6

Usage Inequality

Introduction: who frequently and variously uses digital media?

Now we have reached the last phase in the process of full adoption of digital media. The goal is to use these media for a particular purpose of information, communication, transaction or entertainment. Accomplishing the three former phases is a necessary condition for usage: without sufficient motivation and at least a minimal positive attitude, without achieving physical access, and without developing sufficient digital skills, any digital media use will be absent or marginal.

However, these conditions are not sufficient for actual usage. For example, people may have access to digital media in their household or on other places but never use them. They might be forced to use them without any imagination. They might have particular digital skills but not exploit them because they prefer traditional media or find no occasion to use digital media. Unfortunately, in statistics about Internet and computer usage, physical access – for instance in households – often is conflated with use. Usage has its own grounds that will be discussed in this chapter.

Usage of digital media is affected by the occasion, the obligation, the available time and the necessary effort expended. It depends on the tasks people have and the contexts in which they are living. In the last two decades the tasks have multiplied and the contexts now embrace all spheres of daily life. Because the nature of the contexts is different – social, economic, cultural and technological – the aspects of digital media usage to be discussed in this chapter are different too.

The chapter will start with the basic concepts of usage, for which several typologies have been created. The most important are the frequency and amount of use, use diversity and the activity of use (creation or consumption).

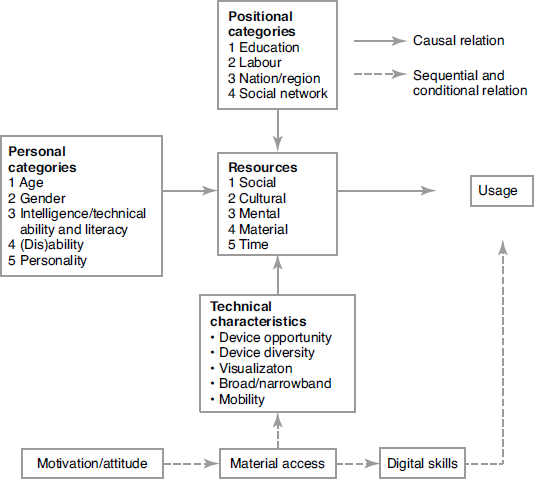

The second section will list the causes of frequency, diversity and the activity of use of digital media, including the new devices of the Internet of Things and augmented or virtual reality. The core section of this chapter, as in the previous chapters, follows the general model of resources and appropriation theory (resources, positional or personal categories, and the technical properties of the media).

I shall then examine the consequences for (in)equality of all the divides of usage observed in the previous section. Will they disappear when the diffusion of digital media in society is absolute and universal access has been achieved? Or will they persist and become a permanent characteristic of future societies?

The final section will discuss the evolution of the usage divides. This is not only about their disappearance or persistence but also about their nature. Will they be generational (age), cultural (gender, ethnicity and lifestyle), social (social class and status), educational (knowledge, intelligence and competency) or economic (employment or own business and career)?

Basic concepts

Use typologies

How can the extreme variation in Internet use be conceptualized and classified? There are two popular approaches: one is to derive a typology from the core concepts of a theory and the other is a description induced by factor or cluster analysis. Both approaches produce suitable typologies and classifications. The usual theoretical approach is one of the technology acceptance theories (see chapter 2). The uses and gratification theory (Katz et al. 1973; Flanagin and Metzger 2001) lists a number of needs, motivations and gratifications that lead to a typology of Internet or other digital media use (see table 3.2, p. 37, where the items in the column of specific gratifications look like a number of digital media or Internet applications). The technology acceptance theory (Davis 1989), however, has not yet produced a use typology. Finally, the social cognitive theory, among others creating a media attendance model (LaRose and Eastin 2004), offers a number of expected outcomes, such as monetary, novelty, social and status outcomes, which look like particular applications.

The resources and appropriation theory, used as a framework to present digital divide research in this book, has also not produced a user typology because this theory focuses on independent causes rather than dependent applications of use.

In order to find a neutral typology of digital media and Internet use, the second approach is better. Here the point of departure is observable activities, not motivations, perceptions or expected outcomes. Livingstone and Helsper (2007), Brandtzæg (2010), Blank and Groselj (2014) and van Deursen and van Dijk (2014a) were among the first to induce these typologies. However, Kalmus et al. (2011: 392) derived the most suitable typology from a factor analysis in a representative survey among the population of Estonia – a country known for its high Internet access and use. This typology inspired the list of activities shown in table 6.1. It can be extended with activities found in other surveys.

