Our beliefs are like unquestioned commands, telling us how things are, what’s possible and impossible and what we can and cannot do. They shape every action, every thought, and every feeling that we experience. As a result, changing our belief systems is central to making any real and lasting change in our lives.

—TONY ROBBINS

“Do you have time right now?” the young monk asks me. “Let’s go talk.”

Did I have time? It was our last night in Fiji. We were sitting around a large table, enjoying one of the grandest meals I’ve ever seen. It was 2009 and my then business partner, Mike, and I were guests at a nine-day advanced meditation retreat at Namale, a magnificent resort owned by author and world-famous trainer Tony Robbins. Our group was an interesting assortment that included Hollywood actors, a stock market prodigy, and a former Miss America—plus the monks from India who led the retreat. I was honored that Tony and his wife had invited me to join this group and experience their beautiful island home.

It was a celebratory close to nine days of intensive self-exploration, during which we tried to truly understand ourselves and our potential. And on the final day, we were told we would have a private consultation with a monk who would give us a “revelation.”

For reasons I’ll never know, my monk decided to have his consultation with me in the middle of this sumptuous dinner, just after my third glass of wine.

But when your monk calls, you listen. “Where would you like to go?” I ask.

“Let’s go to the hot tub,” he says.

Naturally.

We go to the open-air hot tub under the starry Fijian sky. I climb in. He sits on the edge, dipping his feet into the water. He looks at me and says:

“You know what your problem is?

“No,” I respond, surprised and, to be honest, mildly annoyed, “What is my problem?

“You have low self-esteem.”

What the . . . ?

“I don’t think so,” I reply, as reasonably as I can, trying to hide my growing irritation. “I think I’m pretty confident. I run a business. I’m thrilled with my life—”

“No no no no no.” He cuts me off. “You have low self-esteem. This is the cause of all your problems. I’ve observed you. When you’re brainstorming with your partner and he shoots down one of your ideas, you get agitated and defensive. I bet you have issues with your wife, and I bet you have issues with others. You cannot take criticism. It’s all because of one thing: You have low self-esteem.”

It was like a smack in the face. The warm water in the hot tub no longer felt so comforting. The monk was dead-on. And after nine days of meditation and self-reflection, I was more open to this sort of insight, even if it was painful to hear.

I was overly defensive in brainstorming meetings, especially with my business partner. I did often feel hurt or misunderstood in family situations. But the real problem wasn’t that someone was shooting down my idea, not listening to me, or misunderstanding me. It all boiled down to a deeply buried belief that I, by myself, was not enough.

It was why I got defensive in meetings. I felt the dismissal of my ideas as a dismissal of me.

It’s why I became an entrepreneur. To prove I was worthy and enough.

It’s why I built the most beautiful office in my city. To prove I could do it.

It was why I became wealthy. To prove something.

I could see how this belief that I needed to prove that I was enough—this model of reality I’d held for so long—had driven me into the arms of success. But I could also see how the idea that I had to prove myself had caused great pain in my life. Was it possible that without this limiting belief, I might be even more successful in my work and relationships—without paying such a high personal price?

What might happen if I developed a belief that I was enough and had nothing to prove?

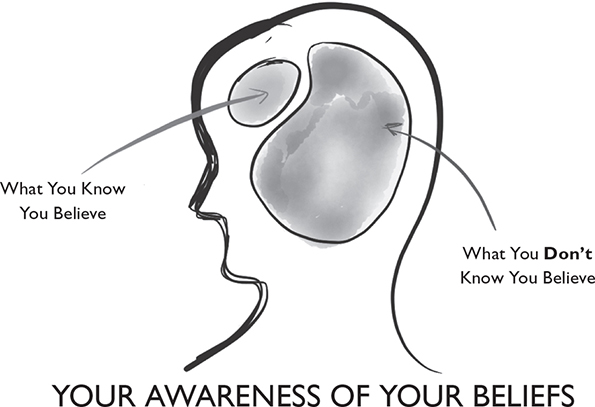

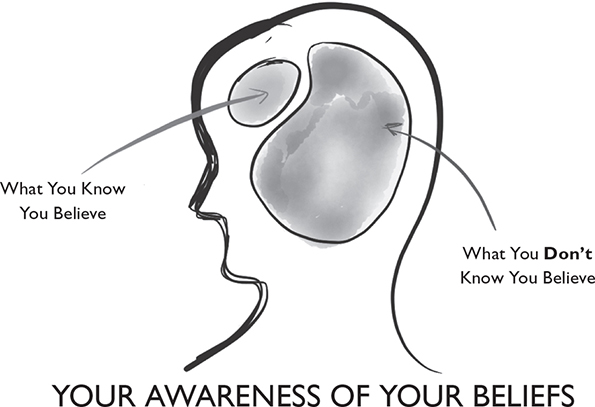

Our models of reality are often unknown to us. Some models we know we have. For example, I know I believe in the importance of having a calling, in the power of gratitude, and in being kind to the people I work with. But we also have models of reality embedded deep within that we’re mostly unaware of. What you know you believe is much smaller than what you don’t know you believe.

LESSON 1: Our models of reality lie below the surface. Often we do not realize we have them until some intervention or contemplative practice makes us aware.

