Ivar Tengbom and the Swedish Match Company Headquarters

Ivar Tengbom (1878–1968)

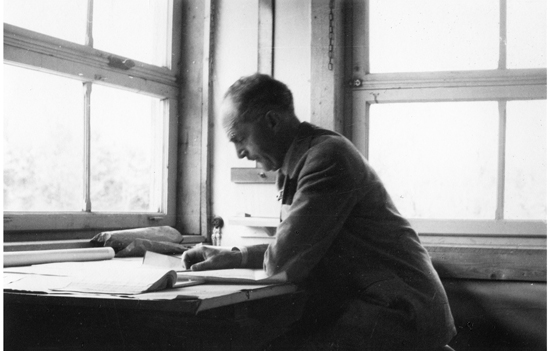

Ivar Tengbom was an architectural rarity, managing to achieve commercial success while also making a significant contribution to the development of Scandinavian architecture in one brilliant career. He was the outstanding architectural student of his year, who founded what became Sweden’s largest architectural practice and who went on to win many of the most important public commissions of the 1920s in Sweden (Figure 11).

FIGURE 11 Ivar Tengbom, Credit – ARKDES.

Born into a relatively wealthy middle-class family in Vireda in Sweden in 1878, Ivar Justus Tengbom was raised in a small country manor house as the only son of an army officer. His technical education began at the Chalmers School of Technology in Gothenburg, where he studied between 1894 and1898 before proceeding to the Architecture School of the Royal Swedish Academy of Arts in Stockholm, from where he graduated in 1901. He was the outstanding student of this period at the school and was awarded the prestigious Royal Medal on completion of his studies. The medal brought him not only the honour of having graduated top in his year but also a very generous travel grant which he used to the full – spending almost a year in Paris at the École des Beaux-Arts (the spiritual home of European Classicism)1 before moving on to the, then inevitable, tour of Italy in 1905.2

On his return to Sweden in 1906, he went to work in a rather unusual partnership with Ernest Torulf (1872–1936) who already had a well-established architectural practice in Gothenburg. Tengbom established a branch of the practice in Stockholm, and it was in this arrangement that he worked for the next five years. During this period (and despite his lengthy Italian travels), he gave every appearance of being a committed National Romantic, developing an intense interest in the vernacular architecture of Sweden, travelling extensively, measuring, sketching and photographing traditional buildings throughout the country whenever his work allowed. In the office, he worked almost exclusively on the practice’s competition entries, and following a string of second places (including second place to Ragnar Östberg (1866–1945) in the competition for Stockholm City Hall 1912–1924), they finally won the competitions for both the City Court in Borås (1909) and the Arvika Church (1908–1911), almost simultaneously. While both the church and the courts buildings are clearly in National Romantic style, there is a formality about the great symmetrical white gable of the church with its double entrance doors and central rose window, and the twin towers and decorated Classical doorway of the courthouse, which suggest a move away from the medieval and asymmetrical towards something purer and more rigorous.

On completion of the church and the courthouse (no doubt boosted by these competition wins, which he had authored, and their subsequent positive reviews on completion), he split with Torulf in 1912 and opened his own office. Within its first year, his fledgling practice secured two major commissions, the Högalid Church (1912–1923) and, via an invited competition, the new headquarters building for the Enskilda Bank (1912–1915) on an extremely prominent site adjacent to the Kungsträdgården Park in the very centre of the city. These were extraordinary commissions for a relatively young architect, and his designs for both buildings proved to be dramatic statements of the architectural intent of his new practice (particularly given his largely National Romantic portfolio up until this point).

Tengbom’s winning proposal for the Enskilda Bank was a Classical Roman palazzo, transferred to the streets of Stockholm (Fig 3). From its heavily rusticated base (complete with windows guarded by latticework steel cages), it rises through a lighter rendered facade to a projecting decorated cornice below an attic floor and mansard roof, which in turn is punctuated by semicircular attic windows. Its central entrance is marked by four sets of engaged columns above which are sculpted grey granite Norse figures of almost a storey in height by Carl Milles, which contrast with the plain upper rendered facade behind them. This is a beautifully proportioned design, whose pale grey rendered upper storeys give it a new lightness and freshness, which is accentuated by the contrast with the traditional, rusticated dark grey granite base. Throughout, the detailing is sharp and meticulous and, along with its lavish interior, which is organized around a central top-lit banking hall, this was a hugely self-confident and successful start to Tengbom’s independent career. Compared to the contemporary National Romantic work of Ernest Torulf, his old partner; Aron Johansson (1860–1936), whose correct neoclassical revival extension to the Old Parliament House had recently been completed; or indeed Ragnar Östberg’s City Hall, across the city, on which construction had just commenced, the Enskilda Bank Headquarters suggested a bold new direction for Swedish architecture and confirmed that Nordic Classicism had arrived in Stockholm. Contemporary critics drew comparisons with the Deutsch Werkbund, but Tengbom’s building looked to Italy and the Swedish vernacular, rather than Germany for its inspiration.

