3

Motivation and Attitude

Introduction: who wants digital media and feels fine about them?

The nature of the first stage of access to and adoption of digital media is psychological. Human needs, motives, attitudes, expectancies, gratifications and intentions drive the decision to purchase a computer or other digital medium and to connect to a network such as the Internet. The following stages are also driven primarily by the general motivation to engage (or not) with the digital world. Without sufficient motivation and a positive attitude, individuals will not develop digital skills or competencies. Similarly, they will not use digital media very often – only perhaps for one or two purposes. Finally, the outcomes of digital media use will be disappointing for those with low motivation and a negative attitude.

The following section deals with basic concepts. There is an abundance of psychological concepts in the literature concerning motivation. How are these related to each other? What are the most important needs, motives, gratifications, attitudes and expectancies to use or, indeed, not to use digital technology?

The third section is about the causes of different motivation. These are not only personal (age, gender, personality and the like) but also positional, partly societal characteristics. Those in gainful employment and students might well have more motivation to use digital technology than the unemployed. Those who are part of a social network where everybody uses digital media are also likely to be motivated. People living in developed and technologically advanced countries are assumed to be more motivated than people in developing, less technologically advanced countries. People with these personal and positional characteristics have resources that partly determine motivation and attitude for access and for use. These resources are not only of a mental kind. They might also be material, social, cultural and temporal resources.

The next section discusses the consequences of motivation and attitudes. Since different people purchase different quantities of hardware, software and services, they will develop different levels of digital skills, and the frequency and variety of their use of digital media will be different. Finally, the benefits they attain will be different. So, the digital divide will become wider with a lack of motivation in all phases of access.

The final section will describe the evolution of the level of motivation and attitudes towards digital technology. In the 1980s, even in the developed, technologically advanced countries, the majority of the population was apprehensive about the advent of the digital age. When the use of computers, the Internet and mobile telephony spread in the 1990s, motivation and positive attitudes increased considerably. Currently, close to 90 per cent of the population in the developed countries are motivated to use computers and the Internet (van Deursen and van Dijk 2012; van Deursen 2018). Even people in their eighties want to learn to use computers and the Internet, if only to e-mail and chat with their grandchildren. Nevertheless, we observe that computer anxiety and technophobia remain even in developed high-tech countries and that the motivation of those in developing countries is still lagging behind. See the emphasis on the perceived lack of relevance of digital applications in these countries (ITU 2017; Economist Intelligence Unit 2019). Evolution also means that the range between people who are complete non-users of the Internet, at one end of the spectrum, those who are low-frequency users, and those, at the other end, who are high-frequency users, online for perhaps more than twelve hours a day, is becoming wider in every part of the world.

Basic concepts

People’s reasons for use and non-use of digital media expressed in surveys can be conceptualized differently in psychological terms. Positive reasons can be framed in intentions (before) and gratifications (after) using specific applications. Negative reasons are mostly given by non-users and ex-users and are of a more general kind. The reasons for non-use listed in table 3.1 can be understood as explicit needs, motives, attitudes or expectations, though they may hide some implicit reasons. Someone who says that they don’t want a computer or smartphone might not genuinely like such tools, but it may be that they are not able to afford them or do not know how to work them.

The negative reasons found in surveys and listed in an average order of frequency in table 3.1 have remained much the same over the years. In rich countries the affordability explanation may have declined over time, but it still exists. Rejection of digital media was high in the 1980s and lower at the time of the Internet hype around the millennium. However, it recently began to increase again when many negative uses of the Internet and social media were reported. The most surprising thing is that the reasons for rejecting digital media are the same today as they were fifteen years ago; compare the lists of surveys in several countries in van Dijk (2005: 29–30), Reisdorf and Groselj (2017), Helsper and Reisdorf (2017), World Bank (2016) and Digital Inclusion Research Group (2017).