Much of growing wiser and moving toward the extraordinary is really about becoming aware of the models of reality that you carry with you without realizing it.

I was unaware I had a belief that I was not enough. Identifying it and learning to resolve it made a huge impact on the quality of my life and how I behaved as a friend, colleague, and lover.

In this chapter we’ll explore how the world of our past infused us with certain beliefs—and how these beliefs now shape the world of our present and future. We’ll also explore how we can become more aware of our hidden models and then how to swap the unhealthy ones with updated models. The first step is to discover how we take on these models.

Where does this belief of “I am not enough” and other limiting models of reality come from? For most of us, they come from our childhood.

I grew up in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, but was of northern Indian origin, so I looked different from the other kids at my school, who were of Chinese or Southeast Asian origin. I had skin of a different color, a bigger nose, more body hair. It was tough being a minority kid. I was ridiculed and called names in elementary school, including Gorilla Boy because I had hair on my legs and Hook Nose because of my large Roman nose. As a result, I grew up believing I was different. I hated my long nose and my “gorilla” legs.

When I turned thirteen, my father enrolled me in a private school for expat children. Surrounded by diversity, with kids from some fifteen countries in my class, I felt somewhat normal. But adolescence had other challenges. I developed severe chronic acne that landed me in dermatologists’ offices, and I was on frequent acne medication by age sixteen. That earned me yet another name at school: Pimple Face. It got worse. By my teen years, my eyes had deteriorated to the point where I had to wear glasses with superthick lenses. They broke frequently, and I’d patch them with tape, making me a walking stereotype of the nerd with tape on his glasses. As you can imagine, teenage life for me was not particularly easy.

My negative beliefs about my appearance wrecked my confidence for the first decades of my life. I was socially awkward. I hardly went out with friends. I had crushes on girls but never had the guts to ask anyone out.

In college at the University of Michigan, I saw myself as the engineering geek, the guy girls might want as a friend but no one wanted to date. Thus I found myself at twenty-two, a college junior, never having had a girlfriend.

Then something changed. And it started with a kiss.

It happened at a college dance. I’d had one too many beers, which is probably the only reason I was dancing with the prettiest girl in the room. Her name was Mary. I’d known her for years and had always admired her, but she was way out of my league.

To this day I don’t know what came over me, but while we were dancing, I leaned in and kissed her. Immediately I pulled back, babbling something like, “I’m so sorry—I didn’t mean to do that.” I expected Mary to be offended.

Instead, she looked at me and said, “Are you kidding? You’re f**king hot.” Then the prettiest girl in the room grabbed me and locked her lips with mine. One thing led to another, and that ended up being one of the most amazing nights of my college life.

When a model of reality changes, the way you operate in the world changes, too. I woke the next day feeling as if I’d awakened in a whole new reality. If Mary, the prettiest girl in the room, thought I was hot, maybe I wasn’t so unattractive, and maybe other women could think so, too.

That single realization ended my belief that I was invisible to women. It radically transformed my ability to communicate with the opposite sex. Thanks to Mary, my dating life took off. Nothing about my appearance had changed. But armed with a new model of reality about my attractiveness, I suddenly seemed to be a magnet for female attention. It was amazing how a belief, when shifted, could create such a dramatic turnaround in my world.

Shortly thereafter, I met up with another beautiful woman, Kristina, whom I’d had a crush on for a long time. I’d known her for years as a friend and always considered her the dream woman. Beautiful, bold, highly intelligent. And a redhead. I loved redheads.

But this time, with my new model of reality, I approached Kristina differently. We started dating. Three years later, I proposed. Today, fifteen years later, we’re still together, with two wonderful kids.

Now I go on stage without feeling awkward. I go on camera without fearing how I look. All because one girl I had great admiration for helped me turn around a long-held model of reality. I had a lot more damaging beliefs to heal, but it was proof that with the right force, even entrenched childhood models of reality can be completely disrupted. And when it happens, the rewards can be amazing.

LESSON 2: We often carry disempowering models of reality that we inherited as far back as childhood.

In 2015 I had an experience that helped me knock down another model of reality that was having an incredibly limiting impact on my life: I could not hold onto money. My business was doing well, but I was extremely uncomfortable taking ownership of the financial gains. My festival-like event, A-Fest, for example, was profitable, but I was giving away 100 percent of the profits to good causes without actually keeping anything as a reward. I was the coauthor of several personal development courses, but I’d never negotiated for the higher royalty I felt I deserved. This detachment from material wealth wasn’t a totally bad thing. But I also felt it had a downside, as it could limit the growth of my businesses and projects.

In 2015 I was wrapping up another great A-Fest, a festival I had founded in 2010, this time in Dubrovnik, Croatia. The event had just ended, and hundreds of participants were heading home. Walking into the restaurant overlooking the Adriatic Sea, I saw hypnotherapist Marisa Peer and her husband, British entrepreneur John Davy, having breakfast.

Marisa is an extraordinary individual who has helped people with serious problems have profound breakthroughs in personal growth very quickly. Marisa is one of the most powerful transformers of human belief systems I had ever come across; her work and her results are legendary. She counts the British royal family and a Who’s Who list of Hollywood celebs among her clientele.