Table 6.1. Typology of Internet use domains, activities and applications

Source: Derived from Kalmus et al. (2011).

| Use domains | Activities | Internet applications |

| Work, study/ | Work | Professional applications |

| information use | Consumption | E-shopping and marketplaces |

| Finance | Internet banking | |

| Citizenship | E-government services | |

| Learning/study | Online courses and training | |

| Career development | Personal development/independent learning sources | |

| Searching for | Search engines/personal assistants and | |

| information | encyclopaedias | |

| Searching for news | News services/blogs | |

| Leisure/social use | Communicating | E-mail/messaging services |

| Networking | Social-networking services | |

| Community-building | Community sites and forums | |

| Sharing | Music, video (sharing) sites | |

| Entertainment | Online broadcasting and video | |

| Gaming | Online gaming | |

| Exploring | Browsing |

The most important distinction in the Kalmus typology and in table 6.1 is the dichotomy of the two main kinds of Internet domains: work/study or information and leisure or social use or activity. This distinction will become fairly important in the remainder of this chapter because unequal use of these domains will be shown to create structural divides.

Use indicators

How can we measure digital media use? There are three indicators often used in research (see also Blank and Groselj 2014):

- Frequency of use and amount of time: from a baseline of ‘non-use’, through ‘low use’, ‘regular use’ and ‘broad use’, the incidence and the number of hours during which people use the Internet, etc. (Reisdorf and Groselj 2017);

- Diversity of use: the number of different activities for which the Internet, etc., is used, for example as listed in table 6.1;

- Activity of use: creative (active) or consumptive (relatively passive).

The first two indicators will figure in the following sections about the causes and consequences of divides in digital media use. Unfortunately, the third will have to be largely ignored, as I have not found much data for this indicator.

Causes of divides in digital media use

Resources affecting digital media use

In discussing the inequalities observed in using digital media, I will follow the same concepts of the framework applied in the former chapters. The most significant causes are social and cultural resources, backed by sufficient material resources (income) and temporal resources (time), though mental resources are pertinent in the form of basic motivations (needs) and attitudes or beliefs in choosing particular applications of digital media. We will also see that personality and intelligence (cognitive and technical ability) affect digital media use.

The most important resources for digital media use are social; close to half of the Internet activities listed in table 6.1 can be called social. The social contexts in which people live may stimulate or reduce media activities (Selwyn 2003, Selwyn et al. 2006). People are often obliged in workplaces and schools to use particular digital media, and the network effect takes place in communities and families. Once there is a critical mass of users of a particular device, the rate of adoption creates further growth. This happened with e-mail, social-networking sites, messaging services and Internet access in general. The social context also determines the level of support people receive: those in dense social networks are more likely to use popular digital media than isolated or marginal members of society.

Cultural resources in the form of lifestyle affect digital media use. Some people work all day on a computer or smartphone, while others are involved in playing, gaming or gambling, continually watching YouTube videos and Netflix series, or perpetually chatting via messaging services. The use of digital media can also be inspired by the status acquired by sharing music and funny videos and pictures. While once the possession of a PC, an Internet connection or a mobile phone yielded status, today prestige is gained only by having the latest smartphone, a brand new app or game, a state of the art device for augmented or virtual reality, a very fast Internet connection, or a house fully equipped with advanced equipment.

Of course, mental resources in the form of positive motivations and attitudes continue to be relevant for frequency and type of digital media use. However, motivations and attitudes are not resources. The importance of such characteristics as personality, cognitive intelligence and technical ability, physical or mental disabilities, and literacy will be discussed below.

Material resources are needed to benefit from the incentives of the social context and the lifestyle, habits or hobbies and status aimed for. Companies or institutions need to invest sufficiently in the hardware, software and connections required for jobs where computers and the Internet would be advantageous. Similarly, if schools do not have adequate numbers of computers for students, and parents cannot afford to buy them for the home, the impetus will die. A ‘digital’ lifestyle and culture, together with status markers, might be attractive, but they are expensive to maintain.