By all accounts, the young Tengbom was a charming, socially confident man about town, who quickly established his credibility and position within Stockholm society, in particular, developing a number of fruitful friendships amongst the city’s wealthy, artistic Jewish community. Through his reputation for a new style of Classical architecture and his increasing prominence, he became established as ‘a deluxe architect – the man to whom one inevitably came for work of the most expensive sort’.3

In 1914, he was commissioned to design a villa on one of the much sought-after plots in Diplomatstaden in Stockholm. This was an exclusive development of large detached villas, directly overlooking the Djurgårdsbrunnsviken inlet. His client was Ernst Trygger (1857–1943) who in 1914 was a supreme court judge (and who would later go on to become Swedish prime minister). The Villa Tryggerska (1914) occupied one of the typical Diplomatstaden plots, which were generally long, narrow and irregular with entry from the north and views of the Djurgårdsbrunnsviken inlet to the south. Tengbom’s design was a graceful two-storey, L-shaped brick villa below a steeply pitched, black glazed tile roof from which half-round dormers projected (as at the Enskilda Bank Headquarters). The entrance from the north was via an arched arcade overlooking a small courtyard from which the doors led to a large entrance hall, serving the public rooms. The main block facing the water is at right angles to this entrance wing with the most important rooms facing south, thus enjoying both the sun and the view of the lake. It has all the grace, refinement and exquisite detailing of the Enskilda building with brick rustication to the lower floors and a shallow stone portico to the main salon, which overlooks the garden and the lake.

Tengbom’s headquarters for the Enskilda Bank had not only established his professional reputation but had also enabled him to build a relationship with Knut Agathon Wallenberg (1853–1938), its CEO. Wallenburg was one of the wealthiest and most influential people in Sweden at the time, who, as well as running his family’s bank, was also both Swedish Minister for Foreign Affairs from 1914–1917 and a leading member of the city council in which role he was then personally overseeing the construction of Östberg’s City Hall. As a result of their professional relationship, Wallenburg went on to commission Tengbom on numerous occasions over the next twenty years both on behalf of the bank and later for the Stockholm School of Economics of whom he was a founder and major funder.

Tengbom therefore went on to undertake a series of further commissions for the Enskilda bank. He completed his first modest bank branch in Götgatan on Södermalm in Stockholm in 1916. This was a three-storey building on a potentially awkward corner site. Tengbom’s design is a simple yet subtle piece of townscape which uses an arched ground floor, which is part glazed and part open to create a covered arcade to the entrance (similar in many ways to the entrance sequence of the Villa Tryggerska). The materials are similar to the headquarters building but much more restrained with three floors of render below a steeply pitched roof with stone dressings used sparingly in quoins to the corners of the building and around the ground-floor arches.

The year 1916 also saw the completion of a branch of the bank at Borås, this time in brick with arched windows to the ground floor and square to the first floor below tall, rather beautifully proportioned, windows to the second floor again under a steeply pitched roof, which here is pierced by two tall chimneys. This is a dignified, sophisticated solution and provides a modest, yet impressive, presence for the bank and a fitting backdrop to the small square, which it dominates. Each building that Tengbom designed for the bank varied sensitively according to its location and importance – whether headquarters, major bank or branch and whether city centre, suburb or regional city – and thus consciously contributed to the new civilized, hierarchical urban order which he and the other Nordic Classical architects sought to create.

In addition to his commercial and social success, his growing professional reputation led to his appointment in 1916 as Professor of Architecture at his alma mater, the Royal Swedish College of Art, and in 1917 he was elected to the Royal Swedish Academy of Arts.