Marisa’s speech at that A-Fest had commanded a standing ovation and was voted the best presentation of the event. In her speech, Marisa explained that the biggest ailment afflicting human beings is the idea of “I am not enough.” This childhood belief carries well into adulthood and becomes the root cause of a lot of our problems.

As we had breakfast and discussed her work, I asked Marisa if she could hypnotize me. I’d never had hypnotherapy and was curious about the effects.

A few hours later, Marisa came to my hotel suite, and we talked about my goals for the session. My aim was this: I wanted to understand my attitude about money. I wondered if it connected with some models of reality I might need to get rid of.

Marisa guided me into a regression, sifting through memories and images from my life. I felt as if I was drifting off into a light nap as she guided me with her voice. “Go back to a moment in your past when you first developed this belief,” she said.

Suddenly, I saw Mr. John, a teacher I’d had as a teenager. I adored him, and he was an incredible teacher. But while everyone in the class liked him, we all felt sorry for him. He always seemed so lonely. We knew his wife had left him. We knew he lived in a small apartment and didn’t have much money. But we loved him; we spent a lot of time talking about what a great guy he was and what a shame it was that he was in that situation.

“Can you see a thought pattern that you may have developed from this moment?” Marisa asked. And I realized that the Brule I’d internalized was:

I saw myself as a teacher because I run an education company and speak and write on personal growth. And I had an unconscious belief that I had to suffer in order to be a great teacher—which in my case manifested as having to be broke.

But Marisa didn’t stop there. She made me regress to another moment. I saw myself in the back seat of my parents’ car. It was my birthday. I was maybe nine or ten. My parents were driving me to a store to buy me a birthday gift. I was pretending to be asleep, but I could hear them talking in a worried way about money. At the time my parents were not wealthy, but they had enough. My mom was a public school teacher and my dad was a small entrepreneur. I remembered a feeling of guilt washing over me about my birthday gift. At the store, I picked out a book. “That’s all?” my mom asked. “You can pick out something more.” So I picked up a hockey stick. She said, “It’s your birthday. You can have more.” But I didn’t want to burden my parents with any more expenses. That memory crystallized another model of reality I’d been carrying around:

We kept going. I regressed to another moment. I was sixteen, standing in the hot sun on a basketball court. The head of my school, a burly former weight lifter who, for whatever reason, seemed to despise me, even though I was a top student, was punishing me. That day, I’d forgotten my shorts for physical education class. He punished me for this small infraction by making me stand in the sun for two hours. Then, because I didn’t seem afraid, he amped up the punishment by phoning my father in front of me and saying to me, “You’re expelled from the school.” Then he walked away.

When my father arrived at the school, the headmaster told him, “I’m not really expelling your son. I’m just trying to scare him to teach him a lesson.” My father was livid and confronted him about this extreme behavior in response to such a minor infraction.

I had tolerated being treated in this way.

“Now that you’re an adult, can you see why he did this to you?” Marisa asked. In my mind another Brule surfaced:

I immediately saw how these three childhood models of reality were holding me back in numerous ways. My beliefs that it was dangerous to stand out, that being a good teacher meant not having wealth, and that I’d hurt or disappoint others if I asked for more, all were undermining me. I had never even realized I held those beliefs. When the beliefs were removed, massive changes occurred in my life.

What happened in the months afterward was incredible. Because my belief about standing out disappeared, I started speaking more. Almost immediately I got two major speaking engagements and my biggest speaking payment yet. I got on camera more and hired my first PR firm. It seemed as if requests for interviews and appearances came out of nowhere. I made the cover of three magazines, was more active on social media, and saw massive rises in the number of followers I had on Facebook.

I also decided I wouldn’t be a suffering teacher anymore. I gave myself the first raise I’d had in five years.

The result? In just four months, I doubled my income. My business began to grow, too. We hit new revenue milestones. It turned out that not only had my beliefs held me back but they had also been holding back my business and everyone who worked for me. These experiences proved to me how erasing old models of reality can have a profound impact on our lives.

LESSON 3: When you replace disempowering models of reality with empowering ones, tremendous changes can occur in your life at a very rapid pace.

Most of us have our own versions of disempowering beliefs. Beliefs about the way we look, about our relationship with money, about our self-worth. These beliefs can come from unexpected sources: a bullying teacher, overhearing a conversation between parents or other authority figures, or the attention (or lack thereof) from people we’re attracted to.

As we believe these things to be true, they become true. All of us view the world through our own lens, colored by the experiences, meanings, and beliefs we’ve accumulated over the years.

It’s as if we have a meaning-making machine in our minds that kicks in and creates Brules about every experience we have. So, the kids tease me and call me names. This means I must be ugly. Never mind the fact that a more likely explanation is that those kids were simply being kids, and children sometimes make fun of others. But as a kid I wasn’t mature enough to understand this, so instead I installed the model of reality that I was unattractive.

The meaning-making machine never sleeps. It runs during childhood and in adulthood, too: while on a date, dealing with your mate and your kids, interacting with your boss, trying to close a business deal, getting a raise (or not), and much more.