Temporal resources are also required. Many hours are spent using computers and the Internet in workplaces and schools, depending on the type of job and study. Professionals may use them use them all day long, and individuals with flexible or temporary jobs need them more than those in permanent employment. Many people in the developed societies, particularly those unemployed or unable to work, spend much of their leisure time on the Internet.

Positional categories determining resources and digital media use

We now turn to the factors responsible for the inequality of the resources people have in using digital media. The overwhelming majority of surveys in digital divide research in the world show that the level of both education and employment, often correlated with the level of income, are the most important background factors for the frequency and variety of digital media use next to the positional categories of age and gender (see Ryan and Lewis 2017; Dutton and Reisdorf 2017; and Pew Research Center 2018 for the US; Blank and Groselj 2014; van Deursen and van Dijk 2014a; Reisdorf and Groselj 2017; Lindblom and Räsänen 2017; and Serrano-Cinca et al. 2018 for the UK and the EU; and Pew Research Center 2018 for the whole world). Research published by the Pew Center shows that levels of education make more of a difference in developing countries than in developed countries (Poushter et al. 2018: 12).

Those who gain a good education generally acquire a good job. Using digital media at school and then for homework extends both the frequency and the variety of use, including into leisure time, where more highly educated students use more information and career-related applications than those with less education (see below). Education level reinforces not only the social but also the cultural resources needed for digital media use. It increases the number and variety of social relationships for inspiration and support in the school environment and enhances a ‘digital lifestyle’ of heavy use, creating particular habits and status markers at home and elsewhere.

An individual’s labour position determines how frequently they use digital media, as well as how diverse that usage is and whether it is active or passive. Most research shows that it is managers and professionals who make greater use of computers than people with executive, manual and physical jobs (see Lindblom and Räsänen 2017 for the UK, Finland and Greece). Among managers and professionals, digital media are increasingly the primary – perhaps even the only – tools of their work; for administrative workers, however, perhaps practising data entry all day, their frequency of use will be very high but the diversity and creative use will be low. In general, the employed and students use more digital media than the retired and the unemployed (see examples in Blank and Groselj (2014) for the UK and Serrano-Cinca et al. (2018) for Spain), except for the unemployed in the Netherlands, who use the Internet more often for leisure pursuits (van Deursen and van Dijk 2014a).

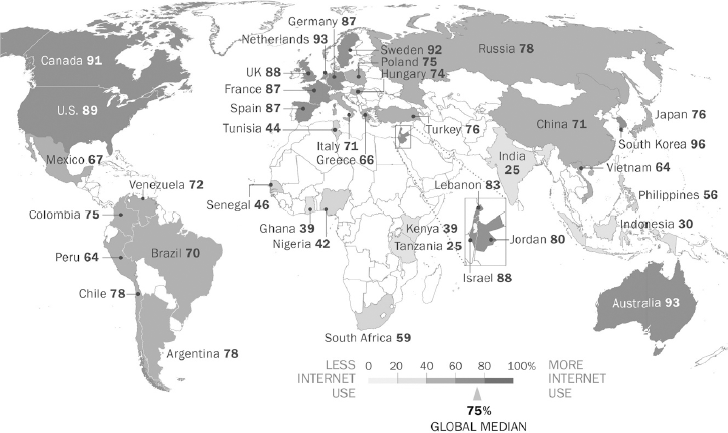

The third positional category affecting usage is in which country an individual lives in the world and whether they are in an urban or rural region. There is much inequality in the relevant infrastructure for access, as well as in the variety of digital media available, particularly between developed and developing countries. The distribution of Internet or smartphone users in the world was noted by researchers for the Pew Center in 2018 (see figure 6.1). The map shows that, of thirty-seven countries, North America, Europe and parts of the Asia-Pacific region have the most users and sub-Saharan Africa, India and Indonesia the fewest. The distribution corresponds closely with the general, economic (GDP), social inequality (Gini coefficient) and other levels of development often used as the positional categorization of these countries (World Bank 2016).

All nations reveal a significant internal divide in digital media use between urban and rural regions. Here the causes are the availability and quality of infrastructure, regional economic performance and poverty, levels of education and skills, and the preferences of local cultures (Salemink et al. 2017). In developing countries, even those who have a high level of education, occupation and income show lower use of digital media than people in developed countries in equivalent circumstances.