Table 3.1. Reasons for the non-use of computers and the Internet over time

Source: Summary of many international surveys.

| Order of importance | Reason |

| 1 | I do not want it (not interested). |

| 2 | I do not need it (not useful). |

| 3 | I reject the medium (cybercrime, Internet addiction, unreliable information, poor communication and others). |

| 4 | I have no computer or Internet connection. |

| 5 | I do not know how to use it; it is too complicated. |

| 6 | It is too expensive. |

| 7 | I have no time/I am too busy. |

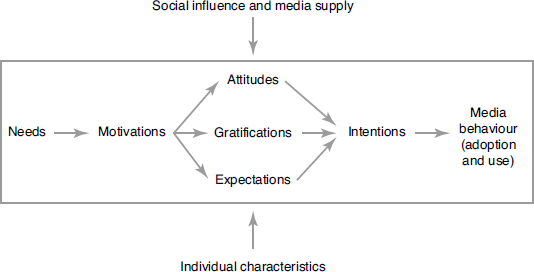

The distinction between the basic psychological concepts of needs, motivations, gratifications, attitudes and expectancies is insufficiently made in digital divide research. Figure 3.1 shows the series of psychological factors behind media behaviour. The first concepts or factors in this model derive from uses and gratification theory (see chapter 2). Needs are basic drives, motivations are conscious intentions, and gratifications come from satisfying rational and emotional goals. Needs are requirements for survival. Maslow (1943), for example, lists basic needs ranging from physical needs (food, water and sex) and safety to those of love/belonging, esteem and selfactualization. While digital media cannot at present be said to fall into the category of basic needs, in the future almost every job might require ICTs and online dating may become dominant. Currently, it is primarily the ‘higher’ needs of identity, communication, sociality and status that are met by the use of digital media.

Figure 3.1. A sequential model of psychological factors behind media behaviour

While needs can be partly unconscious, the motivations derived from these needs are always conscious. A single reason to act might be a motive, and motivation often involves several motives. For example, the use of social media and online gaming might be motivated by such reasons as socializing, learning, the wish for personal development, or just passing time.

Gratifications are the desired results of a goal-oriented act – the fulfilment of one or more motives. When the goal is reached and also creates a positive emotion, such as pleasure, it will be repeated. When goals are not reached and negative emotions occur, gratifications will no longer be sought.

In the literature we find many lists of needs, motivations and gratifications for the adoption and use of digital media. For example, in the perspective of uses and gratification theory, Katz et al. (1973) identified the needs of traditional media; Cho et al. (2003) transformed these for digital media. Papacharissi and Rubin (2000) enumerated the motivations and Sundar and Limperos (2013) and Dhir et al. (2016) list gratifications for specific new media. These are summarized in table 3.2. The right-hand column of the table gives a number of gratifications that are recognized as important goals, especially of using the Internet, while the other two columns give the background needs and motives of these goals. (Gratifications are not concrete applications such as using social-networking sites, which are discussed in chapter 6, ‘Usage’.)

Table 3.2. Needs, motives and gratifications in seeking and using digital media/the Internet

| Needs | Motives | Gratifications |

| Material/practical | Managing daily life | – Coordination – Utility/shop – Convenience |

| Cognitive | Learning | – Information seeking – Novelty/news |

| Affective | Feeling | – Excitement/arousal – Self-assurance |

| Personal | Personal development | – Identity creation – Status gain |

| Social | Socializing | – Social connection – Social interaction – Finding other opinions |

| Escape/play | Passing time | – Entertainment – Gaming – Consuming |

Needs, motives and gratifications are not the only psychological factors affecting intentions to adopt and use digital media (see figure 3.1.). The theory of planned behaviour and the technology acceptance model focus on perceptions and attitudes. Attitudes may be cognitive (knowledge about digital media), emotional (experiences or feelings) or normative (judgements). They may also be general (liking or not liking technology) or specific (liking or not liking a particular technology/medium). General attitudes vary from technophilia and computer mania to technophobia and computer anxiety (see below). Specific attitudes may be positive or negative. For example, at the time of the Internet hype around the year 2000, positive attitudes were dominant. Fifteen years later the downsides of Internet use became evident. Negative attitudes towards digital media are one of the most important causes for non-use and ex-use (van Dijk 2005; Reisdorf and Groselj 2017; Helsper and Reisdorf 2017).