We add meanings to every situation we see and then carry these meanings around as simplistic and often distorted and dangerous models of reality about our world. We then act as if these models are laws. The experiences I’ve just described proved it to me personally, but scientists are beginning to study this phenomenon, and the results are astonishing. While the bad news is that our models of reality can cause stress, sadness, loneliness, and worry, the good news is that we can upgrade them. When we swap in optimized models that work better, we dramatically improve our lives.

Here are just a few of the amazing studies that speak to the power of our beliefs.

A simple suggestion can change what we think about ourselves and even our bodies, inside and out. In their report in Psychological Science on the famous study of the hotel maids, the researchers noted that just by being “told that the work they do (cleaning hotel rooms) is good exercise and satisfies the Surgeon General’s recommendations for an active lifestyle,” the women “perceived themselves to be getting significantly more exercise than before” and “showed a decrease in weight, blood pressure, body fat, waist-to-hip ratio, and body mass index” compared to those who weren’t told this.

Weirder still, in a 1994 study, ten men with knee pain agreed to take part in a surgical procedure to relieve them of their pain. They were going to go through arthroscopic surgery—or so they thought. In reality, not all ten were going to actually receive the full surgery—instead, they were part of an intriguing experiment. J. Bruce Moseley, MD, was about to test an idea that the placebo effect so common with simple pills might actually extend to more serious conditions including those that required surgery. The men were going to be fully prepped for surgery, and they were going to leave the hospital with crutches and pain pills. But Dr. Moseley performed the full surgery on only two. On three others, he performed only one part of the procedure. On the knees of the remaining five, he made just three incisions so the patients would have the sight and sensation of incisions and then scars, but he performed no actual surgery. Even Dr. Moseley didn’t know which procedure each patient would receive until just before he performed the surgery, so that he would not unconsciously tip off the patients in any way. When all ten men left the hospital, all of them believed that they might have had the surgery to alleviate their condition.

Six months later, none of the men knew who had gotten the full surgery and who had gotten the sham. Yet all ten said their pain was greatly reduced.

Imagine that! Marked improvement from a serious medical ailment for which surgery is performed—yet no surgery was performed.

The placebo effect, as it’s generally known, can be so powerful that all modern drugs have to be tested against a placebo before they are released to the public. According to Wired magazine, “half of all drugs that fail in late-stage trials drop out of the pipeline due to their inability to beat” placebos. Dr. Moseley’s work rocked the medical establishment by showing that the placebo effect could apply to ailments for which they were performing surgery. Our beliefs about our bodies seem to have an uncanny impact on how we experience our bodies—for good or bad.

If our beliefs can influence our bodies to such a dramatic degree, what else can they do? Can our beliefs influence the people around us?

The landmark studies by Robert Rosenthal, PhD, on the expectation effect prove just how much our lives are affected by other people’s models of reality, however true or false they might be. After discovering that even lab rats navigated mazes better or worse depending on the expectations of the researchers doing the training (the researchers were basically told that they had either smarter or dumber rats, when in fact all the rats were, well, just rats), Dr. Rosenthal took the inquiry into the classroom. First, he administered an IQ test to the students. Then teachers were told that five particular students had extra-high scores and were likely to outperform the others. In fact, the kids were randomly selected. But guess what? While the IQ of all of the kids had increased over the school year, those five had much better scores. The now-famous findings, published in 1968, were called the Pygmalion Effect, after the myth about Pygmalion, who fell in love with his sculpture of a gorgeous woman who came alive—much as the teachers’ expectations of those five students became reality.

Dr. Rosenthal and his colleagues spent the next thirty years verifying the effect and learning how it happens. It has also been found in business settings, the courtroom, and nursing homes. Bottom line: Your beliefs can influence both you and the people around you. What you expect, you get.

We create models of reality about the behaviors of our spouses, lovers, bosses, employees, children—but as the research shows, our beliefs influence how others respond to us. How much of the irritating or negative characteristics you see in others is really a belief you’re projecting onto them?

This brings us to Law 4.

Extraordinary minds have models of reality that empower them to feel good about themselves and powerful in shifting the world to match the visions in their minds.

Each disempowering model of reality we have is really nothing more than a Brule we’ve set up for ourselves—and, like any Brule, it should be questioned.

The monk in the hot tub helped me see past a Brule that I had to keep proving myself to validate my own self-worth. Mary’s kiss shattered my Brule that I was unattractive to women. My session with Marisa shattered my Brules that only those who suffer make good teachers and that my visibility and success could hurt me or others.

What’s the primary source of these Brules?

It’s got to do with how we were raised as children.

In Chapter 2, I quoted historian Yuval Noah Harari, PhD, who compared children to molten glass when they’re born. Kids are incredibly malleable, taking a huge number of beliefs onboard as they grow up and make meaning of the world around them. Under the age of nine, we’re particularly susceptible to making false meanings and then clinging to them as disempowering models of reality.

While we work to clear our own limiting models, it’s crucial to also make sure that we’re not saddling our children with models that are disempowering. Incidentally, the ideas below can be applied to interacting with adults, too. Remember, our meaning-making machine never turns off—it doesn’t stop just because we aren’t kids anymore. There are always opportunities to help others develop new beliefs and get rid of old, destructive ones.