Further commissions followed including an extension to the Svenska Dagbladet newspaper offices on Karduansmakargatan (1916) and a Sanatorium in Vastergotland (1916–1918) before construction finally commenced on the new Högalid Church in Stockholm (1912–1923) in 1917. Tengbom’s design was distinguished by its grace and simplicity – a tall, simple brick nave below a steep copper roof is flanked by two elegant brick octagonal towers with the nave concluding in the simplest of pediments. The towers, which still dominate Sodermalm Island, are slightly reminiscent of Östberg’s City Hall and draw upon the same traditional Swedish Baroque source, topped with copper domes below golden weather vanes. The austere, washed grey brick interior delivers simplicity to the point of severity – as important an example of Nordic aestheticism as was produced by any architect of the Nordic Classical Movement. Finally completed in 1923, every element has the refinement and beautiful proportions, which clients and his contemporaries were now expecting from Tengbom.

In 1917, he returned to Diplomatstaden in Stockholm when requested to design a further villa, this time for District Judge Knut Tillberg (1860–1940). Again, the elongated plot led to a north-facing entrance, linking wing and south-facing main block. The entrance to this, the Bergska Villa (or Villa Tillberg (1918–1919), later renamed the Wennergrenska Palace after its next owner Axel Wennergren (1881–1961), the founder of Electrolux), was an elegant double-height bay over coupled stone Corinthian columns on either side of the recessed entrance doors. This is a much lighter affair than the earlier Villa Tryggerska with tall, shuttered windows overlooking the courtyard and lake, below a clay-tiled mansard roof. The interiors were particularly lavish with Tengbom managing to successfully combine complex wooden parquet floor patterns with deeply moulded ceilings and marble-clad columns and archways in complete contrast to the plain brick exterior.

By 1920, Tengbom was established as the most successful architect of his generation in Sweden. He was the professor of architecture, the owner of the country’s largest architectural practice and architecturally, one of the most important contributors to the development of Nordic Classicism in Scandinavia; indeed the epithet ‘Swedish Grace’4 could be applied more accurately to Tengbom’s work than that of any other architect. That year, an architectural competition was announced for the design of a new Concert Hall for Stockholm (Fig 4). The civic and national importance of the building to Stockholm and Sweden, then and now, cannot be underestimated (having been used for the annual Nobel Prize ceremony every year since its completion). Tengbom entered and was placed equal first with a design which, while clearly Classical in its roots, was executed with a new freedom, freshness and invention. The other first prizewinner was Erik Lallerstedt (1864–1955), who produced a remarkably similar design to Tengbom’s with a similarly rendered block but fronted by a colonnade with a vast rendered pediment. Tengbom was awarded the commission and instructed to proceed to detailed design and construction, and he resigned his professorship to allow himself to concentrate on the Concert Hall Commission.

Tengbom’s Concert Hall’s main elevation, facing the marketplace, is dominated by a vast, highly attenuated Classical colonnade. The giant Corinthian columns soar skywards from the simplest of square stone bases to an unadorned entablature below a stone balustrade. The entire ground floor of the colonnade is glazed, with the main body of the building behind the colonnade, in simple unbroken render from ground to roof level and most shockingly of all – this is painted bright blue – in his own words, a blue ‘like condensed air’,5 which gives this huge building a genuinely weightless quality.

In plan too, this is a Classicism freed of convention. While the main auditorium (of traditional acoustic ‘shoe box’ proportions) is bang on axis with the main portico facing the square, the route to reach it is another promenade architecturale as we twist and turn, rising through the building to the first floor, where concert-goers ‘percolate’ into the auditorium through ranges of entrances on either flank. The hall itself is a remarkable space, as described by Tengbom’s contemporary, Gunnar Asplund:

The great concert hall is midway between indoors and outdoors, but it is no compromise. It is consistently based more on musical mood than on architectural effect and, just for once, this may be right. The architecture is light and buoyant, the ceiling hovers freely, an effect, which puts one in mind of Gustavian tents on slender tent poles. The bright, inviting space and the far prospect of the orchestra platform draw one’s gaze away from the architecture and into a room which is limitless and incorporeal. This room, when filled with music, would be felt to constitute the natural framework for the most unreal of the arts.6

Glowing praise indeed from his greatest architectural competitor!

The quality of the interior of the auditorium is matched consistently throughout the building with every element from balustrades and light fittings to carpets and furniture designed by Tengbom’s office. These elements are all equally elegant in the slightly elongated proportions, which were becoming typical of his own style and of those of several other Nordic Classicists. After the bright red of the auditorium seating, the surrounding spaces are calm and painted in softer colours – lemon, aquamarine and salmon pink – with further spatial variety provided by shallow domed ceilings to reception rooms and antechambers, recessed lighting and panelling. They are probably the most sophisticated interiors of the 1920s in Scandinavia. The Concert Hall was finally inaugurated in 1926.