Expectations are the hopes that using digital media will have particular outcomes and are based on knowledge and perhaps past experience of using these media. These are the basic concepts of social cognitive theory, discussed in chapter 2, which focuses on the experience and habits of people who have already used such media for some time. LaRose and Eastin (2004: 370) observed the following six expected outcomes of Internet use. With novel outcomes, people expect to find information or news. In activity outcomes they assume that they will be entertained – for example, by playing games. The third expectation is to find monetary outcomes – searching out cheap or free products and services or saving time by e-shopping. The fourth expectation contains self-reactive outcomes: these are benefits for the self, such as passing the time, relieving boredom or feeling less alone. The fifth expectation is gaining status: an individual might find others respect them because they are using the Internet. The final expectation is finding social outcomes, such as coming across friends and love partners or obtaining support from others. Following the rise of social media since 2004, the expectation of social outcomes has become the most important.

Intentions are mental states determining whether people wish to act or not. This is the last step before accepting and adopting or rejecting a technology (see figure 3.1). This decision can be blocked by external factors, for instance facilitating conditions. Someone who clearly wants to purchase a computer or find an Internet connection can be prevented from doing so because they have no money, while someone else might not want a computer and Internet connection but is obliged to accept and use them because their job or course of study requires them to do so.

Causes of differences in motivation

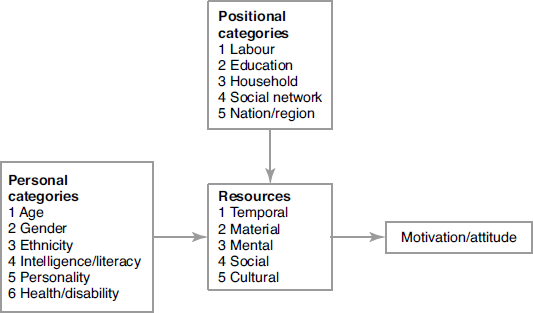

Having defined the basic general concepts of motivation and attitude concerning digital media, we are now looking for their causes. We will use the model shown in figure 2.3 (see p. 33), which is broad enough to contain all the relevant causes found in the literature. We will start with the resources important for the first stage of access (motivation and attitude), followed by the particular personal and positional categories of individuals.

Resources and motivation

Among the five resources to be discussed (temporal, material, mental, social and cultural), the first three – temporal, material and mental – are primary, while the other two – social and cultural – come to the fore when digital technology is fully incorporated in society.

To be motivated to use digital media, people must first have the time to do so. Positive conditions are having a job or being engaged in a course of a study in which you have to use technology for several hours a day; thus workers or students are motivated whether or not they actually like digital media. People with much free leisure time might also have motivation. To our surprise, we found in a nationwide survey in the Netherlands in 2011 that the unemployed and those unable to work were the most frequent Internet users (van Deursen and van Dijk 2014b), taking advantage of it for passing time, entertainment or finding a job.

Negative conditions arise of course when people are busy with other activities, such as housework or childcare, being engaged in manual labour, or being involved in sports. On the other hand, digital media in daily life may lead to an increase in positive stimuli and attitudes and a decrease in negative ones. The result may be that an excessive use of smartphones, computer games and Internet activities dominates and harms other activities and needs, such as sleeping, regular eating, face-to-face communication and physical exercise.

The second conditional resources are material and consist of income, property and appliances for the household, work or study. When people have fewer of these material resources, or simply cannot afford them, they will be less motivated towards their use. This is a major aspect in poor countries. However, in rich countries there is a substantial proportion of the population that can afford perhaps only one device and connection, while the wealthy may have access to several types of computers and connections.