Author Shelly Lefkoe and her late husband, Morty—who passed away just as I was writing this book—developed an incredible understanding of how beliefs influence our lives. I once asked Shelly, “What’s the single biggest piece of advice you could give a parent?”

Shelly said this: “No matter what you do, in any situation with your child, ask yourself, What beliefs is my child going to take away from this encounter? Will your child walk away thinking: I just made a mistake and I learned something great or I’m insignificant?”

There are many opportunities to practice this wise advice.

Suppose you’re at the dinner table with your kids and your son drops his fork on the floor. You might say, “Billy, don’t do that.” Now he throws his spoon on the ground. You say, “Billy, I TOLD YOU not to do that. You need to go stand in the corner for ten minutes and think about what you’ve done.”

Now, you might believe this is an okay way to handle things. You were calm. You simply sent Billy to a corner. But we’re losing the chance to influence the beliefs Billy might be developing from what’s happened. Remember to ask yourself: What are the beliefs my child is going to take away from this encounter?

Maybe Billy dropped his fork by accident, so when you reprimand him, he’s confused: Why doesn’t Mom trust me?

He drops the spoon to validate that belief, and sure enough, Mom gets angry and puts him in a corner. Now he forms a new belief: Mom doesn’t trust me, and I bother her. In the corner, Billy forms yet another belief: I am not worthy and I don’t have a right to speak my mind.

See how the meaning-making machine amps up?

Shelly’s advice is, at the end of any situation like that, ask your child, “Billy, what happened? What was the consequence? What can you learn from this?”

Shelly makes it very clear. Don’t ask Billy, “Why did you do that?” Why questions corner a child and put the child on the defensive. For one thing, the child is emotional, and even many adults can’t answer why in the grip of emotion. For another, it’s not appropriate to expect a young child to be psychologically savvy enough to dive into his own mind and accurately answer why he did what he did.

Instead, ask what questions: “Billy, what happened that made you drop that spoon?” This allows him to look within and think. He might answer, “I dropped it because I thought you weren’t listening to me.” What questions allow you to get to the root of the problem and work to heal it faster.

Shelly notes that why has to do with meaning, and meaning is always made up—a mental construct from the world of relative truth. Even if Billy did know why he dropped the spoon, it wouldn’t be empowering. Getting to the bottom of the situation itself—figuring out the what—allows you to work with your child to do something about it. Bottom line, Shelly suggests that when you walk away from an interaction with your child, ask yourself: What did my child just conclude about that interaction? Did your child walk away thinking: I’m a winner or I’m a loser? I made a mistake and learned something new or I’m an idiot?

Now, even if you’re not a parent, the idea here is quite profound. Imagine all the dangerous beliefs you may have taken on about the world even when the people around you were well-meaning, not to mention what happened when people’s intentions weren’t always the best.

Realizing just how much we absorb as children has made me extra careful about what I say to my kids. Over time I developed this simple hack to help remove negative beliefs in my children before they fester too long.

Every evening after work, I try to spend some time with my son, Hayden. We call this Dad and Hayden time. After playing with Legos or reading books, I tuck Hayden into bed. As I do so, I ask him two simple questions that I hope will end his day with positivity. First, I ask him to think of one thing he was grateful for that day. It could be the soft sheets he’s sleeping on, a friend he played with, a conversation we had, or a book he read. I show him that he can be grateful for anything. Second, I ask, “Hayden, what did you love about yourself today?” I ask him to talk about something he did. Maybe it was an act of kindness—he helped another kid at school. Or a demonstration of intelligence—something he figured out or something smart that he said. Maybe it was being helpful—the way he took care of his baby sister. If he can’t think of anything, then I tell him something I love about him. As we play before bedtime, I try to notice little things about him. As I tuck him in, I tell him what I saw. Last week it was, “I love the questions you ask about science. I think you have a great mind for solving problems.” If you can do this for your children, you end up raising children who are far more resistant to Brules, because inside, they are a lot more secure.

Instilling this habit into Hayden’s life is my way of trying to keep his models of reality clear of Brules before they form—but it’s never too late to start. I encourage you to integrate these exercises into your own evening routine so that you, too, will have a way of rooting out any damaging models of reality before they take hold. These two exercises work just as well for adults as they do for kids. Try it on your kids—or yourself—each night before going to bed.

Take a few minutes and think of three to five things you’re grateful for today:

Perhaps it’s how the sun felt on your face when you left the house this morning.

Perhaps it’s how the sun felt on your face when you left the house this morning.

Or the music you listened to on your way to work.

Or the music you listened to on your way to work.

Was it the smile and thank you that you exchanged with a store clerk?

Was it the smile and thank you that you exchanged with a store clerk?

Or a laugh you shared with some people at work?

Or a laugh you shared with some people at work?

Maybe it was that special look your partner, best friend, child, or pet gave you.

Maybe it was that special look your partner, best friend, child, or pet gave you.

Or the good workout tips you got from the trainer at the gym.

Or the good workout tips you got from the trainer at the gym.

Or was it just how great it feels to get home, kick off your shoes, and call it a day?

Or was it just how great it feels to get home, kick off your shoes, and call it a day?