In 1921, Tengbom was appointed Director General of the State Office of Construction (Byggnadsstyrelsen) and in 1924, Director of Building and Urbanism to the City of Stockholm, and in 1925, his work featured largely in the Exhibition of Swedish Architecture in London, which was not only highly influential in Britain, but also established his international reputation, eventually leading to the award of the Royal Institute of British Architects Gold Medal in 1937.

By 1924, Knut Wallenberg had raised sufficient funding to provide a new building for his Stockholm School of Economics, and a site was purchased below Observatory Hill across the park from Gunnar Asplund’s City Library, which was then under construction. Tengbom was commissioned to undertake the design and produced another Italian palazzo in similar pale grey render to the Enskilda Bank Headquarters. Completed in 1926, the entrance elevation from Sveavägen is particularly restrained with the tour de force of the building being a great circular dome-topped drum, which breaks out of the rectangular mass to face the park. At ground level, this provides a fine circular auditorium and above, a four-storey circular library, which soars up past balconies to its domed ceiling, with views out to the park at every level, becoming, despite considerable competition, probably Tengbom’s most successful interior space. Externally, sadly, the treatment of the drum is weak with an excess of detail in the form of rustication, stone panels and window mullions, which greatly diminish its power. Asplund’s plain orange clerestory drum across the pond is not only stronger but also more fresh and original, making the exterior of Tengbom’s building appear rather insipid and even regressive.

By the late 1920s, the Swedish industrialist Ivar Kreuger (1880–1932) had built a manufacturing and financial empire which spanned the globe. Starting with the Swedish Match Company which was founded in 1912, he had companies listed on the New York Stock Exchange by 1925, monopolies established in numerous national markets and loans made to various national governments around the world.7 He was not only the wealthiest man in Sweden but also the third richest man in the world, and he wanted a new headquarters building as a base for his empire in his home town of Stockholm. Ivar Tengbom was his natural choice as architect, and he gave him carte blanche to design his new office. This building, which was to become known as the Matchstick Palace, was to become perhaps Tengbom’s finest Nordic Classical building and is dealt with in detail below.

And so to the early 1930s when, like so many of his contemporaries, Ivar Tengbom became more and more interested in and influenced by the emerging new Functionalist style. Asplund’s 1930 Stockholm exhibition marked a watershed for Swedish architects in particular, and after its success in promoting the new style (then referred to as ‘Funkis’ in Sweden), Classicism was, almost overnight, consigned to the past. Like many of his contemporaries (and despite the sophistication of the Classical language, which he had developed), Tengbom too embraced the new architecture and, in 1933, with apparent ease produced his first two major Functional buildings in Central Stockholm. The first was offices and printing works, The Esselte Building (1928–1932), and the second, a bank and hotel building, The City Building (or Citypalatset of 1931–1932). In both cases, all ornamentation was gone, horizontal windows were used throughout and the aesthetic of the Modern Movement had arrived in the city centre of Stockholm like the docking of two new ocean liners. While both buildings represent good examples of the new style, Tengbom had clearly struggled personally with the transition from Classicism to Functionalism. In 1931, he wrote:

Social and mass problems have become the chief interest and the cult of machinery has found fertile soil. In the midst of this age of standardization, which advances over the world like a levelling steam-roller, it ought to be worthwhile to foster the individual contribution, to leave some room for comfort and charm, if we wish to avoid mentioning such a fantastic idea as beauty. But the wind blows icy, flowers and leaves shrivel, leaving the skeleton construction of naked branches.8

This is hardly the radical manifesto of a Modernist missionary, and indeed, having produced two important early Functionalist buildings, his work slowly reverted to Classicism.

As the decade continued, there were further bank, department store and office projects, as well as several church restorations, but the expressed frames and ribbon glazing of the Esselte and Citypalaset buildings were never repeated. His offices for the State Tobacco Monopoly on Södermalm of 1933 was typical of his work from the later 1930s with a return to rendered walls, punched vertical windows and a double-height entrance doorway with stone surround – sadly with a typically Functionalist interior. In 1938, he was commissioned to design the Swedish Institute in Rome. It was almost as if the location in the ancient city of Rome inspired Tengbom to return once more to the architectural language in which he had produced his greatest work.

The building is an elegant small palazzo with a long flight of steps leading up to an outdoor, paved piazza from which a colonnade provides a subtle entrance to the building. In section and elevation, this is clearly a Palladian building, organized around piano rustica, nobile and attica under a traditional Roman clay-tiled roof. Externally and internally, he produced a series of delightful spaces – cool, elegant, beautifully detailed rooms served by fine circulation spaces and stairways and all looking out either across the ancient city or onto the sun-dappled courtyard. This was to be his last building of real architectural quality.

