incomes lack both the financial expertise and the digital skills (see chapter 5) to cope with such cybercrime.

The young users of social media and messaging services are more likely to encounter a number of other negative outcomes: bullying, unwanted sexting, harassment and provocation such as hate speech. While, in 2017, 41 per cent of Americans experienced some kind of Internet harassment (e.g. offensive name-calling, physical threats, racist comments, stalking and sexual harassment), younger people (aged eighteen to twenty-nine) suffered more than older generations (Duggan 2017). All kinds of harassment, with the exception of sexual harassment (Pew Id.), are more likely to be experienced by males than females. Neither social class nor education level were analysed in this Pew report.

A negative outcome that is receiving more attention of late is coming across disinformation on the Internet. This problem is encountered most by active information seekers. According to a survey published by the Pew Research Center, more than a third of American Internet users are engaged information seekers. Some of them are confident in using the Internet while others are eager to master its use better; they have much trust in particular information sources online (Olmstead and Smith 2017a). This section of the population is relatively young; the confident users have a high level of education and those eager to learn have a lower education and consist more of females than males. Other American users, those comparatively older – close to 50 per cent of the population – are wary about finding information online. They do not have much trust in information or news sources and have relatively low levels of information skills. They therefore will not recognize, or cannot cope with, disinformation when they come across it.

Coping with disinformation depends on trust in Internet sources and on one’s information, communication and strategic digital skills. Only having sufficient skills will enable users to know whether or not to have confidence in a particular website. The same people who are confronted with (dis) information online, usually people with high levels of education, have more of these skills.

Loss of security and privacy

The more people use the Internet, the more they may be confronted with a loss of security, be it from hacking, data theft, or receiving viruses or malware. The same goes for loss of privacy through abuse of personal data or whereabouts. The knowledge and skills needed to prevent or repair such losses are unequally distributed. According to another survey published by the Pew Research Center, American Internet users were able to answer fewer than half the number of elementary questions asked about cybersecurity. Knowledge about such matters appeared to be much better among people with higher education and somewhat better among younger users (Olmstead and Smith 2017b).

The practice of preventing or repairing loss of security and privacy varies among people of different education and age. Those with higher education installed anti-virus programs, firewalls, automatic updates, spam-filters, pop-up blockers and anti-spyware more often than people with lower education. They also changed passwords more often and looked carefully at the addresses of e-mails they received (van Deursen and van Dijk 2012; Büchi et al. 2016).

The evidence pertaining to age and security or privacy is mixed. In 2011–12, van Deursen and van Dijk observed in Dutch surveys that the young (those aged sixteen to thirty-five) installed such protection less than older users. Users below the age of forty also tended to manage their privacy settings on Facebook less well (van den Broeck et al. 2015). However, in a Swiss survey, Büchi et al. (2016) found that older Internet users showed lower levels of privacy protection, mainly through a lack of ‘Internet skills’.

What are the main conclusions about these negative outcomes of digital media use and the digital divide? Clearly, those who have access and the most frequent and varied use encounter these risks much more than others. However, many of them, especially the higher educated and the young, are also more competent in coping with them on account of having more Internet experience and better digital skills.

The balance sheet

We have seen that those on the right side of the digital divide of motivation, access, skills and usage are the ones who benefit more from the positive outcomes of digital media use in almost every domain. These are people with higher education and income, the young and, where particular applications are concerned, males. However, in some domains the situation is different: older users benefit more in political and personal domains (adult education and health applications); people with lower education and income benefit at least equally from SNSs in the social domain; and females benefit somewhat more from SNSs and personal development or health applications.

The flipside is that those on the right side of the digital divide are also the ones who have greater chance of encountering the negative outcomes of digital media. But, because they are generally more able to cope with the risks on account of having better digital skills, the result of experiencing negative outcomes is mixed.

The process of appropriation of digital media, as discussed in chapters 3 to 6, follows the model shown in figure 7.1 (see p. 97). Benefiting from positive outcomes feeds back to all resources. On the other hand, encountering and not coping sufficiently with the negative outcomes of digital media use reduces people’s resources. For example, excessive use harms both one’s mental resources (addiction, stress, overload, etc.) and one’s social resources (less physical contact). People may lose money through cybercrime (material resources), be confronted with abuse (harassment and bullying) leading to loss of self-confidence, trust and status (mental, social and cultural resources). Digital skills and social or parental support are required to prevent such damage, but these are also unequally divided in society.