Think about a quality or an action of yours that made you proud today. Maybe nobody else told you that they appreciated it, but it’s time that you affirmed it for yourself. Think about what it is about you as a human being that you can love. Is it your unique style? Did you solve a complex problem at work? Is it your way with animals? Your dance moves? Your jump shot? That awesome meal you cooked last night? The fact that you know the lyrics to every Disney song since The Little Mermaid? You can identify qualities that are big or small, but you must pinpoint three to five things every day that make you proud to be who you are.

You can practice this simple self-affirmation in the morning when waking up or just before going to sleep. For me, it’s helped me heal much of what the monk in the hot tub pointed out to me.

Marisa Peer suggests that all of us have a child within who never received all the love and appreciation we deserved. We can’t go back and fix the past. But we can take responsibility to heal ourselves now by giving ourselves the love and appreciation we once craved. You can help heal your own inner child.

Thus far we’ve looked at internal models of reality, models that apply to how we perceive ourselves. But external models of reality are just as powerful in our lives. Your external models of reality are the beliefs you have about the world around you.

Below are four of the most powerful new models I’ve decided to believe are true about the world.

I came to accept these four models as I went through life. They replaced older, less evolved models and added immense value to my life. Read with an open mind.

This model of reality replaced an earlier model that all “knowing” comes purely from hard facts and data. Today I strongly believe in intuition and use it in my daily life. It helps me make better decisions, know whom to hire, and even helps me with creative pursuits like writing this book. Remember how my phone sales career took off when I used intuition as part of my selling strategy? Human beings can function as logical beings and as intuitive beings. When we use both capabilities, we’re priming ourselves for extraordinary results.

Science is finding that we operate on two levels. One is what we might call instinct, which runs below rational awareness. It’s connected with prehistoric brain areas and is lightning fast. The other is the rational side that evolved later, but on which we rely heavily in our lives today.

In one study, scientists gave participants two decks of cards and told them they were going to play a card game for money. Unbeknownst to the players, both decks were stacked: one like a roller-coaster ride—major wins, major losses; the other a smoother ride—few losses, small wins. After drawing fifty cards or so, players suspected one deck promised a smoother ride. By eighty cards or so, they had the whole ruse figured out. But here’s the thing: Their sweat glands knew something was up after just ten cards. Yup, these glands on the players’ palms opened up a little with every reach toward the roller-coaster deck. Not only that, but at about the same time, the players began reaching more often for the smoother-ride deck without even realizing it! Their intuitive selves recognized and somehow drew them to the safer choice.

I believe human intuition is real, and with practice we can get better at tuning into it for decision making. I do not believe you can foretell the future, but I do believe in gut instinct in decision making. I try to listen to my gut on a daily basis. See what happens when you try to do the same.

Earlier I talked about the terrible acne I had as a teenager. With little social life to speak of, I spent a lot of time reading. One thing I read about was creative visualization. Creative visualization is a practice of shifting beliefs by meditating and then visualizing your life as you want it to evolve. It’s based on the idea that the subconscious mind cannot differentiate between a real and imagined experience. So I started visualizing my skin getting better. I spent just five minutes, three times a day visualizing my skin undergoing healing. I used imagery that felt powerful to me: looking at the sky, reaching out and scooping up some of that radiant blueness, and smoothing it on my face. I saw the blue hardening and then saw it being pulled off, taking the dead skin with it, leaving glowing new skin beneath. Essentially this process trains the subconscious mind to develop a new belief—in my case, my skin is becoming beautiful.

In one month of practicing this technique three times a day for five minutes per session, I ended my acne problem. Mind-body healing involves the conscious practice of certain mindfulness or visualization techniques to heal certain aspects of yourself. I’d had acne for five years and seen many doctors, to little avail. Using creative visualization, I healed my skin in four weeks—giving myself a huge boost of confidence and self-worth.

For those of you who’d like to try this practice, I’ve recorded a video explaining how I worked with creative visualization. I also explain the exact method I used to heal my skin. You can download it as part of the free resources on www.mindvalley.com/extraordinary.

Most of us are told to work hard. Few of us are encouraged to work happy. In the developed world, we spend close to 70 percent of our waking hours at work—but according to multiple studies, close to 50 percent of us dislike our jobs. That’s an unfortunate situation for billions of people today. Unless we’re passionate about some aspect of our work, a big part of life will feel unsatisfying.

Work, I believe, should be something that inspires you to jump out of bed each morning. From the start at Mindvalley, we embraced the idea that “happiness is the new productivity.” Our unique work culture is designed to ensure that while employees get things done, we have immense fun doing it. We do this through various models and systems designed to boost happiness. These include investing in beautiful, inspiring office design, offering flexible working hours, hosting annual team retreats to paradise islands if we hit our goals, and almost weekly social gatherings and parties to foster friendship and connection.

This culture of happiness at work significantly helps reduce the immense stress of racing to build a fast-growing company. It’s helped me keep my sanity while working long hours to hit our goals. It’s possible to bring a culture of happiness to any work environment. Whether you’re a CEO or a freelancer, an assistant or a manager, it is critically important that you find a way to enjoy your work. Have lunch with someone from your office or someone in your business network once a month, even once a week. Pay someone a compliment about his or her work every day. Or take Richard Branson’s advice. He said: “I have always believed that the benefits of letting your staff have the occasional blast at an after-hours get-together is a hugely important ingredient in the mix that makes for a family atmosphere and a fun-loving, free-spirited corporate culture. It also goes a long way to tearing down any semblance of hierarchy when you’ve seen the CFO doing the limbo with a bottle of beer in her hand.”