Figure 6.1. Percentages of adult Internet users or owners of a smartphone in thirty-seven countries of the world, 2017

Source: Poushter et al. (2018: 5).

A position in a social network will possibly affect digital media use too. However, I have found no empirical evidence of people having a central position in a large social network using digital media more than those with a small social network or in a marginal position. Both Tilly (2009) and Kadushin (2012) expect that the former find and hoard more opportunities – social media, messaging services and other online communication tools – than the latter. In earlier chapters I argued that social-network positions influence people’s motivation, assistance in gaining physical access, and support in developing digital skills. Network analyses and surveys are required to show these differences.

Household position is less important, since both frequency and variety of digital media use are at about the same level in both single-person and multi-person households; only the type of applications might be different (see Blank and Grosjelj 2014 for the UK).

Personal categories determining resources and digital media use

Almost every research project concerning the digital divide shows that age is the most important personal cause of different use after the level of education attained. While 48 per cent of the total world population used the Internet in 2017, 70.6 per cent of that usage was by people aged fifteen to twenty-four. The percentage gap between overall usage and that of the younger population was the smallest in Europe (79.6 versus 95.7 per cent) and the biggest in Africa (21.8 versus 40.3 per cent). The poorer the country, the wider the gap; it is widest in the so-called least developed countries (LDCs) (ITU 2017).

Age can be categorized by number of years, by generation and by life-stage. The most popular and questionable category is that of generation, where a distinction is made between the Digital Natives and Immigrants. Digital Natives were born and grew up after the advent of the World Wide Web (1993), a generation also called the ‘post-millennials’, born from 1997 onwards. The distinction was coined by Prensky (2001) and Tapscott (1998), who suggested that members of this generation were not only much more frequent users of digital media than previous generations but also better in terms of their skills, the variety of their use and multitasking with other activities. This proposition was later supported by research undertaken, among others, by Zickuhr (2011) and Rosen (2012). However, it was also sincerely criticized in the research of Buckingham (2008), Hargittai and Hinnant (2008) and Helsper and Eynon (2010), who attempted to show that other factors, such as Internet experience, digital skills and types of use, were more important than generational effects. There are enormous differences in access, skills and usage among the so-called Digital Natives (Hargittai and Hinnant 2008), while older generations may well have better content-related digital skills than the young generation, who are certainly more adept at medium-related skills (van Deursen 2010; van Deursen and van Dijk 2014a; see chapter 5).

The distinction between generation and life-stage is decisive. Chesley and Johnson (2014) have analysed the differential use of digital media by generation and during the life course. They argue that we use digital media differently in childhood, adolescence, young adulthood, older adulthood and old age, and they also show that the generational effect is important. The age at which we are first introduced to digital media has consequences for the way in which we use it for the rest of our life.

This distinction is important because the generational effect in usage will slowly be reduced as time passes. At this point the older generations in the developed countries are catching up fast. However, life-stage effects are here to stay. Even fifty years from now adolescents will use digital media to help form their identity and communicate with their peers. Adults will use them primarily for organizing their lives, while elderly people will use them mostly for leisure, services such as health care, and communication with family and friends.

The second personal category affecting digital media use is gender. In the 1980s and 1990s it was (young) males who were the first to use digital media (van Dijk 2005). After the year 2000 the gender gaps in frequency of use became smaller, and by 2017 it had been reduced worldwide to 11.6 per cent (less for females). However, in Africa it was still 25.3 per cent and in the LDCs as a whole 32.9 per cent, though in the Americas women already used the Internet 2.6 per cent more than men (ITU 2017). The final figure shows that the gender gap is a direct result of the unfavourable conditions for women in several countries with respect to employment, education and income (Hilbert 2011; ITU 2017); in all countries where women participate in higher education, the gap in the frequency and variety of use disappears.

This does not mean that the differences in the types of use, such as particular Internet applications – see table 6.1, p. 82 – are declining (see Jackson et al. 2001; Schumacher and Morahan-Martin 2001; Zillien and Hargittai 2009; Blank and Groselj 2014; van Deursen and van Dijk 2014a; Martínez-Cantos 2017; and Sultana and Imtiaz 2018). The common denominator is that females are more likely to use communication and commercial applications and males information and entertainment applications (see the leisure or social use versus the work and information applications in table 6.1). However, in the future, when all social and cultural distinctions in society will be fully reflected in digital media use, these differences may be more clearly pronounced. See the arguments below and the following chapters.