He continued to lead his practice and to teach through the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s almost until the time of his death in1968, veering between Classicism and Modernism, but he was now a follower rather than a leader in the development of Swedish architecture.

The Swedish Match Company’s Head Office (1925–1928)

Ivar Kreuger, Tengbom’s client for the Swedish Match Company’s new headquarters building, was the most famous and successful Swedish industrialist and financier of his generation. At the time of the headquarters commission, design and construction, his companies had a monopoly of match production in Sweden and controlled more than half the match production of the world, as well as half of the world market in iron ore and cellulose. He had bought mines all over the world, acres of land in Central Berlin and exclusive hotels and apartments in Amsterdam, Paris, Warsaw and Stockholm. He had developed an international business model which involved loans to national governments in return for a monopoly position in their national match market, eventually becoming the lender of choice to the French and German governments, valued adviser to the US President and allegedly the third richest man in the world before his empire collapsed as the Great Depression developed in the 1930s.

FIGURE 13 Tändstickspalatset Section, Credit – John Stewart.

Ivar Tengbom had worked for Kreuger previously and was the natural choice for this valuable and prestigious commission, which was to be sited in Central Stockholm just across Kungsträdgården from the Enskilda Bank. Tengbom summed up the project confidently and succinctly:

The site for this building is steeped in tradition. Once one of Stockholm’s finest residential streets, there remain today a few mansions that have been able to defy the onslaught of a new age. The street has characteristics, however, which made possible the preservation of its quality. The old houses were built to the same height as the present laws. Nor, in this case, was there any special necessity to disturb the street’s physiognomy. The task was simply to build an office, and there were no room requirements of any special kind, which could necessitate exterior peculiarities. It was the old and usual request for rooms of normal size and window space, the same requirements that had been fulfilled in this street for several centuries. The usual modern office need for large rooms with walls of glass was not present here. There was nothing to prevent the newcomer from fitting in happily in the old street.9

Tengbom’s response to what he clearly saw as the simplest of briefs was elegant, sophisticated and highly refined – understated on the street and luxurious within. Like his design for the Enskilda Bank many years previously, this is once more an urban palazzo with a central entrance marked by stylized Corinthian columns below a balcony at first-floor level, but there the similarities end, and Tengbom’s, now mature, architecture gracefully takes over.

Gone is the bold rustication, the gridded windows with their decorated entablature – the traditional division of the building into piano rustico, nobile and attica, – replaced by an elevation of what must have been of almost shocking austerity on this important city-centre street. The main elevation to Västra Trädgårdsgatan has here been stripped down to the bare essentials – lime-washed brick in lieu of stone, two rusticated wings either side of a plain central elevation, unadorned window openings with simple frames set flush with the facade – more redolent of a regional Swedish bank than a Roman palace or indeed a headquarters building where the budget was unconstrained (Figure 14).

FIGURE 14 Tändstickspalatset Entrance, Credit – John Stewart.

Unlike the Enskilda Bank, the central entrance just marks the start of the route from public to private space. The Corinthian colonnade from being merely a frame for the main doorway in the facade has here become the first row in a series of four ranks of columns which support the building above and create a dark hypostyle portico, which leads from Västra Trädgårdsgatan to the light of a courtyard beyond. These elegant columns, like the main facade, have been reduced to their bare essentials with simplified acanthus-leaf capitals, plain shafts and no base; this is Classical architecture but with a new restraint and simplicity, and Swedish architecture but without a hint of medievalism (Figure 15).

FIGURE 15 Tändstickspalatset Portico, Credit – John Stewart.

This forest of columns offers a view of a clearing beyond where a deer and a wild boar flank symmetrical staircases rising right and left. The courtyard is cut out of the solid mass of the building – a giant and unusual horseshoe-shaped space – filled with light both from the sky above and also reflected from the stunning white marble of the walls and the sparkling water of the fountain in the centre of the space.

After the unexpected restraint of the street elevation and entrance, the contrasting opulence of this urban oasis comes as a dramatic surprise. Here the lime-washed brick of the street elevation is replaced with marble from Kolmården and the ground-floor windows, here with their carved marble surrounds, alternate with blank marble panels, while below our feet – an inlaid mosaic of Prometheus – the giver of fire – appears for the first time. The balcony over the entrance is repeated once more, but now below a richly carved coat of arms, and the whole space is focused on a life-size sculpture of Diana by Carl Milles (1875–1955), raised high above the central fountain. This is the expression of power, wealth and urban sophistication, which we had originally expected of the building – made all the more powerful and impressive by having our expectations lowered en route (Figure 16).