In short, happiness and work need to go hand in hand.

Want to learn more about my models for bringing happiness to work? I’ve given several detailed talks on my methods for injecting happiness at work to fuel a company’s productivity. You can watch a short TEDx talk or a longer 90-minute training session with information on how to apply these models to your company or business. Both are available on www.mindvalley.com/extraordinary.

The traditional model of reality goes like this: I can only be spiritual if I follow a particular religion. But why not consider that our spiritual self exists apart from religious systems, and that morality is not dependent on religion or belief in God?

Goodness, kindness, and the Golden Rule do not just have to be taught via religion. According to the book Good without God by Greg M. Epstein, the humanist chaplain at Harvard University, the fourth biggest life adherence in the world today after Christianity, Islam, and Hinduism is now humanism. Humanism is the idea that we do not need religion in order to be good. It differs from atheism in the sense that humanists believe that there is a “God,” but He’s certainly not the judgmental, angry being that many religious texts make Him out to be. Instead, to a humanist, “God” might be the universe, or the connectedness of life on Earth, or spirit. Humanism is opening up a new spiritual path for people who want to reject the Brules of religion but who don’t embrace atheism. One billion humanists now exist on the planet, and their numbers are growing.

In addition to exploring humanism, you could also try to craft your own religion—rich in tradition and self-discovered experiences, but free of the Brules of organized religion. In the book A Religion of One’s Own by Thomas Moore, the author suggests that we should all create our own religion. He writes:

This new kind of religion asks that you move away from being a follower to being a creator. I foresee a new kind of spiritual creativity, in which we no longer decide whether to believe in a given creed and follow a certain tradition blindly. Now we allow ourselves a healthy and even pious skepticism. Most important, we no longer feel pressure to choose one tradition over another but rather are able to appreciate many routes to spiritual richness. This new religion is a blend of individual inspiration and inspiring tradition.

Personally, I struggled when I left religion. I believed in a higher power, so pure atheism did not feel right to me. Then I started exploring models such as humanism and pantheism and found my answer. Today I combine ideas from humanism, pantheism, and spiritual practices like meditation with my family’s own beliefs from Hinduism and Christianity, which I pick and choose depending on how empowering these models feel.

Below is a list of the Twelve Areas of Balance from the previous chapter. On your computer or in your journal, write down the models of reality that you have in each of these categories. I’ve listed a few common ones to get you started. You should notice a correlation with your results from rating these categories in Chapter 3; in other words, the categories where you assigned the lowest rating may also have the most disempowering models of reality.

1.YOUR LOVE RELATIONSHIP. How do you define love? What do you expect from a love relationship, both to receive and to give? Do you believe love brings hurt? Do you believe love can endure? Do you believe you have the capacity to love greatly? Do you believe you deserve to be loved and treasured?

2.YOUR FRIENDSHIPS. How do you define friendship? Do you believe that friendships can be long lasting? Do you believe your friends take more from you than they give? Do you believe making friends is easy or hard?

3.YOUR ADVENTURES. What’s your idea of an adventure? Is it about travel? Physical activity? Art and culture? Urban or rural sights and sounds? Seeing how people live in places totally different from yours? Are you making time and space for adventure in your life? Do you believe you need to save for retirement before taking a long trip? Would you feel guilty if you left your job or your family to take a holiday by yourself? Do you think that spending money on experiences (such as skydiving) is frivolous?

4.YOUR ENVIRONMENT. Where do you feel happiest? Are you content with where and how you live? How do you define “home”? What aspects of your environment are most important to you (colors, sounds, type of furniture, proximity to nature or culture, neatness, level of convenience/luxury items, etc.)? Do you believe you deserve a gorgeous home, to stay in five-star hotels when you travel, and to work in great environments?

5.YOUR HEALTH AND FITNESS. How do you define physical health? How do you define healthy eating? Do you believe you’re genetically inclined toward obesity or any other health issues? Do you believe you’ll live as long as or longer than your parents? Do you believe you’re aging well or poorly?

6.YOUR INTELLECTUAL LIFE. How much are you learning? How much are you growing? How much control do you have over your mind and your daily thoughts? Do you believe you have adequate intelligence to accomplish your goals?

7.YOUR SKILLS. What do you consider something you’re “good” at? And what not so much? Where did those perceptions come from? What holds you back from learning new things? Are there some skills you’re ready to let go of? What keeps you from making the change? What special abilities and character traits do you have that you feel are most valuable? What do you feel you “suck” at?

8.YOUR SPIRITUAL LIFE. What type of spiritual values do you believe in? How do you practice them and how often? Is spirituality a social or individual experience for you? Are you stuck in models of culture and religion that hold little appeal but that you’re afraid to abandon for fear of hurting others?