Mental resources are capacities such as intelligence, technical ability and literacy rather than characteristics of motivation or attitude. People who have these capacities will be much more inclined to use digital technology. While intelligence is partly hereditary, technical ability and literacy are learned and improved in practice. People who are good at numbers, fluent in reading and writing and tech-savvy are much more motivated to use digital media than those who are illiterate, who cannot calculate and who lack the ability to use complicated devices.

Related to technical ability, people who lack self-confidence or who have neurotic personalities (see below) may show computer anxiety (Brosnan 1998; Chua et al. 1999; van Dijk 2005). This is a feeling of discomfort, stress or fear experienced when confronting computers, though it can also be caused by frustration arising from bad experiences. Another phenomenon is technophobia – fear of technology driven by a particular negative attitude or opinion. It is a rejection of the world of computers and a distrust about their positive outcomes. Today such fears are also about privacy and security, a loss of freedom through government control or corporate tracking and when confronted with disinformation.

The fourth type of conditional resources are social. Social relations and networks are crucial in learning and to support and motivate people to use digital media or to develop a positive attitude towards them. People with a wide social network are more likely to look for access to digital media than those who are isolated socially (van Deursen et al. 2014; Courtois and Verdegem 2016). For young people, relations with peers are the first trigger to gaining access to and mastering digital applications; the alternative is to become socially excluded. There is a certain status in, for example, uploading a video to YouTube or owning the latest new device or app, and this is extremely motivating in particular for the young. For older people, the social context and support of friends, family, colleagues and neighbours also is vital for motivation: in particular they participate in social media in order to communicate with family, friends and (grand) children.

Finally we come to cultural resources – cultural capital or goods as well as such properties as status and esteem. In the developed countries people live in a material environment of computerized workplaces and homes full of devices and screens and generally have a positive attitude towards using digital media. In developing countries such technology is often limited to universities, schools, hospitals, government departments, workplaces, libraries and Internet cafés, so people do not routinely come into contact with it.

Positional categories and motivation

There are five positional categories, the first of which is the labour position. The unemployed, people unable to work and many pensioners will have fewer resources and less motivation to use digital media, and perhaps negative attitudes as well. Those who are part of the workforce may have jobs that require computer skills, and so many unemployed people looking for a job have the motivation to learn such skills. However, all research indicates that individuals in higher occupations are the most motivated and in general have the most positive attitudes.

Similarly, twenty-five years of research have shown that people with higher education have both more resources and greater motivation and positive attitudes where using information and communication technology is concerned. The information aspect of digital media is particularly attractive for such individuals (van Dijk 2005, 2013), while the communication aspect is popular among all levels of society.

Being part of a family household also indicates a probability of being motivated to use digital media. In every country, households with the highest rate of computer possession and Internet access are those with school-age children. Single-person households have the lowest rates, especially among those with low levels of education. Larger families increase the efficiency and reduce the individual cost of using devices and connections.

Being part of a social network is also very relevant for the motivation and attitudes towards using digital media. The network helps in developing skills and locating attractive applications such as social media and phone apps. Being in a central position in a wide network is also more beneficial than being in an isolated or marginal position.

The last positional category is being an inhabitant of a particular nation or region. The average motivation and positive attitude among residents of rich and technologically advanced countries and for people in urban areas is obviously much stronger, as advanced countries and urban regions offer all the necessary infrastructure not only to motivate but also to use digital media. This is rarely the case in less advanced countries. For example, a university professor in Burundi has less chance of being motivated and less necessity to use digital media than a professor in Sweden.

Personal categories and motivation

The first personal category is age or generation. All research in this area shows that young people are more motivated and positively oriented towards digital media use than seniors. Young people are more inclined than older people to accept every new technology, but today’s young people have grown up with digital technology – they are digital natives. They cannot imagine a world without digital media, and it helps shape their identity. People over the age of forty, on the other hand, have had to adapt to the new technology, but when they manage to do so it may well become part of their everyday lives.

The second category is gender. Males were the first to be motivated to adopt digital technology, but females were quick to catch up, and in developed countries gender differences are becoming smaller and smaller. However, in countries with strong patriarchal cultures, both rich and poor, there remains a gender gap in motivation.