The third important set of personal categories effecting digital media use consists of intelligence, technical ability, literacy, and intellectual or physical disability. Although we have insufficient empirical evidence to back up the assertion, people of low intelligence (superficially and perhaps arbitrarily measured as IQ), those who have little technical ability or expertise, the functionally illiterate and the disabled make less use of digital media and the Internet. Surveys dealing with digital media use have no questions as to IQ or other measures of intelligence or the ability of respondents, and performance tests do not examine intelligence by other measures. Correlations are established only with the level of education attained.

Nevertheless, I want to argue that intelligence, technical ability, literacy and disability are very important background measures of mental, social and cultural resources causing the divides of digital media use. The main reasons for such people finding digital media less attractive are the design, the interface and the content of websites, which are designed for intelligent and literate people who are able to operate a device and its applications and have no disabilities.

It is estimated that 2.2 per cent of the population in Western countries have an IQ below 70; 13.6 per cent are between 70 and 85, and two-thirds of the population are at the average quotient, between 85 and 115 (Urbina 2011; and Flanagan and Harrison 2012). Chadwick et al. (2013) discuss the barriers and the opportunities of the Internet for the learning disabled and those of low intelligence. Many such individuals who have Internet access in their home do not actually use it (see Gutiérrez and Martorell 2011 for Spain), largely on account of the design and content of websites (Wehmeyer 2004). The learning disabled are often ‘infantilized’ by their caregivers, who think that the Internet is bad or dangerous for them (Chadwick et al. 2013).

In the least-developed countries, more than 50 per cent of the population are illiterate (UNDP 2016), and as much as 20 per cent of the population in the US (32 million adults) and the UK (8 million) may be functionally illiterate, with comparable figures in other Western countries (see Ullah and Ullah 2014; UNDP 2016). Such people are only able to understand images or symbols and video or audio content.

Another large category is the disabled, who are estimated as being between 12 and 27 per cent of any population (Fox 2011; Anderson and Perrin). For example, in the US, 15 per cent of the adult population have problems in walking, 9 per cent in hearing and 7 per cent in seeing; 11 per cent have a serious condition affecting their ability to concentrate, remember or make decisions, and 9 per cent are unable to go shopping or visit the doctor without assistance. While in 2016 only 8 per cent of Americans had never used the Internet, 23 per cent of disabled Americans had never done so. In that year only 50 per cent of disabled Americans use the Internet on a daily basis while the overall population reported 79 per cent daily use (Anderson and Perrin 2017). According to a large-scale survey of 3,556 disabled individuals in Poland in 2013, only 33 per cent used the Internet, while the figure for the whole population was 63 per cent (Duplaga 2017). Even controlled for age, poverty and education, disability remains as a digital divide factor (Dobransky and Hargittai 2016; Anderson and Perrin 2017).

The last personal category to be mentioned is personality. Several studies suggest that, among the ‘Big Five’ personal characteristics, people with particular traits show more Internet engagement than others (Russo and Amnå 2016). The first, openness to experience (showing intellectual curiosity for a breadth of cultural phenomena, novel experiences and new ideas), inspires more Internet use than the more closed-minded, pragmatic, habitual or perseverant personality (Tuten and Bosnjak 2001; Vecchione and Caprara 2009; Gerber et al. 2011). Second, extroversion also inspires Internet use, especially for establishing contacts and partaking in discussions such as in social networking and using social media in general (Ryan and Xenos 2011). Third, the conscientious personality, who is organized, reliable and structured, generally has a problem with the unstructured environment of large parts of the Internet (Landers and Lounsbury 2006), especially social-networking sites (Ryan and Xenos 2011). Agreeable personalities, those who are cooperative and trustful, are also found to be negative towards Internet use (Launders and Lounsbury 2006). Such individuals prefer face-to-face contact rather than the often antagonistic and conflictual relations in online discussion and networking. Finally, the evidence concerning neurotic personalities is mixed (Russo and Amnå 2016). Some researchers see that neuroticism hampers Internet use (Cullen and Morse 2011, observing online communities), while others note that it supports it (Correa et al. 2010, observing social media use).