9.YOUR CAREER. What is your definition of work? How do you define a career? How much do you enjoy your career? Do you feel you’re being noticed and appreciated in your career? Do you feel you have what it takes to succeed?

10.YOUR CREATIVE LIFE. Do you believe that you are creative? Is there a creative person you admire? What do you admire about him or her? What creative pursuits do you engage in? Do you believe you have a talent for a specific creative project?

11.YOUR FAMILY LIFE. What do you believe is your main role as a life partner? How about as a son or daughter? Is your family life satisfying to you? What were your values about family growing up? Do you believe a family is a burden or an asset to your happiness?

12.YOUR COMMUNITY LIFE. Do you share the values of the communities that you’re a part of? What do you believe is the highest purpose of a community? Do you believe you’re able to contribute? Do you feel like contributing?

After doing the exercise above, you should have some idea of the models of reality you need to upgrade. You don’t need to meet with monks in hot tubs or get hypnotherapy to upgrade your models. (Though wouldn’t it be nice if we could all get an instant upgrade with a kiss?) Bad models can evaporate through sudden realizations—sometimes spontaneous ones (such as I had in the hot tub)—or through meditation, inspirational reading, or other mindfulness practices, including just sitting in a room by yourself, reflecting on your life, and asking yourself, Where did I come up with this particular world view?

As you progress through this book, you’ll gain insights and experience “ah-hahs” that will open you up for letting go of certain disempowering models. There will also be specific exercises that will help you shed models through the awakening these exercises will bring. For now, though, here are two instant techniques you can apply to remove negative models of reality that you might develop on a day-to-day basis. Both are based on the idea of activating your rational mind before you unconsciously adopt a model.

While some things in the world are absolute truths (they hold true for all human beings across every culture—such as the idea that parents must take care of their children when children can’t take care of themselves, or that we all need to eat in order to survive), many things are only relative truth: They’re done differently by different cultures, such as particular ways of parenting, eating, spiritual expression, handling a love relationship, and much more.

Is your model of reality absolute truth or relative truth? If you have a model that isn’t scientifically validated, feel free to challenge it. This is certainly true of religious beliefs. One reason why as a kid I questioned my culture’s rules on eating beef was that I noticed that millions of people all around the world could enjoy eating beef. Why couldn’t I?

Is there an aspect of your culture you know is relative truth for the greater part of humanity? If you still enjoy believing it, do so. But if it’s harmful or results in your having to dress in a certain way, marry in a certain way, or restrict your diet or life in a way you dislike, you owe it to yourself to abandon it. Brules are made to be broken.

Remember that no single culture or religion dominates the majority of the planet today. No major religion holds sway over the majority of the human population. Know that whatever your culture trained you to believe, the vast majority of human beings probably do not believe. And you can choose to disbelieve, too. The power to choose what we want to believe and what we want to disbelieve is one of the greatest gifts we can give ourselves.

The best advice is often to listen to your heart and intuition. Remember that our models of reality all have expiration dates. Even what we take to be absolute truth today may not always be a truth in the future. This question is wonderful for situations where our models are indoctrinated through our culture and society. But it’s important to understand that we ourselves also create models of reality via our meaning-making machine. That’s where Question 2 comes in.

Morty and Shelly Lefkoe have an interesting model for hacking beliefs that has to do with turning off your mind’s meaning-making machine. According to Morty, we can manufacture as many as 500 different “meanings” a week. But as we learn to ask ourselves, Is this really true? Am I 100 percent sure that this is what’s really going on?—we start to reduce the number of meanings.

Morty says it’s easy to get from 500 to 200 a week if you just do an internal inventory at regular intervals to check whether you’re creating meaning where none should exist. Then it’s just about practice. Eventually you stop adding meaning to events. You will become less reactive to stress and less upset with others in your life. It helps your marriage, and I can tell you it will help your relationships with your boss and coworkers. As a CEO leading a team of 200 people, I’ve consistently found that those who had their meaning-making machines under control at work were more effective leaders.

I recorded a longer conversation with Morty on his Lefkoe belief process. This video is very personal to me as it was the last training Morty Lefkoe ever gave before he passed away in November 2015. I feel it is my duty to share his final words of wisdom with you. You can watch the full experience at www.mindvalley.com/extraordinary.

I believe the best thing we can do with outdated models of reality is to let them go gracefully. Turn them into history. Let’s celebrate our extraordinary ability to evolve emotionally, mentally, spiritually throughout life, taking on new ideas, thoughts, philosophies, and ways of being and living. When enough people challenge the Brules and adopt optimal models, you have evolutionary progress of the human race. And when enough people optimize their models all at the same time, you have revolutionary change that acts like a slingshot to hurl us to a new order, powered by the impetus of our collective awakening.

True brilliance is not a function of understanding one’s view of the world and finding order, logic, and spirituality in it. True brilliance is understanding that your view of order, logic, and spirituality is what created your world and therefore being forever capable of changing everything.

—MIKE DOOLEY

Now that you’ve taken a closer look at how models of reality take root and identified some of the key models of reality in your life, it’s time to connect those insights with the next step in consciousness engineering. In the next chapter, you’ll discover how your everyday life—your systems for living—dovetails with your models and learn how to optimize your systems to set the stage for extraordinary growth in all areas of your life.