The third category is ethnicity. This is a sensitive category because it is often combined with race. In fact the differences in motivation and attitude among specific ethnic, migrant or native, majority or minority groups in a country are related more to economic deprivation, discrimination and cultural preferences than to race. Minority and migrant groups actually use digital media as tools to communicate with their home communities and for support in difficult situations. A survey in the United States showed that Asian Americans have the highest motivation to use digital media, more than Anglo-Americans and much more than African and Hispanic Americans (Perrin and Duggan 2015). However, this was related not to race but to socio-economic status and cultural or online preferences.

One of the reasons why the highly educated are more motivated to use digital media is their assumed cognitive intelligence. This is related not only to the individual’s level of education but also to the nature of information and communication technology, which addresses the capacity to process information. A related personal category is the level of literacy. Computer software requires a high level of literacy, so people who have a low level of literacy will have less motivation. The latter tend to use digital media for pictures, videos and music. In developing countries a large proportion of the population is illiterate, and even in developed countries perhaps 10 to 30 per cent is functionally illiterate. Such people have to rely on remembering which key strokes to use.

Another personal category often related to motivation to use digital media is personality. The evidence here is inconclusive (Russo and Amnå 2016). The influence of personality depends on the particular applications and technologies used. In the literature, the ‘Big Five’ dimensions of personality (openness to experience, extroversion, conscientiousness, agreeableness and neuroticism) are linked to computer and Internet use with applications such as social media. People having the trait of openness to experience (curiosity, appreciation of news and new ideas) like to explore the web (Tuten and Bosnjak 2001) and to find new and old relationships via social media (Correa et al. 2010).

Extroversion (assertiveness, sociability, liveliness and having positive emotions) used to be negatively related to Internet use because the web was assumed to be impersonal, while introverts liked the advantage of being able to protect their anonymity (Hamburger and Ben-Artzi 2000). However, it was found that extroverts were drawn to social media for its sociability and potential for expression (Ryan and Xenos 2011).

Conscientiousness (being organized, structured, reliable and dutiful) was observed to be positively related to the use of a computer because of its routine and reliable operations (Finn and Korukonda 2004). However, the Internet environment, especially the chaotic settings of social-networking sites, was found to be too unstructured for conscientious people (Landers and Lounsbury 2006). Agreeableness (being kind, considerate, likeable, prosocial and helpful towards others) was also negatively related to Internet use (ibid.), since such individuals prefer face-to-face communication. However, this might change with the development of social media.

Finally, neuroticism (feeling anxious, nervous and insecure) has been linked with computer anxiety (Hudiberg 1999; Chua et al. 1999) and the unsafe environment of the Internet (Tuten and Bosnjak 2001). Those with neurotic personalities have found more positive experiences in the relatively safe setting of social networks among existing friends (Correa et al. 2010).

The last personal category to be discussed is health or ability. It might be thought that disabled people would be highly motivated to use digital media to compensate for a handicap, especially if they have a mobility problem. However, their position in fact means that many disabled people are less motivated: on average only half of the disabled people in the world are in the workforce, and many are isolated socially (OECD 2010; WHO 2011). Other problems are that interfacing aids for the disabled are underdeveloped and that many organizations do not follow official web guidelines of accessibility for such individuals (Velleman 2018).

The causal argument is summarized in figure 3.2. The order of elements in the categories follows my own estimations observed from survey results.

Figure 3.2. Causal model of differences in motivation and attitude for access

The consequences of differences in motivation

Effects in other phases of digital media access

There are consequences for all subsequent phases in the process of acceptance of this technology of having more or less motivation to use digital media and having either positive or negative attitudes towards them (see the test of the model in figure 2.2 in van Deursen and van Dijk 2015b). The first is the decision to access the Internet: people have to weigh the cost of the purchase of a computer against the cost of everything else they need to buy. Less motivation and a negative attitude will also lead to less practice in developing advanced operational and content-related digital skills (see chapter 5). However, the biggest effect may be observed in the phase of usage (ibid.). Increasing motivation and maintaining positive attitudes lead to more frequency and variation of use in particular applications. People with high motivation tend to become frequent users of apps. The final consequence is whether or not people take advantage of the benefits of digital media (van Deursen et al. 2017). The higher the motivation, the more benefits, although negative effects may arise when too much use results in addiction and other excessive behaviour.