In conclusion, openness to experience and extroversion certainly stimulate Internet use. Russo and Amnå (2016) conclude that, in the case of political communication, these traits support online political engagement.

We are now close to the end of the long list of causes of divides in digital media use, which are summarized in figure 6.2. The sequence of factors, apart from those pertaining to technical characteristics, is estimated. The remaining causes are a number of technical characteristics. Next to those affecting physical or material access and digital skills, there are also technical characteristics that influence the frequency, variety and type of digital media use.

Technical characteristics

A number of technical characteristics of contemporary digital media influence the resources people need to use these media. What are these characteristics? In the chapter on physical access we mentioned diversity. Some people have several different types of digital media while others may have only one device. In addition, devices have different potential usages, though the divide is mainly between smartphones or tablets on the one hand and desktops or laptops on the other. The former are not a full substitute for the latter. Smartphones and tablets have less memory, storage capacity and speed (Akiyoshi and Ono 2008; Mossberger et al. 2012; Napoli and Obar 2014) as well as a limited content availability (Napoli and Obar 2014), but they do offer more mobility (see below) and convenience and are cheaper in price. Smartphones, therefore, are frequently used for communication and entertainment (social networking and gaming) and when travelling, while desktops and laptops are often employed for information, education, business and work (Zillien and Hargittai 2009; Pearce and Rice 2013; Murphy et al. 2016). Thus people who own all these devices exhibit the most frequent and various digital media use. Van Deursen and van Dijk (2019) found in a representative survey in the Netherlands in 2018 that owning a greater range of devices is significantly related to a higher diversity of Internet use and a greater variety of outcomes.

Figure 6.2. Causal and sequential model of divides in digital media use

A logical subsequent characteristic is device opportunity. Some devices offer wider opportunities for a more satisfying and diverse Internet experience (Donner et al. 2011). They can be combined with all kinds of peripheral equipment (van Deursen and van Dijk (2019); items can be printed, files can be scanned to be uploaded, large files can be saved on a hard drive, and larger screens can be added to multitask online and to show or present visuals. These functions are not possible with mobile devices. In the developed countries, many young people, some ethnic minorities, and those on low incomes tend to use just mobiles (Hargittai and Kim 2010; Tsetsi and Rains 2017), and this is the case for a large majority of Internet users in the developing countries. However, smartphones are not very satisfactory for information-intensive tasks such as online education, e-government and e-health services or for most professional applications. As a result some authors are already talking about a ‘mobile underclass’ and ‘second class netizens’ benefiting less from digital media (Napoli and Obar 2014, 2017; Mossberger et al. 2012).

A third technical characteristic is the availability of broadband as compared to narrowband Internet connections. Before broadband arrived in the 1990s, users had dial-up connections, which took a long time and were costly. With broadband they were liberated and motivated to spend more time on the Internet and for a growing number of applications. Today, some people prefer mobile connections to save the relative expense of broadband (Mossberger et al. 2012; Horrigan and Duggan 2015). In 2018, two-thirds of Americans had broadband at home while one in five had a smartphone only. Racial minorities, older adults, rural residents, and those with lower levels of education and income are less likely to have broadband service at home (Smith and Olmstead 2018).

The final characteristic affecting digital media use is the rise of media with primarily visual content. Social media such as YouTube, Instagram and Pinterest are becoming more and more popular. Television channels, video services and gaming are moving to the Internet. This trend favours those who are illiterate or intellectually disabled and stimulates people with low levels of education. However, because all complex tasks such as job applications use primarily text media, the divide between users with different levels of education is growing (for other reasons see below).

The consequences of divides in digital media use

Divides of digital media use and outcomes

The main consequence of the divides in digital media use is that the outcomes are also unequally distributed. In the next chapter we will see that this goes for both positive and negative outcomes. Those who are frequent and active users gain many benefits in the economic, social, cultural or political fields and in everyday living. They are also more capable when it comes to preventing negative outcomes such as cybercrime, bullying, insult or harassment, privacy infringement and loss of security.