FIGURE 16 Tändstickspalatset Courtyard, Credit – John Stewart.

The influence of Kampmann’s Copenhagen Police Station (completed in 1926, the year Tengbom started work on this commission) is clear – both in the restraint of the exterior and in the richness of the courtyard, which is here also carved out of the mass of a city block, but also Cyrillus Johansson’s (1884–1959) design for the Warehouse for AB Vin and Spritcenter in Stockholm of 1920–1923 (now a hotel), which introduced the horseshoe courtyard, as well as Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598–1680) and Carlo Fontana’s (1638–1714) Palazzo Montecitorio in Rome (1623–1696), but beyond the strategic level, the similarities end. Like the best Nordic Classicism, this is no copy or collage – the confidence and sophistication of every aspect of Tengbom’s design shows a mature and original hand at work.

In many ways this is the simplest of compositions – the horseshoe courtyard with colonnade at ground level and balustrade as cornice – but it is raised to another level by the elegance of the proportions and the quality of the details and craftsmanship. Throughout the building the skills demonstrated are outstanding – Carl Milles’s stone carving including the famous Diana fountain in the courtyard, Carl Malmsten’s (1888–1972) furniture, Simon Gate’s (1883–1945) lighting fittings and metalwork, including the beautiful courtyard gates and balcony with their forest motifs. Tengbom himself gave them full credit: ‘Without their help the result would have been a soulless construction.’10 Perhaps Tengbom is a little excessive in his gratitude.

A symmetrical pair of external stairs lead up from the entrance colonnade to the first-floor corridor (a la Copenhagen Police Headquarters), which follows the curve of the courtyard to circular lobbies, off which further stairs and the lift are reached. To either side of the courtyard are a top-lit reception hall and office with the extraordinary central curved boardroom (or Session Hall, as it was originally known) on axis looking back down on the courtyard below (Figure 17). Indoors, there is no hint of any budgetary constraint on Tengbom or his team of designers and artists. After the forest references of the courtyard, fire and stars become recurrent symbols; door handles as stylized flames and the company’s star logo is used in almost every space in parquet floors, door handles, panelling and ceiling lamps; specially commissioned clocks showing the time around the world across Kreuger’s empire, were installed throughout the building; and a revolving globe which was side-lit to show night and day and a glazed bronze lift which whisked visitors up to the double-height boardroom, where murals of Prometheus bringing fire to the dark world, by Isaac Grünewald (1889–1946), decorate the walls.

FIGURE 17 Tändstickspalatset Boardroom, Credit – John Stewart.

This was undoubtedly the headquarters building to which Ivar Kreuger had aspired in hiring Ivar Tengbom as his architect. It was (like much great architecture before it) a suitable expression of his wealth and power. For Tengbom, such was his maturity that neither the budget, the client nor their expectations overwhelmed him. The Classical primitivism of the street facade and entrance, as a precursor to the extravagance of the courtyard and the interiors, is a masterstroke and shows Tengbom’s complete understanding of the potential emotional impact of his work. Despite the evidence, wherever one looks inside the building, of extraordinary expenditure, Tengbom and his fellow artists have delivered a building of the highest architectural quality that entirely merits the popular description of ‘Swedish Grace’.

Regrettably, the interiors have been sublet and subdivided over the years, but all the principal external and internal spaces remain and further restoration is ongoing.

Much more unfortunately, its setting and views have been all but destroyed by subsequent commercial development, which was allowed on the opposite side of Västra Trädgårdsgatan, where the original garden lay, between the street and Kungsträdgården. This has completely transformed Tändstickspalatset from a sunlit commercial palazzo overlooking Kungsträdgården (above which it would have proudly been seen) to a much less remarkable composition, reached from a dark, narrow street, and for admirers of Tengbom’s architecture, the view from his last great building across the park to the Enskilda Bank, his first great building, has been lost.

For four short years, this was the setting for the climax and then subsequent crash of Kreuger’s global financial empire. On 14 March 1932, he was found dead in his Paris apartment, a 9-mm semi-automatic gun on the bed beside his body. While his life’s work may have lain in ruins – his fame turned to infamy – the result of his collaboration with Ivar Tengbom survives as one of Stockholm’s and Nordic Classicism’s finest buildings.