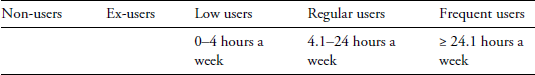

Table 3.3. Spectrum of Internet users: from non-users to frequent users, 2017

Shifts in the spectrum of Internet users

The level and change of motivation and attitudes towards digital media causes shifts in the spectrum of Internet users. This spectrum comprises at least five categories of Internet use (see table 3.3).

The motivations and attitudes of non-users were discussed at the beginning of this chapter (see table 3.1, p. 36). Lack of motivation and negative attitudes are major causes of non-use, especially in rich countries. Next to the have-nots we find the want-nots. Ex-users are the ‘dropouts’ of the Internet, temporary or permanent. About fifteen years ago in the US they formed perhaps 10 per cent of (former) Internet users (Katz and Rice 2002; Lenhart et al. 2003). Today, this figure may be less than 5 per cent. For example, in the UK in 2013 it was 3.5 per cent (Reisdorf and Groselj 2017). However, in poor and developing countries the figure may be higher. Structural causes of dropping out are becoming unemployed, getting divorced and becoming homeless, while individual causes include a growing negative attitude towards and dislike of the Internet or computers.

Low users in 2017 are people using the Internet for up to 4 hours a week and for relatively few online activities. In the UK in 2013 they accounted for 21 per cent of the population, while non-users comprised 18.1 per cent (Reisdorf and Groselj 2017). Low users generally have negative attitudes towards technologies and the Internet in general (ibid.: 1172). For those in the developed countries, motivation and attitude factors are probably more important than the usual demographics of deprivation mentioned in the literature (education, job, income, gender, age and social network). Regular users in 2017 are estimated to be online for 4.1 to 24 hours a week. In the developed countries this category accommodates the biggest proportion of the population. Frequent users today – the digital information elite of society – engage in Internet use for more than 24 hours each week. On average they are extremely motivated to use digital media, and they also enjoy the greatest benefits, as well as suffering from high workloads and excessive Internet use.

The evolution of motivation and attitudes

Three epochal shifts are occurring in the level and nature of motivation and attitudes towards the use of digital media. The most important is that positive motivations and attitudes are growing in the general population following the diffusion of digital media in society. Non-users become low users and low users tend to become regular or frequent users. In the 1980s and 1990s, when traditional media held sway, motivations to use digital media were low and attitudes were marked by negativity. Even in 2002 more than half of American and European non-users (roughly half of the population) declared in surveys that they did not plan to use the Internet (Lenhart et al. 2003; Katz and Rice 2002; Van Dijk 2005). But soon afterwards the mood changed and, increasingly, larger numbers of people were inspired to go online.

Today, I think it likely that more than 90 per cent of the populations of technologically advanced countries now make use of the Internet (see for instance the Dutch surveys of van Deursen and van Dijk 2012 and van Deursen 2018). It is becoming increasingly necessary to have access in order to function as a member of society in these countries. The populations in developing countries are probably still lagging behind. However, positive and negative attitudes are mixed worldwide because of the appearance of the detrimental effects of Internet use (see chapter 7).

The second shift in the level and nature of motivation and attitude is that the gaps between the various positions on the spectrum probably become wider. The frequency of use and amount of activity between non-users, ex-users and low users, at the one end, and regular and frequent users, at the other, is growing. While the latter develop greater motivation and more positive attitudes, non-users and low users remain at the same level.

The related third shift is that those on the right-hand side of the spectrum benefit more and more from the use of the digital media (see chapter 7), resulting in a feedback loop of greater motivation and more positive attitudes.