The next general consequence is that all outcomes reinforce existing divides. Social resources will be strengthened, for example, by frequent, various and active social-networking use. Those who already enjoy social support will gain more, while the socially isolated will remain marginalized. Cultural resources – a conspicuous lifestyle, dispositions and status – are highlighted by active participation in digital culture. Mental resources will flourish in developing technical ability, cognitive and emotional intelligence, or digital literacy through frequent, various and skilful digital media use. Material resources may accumulate through good use of e-commerce, as products and services become cheaper. Employment can be found via online applications and professional networking. Finally, people will gain more temporal resources by means of efficient digital media use.

The usage gap

In the first decade of the twenty-first century, the age and gender distinctions were more pronounced in digital media use than social class and status (van Deursen and van Dijk 2014a). However, this is now changing rapidly, as we have seen that the older generations are catching up in Internet use. The same goes for gender and ethnic distinctions. In the meantime distinctions of social class or status, articulated primarily at the level of education and income, persist and tend to be increasingly important. This will be argued and demonstrated in the following chapters.

The term ‘usage gap’ was first used by van Dijk ([1999] 2012, 2000, 2004). Others described the phenomenon as the ‘knowledge gap for the Internet’ (Bonfadelli 2002), ‘differentiated use’ (DiMaggio at al. 2004), ‘status-specific types of Internet usage’ (Zillien and Hargittai 2009) or ‘engagement in different Internet activities’ (Pearce and Rice 2013). ‘Usage gap’ refers to a systematic use of the Internet for particular goals by people of higher social class (education, income and property) and status (social position and cultural resources) as compared to those of lower social class and status. The goals are advanced information, communication and education, work, business and capital-enhancing or career activities (higher social class) as opposed to simple information and communication (chatting or messaging), shopping and entertainment (lower social class).

The usage gap concept is inspired by the term knowledge gap, which was popular in the 1970s and 1980s. Tichenor et al. (1970: 159) stated that, ‘as the diffusion of mass media information in a social system increases, segments of the population with a higher socio-economic status tend to acquire this information at a faster rate than the lower status segments.’ However, the usage gap is broader and more consequential for society than the knowledge gap (which touches only on mental categories – learning – in using mass media), as it also refers to behaviour and activities in using the Internet and other digital media. The latter are multifunctional and are drawn on for all activities in society and daily life. The behavioural and systemic effects of the usage gap are much more important than the learning effects of the knowledge gap.

Since the year 2000 a usage gap in Internet activities has been demonstrated in a long series of studies. Van Dijk (2000: 177) predicted that the gap of simple and advanced types of political participation he observed among people of all classes and education levels will grow. Educated people contributed to online political discussion, became members of political organizations, ran as candidates and turned out to vote more often than those with lower levels of education, who tended only to sign online petitions and respond to Internet polls, and who didn’t necessarily bother to vote. Bonfadelli (2002) showed that educated people used the Internet more actively and that their use was more information oriented, whereas the less educated seemed to be interested particularly in the entertainment functions of the Internet. DiMaggio et al. (2004: 39) assumed that higherstatus users were more effective at converting access into information and information into occupational advantage or social influence than less privileged users. In the last ten years these observations have been confirmed by a growing number of studies, among them those by Hargittai and Hinnant (2008), Zillien and Hargittai (2009), Helsper and Galácz (2009), van Deursen and van Dijk (2014a), Pearce and Rice (2013), Buchi et al. (2016), Tsetsi and Rains (2017), Yates et al. (2015) and Yates and Lockley (2018).

The evolution of divides in digital media use

It is likely that the usage gap in social class and status will become wider in the future, while those of age, gender and ethnicity will become smaller but not disappear entirely; existing cultural preferences will most likely remain. This is because the gap is determined not only by socio-economic inequality but also by a cultural differentiation that is growing in postmodern society. Another reason for the expected growth of the gap in social class and status is the expected divide in digital and twenty-first-century skills, as discussed in chapter 5. People of higher social class and status have better skills in order to find advanced information and communication online for work, education and business than those of lower social class and status, who are more likely to explore consumption, communication and entertainment online.

Divides in digital media use are also the result of the general differentiation of social relationships, together with economic divisions of labour and culture in a postmodern network society. This increasingly individualized society consists of a large number of communities, organizations, cultures and ethnicities with different lifestyles and social or cultural preferences. The greater the diffusion of digital media in society and daily life, the more their use will vary. However, this is a general trend and not as specific as the usage gap of class and culture.